Illustrator and anthropologist Julien Posture discusses how human misunderstanding and machine learning devalue creative labour.

When we redesigned The Philanthropist Journal website in 2021, one of our goals was to feature the work of visual artists more prominently as a complement to our writing. We’ve learned a lot through these collaborations – about the illustrators, their work, and their processes, and what their talents and perspectives bring to the issues we’re writing about.

We commissioned writer and cultural commentator Gordon Bowness to profile three artists who have been a part of our work over the past four years: Julien Posture, Maïa Faddoul, and Claire Nest.

“I have a unique vantage point into the world of illustration,” Bowness says. “My boyfriend of 23 years is the award-winning illustrator Maurice Vellekoop. I’ve seen firsthand the perils and promise of this oft-misunderstood art form. After years of stagnant if not declining pay and ever-increasing threats from AI (from copyright theft to outright redundancy and loss of livelihood), illustrators deserve some extra love and attention. Commercial artists like Posture, Faddoul, and Nest are perceptive, hard-working and nimble – they have to be. It’s a delight to hear their insights and share their stories.”

“I have always drawn since I was a kid,” says queer illustrator Julien Posture, who grew up in the south of France in a rural, working-class family. “Images became an easy way to create my own little world and populate it with whatever I wanted,” he says. “It was very direct. There’s no intermediary; it’s just a pencil.”

Posture is a rare creature. He is a working illustrator and an academic studying illustrators. As such, he offers a unique perspective on the work of illustrators, how their creative labour is under threat by both human misunderstanding and machine learning.

Now 35, Posture bounces between Montreal and Cambridge, England, where he is finishing a PhD in anthropology on how people – and machines – look at and comprehend images. He hopes his research helps foster a world where the creative labour of illustrators is valued as labour. In doing so, he also hopes to increase the impact of the images he and other illustrators create. Offering insights both ethical and practical, Posture’s observations should be of interest to anyone in the philanthropic sector hoping to harness the power of visual storytelling, as well as those concerned with labour conditions in creative industries and the gig economy.

Flat, spare, witty, Posture’s illustrations have appeared in publications like The New Yorker:

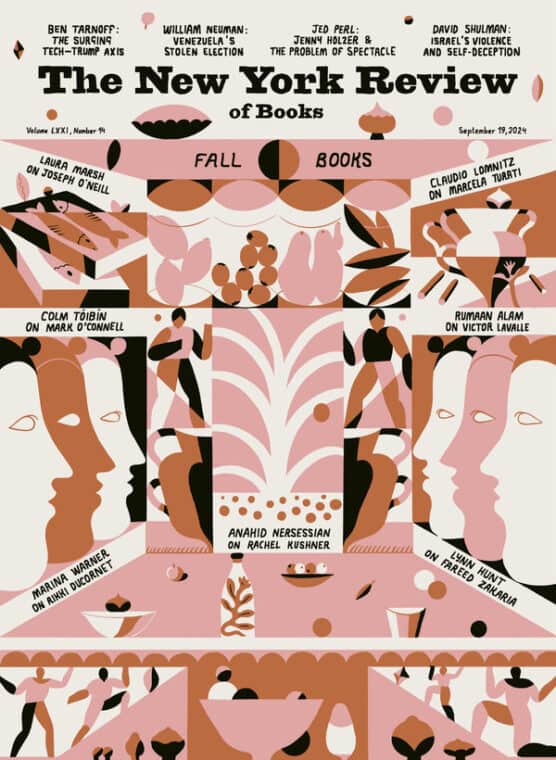

The New York Review of Books:

And The Guardian. Many have appeared in The Philanthropist Journal, too – this is the first in a series of profiles of illustrators whose work has graced this publication.

Posture is also an engaging writer who writes regularly about his research and other observations in a newsletter on Substack called On Looking and on Instagram.

In an article for It’s Nice That, the UK-based creative magazine, Posture discusses how, historically, artists have been seen to occupy an exalted realm, above such mundane concerns as making a living. “The history of art is a history of the erasure of labour,” he writes. At the same time, there is a countervailing misconception that commercial artists like illustrators are just “hands,” to use Posture’s term, automatons ready to render whatever they’re told.

These misconceptions lead to the perennial devaluation of creative work. One way to understand why is by unpacking that bugaboo of illustrators: style. Illustrators spend much of their early careers developing a signature style; it’s how they become known in the industry. The labour that goes into the development of style is rarely reflected in pay schedules. Moreover, an illustrator’s style can feel like a trap, something that limits what they have to offer. “It’s really easy to get pigeonholed,” Posture says. The pressure of making a living and satisfying clients took its toll on Posture. He gave up drawing altogether during the first year of his PhD. “I felt like my work didn’t really, quote, unquote, look like me,” he says. Then, after moving to New York City to conduct research, interviewing illustrators and art directors, Posture reconnected with his early love for making images. “I feel like having this time off renewed my sense of what I wanted to convey in my work and what I thought was important. It was a way to purge all the other voices in my head.” He’s found that doing a mix of research, writing, and illustration is more fulfilling and sustainable.

Posture’s PhD explores how an illustrator’s style is developed by a whole host of socially embedded inputs, like the point of view of clients, the needs of the market, and the upbringing and milieu of the artist.

We’re getting into semiotics here, so let’s not. Instead, let’s look at a simple Instagram post Posture made on the subject. “A style is as much about the hand that draws it as it is about the eyes that look at it,” reads a quote from Posture, rendered in blocky hand-lettering. The text sits above a drawing of a hand holding a pencil that has an eye at one end staring back at the viewer. In Posture’s analysis, style becomes a strategy, a way of navigating and reflecting society, the needs of the client, and the needs of the artist. “I see style as co-created by not only the skills of the illustrator (the hand) but also by the eyes of a myriad of other actors,” Posture writes in the post.

This rich and complex notion of style is completely at odds with the new AI tools flooding the market: text-to-image models and style-transfer models that claim to make images to order in any chosen style. “Machine-learning models, rather than being modelled on human learning or human intelligence, are really modelled on some client’s dream of what it would be like to work with an illustrator,” Posture says. “Style-transfer models are really this dream that you can just extract style from an image, whatever that means. Style for those models is completely removed from context and content of the image. So it’s kind of like this floating layer that you can peel off an image. It is supposed to be objective, but it’s just not.”

This is a capitalist fantasy, Posture argues, where creative labour is seen as one more quantifiable, predictable input. “Having style and image-making be this very standardized process with a standardized outcome,” Posture says, “fits perfectly in a very risk-averse economy where there’s no messiness, there’s nothing unforeseen. If [machine-learning models] disrupt the industry, it’s not because they reproduce something like the artist’s work; it’s because they reproduce the client’s way of seeing.”

What you’re getting with a human illustrator is not just a stylist – nor just a stylus – but a keen observer and strategic thinker. Holding that conception leads to better ways of working – like richer collaboration, an open, creative process, and proper compensation – which in turn results in imagery with greater impact.

“I never lead with the idea of a style,” Posture says. “To many illustrators, that’s the case. We lead with ideas, we lead with context, with what needs to be done.”

Julien Posture’s tips on working with illustrators and getting the most impactful images

Start early

Too often, I feel illustrators are being added at the very end of a project. So they’re being used just as hands. That’s a form of devaluation of the labour of illustrators. Whether coming up with a visual campaign, refreshing a website, or releasing an event poster, there’s a whole lot of mental and conceptual work that benefits from being included really early on in a project. [To get a better sense of how that might look, check out Posture’s post on working with The Philanthropist Journal on a story about mobilizing artists.]

Collaborate

Making images that are meaningful and culturally relevant and impactful, et cetera, has to be an iterative process, a collaborative process. There’s a lot of back and forth.

Be open

Create space to try new things and to change and explore in a way that feels authentic. Embrace the messiness. Some problems can only be resolved visually. Don’t foreclose opportunities and potentialities in an illustrator’s work.

Pay accordingly

Establish the budget range early. Keep rates aligned with inflation. Research industry standards through groups like the artist association CARFAC or the non-profit Illustration Québec.

Become more visually literate

Having someone in-house who can understand a project from the inside and be able to translate it – the brief, the input, the feedback – into something that is visually productive for an artist is completely crucial. Spend time writing strong briefs.

Beware AI

Machine-learning models are cheap, so they’re attractive to non-profits. But AI is just the first domino that falls. If you quit hiring human illustrators to do visual work, it’s not going to take long before people wonder if you stopped hiring humans to do other forms of work in your organization.

In the next instalment of this series, we profile illustrator and designer Maïa Faddoul, a case study on how social engagement informs an illustrator’s style. And we conclude the series with a profile of illustrator and animator Claire Nest, which explores further how impactful visual storytelling can be.