Summary: Since the 1960s, the field of evaluation has struggled to develop concepts and methods that are useful for the complex work of community change. The ambitious nature of the latest iteration of community change approaches, Collective Impact, amplifies this challenge. This article describes five simple rules that have emerged out of 50 years of trial and error that can assist participants, funders, and evaluators of Collective Impact initiatives to track their progress and make sense of their efforts.

Introduction

The astonishing uptake of “Collective Impact” is the result of a perfect storm. In the face of stalled progress on issues such as high school achievement, safe communities, and economic well-being, a growing number of community leaders, policy makers, funders, and everyday people have been expressing doubt that “more of the same” will ”move the needle” on these challenges. In the meantime, social innovators have been relentlessly experimenting with an impressive diversity of what we can now call “Collective Impact” prototypes and learning a great deal about what they look like, what they can and cannot do, where they struggle, and where they thrive. Many of these early efforts were described and assessed by the first rate work of the Aspen Institute, Jay Connor and the Bridgespan Group in the United States, along with the Tamarack and Caledon Institutes in Canada, to name only a few.

Then along came John Kania and Mark Kramer (FSG), who described the core ideas and practices of the first generation of Collective Impact experiments in a 2011 article for the Stanford Social Innovation Review. It was this skilfully communicated idea, presented by very credible messengers to a critical mass of hungry early adopters, that seems to have created a “tipping point” in our field and an impressive interest in this approach to addressing complex issues.

I am a participant in this “movement.” I was the coordinator of Opportunities 2000 (1996-2000), a multi-sectoral, comprehensive initiative that attempted to lower poverty levels in the Waterloo Region to the lowest in Canada. Soon after, I joined Tamarack and became the executive director of Vibrant Communities Canada (2002-2011), a pan- Canadian network of 15 coalitions focused on further developing and testing this particular approach to tackling poverty. Since branching out on my own in 2012, I have been involved in a dozen efforts to plan and evaluate Collective Impact initiatives operating in the areas of education, homelessness, and community safety.

I am aware of the many debates about Collective Impact. Is it really a new “paradigm” of community change or simply a long awaited and nicely distilled account of the work that has been going on for many years? Have many well-established organizations and networks adopted the brand of Collective Impact without really adhering to its intent, spirit, and conditions for success? Have funders embraced the approach so completely that they’ve begun to cannibalize the resources and talent required to support other productive and complementary pathways to change (e.g., direct support to local agencies, hard-edged political advocacy, etc.)? These are healthy debates and an indication of how serious people are about the challenge of community change.

What is not debatable is that people have been trying to evaluate a wide range of community change efforts for fifty years. This includes community development, coalition building, collaborative service delivery, horizontal public administration, community and regional economic development, and other comprehensive community initiatives. In the process, would-be community change makers and evaluators have learned a tremendous amount about what does and does not work in terms of monitoring, learning from, and judging the effectiveness of collective attempts to tackle complex community issues. We need to build on—not re-learn—these hard earned lessons.

In this article, I describe five simple rules that practitioners, funders, and evaluators of Collective Impact should consider in their own evaluation efforts.1 The list is not exhaustive: the art and science of learning and evaluation is too complex to be reduced to just a few points. There are also some very nice resources in development by groups such as FSG that will explore evaluation from the Collective Impact lens in more detail. Instead, these five rules are designed to surface a number of tricky issues that are a central part of any effort to plan and evaluate community change initiatives and to offer some insight into how to navigate them.

Rule #1: Use evaluation to enable – rather than limit – strategic learning

In order for evaluation to play a productive role in a Collective Impact initiative, it must be conceived and carried out in a way that enables—rather than limits—the participants to learn from their efforts and to make shifts to their strategy. This requires them to embrace three inter-related ideas about complexity, adaptive leadership, and a developmental approach to evaluation. If they do not, traditional evaluation ideas and practices will be the “tail that wags the dog” and end up weakening the work of Collective Impact.

Most Collective Impact participants are ready to accept that the vexing issues they are trying to address are complex. Unlike simple situations, where the causes of the problems are clear, the solutions well known, and the implementation of the response can be managed by one or two organizations (e.g., a vaccination campaign for meningitis), complex problems have multiple root causes, unclear solutions, and require orchestrated action by diverse stakeholders, who may not agree about the nature of the problem and how it should be addressed (e.g., gang violence), and require a great deal of learning—by-doing.2 While solutions to simple challenges have a long shelf life, the solutions can quickly become less effective as the context in which they occur evolves quickly, requiring yet another round of innovative responses in search of a more up-to-date response.

While most Collective Impact participants would agree that they are wrestling with complex problems, we often continue to operate as if we are trying to solve simple issues on steroids. We relentlessly consult with diverse stakeholders, carry out exhaustive research on the cause of the issue and the latest best practices, patiently build comprehensive strategies, and design elaborate implementation schedules. And it rarely works. The field is littered with collaborative efforts that fail to get off the ground, implode under their own weight, or simply grind to a halt because their participants are frustrated when they yield weak results.

The only way to move the needle on community issues is to embrace an adaptive approach to wrestling with complexity. This means replacing the paradigm of pre-determined solutions and “plan the work and work the plan” stewardship with a new style of leadership that encourages bold thinking, tough conversations and experimentation, planning that is iterative and dynamic, and management organized around a process of learning-by-doing. (See Exhibit 1—Edmonton’s Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness: A Case Study of Adaptability.)

Where traditional accountability models stress that social innovators should be accountable to external funders for a “high fidelity to the plan” and “delivering results on a fixed schedule,” accountability in adaptive contexts requires social innovators to be accountable to each other for achieving results over the long-term, a deep commitment to robust evaluation and learning processes, and the ability and courage to quickly change ideas, plans, and direction when the data tells them they are headed in the wrong direction or the context in which they are operating shifts so much that their approach is no longer relevant.3

The hundreds of people involved in the dozen poverty roundtables that comprised the Vibrant Communities network recognized the limitation of traditional planning and developed their own version of an adaptive approach. After we admitted that the members of local poverty roundtables were becoming tired and frustrated with trying to come up with the perfect plan for reducing poverty—and were in fact losing valuable partners in the process—we elected to focus instead on creating a “framework for change” that represented their best hypothesis or bet about how they could dramatically reduce local poverty. While the frameworks varied from community to community, they all tended to have the following elements: (a) a working definition of poverty, (b) an analysis of the leverage points for change in their community, (c) a pool of strategies to achieve, (d) a set of “stretch targets” for reducing poverty, (e) principles to guide their efforts, and (f ) a plan for evaluating their efforts.

In order to demonstrate that we were serious about our commitment to be a learning network, and that we rejected the urge to latch on to pre-determined solutions, we jokingly threatened to defund groups whose frameworks did not evolve because it indicated “they were not paying attention and not really learning.” In the end, all 13 funded collaborations in Vibrant Communities adapted (sometimes radically) their approach over their seven-to-ten-year period, including the groups that had the greatest success, such as Vibrant Saint John and the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction.

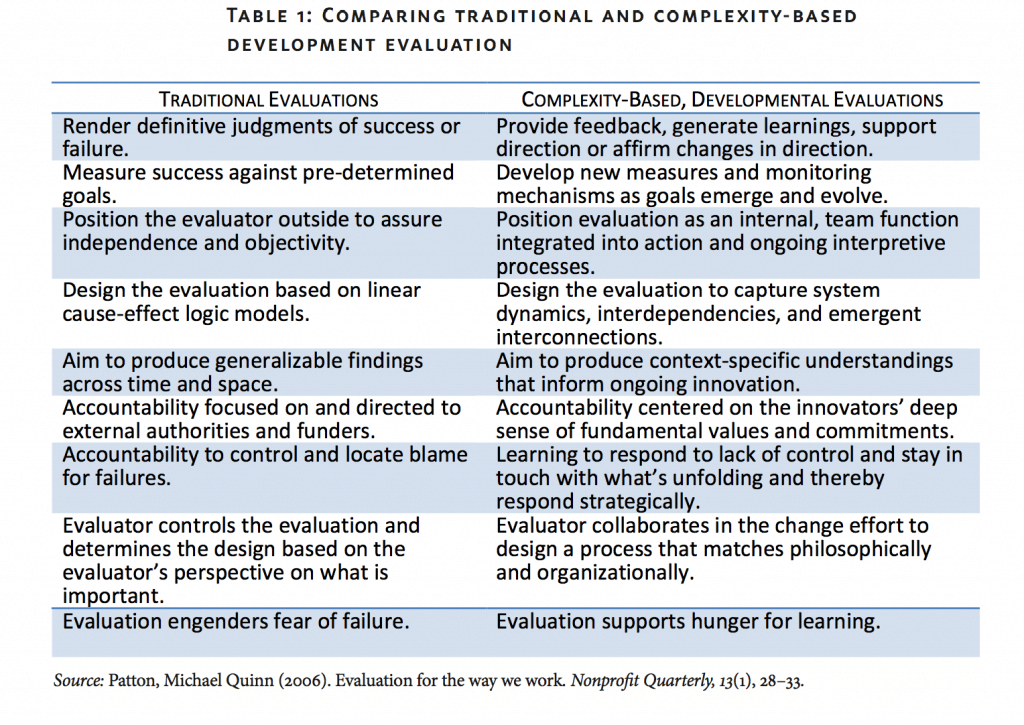

Embracing a complexity lens and adaptive approach to tackling tough community issues has significant implications for evaluating Collective Impact efforts. It means making Collective Impact partners—not external funders—the primary audience of evaluation. It requires finding ways to provide participants with real-time—as opposed to delayed and episodic—feedback on their efforts and on the shifting context so that they can determine whether their approach is roughly right or if they need to change direction. It begs participants to eschew simplistic judgements of success and failure and instead seeks to track progress towards ambitious goals, uncover new insights about the nature of the problem they seek to solve, and figure out what does and does not work in addressing it. They must give up on fixed evaluation designs for ones that are flexible enough to co-evolve with their fast-moving context and strategy. In short, they need to turn traditional evaluation upside down and employ what is called Developmental Evaluation by some and Strategic Learning by others (see Table 1).4

Table 1

For people firmly rooted in a traditional version of evaluation, this complexity-based approach might appear soft and willy-nilly. For a group that is eager to solve a tough challenge and hungry for evaluative feedback, however, it requires an even more robust and disciplined approach than typically provided by conventional assessment. Vibrant Community partners were relentless about tracking the outcomes of their efforts (some even kept weekly “outcome diaries”), freely admitted to and examined failures (we published a series of “sad stories”), invited their peers to critique their work, and held regular community-wide reflection sessions to make sense of it all and determine if they needed to update their framework for change. We could write a book about the flaws in the assessment of the Vibrant Communities initiative, but it was hardly flaky.

The environment for Developmental Evaluation and Strategic Learning is improving all the time. It’s a major theme at professional evaluation conferences all over North America, and intermediary organizations, such as the Center for Evaluation Innovation and FSG, are developing very practical resources that can be employed by Collective Impact practitioners. More philanthropic funders, like the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation in Canada and Atlantic Philanthropies in the United States, are encouraging their grantees to employ Developmental Evaluation in their work and are ready to cover the costs of doing so.

While a complexity-based approach to evaluating community change is still the exception, not the rule, it is remarkable how far the ideas and practice have come in just ten years.

Rule #2: Employ multiple designs for multiple users

With so many diverse players, so many different levels of work, and so many moving parts, it is very difficult to design a one-size-fits-all evaluation model for a Collective Impact effort. More often than not, Collective Impact efforts seem to require a score of discrete evaluation projects, each worthy of its own customized design.

Even straightforward developmental projects require a diverse and flexible evaluation strategy. For example, in a long-time partnership between a half-dozen schools, service agencies, and funders to improve the resiliency of vulnerable kids in the inner core of a major Canadian city, a series of interviews with the decision-makers in each of the participating organizations revealed that they required three broad “streams” of assessment:

• school principals and service providers wanted evaluative data in the spring to help them improve their service plans for the upcoming school year;

• the troika of funders required evaluative data to “make the case” for continued funding, with each funder requiring different types of data at different times of the year; and

• the partnership’s leadership team wanted a variety of questions answered to help them adapt the partnership to be more effective and ready the group to expand the collaboration to more schools.

In order to be useful, this Collective Impact group required what Michael Quinn

Patton, one of the world’s most influential evaluators, calls a “patch evaluation design”:

multiple (sometimes overlapping) evaluation processes employing a variety of methods (e.g., social return on investment, citizen surveys), whose results are packaged and communicated to suit diverse users who need unique data at different times. Eventually, the members of the school-service partnership elected to develop evaluation designs to feed two streams of work—annual service planning and funder data—leaving the discussion of replication issues for a future time when the opportunity and pressure for expanding the partnership was greater.

The idea of multiple evaluation consumers and designs will not be a hit with everyone. It may confuse Collective Impact participants who perceive evaluation as a mechanical process of collecting data on key shared measures of progress, frustrate evaluators who prefer neat and tidy evaluation designs, and give pause to those funders who are reluctant to pay for evaluation in the first place. However, these inconveniences are far outweighed by the benefits of crafting flexible evaluation designs that are more likely to provide Collective Impact decision-makers with the relevant, useable, and timely evaluative feedback they need to do their work properly.

Rule #3: Shared measurement if necessary, but not necessarily shared measurement

The proponents of Collective Impact place a strong emphasis on developing and using shared measurement systems to inform the work. In their first article on Collective Impact, Kania and Kramer (2011) make the following bold statement:

Developing a shared measurement system is essential to collective impact. Agreement on a common agenda is illusory without agreement on the ways success will be measured and reported. Collecting data and measuring results consistently on a short list of indicators at the community level and across all participating organizations not only ensures that all efforts remain aligned, it also enables the participants to hold each other accountable and learn from each other’s successes and failures.

I could not agree more. In fact, I will add another reason that shared measurement is important for collective action. The process of settling on key outcomes and measures can sharpen a Collective Impact group’s thinking about what they are trying to accomplish. The case for robust measurement processes in Collective Impact efforts is overwhelming.

Luckily, we know a lot about the models and mechanics of shared measurement. Mark Friedmann’s resources on Results-Based Accountability detail very practical ways for individual organizations to develop indicators, which work at both the programmatic and community wide level. The Aspen Institute has summarized the lessons of using Performance Monitoring in Comprehensive Community Initiatives, while FSG has stepped up its efforts to track, distil, and share the latest developments in the field. The stage is set for the practice of shared measurement to lurch forward.5

While the case for shared measurement is strong and the practice increasingly robust, it’s important for Collective Impact participants to proceed with caution in this area. Specifically, there are at least five things to keep in mind while crafting a common data infrastructure:

1. Shared measurement is critical but not essential. The key players in the community-wide effort in Tillamook County in Oregon to reduce teen pregnancy admit that they had “significant measurement problems,” but this did not prevent them from reducing teen pregnancy in the region by 75% in ten years. This is not a reason to ignore shared measurement—it simply illustrates that the lack of a system is not always crippling to a Collective Impact group.

2. Shared measurement can limit strategic thinking. Many veterans in the field of poverty reduction argue that employer wages and the benefit levels in government income support programs can have a far greater impact on poverty than innovations in front line social services, where the case for aligning measures across organizations may be quite strong. By pre-determining the indicators to be measured, the group is inherently limiting the scope of their observations. Collective Impact participants should focus on strategies with the highest opportunities for impact, not ones that offer greater prospects for shared measurement.

3. Shared measurement requires “systems change.” In order to solve the “downstream problem” of fragmented measurement activities, local Collective Impact groups need to go “upstream” to work with the policy makers and funders who create that fragmentation in the first place. Policy makers and funders often work in silos to develop “categorical” policies and programs, highly targeted for discrete groups and for specific purposes, and with very specific measurement requirements. Local leaders interested in shared measurement are then left with the responsibility—but not with the power, authority and resources—for weaving this all together in a coherent package. This is silly. In order for shared measurement to work, policy makers and funders and local leaders must work together to align their measurement expectations and processes.6

4. Shared measurement is time consuming and expensive. While it is true that innovations in web-based technology have dramatically reduced the cost of operating shared measurement systems, it can still take a long time and a surprisingly large investment to develop, maintain, and adapt such systems. The Roberts Enterprise Development Fund in the San Francisco region, for example, spent millions of dollars over a ten-year period to develop, test, and refine a relatively discrete set of measures to track the effects of the youth training programs of their grantees. Collective Impact participants should carry out a rigorous assessment of the costs of developing and maintaining such a system so that they enter into the work with their eyes wide open.

5. Shared measurement can get in the way of action. A talented and hardworking network of Collective Impact participants in the greater Toronto area have elected to keep their strategy “in first gear,” while they sort out their outcomes and measures, and have been spinning their wheels for years trying to land on the right ones. Collective Impact initiatives should avoid trying to design large and perfect measurement systems up front, opting instead for “simple and roughly right” versions that drive—not distract—from strategic thinking and action.

All in all, it is important that we not oversell the benefits, underestimate the costs, or ignore the perverse consequences of creating shared measurement systems. When developed and used carefully, they can be important ingredients to a community’s efforts to move the needle on a complex issue. Poorly managed, they can simply get in the way.

Rule #4: Seek out intended and unintended outcomes

All Collective Impact activities generate anticipated and unanticipated outcomes, and participants and evaluators need to try to capture both kinds of effects if they are serious about creating innovation and moving the needle on complex issues.

This is easier said than done. The effects of even the simplest initiatives are hard to predict. An experiment by health activists to improve local access to fresh vegetables through rooftop gardening in a Chicago neighbourhood resulted in less-than-anticipated health benefits for vulnerable families, but unexpectedly led to the widespread adoption of the practice because landlords discovered that the gardens improved the insulation of older apartment buildings and tenants enjoyed getting to know each other while tending the gardens.7 A program designed to help women on social assistance start up micro-enterprises, improve their financial literacy, and expand their savings led to tension and even abuse in marital relationships because partners didn’t appreciate the women’s newfound independence. Unanticipated outcomes can be good, bad, or somewhere in-between.

The number and variety of splatter effects dramatically increases in comprehensive community change efforts, which typically have multiple interlocking interventions. For example, a comprehensive region-wide initiative to reduce the production and accessibility of crystal meth in the American mid-west resulted in the actors in the drug trade developing newer, more-difficult-to-monitor ingredients, re-locating their manufacturing activities to nearby counties, and establishing more resilient, tougher-to-locate, and violent distribution networks. Talk about innovation! This is a classic example of the “fixes that fail” archetype often encountered when navigating complex systems, and every Collective Impact effort is rife with potential pitfalls.

It is critical that the participants and evaluators of Collective Impact efforts understand and capture all of the ripple effects of their activities. This (a) provides a more holistic view of what is—or is not—being achieved, (b) offers deeper insight into the nature of the problem that they are trying to address and the context in which they are operating, (c) triggers groups to adjust or drop strategies that may not be delivering what they had hoped, and (d) surfaces new, often unexpected, opportunities as they emerge. Without a complete picture of their results, the chances that Collective Impact participants will be successful are dramatically reduced and the likelihood of unintentionally doing harm to a community or group is substantially greater.

Unfortunately, conventional evaluation thinking and methods have multiple blind spots when it comes to complex change efforts.8 Logic models encourage strategists to focus too narrowly on the hoped-for results of a strategy, ignoring the diverse ripple effects. Limited evaluation budgets pressure administrators to focus scarce resources on tracking difficult-to-measure progress towards goals and targets. Outcomes dashboards tend to highlight only the results that can inform “results-based accountability” and aggregate data may mask underlying trends. Together, these traditional practices create a dysfunctional type of evaluation tunnel vision.

Happily, it is possible for Collective Impact participants and evaluators to adopt a wideangle lens on outcomes. It begins with asking better questions: rather than ask “Did we achieve what we set out to achieve?”, Collective Impact participants and their evaluators should ask, “What have been ALL the effects of our activities? Which of these did we seek and which are unanticipated? What is working (and not), for whom and why? What does this mean for our strategy?” Simply framing outcomes in a broader way will encourage people to cast a wider net in capturing the effects of their efforts.

There are a variety of practical ways to answer these questions. Some of these include: (a) asking participants to brainstorm all the possible outcomes in advance of a strategy so that they are sensitized to the possibility of unanticipated ones and can look for them as they implement their strategies; (b) not telling external evaluators about the hopedfor outcomes so that their research is free from bias; (c) retaining some of the evaluation budget so that it can be used to further investigate unanticipated outcomes when they emerge; and (d) employing first-rate techniques designed to spot and investigate the inevitable surprises of development work (e.g., most significant change, outcome harvesting). We appear to be at the start of a small-scale methodological renaissance in this respect.

In the end, however, the greatest difficultly in capturing unanticipated outcomes lies more in the reluctance of Collective Impact participants to seek them out than in the limitations of methodology or the skills of evaluators. Many Collective Impact participants are so conditioned by results-based-accountability and management-by-objectives that they can’t see the “forest of results” because their eyes are focused on “the few choice trees” that they planted. Others are fully aware of the messy effects of their work but are unprepared to deal with the complications that might arise when they put them on the table. As a colleague in a Collective Impact initiative admitted to me recently, “We can barely deal with the frustration of not getting the results we want. I don’t think we can handle the idea that there are other results—good or bad—that we should be paying attention to.”

When a great French General asked his gardener to plant an oak tree, his gardener replied that there was no rush because it took oak trees a hundred years to mature. The General responded, “In that case, there is no time to lose; we need to plant the seed this afternoon!”

It may well take a very long time to create a culture where people are deeply curious about all the effects of their work, so let’s push for having unanticipated outcomes as part of any Collective Impact conversation wherever and whenever we can and see how far we can get.

Rule #5: Seek out contribution – not attribution – to community changes

One of the most difficult challenges for the evaluators of any intervention—a project, a strategy, a policy—is to determine the extent to which the changes that emerge in a community are attributable to the activities of the would-be change makers or to some other non-intervention factors.

A story from the popular book, Freakonomics, illustrates the point nicely. When the rate of violent crime across the United States dropped dramatically from 1974 to 1989, there were many organizations eager to claim that it was their efforts that were responsible for the shift. Common explanations included tighter gun laws, more community policing, and tougher sentencing. While there are studies that demonstrate that each of these efforts improved community safety in some way, a broader and more rigorous analysis revealed that the majority of the improvement was most likely due to (a) a variety of large scale demographic shifts—some of which were due to shifts in public policy—which led to a drop in the number of vulnerable young men (the greatest perpetrators of violent crime) and (b) changes in the drug market that reduced the profit margin on some drugs (e.g., crack cocaine) to such a degree that drug distributors were no longer willing to “go to war” to protect or expand their share of illegal markets.9

The question of attribution is a major dilemma for participants and evaluators of Collective Impact initiatives. Collective Impact participants need to sort out the “real value” of their change efforts and the implications for their strategy and actions, yet determining attribution is the most difficult challenge in an evaluation of any kind.

The traditional methodology for assessing attribution is a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). This involves establishing two (ideally) randomly selected groups—an experimental one that is the subject of a discrete intervention and a control group that does not experience any intervention (or receives a placebo intervention)—and tracking the difference in select indicators between the two groups over time. The hope is that this methodology can determine definitively and objectively whether any intervention (an injection or a comprehensive strategy) generates a different outcome than would otherwise occur.

The problem is that Collective Impact initiatives don’t meet the requirements for RCTs. RCTs are designed to assess relatively discrete interventions (e.g., a job search program), whereas Collective Impact initiatives tend to be sprawling efforts with multiple moving parts. RCTs require interventions to be “fixed” during the assessment, while Collective Impact strategies and activities are constantly evolving. While RCTs require a randomly selected—and statistically significant—number of subjects in the intervention group and control group, Collective Impact projects are (usually) a sample size of one. The list of incompatible requirements goes on. Gold standard RCTs might be suitable for discrete parts of a Collective Impact initiative (e.g., a pilot project or a single intervention), but they cannot be used to assess the broader effort.

This would seem to leave participants of Collective Impact initiatives with four options:

1. Commit to only developing strategies that meet the strict conditions of RCTs.

This dramatically reduces the range of strategies they can employ, essentially guaranteeing that they will not “move the needle” on community well-being.

2. Claim that whatever changes emerge in a community are largely attributable to their efforts. This is untrue, does not help Collective Impact groups determine if their activities are value-added, and eventually breeds cynicism among Collective Impact participants and their supporters.

3. Assert that it is “too difficult” to assess attribution and declare that everyone’s activities contribute to observed changes. While this is nobler than claiming 100% credit, it still does not help Collective Impact groups determine whether or not their efforts are effective.

4. Acknowledge that multiple factors are likely behind an observed change or changes and seek instead to understand the contribution of the Collective Impact effort activities to the change.

Of course, option four is the only acceptable one. The concept and methodology of contribution analysis was first laid out by John Mayne, a former employee of the Treasury Board, who felt that the federal government needed an alternative to RCT. The idea behind the approach is very simple: rather than try to definitively prove the causal relationship between intervention activities and results, program designers should simply acknowledge that the intervention is only one of many factors behind a community change and seek to assess the relative contribution of the intervention.

The six steps of contribution analysis are well developed, but evaluators must customize how they unfold to fit the unique circumstances of each intervention, which can range from simple projects to more comprehensive strategies.10 For example:

• The Caledon Institute interviewed officials in the Government of Alberta to assess the contribution of a well-organized Calgary-based advocacy network to the government’s changes to policies and benefit levels in a provincial program for people with disabilities. Officials reported that the campaign was “unexpectedly helpful” but had little influence on the substance of changes, which had been “in the works” for some time. This was a “big surprise” to the group, who assumed that their efforts were the key influencers in the policy changes. This feedback led to them to decide to begin their next campaign earlier on in the policy-making process when politicians and civil servants’ perspectives on the issues were still in development.

• The staff of the Toronto Region Immigration and Employment Council (TRIEC) asked regional employers to describe all their unique organizational efforts to recruit, hire, support, and retain skilled immigrants, and then asked those same employers to rate the contribution of TRIEC’s programs on those actions on a scale from one to seven. They were happy to learn that employers consistently provided ratings on the higher end of the scale—something they “felt but did not know”—which caused them to shift their discussion to how they might scale up their efforts to reach even more employers on the basis that their existing strategy and “mechanisms for change” were the right ones.

• A community economic development group in southern Ontario, which had developed an existing micro-enterprise development program used contribution analysis results to help them decide which direction they might take the program in its next stage: a program to reduce poverty for low income entrepreneurs, or an economic development program designed to help stimulate a lackluster local economy. When they pulled together a combination of participant feedback, Statistics Canada data, and prior research to assess the program’s impact on start—up rates and economic activity in different urban neighborhoods, they concluded that the contribution was “noticeable,” but not dramatic. This was the evidence the group needed to decide to go with the poverty reduction option.

These examples may not be dramatic, but they are instructive. In each of these cases, the simple process of (a) acknowledging that their activities may not have been the only cause of whatever results they’ve observed, (b) formally asking the contribution question, and (c) using some method to try and answer it, led to the groups making shifts in strategy that they would not likely have made otherwise. People talk endlessly about evidence-based decision-making and this is a real example of it right here.

There are other ways that contribution analysis can be useful to Collective Impact participants. Simply asking a group to consider the question can encourage them to think more critically about their work. For example, one group immediately initiated a wave of discussions that eventually led them to drop a variety of activities they admitted did not “add crazy value” to a community safety campaign. Another group, whose work required them to coordinate the efforts of diverse organizations on collaborative projects (e.g., customized training, a large social housing project), used contribution analysis as a way to share varying degrees of credit for results amongst members, much like hockey players are awarded two points for a goal and one point for an assist. Contribution analysis is a multi-purpose concept.

Despite the obvious benefits of the approach, the methodology is still not widely employed nor well developed in the field of community change. I scan the Web regularly for examples and rarely come up with much. In my own work, only one-quarter of the Collective Impact groups I have come across even express an interest in the topic. This must change. If Collective Impact stakeholders are serious about understanding the real results of their activities and using evidence—not intuition—to determine what does and does not work, they will make contribution analysis a central part of their evaluation strategy.

Conclusion

It is obvious that the field is going to be busy over the next few years working on the evaluation dimensions of Collective Impact. Evaluation is both an intrinsic component of the Collective Impact framework—enabling the rapid feedback loop that is so critical to adjusting strategies, divining innovations, and supporting the continuous communication among partners that Kania and Kramer describe as one of Collective Impact’s five key conditions—as well as ultimately providing a way to assess the overall efficacy of these complex initiatives in the longer term.

This second generation experimentation will be that much stronger if it builds on the experience and results of the first generation prototypes. I firmly believe that the five simple rules or guidelines described in this article will prove useful and need not be re-learned:

• embrace a strategic learning approach to the work,

• accept the value of multiple designs for multiple evaluation users,

• be thoughtful and cautious about shared measurement,

• assertively seek out the unanticipated effects of Collective Impact, and

• make contribution analysis a more central part of your evaluation strategy.

I look forward to the continuing conversation.

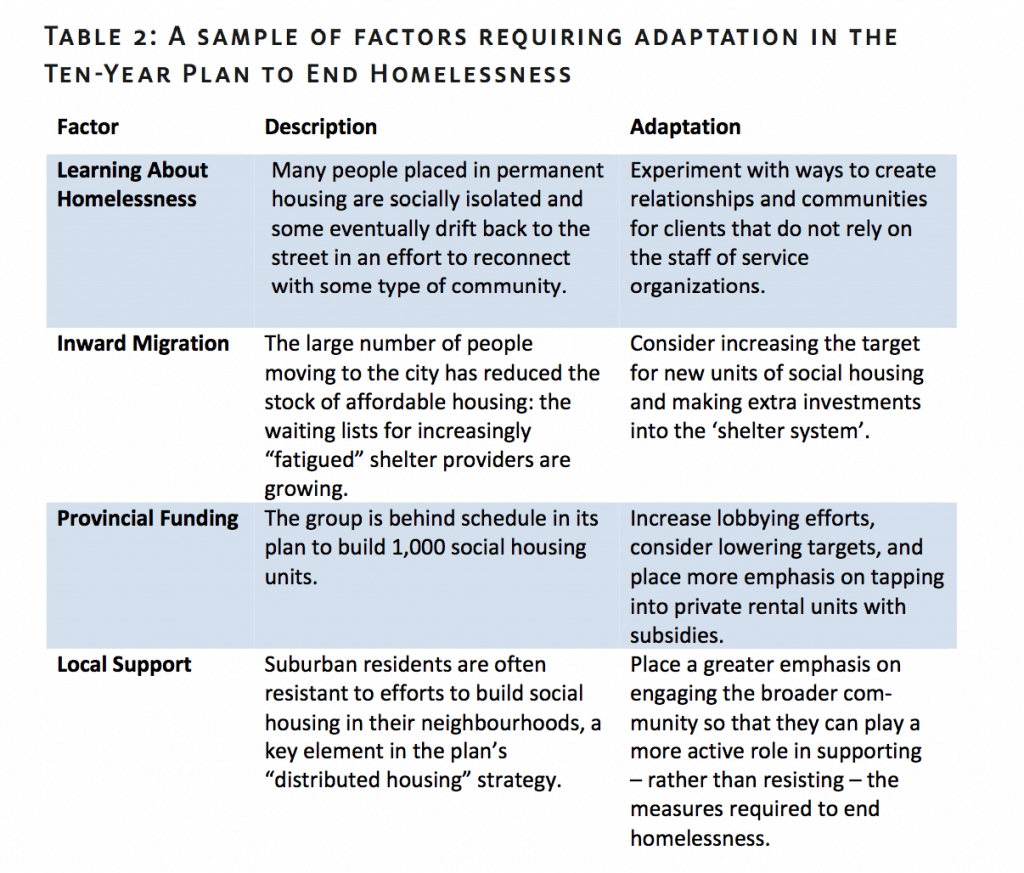

Exhibit 1: Edmonton’s Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness: A case study of adaptability

The Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness in Edmonton is a classic Collective Impact initiative and a good illustration of the nature of adaptive leadership and strategy.

The participants of this initiative organized their approach on the housing first philosophy—which emphasizes providing homeless persons with permanent housing and giving them wrap around services to deal with the issues that led to their homelessness in the first place—an approach considered a “best practice” because of the promising results of using this model in other cities. After committing to this “theory of change,” they crafted a plan with five measureable goals, each with its own targets, strategies, and timelines, and organized the financial resources, leaders, and partners required to move it forward. The Task Force had “planned the work,” and it was now the job of implementing agencies, supported by a strong backbone organization, Homeward Trust, to “work the plan.”

However, the organizations involved felt pressure to adapt the plan to respond to shifts in context, new learnings about the complex nature of homelessness, and debates about strategies and implementation amongst its diverse partners (see Table 2). This adaptability is a key contributor to the group’s remarkable success in moving the needle on homelessness: in just five years, they have built 500 new units of housing, placed over 2,400 persons in permanent homes, and reduced the aggregate number of people who are chronically homeless by nearly one-third (i.e., from 3,079 to 2,174).

Table 2

The group expects that they will need to continue to adapt their approach in the future. As the city’s Mayor admitted, “Ultimately, a lot of things have to come together for us to actually meet this goal.” This includes redoubling efforts to prevent people from becoming homeless in the first place. One prominent local service provider noted, “At one point, our success in taking people off the street is being outstripped by the increasing number of people who are now forced to call the street their home—we need to spend more time on the other end of this problem.” It might even include re-thinking the timeline for the plan. As one seasoned veteran of homeless campaigns mused, “Our plan to reduce homelessness in ten years is on track, but at this pace and with this strategy, it may take 30 years.”11

Notes

1. The idea for “simple rules” format is not new—I stole it from Tom Kelly, former Director of Evaluation for the Annie E. Casey Foundation, who used this format to describe his lessons on evaluating Comprehensive Community Change Initiatives (CCIs) in his article: “Five simple rules for evaluating comprehensive community initiatives”: http://sigknowledgehub.com/2012/09/01/introduction-to-developmental-evaluation/ .

2. This useful distinction between different types of problems was described in the article, “Leading Boldly,” by Ronald Heifetz, John Kania and Mark Kramer (2004, Winter) in Stanford Social Innovation Review, pp. 21-31, URL: http://www.ssireview.org/articles/ entry/leading_boldly [June 13, 2014]. For a more elaborate exploration of the different kinds of leadership and management styles required for simple to complex challenges, see David Snowden and Mary Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision-Making,” (2007, November), Harvard Business Review, pp. 1-8, URL: http://hbr.org/2007/11/aleaders-framework-for-decision-making/ [June 13, 2014].

3. John Kania and Mark Kramer’s article, “Embracing emergence: How collective impact addresses complexity,” in a January 2013 blog entry of the Stanford Social Innovation Review, offers a helpful lens on this approach. http://www.ssireview.org/blog/entry/ embracing_emergence_how_collective_impact_addresses_complexity [April 1, 2014].

4. For more on Developmental Evaluation, see: http://sigknowledgehub.com/2012/09/01/ introduction-to-developmental-evaluation/ . For more on Strategic Learning, see: http://www.evaluationinnovation.org/focus-areas/strategic-learning .

5. For further information on Mark Friedmann and Results-Based Accountability™, see the Fiscal Policy Studies Institute website at http://resultsaccountability.com/. For information on Performance Management in Comprehensive Community Initiatives, see the Aspen Institute’s Community Building publications at http://www.aspeninstitute.org/policy-work/community-change/publications. FSG provides information on Strategic Evaluation on their website at http://www.fsg.org/OurApproach/StrategicEvaluation.aspx and in their publication “Breakthroughs in Shared Measurement and Social Impact” available at http://www.fsg.org/tabid/191/ArticleId/87/Default.aspx .

6. There are some very good examples of policy makers and funders working with local service organizations to create shared measurement systems. The Finance Project, for example, published an account of different funding models used in the USA to support early childhood development systems and streamlined reporting requirements. In Canada, the United Way of the Alberta Capital Region has recently launched a shared reporting and measurement system with two other major funding organizations in the region.

7. See McKnight, J. (1995). The careless society: Community and its counterfeits. Basic Books: New York.

8. See Britt, H. (2013) “U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID),” Bureau for Policy, Planning and Learning. Complexity aware monitoring. URL: http:// usaidlearninglab.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/Complexity%20Aware%20Monitoring%202013-12-11%20FINAL.pdf [April 1, 2014].

9. Freakonomics: A rogue economist explores the hidden side of everything (2005) is a non-fiction book by University of Chicago economist Steven Levitt and New York Times journalist Stephen J. Dubner that argues that economics is, at root, the study of incentives.

10. For an overview of Contribution Analysis, see the article “Using theory-based approaches to make causal inferences” on the Treasury Board of Canada website at https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/cee/tbae-aeat/tbae-aeat08-eng.asp. An explanation with further commentary and references is available on the Better Evaluation website at http://betterevaluation.org/plan/approach/contribution_analysis .

11. For further information about Edmonton’s Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness, see the Homeless Commission’s website at http://homelesscommission.org/. A copy of A Place to Call Home: Edmonton’s Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness (2009) is available at http://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/documents/10-YearPlantoendHomelessness-jan26-2009.pdf , and a case study has been prepared by the Canadian Homelessness Research Network as part of their “Housing First Case Studies” series and is available at http://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/Edmonton_HFCaseStudyFinal. pdf . The quote from Mayor Don Iverson comes from a CBC News story “Edmonton plan to end homelessness hits bumps,” http://www.cbc.ca/m/touch/canada/edmonton/ story/1.2502289 [April 1, 2014].

Mark Cabaj has been involved in evaluating programs and social change initiatives since 1994.

He was an “early adopter” of developmental evaluation as Executive Director of Vibrant Communities Canada (2002–2011) and now works as an independent consultant and Associate of the Tamarack Institute.

Email: Mark@here2there.ca .