Editor’s Note:

The proposed changes in the tax treatment of charities contained in the federal Budget proposals of November 12, 1981 (Resolutions 138 and 139) drew an immediate response from The Association of Canadian Foundations.

The Association’s initial response was followed up by a brief submitted in December, 1981, analyzing the effect of the federal Budget proposals both on charitable foundations and registered charitable organizations receiving support from Canadian foundations.

The federal government has announced changes to those Budget proposals in its Release of April 21, 1982, (see page41) concerning the tax treatment of Canadian charities in response to submissions of organizations such as The Association of Canadian Foundations. It is of some interest to compare the changes to the resolutions as originally framed and as amended by the Release, discussed under Recent Tax Developments in this issue, with the submissions made by the Association. Therefore, both the initial response and the brief submitted by The Association of Canadian Foundations, together with the text of resolutions 138 and 139, are reproduced in full.

The following resolutions were put forward in the federal Budget proposals of

November 12, 1981:

Resolution 138: Registered charities

That for taxation years commencing after November 12, 1981,

(a) each gift (other than a gift described in subparagraph 149.1(12)(b)(iii) of the Act) received in the preceding year from a registered charity, other than a related charity, be included in the receipts of a registered charitable organization or public foundation for purposes of computing the amount required to be devoted to charitable activities or given to qualified donees,

(b) a registered charity in receipt of a gift (other than a gift described in subparagraph 149.1(12)(b)(iii) of the Act) from a related charity be required to expend the amount thereof in the year of receipt on charitable activities or on gifts to qualified donees,

(c) a special tax be imposed on each registered charity equal to the amount by which the amount required to be expended in the year on charitable activities or on gifts to qualified donees exceeds the amount actually expended thereon and the tax be refundable to the extent that amounts expended in the three subsequent taxation years on charitable activities or on gifts to qualified donees exceed the amounts required in those years to be so expended,

(d) for the purpose of determining the disbursement quota for a private foundation, the 5% rate be increased to 10% and be applicable to the greater of the cost amount of the property and its fair market value at the commencement of the year, and

(e) the definition in subsection 149.1(1) of the Act of a qualified investment for a private foundation be altered to exclude

(i) investments in any corporation that is controlled by or does not deal at arm’s length with the foundation,

(ii) any mortgage where the mortgagor is a proprietor, member, shareholder or settlor of the foundation or is a person with whom any such proprietor, member, shareholder or settlor does not deal at arm’s length, and

(iii) shares of a class of the capital stock of a public corporation that are not listed on a prescribed stock exchange in Canada.

Resolution 139: Income and receipts of registered charities. That where after November 12, 1981 in a taxation year,

(a) a registered charity chooses not to use or fails to use in accordance with the terms and conditions specified by the Minister of National Revenue any property or income accumulated with the Minister’s consent,

(i) the amount thereof be deemed to be a receipted donation received by it in the year, and

(ii) for the purpose only of subsection 149.1(5) of the Act, the amount thereof be deemed not to have been expended on charitable activities during the taxation years while it was being accumulated,

(b) a registered charitable foundation disposes of a capital property (other than a capital property used by the foundation in its administration or directly in charitable activity), any capital gain or capital loss on the disposition be included in computing its income for the year, and

(c) a registered charity receives any gifts from related charities and disburses any amounts to related charities, the amount of such disbursements that will be recognized as gifts by the registered charity to qualified donees be restricted to the amount by which the aggregate of all such disbursements by it in the year to related charities exceeds the aggregate of all such gifts received by it in the year from related charities.

Letters from:

The Association of Canadian Foundations Ste. 304,4881 Yonge Street, Willowdale, Ontario M2N 5X3

Telephone (416) 226-6323

The Honourable Allan MacEachen Minister of Finance Government of Canada House of Commons Ottawa, Ontario November 19, 1981

Dear Mr. Minister:

I am writing to you on behalf of the 70 members of the above Association who contribute annually upwards of $50 million to Canadian charitable organizations.Your proposal to require the foundations to include capital gains in income for disbursement purposes will cause considerable harm to the charities supported by the foundations in this country. Permit me to explain how your proposal will impact on the foundations and the charities.

Aside from those few foundations receiving bequests or other donations (generally the community foundations), a foundation’s only source of income is from its investments. Recognizing that inflation continually erodes the purchasing power of the available income and thus reduces the number of good causes and charitable works which can be supported, the majority of foundations endeavour to invest their assets in a manner which would produce a balance between continued growth in income and in the asset base. If the asset base does not increase, the income generated therefrom will increase only marginally. This in turn means the 40,000 or more operating charities, including the universities and hospitals, would receive less and less from the foundations in terms of real dollars.

Foundations today are unable to support more than 25% of the requests received from these charities. Your proposal will mean even less support in the long term. At a time of government cutbacks and fiscal restraint it is difficult to understand why you would propose legislation which would reduce even further the money available for the arts, medical research, education, social services, etc. At a time when your government should be encouraging increased philanthropy you are proposing rules which will have the opposite effect.

The eventual outcome of your proposal will result in a decrease in the number of Canadian foundations and a decrease in the effectiveness of those which do continue. If inflation continues, even the most simple mathematical projections would indicate your proposal will spell the death knell of Canadian foundations. I am sure you are aware of the support of the Canadian foundations of the universities in this country, and I want you to be well aware of the harm you will be doing these institutions as well as the other charitable organizations in Canada.

On behalf of the Canadian foundations and also on behalf of the operating charities, I urge you to reconsider this proposal and delete it from the budget.

We would be pleased to meet with you or your representative to discuss this proposal and other aspects of the proposed changes in the tax treatment of charities. Yours sincerely C.A. Bond, F.C.G.A. -Secretary December 16, 1981

Dear Mr. Minister:

Attached is our submission commenting on the budget proposals pertaining to the tax treatment of Canadian charities.

While we recognize these proposals have been put forth as a means of ensuring there will be a reasonable return to the public on the tax exempt funds of the charitable foundations, we believe the method of achieving this aim is incorrect.

The record will show that the existing distribution requirements are being met by an overwhelming majority of foundations, not only in the legal sense, but in the spirit and intent of the current legislation. In our opinion, it is wrong to introduce legislation which, while aimed at the few foundations which your department is aware of as taking advantage of the current rules, will seriously harm the future granting abilities of the majority.

We urge you to reconsider these proposals, particularly the capital gains provision and the increase to a 10% minimum payout on the non-qualified investments.

We believe a meeting with you would be conducive to developing legislation which would fulfill your aims as well as protecting the ability of Canadian foundations to continue to fulfill the distinct role for which they were created. We, therefore, request a meeting with you at your earliest convenience.

May we please hear from you soon. Yours sincerely C. A. Bond, F.C.G.A.- Secretary SUBMISSION TO THE MINISTER OF FINANCE ON THE TAX TREATMENT OF CHARITIES AS PROPOSED IN THE FEDERAL BUDGET OF NOVEMBER 12, 1981 AND SPECIFICALLY IN THE NOTICE OF WAYS AND MEANS MOTION RESOLUTIONS 138 AND 139

This brief, on behalf of the members of The Association of Canadian Foimdations is supplementary to our letter of November 19, 1981. It identifies some of the more serious effects your recent proposals will have on Canadian charitable foundations and, more importantly, the equally detrimental effect of these proposals on the many thousands of registered charitable organizations receiving support from the Canadian foundations.

Grant-making foundations in Canada constitute, we believe, a distinctive and important national resource. With assets of over $1 billion and total annual disbursements exceeding $100 million, the foundations support a wide range of social services, cultural institutions, research and other voluntary activities. Indeed, they are a vital bulwark of the voluntary sector, to the increasing importance of which the Prime Minister of Canada has recently been drawing attention. Furthermore, they have the potential of being more innovative and risk-taking in their grant-making than is frequently possible or desirable with public funds. Whatever their political views, Canadians generally share the objective of maintaining a pluralistic society and the opportunities for initiative and creativity that it affords. Any measure seriously constraining the legitimate grant-making activities of foundations militates against the maintenance of such a society and, at very least, should not be undertaken without its enormous implications being made clear to all Canadians.You state one of your reasons for the current proposals is to “ensure that existing requirements for disbursement of receipts and income are not bypassed”. This statement implies that Canadian foundations are not living up to the intent of the existing distribution requirements—an implication to which we strongly object. We believe that, although you may know of a few foundations taking undue advantage of the existing rules, it is manifestly self-evident that the majority of foundations are more than meeting both their legal and moral obligations.

Your recent proposals, particularly the capital gains provision and the increase to a minimum payout rate of 10% on non-qualified investments, while resulting in a larger distribution to charity initially, will, in the long term, result in a substantial reduction in the contributions to charity with serious and irreversible consequences.

Government fiscal restraints at all levels are making the operating charities more dependent on the private funding sector. If, in addition, the Canadian foundations through the impact of your budget proposals, become an ever-decreasing source of funds for the charities, the ultimate result will be a lessening of the services provided to the people of Canada by the operating charities.

Before commenting on the individual proposals, we must express our concern and disappointment that an opportunity was not afforded the philanthropic community to review such important proposals, which have major implications for the future of charitable foundations, prior to inclusion in the budget. In 1975, the then Minister of Finance provided, through a green paper, an opportunity for a dialogue before a decision was made to change legislation. We submit that this procedure was eminently fair and resulted in legislation which, while in some cases caused difficult adjustments for foundations and operating charities, did finally reflect an understanding of the manner in which the philanthropic community operates. Your present method of proposing change does not reflect the same understanding and indeed indicates an apparent bias against the philanthropic community; raising the important question of the government’s attitude toward the future survival of private philanthropy in this country.

We find it incomprehensible that you, members of the cabinet, members of parliament generally, or the Canadian public are intent on making the fundamental changes in our pluralistic society implicit in the current proposals.

We will now discuss and comment on Resolutions 138 and 139 of the Notice of Ways and Means Motion to amend the Income Tax Act.

Resolution 138(a)

While we support measures to prevent the movement of funds from one charity to another simply for the purpose of avoiding disbursement requirements, we recognize there will be situations where gifts from a registered charity to a public foundation will be donated, and earmarked, for the specific purpose of creating an endowment. We therefore recommend that the Income Tax Act be amended to allow a registered charity to apply in advance to the Minister of National Revenue for authority to establish an endowment fund to which such gifts might be donated and retained as capital. We recognize that the Act does make provision for accumulations, but this is for a specific purpose for a specific period of time. There should be a specific mechanism by which a charitable foundation might hold, as capital, gifts provided for that purpose by a registered charity.

Resolution 138(b)

As the term “related” charity is not yet defined, it is difficult to comment on this proposal, but we suggest that the definition of a “related” charity should not be so broad that it will seriously hamper the activities of such registered charities as hospitals and hospital foundations and colleges and college foundations.

Resolution 138(c)

While we recognize this proposal provides an alternative to deregistration of a charity not meeting the distribution requirement, the levy of a special tax, presumably payable shortly after year end, is a punitive measure. When calculating the disbursement quota of a private foundation, situations may arise where there is a disagreement between Revenue Canada and the foundation as to the fair market value of an asset. If the foundation has used a lower value than that finally determined by Revenue Canada, it could result in a deficiency in the amount expended, but this would not be known until after the taxation year in question, by which time the foundation may not have the ability to make up the deficiency. In addition, it is not clear whether, if a charitable foundation borrowed money to make up the deficiency, this action would be a cause for deregistration; furthermore, any interest expense related to such borrowing would appear not to be deductible in arriving at the income, 90% of which is distributable.

We suggest that the present averaging provisions contained in section 149.1(5) of the Income Tax Act be used to determine if a deficiency exists on which the tax is exigible. In addition, the Act should provide that the disbursements in the subsequent years, up to a maximum of three years, are applied first to recover the tax previously paid rather than the application of only the excess distributions; accordingly, in most cases such a method would result in the tax being payable in respect of the current year.

Resolution 138(d)

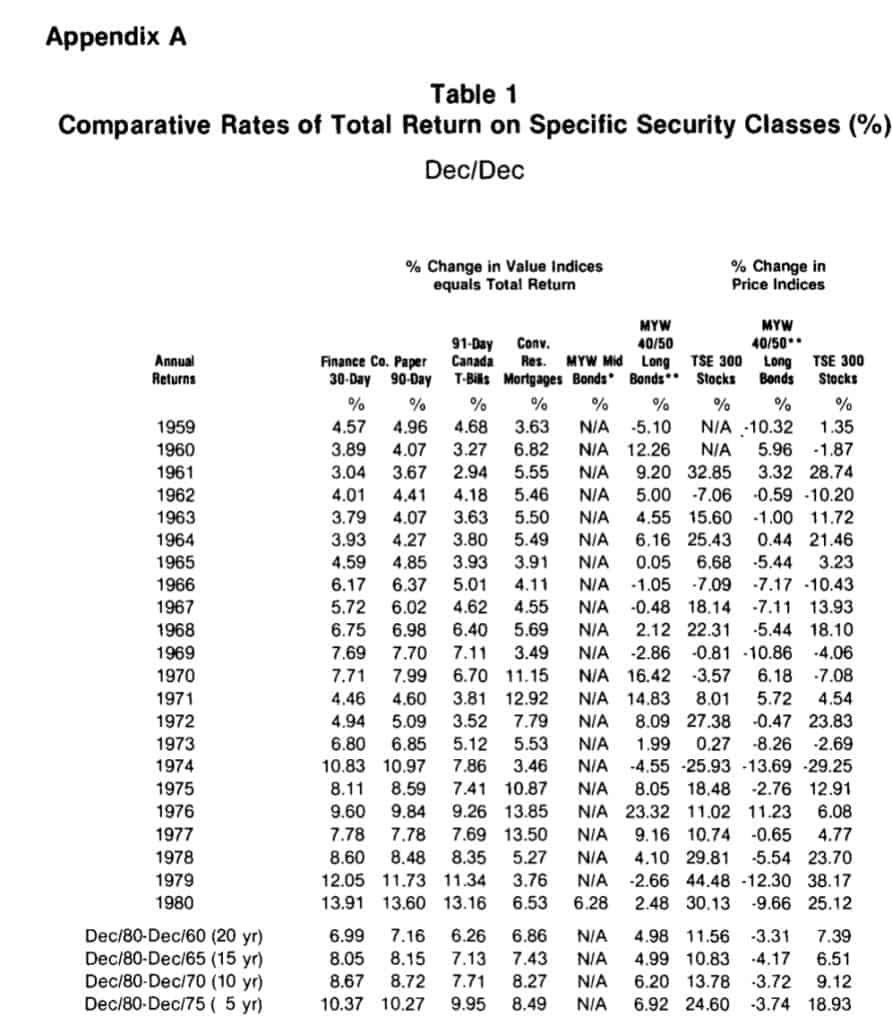

We strongly disagree with your proposal to require a private foundation to meet a minimum payout requirement of 10% on non-qualified investments. While we realize that certain years have seen an investment climate which provided total returns (income and appreciation) in excess of 10%, such yields other than on equities, have not been obtainable on a long-term basis. If capital gains and losses are removed from the yields, one would find that no class of investment has consistently returned a 10% yield. Please refer to Appendix A, (M.Y.W., Table 1)* for an illustration of the comparative total investment returns obtainable in Canada over the past 20 years.

This proposal, when coupled with the inclusion of capital gains in income for disbursement purposes, places the private foundation with non-qualified investments in double jeopardy. As the 10% minimum payout is generally unattainable over the long term, a private foundation will be required to expend capital to meet the deficiency in the minimum payout and, also, when any such

*Appendix A, McLeod, Young Weir Limited, Table l.

asset is disposed of, the private foundation will be required to include the full capital gain in income for disbursement purposes. We will comment later on the inequity of the capital gain proposal.

We strongly oppose the increase in this minimum payout and request that this proposal be deleted from the budget. We submit there is no logical or practical reason to expect a minimum payout on non-qualified investments greater than the payout required on the qualified investments.

Experience has now shown that the concept of qualified versus non-qualified investments is one which is causing difficulty to many foundations. We would welcome the opportunity to review thoroughly this provision of the Income Tax Act.

Resolution 138(e)

As indicated above, some of our members are experiencing difficulties with qualified versus non-qualified investments. We are obviously concerned about the narrowing of qualified investments. While we do not disagree with the intent of this proposal in the context of a “family situation” without any public involvement, we do not believe that the concept of a non-qualified investment should be extended where there is obviously public involvement. Accordingly, qualified investments would include shares traded in the unlisted market in Canada and shares traded on the Canadian stock exchanges where there is a sizable float in the hands of the public.

Resolution 139(a)

This proposal is a reasonable change and we do not disagree with its intent.

Resolution 139(b)

This proposal is not acceptable to the members of the Association nor, we believe, to the many thousands of charities served by the foundation community. We have a number of comments on this proposal:

1. The asset base of most foundations will decrease in terms of “real” dollars.

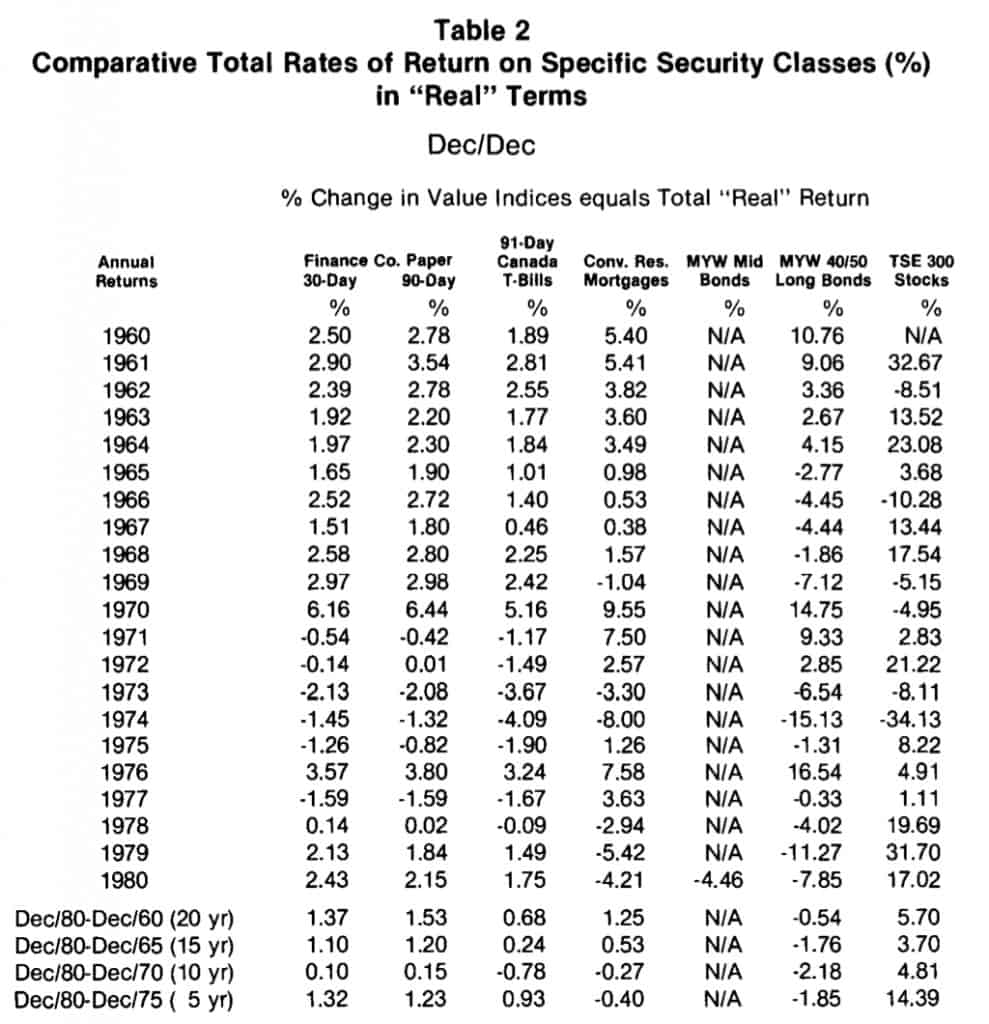

While financial data in the public information returns would indicate foundations’ assets or capital have been increasing in current dollars, the reverse is true when the impact of inflation is taken into account. Admittedly, studies of comparative total rates of return (income and appreciation) on specific security classes over the past 20 years indicate that real returns have been attainable. (Appendix A, M.Y.W., Table 2) However, the fact remains that as foundations have been dispersing to charity the majority of income each year, they have been consistently losing ground in real value.

If now, in addition, 90% of realized capital gains must be disbursed to charity, the asset base will be eroded further and more rapidly, particularly if inflation continues at the current high levels.

In actual fact, if foundations are to maintain the purchasing power of their assets, it would require not only the retention of realized capital gains but also a reduction in the existing distribution requirements from 90% to a considerably lower figure.

In support of the above assertion, we respectfully submit a copy of the results of a recent study (Appendix B, Foundation News, Sept/Oct. 1981) showing the impact of inflation on the U.S. foundations. This study indicates a decrease in real dollars in the asset values of our U.S. counterparts, even when able to retain realized capital gains.

2. The erosion of the asset base of Canadian foundations will lead to decreased charitable contributions in future years to the point where most foundations will eventually be unable to fulfill a meaningful role in philanthropy.

Referring again to U.S. studies, the attached Appendix C, excerpted from The Mott Foundation Annual Report, 1980 clearly indicates the devastating effect of inflation on the purchasing power of income distributions and asset values, assuming an average investment portfolio under differing distribution requirements. Obviously, if 90% of realized capital gains must also be disbursed, the Canadian foundation financial picture would be materially worse.

Each year both the number and dollar value of the requests by the operating charities to the foundations increases as inflation impacts on the charities’ operating costs, special projects and service programs.

If the foundations can only meet a decreasing number of these requests while at the same time government fiscal restraints are imposing cutbacks in support of the charities, the end result must inevitably be the cancellation of many needed social programs and the demise of many worthy agencies.

3. Registered Canadian charities have been recognized by successive governments as distinct from all other classes of taxpayers and should continue to be so recognized.

In permitting tax-exempt status, government has recognized the special nature of the philanthropic community as opposed to the profit-oriented sector and the individual taxpayer. Consequently, it does not logically follow that, as all other classes of taxpayers must account for realized capital gains in income, it is only fair that charitable foundations must do likewise.

Tax rules applicable to the registered charities must stand on their own and not be imposed simply because a similar rule applies to another sector of society. Even if it could be successfully argued that registered charities should, in the case of capital gains, be treated the same as other classes of taxpayers, the budget proposal does not provide equal treatment.

4. Long-term grant commitments and a planned, consistent level of granting will no longer be possible.

As foundations will no longer have the ability to increase the asset base in pace with inflation (and, in fact, as we have shown, the assets in real terms will decrease), it will not be possible to forecast accurately future “income”. This, in turn, means the foundations will not make commitments to support projects and programs beyond one or two years. The operating charities will have no assurance of long-term funding and they will be reluctant to undertake many much-needed new projects for fear of a lack of future financial support.

As realized capital gains (or losses) do not come about on a consistent basis as does the flow of dividends or interest income, the “income” of a foundation could fluctuate considerably year to year. This fluctuation will make it exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to develop any consistent level of granting, again to the detriment of the operating charities. Additionally, exceptionally large realized gains in a year could place a foundation in a position of distributing funds, not on the basis of worthy applications, but simply to meet the distribution requirement. Indeed, if a substantial net capital loss is incurred in a year, which would be applied against dividend and interest income, it could result in little or no “income” for disbursement purposes in that year. These problems and situations would undoubtedly lead to investment decisions being made on the basis of tax law rather than prudent investment policy.

5. No transitional rules have been provided for in this proposal. The lack of transitional rules is clearly unacceptable, but as we do not agree with the capital gains proposal, we will not comment further on the absence of such rules.

We believe the negative impact of this proposal far outweighs any advantages which it might have been thought would be achieved and we recommend that this proposal be deleted from the budget, and further, the existing distribution requirement be maintained.

Resolution 139(c)

We are in agreement with this proposal and support the intent of it, subject to the definition of “related” charities.

These various proposals will not only reduce the effectiveness of existing foundations, but will inhibit the establishment of new foundations. With respect Mr. Minister, we believe the impact of these proposals was not fully considered, particularly as there was no prior discussion between the charitable community and your department. We urge you to reconsider these proposals, or postpone the implementation of any changes in the tax treatment of charities to permit time for a thorough discussion between your department, the foundations and the operating charities and other segments of the public affected by these proposals.

Appendix A

* The MYW Mid-term Bond Index was developed and first published in 1980. The Index contains 40 bonds covering all major borrowing classes. The average term to maturity of bonds in the Index is approximately 6-8 years.

* * The MYW 40/50 is a combined series with an average term of 17-23 years. Up to 1976, the 40-Bond Indices were used; at January 1977, they were replaced by our Weighted

50 Indices.The data for the combined series were back-tracked to ensure a smooth transition. Historical data for the combined series and a general description of the Weighted 50 are available from Mcleod Young Weir Limited.

All Value and Price Indices except TSE 300 Price and Value Indices are Copyright© Mcleod Young Weir Limited 1981. Reproduction in whole or in part without acknowledgement of Mcleod Young Weir Limited as the source is strictly prohibited.

Rates of Return Adjusted for Inflation Over the last two or three years, we have had many requests from clients asking us to present our nominal rate-of-return data in real terms so that readers can see what the “real” rates of return would be over different time periods on the various classes of securities. As a result, we have reworked our historical data to show the inflation-adjusted real rates of total return (i.e., income plus capital gain or loss) on these investments.

Real Rates of Return in Canada 1960-1980

To arrive at measures for the real rate of return on various types of securities, we deflated all our price and value indices by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) which was used as a proxy for the rate of inflation. The deflated total return data are shown in Table 2 (set out below). The CPI was used not only because it covers the largest sector in the economy, but also because it is a consistent monthly historical series which is highly visible and closely monitored by the debt and equity markets.

All Value and Price Indices except TSE 300 Price and Value Indices are Copyright © McLeod Young Weir Limited 1981. Reproduction in whole or in part without acknowledgement of McLeod Young Weir Limited as the source is strictly prohibited.

The particular CPI series used was Cansium series 0484000, “all items”, not seasonally adjusted.

Appendix B*

Effects of Inflation On Foundation Dollars

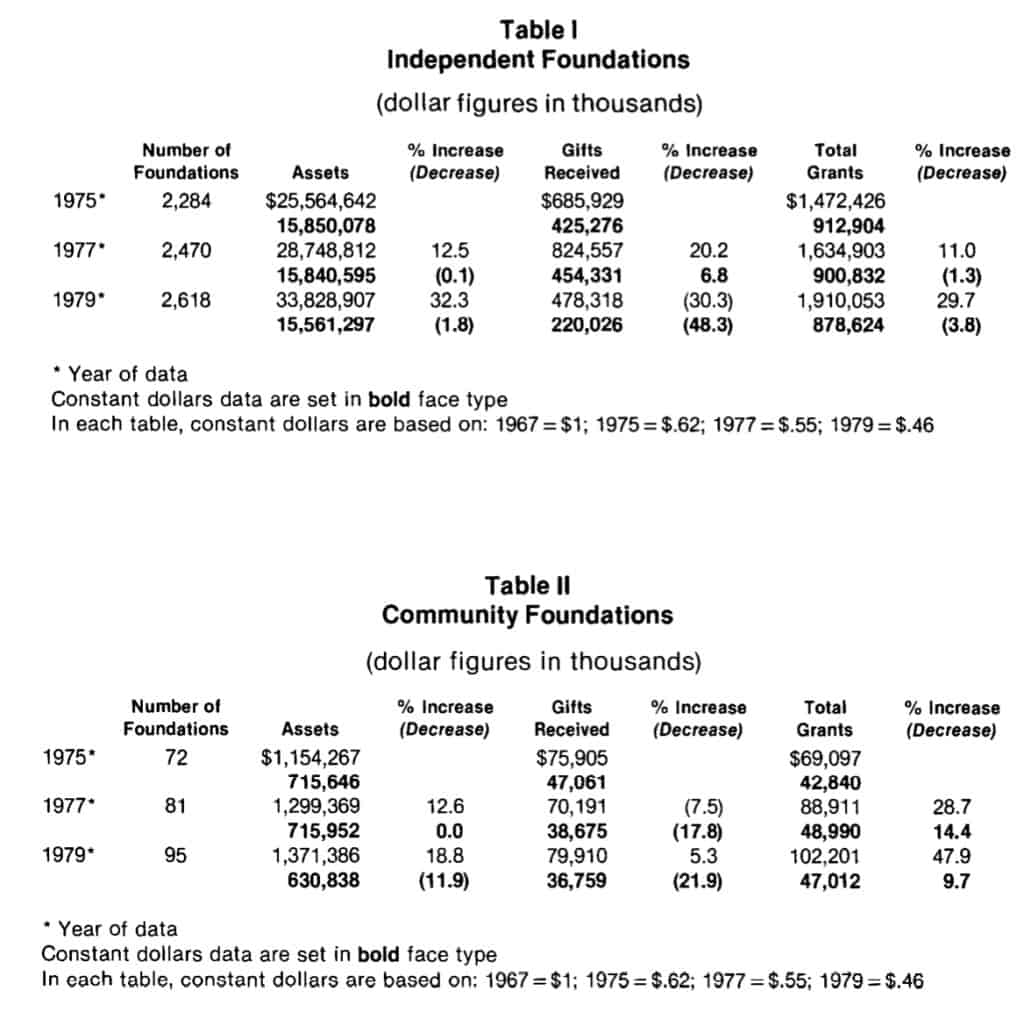

Inflation, government regulation of minimum annual payout, and limitations on the deductibility of new gifts to endowments have had a serious impact on both the short- and long-term grantmaking ability of American private foundations. Except for a dip in 1975, asset values in current dollars have increased steadily since 1965, reaching $38.4 billion by 1979. When factored for inflation, however, real assets actually grew only in the 1965-1972 period, then dropped to $16.7 billion in 1975 and have remained relatively flat since then. Although current dollar assets are projected to climb above $41 billion for 1981, a continuing decline in real asset value is expected.

The Foundation Center analyzed data for foundations having either assets of $1 million or more, or annual giving of $100,000 or more, to find out how they are faring economically at the beginning of the 80’s.

Foundations analyzed represent 15.1 per cent of all grantmaking foundations in the United States, but they hold 93 per cent ·of the assets and grant 89.1 per cent of the dollars. Of this group of 3,363 foundations the great majority are independent foundations. Taken as a group, independent foundations seem to be hardest hit—inflation making the greatest inroads, regulation creating a double bind. At the same time that inflation deteriorates the real value of assets and of grants, independent foundations cannot attract a sufficient number of new dollars for endowment to counterbalance the loss. Payout requirements may leave little opportunity for greater investment. The result is decline or, at best, stagnation. This is strikingly true of independent foundations as shown by the data for the years 1975, 1977, and 1979 in the three most recent editions of the Foundation Directory (Table 1).

In Table I, inflationary dollars have increased the number of foundations qualifying for inclusion in the Directory over the four-year period 1975-1979. Assets in current dollars have increased by 32.3 per cent, but in constant dollars (1967= $1.00) have decreased slightly by 1.8 per cent, resulting in a level endowment pool. New gifts to endowment are down 30.3 per cent in current dollars and 48.3 per cent in constant dollars over four years. This is a sharp reversal of the improvement noted in the comparison of 1975 and 1977 data.

Current grant dollars have increased nearly 30 per cent over four years, but in real value there has been nearly a four per cent decline. Thus, as the data show, the effective giving power of independent foundations has undergone a slow but steady decline in four years. There is little in general reporting on the economic trends from 1979 to 1981 that would lead us to conclude that this decline is not continuing. During the same period, those who rely on foundation giving have experienced rising costs stoked by inflation and often by a broader need for services provided. The scarcity of private money for public good when government is withdrawing much of its support leaves many nonprofit service providers in difficult circumstances.

*Foundation News, Sept./Oct. 1981, The Foundation Center, New York.

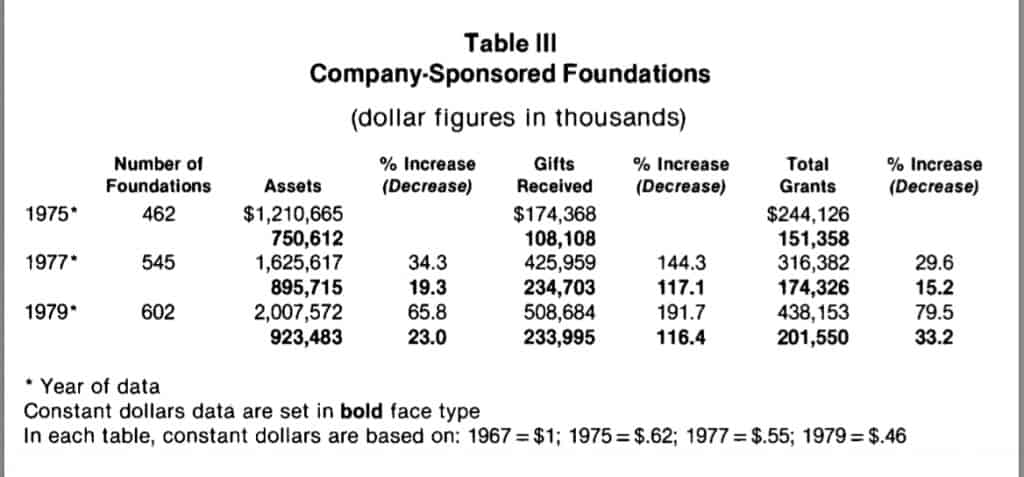

The assets of the relatively few community foundations show a 12 per cent decline in real value over four years, even though curent dollar value rose 18.8 per cent. Gifts are also down 22 per cent in the four-year period in constant dollars and up only slightly to 5.3 per cent in current dollars. Grants in current dollars are up 48 per cent compared with the 1975 data, but up only 9.7 per cent in real value. As a group, community foundations appear not to be able to attract new money easily, even though federal regulations allow them maximum deductibility for gifts. In this analysis and in Table II we have excluded from assets and gifts received an exceptionally large gift to the San Francisco Foundation which was the amount of $284 million (Leonard and Beryl Buck Foundation).

Company-sponsored foundations show a record of remarkable growth compared with independent and community foundations. Table III shows that during the four-year period, company-sponsored foundations have registered a 65.8 per cent increase in assets measured in current dollars, and a 23 per cent increase in constant dollars. Gifts for endowment or current grantmaking, comparing 1979 with 1975 figures, have gone up 192 per cent in current dollars and 116.4 per cent in constant dollars. Grants are up 79.5 per cent in current dollars and 33.2 per cent in constant dollars. Corporations are spending much more for charitable purposes through their foundations.

If figures were available for the corporate contributions of this group outside their foundations, the total might be several times the figure for the companysponsored foundations alone.

Corporations committed to using the foundation instrument have the means, in today’s climate, to overcome the effects of inflation on assets. Commonly, company-sponsored foundations do not hold assets for endowment but disburse most new money received in a relatively short period. They are not, therefore, constrained by payout requirements, nor are their corporate sponsors affected by limited tax deductibility, as might be a wealthy individual who considers making a gift to an independent foundation. Thus, a private foundation in a corporate setting is not subject to the same fiscal uncertainties as an independent foundation or community foundation, either of which usually must rely on individual donors of considerable means for new gifts. Company-sponsored foundations are affected by the rise or fall of corporate earnings, but despite fluctuations, the current trend in corporate giving is upward.

Like other institutions and organizations, today’s foundations are plagued by the problems caused by inflation. Though foundation assets have nearly doubled in current dollars over the last 15 years, their value in terms of constant dollars has declined by over 15 per cent.

The slow but steady decline in the effective giving power of these private foundations is of particular concern today, at a time when nonprofit organizations are hard hit by inflated costs of operation and the prospect of diminishing government support.

For further information write for:

Foundations Today

The Foundation Center 888 7th Avenue New York, New York 10106

Prepaid $1.50 (U.S.)

Appendix C

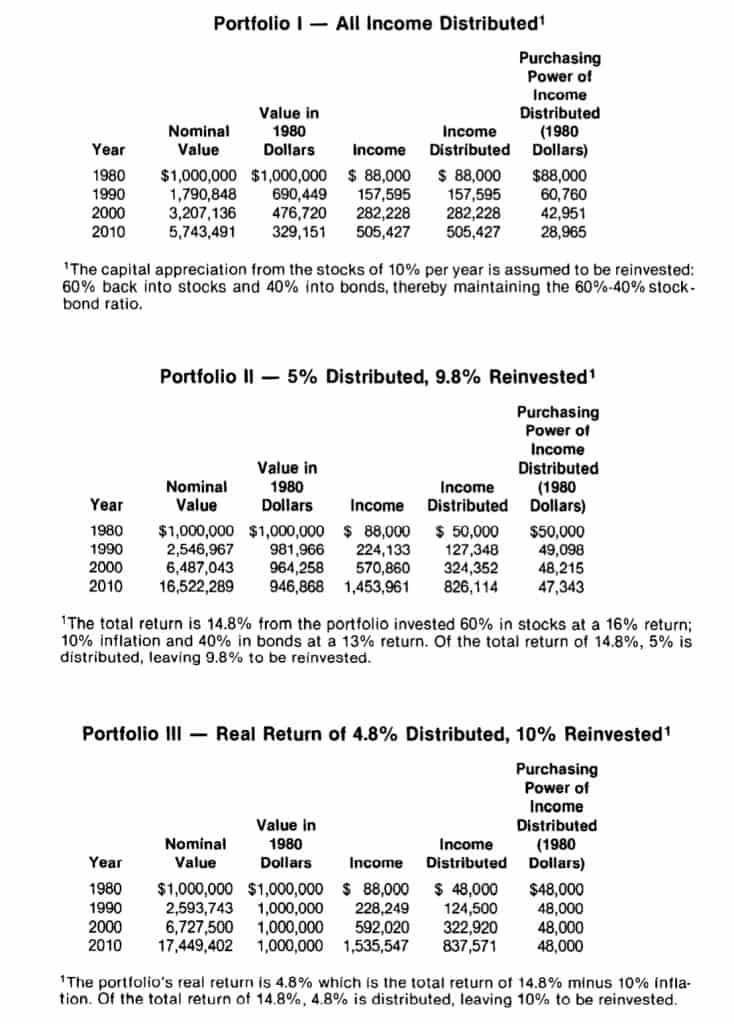

Effect of a 10% Rate of Inflation on 60% Stock/40% Bond Portfolios with Different Income Payouts The following tables illustrate the effect of a 10% rate of inflation on the constant dollar portfolio value and the purchasing power of income developed from three 60uJo stock/40% bond portfolios. The portfolios are invested to provide a total return of 14.8%, with the bonds returning 13% and the stocks 16% per year. In the first portfolio, all income is distributed; in the second, 5% of the value is distributed and 9.8% reinvested in 60% stocks/40% bonds earning at the same rates of return; and in the third, the real return of 4.8% is distributed and 10% is reinvested 60% stocks/40% bonds earning at the same rates of return.

Assumptions:

(1) All portfolios begin with $1,000,000 invested 60% in stocks to return 16% (6% real return and 10% inflation) and 40% in bonds to return 13% (3% in real return and 10% inflation).

(2) The rate of inflation is assumed to be 10% per year.

(3) The dividends from stocks provide a cash income yield based on market value of 6% and the interest from bonds provides a cash income yield based on market value of 13% for an overall cash income yield of 8.8% (60% stocks/40% bonds).

(4) It is assumed that bonds will provide a real return of 3%, although this is somewhat higher than historical returns.