In her new book, Encampment: Resistance, Grace, and an Unhoused Community, Helwig tells the story of the encampment that formed on the grounds of her Toronto church during the pandemic, and how the church and the surrounding Kensington Market community fought to protect it and its residents.

In the more than two years that an encampment was beside the Toronto church where she is the rector – Church of Saint Stephen-in-the-Fields, in the Kensington Market neighbourhood – Maggie Helwig was confronted with many unsettling questions, which she recalls in Encampment.

A community member asks: “My landlord is taking down the door of my room and telling me it’s an Airbnb now, what can I do?” A mental health officer says, “Have you tried, like, a fresh start? Like just dropping [encampment residents] in Hamilton and seeing what happens?” And, more than once, residents ask: “Where will we sleep tonight?”

There are also empathetic questions, like what do encampment residents need, why are so many people homeless, and what can we do about it? So many questions with the same answers: people need housing and income, to be treated with dignity, to have their basic needs met.

In Encampment, Helwig casts an unapologetic gaze at how our government and society fail to provide homeless people with the basic necessities of life, spotlighting the beliefs and rationalizations that lead to these failures, and the dire implications for the health and well-being of unhoused people.

Encampment is not a book of policy recommendations – though Helwig does include a few. It’s a story about the real human lives and stories of encampment residents who, in spite of being systematically marginalized and ignored, succeed in building a community of care and stability. It’s a book that says the quiet part out loud about the impact of the financialization of our housing market and lack of political will to fix it. It’s a narrative that bursts with truth, humanity, and grace. And it’s the story of people who are trying to find peace, solidarity, and understanding on all sides of the homelessness crisis.

Being afraid of something that’s deeply unfamiliar to you is very natural. It can be hard to separate the feeling of being afraid from understanding whether or not you’re actually threatened.

Maggie Helwig

People like the neighbour who, upset by shouting in the encampment one night, tells Helwig she doesn’t want to be someone who turns against vulnerable people, but the scenes she’s witnessing in the encampment are provoking those feelings in her. “Being afraid of something that’s deeply unfamiliar to you is very natural,” Helwig told me in April, when I asked her about the fear response people have when confronted with encampments. “It can be hard to separate the feeling of being afraid from understanding whether or not you’re actually threatened. We don’t learn to separate those things – at least people with privilege don’t. It’s very rare that I’m able to have conversations with people where they can de-escalate themselves enough to talk about these things.”

Thankfully, Helwig’s uncomfortable neighbour does de-escalate. By the end of her conversation with Helwig, she decides to confront her fear and anger and volunteer with the church’s meal service so she can better understand the realities of encampment residents.

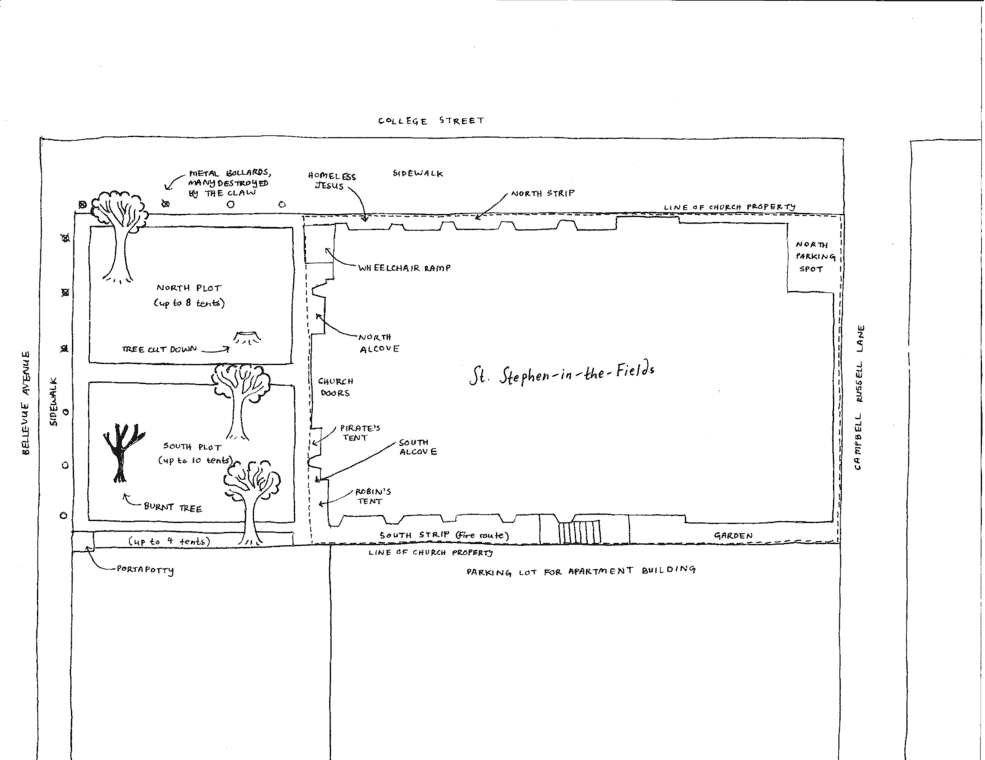

The Saint Stephen’s encampment formed in 2020 after the City of Toronto enacted pandemic measures and shut down its Out of the Cold network, which had operated 16 sites that provided 14,000 shelter beds and 35,000 meals daily. The network never reopened. Encampments grew. In 2021, the church site was one of 370 encampments in Toronto. At the church, encampment residents found a safe and non-judgmental space that provided drop-in meals and was close to other social supports.

Helwig has made a life of confronting injustice and advocating for people experiencing marginalization. She became the priest at Saint Stephen-in-the-Fields in 2013, bringing a personal commitment to social-justice activism to a church with a history of community advocacy and support, and a commitment to involving community members in challenging the systems and beliefs that keep people in poverty.

“Right through Scripture, the one thing that is absolutely clear and consistent is that the characteristic actions which God commands of us are to feed the hungry, house people without shelter, free prisoners, shelter refugees and strangers, and care for the vulnerable,” she says. “And if you read the Prophets, it’s very clear that those basic commands also mean challenging the structures which keep people hungry, homeless, and fleeing from country to country.”

The surge in the number and size of encampments during the pandemic was alarming to many. Some people rallied to form encampment support groups to provide food and clothing and other items. Others mobilized against encampments, seeking to dismantle them. The issue quickly became politicized, with encampment residents caught in the middle.

It’s not the people [sleeping outside in tents] who are bad. These people are surviving as well as they can in a really quite evil system.

Maggie Helwig

While from the outside, encampments may seem like a horror to some people – disorganized places rife with violence and drug use – what Helwig came to see there over time was a site of grace where people were surviving and supporting each other in a situation of great affliction. “I’m not saying that I think it’s good that people are sleeping outside in tents in the extreme cold, with rats around them,” she says. “What I’m saying is that it’s not the people who are bad. These people are surviving as well as they can in a really quite evil system. None of us want things to be this way, but you can’t just make things not be that way by making them not be there. And I do think where a lot of people are defaulting is they’re trying to make their own feelings of discomfort go away by making homeless people go away.”

In Encampment, homeless people are the main characters. We meet The Artist, who makes collages of found materials; Jeff, who always tries to find new arrivals a place to sleep; Robin, one of the encampment’s first residents, who finds enough of a stable home there to be able to begin to trust other people; and Pirate, who’s also known as the Verger for his role as the unofficial caretaker of the encampment.

Helwig says she wrote Encampment because she felt she was in a position to communicate some of the realities of people’s lives and people’s struggles, people who are usually misunderstood and misrepresented, and to help to show them more fairly and more accurately to the world. She has done that consistently over the past several years, using the church’s communications channels and the media to raise awareness of the encampment and the issue of homelessness.

“I think the biggest misunderstanding people have is that people are in encampments voluntarily. That they’re doing it because it’s somehow fun. Or to make a political point. Or because they don’t want to go into housing because they’re mentally ill drug addicts who would rather do drugs,” Helwig says. She points out the obvious fallacy: “If all you want to do is do drugs, and if there were housing on offer, you could go into the housing and do drugs there, as many housed people do.”

I think the biggest misunderstanding people have is that people are in encampments voluntarily. That they’re doing it because it’s somehow fun.

Maggie Helwig

But of course, there isn’t any housing out there for homeless people. There’s no extra emergency shelter capacity. Suggesting that there is, and that people just need to be made to go into it – a false narrative that Helwig says is reinforced by the City of Toronto’s communications during extreme-cold-weather alerts – further obfuscates the real problem and the solutions that are needed.

The routine punishment and marginalization of homeless people comes up on almost every page of Encampment. There are the stupid rules and chaotic communication that encampment residents and the people who help them have to contend with: a Toronto Community Housing resident is forced to flee her apartment when it’s taken over by a gang, but she can’t go into a shelter without losing the housing portion of her Ontario Disability Support Program payment, which she needs to be rehoused. The city moves the encampment from the north to the south end of the church lawn without giving a reason, forcing residents to shift their tents a few feet. There are dozens more. “Sometimes it’s not even a dystopia because a dystopia wouldn’t be this absurd,” Helwig writes in the book.

There are also pages and pages of loss. Residents lose their pets, their belongings, their temporary shelter beds, their friends and family members, their sense of hope. The Claw, an excavator used by the city to clear encampments, shreds tents, rolls over belongings, and forces residents to relocate to other encampments – scenes that echo across media and social channels, horrifying viewers but leading to no change. The constant loss makes it difficult for residents to build relationships and trust. All there is is grief and anxiety. And little more housing.

The city dismantled the church encampment on November 23, 2023. The Claw tore down residents’ tents, and city workers erected a fence around the part of the property that is a city right-of-way and dropped concrete blocks on the lot. Helwig says residents relocated to other encampments for a while, but some have been returning, setting up tents on the narrow parcel of church-owned land directly adjacent to the building.

In 2024, advocacy in some Ontario municipalities set positive precedents for the duty of care government has toward homeless people. Rulings in Waterloo and Kingston cemented into law that people experiencing homelessness cannot be evicted from encampments when there’s not enough shelter space to house them.

But in May 2025, the Ontario government reintroduced legislation that, if passed, will introduce fines and jail time for people who trespass into parks, and require people to complete mandatory drug treatment. In response, the Encampment Justice Coalition published an open letter signed by 67 community organizations that calls on Premier Doug Ford to rescind the legislation, stop punishing encampment residents, and fund housing and emergency shelter beds for the more than 80,000 people who experienced homelessness in 2024 – a number that has more than tripled since 2018.

It’s not all dark and dreary. There are good days when we come together on a project. Like right now, we’re working on housing.

Pirate, Saint Stephen’s resident

Helwig launched Encampment at the church in May with encampment residents and members of the church community in attendance, and Pirate and The Artist on stage. Someone in the crowd asked Pirate who he takes care of in the encampment. “Everybody!” he said, without hesitation. “The encampment is all about living together in peace and humanity. It’s not all dark and dreary. There are good days when we come together on a project. Like right now, we’re working on housing.”

When we spoke, I asked Helwig how she and the church community maintain solidarity in the face of the increasing divisiveness of the issue. “We talk about it all the time. We very consciously, as a church community, are trying to be a counterforce to that. We’re a very tiny community. But just continuing to try to be a community, to keep trying to look after each other, is a subversive thing to do,” she says. “There are people who come to us, not for any religious reason, but because of that. It’s about trying to be kind and vulnerable and interdependent and all the things that we’re increasingly not supposed to be.”

Helwig says she often thinks of a friend who was part of the feminist movement in Serbia under Slobodan Milosevic. “She said, I don’t even hope that I’m going to see something better in my lifetime. What we’re trying to do is just hold on to the islands of humanity so that there’s something left. Because someday things will change, and there has to be something.”

“I think that in our different ways, that’s what we’re doing,” Helwig says. “We’re trying to hold on to islands of humanity.”