The original version of this story, published in 2007, is one of The Philanthropist Journal’s most popular pieces of all time. In this updated version, Peter Elson and Peyton Carmichael expand on that detailed (and not so short) history.

The purpose of this article is to revisit an overview of the history of voluntary sector–government relations1 in Canada that was initially written for The Philanthropist Journal (then called The Philanthropist) in 2007. The original article has been revised and updated. In order to accommodate the necessary revisions and updates, original segments that addressed noblesse oblige, tethered advocacy, and a timeline on the key dates in the tax relationship between the federal government and charities have been deleted. These sections are still significant to the history of the voluntary sector and are available in the original article.

Statistics have been updated, charts revised, and the theme of Indigenous–settler relations and key developments since the end of the Voluntary Sector Initiative in 2005 have been added. This short history cannot do justice to untold stories, marginalized voices, or the hundreds of years of voluntary sector–government relations. Despite its richness, a historical perspective is often overlooked and chronically underappreciated. History provides an important contextual analysis for understanding current voluntary sector–government issues. A study of history provides a deeper understanding of the building blocks of institutions, in both government and the voluntary sector; building blocks that can make change so challenging yet also reveal opportunities when real change is possible.

This revisited historical overview will cover five dominant themes in the evolution of voluntary sector–government relations in Canada: 1) the federal state and moral charity, 2) Indigenous–settler relations, 3) a political and social reformation, 4) the rise of the welfare state, and 5) three waves, concluding with some lessons from history.

GET the Article PDF

This “short history” is, in fact, 52 pages! You can access the full document in PDF format for easy reading.

Contents

- The federal state and moral charity

- Indigenous–settler relations

- A political and social reformation

- The rise of the welfare state

- Three waves

- Lessons from history

- Endnotes

- Christi Belcourt bio

- References

The federal state and moral charity

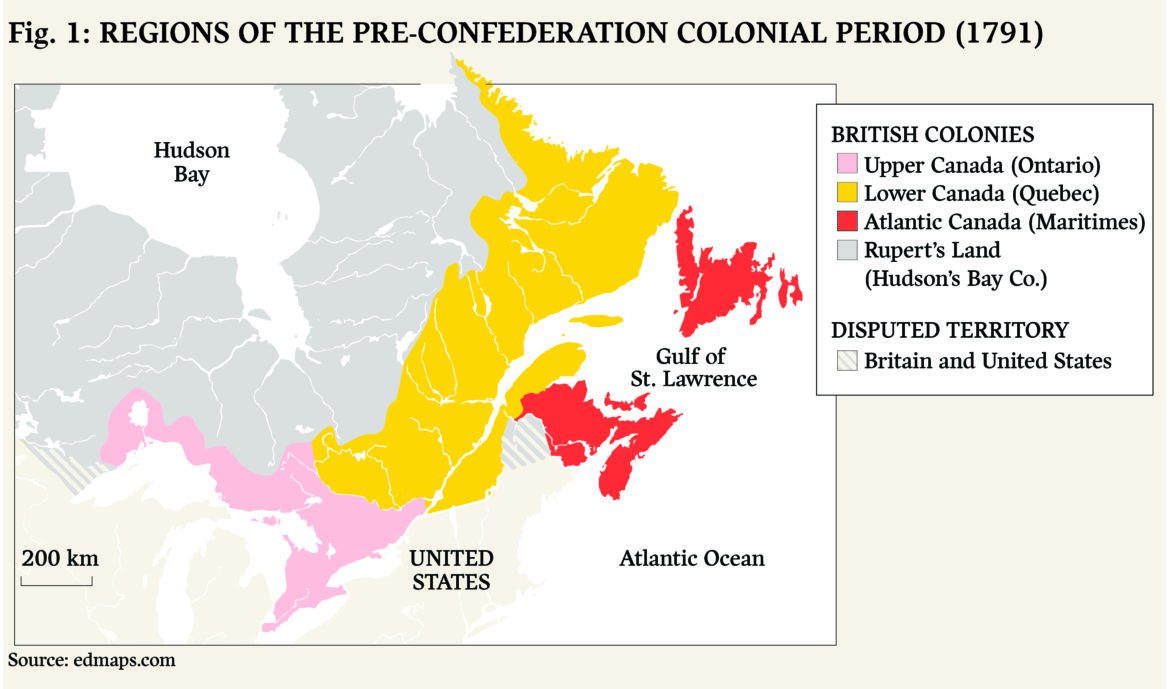

The pre-Confederation colonial period in Canada can be divided into three distinct regional trajectories: Atlantic Canada, Upper Canada, and Lower Canada (Quebec). Survival in Canada’s harsh climate and sparsely populated landscape depended on individual determination, a communal spirit, and strategic political and economic alliances. These alliances were often with Indigenous Peoples, who inhabited North America for thousands of years before European explorers arrived (M.H. Hall, Barr, Easwaramoorthy, Sokolowski, & Salamon, 2005; Miller, 2018; Thompson, 1962). It was with the arrival of European settlers in Atlantic Canada, New France, and Upper Canada that formal governance structures, processes, and services, such as social services, education, and welfare, started to take shape. The shape of these structures and services was dominated by faith-based organizations and local voluntary capacities rather than any sustained support by governments at the provincial or federal level (Marshall, 2021).

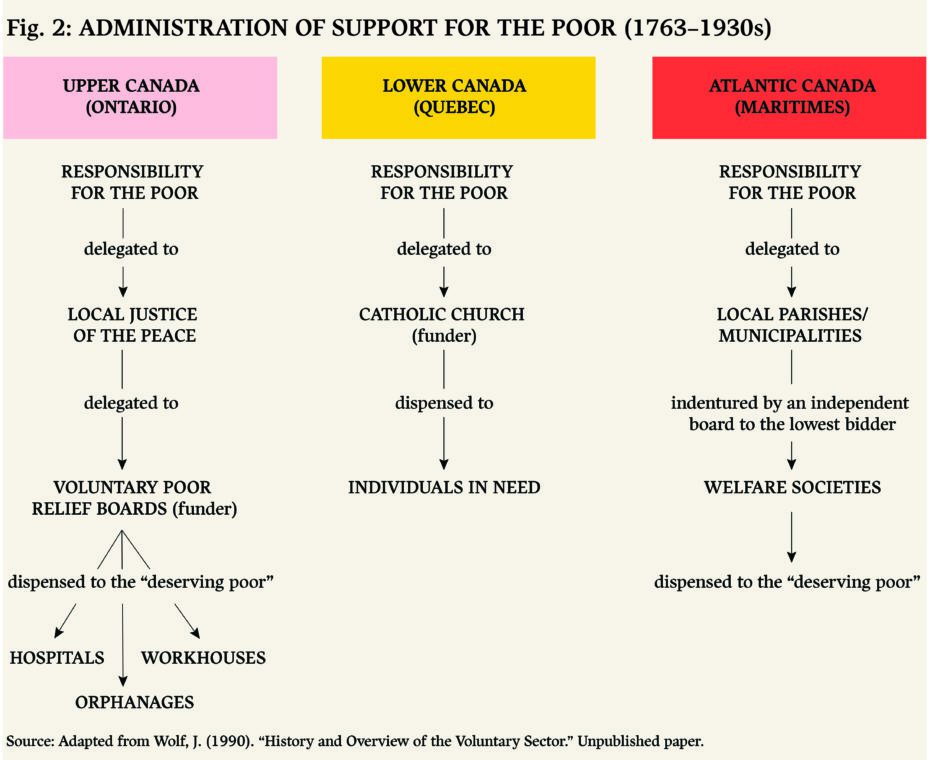

Atlantic Canada

The Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601 was imported into the American colonies and from there into what is now New Brunswick by the Empire Loyalists. The Poor Law, which obligated municipalities and counties to collect funds for the relief of the indigent and ensure the provision of asylums and other related institutions, took effect in Nova Scotia in 1763 and in New Brunswick in 1786 (Whalen, 1972) (See Figure 2). At the time, this arrangement was supplemented by provincial funds only in the case of an extraordinary emergency, such as a serious fire that resulted in widespread homelessness or an outbreak of typhoid fever or cholera (Moscovitch & Drover, 1987). Samuel Martin, in his seminal book, An Essential Grace, cites the purpose of the Halifax Poor Man’s Friend Society as typical of the private charity organizations created in this period, namely to relieve the distress of the poor with a supply of wood and potatoes during the winter (Martin, 1985).

The administration of the Poor Law in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia became the stuff of Charles Dickens, as little differentiation between deserving (i.e., aged, sick, etc.) and undeserving (able-bodied) poor was made, and support was contracted out by the municipality to the lowest bidder, extended at times to a humiliating annual public auction of paupers (Fingard, 1975). This practice, continuing throughout the 1800s, included indentured children shipped to Canada from England. Some children were embraced by families, but in other cases they were literally worked to death (Simpson, 2011). (A more compete analysis of this period was published in Elson, 2011).

By the mid-19th century, these charitable organizations, like their counterparts in Great Britain, sprang up by the dozens; charities affiliated with churches, ethnic groups, and special interests became associated with social status and moral reform and served to provide aid to those in need (Davis Smith, 1995; Martin, 1985).

New France (a.k.a. Quebec)

From the beginning of the 1600s, with the arrival of Samuel de Champlain, organized support for people in need followed traditions and edicts carried over the Atlantic from France. New France was guided by the strong and paternalistic hand of King Louis XIV, who believed not only that he was the state, but that the state must safeguard the legitimate interests of all ranks in society (Martin, 1985). In order to establish a thriving colony, the Crown gave priority to the “general good” over the individual; in other words, collective solidarity was valued over widespread individualism.

Support for people in need was in no small measure provided by the Catholic Church. Hospitals, a Bureau of the Poor, almshouses, and schools were all administered by the Catholic Church and were funded through individual donations, dedicated fundraising, and crown subsidies (Martin, 1985; Reid, 1946). The first Quebec hospital, the Hôtel Dieu, was established in Quebec City in 1638 by Superior Mother St. Ignace; le Bureau des pauvres was established in Quebec City in 1685; and la Maison de providence was established in Montreal in 1688, as was the Hôpital General in 1693 (Bélanger, 1998; Wallace, 1948). There was also a divine purpose in the provision of all these human services. The conversion of Indigenous Peoples, and later of lapsed French Canadians, to Catholicism was the underlying raison d’être for work of these organizations.

| The papal bull “Inter Caetera,” issued by Pope Alexander VI on May 4, 1493, played a central role in the conquest of the New World. It stated that any land not inhabited by Christians was available to be “discovered,” claimed, and exploited by Christian rulers and declared that “the Catholic faith and the Christian religion be exalted and be everywhere increased and spread, that the health of souls be cared for and that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself.” This “Doctrine of Discovery” became the basis of all European claims in the Americas, including Canada, and has been used to justify acts of genocide, land appropriation, and court judgements against Indigenous Peoples (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, n.d.). |

The Catholic Church in New France assumed the traditional role it performed in Catholic France, and activities that would otherwise be performed by the state (Bélanger, 1998). Thus, the Church was involved not only in the provision of all socio-economic services as well as medical care and education, but was also intimately involved in frontier exploration, colony governance, the recruitment of colonists, and the establishment of missions and cities (Bélanger, 1998; Eastman, 1915; Reid, 1946).

For all intents and purposes, the Catholic Church during the period 1608 to 1763 in Lower Canada (i.e., Quebec) was the state (Bélanger, 1998). The dominance of the Catholic Church over religious affairs as well as affairs of state is exemplified in the 1627 charter to the Company of New France. The charter stipulated that only Roman Catholics should be sent out to New France; this stayed in effect during the entire period of French rule in Canada (Wallace, 1948) and ensured the dominance of the Catholic Church in Lower Canada, which lasted for more than 300 years.

When a civil government was first established in New France in 1663, the Church became subordinate to the state, but its strength was not significantly diminished. With this subordination came a number of important institutionalized privileges for the Catholic Church, such as its official support from the state as a de facto “national church” and regulations that ensured the dominance of the Church and its clergy. This position was consolidated even further with the Quebec Act of 1774 (Bélanger, 1998). The Catholic Church in Quebec may have lost some of its influence and access to financial resources after the British Conquest of 1763, but even this was short-lived.

A new sense of laissez-faire liberalism, fuelled by an emerging class of lawyers, notaries, doctors, and land surveyors, failed to take root and consequently positioned the Catholic Church to take on an even stronger role in Quebec society. During the late 1800s, full (i.e., state-funded) guarantees were extended to confessional or religion-based schools, the only type permitted in Quebec; all civil registries were kept by the Church; only religious marriages were acceptable; Church corporations were not taxed; and the tithe was legally sanctioned (Bélanger, 1998).

At this point, the Catholic Church controlled all education, health services, and charitable institutions in Quebec. This control was augmented by the French language, which served as a strong barrier to the spread of liberalism/secular ideas from the Americans to the south and the Empire Loyalists to the west and east (Clark, 1968). In the early to mid-1900s, the Church consolidated its hold on society through its control of classical colleges and French Catholic universities and the creation of elite associations, Catholic social movements, unions, and mass-media outlets (Bélanger, 1998). It was only in the early 1960s that the “quiet revolution” would reverse and nationalize the previous dominance of the Catholic Church over the provision of health, education, and social services.

Yet the die was cast in as much as Quebecers appear to have substituted the state for the church as the primary provider of social and community services, and taxes rather than tithes as the means to fund these services. As a result, the province of Quebec has a robust social welfare system, including low-cost universal childcare, and a higher tax rate, less pronounced income inequality, and a lower donation rate compared with other provinces (Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, 2021; Lefèvre & Elson, 2020; Li, Palacios, & Fuss, 2020; Statistics Canada, 2021).

Upper Canada (a.k.a. Ontario)

The Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the old province of Quebec into Lower Canada and Upper Canada and perpetuated the influence of the Catholic Church in Lower Canada. It also sowed the seeds for a much more diverse approach to supporting the needy in Upper Canada (R. Hall, 2019; see Figure 2). For example, grants to private welfare organizations in Lower Canada were given only to religious affiliated organizations, while in Upper Canada funds for hospitals and workhouses went to independent boards that operated in municipalities (Martin, 1985).

The Constitution Act of 1867 continued to exclude the Poor Law from Upper Canada. There are a number of possible reasons for this. Moscovitch and Drover (1987) feel that it was excluded because there was the perception that there were abundant opportunities for employment, including access to land, and only municipal grants for the deserving poor (e.g., asylums) were required. The result was an institutional shift of public responsibility for the poor from the state to the individual, the family, and private philanthropy. This is not to diminish the pioneering spirit of both immigrants and the rapid influx of United Empire Loyalists and their communal strength, but poverty was seen by many at the time as a consequence of moral failure rather than any acknowledgement of structural or seasonal shifts in employment opportunities (D Guest, 1987; O’Connell, 2013; Valverde, 2006).

This abdication of responsibility by the central government did not diminish the need for charities to address those who were sick or destitute. Reluctantly, there was a gradual resumption of public responsibility for certain categories of need and a sharing of responsibilities with voluntary organizations. In a refrain that would often be repeated, the early 1800s found charities in Upper Canada establishing social welfare programs, and then requesting government support as unmet needs outweighed their organizational capacity. Ironically, the existence of a Poor Law would have made it very difficult for charities to appeal to the government for any additional funding (Valverde, 1995).

Indigenous–settler relations

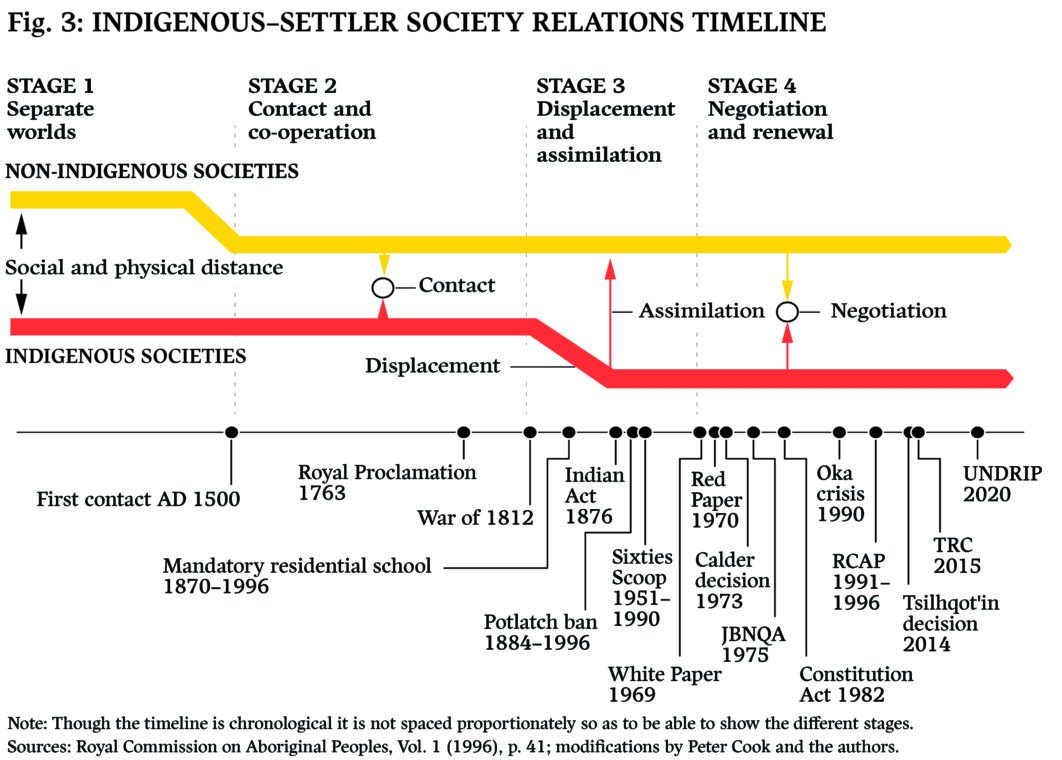

Thanks to the work of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples2 that operated from 1991 to 1996, we have a framework to understand the broad history of Indigenous–settler relations in Canada. Figure 3 below provides a four-stage analysis: separate worlds, contact and cooperation, displacement and assimilation, and negotiation and renewal. The extent to which a fifth stage could be added, namely reconciliation, is an open question. One must appreciate, however, that almost 300 years of mutual respect and cooperation preceded the draconian events that culminated in the Indian Act of 1876. As we will see, throughout this latter period and ongoing to today, the charitable sector is not an innocent bystander.

| Note: It is difficult to place each stage within a precise time frame, in part because there is considerable overlap between the stages. They flow easily and almost indiscernibly into each other, with the transition from one to the other becoming apparent only after the next stage is fully under way. Nor is the time frame for each period the same in all parts of the country; Indigenous groups in Eastern and Central Canada generally experienced contact with non- Indigenous societies earlier than groups in more northern or western locations. |

Separate worlds (stage 1)

Before 1500, Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies developed in relative isolation from each other, separated by a wide ocean. There is evidence of trans-oceanic contact in both directions but only for brief periods until the end of stage 1. By this time, the physical and cultural distance between Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies had narrowed drastically as Europeans moved across the ocean and began to settle in North America.

Contact and co-operation (stage 2)

The beginning of stage 2 saw increasingly regular contact between European and Indigenous societies for a number of reasons: non-Indigenous survival; trade, particularly furs for tools and weapons; military alliances; and intermarriage and mutual cultural adaptation. This often led to cultural and political growth and innovation in multiple directions: birthing ideas, practices, and even new cultures. In some areas (particularly in the south), contact was characterized by intense brutality and violence, while in other areas, relationships were built on mutual tolerance and respect. Increasingly throughout the years leading to stage 3, however, European settlement accompanied more and more demands for Indigenous territories and incidents of conflict, leading to a steep decline in Indigenous populations due to war, starvation, and the ravages of diseases such as smallpox.

| Throughout stage 1 and much of stage 2, Indigenous nations were often geographically isolated from traders, able to dictate terms of engagement, left alone, or were able to compatibly reconcile their traditional teachings and ceremonies with newcomer practices. These ceremonies and practices, such as the Sundance and Potlatches, are rich and elaborate occasions that blend communal, spiritual, and governance practices and protocols. Relationships and reciprocity with both humans and other-than-humans are common and reflect a wholistic view of the world and the subservient nature of humans within it (Atleo, 2004; Jamieson, 2020). |

Displacement and assimilation (stage 3)

Starting in the early 1800s, and specifically following the War of 1812, Indigenous cultures that provided essential military alliances and the foundation for British North America were abandoned, and Indigenous lands in Upper Canada were flooded with immigrants and refugees. Gone was any attempt to disguise European hunger for land development and resource extraction, a period that has been coined “the policy of the Bible and the plough” (Miller, 2018, p. 207). Indigenous nations now became barriers to colonization, obstacles, and “problems” that needed to be placated and isolated. In this period, interventions in Indigenous societies reached their peak with the tenure of Sir John A. Macdonald as prime minister (and minister of Indian affairs), who negotiated treaties on behalf of the British Crown (enshrining the legal land principles of the Royal Proclamation of 1763) and implemented the draconian Indian Act in 1876, undermining any sense of Indigenous sovereignty. Macdonald’s legacy also included the public executions of resistant Indigenous leaders (e.g., Louis Riel in Regina and six Cree and two Assiniboine leaders in Battleford, Saskatchewan), enforced starvation and relocations, residential schools, and the outlawing of Indigenous cultural practices (Stark, 2016). Political and cultural practices in Indigenous nations – time-honoured ways of governance, ceremony, and reciprocity – were seen as a threat by church leaders and assimilationists alike.

This period saw an influx of religious sects whose members were not satisfied with voluntary conversions as some Jesuits had been before. These evangelists wanted to “save the savage” through wholesale assimilation. Faith groups were allies of the colonial assimilation project and either actively or passively supported displacement, relocation, and isolationist, racist, and genocidal policies, thinly disguised as “education” and “taking the Indian out of the child.”

Residential schools were established in response to the failure of training schools to assimilate Indigenous adults. While schools were negotiated into treaties and considered by Indigenous leaders as a part of cultural exchange, federal lawmakers amended the Indian Act in 1920 to make it mandatory for every Indigenous child to attend a residential school and illegal for Indigenous children to attend any other educational institution. Indigenous parents had no choice; they would be sent to jail if they didn’t give up their children. The physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental trauma this created, across generations, in individuals, families, and communities cannot be underestimated. It would not be until the 1950s that the residential school system began to be recognized for the abject failure that it was. Even then, the failure was viewed in Canadian society as more of a failure of assimilation than a systematic act of genocide. The last residential school closed in 1996. The role of Protestant and Catholic churches in running residential schools has been well documented and won’t be repeated here (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). However, it would be fair to say that the collective role of the voluntary sector in Canada’s assimilation project not only included but extended well beyond residential schools to the “Sixties Scoop,” and continues to this day in the provision of health, education, and social services (Indigenous Foundations, n.d.; Rukavina, 2021).

Fortunately, none of these interventions succeeded in undermining Indigenous sovereignty, nationhood, or their many distinct cultural, political, and social senses of distinctiveness. Nor did it undermine Indigenous Peoples’ determination to resist assimilation and conduct relations with the dominant culture in the context of their own values and international-relations protocols.

Negotiation and renewal (stage 4)

This stage in the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies, which takes us to the present day, is characterized by non-Indigenous society’s admission of the manifest failure of its interventionist and assimilationist approach. This acknowledgement is pushed by domestic and also by international forces. Campaigns by national Indigenous social and political organizations, challenges to land erasures, court decisions on Indigenous rights, sympathetic public opinion, developments in international law, and the worldwide political mobilization of Indigenous Peoples under the auspices of the United Nations have all played a role during this stage in the relationship.

The ambiguous nature of reconciliation is exemplified by Cindy Blackstock, who points to ongoing failure to lift boil-water advisories in dozens of First Nations communities and to legal challenges to a 2016 Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruling that the federal government discriminated against First Nations children on reserves by failing to provide the same level of child welfare services that exist elsewhere in Canada.

Nevertheless, non-Indigenous society in general, and the non-profit and voluntary sector in particular, are haltingly beginning the search for change in this founding relationship. The Philanthropic Community’s Declaration of Action, the land-back work of the Land Conservancy of BC, the Ontario Nonprofit Network, the Indigenous Peoples Resilience Fund, and the Arctic Indigenous Fund are some examples (Arctic Indigenous Fund, 2021; Grant & Brascoupé, 2021; Ontario Nonprofit Network, 2021a; The Circle on Philanthropy and Aboriginal Peoples in Canada, 2016). Other organizations, with appropriate humility, are naming the truth of past practices and making genuine steps to balance their mission with reconciliation (Sierra Club BC, 2019). The YMCA associations of Canada, under the leadership of Peter Dinsdale, have taken significant steps toward building and implementing their collective commitment to reconciliation, both within the organization and externally, building relationships with Indigenous communities (Monk & Global, 2020). On the other hand, philanthropic support to Indigenous-led organizations languishes at less than one-half of 1% of total foundation grant disbursements (The Circle on Philanthropy and Aborginal Peoples in Canada, 2011).

According to reports from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996), Indigenous groups’ primary objective is to gain more control over their own affairs by reducing unilateral interventions by non-Indigenous society and regaining a relationship of mutual recognition and respect for differences. Government efforts to employ “self-government” have most often – and ironically – undermined these efforts in an attempt to create a fourth level of Canadian government instead of the sense of partnership agreed upon during treaty time. Regardless, Indigenous people have taken steps to re-establish political and cultural institutions while healing from the legacies of poverty, trauma, and cycles of dominance instituted by non-Indigenous society (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996).

| We call on the voluntary sector to name and own the truth of its complicity, whether by omission or commission, in aiding and abetting either their own or government policies that have and continue to erase, marginalize, and disempower Indigenous people.3 |

A political and social reformation

While the period between the late 1800s and early 1900s has been described by some as the “golden age” of philanthropy, it was also a period of tight moral control, extensive worker exploitation, and the most violent elements of residential schools and the Indian Act (Armitage, 1988; Martin, 1985; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). A wide range of political, social, moral, and economic reform movements were established, including the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association, and social gospel movements, which promoted moral and physical well-being. These groups tackled issues related to women’s education, urban public health, and sanitation and promoted the establishment of recreational opportunities in both urban and rural areas (Moscovitch & Drover, 1987; Valverde, 2006). This moral superiority was a direct promotion of “whiteness,” colonial mores, systemic racism, and prejudice that viewed poverty not as a consequence of structural inequality, but of personal moral failure (O’Connell, 2013).

At the same time as charities were proliferating, so were other means of providing social support. Social justice aspirations and religious ideologies were integrated into service provision for much the same reason that Jesuit priests were leading explorers in the early 1600s. The Moral and Social Reform Council of Canada is a case in point. This alliance of Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Baptist churches and the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada worked together to get the federal government to enact the Lord’s Day Act in 1906 (D Guest, 1997). In this context, the “Christian” dimension of Canadian society was reinforced by laws and social and immigration policies and was actively supported by the faith-based leaders of the voluntary sector.

Until this point, citizens and religious institutions were the primary drivers of voluntary sector activities and organizations. Governments provided funding when they were obliged to under the Poor Law or its equivalent, poor relief, but otherwise saw social services as a means to control social unrest rather than a way to increase equitable access to services and opportunities (Armitage, 1988). The prevailing view of government was that social services and opportunities for employment were there for the taking, and it was only laziness or illness that stood in the way. This “hands off” approach by government was pervasive, and it was only by political or economic necessity that social action was taken. Income security measures resulting from the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 and financial aid programs for First World War veterans and their families signaled the first major entry by the federal government into the area of social security (Dennis Guest, 2013).

The proliferation of charities in this period fostered social status for their benefactors and moral servitude for their recipients. It also resulted in the creation of local, centralized governing bodies such as the public Social Service Commission in Toronto in 1912, which was designed to streamline charity work and impose a degree of administrative efficiency and accountability (Maurutto, 2005). This efficiency drive was instigated by private sector interests with a passion for Taylorism4 and created considerable tension between Social Service Commission board members and charities.

In 1914, this tension led to the dissolution of the Social Service Commission and the development of the Neighbourhood Workers Association by charities to coordinate and centralize their work. Service-delivery coordination was complemented by the development of collective fundraising agencies such as the Federation for Community Services, which was founded in 1919 and was the precursor to the United Way of Greater Toronto. By the end of the 1920s, federated fundraising organizations were formed in major centres across Canada (Maurutto, 2005).

Defining charity, take one

The Pemsel case of 1891 and the War Charities Act of 1917 served to contain the nature and level of charitable activity, statutes that continue to constrain and limit the nature and scope of charitable activity. Over time, tax regulations have modified, restricted, and expanded the level of donations, disbursement quotas, eligible donees and eligible donations, and political activities to name a few, but at the heart of charity regulations is the definition of charity itself.

The 1891 Pemsel case is still the leading judgement and interpretation of “charitable purposes” in the context of income tax legislation. Not since the Act of Elizabeth in 1601 had a clear judgement on classification of charity been delivered (Webb, 2000). Lord Macnaghten, speaking for the majority in the House of Lords (London), wrote:

Charity, in its legal sense, comprises four principal divisions: trusts for the relief of poverty; trusts for the advancement of education; trusts for the advancement of religion; trusts for the purposes beneficial to the community not falling under any of the preceding heads [1891] AC 531 at p 583 (Webb, 2000, p. 128).

This is what lawyer and researcher Kernaghan Webb notes about the Pemsel case:

Pemsel was important not only for its classification system, but also for its confirmation that the meaning of charity for trust purposes was relevant and applicable to understanding the meaning of “charitable” under the Income Tax Act. To this day, courts and administrators turn to the Pemsel decision to assist them in determinations of acceptable charitable categories (Webb, 2000, p. 129).

The 1999 Supreme Court decision Vancouver Society of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women v M.N.R. is a prime example. In their 4–3 decision, Supreme Court Judge Frank Iacobucci, writing for the majority, wrote:

Since the Act does not define “charitable,” Canadian courts have consistently applied the Pemsel test to determine that question. The Pemsel classification is generally understood to refer to the preamble of the Statute of Elizabeth, which gave examples of charitable purposes. While the courts have always had the jurisdiction to decide what is charitable and were never bound by the preamble, the law of charities has proceeded by way of analogy to the purposes enumerated in the preamble. The Pemsel classification is subject to the consideration that the purpose must also be “for thebenefit of the community or of an appreciably important class of the community” rather than for private advantage (Supreme Court of Canada, 1999, p. 3).

It was the view of the National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action at the time (1974) that the Charities Directorate “routinely refuses to register a whole range of organizations which, from a social perspective, should be registered, but which, in the CRA’s view, did not meet the common law criteria. These include organizations promoting racial tolerance, multiculturalism, sports and recreation organizations, umbrella organizations and community broadcasting groups” (Drache, 2001, p.4).

The regulatory landscape has undergone a wholesale change since the late 1990s. Starting in early 2000, the Charities Directorate committed itself to becoming more consultative and transparent. This has manifested in public and focused consultations; regular reports; increased public, professional, and academic accessibility; expanded regulatory guidance; and periodic educational initiatives (Canada Revenue Agency, 2021b; Charities Directorate, 2003, 2004; Deboisbriand, Austin, Manwaring, McCort, & Robinson, 2017).

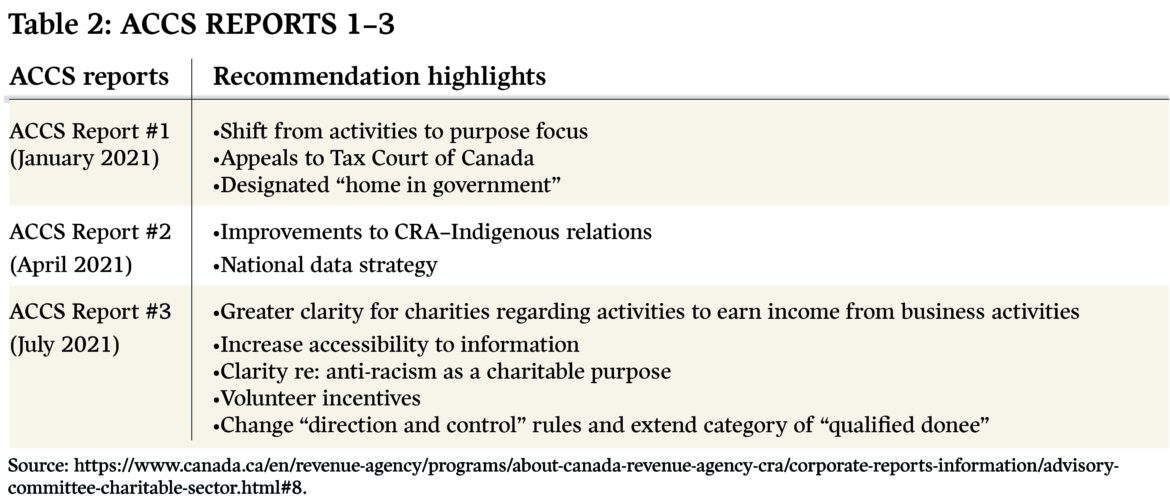

| The recently formed permanent Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector (ACCS) has been tasked by the minister of revenue to review the statutory definition of charity. This is a direct consequence of the government’s response to the Senate report on the future of the charitable sector, Catalyst for Change: A Roadmap to a Stronger Charitable Sector. |

Charities get their day

The second major event was the introduction of the 1917 War Charities Act and the Income War Tax Act. The Income War Tax Act was introduced because it becameclear to the federal government that funds needed to support First World War veterans and their families could not be raised voluntarily. The Income War Tax Actprovided unlimited income tax deductions for donations to designated war charities, such as the Canadian Red Cross, the YMCA, and the Canadian Patriotic Fund. The same year, in order to prevent the operation of fraudulent unregulated charities, the War Charities Act was introduced to register, regulate, and license approved charities (Watson, 1985).

As soon as the war was over, the war-time tax incentives were withdrawn (Watson, 1985). Although the portion of the Income War Tax Act pertaining to war charities was repealed in 1920, and the War Charities Act was repealed in 1927, the precedent had been set. A limited tax deduction (10%) for donations to hospitals, asylums, and related charities continued.

The inability of charities to raise the funds necessary to provide services only expanded during the years of the Great Depression. In the 1930s, millions of Canadians were unemployed; on the prairies, farmers were devastated by a seven-year drought (Lautenschlager, 1992). Relief was sought from local municipalities, but their source of income was property tax, which was itself limited or in default. Increasingly, provincial governments had to assume the responsibility for debt relief. Yet some provinces were themselves in financial straits, and so they turned to the federal government for support (Armitage, 1988). The federal government responded under duress to growing social unrest and subsequently increased its funding for employment relief measures and eventually passed an Employment and Social Insurance Actin 1935. Meanwhile, relief in the form of soup kitchens, bread lines, clothing depots, and shelters for the hungry and homeless were provided by caring individuals, religious groups, and voluntary agencies such as the Red Cross.

An amendment to the Income War Tax Act was moved by the federal government on May 1, 1930, and made the provision “that donations to the extent of ten per cent of the net income of the taxpayer to any church, university, college, school or hospital in Canada, be allowed as a deduction” (Watson, 1985, p.7). The debate in Parliament evolved not around the justification for the deduction, which was readily acknowledged, but around the type of organizations that would benefit (McCamus, 1996). This limited (i.e., institutional) tax provision was quickly met with vigorous opposition from community funds, federated charities, and nonsectarian charities. The act favoured Catholic charities in Quebec, which were all affiliated with the Catholic Church, over the non-sectarian charities that dominated in Ontario and the other provinces. On May 28, 1930, less than 30 days after the amendment to the Income War Tax Act was first introduced, the Mackenzie King government moved to substitute the named institutions with the phrase “any charitable organization,” as defined by British common law (Watson, 1985, my emphasis). 1930 thus marked the first time that a universal tax deduction was introduced for any charitable donation in Canada (Canada Revenue Agency, 1998; McCamus, 1996).

The rise of the welfare state

The growth of Canada in general and of the voluntary sector in particular is attributable to a number of events, including general overall economic growth; an expanding population due to rising birth rates and massive immigration; an expansion of social, health, and economic services at every level of government; and the engagement of citizens in civil society.

The specific growth of the voluntary sector after the Second World War can be traced along three policy streams: 1) a welfare state policy stream; 2) a regulatory/tax policy stream; and 3) a relational/advocacy policy stream.

The end of the war may have launched a dramatic increase in industry, the economy, and immigration, but the pervasive insecurity that marked the Depression years was never far from people’s minds. Canadians carried this legacy of deprivation with them as they were being asked to fight for Canada. Social security became a real focus of what soldiers were fighting for, and the federal government made plans to create post-war social security programs (D Guest, 1987).

This social security strategy was influenced by similar developments in Britain, where, in 1942, the Beveridge Report was released. The report made headlines not only in Britain, but across the world and particularly in North America. It captured the imagination of politicians and citizens alike. As Guest describes it, “The Beveridge Report not only addressed with unaffected simplicity and directness, the anxieties engendered in urban industrial employment, the costs associated with illness and disability, and of penury of old age or retirement” (Guest, 1987, p. 206–7). “Freedom from want” was the report’s main theme, but it also addressed disease, ignorance, squalor, and idleness. The report proposed that “freedom from want” would eventually be eliminated by a national minimum wage; disease by a universal health service; ignorance by educational reform; squalor by housing and community planning; and idleness by public planning for full employment.

A “made in Canada” version of the 1942 Beveridge Report from England was the Marsh Report (officially, The Report on Social Security for Canada), prepared by Leonard Marsh for the Advisory Committee on Reconstruction (Marsh, 1943). The Marsh Report contained six main proposals: 1) a national employment program; 2) sickness benefits and access to medical care; 3) occupational disability and care-giver support; 4) a comprehensive system of old age security and retirement benefits; 5) premature death benefits; and 6) children’s allowances5 (Marsh, 1943).

These measures were intended to contribute to postwar economic readjustment and reconstruction by providing protection to individuals and families against loss of income while also maintaining their consumer purchasing power. The Marsh Report, like the Beveridge Report, was based on the goal of achieving a society in which there was full employment, a thriving nuclear family, and cradle-to-grave social support (D Guest, 1987).

While many of these reforms were implemented, they were often done so in a piecemeal fashion, and even more often in spite of federal government support rather than because of it (D Guest, 1987). This was due to a combination of an immature federal administration, lack of public familiarity with universal social programs, federal–provincial jurisdictional issues,6 and a prevailing neoliberal political ideology (D Guest, 1987; Moscovitch & Drover, 1987). Social reforms were overshadowed by a sense of unbounded consumerism, driven by generous tax provisions for businesses and equally generous reestablishment benefits for veterans.

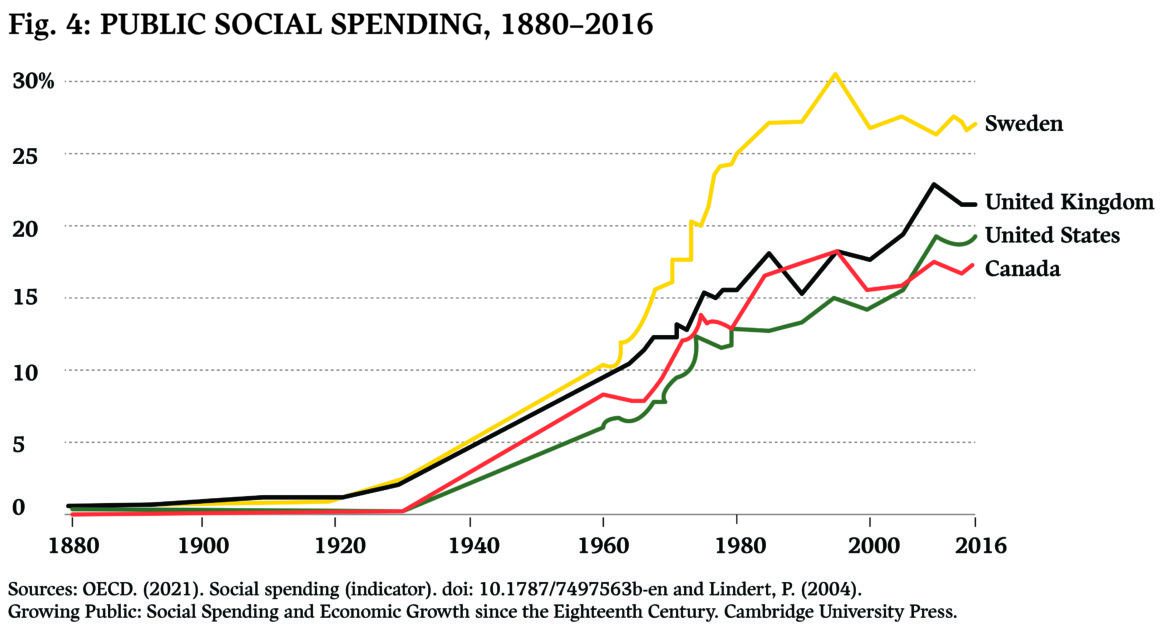

The greatest period of growth (see Figure 4) in health, education, and social services took place from the 1960s to the 1980s as social policies were implemented across a growing population and an expanding economy. The direct delivery of many services, such as hospital and home care, was provided by registered charities (M. H. Hall, Barr, et al., 2005). The relationship between charities and government social policy was synchronous in many ways and fostered the development of an interdependent partnership. Governments needed specific types of programs and services to be provided and regulated while also maintaining a “window” on community needs and trends. Compatible voluntary sector charities had similar program objectives, needed a reliable source of funds, and felt they were in a position to influence government policy (Brock, 2000).

Even today this partnership is not without tension as governments shift funding priorities and demand greater levels of accountability. At the same time, voluntary organizations demand greater flexibility to meet community needs, advocate for policy changes, and diversify their own programs to reduce their dependency on government funding (Eakin, 2007; Ontario Nonprofit Network, 2021b; Scott, 2003).

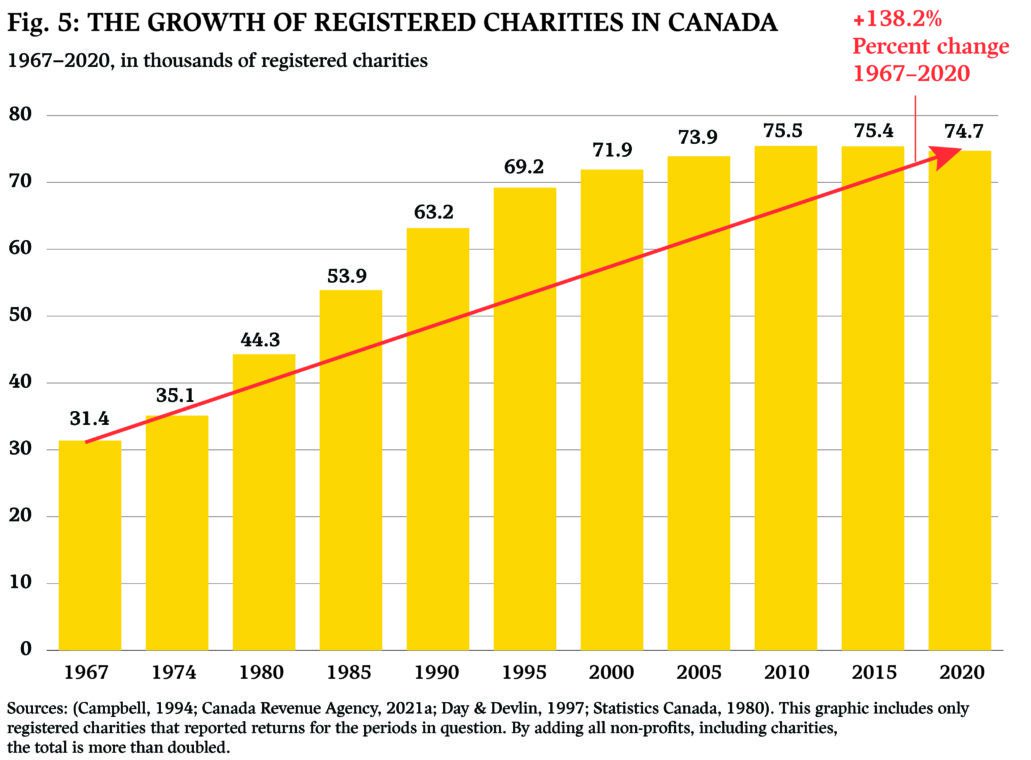

During this postwar period, voluntary organizations also became beneficiaries of government programs and continued to proliferate and to provide new services (Lautenschlager, 1992; see Figure 5). Examples include the Canadian Red Cross Society, which, supported by the St John Ambulance Brigade, started a volunteer blood donor clinic program in 1947. The Arthritis Society was established in 1948, the Canadian Diabetes Association in 1953, and the Canadian Heart Foundation in 1957. Federated appeals, once targeted to the well-off, started to appeal to the working-class. Donations to Community Chests increased eight-fold between 1931 and 1959. There is no evidence from this time that increases in taxation that were used to fund welfare services dampened people’s interest in making donations to charity (Maurutto, 2005). Tillotson has shown that throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, as Canadians were paying more taxes to fund the expanding welfare state, they were also increasing their donations to federated charities such as the United Way (Brooks, 2001).

The type and growth of registered charities has reflected direct federal and provincial government funding priorities as well as the priorities inherent in the social welfare transfers by the federal government to the provinces and territories. For example, between 1974 and 1990, the number of registered charities with a welfare focus increased by 175%; a health focus by 105%; an education focus by 221%; and a focus on general benefits to community by 170% (McCamus, 1996).

As government funding became more widely available, the number of registered charities and non-profit organizations also grew. The 1960s was a particular period of rapid growth. The decade saw a proliferation of citizens’ movements, many supported by government grant programs. Social advocates worked to gain support services and social justice for disadvantaged and disabled Canadians; women’s groups mobilized across Canada to gain women’s legal rights and push for a redefinition of women in Canadian society; and environmental advocate organizations such as Greenpeace were launched (Lautenschlager, 1992). Rather than crowding out the voluntary sector, the sector grew with and alongside government welfare services, solidifying this complex and interdependent relationship.

What Figure 5 also shows is that the reduced rate of growth of charities in the mid-1990s onward corresponds to severe retrenchment policies, funding cuts to charities and non-profits, and the emergence of a competitive contract culture. The ongoing decline in both the rate of growth and absolute number of charities may be due to a combination of voluntary de-registrations and mergers.

While the relationship between social welfare spending and the growth in the number of service-related charities and non-profits dominates the voluntary sector landscape in Canada (see Figure 5), it clearly does not paint the whole picture. Expressive voluntary organizations, such as arts organizations, sports and recreation organizations, environmental organizations, and religious organizations, are generally more financially independent, make substantive cultural and societal contributions, and are prime venues for volunteering and advocacy activities (M. H. Hall, Lasby, Gumulka, & Tyron, 2006).

Three waves

The early 1970s represents the beginning of what we have termed three waves in voluntary sector–government relations in Canada. Like any wave, it has its peaks and its troughs, because of a variety of factors – political, social, and economic.

Wave one: 1974–1995

As the number of voluntary organizations increased after the Second World War, so did their reliance on government funding. Some charities, such as Children’s Aid Societies and hospitals, received substantial government funding and were subject to accompanying directives and regulations regarding service provision. Many voluntary organizations actively pursue a “funding mix” and combine fundraising, fee-for-services, and government support to provide services, while others eschew government funding entirely. Overall, the voluntary sector receives half of its total funding from one level of government or another (M. H. Hall et al., 2006). The introduction of indirect and direct government funding, combined with federal–provincial cost-sharing programs and the sheer increase in the number of voluntary organizations over the 1960s and 1970s, brought the voluntary sector as a whole to the attention of the federal government.

In 1974, the secretary of state took two steps to try to boost the capacity of the voluntary sector in Canada: it created the National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action and supported the foundation of the Coalition of National Voluntary Organizations. In November 1974, at the inaugural meeting of the Coalition of National Voluntary Organizations, Secretary of State Hugh Faulkner announced the formation of a National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action that would take two years to study issues and problems affecting federal relations with the voluntary sector (National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action, 1977). The Council on Voluntary Action was supported by a departmental secretariat and was asked to address a number of voluntary sector–government issues. These issues included developing a workable definition of the sector, problems associated with the recruitment of volunteers and members, the financing of voluntary associations, government use of voluntary resources, and government support to advocacy groups.

According to the Council’s own report, it was prevented from exercising the full extent of its mandate. The work of the Council was hampered by outright bureaucratic resistance and a lack of access to information about the government’s own programs that affected the voluntary sector. Nevertheless, the Council’s report, People in Action, identified a number of key sectoral issues and made numerous recommendations aimed at increasing the capacity of the voluntary sector at the time. These key sectoral issues, which still sound eerily familiar today, included a) the definition of charity, b) sectoral funding mechanisms, c) simplified charitable registration procedures, d) access to data on the voluntary sector, and e) a “home in government” outside the CRA (National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action, 1977).

The absence of a well-organized representative apex voluntary sector organization, which could have distilled and prioritized the Council’s recommendations and then carried them forward, was certainly a mitigating factor in the lack of implementation of some of the recommendations. The legitimacy of the Council’s observations is reflected in the fact that many of the issues identified by the Advisory Council on Voluntary Action in 1974 were mirrored 20 years later by the Voluntary Sector Roundtable in 1995 and again 45 years later in the 2019 Senate Roadmap report (Broadbent, 1999; M. H. Hall, Barr, et al., 2005; Mercer & Omidvar, 2019).

The Coalition of National Voluntary Organizations (NVO) was also established in 1974, by several large charities at the active suggestion and encouragement of the federal government (Thayer Scott, 1992; Wolf, 1991). NVO was the only national broad-purpose sector-wide organization in Canada. It existed for nearly 15 years with nearly total reliance on government funding from the federal secretary of state’s Voluntary Action Program. It operated without a constitution or formal slate of officers and used a consensus-based decision-making style. Following a series of budget cuts and attempts at contract work, in 2006 NVO decided to wind down its operations and work with the Canadian Centre for Philanthropy to develop a new organization, which has become Imagine Canada (Imagine Canada, 2006).

Neoliberalism strikes the voluntary sector

One need look no further than the dramatic decline in growth of social welfare expenditure between 1990 and 1995 and again between 1995 and 2000 in Figure 4 to see that the welfare bubble had burst. The economic growth that had fuelled the welfare state was slowing down, and the underlying welfare state assumptions of full employment, a stable nuclear family unit, and the dependence of women started to dramatically shift as unemployment rose, families broke down, and women entered the workforce in droves (Manning, 1999).

The retrenchment of the welfare state in Canada saw a reversion to even tighter means testing (to identify the “deserving” poor), and social benefits themselves were reduced. One example was the policy of reduced unemployment insurance payments, combined with longer work period eligibility requirements (Sharpe, 2001). This combination of economic changes, political shifts to the right, and rising costs associated with a maturing welfare state combined to bring repeated calls to rein in mounting social welfare costs (Pierson, 1996).

Brian Mulroney, in a speech to the Progressive Conservative Party in 1984, was clear that one of his priorities was a complete revision of social programs in order to save as much money as possible (Brooks, 2001). This objective was to be met by encouraging the voluntary sector to participate more in the implementation of social programs. This neoconservative view was designed to promote volunteerism and the value of competitive contracting-out of government services while marginalizing citizenship rights and state obligations.

The consequence of cutbacks to the voluntary sector was a double whammy. On the supply side, governments changed or eliminated funding to programs. On the demand side, demands for services in the community increased in number and complexity (Eakin, 2001; Scott, 2003). Flexible grants to meet designated community needs were replaced by short-term contracts that involved not only adherence to strict government guidelines and reporting requirements, but competition with other voluntary or private sector organizations (M. H. Hall et al., 2003; M. H. Hall & Banting, 2000; M. H. Hall, Barr, et al., 2005). In other circumstances, organizations were (and continue to be) forced to collaborate with other organizations to be eligible for funding, even when it was less effective to do so (Brown & Troutt, 2003).

Thus, federal government support to voluntary sector organizations did not escape the drive to reduce the federal deficit, which continued unabated by the Liberals throughout the 1990s. Between 1992 and 1999, total government spending as a percentage of GDP was reduced by 20% (M. H. Hall, Barr, et al., 2005). Only the means to reduce the federal deficit changed. While the Conservatives implemented across-the-board cuts, the Liberals preferred to use selective cuts, particularly to advocacy groups (Jenson & Phillips, 1996, 2001).

This strategy served to stress the instrumental value of the voluntary sector as a means to deliver services rather than as an expressive voice for policy advocates and social justice (Jenson & Phillips, 1996). It also served to deliberately weaken the advocacy capacity of organizations that would be most critical of the cutbacks. Promoting volunteerism diffused the public impact of cutbacks, while the lack of a clear common voice for the voluntary sector only increased the sector’s overall vulnerability.

The Voluntary Action Program in the Department of Heritage Canada is a prime example of the impact of these cuts. The Voluntary Action Program had a mandate to support the growth and diversity of the voluntary sector and to strengthen the independence of the sector by facilitating access to financial and technical expertise and by developing innovative financing techniques (McCamus, 1996). Over this period of relentless cost-cutting in the early to mid-1990s, the budget for the Voluntary Action Program was reduced from almost $1 million to less than $30,000. The consequence of these cuts was that direct funding to voluntary organizations, such as the Coalition of National Voluntary Organizations, was eliminated, and the focus of the Voluntary Action Program became one of policy and research.

What makes this dynamic particularly important is that these neoliberal policies and associated accountability demands have continued unabated through changes in governments, periods of economic growth, the elimination of a federal operating deficit, growing fiscal surpluses, and a significant reduction in the national debt.

The culture of short-term, competitive, outcome-driven contracts has become institutionalized by all federal departments that have relationships with the voluntary sector (Eakin, 2001). The enrichment and liberalization of tax credits for charitable donations during this period was also a mixed blessing, for as the right hand was making it easier for the sector to solicit donations, the left hand was downloading programs and services to the voluntary sector. Typically, this downloading came with numerous conditions and rarely enough funds to completely cover the full cost of service delivery (Eakin, 2007).

Over time, these tax provisions have also contributed to a bifurcation of the voluntary sector. On one hand, 80% of voluntary organizations in Canada have no staff and revenues of less than $250,000 (M. H. Hall et al., 2006). On the other hand, there is a relatively small group of very large voluntary organizations that continue to get even larger. These organizations often provide services of key interest to governments in the areas of health, education, and social services (M. H. Hall, Barr, et al., 2005). As registered charities, these large organizations have a distinct advantage in attracting private donors, recruiting and managing volunteers, and competing for government contracts.

The service aspect of the voluntary sector continues to dominate the overall profile of the sector, while voluntary organizations that focus on advocacy tend to lack the same degree of policy relevance and credibility (M. H. Hall & Banting, 2000). The neoliberal contract culture that took hold in Canada in the mid-1990s, displacing citizenship-based project funding during a time of massive deficits at the federal and provincial level, has not been significantly modified with either the establishment of intersectoral partnership agreements or variances in economic conditions (Elson, 2011).

| What is decent work? Decent work means more than fair wages and benefits. It reflects a cultural shift that builds on the values that drive your work in your community. Decent workplaces are fair, stable, and productive workplaces. Decent work means building a culture of equality and inclusion at work, and ensuring everyone’s voices are valued and heard. Decent work means acknowledging the highly gendered nature of the non-profit sector’s workforce – and developing solutions that address women’s particular interests and concerns. Source: ONN (2021): https://theonn.ca/our-work/our-people/decent-work/ |

Wave two: 1995–2005

During the 1980s and 1990s, the voluntary sector was collectively caught in the undertow of 1) a desire for smaller government, 2) an era of fiscal constraint, 3) the growing popularity of citizen engagement, and 4) the division of constitutional responsibilities between the federal and provincial/territorial governments (Carter, Broder, Easwaramoorthy, Schramm, & de Witt, 2004). This dynamic created a voluntary sector–government relationship that deteriorated between the late 1980s and the mid-1990s. The result was mutual isolation, general suspicion, and outright antagonism on both sides. It was not until the mid-1990s that a relational shift started to take place

In the absence of a strong national organization that could speak for the sector, a group of 12 national organizations created the Voluntary Sector Roundtable in 1995 (M. H. Hall, Barr, et al., 2005; S. D. Phillips, 2003).7 Funded not by government but by a cluster of leading Canadian foundations,8 the Voluntary Sector Roundtable’s primary goals were to enhance the relationship between the charitable sector and the federal government and to encourage a supportive legislative and regulatory framework for organizations in the community (Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector, 1998). The Voluntary Sector Roundtable soon realized that to get the federal government’s attention it needed to promote sectoral accountability, good governance, and public trust (S. D. Phillips, 2003). To this end, in October 1997, the Voluntary Sector Roundtable set up the Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector (PAGVS), an arm’s length panel chaired by Ed Broadbent, the former leader of the federal New Democratic Party.

The Broadbent Panel, as it was commonly referred to, was given the mandate to explore issues ranging from the role and responsibilities of volunteers to fundraising practices and fiscal management within the sector. The Panel also examined the external regulation of the sector by governments and options for enhancing internal accountability practices (Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector, 1998). The Panel’s 1999 report, Building on Strength: Improving Governance and Accountability in Canada’s Voluntary Sector, not only laid out recommendationsfor better self-regulation and governance but also proposed steps for the federal government to take to create a more enabling environment and a stronger relationship with the voluntary sector (Broadbent, 1999).

While similar in some ways to recommendations in the 1977 People in Action report, there are three significant differences: 1) Building on Strength was funded by the voluntary sector itself, not the federal government, 2) its activities were tied to leading national voluntary sector organizations and foundations, and 3) the report outlined four immediate priorities for action: a) a good practice guide, b) the creation of a Voluntary Sector Commission, c) a review of the definition of charity by Parliament, and d) a compact of good practice between the sector and governments at both the federal and provincial levels.9

Meanwhile, on the government side of the sectoral divide, a similar mood of collaboration was developing. The Liberal Party, striving to overshadow its neoliberal fiscal policies, gave considerable attention to the voluntary sector in the 1997 election campaign program and followed through after its re-election (S. D. Phillips, 2003). This follow-through took the form of a Voluntary Sector Task Force, which was housed in the Privy Council Office. In 1999, the Voluntary Sector Task Force created three “Joint Tables” consisting of equal representation from government and the voluntary sector and joint co-chairs. The three tables had a mandate to address: building relationships, strengthening capacity, and improving the regulatory framework. The result of these three collaborative and highly productive joint tables was Working Together, a report that closely reflected many of the recommendations in the Broadbent Report and reinforced one proposal in particular: to develop a framework agreement or “Accord,” based on a similar “Compact” agreement in the UK (Joint Tables, 1999).

In June 2000, in response to the Broadbent and Joint Table reports and its own political priorities, the federal government announced the creation of the Voluntary Sector Initiative (VSI) (Elson, 2012). The VSI was a five-year, $94.6-million initiative to fund the work of seven joint tables, designed on the collaborative model created by the Voluntary Sector Task Force. These seven joint tables were 1) Coordinating Committee, 2) Accord, 3) Awareness, 4) Capacity, 5) Information Management and Technology, 6) Regulatory, and 7) National Volunteerism Initiative. In addition, two working groups on funding and advocacy were created and funded by the voluntary sector.

In its first two years (phase one), the VSI brought together equal numbers of representatives from the voluntary sector and the federal government to work at the joint tables. Each table was co-chaired by one representative from the sector and one from government. The six joint tables were 1) the Accord, 2) Capacity, 3) Regulatory, 4) Awareness, 5) National Volunteerism; and 6) Information Management/Information Technology, as well as a coordinating committee to oversee the process.

The most visible event in the first phase was the signing of the Accord Between the Government of Canada and the Voluntary Sectorto coincide with the International Year of Volunteers in December 2001 (Government of Canada & Voluntary Sector, 2001). This signing was followed by the development and wide circulation of two codes of good practice: A Code of Good Practice on Policy Dialogue, and A Code of Good Practice on Funding.

In phase two, between November 2002 and March 2005, the Voluntary Sector Initiative made recommendations on regulatory reforms for registered charities: a Canada Volunteerism Initiative to encourage volunteering; research on volunteering and giving and the size and scope of the sector, including the establishment of a National Satellite Account; and a number of human-resource-related research and policy initiatives (M. H. Hall, de Wit, et al., 2005). At this point, however, the political will that launched the VSI ran out of steam. Implementation monitoring ceased, budgets were not renewed, and responsibility for overall coordination was split between three government departments, making any horizontal coordination difficult to achieve (Elson, 2006).

Legacy of the VSI

There’s a good chance the legacies of the VSI will continue to be rewritten, depending on time and perspective. In this revisitation of the original 2007 article, three consequences of the Voluntary Sector Initiative will be profiled: the importance of data, lessons for ongoing voluntary sector–government relations, and the catalytic role of the VSI for voluntary sector–government relations at a provincial level.

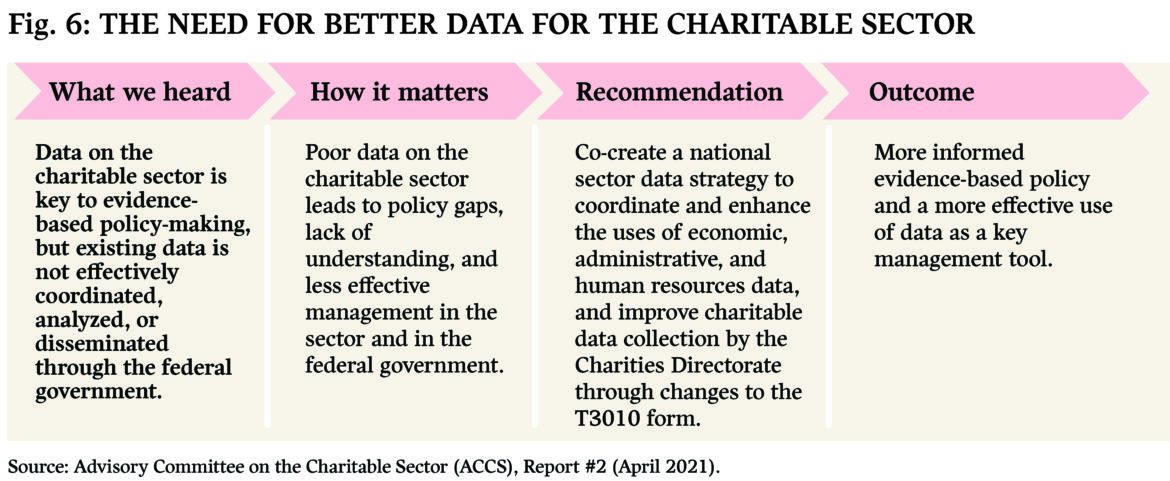

Show me the data: The first consequence of the VSI is the demonstrated capacity of the federal government to provide much-needed data about the voluntary sector when they allocate the resources to do so. This statistical report, Cornerstones of Community: Highlights of the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations, provided the first comprehensive overview of the sector since it was first attempted in 1974 (Statistics Canada, 2004). It gave both the sector and governments across Canada a new appreciation for the size, scope, and economic impact of the sector. As we will see, this had a number of unanticipated consequences, particularly at the provincial level. Cornerstones of Community was followed by a series of Satellite Accounts reports that not only updated some core statistical data across a number of years (1997–2005), but also enabled a comparative analysis across OECD countries (Statistics Canada, 2008). Unfortunately, neither the reports, surveys, or statistical analysis have continued in any consistent fashion, leaving the voluntary sector, once again, to appeal to the federal government for better data on the sector (Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector, 2021b; see Figure 6).

Shall we dance? A second consequence of the VSI are lessons to be learned about the nature of voluntary sector–government relations. While we have our own take on the VSI, we also want to build on a 2013 article in The Philanthropist by Patrick Johnston, who served as the co-chair of the Joint Coordinating Committee of the VSI. The VSI has been seen as overly ambitious and representationally flawed.

Overly ambitious: Like its 1974 predecessor, the basis for the VSI, Working Together, contained 26 recommendations. It may have been half the number of recommendations produced by the Council on Voluntary Action in 1974, but there were still too many to catch the attention of senior cabinet ministers. Even if the number of recommendations was to stay constant, they needed to be honed down to the top two or three that needed political focus and financial investment.

Two of the core voluntary sector issues, funding and advocacy, identified after months of cross-Canada consultations, were taken off the table by federal officials. Rather than stand firm, sector representatives at the time decided that a compromised relationship was better than no relationship at all (Johnston, 2013). While the non-partisan advocacy issue was resolved in 2018, full funding is still an outstanding issue, 21 years later (Revenue Canada Agency, 2019).

| Relationship lesson: Pick the top two or three priority recommendations and then proceed further when these have been addressed. |

Representationally flawed: There was a representational disconnect at the VSI between what was needed to advance public policy in a formal institution like the federal government and the number and range of people who were called on from all parts of Canada to participate in numerous joint working groups, many with little or no policy expertise. Compounding this representational deficit was the marked absence of provincial or municipal government representatives, sector leaders from Quebec, and meaningful representation from racialized, Black, and Indigenous communities. These relational disconnects led to the absence of political legitimacy for the sector and for the process as a whole.

| Relationship lesson: The greatest political credibility will come with groups that have both policy expertise and broad and deep networks that reach into communities. |

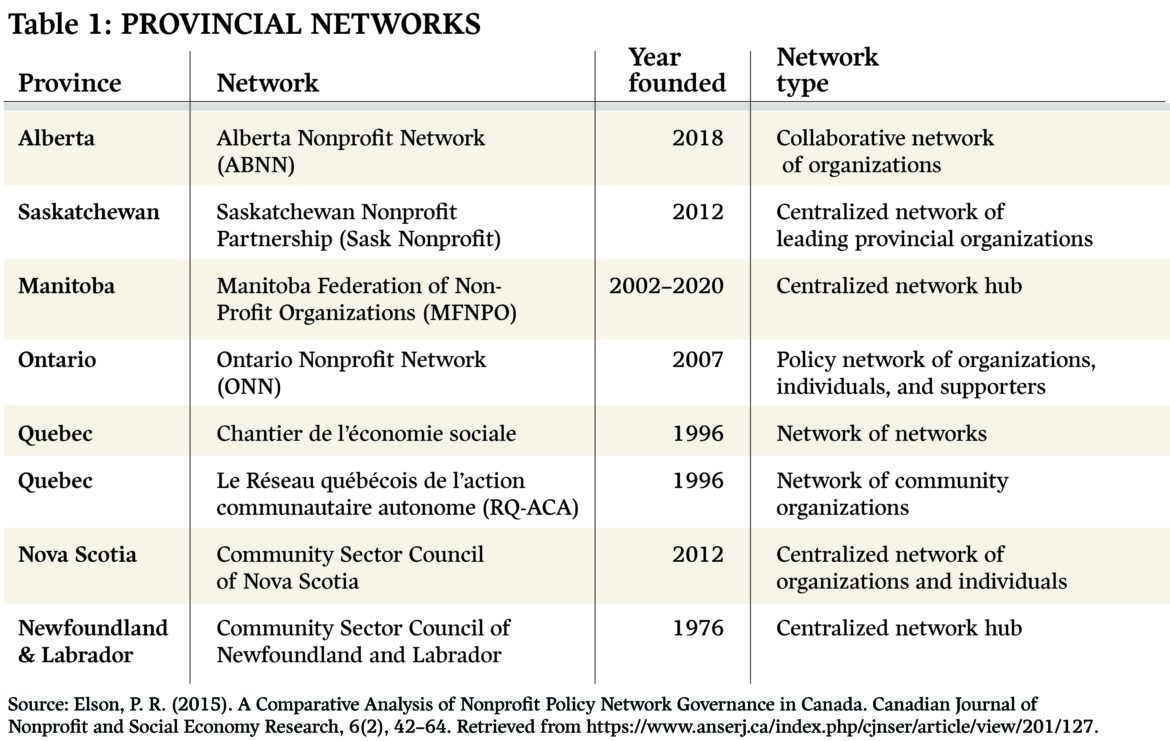

Provincial voices arise: A third consequence of the VSI was a boon in the emergence of umbrella organizations to represent and support the sector at a provincial level. The Canada Volunteerism Initiative, another component of the VSI, provided the means for many community groups across Canada to meet and identify common issues. The Canada Volunteerism Initiative was a five-year federal program introduced in 2001 to encourage Canadians to participate in voluntary organizations and to improve the capacity of organizations to benefit from volunteers (Voluntary Sector and Government of Canada, 2001). One key benefit was the allocation of funds to local voluntary organizations to engage with each other within their own region and/or province. This led to a burgeoning network of voluntary organizations at a provincial level that had previously no incentive and few resources to meet and get to know each other and the issues they had in common. The consequence of these informal networks and an awakening by provincial governments of the size and scope of the sector in their own backyard led to an increased willingness to engage and organize in ways that had not been seen before.

While VSI funding ran out in 2005, there were now provincial voluntary sector leaders who were willing to step up to the plate and provincial government counterparts who were as interested in developing an ongoing relationship. Over the next 15 years, these modest beginnings have resulted in a “third wave” of voluntary sector–government relations at the provincial level.

Wave three: 2005–2020

While a number of noteworthy events occurred between 2005 and 2020 – a severe advocacy chill in 2015; unlimited non-partisan advocacy in 2018; the entrenchment of contract culture; and the rise of social enterprises, the mega-foundation, and donor-advised funds – nothing compares to the dramatic increase in the number of provincial networks from coast to coast and their capacity to train, support, and advocate on behalf of the broader voluntary sector across their respective provinces (Elson, 2014; Elson, Hall, & Wamucii, 2016).

The deep freeze

Before we turn to the emergence of collective voices at the provincial level, it’s worth noting that as these voices were awakening, they were being silenced at the federal level. The term “advocacy chill” turned into a “deep freeze” between 2008 and 2015 for environmental organizations under the Harper government. The focus in this period, beyond myriad “friends-only” invitations to policy consultations, was the ongoing scrutiny and audits of charities by the Canada Revenue Agency. While random audits had been the status quo, with the odd complaint-driven response, charities that were in a position to challenge government in general, and environmental groups in particular, came under intense scrutiny, intimidation, and potentially charity-status-revoking audits. Fuelled by complaints from groups such as Ethical Oil, up to $13.4 million was allocated between 2008 and 2014 for such a purpose (Healy & Trew, 2015). The attacks didn’t stop at environmental groups: it wasn’t long before human-rights and anti-poverty groups came under fire too. This “deep freeze” extended well beyond CRA audits to outright surveillance and privacy violations on Indigenous groups and nations. No wonder there was an appetite for organizations at a regional and provincial level to distance themselves from the federal government and build relationships closer to home.

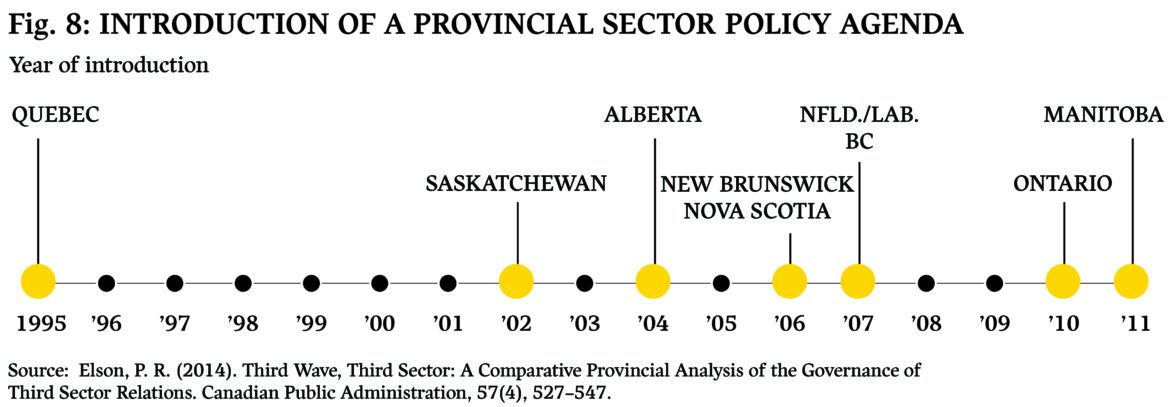

Provincial voices awaken

In 2001, with the exception of Quebec,10 there was no articulated policy agenda for the collective voluntary sector in any province.11 By 2011, seven of 10 provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador) had an affiliated minister or deputy minister responsible for the relationship of the provincial government with their voluntary sector. And by 2012 two other provinces, Saskatchewan12 and New Brunswick, had established bilateral policy forums with the community-human-services segment of the voluntary sector.

Some of this change has been driven by the mutual recognition of a substantial and hidden relationship, brought to light, in part, by the 2005 National Survey of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations.13 In other cases, provincial issues of poverty, unemployment, fiscal austerity, and an uncoordinated and under-resourced service-delivery system brought the government and voluntary sectors to the policy table.

The burgeoning sectoral policy relationship that developed relatively simultaneously across multiple provinces was based on a number of common issues. Many of these issues, particularly those related to funding, human resources, capacity building, and volunteer management, were profiled in reports related to the Voluntary Sector Initiative (Human Resources and Social Development Canada, 2009; Social Development Canada, 2004).

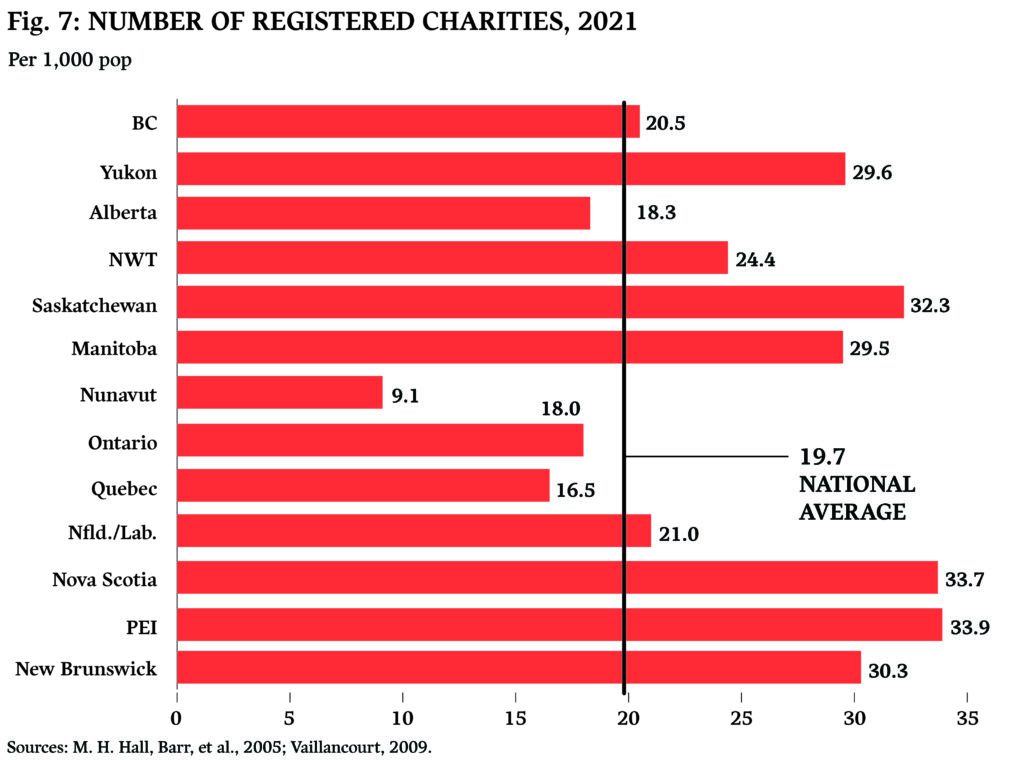

The knowledge that these issues existed was not new to either the non-profit sector or provincial governments. While provinces did not participate in the VSI, they certainly monitored its progress and were keen readers of the many reports that emerged from the five-year process. The national survey, for example, helped to elevate non-profit policy discussions from anecdotal stories to systemic governance issues, particularly when placed in the context of the dominant role Canadian non-profit organizations play in the delivery of human services (M. H. Hall, Barr, et al., 2005; Vaillancourt, 2009; see Figure 7).

During the third wave, eight of Canada’s 10 provinces (see Figure 8) initiated agendas to address issues associated with their voluntary sectors. Only in Quebec did community activists, social economy actors, and corresponding provincial government ministries undertake relationship-changing policy initiatives, independent of the VSI. Whereas the VSI was driven by a desire to improve the relationship between the federal government and the voluntary sector across a number of issue areas, including funding, governance, and accountability, the policy agenda in Quebec was driven by a desire to reduce or eliminate the high levels of unemployment and poverty (Broadbent, 1999; Mendell, 2003).

Another characteristic of the third wave of policy dialogue has been the emergence of formal bilateral policy forums designed to address crosscutting issues. This was the case with British Columbia’s Government Non Profit Initiative (GNPI; 2007–2012) and the Alberta Non-Profit/Voluntary Sector Initiative (ANVSI; 2006–; see Table 1). An informal version of a government-sponsored bilateral policy network exists in New Brunswick with the Community Inclusion Committees, established by the Economic and Social Inclusion Corporation (Economic and Social Inclusion Corporation, 2011).

Six of 10 provinces (Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia) initiated voluntary sector–provincial government policy agendas following the completion of the VSI. Two provinces, Saskatchewan and Alberta, initiated their own policy initiatives while the VSI was still underway. In 2002, Saskatchewan’s Premier Lorne Calvert launched a Premier’s Voluntary Sector Initiative, co-chaired by the legislative secretary to the premier and a voluntary sector leader (Hamilton & Mann, 2006). In 2004, a group of leading voluntary sector organizations in Alberta initiated a “Leaders Group” that eventually became the ANVSI, again co-chaired by representatives from the provincial government and the voluntary sector (van Kooy, 2008).

Other provinces have clustered or decentralized policy network structures because of the existence of multiple non-profit policy networks. In the case of British Columbia, the Voluntary Organizations Consortium (VOCBC), Board Voice, and Volunteer BC maintain an informal liaison between key actors. In Alberta, the level of liaison and systematic policy coordination among the Calgary Chamber of Voluntary Organizations (CCVO), the Edmonton Chamber of Voluntary Organizations (ECVO), and Volunteer Alberta reflects a more structured and formalized relationship. This relationship took on a broader and more cohesive tone in 2018, with the creation of the Alberta Nonprofit Network (ABNN).

Other provinces developed more centralized policy networks, independent of government, through either formal or informal sector-wide networking structures. Examples include the Alberta Nonprofit Network (2018), the Saskatchewan Nonprofit Partnership (2012), the Ontario Nonprofit Network (2007), Le Chantier de l’économie sociale (1996), Le Réseau québécois de l’action communautaire autonome (RQ-ACA; 1996); and the Community Sector Council of Nova Scotia (2012).

The existence of individual or collective non-profit sector representation, while necessary for a sustainable policy dialogue to be established, is not sufficient. Political will on the part of governments is also required, and this willingness appears to be tied to the alignment of the non-profit sector to poverty reduction, community economic development, service delivery, and, to a lesser extent, volunteerism (Elson, 2011).

Lessons from history

The contemporary status of voluntary sector–government relations can be divided into four areas that are also decades old, and thus history has some lessons to contribute. These four areas are 1) defining charity, 2) fostering policy consultation, dialogue, and communication, 3) funding retrenchment policies, and 4) decolonizing the voluntary sector.

Defining charity, take two

The most significant tax benefit for the voluntary sector is the advantage associated with having charitable tax status, regulated through the Income Tax Act. There continues to be a call for the modernization of the definition of charity and its regulation outside the Canada Revenue Agency, as first recommended by the National Council on Voluntary Action in 1974 and as recently as the 2019 Senate Roadmap report (Bridge, 2002; Broadbent, 1999; Drache, 2002; Mercer & Omidvar, 2019). Even those who have defended the use of the Preamble to the Act of Elizabeth in 1601 call for a more sophisticated interpretation by the Charities Directorate. For example, both Scotland and Britain have modernized the definition of charity and defined “substantially all” as 51% of resources. Beyond the standard four pillars of charity, charitable activities in England and Wales now include the advancement of amateur sport; human rights, conflict resolution or reconciliation or the promotion of religious or racial harmony or equality and diversity; environmental protection or improvement; and animal welfare (Charity Commission for England and Wales, 2013). Meanwhile, to date, Canada’s federal government has resisted calls to do the same (Bellingham, 2006; Drache, 2002; House of Commons, 2005; Scottish Executive, 2004).

In Canada, because there is no statutory definition of what constitutes a charity, it falls to the courts to determine, based on the common law, whether an organization’s purposes make it a charity. In the case of an organization seeking federal registration as a charitable organization or foundation, this determination is made by the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA; Broder, 2011). The Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector (ACCS) has recently recommended that appeals be allowed to go to the Tax Court of Canada, in order to expedite the appeal process (Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector, 2021a).

In March 2006, the Canada Revenue Agency issued CPS-024, Guidelines for Registering a Charity: Meeting the Public Benefit Test, in which it indicated that it may consider new purposes charitable but only when the issue of what benefits the public has been altered through a change in legislation or stated government policy (Charities Directorate, 2006). The justices of the Supreme Court, in making their judgement concerning the Vancouver Society of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women, were equally clear in stating that any substantial change in the law of charity must be made by the legislature, not the court (Supreme Court of Canada, 1999).

| The definition of charity consists of two key components: the categories or “heads” of charity (e.g., relief of poverty, advancement of education, religion, and other purposes beneficial to the community) and what constitutes a “public benefit.” |