*Editor’s Note: So that readers may have the full text and Appendices of this important contribution to the current debate surrounding the restructuring of the federal laws and regulations governing the Canadian charitable sector, this article will be published in two parts. Part I follows. Part II will appear in Volume 16, Number I.

Part I1

Foreword

This article examines the desirability of having an independent federal body assume some of the key roles which Revenue Canada (CCRA),2 currently plays in the charity field, as well as offering ideas about that body’s structure and operations.

The article postulates the creation of an independent body having as its primary role the right to determine which organizations will be registered as charities for Income Tax Act purposes only. As a concomitant, it would decide which organizations Jose their registered status for failing to continue to meet the statutory and administrative requirements of the tax system. Both of these powers are now exercised by the Charities Division of Revenue Canada (CCRA).

We have attempted to identify the legislative and structural options and requirements for this kind of body. We do this to allow interested parties to move beyond the need to debate whether such a body should be created and, instead, focus on the mechanics involved in structuring it. Of course, the structuring must take into account a wide range of policy decisions. We hope that this article will further the discussion about how this function should be structured and why.

While some will undoubtedly disagree, we believe that the question of the need for change from the status quo is beyond debate. In the report entitled Working Together: A Government of Canada/Voluntary Sector Joint lnitiative3 the members of what has come to be called the “Joint Tables” put forward three options for changes in the system of federal charity oversight. The recommendations and discussion will be found in Appendix A.

Three options are suggested. The first is to retain the status quo: all power continues to reside with Revenue Canada (CCRA), albeit with some changes to make the process a more open one, aided and abetted by “a committee of knowledgeable individuals”.

The second option would see the creation of an “Agency” to “complement” Revenue Canada’s (CCRA’s) role by offering advice and to “nurture and support charities and other voluntary organizations and provide information to the public”. This option was based on recommendations in the Broadbent Report.4

The third option creates a “quasi-judicial” Commission which would “undertake most of the functions currently carried on by the Charities Division”. The concept also sees the Commission as providing authoritative advice to the voluntary sector.

The Joint Tables Report indicates that when the three options were considered, Table members representing the voluntary sector all opted for the Commission model while the government representatives were of the opinion that any of the three models would work.

As noted, the purpose of this paper is to identify the legislative and structural options and requirements for that kind of body; it is not to debate which of the models might best serve Canada. We take the position that there is no viable option to the establishment of a commission-like body.s Indeed, in our view, the “Agency” option is a complete nonstarter because it is perceived as simply adding a level of additional bureaucracy to the current system without creating a body with any power. As independent decision-makers, advisory boards in Ottawa are usually notoriously ineffective and, most often, perceived to be captured creatures, serving only as part of the government’s public relations exercise.6

We also take the position that organizational changes are extremely difficult, if not impossible. We do not believe that it is prudent to try to counteract the problems inherent in having a department dedicated to maximizing tax revenues make social policy decisions, particularly where a decision to recognize an organization as charitable de facto implies a loss of tax revenue. The Joint Tables Report suggestions of incremental changes to meet currently perceived problems smack of slapping a new coat of paint on a house which is structurally unsound.7

For these reasons, we are committed to what we are calling the Charity Tribunal. And having now acknowledged the basis for our position, we provide the guidelines within which we are working.

I. In our view, neither the Broadbent Report nor the Joint Tables Report, gives enough attention to the constitutional problems inherent in the fact that prima facie, in Canada the law of charity is a matter of provincial jurisdiction, though sparsely exercised.8 In fact, with the exception of Ontario and Alberta9 the provinces are almost completely inactive in exercising their powers of oversight in the voluntary sector. As a result, without direct jurisdiction, through its use of the provisions of the Income Tax Act the federal government has effectively become the main player in the field, forcing charities to meet certain legislated standards in order to maintain their ability to give tax relief for donations.

This article proposes that an independent body be established to make a limited range of decisions about getting and losing the status of a charity under the Income Tax Act. The Charity Tribunal would, ab initio, have very limited jurisdiction. We are assuming that it should not have powers which impinge on those of the provinces, whether or not those powers are exercised. And we are assuming that only after the Tribunal is well established in its primary roles of registering and deregistering charities and having a role in the appeal process will consideration be given to expanding its role to encompass, for example, the role of nurturer and advisor to the sector.

2. For this article, we accept the group of assumptions which are adopted in the Joint Tables Report. These include:

• The appeals process would be reformed. All three models contemplate the need for administrative, quasi-judicial and judicial review, the potential for greater access to appeals, and a richer accumulation of expertise by adjudicators. This would guide both the sector and those who administer this complex area of law.

• Confidentiality restrictions around the registration process would be eased.

• Any body mandated to oversee the sector should have sufficient resources and expertise to develop policy, educate and communicate.

• There would be greater effort to foster knowledge of the rules and ensure compliance with them, including institution of intermediate penalties.

We particularly want to stress the second-last point. It will (and has been) argued that many of the perceived failings of Revenue Canada’s Charities Division stemmed from a lack of resources which precluded it’s doing its job welJ.10 While we accept that it is normally easier to do well with more resources than with fewer resources, we believe that the current problems with Revenue Canada’s (CCRA’s) administration of the charity portfolio are not solely due to a lack of funding. They are, for the most part, structural, resulting from the conflicting roles of a tax collector and what can be described as an adjudicator without jurisdiction.

Having said that, we believe that there is no point in creating a Tribunal (or indeed adopting either of the other two options) if there is not going to be sufficient funding.

3. Finally, we would like to make some observations about The Charity

Commission for England and Wales.

The English Commission is a body which merits close examination by anybody who wants to import the concept of an independent decision maker into Canada. Its role in England and Wales would encompass what we have in Canada as the joint roles of Revenue Canada (CCRA) plus the provinces if they exercised their jurisdiction plus a kind of advisory, nurturing body of the type envisaged for the Agency concept in the Joint Tables Report. II

The Commission works extremely well within its contex2 but that context is not Canada. It is our view that we can learn much about how a Canadian version of the Commission should operate from studying the England and Wales model but at the same time we believe that it is both impossible and undesirable to try to replicate that model in Canada. We make frequent references to how the Commission operates in this article, not because we take those examples as determinative, but because we think they offer ideas and options which are useful in designing the Charity Tribunal.

Introduction and Background

The road which had led us to our belief that a Tribunal should replace the Charities Division has been a long one, and not as direct as some might suppose. From the early 1970s until the mid-to-late 1980s, the working relationship of the charity community with the Charities Division was excellent. The Division was efficient, applications were handled expeditiously, and there seemed to be an attitude of co-operation between the Division and the sector. At a time when Revenue Canada was in bad odour (1983-84),13 many believed that the Charities Division was far and away the best-run and most respected in the Department.

However during the last part of the 1980s, there appeared to be a change in attitude at the Division which resulted in an increasing resort to the courts. This quickly revealed that the law governing “what is a charity” was more restrictive than most people had understood it to be.14 The rules as to what was “acceptable” behaviour for charities, most notably on the educational/advocacy/political continuum, developed in an extremely restrictive manner.

The cases won by charitable organizations were for the most part considered to be legal anomalies5 In more recent years there has been an increase in cases where there have been deregistrations, not just a refusal to register, based for the most part on a narrow reading of what is meant by the term “political activities”.16

For those working with, and arguing, the developing Canadian case law, it became apparent that England (presumably the source of the common law for the Canadian courts and Revenue Canada) was home to a more responsive approach to both definition and activities, i.e., one that recognized that charity is a living thing. This appeared to be so because since 1960, the decisions on most of the crucial areas were made primarily by the Charity Commission of England and Wales and not the British tax officials. The decisions of the Commission were seldom challenged, so that while the law in England was changing de facto, there was no reported body of court cases in which Canadian judges could find precedents7

It is probably fair to say that until the mid-1990s, there was little if any Canadian understanding of, or interest in, the concept of a charity commission. But after the string of courtroom losses and a backlog of decisions on hard cases, the difference between Canadian and English law became so striking that some began to think that the “answer” to the problem of a narrow definition of the term “charity” might lie in the creation of a Tribunal. 18

In 1995, the Department of Canadian Heritag9 commissioned Arthur Drache to produce a paper examining the possibility of importing the commission concept to Canada. This paper was subsequently published,20 thus putting the idea into intellectual play within the voluntary sector.

The core of the concept of a Canadian Charity Tribunal is that it would be in a position to interpret the common law (as does the English Commission) and any legislative initiatives from an independent perspective, rather than from within a framework that gives priority to the collection of taxes.

The process leading to this current call for a tribunal was accelerated in 1999. The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in the Vancouver Society of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women21offered the most meagre gruel for those who had hoped for a judicial expansion of the definition of charity. To make matters worse, the Court clearly put the ball back in the court of the legislature, refusing (after some very kind comments) to impose a newly suggested approach argued for by the Canadian Centre For Philanthropy, an intervenor. The Court as a possible source of reform had opted out.

The Broadbent Report, which had been withheld pending the decision of the Supreme Court in the Vancouver Immigrant Women case, was published the following month. It was a wide-ranging paper which stimulated discussions, not the least of which revolved around its version of the English Charity

Commission. In our view the paper suffers from real problems in identifying jurisdictional boundaries and in having what we believe to be a naive approach to what could be achieved through institutional changes at Revenue Canada (CCRA).22 As noted in the Foreword to this article, it appears that the Broadbent Report’s suggestion of an “Agency” as a buffer between the government and the sector is ill-conceived.23

The creation of the Joint Tables group comprised of both senior government and sector representatives attests, we believe, to the fact that all sides realize that the status quo is unacceptable and that the traditional way of resolving the legal issues is not working and will not work. It is our belief that the fact that the Commission concept was unanimously embraced by the voluntary sector representatives of the Tables while the civil servants remained neutral amongst the three options simply shows that the sector people have been living with the issues and problems for a much longer time than have the bureaucrats.

With this background to the genesis of the Tribunal idea, we now turn to an examination of the reasons why as a generality, the tax authorities should not be the people to make decisions about whether an organization does or does not qualify for tax concessions based on its status as a charity.

In many countries around the world, the tax authority is the decision maker for determining the sorts of organizations which are recognized as “charitable” (or as public benefit organizations or whatever term is used in the particular country) for tax purposes. And while the scope of tax benefits may vary from country to country, the fundamental question- whether it is appropriate for tax officials to make what amounts to fundamental social policy decisions —is being questioned.

International Experience

The issue has arisen in such diverse countries as New Zealand, Scotland,24

Singapore, South Africa25 and in many European nations, both east and west. While the issue is framed in different ways, a common consideration is the desirability of a “charity commission”. While many countries look to the Charity Commission of England and Wales as a model, many others have doubts about adopting this specific approach. All approaches have in common the basic premise that the tax authorities are not the proper ones to decide on policy matters relating to charitable status.

An interesting confirmation of the concept of a charity commission was its broad endorsement (much to the surprise of many participants), at a conference held in May, 1999 in Budapest. It emerged from a workshop held under the sponsorship of the International Center For Not-For-Profit Law, which brought together a small ( 60) group of lawyers and bureaucrats from across Europe who were involved with nonprofits.

The conference was entitled European Civil Society in the 2Jst Century: Standards and Mechanisms for Regulating “Public Benefit” Organizations.26

One of the four working groups at the conference discussed “Appropriate Decision Makers”. There were intensive meetings which ran for two full days with representatives from 11 coul)tries, most of them east European but including one each from Italy, Germany and England.

There were four basic approaches identified which are used to determine which organizations are recognized as being “charities” or public benefit organizations. These are the courts (Hungary), the tax authorities (several), a charity commission (England and perhaps in the near future, Poland), and other (non-tax) government departments. Initially, it was apparent that representatives from each country thought their system was the ideal.

The participants then used a sort of matrix (not unlike that used in the final Report of the Joint Tables), setting out the characteristics of an ideal system. These included fairness, speed, cost, consistency, absence of political interference, societal values and appeal options, as some of the key considerations. Each of the four basic approaches was rated on these characteristics using a discussion/voting approach. To the surprise of many, the upshot was that the concept of a charity commission came out far ahead.

Obviously, the conclusions did not take into account the political realities in each country but this arguably made them more valuable, given that a consensus emerged amongst experts about the “ideal”, even if that ideal might be a nonstarter in their own countries.

Some countries (as diverse as Barbados and Hungary), have taken a part of that jurisdiction away through legislating more precise definitions in various statutes. These moves are designed to at least partially limit decision-making by tax authorities. This approach was recommended by the final Joint Tables Report27 though it is presented in a fashion which does not specifically state that the need for such legislation stems directly from the failings of Revenue Canada and the courts as social policy decision makers.

Why The Tax Authority is Not Appropriate

We now turn to a general discussion of why the tax authority is not generally the appropriate decision-maker, as a matter of social policy, to determine what types of organization should receive tax benefits.

1. Tax authorities are trained to raise taxes. The culture in which they work has an innate bias which leads employees to try to maximize tax revenue. Giving them the authority to accept or reject an application that may produce significant tax revenue loss puts them in a conflict situation. The 1999 decision of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, Blair Longley v. M.N.R., demonstrates the problem.28 One of the contributing factors in the Longley decision was the secrecy surrounding the work done within Revenue Canada.29

2. A second element relates to the role of tax authorities in enforcing compliance. While tax authorities put out huge amounts of information to the public and spend millions of dollars on communication, the thrust of their efforts is to promote compliance with the Jaw. You don’t go to the tax authorities for advice about how to reduce tax liabilities or for their approval of tax reduction ideas.

This is equally the case for the Charities Division. It is extremely helpful in advising charities and nonprofits about compliance, clearly one of the Division’s functions. But this should not be confused with any sort of “nurturing” role. Both the Broadbent Report and the Joint Tables Report, to a Jesser extent, foresee a new body which “helps” or “advises” charities, presumably to meet their charitable goals and to assist them to operate in an efficient manner. This is not a function which can or should be given to a division of a department whose role is to collect tax efficiently and promote compliance.

3. Most officials in tax authorities have no formal training or background geared to the decision making necessary to determine the legal status of a charity.30 Individuals may be lawyers, accountants or have related professional or educational qualifications. There is no requirement that they have any specific educational or occupational background when they join the Charities Section. Individuals are not social policy makers nor are they trained to make social policy. The corporate culture in which they operate makes it easier for them to say “no” rather than “yes”.31 In a milieu where success is measured in part by increasing the efficiency of tax collection and maximizing that function, it is to be expected that exemptions from tax will be granted reluctantly.32

4. In most countries, the tax authorities are administrators and do not write the tax codes. In Canada, Finance writes the Jaw and Revenue Canada (CCRA) administers it. This raises a number of problems because the policy makers are not the administrators. There have been instances in the recent past where substantial tax changes relating to charities have been put in place by Finance without informing Revenue. Conversely, there is evidence that Revenue has often requested tax changes which Finance refuses to countenance.33

Simplifying administration is important to tax authorities, and the fewer exceptions there are to the general tax regime, the better.34

In the hierarchy of government, Finance is the dominant department and Revenue is subservient insofar as policy making is concerned.

Charity issues are a minute aspect of the interrelationship. Many believe that giving rt<sponsibility for charity administration to a new body which wiii be pre-eminent at the federal level and which would have direct access to Parliament would result in better and more expeditious tax legislation than is currently the case.

5. Tax departments are large bureaucracies, with people moving from division to division with regularity. As an atypical part of a large department, Charities Division can offer few opportunities for career advancement. As a result, few remain long enough to develop expertise, a fact which significantly affects the quality of decision making.

6. Most tax administrations, quite properly, operate on a system of extreme confidentiality about tax information. This imbues departmental employees with a secretive approach to their work. In our view, this is inappropriate in the context of dealing with many issues relating to charities.35 Unfortunately, this approach often carries over to such matters as guidelines to registration as nonprofits, administrative issues, and an unwillingness to discuss publicly issues which are of concern to the Department and to the community.

This issue was recognized by the government two years ago when there was some loosening of the confidentiality rules to allow some very limited public access to information.36 The Joint Tables Report also recommends a series of possible steps to try to make the workings of the Charity Section more open. This is one of the changes the Report contemplates when it talks about an “Enhanced Revenue Canada Charities Division”.37

The question which has to be posed is whether it is feasible to try to create an “open culture” for one very small section of Revenue Canada (CCRA), while at the same time maintaining the necessary requirements of secrecy and confidentiality for all other parts. The simpler, and more efficient approach, is to put the decision making into a new body which is not bound by Income Tax Act notions of confidentiality but which has a specific statutory mandate to be open in its operations.38

7. Lastly, there is the issue of appeals. When tax cases go to court, in almost every jurisdiction (including Canada) the onus is on the taxpayer to show that the tax authorities are wrong in their assessment. The courts start with an institutional bias against the appellant. While not a question of guilt, the onus often operates with that tenor and the applicant is presumed to be guilty until proven innocent.39

The problem of appeals is exacerbated by the fact that the process is an appe40 to the Federal Court of Appeal. Not only is the onus of proof on the charity or organization in question, but the basic rules applicable in the Tax Court of Canada, such as the right to have examinations for discovery, call witnesses, and cross-examine the government’s decision makers, do not apply.

In the Joint Tables Report,41 the problem of “appeals” is noted as an issue to be put forward for consultation. In fact, of all the problems inherent in having the tax authority making decisions about charitable status, this problem could be most easily solved. We could return to a situation we had before 1972 where the appeals go to a lower court, which would not only make the process more accessible but would also make it fairer. A statutory amendment could resolve the “onus” issue.

The appeal issue can also be looked at in a completely new context if, in fact, a Tribunal replaces Revenue Canada (CCRA) as the arbiter of charitable status at the federal level.

A General Point About The Delay In Processing Applications

We must now discuss a significant problem which is not necessarily related to decision-making authority.42

A problem faced by all those who make applications for charitable registered status with the Charities Division is the length of time it takes to have an application processed. We are not referring to the occasional contentious application which may take years to settle, but the time it takes to handle the typical application, as well as other routine matters.

Sossin states that: “[t]he process typically takes between 7 and 15 months”, an observation which would probably be confirmed by most practitioners in Canada who have experience with such applications.43 The problem is not just one of the obvious difficulties created for organizations which, for the most part, are operational during the application process. Under the Income Tax Act,44an application is deemed to have been refused if the Minister has not given the applicant notification of its disposition 180 days after the application was filed. In fact, if it were not for applicants’ patience, Revenue Canada’s (CCRA’s) administrative policies, and the prohibitive cost of appealing a deemed refusal to register, the system as legislated would collapse into chaos.

By way of comparison, in the 1998 Annual Report of The Charity Commission of England and Wales, issued in mid-1999, we find the following statement:

During 1998 we responded to 93% of registration applications within 15 working days, and 94% of other correspondence within 20 working days.

Other countries may have worse records than Canada4S but it is crucial that those who are not regular users of the system be aware of just how slow it is, and also be aware that the problem has been getting worse, not better. A decade or 15 years ago, the normal wait would be measured in weeks, not months. No matter what the ultimate decision may be on the question of which body makes the registration decision, it is absolutely crucial that the process be made reasonably expeditious.46

The Role of The Tribunal

Before we consider how the proposed Tribunal should be structured, it is important to determine what its role should be. As any architect will attest, “form follows function” and unless we have a clear idea of what the Tribunal should do, we cannot comfortably discuss how it should be organized.

There were two models put forward in 1999. The first, contained in the Broadbent Report47 was summarized as follows:

• Provide voluntary organizations with support, information, and advice about best practices related to improving accountability and governance;

Collect and provide information to the public;

• Evaluate and make recommendations regarding registration of new applicants; and

• Assist organizations to maintain compliance with Revenue Canada (CCRA) and other regulatory requirements and investigate public complaints.

The most striking aspect of this suggested role is that it gives no real power to the Commission which acts only in a advisory role to the Charity Division which keeps all the legal powers involved in registration and deregistration. While some have suggested that the recommendations of this body would carry significant weight with Revenue Canada (CCRA), in practice this is unlikely to be true because the Charities Division will always take the position that it must follow “the common law” and “the courts” and cannot allow the Agency’s recommendations to take precedence.48

Equally of concern to many organizations is the fact that the Broadbent proposal would create another layer of bureaucracy and cost without appreciably improving the system.

The Report of the Joint Tables, in discussing a Commission as one of three options, sees its role as:

A quasi-judicial commission would undertake most of the functions currently carried out by the Charities Division. It would provide authoritative advice to the voluntary sector, and expert adjudication of appeals on decisions by its Registrar. At the same time, such a commission would have a support function not unlike model B’s agency.49

After considerable reflection, we have come to the conclusion that in the first instance, the role of the Tribunal should be even narrower than that set out in the Joint Tables Report. We take the position that it should, at the start simply take over the current Revenue Canada (CCRA) role of registration and deregistration.SO We consider that, as desirable as many of the other roles may be, the effort involved in the shift of responsibilities and the development of new policies will be so demanding that no additional roles should be contemplated in the near term.

The question is not whether there should be a Tribunal, but among the many things that need to be done after it is established, what should have priority. The Joint Tables Report has a number of recommendations. At this stage, it is not clear which (if any) will be accepted and in what form.

For example, if the proposal legislatively to expand the list of organizations which are given “quasi charitable status”51 is accepted, one of the first tasks of the Tribunal will be to develop criteria for identifying qualifying organizations. Similarly, if the Joint Tables Report suggestions about the introduction of “intermediate sanctions” is accepted,52 substantial work will have to be done to develop guidelines, not to mention work on an appeal process.

If the Joint Tables Report’s view that new approaches are needed to deal with issues such as “advocacy” and “related business” is accepted, the Tribunal will have to develop rules and guidelines, whether or not there is a new legislative framework.

Of course, if one of the overall purposes of the creation of a Tribunal is to look at the whole issue of registration with fresh eyes, it will be incumbent on that body to review all of the Charity Division’s current interpretations and, where necessary, make changes.

Given that one of the purposes of a shift from the Charities Division is to have a more open approach, a high priority will have to be given to the rewriting of the public documents currently used by Revenue Canada, the developing of new ones, the development of more open procedures, and taking steps to increase accessibility to the system.

There will also have to be significant attention paid to the issue of an appeal system, not just in the context of the “intermediate sanction” proposals but also vis a vis refusals to register and deregistrations. There is a consensus that the current appeal system which starts at the Federal Court of Appeal cannot continue.53 But there is considerable work which must be done to develop an alternative and this work has to be done within the context of a shift from Revenue Canada (CCRA) control of the system to a Tribunal.

A couple of points should be made about the continuing role of Revenue

Canada (CCRA). It is our view that the audit function of charities should remain with Revenue Canada (CCRA) which continues to have the role of administering compliance with all aspects of the tax law.54 We think that it only makes common sense that Revenue should continue to effectively supervise the whole area of the tax treatment of charitable gifts as part of its assessing practices and, given the interrelationship of gifting and organizations, it would make little sense to say that the same department cannot look at the donee side of the equation as well as the donor side.

As will be suggested in Part II of this article, the audit side of Revenue would report to the Tribunal any problems which it finds but it would be up to the Tribunal to take the appropriate steps, whether “intermediate sanctions” or deregistration. When we discuss the issue of appeals, we will look at the role and status of Revenue Canada (CCRA) as well as operational issues.

Conclusions about a Tribunal

The Tribunal will have considerable work on its plate in the first few years of operation, a burden which may or may not be increased by legislative initiatives as recommended by the Broadbent Report and the Joint Tables Report. We think it is unrealistic at the start to expect it to play any of the other roles which have been suggested for it. However, with the passage of time and the development of a smooth internal operation to deal with the primary matters under its jurisdiction, we would expect that its role would expand.

We would also expect that, from the beginning, the Tribunal would play an informal role in transmitting sectoral concerns to government (through annual reports) as well as governmental concerns to the sector. Similarly, we would expect that fairly early on, steps would be taken to make contact with provincial authorities to see what level of co-operation might be developed.

We stress that the final design of the Tribunal will depend to some extent on what changes, if any, are made to the Income Tax Act. While we think there is a need for a Tribunal, whether we have the legislative status quo or legislative change, the nature of changes should have an impact on the design of the Tribunal and the people who are chosen to implement its policies.

FOOTNOTES

I. Author’s Note: Funding for this project was provided by the Non-Profit Sector Research Initiative, established by the Kahanoff Foundation to promote research and scholarship on nonprofit sector issues and to broaden the formal body of knowledge on the nonprofit sector. The views and interpretations expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not represent any position or policy of the Kahanoff Foundation or the Non-Profit Sector Research Initiative.

The primary writer was Arthur Drache, though Laird Hunter did a first draft of some sections. There has been an intellectual collaboration between Arthur Drache and Laird Hunter over a period of many years and many of the ideas put forward in this paper are a result of that collaboration. In addition, Laird Hunter has read several of the drafts of the article and made extensive editorial contributions, not the least of which was the use of the term “Tribunal” as a substitute for the more commonly used “Commission”.

2. In this article, we continue to use the terms “Revenue Canada”, “the Department” and similar terms notwithstanding the fact that we are well aware that as of November I, 1999, Revenue Canada became the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (CCRA). Obviously, nobody really knows what changes, if any, may occur as a result of the new status of the tax authority in Canada but there has never been a hint of a suggestion that the Charities Division will operate any differently under the new corporate structure.

3. The Joint Tables Report is dated August 1999 but was issued in mid-September. It can be found on the Internet at www.pco.bcp.gc.ca/prog_e.htm or at www.web.net./vsr-trsb. It is a compilation of recommendations put together by three “Tables”, each of which was comprised of a number of senior federal bureaucrats and representatives of the charity community. It is expected to be the focus of an extended debate on the relationship between the federal government and the voluntary sector. [See, for example, Floyd and Wyatt (2000), 15 Philanthrop. No.3.]

4. Building on Strength: Improving Governance and Accountability in Canada’s Voluntary Sector, published in February 1999. It was produced by the Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector, chaired by Ed Broadbent and initiated by the Voluntary Sector Roundtable.

5. We have chosen the term Charity Tribunal to distance the consideration of this option of an independent decision-making body under the Income Tax Act from unnecessary comparisons- both in the positive and negative aspects- with the Charity Commission of England and Wales. The focus must be on the Canadian requirements for this function.

6. A report published by the Fraser Institute entitled Preserving Independence: Does the Canadian Voluntary Sector Need a Voluntary Sector Commission (Clemens and Francis, Apr1999) vociferously attacks the concept as set out in the Broadbent Report. Strangely, it relies to a great extent on a British Parliamentary Committee Report which was critical of the recent performance of the English and Wales Charity Commission. But at least insofar as the Joint Tables Report is concerned, the Broadbent suggestion stands in juxtaposition to the notion of a Commission, not as a replica.

7. Of course, Revenue Canada (CCRA) is not without its supporters. Vancouver lawyer, Blake Bromley in a paper delivered to the Pacific Business and Law Institute on May 20, 1999 entitled Table Talk: Dumbing-Down The Law of Charity in Canada comes to its defence.

8. Section 92 of the British North America Act states:

92. In each Province the Legislature may exclusively make Laws in relation to Matters coming within the Classes of Subjects next hereinafter enumerated; that is to say,

The Establishment, Maintenance, and Management of Hospitals, Asylums, Charities, and Eleemosynary Institutions in and for the Province, other than Marine Hospitals.

The subject is also discussed in the Report on the Law of Charities (1996) by the Ontario Law Reform Commission at page 5.

9. Ontario, through an active (some say overactive) Office of the Provincial Guardian and Trustee and Alberta in legislation relating to fundraising.

10. In a paper entitled Regulating Virtue: A Purposive Approach to the Administration of Charities in Canada delivered at a conference at the University of Toronto in January, 1999, Lome Sossin of Osgoode Hall Law School indicated that the Charities Division had 71 fulltime employees (FTE) in 1997 but was expected to have 133 in 1998. The data were contained in a letter to Sossin from Revenue Canada. (Hereinafter, this paper is referred to as “Sossin”. It will be published as part of a conference report.)

II. The former Chief Commissioner, Richard Fries, gave a speech in 1999 which outlined the current workings of the Commission. The speech was delivered in Budapest at a conference and is reproduced in full in Volume 2, Number I of the International Journal for Not-for-Profit Law at http://www.icnl.org/journal/v2issl/rfries.htm.

12. However, the Twenty-Eighth Report (1997-98) of the House of Commons Committee on Public Accounts entitled The Charity Commission Regulation and Support of Charities (The Stationery Office, London: 1998) is a tough-toned critique of the efficiency of the Commission. But, judging by the Commission’s statistical record, it remains, criticized or not, much more efficient in dealing with the public than is the Charity Division of Revenue Canada (CCRA).

13. During this period, the Department was subject to constant attack on every ground from its having “quotas” for auditors to its treatment of artists. In the 1983-84 period, virtually the entire senior bureaucracy was purged and comparative outsiders brought in. It was the flak surrounding the Department’s abusive behaviour which led to the “Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights”.

14. During this time we had such cases as Scarborough Community Legal Services (85 DTC 5102), Positive Action Against Pornography (88 DTC 6186), Toronto Volgograd Committee (88 DTC 6192), and Canada Uni, [1993] I CTC 48; (93 DTC 5001). Most of these, experts agree, would have been recognized as charitable in England but were not so recognized by the Canadian Federal Court of Appeal.

15. Most notable of these was Native Communications (86 DTC 6353), which could have been a seminal case but which the courts turned into an “Indian” case with limited application.

16. The first of these was the Briarpatch case (96 DTC 6294) F.C.A. Subsequently we had decisions in Human Life International (Canada), [1998] 3 F.C. 202 (C.A.), and Alliance For Life which severely narrowed the scope of a charity’s “political” activities.

17. The most striking example is that, by an international decision, the Charity Commission decided to recognize as charitable, organizations which had as their objects the improvement of race relations. Not only has Canada not followed suit but in the Supreme Court majority decision in Vancouver Society of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women, [1999] I S.C.R. 10; [1999] 2 C.T.C. I; 99 D.T.C. 5034, Iacobucci J. said:

As the matter is not in issue, I would decline to comment as to whether the elimination of prejudice and discrimination may be recognized as a charitable purpose.

That comment, in the context of a Canadian multicultural society, was probably a key element in convincing many that steps had to be taken to revisit the system as a whole because the courts were not going to offer any help or hope.

18. In our view, this “scope problem” is intimately linked to the time it takes to process applications, especially the hard cases. The Charities Division is part of the tax collection administration and has neither the mandate nor the institutional culture to enable it to allow the charities law to be responsive to the changing aims and operations of modem charities.

19. This Department had federal jurisdiction over “volunteerism”. In addition, many of its “client” groups found that they could not be registered as charities which in turn made fundraising difficult. This became a crucial issue at the time the paper was commissioned because of government funding cutbacks to the voluntary sector.

20. ‘The English Charity Commission Concept in the Canadian Context”, The Philanthropist, Volume 14, Number 1, p. 8. It is ironic that the author and those who commissioned the paper were looking at the concept of a Canadian Charity Commission as a method to bring about a more enlightened “definition” of what is charitable and a more generous approach to what are acceptable activities. In the end result, while the concept of a Commission remains very attractive, the definition problem seems to be a secondary purpose. There is a growing feeling that at least for Income Tax Act purposes, some sort of expanded listing of “acceptable” organizations should be legislated and some of the court-imposed limitations on activities should also be dealt with legislatively. This concept has been dealt with by Arthur Drache in a paper produced under the auspices of The Kahanoff Foundation entitled Charities, Public Benefit and the Canadian Income Tax System. The Joint Tables Report makes more limited recommendations regarding definition (suggesting legislating an additional six categories by way of Income Tax Act amendment as well as trying to offer a “solution” to the education/advocacy/political activity issue).

21. Supra, footnote 17.

22. The members of the Panel appeared to have a degree of trust in Revenue Canada officials and their goodwill which is not shared by many in the sector.

23. This is what we take to be the essence of the Fraser Institute’s objection to what the Broadbent Report calls the “Voluntary Commission”. In fact, the Fraser Report endorses the idea of an independent panel, armed with updated directions frop1 Parliament, the concept advanced here. (Supra, footnote 6 at pp.28 and 33.)

24. See ‘The Regulation of Charities in Scotland” by S.R. Moody, Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Dundee, published in issue Number 4 of the International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law accessible at http://www.icnl.org/journal/volliss4/index.html.

25. See The Ninth Interim Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Certain Aspects of the Tax Structure of South Africa (more commonly called the Katz Report) which can be found at http://www.icnl.orgljournal/voll iss3/index.html.

26. A whole issue of the International Journal of Not-For-Profit Law has been devoted to this conference. It can be found in Volume 2, Number 1 or at http://www.icnl.org/journaVv2iss1/index.html.

27. Page 52.

28. 1999 Carswell BC 1657. Blair Longley came up with a scheme under which people could make payments to a registered political party and then have the funds flow back for their personal benefit. He asked the tax authorities for an opinion on the scheme and was told that it was not legal. The case reports that there was an internal legal opinion that the scheme was legal, albeit exploiting a loophole in the drafting of the tax legislation.

In due course, Longley alleged that he had been misled by officials and brought action. In the end result, he was awarded damages for the “public misfeasance” by the Revenue Canada officials which included $50,000 as “punitive damages”. In our view this case demonstrates in part the problem of institutional bias against tax reductions.

29. One of the problems faced by charities which appeal Revenue Canada (CCRA) decisions is that they do not have the right to use the discovery process to depose revenue officials or call them as witnesses under oath so that the matter of personal bias or worse can almost never be brought out in a court proceeding. In noncharity cases, officials are routinely examined both through discovery and as witnesses in open court.

30. Sossin, supra, footnote 10, describes “on the job training” at page 17 of his paper.

31. In a conversation with an official from Inland Revenue in England who deals with the issue of charities and the tax system, the following point was made:In Scotland, which is not subject to the jurisdiction of the Charity Commission of England and Wales, Inland Revenue maintains an “index” of charities for tax purposes, making decisions based on the common law as to which organizations qualify. The official told us that the Inland Revenue officials in Scotland were unhappy with having this jurisdiction because they are not trained for it, and expressed hope that the review of the overall situation which is now underway in Scotland would result in Inland Revenue being stripped of what it views as an onerous obligation.

32. In a 1999 Press Release designed to counter some false information which appeared in the media, Revenue Canada provided this data:

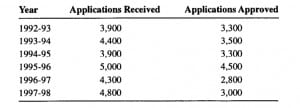

These figures show that in 1992-93, 84.6 per cent of applications were successful. In 1993-94, the rate of success dropped to 79.5 per cent. 1994-95, saw the rate back to 84.6 per cent, with the actual number of applications and registrations being identical to the 1992-93 figure, notwithstanding the fact that the Department often talked about the increasing volume of applications. 1995-96, we hit a highwater mark for applications—5,000-of which 90 per cent were accepted. Then we see the big change. In 1996-97, only 65 per cent of applications were accepted and in 1997-98 the percentage dropped to 62.5. These figures probably do not include applications which were abandoned without a formal application on the basis of initial negative reactions.

33. This was alluded to in Longley (supra, footnote 28), where Finance refused to take steps to eliminate the “loophole” which caused Revenue’s administrative angst.

34. This issue became very clear in the debates about exemptions which might be given when the Goods and Services Tax proposals were being debated.

35. For example, when there are public complaints about a charity, Revenue Canada is precluded from commenting on the particular charity and has to fall back on banal generalities. The English Charities Commission can, and does, speak out publicly about specific charities and often puts out press releases about them. It, of course is not bound by the same rules of confidentiality as are tax authorities.

36. The first such step was taken more than 20 years ago. It allowed the public access to the public information returns of charities pursuant to subsection 149.1(15). The most recent changes are contained in subsection 241(3.2) which states:

An official may provide to any person the following taxpayer information relating to a charity that at any time was a registered charity:

(a) a copy of the charity’s governing documents, including its statement of purpose;

(b) any information provided in prescribed form to the Minister by the charity on applying for registration under this Act;

(c) the names of the persons who at any time were the charity’s directors and the periods during which they were its directors;

(d) a copy of the notification of the charity’s registration, including any conditions and warnings; and

(e) if the registration of the charity has been revoked, a copy of any letter sent by or on behalf of the Minister to the charity relating to the grounds for the revocation.

37. Joint Tables Report, p. 49.

38. Realistically, no matter what sort of ultimate solution to the problem of jurisdiction is arrived at, there will remain some issues of confidentiality on specific files. The thrust of the policy for a new organization, however, should be that the public has a right to know unless there is an overriding public policy to the contrary. This, of course, is in sharp contrast to the status quo.

39. This applies to tax cases relating to charitable status as the Federal Court of Appeal recently confirmed in its decision in Human Life (International) of Canada (supra, footnote 16). Ironically, in common law jurisdictions at least, in nontax cases relating to charitable status, there is a presumption in favour of recognizing charitable status and intent.

40. In England, if someone wishes to challenge the decision of the Charity Commission, there is a trial de novo, not an appeal from the decision. This approach results in different procedural issues coming into play, including one of “onus”.

41. Page 63.

42. Part of the problem invariably does have to do with the jurisdictional incapacity on the part of the Charities Division. Some number of applications will raise novel or contentious matters for determination. That number cannot properly be considered by the Division. There is either no clear law to apply or matters of mixed fact and law which need to be determinatively resolved. Without a way to get a decision to administer, the Division has no recourse but to thoroughly consider the matter to try to make it fit or to deny the application. The result is long periods of waiting by applicants and an intolerable position for administrators.

43. Supra, footnote 10, p. 16. In a conversation with Arthur Drache, Sossin said he got the information from a senior official in the Charities Division.

44. Subsection 174(4).

45. We have been told that in India the process takes years unless it is hurried along with bribes. One Canadian lawyer remarked that if bribes were a feasible option to speed up the Canadian process he’d gladly pay them!

46. It should be observed that all this is taking place in an era where citizens as consumers expect (and for many things) receive instant service. Some provinces provide for corporate registrations over the Internet, a process measured in minutes. Even without that method, the time taken is a short number of days. Taxpayers can e-file and get refunds in days. Everywhere just-in-time service standards lead people to expect prompt, uncomplicated results. People motivated by altruistic notions of service are galled and distressed to find that an “approval to do good” can take months and then possibly be denied. This frustration factor cannot justify inappropriate measures but it needs to be clearly borne in mind when assessing the problem and examining the remedies.

47. Page 58, with a summary at page 89.

48. This view is bolstered by experience with the National Arts Service Organization initiative where the decisions as to qualifications are made by the Minister of Communications (now the Minister of Canadian Heritage) pursuant to subsection 149.1(6.4) of the Income Tax Act. Registration is to be by Revenue Canada. Very few such organizations have been registered since the inception of the concept in 1994, retroactive to 1990. Those involved in the field believe that Revenue Canada has applied its own standards to thwart the full implementation of the concept and that officials at Canadian Heritage now “self-censor” applications because of problems they know Revenue will create for applications.

49. The term “model B” refers to the Agency approach put forward in the Broadbent Report.

50. Supra, footnote II.

51. Joint Tables Report, p. 52.

52. Ibid., p. 58.

53. See, for example, the comments of the Joint Tables Report at page 55, one of the “shared assumptions” for all three models discussed in the Report.

54. We believe that an important precedent for much of what we are discussing here is the role of the Cultural Property Export Review Board. It has binding powers which have a direct financial impact on tax revenues and its role is recognized under the Income Tax Act. But through its relationship with Revenue Canada (CCRA), investigatory powers are de facto vested in Revenue Canada (CCRA) through its audit and assessment procedures. The interplay of the Board, Revenue Canada (CCRA), taxpayers, the courts and the various pieces of legislation which apply may be a partial model for the development of the new Tribunal and its various relationships. In Appendix C, we look at how the Cultural property Export Review Board works.

Appendix A Institutional Change

Given the objectives of the regulatory framework for the voluntary sector and the need to make changes therein, the Regulatory Table has developed three models for the institutional or regulatory oversight arrangements:

Model A: an enhanced Revenue Canada (CCRA) Charities Division.

Model B: an agency, somewhat similar to that proposed by the Broadbent Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector.

Model C: a commission, similar to the Charity Commission for England and Wales.

Below is an outline, in broad terms, of the models’ core mandates. The current vision is that each would be a federal body. There is potential, however, to design structures in a way that would allow opting-in or some other type of co-ordination with provincial authorities.

Model A: Enhanced Revenue Canada (CCRA) Charities Division

The Revenue Canada (CCRA) Charities Division would retain its current authority for the administration of the Income Tax Act with respect to charities. The Division’s mandate, however, would be expanded to include responsibility for facilitating public access to information about charities, and responsibility to assist charities with registration and compliance with the law.

The Division would be assisted by a committee, composed of individuals knowledgeable about charities and the law, that would advise on all aspects of the Division’s expanded mandate.ln addition, charities would be able to request an administrative review within Revenue Canada (CCRA) of Charities Division decisions.

Model B: Agency

The agency’s functions would complement those of the Charities Division. While the Divison would still make the decisions, the agency would, at greater arm’s length than the advisory committee of model A, make recommendations on difficult cases, issue policy advice, and help organizations to comply with the regulator.

As well, the agency would nurture and support charities and other voluntary organizations, and provide information to the public. This complements the option, outlined by the Table on Building a New Relationship, for an agency to nurture the relationship between the federal government and the voluntary sector.

Model C: Conunission

A quasi-judicial commission would undertake most of the functions currently carried out by the Charities Division. It would provide authoritative advice to the voluntary sector and expert adjudication of appeals on decisions by its Registrar. At the same time, such a commission would have a support function not unlike Model B’s agency.

The Models’ Shared Assumptions

The Table assumes that the following conditions would apply to all models:

• The appeals process would be reformed. All three models contemplate the need for administrative, quasi-judicial and judicial review, the potential for greater access to appeals, and a richer accumulation of expertise by adjudicators. This would guide both the sector and those who administer this complex area of law.

Confidentiality restrictions around the registration process would be eased.

Any body mandated to oversee the sector should have sufficient resources and expertise to develop policy, educate and communicate.

• There would be greater effort to foster knowledge of the rules and ensure compliance with them, including institution of intermediate penalties.

Self-Regulation in the Models

As a partial response to the need for change, self-regulation can be seen as having great merit. This is provided that no duplication of reporting requirements would be created if self-regulation became institutionalized.

The potential and effect of increased self-regulation are similar in each model.

Assessment of the Models

Each of the three models was assessed with respect to the identified need for change and with respect to a number of criteria:

the ability to improve the availability of public information and knowledge about the sector;

the potential for serving the non-charities part of the sector;

the ability to accommodate provincial involvement;

the compatibility of a support or nurturing function with other functions of the organization;

the effect on regulatory burden;

the degree of independence each would have from the government and the sector; the ability to enhance the confidence and trust of the sector and public; and government control of costs.

Chart I is a comparison of the models according to the preceding criteria.

Chart I—Assessment of the Models

|

Goals/criteria |

Vt: an Enhanced CD |

B: an Agency |

C: a Commission |

|

Improved public information and knowledge about the sector. |

Website and other measures could make for improvement over the status quo. |

Could be more vigorous program than under A. |

Same as B. |

|

Potential for serving the noncharitable voluntary sector. |

Status quo. |

Yes, on a voluntary basis. The Agency would be a more acceptable interface than CCRA’s CD. |

Yes, in that there are statutory obligations, and otherwise on a voluntary basis. The Commission would be a more acceptable interface than CCRA. |

|

Ability to accommodate provincial involvement, including, potentially, co-ordinated regulation. |

Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (CCRA) has a Board with provincial representatives. |

Broader potential for provincial involvement on a partnership basis. |

Structures could be developed to accommodate provincial input more focussed on the charitable/voluntary sector. |

|

Compatibility with a support or nurturing function. |

In the final analysis, CCRA will remain the “cop.” |

An Agency would provide significant scope for this. |

Regulatory and support functions can live side by side but the nurturing function is likely to be somewhat more restrained than under B. |

|

Regulatory burden: – compliance cost – efficiency/ duplication |

No change from the status quo (but some suggestions on short- form reporting). |

Burden could be lightened as a result of preventive regulation functions and assistance to individual groups on applications or with returns. |

Functioning of the Commission would need to be carefully designed to ensure there is no increase in regulatory burden. |

|

Degree of independence from government and the sector – including clarity of roles. |

Same as now, except for profile of the advisory committee. |

The Agency would be a friend of the sector. It would also have extensive working relationships with CCRA. |

A Commission would have greater independence from both government and the sector than would exist with either A or B. |

|

Enhancing sector confidence and trust in the regulator, e.g.: – working relationship – respect for confidentiality – objectivity of the appeals. |

Better working relationship than currently exists. |

Better working relationship than under A- to the extent that the Agency succeeds in its role of representing the interests of the sector. |

May be better than both A and B (good working relationship, objective and confidential advice, independent appeal machinery). |

|

Enhancing the public’s confidence and trust. |

Better than at present. |

Role may be difficult for the general public to understand. |

Same as A. |

|

Government control of costs. |

Government remains in control. |

Government retains control but the Agency, through its recommendations on (de)registration and through its policy advice, would still be in a position to push at the edges. |

Within the four corners of common law and statutory definitions, the Commission might see room for both narrower and wider interpretations, possibly resulting in a net gradual expansion of eligibility. |

General Comments Related to Chart I

• Assumptions on reform of the appeal process, the easing of confidentiality restrictions and greater compliance support already implied that all models would see improved transparency around registration, more effort to ensure compliance (including institution of intermediate sanctions), and a more accessible appeal process. Hearings on controversial cases could be instituted under any model.

• Compared with the current situation, all of the models would foster, to some extent, both the enabling and accountability objectives of the regulatory framework.

• On several other criteria (improved public information and knowledge, enhanced confidence and trust by the sector), the differences between models are incremental, with model C perhaps best situated to ensure public confidence. All models meet these criteria in varying degrees.

• The ability to accommodate provincial interests would be different under each model but it is not immediately clear which model would work best.

• The potential for serving the noncharitable voluntary sector is probably greater in models B and C. The agency in model B would perhaps have the greatest freedom to build partnerships and nurture the sector. The model C Commission would likely have the greatest independence from both the government and the sector and might therefore be able to integrate the compliance and nurturing functions most completely.

While the Regulatory Table did not seek a full consensus on a preferred model, there was widespread support among voluntary sector members of the Table for moving regulatory oversight out of CCRA. The Table saw greater merit in having integrated oversight rather than bifurcated responsibilities. The nurturing role that an agency could play, and the opportunities it could offer to enter into partnerships with other stakeholders, was seen as attractive. On balance, voluntary sector members of the Table favoured Model C, while government members tended to conclude that any model could work.

The Table did not pursue extensively the question of regulation of noncharities. The Table believes, however, that under any model, the oversight of “deemed charities” should be identical to, and integrated with, that of registered charities.

Several other issues concerning change to the institutional framework could be further explored. These issues include regulation of the wide spectrum of not-for-profit organizations discussed previously and governance issues such as the appointment and composition of a new oversight or advisory body.

Appendix B

Two Statutory Board Models From Federal Legislation

1. Standards Council of Canada

COUNCIL ESTABLISHED

3. A corporation is hereby established, to be known as the Standards Council of Canada, consisting of the following members:

(a) a person employed in the public service of Canada to represent the Government of

Canada;

(b) the Chairperson and Vice-Chairperson of the Provincial-Territorial Advisory Committee established under subsection 20(1);

(c) the Chairperson of the Standards Development Organizations Advisory Committee established under subsection 21(1); and

(d) not more than eleven other persons to represent the private sector, including non-gov- ernmental organizations.

Appointment of members of Council

6. (1) Each member of the Council, other than the persons referred to in paragraphs 3(b) and (c), shall be appointed by the Governor in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister, to hold office during pleasure for such term not exceeding three years as will ensure, as far as possible, the expiration in any one year of the terms of office of not more than one half of the members.

Requirements

(2) The members of the Council referred to in paragraph 3(d) must be representative of a broad spectrum of interests in the private sector and have the knowledge or experience necessary to assist the Council in the fulfilment of its mandate.

No right to vote

(3) The member of the Council referred to in paragraph 3(c) is a non-voting member of the

Council.

R.S., 1985, c. S-16, s. 6; R.S., 1985, c. 1 (4th Supp.), s. 33; 1996, c. 24, s.S.

Designation of Chairperson and Vice-Chairperson

7. (1) A Chairperson of the Council and a Vice-Chairperson of the Council shall each be designated by the Governor in Council from among the members of the Council to hold office during pleasure for such term as the Governor in Council considers appropriate.

2. Cultural Property Export and Import Act

Review Board established

18. (I) There is hereby established a board to be known as the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board, consisting of a Chairperson and not more than nine other members appointed by the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the Minister.

Members

(2) The Chairperson and one other member shall be chosen generally from among residents of Canada, and up to four other members shall be chosen from among residents of Canada who are or have been officers, members or employees of art galleries, museums, archives, libraries or other similar institutions in Canada; and up to four other members shall be chosen from among residents of Canada who are or have been dealers in or collectors of art, antiques or other objects that form part of the national heritage.

Acting Chairperson

(3) The Review Board may authorize one of its members to act as Chairperson in the event of the absence or incapacity of the Chairperson or if the office of Chairperson is vacant.

Quorum

(4) Three members, at least one of whom is a person described in paragraph(2)(a) and one of whom is a person described in paragraph (2)(b), constitute a quorum of the Review Board.

R.S., 1985, c. C-51, s. 18; 1995, c. 29, ss. 21, 22(E).

Remuneration

19. (I) Each member of the Review Board who is not an employee of, or an employee of an agent of, Her Majesty in right of Canada or a province shall be paid such salary or other amount by way of remuneration as may be fixed by the Governor in Council.

Expenses

(2) Each member of the Review Board is entitled, within such limits as may be established by the Treasury Board, to be paid reasonable travel and living expenses incurred while absent from his ordinary place of residence in connection with the work of the Review Board.

Appendix C The Cultural Property Review Board: Potential Precedent and Model

One of the generalized concerns which we have heard voiced over the past year or so when there has been a discussion of the possible implementation of a “charity commission” in Canada has been the issue of power over tax-related matters. Simply put, the question is whether an arm’s length body should make decisions which have a cost to the federal government in terms of reduced tax revenues?

It is worth keeping in mind that such a model already exists and that over the past 20 or more years, the government has not only not restricted its powers but has actually enhanced them, incorporating those powers within the Income Tax Act.

The Cultural Property Review Board, created under the Cultural Property Import and Export Act has extensive powers which can affect tax revenues of the federal and provincial governments.

The Board has the following powers:

o It can certify objects to be “cultural property” for Income Tax Act (and export) purposes.

o Cultural property which is donated or sold to a “designated institution” escapes capital gains tax completely.

o Gifted cultural property can reduce tax liability of a donor for up to I 00 per cent of annual income with a five-year carry forward of the excess.

o The Board can designate institutions which are eligible to receive such property.

o The Board certifies the value of such property and the assigned value is “deemed” to be fair market value under the Income Tax Act, and binding upon the donor and Revenue Canada (CCRA), though the donor has an appeal right. (This is a newish power given to the Board five or six years ago.) Revenue Canada (CCRA) can, however, challenge other aspects of the donation, such as whether it is a gift of capital property.

o The Board has funds available which it can give to an institution to allow it to purchase objects which are certified.

Aside and apart from certain extremely vague statutory guides, the Board sets its own rules with regard to determining what is cultural property and which institutions will be designated.

While the Board is appointed by the government, its nine members need not be (and usually do not include) government representatives. Rather, four are drawn from the institutional community (museums and galleries) while four come from the private sector—collectors, appraisers and dealers—as is required by statute. The Board has been, for the most part, free of political appointees and is well respected by all sectors.

The Board has worked closely with Revenue Canada (CCRA) on certain problems (such as “art flips”) and has created some rules to help the Department, while at the same time operating essential!y at arm’s length.

All costs, including administrative costs, remuneration for Board members and staff (who are public servants), support services and expenses are borne by the government. The Board issues an annual report which is a public document describing its work and discussing some of its more significant decisions. The Board has specific powers to hire experts and appraisers and the government underwrites the cost.

The point here is twofold:

First, the Board in effect “costs” the federal government tens of millions of dollars a year by certifying property for Income Tax Act purposes. This cost, of course, is in forgone tax revenue. It operates completely outside other government constraints including budgetary constraints based on deficit fighting. There is no limit on the number of objects the Board may certify in any given year.

Second, the Board is reflective of the two communities which are most interested in its work

-the institutional community which will get gifts and make purchases of cultural property and the collectors and gallery owners who usually have title to such items. Only once in its 25-year history has the Chair been a civil servant by profession and in this case, he had retired after a career which was primarily “culturally” oriented.

Thus, we have a model of an effective arm’s length body, funded by the federal government, which has a substantial role in making decisions which are income-tax related. In a broad sense, this would be akin to the role a charity commission might have under at least one of the options which is under consideration.

ARTHUR B.C. DRACHE

Drache, Burke-Robertson & Buckmayer, Barristers and Solicitors, Ottawa with

W. LAIRD HUNTER

Worten & Hunter, Barristers and Solicitors, Edmonton