by JAMES CUTT, CURTIS HANNIS, DENIS BRAGG, ARIF LALANI, VIC MURRAY AND BILL TASSIE

University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.

I. Introduction

It is business as usual in human service nonprofit organizations (HSNPOs) when demand for services increases much more rapidly than the resources needed to meet demand, and when managers and boards face a constant problem of allocating scarce resources internally, on the one hand, and competing for scarce public and voluntary dollars externally, on the other. Managers and boards should therefore have the answers to the following basic costing questions at their fingertips: What do administrative support services cost in your organization? How do you respond to the government’s proposal that you take over a new clinical program with a grant covering only the salaries of the clinical staff? How much does your prevention program cost compared to your treatment program? How does the cost of treating a client in your rural office compare with that of treating a client in your downtown location? Do you use program cost information in your budgeting process internally, and do you use this information in your funding requests to governments, charitable associations such as the United Way, and other donors? Could you respond to a request from a public auditor to demonstrate your efficiency in resource utilization compared to other nonprofit organizations and commercial alternatives?

As part of a broader research project on performance information across the management cycle-from planning and budgeting to evaluation and external audit-the researchers asked managers and board members in four HSNPOs in Victoria, British Columbia whether they had cost information, and if not, whether they would find it useful for making policy and management decisions. This paper demonstrates the development of a relatively simple cost accounting model for one of the four HSNPOs-Victoria Community Centre (VCC). (The name of the organization has been changed.)

II. Attitudes To Cost Information in HSNPOs

Without exception, managers and board members observed that their major preoccupation was living within very tight budgets, and that detailed financial information on actual line items of expenditure such as rent and salaries compared to budgeted information was available on a regular basis, often weekly, to managers and board treasurers, and at least monthly to all board members and often all staff, as the most common performance information.

Given this tight control over budget totals and line items of expenditure, managers and board members assumed that they therefore had detailed cost information, and that living daily within a budget meant that efficiency-getting the most from limited resources-was optimal. In fact, this detailed financial information is only the first step in determining the full cost of the various programs offered externally to clients or, indeed, of the various internal support programs (such as administration or building maintenance), and the average cost of units of service (such as the cost of a counselling visit). Information on full and unit costs requires a cost accounting system that includes specifying cost objectives, defining mission and support cost centres where information is accumulated, distinguishing direct and indirect costs for the group of cost centres, assigning indirect costs across centres, allocating the cost of support centres to mission centres, and using a process or job order system to arrive at the unit cost of outputs or activities. A basic cost accounting system using these components will be illustrated for vee.

As interesting as the assumption that they already had cost information was the reaction of managers and board members to the usefulness of actually having regular information on the total cost of programs serving clients and internal support programs, as well as the average cost of units of the various services provided. In general, managers and board members regarded such information as of low priority relative, say, to better information on client satisfaction or staff morale. Some board members also went further to observe that additional information on the costs of programs and units of output was unnecessary and even perhaps inappropriate in HSNPOs. The attitude of respondents to cost information clearly reflected, in part, some unfamiliarity with the specific nature of cost information, but the responses also reflected some other interesting perspectives on the concept of cost in HSNPOs.

Cost information was considered unnecessary because HSNPOs do not sell their products; since cost information is the first step to determining selling price, it is not necessary if no price is charged directly for the service. The only exception acknowledged by board and staff members was where HSNPOs receive all or part of their revenue based on a formal reimbursement formula; hospitals and nursing homes in both the U.S. and Canada therefore generally pay close attention to costs. With this exception, however, it is clear that the major incentives to discovering cost information and cost minimization in the commercial sector-appropriate pricing, competitive survival and profit maximization-do not apply in the HSNPO sector.

The question of appropriateness turned out to be more subtle. Two different explanations emerged: the first political, the second philosophical. It was pointed out that information such as the total and unit costs of different services (e.g., acute and preventive health services), or the cost of administrative support, might be very sensitive and possibly politically embarrassing, both within the organization and between the organization and its funders, by explicitly associating declared priorities and actual resource allocation. It was argued that it would often be awkward to reveal the difference between rhetoric and reality, to show that the “money did not go where the mouth was”. Like the pricing argument, this political argument also has substance; there is no question that total and unit cost information demonstrate actual rather than rhetorical resource allocation priorities and might therefore be embarrassing if there is variance between rhetoric and reality.

The philosophical argument is closely related to the political. Cost information, it was argued, is actually inappropriate in HSNPOs since it connotes a philosophy of “coping” rather than “caring”, and amounts to placing a monetary value, quite inappropriately, on human services. This argument is ill-founded in one respect; cost information does not place a monetary value on the services provided, but merely demonstrates how resources have been used in providing the whole program or units of service. In another respect, however, the point is well taken. Cost information forces recognition of the nature of scarce resources and the consequences of choosing how to allocate them-if resources are used to provide one service, they are not available to provide another. This kind of information about “doing as well as possible with limited resources” may be unwelcome to human service deliverers who believe in doing good as long as there is good to be done.

If cost information is less important because services are not sold, and may also be politically and philosophically awkward, the question which clearly arises is whether managers and board members in HSNPOs should bother with anything beyond the traditional line items of expenditures and the continuing chore of staying within budget.

III. The Usefulness of Cost Information in HSNPOs

Although managers and board members in HSNPOs are not concerned about pricing and profit maximization, they are, or should be, vitally concerned about the question of efficiency-about delivering services (at the program level and at the unit-of-service level) at least cost. This information is a key component of both internal and external accountability across the management cycle.

The key is to discover how to make best use of scarce resources. Internally, managers and board members need cost information in the first instance at the planning or policy formulation stage to make strategic choices-to determine the least cost way (by program and by units of service) of pursuing organizational objectives both through programs which provide direct services to clients and internal support programs (such as administrative services). Such information at the “front end” also makes possible the matching of actual priorities and resource allocation decisions manifested in budgetary decisions with financial resources and staffing. Cost information on what the organization is trying to do also serves as a benchmark by which the organization can determine on a continuing basis how it is doing with respect to the use of resources and, retrospectively, how it has done, and makes possible adjustments in the light of variances.

Externally, the same accountability argument holds. At the front end, external funding proposals on organizational plans and budgets are likely to be much stronger and more persuasive if they contain careful costing of proposed programs and demonstrate internal management systems to monitor efficiency. Funders are likely to require periodic reports over the cycle of funding, and more formal and comprehensive performance reports at the end of each cycle. Such reports, like those at the funding application stage, will be much more effective if sustained by costing information.

The case for internal and external accountability across the management cycle also puts the political argument against cost information in context. It is generally in the interests of all users of performance information-including external funders, evaluators and clients, and internal board and staff members-that performance information be valid, i.e., that it represent accurately what it is supposed to represent. Traditional line-item financial information simply does not provide a valid representation of resource allocation priorities, and occasional possible irritation on the part of one user, say, a board finance chairman, is a small price to pay for narrowing the gap between rhetoric and reality for other users. The philosophical argument provides an important reminder that the nature and use of cost information should be carefully explained to users, particularly staff and clients. But its extreme variant-that cost information is somehow improper and insensitive-simply reflects a misunderstanding of the concept of cost. Given the reality of scarce resources and the inevitability of choice, careful cost planning and monitoring help to ensure that resources are used to best effect in the pursuit of organizational goals. If resources are squandered in a costly or ineffective service, they are not available for other services. In short, knowing how well the organization is doing in allocating its scarce resources makes it possible for the organization to do as much good as possible. As usual, doing well and doing good are complementary rather than in conflict.

The argument then, is that cost information is useful, interesting, and appropriate-maybe in tough times, essential-so board members, staff and other constituencies in HSNPOs can have an “approximately right” sense about such information as the following: the relative costs of their support activities (such as administration); the relative costs of their frontline services delivered to clients; and the costs of specific outputs (either in average terms, say, the average cost of a counselling visit versus that of a clinical visit, or the specific, perhaps reimbursable, cost of a package of services delivered to a particular client). The question is whether it is possible to go quite simply from basic line-item expenditure data to such information: if the necessary procedure is very complex or perhaps conceptually rather contrived, it may not be worth taking this extra step. The next section attempts to demonstrate (for a HSNPO in Victoria, British Columbia), that the steps are simple and defensible-that indeed they simply try to formalize what managers perceive intuitively in any event. The final section of the paper will draw some conclusions on the use and attainability of cost information.

IV. Costing in the Victoria Community Centre (VCC)

The Organization

The Victoria Community Centre (VCC) is a nonprofit agency dedicated to fostering the growth, development and wellbeing of individuals, groups and the community as a whole. The primary funding sources for its $459,000 budget are the federal, provincial and municipal levels of government, the United Way, gaming revenue (from bingo and casinos), memberships, donations, course fees, and special events. vee services the communities of

Victoria, Saanich (Central and West), and Oak Bay, with its main clients being single parent, low-income families primarily headed by women and often receiving social assistance.

The mandate of VCC is to provide a friendly, supportive environment that encourages families and individuals by providing opportunities for community leadership and skill development. To carry out this mandate, VCC offers such services as counselling, peer support, services to young children, a drop-in centre for parents and children, life skills instruction and employment preparation programs. VCC’s fiscal year runs from September 1 to August 31 and the data analyzed are from September 1, 1991 to August 31, 1992.

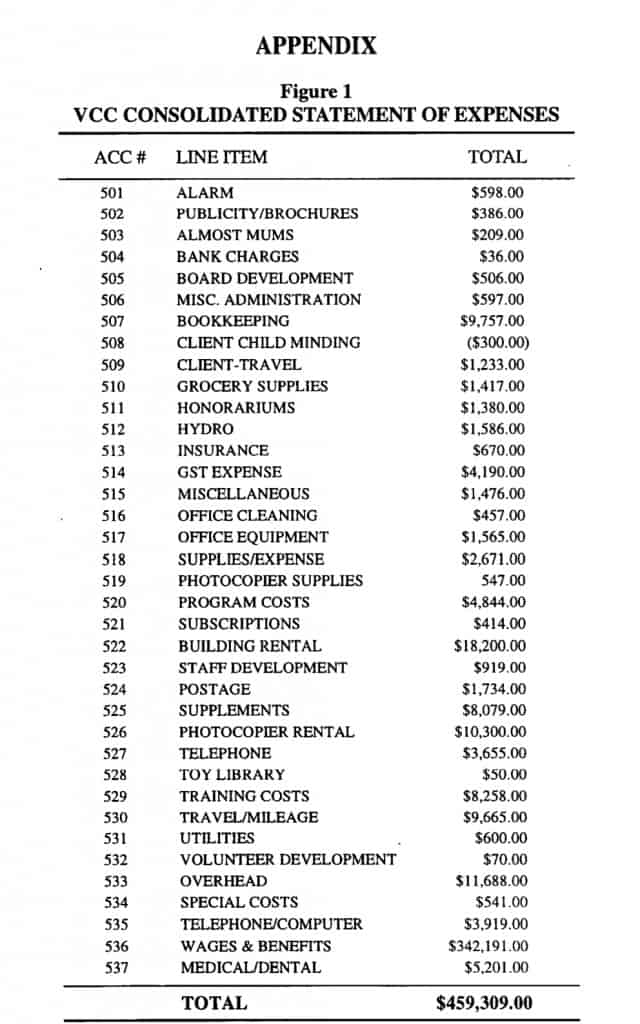

The first step in developing cost accounting for the VCC was to consolidate similar or duplicated items in its Statement of Expenses (Figure 1). This indicates that the largest category is wages and benefits ($342,191), followed distantly by such items as building rental ($18,200), overhead ($11,688), and photocopier rental ($10,300). (Figure 1, Appendix p. 21).

The Cost Model

Cost Objectives

In the next step of the model development, we obtained the agreement of the administrator and board of vee to provide information on the following cost objectives:

1) To determine those activities that could be classified as organizational overhead and calculate what proportion of total organizational cost could be attributed to them. The point here is to arrive at an overhead proportion that is better than arbitrary or “what the market will bear”, and further, to determine just what constitutes a defensible overhead proportion (in relation to similar organizations) in order to shed light on the consequences of slashing overhead activities in times of budgetary stringency and of accepting contracts that rule out any overhead support;

2) To go beyond an aggregating approach to overheads by determining what drives the use of overhead activities by client service programs (funding programs were excluded in the first instance), and then using that cost-driven information to load overhead costs down onto client service programs. In this way, the full cost-including an appropriate share of organizational overhead costs-of each of the client service programs could be determined. This information would make possible realistic negotiations with funders and program cost comparison with similar organizations. Further, this client service full-program cost information could be used in association with information on the number of clients (or a similar output measure) to determine unit cost-the average cost of a unit of service-and therefore, where necessary, what price to charge or reimbursement to request.

Identifying the Cost Centres

In the light of the cost objectives, cost centres are the organizational units in which appropriate cost information is to be accumulated. The usual division is into two categories: mission centres which deliver services directly to clients and support centres which support, i.e., deliver services internally to mission centre activities. The nature and number of overhead cost centres selected will reflect the cost objectives and the degree of detail needed in breaking down overhead costs as well as the need to keep the model as simple and workable as possible. The mission centres developed from VCC’s numerous program functions were:

Youth and Family Counselling (YFC) Peer Counselling (PEER)

Job Development (JOB DEY)

Community Kitchens (KITCH) Family Advancement Worker (FAW) Work Orientation Workshop (WOW) Healthy Babies Program (H-BABES) Nobody’s Perfect (NOBODY)

Safe Home (SAFE) Family Centre (F-CTR) Job Activities (JOBACT)

Support centres were categorized by function as follows: Central Administration (ADMIN)

Office-Related Expenses (OFFICE)

Building and Maintenance Charges (BLD/MA) Training and Development Costs (TR/DEV)

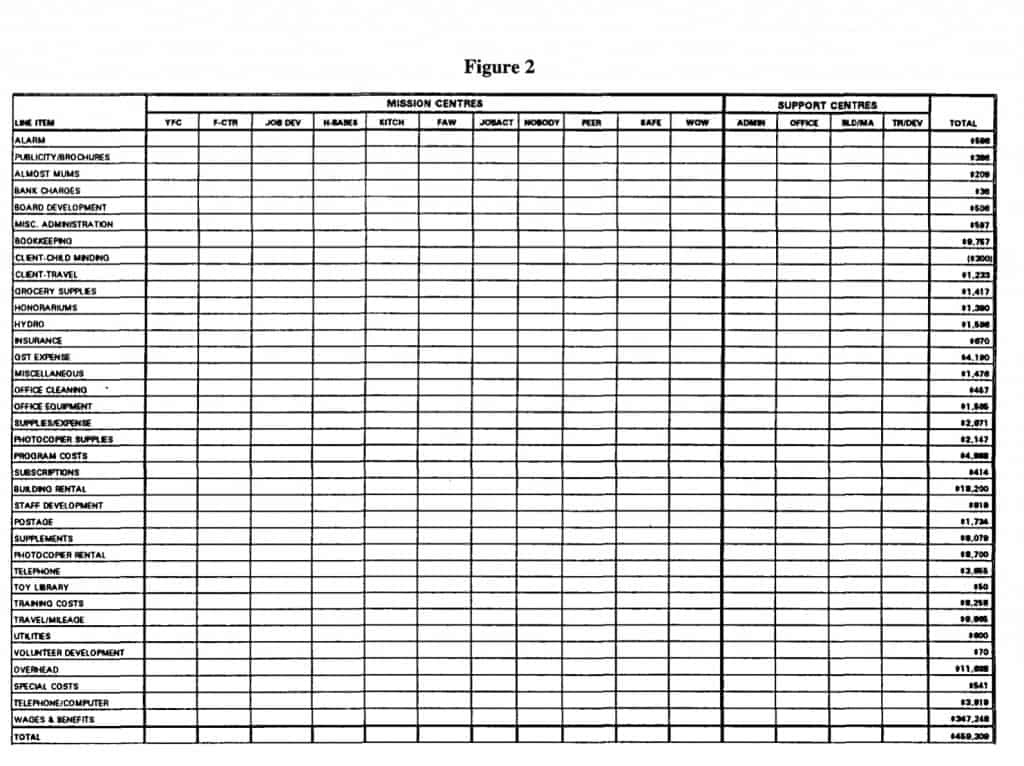

Figure 2 shows the line-items of expenditure and the set of mission and support centres; the task is to find some way of distributing the expenditure totals across the cost centres. The first part of this task was to make a decision about direct and indirect costs. (Figure 2, Appendix p. 22.)

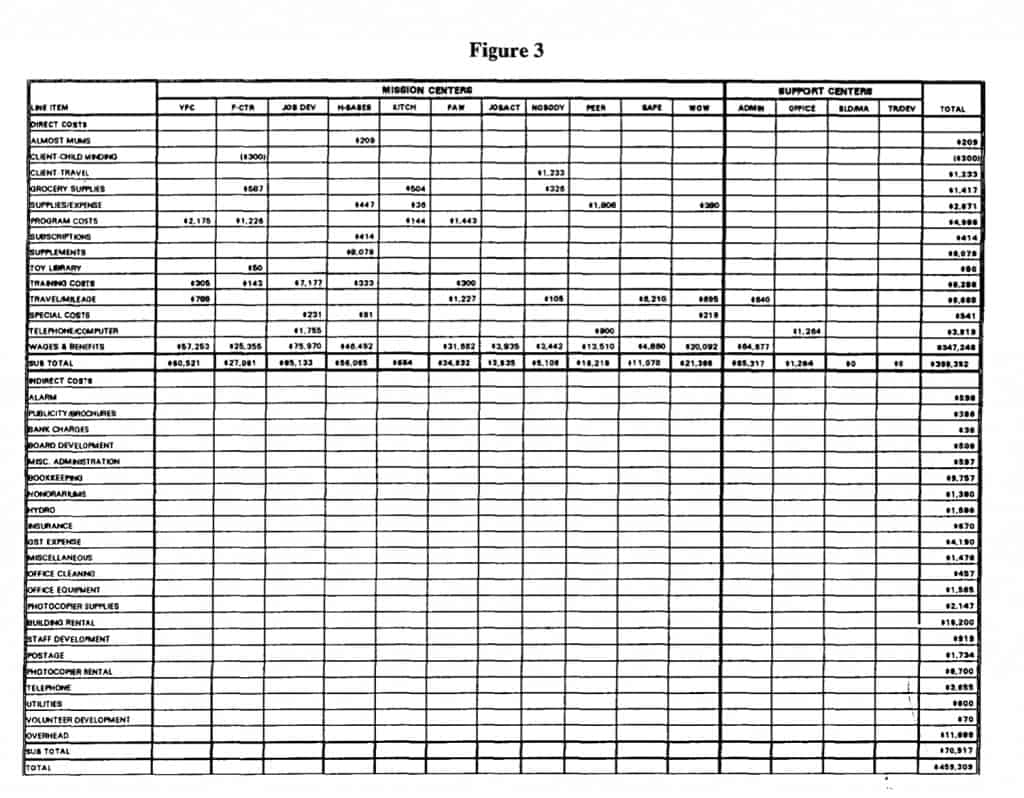

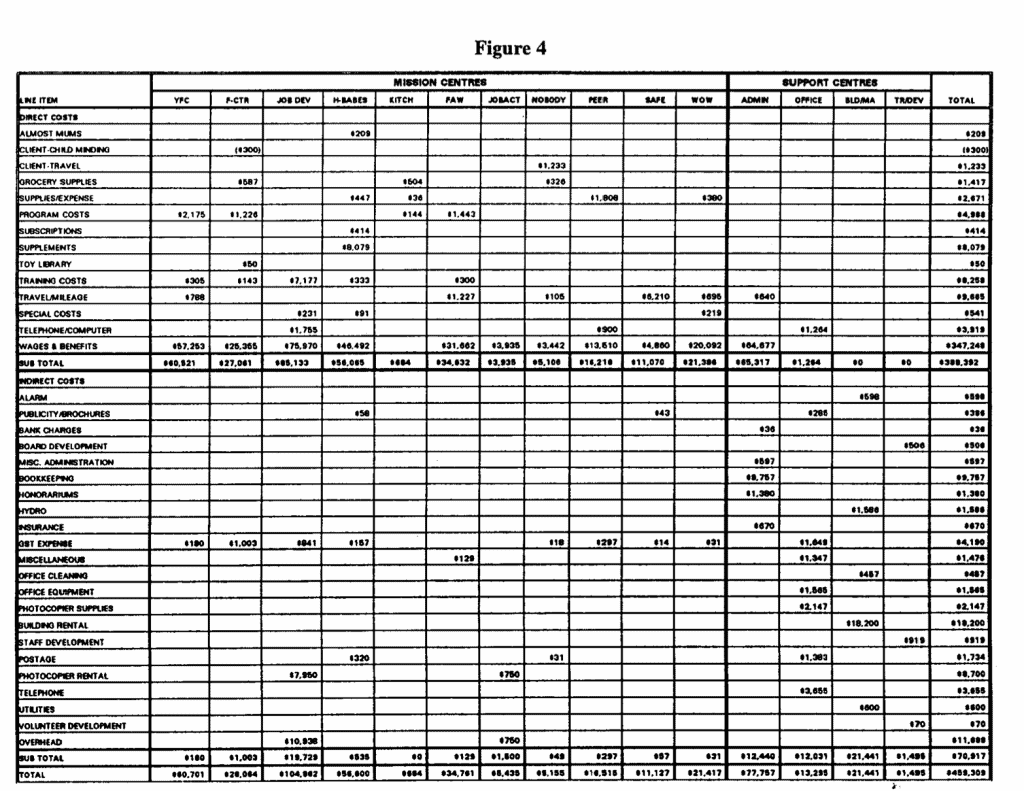

Classifying Direct and Allocating Indirect Costs to Cost Centres

The distinction between direct and indirect costs relates to whether or not costs can be attributed or traced to the cost centre in question. Direct costs are those costs that can be clearly associated with, or physically traced to, particular cost centres; indirect costs apply to more than one centre. Both mission and support centres can therefore have direct as well as indirect costs and, whereas direct costs can be assigned directly, indirect costs must be assigned indirectly, that is, using a formula (a “first-stage” allocation base, as distinct from a “second stage” allocation base which is used to allocate overhead cost centres to mission centres) to divide them as fairly as possible among the centres to which they relate. This is shown in Figure 3. (Appendix p. 23.)

The allocation of indirect costs to their appropriate centres was an interesting exercise. Alarm, Hydro, Office Cleaning and Utilities, were allocated in total to BLD/MA. Bank charges, Miscellaneous Administration, Bookkeeping, Honorariums, and Insurance were all allocated to ADMIN. Board Development, Staff Development and Volunteer Development were allocated fully to TR/DEV. Office Equipment, Telephone, and Photocopier Supplies were allocated fully to OFFICE. Publicity/Brochures was allocated among H-BABES, SAFE and OFFICE on the basis of an estimate of their shares of specific and general promotion. GST Expense was allocated on the basis of an estimate of purchasing activity in the various centres. Miscellaneous was allocated on the basis of relative usage between FAW and OFFICE. Building Rental presented an interesting allocation problem since VCC’s programs operate out of a central facility where floor space is not specifically divided among most of these programs. Considering this, Building Rental was allocated in total to the BLD/MA support centre. Postage, Photocopier Rental, and Overhead were allocated among centres on the basis of an estimate of usage. The allocation of indirect costs is detailed in Figure 4. (Appendix p. 24.)

The administrator is now in a position to address the first part of the first cost objective. Adding up the totals in the support centre columns, almost 25 per cent of the total expenditures in the vee are accounted for by overhead costs.

This information could sustain, for instance, an application for funding which included a justified general overhead percentage.

But there is still much to be done. If the administrator is to address the Board’s interest in the full cost of Administration (now defined as a support centre) and of front-line programs (now classified as mission centres) and in the unit cost of dealing with clients, the support centre costs, or organizational overheads, must be allocated to the mission centres.

The Allocation of Support Centre Costs (the Stepdown Process)

The second stage of cost allocation is the process of distributing support centre costs among mission centres in order to determine the full cost of each mission centre. Before overhead costs can actually be allocated, however, the administrator must first determine the allocation model and second, the set of allocation bases.

The Allocation Model

The allocation model requires the conceptualization of how overhead costs actually work in the organization.

The most basic, and least accurate, allocates the total costs of each support centre directly to the various mission centres. This approach is simple but least accurate because it ignores the services that support centres render to each other.

The most accurate, but most complex, recognizes the complete set of reciprocal relationships among interdependent support centres and solves a set of simultaneous equations to determine the reciprocal allocation of support centre costs before allocating support centre costs to the mission centres. For two support centres, this involves two equations in two unknowns and is relatively simple, but the process becomes more complex as the number of support centres increases. The increased computational complexity can be easily addressed by using a computer, but we found that the it_J.creased conceptual complexity also makes this approach much more difficult to explain to users.

The compromise model, which is always much more accurate than simple direct allocation and is usually acceptably close in accuracy to the reciprocal model, is the stepdown model. This approach recognizes that support centres serve other support centres as well as mission centres, but recognizes that service in a linear, approximate way rather than a fully reciprocal way. Essentially, the set of support centres is arranged in order from that which serves most other support centres to that serving least. Beginning with the support centre that serves most other support centres, the costs of that centre are “stepped down”, i.e., allocated in a cascading way, onto all the other support centres and the mission centres. That completely allocated support centre plays no further part in the allocation process. The procedure is then repeated for each support centre in turn until the costs of all support centres are fully allocated to the set of mission centres. This method ignores reciprocity, but allows managers to reflect on the set of support centres in a functional way, as a working model of organizational activity. It emerged really as a model for the expression of management’s assumptions about how the organization worked.

Allocation Bases

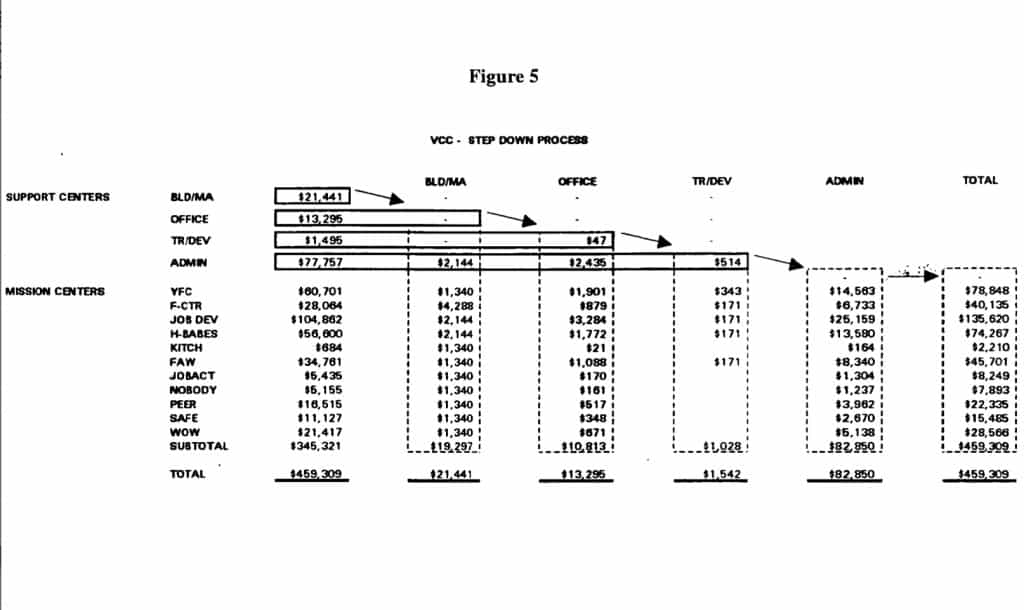

The selection of allocation bases parallels the use of formulae to allocate indirect costs among mission and support centres; the most appropriate base is obviously that which most accurately reflects the use of support centres by mission centres. The allocation formulae have to recognize that support centres may serve other support centres as well as mission centres; the procedure for stepping down support centres into mission centres is detailed in Figure 5. (Appendix p. 25.)

First, Building and Maintenance (BLD/MA) was charged across the remaining mission and support centres. Where possible, this was accomplished through an estimate of floor space usage. Family Centre (F-CTR) was allocated 20 per cent of BLD/MA, Healthy Babies (H-BABES) 10 per cent, Job Development (JOB DEV) 10 per cent and Administration (ADMIN) 10 per cent. The remaining 50 per cent of costs was allocated evenly among the rest of the mission centres. No BLD/MA costs were allocated to the OFFICE and TR/DEV support centres.

Second, the OFFICE support centre was stepped-down across all of the remaining mission and support centres as a percentage of total expenditure.

Third, Training and Development (TR/DEV) was allocated on the basis of the number of Full Time Equivalent (FTE) staff in each mission and support centre.

Finally, in the absence of data regarding how the administrator, the bookkeeper and other managers spent their time on the mission centres, Administration (ADMIN) was allocated as a percentage of the total expenditure of each of the mission centres.

The administrator is now in a position to address the second part of the first cost objective and the second cost objective. Figure 5 shows that the full cost of the ADMIN support centre, including an allocated share of the other support centre costs, is $82,850, and also shows in the final column the full cost of each of the 11 mission centres. This information could be used for comparison with like organizations and in dealing with unsubstantiated assertions about how much of the organization’s resources is consumed by Administration.

How interesting the data in Figure 5 are, depends, of course, on comparable figures in similar organizations and on figures for previous years (if available) for VCC. Since interest in some unit cost figures has been expressed, the Administrator has to turn to a final step to provide this information.

Determining the Unit Costs of Client Services

The calculation of unit costs obviously requires a definition of “unit”. The administrator has two major choices in calculating cost per client: the process method and the job order method. The process method is used when all units of output are homogeneous, e.g., in many manufacturing processes. The job order method is used when units of output are different, e.g., in enterprises such as an automobile repair shop. Using the process method, full mission centre costs for the accounting period are calculated using the steps described above and are then divided by the number of units of output to give unit cost. Using the job order method, all direct costs associated with a particular job are collected separately on a job order record and indirect costs are assigned to each job using an overhead rate. Many cost accounting systems have features of both process and job-order costing.

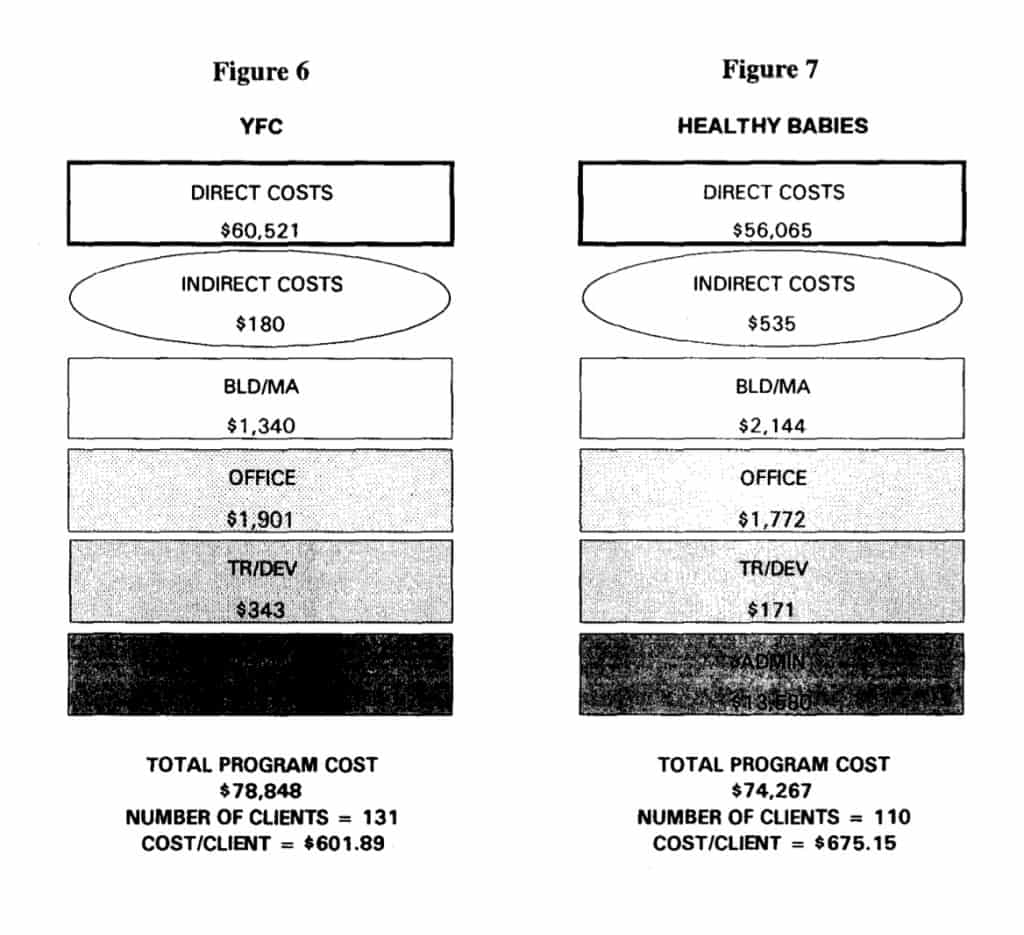

In VCC, the full mission centre costs can be used to calculate the unit cost of client services (Figure 6 and Figure 7). (Appendix p. 26.) For instance, to determine the cost of providing service for a client in Youth and Family Counselling (YFC), the total program cost is divided, using the process costing model, by the total number of clients using this service. Since the program cost was $78,848 and 131 clients used the program, the cost per client was $601.89. Similarly, the cost of serving a client in the Healthy Babies program averages $675.15 ($74,267 program cost for 110 clients).

A much simplified job order costing system for clients can be illustrated by postulating circumstances in which the funding agency for vee proposes that additional counselling services be given to designated clients, and that the reimbursement price for each such client be determined by adding to the YFC process-based unit cost of $601.89/client, an amount to cover the additional hours of counselling at some negotiated rate per hour. If designated clients require 10 additional hours of counselling at a negotiated rate of $40/hour, the additional “job order” charge would be $400, giving a cost/client for designated clients of $601.89 + $400 = $1,001.89.

The Achievement of Cost Objectives

Using the relatively simple cost accounting model illustrated in Figures 6 and 7, the Administrator is now in a position to provide the Board with information on the specified cost objectives. Four broad areas of overhead or support activities have been classified-Administration, Office Expenses, Building and Maintenance, and Training and Development-and these overhead areas account for almost 25 per cent of total expenditures in VCC. Using one set of explicit allocation rules to allocate indirect costs to the various mission centres and support centres and another explicit set to step down the total costs of the support centres in a defined order to the remaining support centres and the mission centres, the administrator can demonstrate the full costs, including an appropriate share of organizational overhead, of each mission centre. Further, using a simple process model, the Administrator can divide the full cost of each mission centre by the number of clients served to arrive at the unit cost of a client and can supplement that unit cost information, if required for reimbursement purposes, by specific job-order information for particular clients.

V. Conclusion

The concept of cost in human service NPOs in British Columbia is well understood neither by internal decision-makers nor by external funders. Lineitem financial information, either in the form of budgets or financial statements, is frequently and erroneously believed to convey useful information on program costs. This paper is specifically concerned with the importance of understanding and including in cost calculations the cost of the support or overhead activities that are necessary to sustain direct client service activities. It has attempted to demonstrate that information on the nature and role of overhead costs, and the derivative information on the full and unit costs of client service programs can be generated using a relatively simple model. Essentially, the model invites managers to start with simple line-item budget information, then to formalize the assumptions with which they are working intuitively, and finally to explore the implications of these assumptions. Further, we have argued that cost information is necessary for internal and external accountability in human service NPOs. Information on the relative costs of direct client service programs, fund-raising programs, and internal support programs contributes to informed resource allocation by managers and boards internally and funders and evaluators/auditors externally, and is essential where funding is geared to formal reimbursement. Full cost information contributes to improved strategic planning, programming, and performance budgeting and to associated performance monitoring and evaluation. The controllable costs component of cost centres also serves as the basis for responsibility-centre budgeting and monitoring. Human service NPOs are rightly concerned about effectiveness-about doing the right thing. This paper has argued that they should also be concerned about efficiency-about doing the thing right-and that such information is within the reach of all managers and boards using their line-item budgets and a willingness to articulate and test their assumption about how the organization functions.

REFERENCES

Anthony, R.N. and D.W. Young. Management Control in Non-Profit Organizations, 5th ed.

Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin, 1994.

Cutt, James et al. From Financial Statements To Cost Information: Efficient Resource

Utilization In Non-Profit Organizations. Victoria: Centre for Public Sector Studies, 1994. Young, D.W. Financial Control In Health Care. Homewood, IL: Dow-Jones-Irwin, 1984.