We often frame international aid as charity, a nice-to-have when the books balance, Plan Canada’s Lindsay Glassco writes. But in a deeply connected world, shaped by conflict, climate, and contagion, investing in resilience elsewhere is a strategic way to reinforce it here.

The doctor treating your child’s fever. The jeans piling up in your closet. The family down the street sending money back home. These aren’t separate stories; they are threads in a global system that Canada relies on – and they are quietly unravelling.

In 1991, I witnessed firsthand how these threads connect us. Through the World University Service of Canada, I had moved to Lesotho in Southern Africa to teach for two years during what became one of the worst droughts in the country’s history. In this tiny mountain kingdom, children typically went to school. But during the drought, many stopped coming, too hungry to focus. A modest school meal program, funded by Canadian aid, brought them back. A plate of food was all it took to reopen the door to education – and to the possibility of a different future.

In the years since, Lesotho has become a denim manufacturing hub, producing more than 25 million pairs of jeans annually for global brands like Levi’s and Calvin Klein. These jobs put food on tables, pay school fees, and move families forward.

Today, hard-won economic progress is under threat. In March, President Donald Trump proposed a 50% tariff on Lesotho – a country, he claimed, “no one’s ever heard of.” If implemented, the Lesotho Textile Exporters Association estimates that 15,000 jobs would be lost within a year – nearly 4% of the country’s formal employment in this one sector alone.

It’s tempting to file this as an “over there” problem: distressing but distant. But policies like this set off a chain reaction that doesn’t stop at any one border. When jobs disappear, families lose income. When economies collapse, desperation grows. When local systems break down, people become vulnerable to exploitation and migrate in search of safety.

We rarely connect the cracks we see at home to the support systems we’re pulling away from abroad.

Here in Canada, we talk about overwhelmed hospitals, labour shortages, and growing polarization. But we rarely connect the cracks we see at home to the support systems we’re pulling away from abroad.

Look no further than your family doctor or the nearest emergency room: nearly one in three physicians in Canada was trained internationally – many from countries like Nigeria, South Africa, and India, where we’ve scaled back development investments. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization warns of a global shortfall of 10 million health workers by 2030. Hardest hit will be the low- and middle-income countries we increasingly depend on to staff our hospitals and long-term care homes.

Beyond the short-sightedness of draining the very systems we’re relying on, wealthier countries like Canada must grapple with the ethics of recruiting health professionals from countries with urgent needs of their own. But pulling back isn’t the answer. Investing in global health systems – through a coordinated national aid strategy that expands training capacity, supports return-home incentives, or compensates source countries – is a more ethical, sustainable approach. It’s how we build global health equity, not erode it.

A similar blind spot exists in our immigration debates. Every year, people in Canada send more than $8 billion in remittances to support loved ones back home – more than our entire foreign aid budget. These funds help reduce poverty, stabilize fragile economies, and cover essentials like food, education, and medicine. They are, in effect, a quiet, citizen-led form of foreign aid – personal, direct, and deeply effective.

We could amplify their impact with better coordination; for example, reducing transfer fees, offering matching funds during crises, or integrating remittances more intentionally into broader development strategies. These dollars may be private, but their public impact is undeniable.

We’re similarly connected through climate change. According to the United Nations, climate-related disasters have increased fivefold in the past 50 years. Crops fail. Families are displaced. Children – especially girls, who must fetch water from increasingly long distances – stop going to school. These are not isolated disruptions; they compound existing vulnerabilities like doctor shortages, factory closures, or levels of inequality, in places already on the economic edge.

In Canada, climate-linked asylum claims have risen more than 60% in the past five years. In 2018, there were roughly 55,000 total asylum claims – a number that’s steadily rising as environmental instability pushes more families to seek safety across borders.

This is resilience infrastructure: quiet, load-bearing, and invisible until it fails.

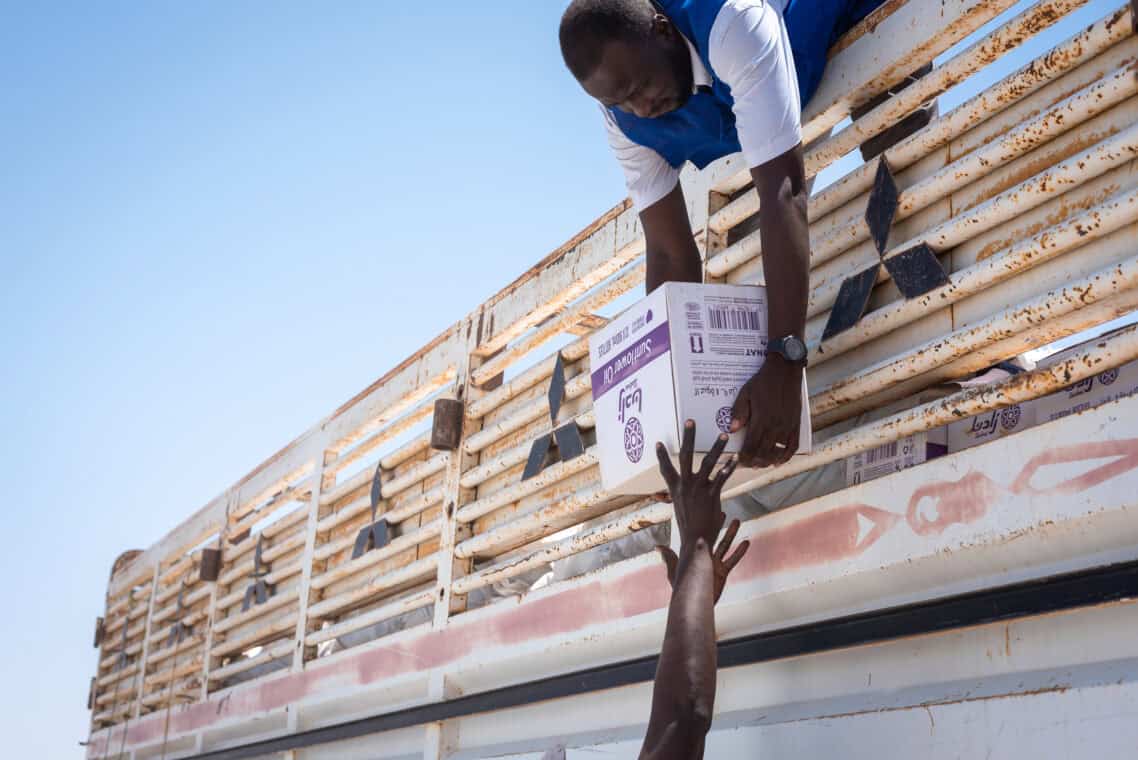

We often frame foreign aid as charity, a nice-to-have when the books balance. But aid is infrastructure. It’s how we invest in the systems that protect people abroad and reinforce the systems Canadians depend on here at home. Some argue these are dependencies, but I would argue that’s the wrong lens. These aren’t relationships to sever, but systems to strengthen. In a deeply connected world, investing in resilience elsewhere is a strategic way to reinforce it here.

Canada’s own data makes the case. According to the Canadian International Development Platform, every dollar invested in foreign aid generates $1.80 in Canadian exports. At Plan International Canada, we see this return on investment through projects that connect Canadian expertise with regions working to increase opportunity and long-term stability. In Kenya, for example, Plan, the Government of Canada, and the Jane Goodall Institute are partnering to bring BC-based Cascadia Seaweed’s expertise in sustainable seaweed farming to local producers. The program’s goal is to improve yields, develop new products, and access new markets. That’s Canadian innovation, creating Canadian jobs and building resilience abroad.

In a world shaped by conflict, climate, and contagion, this is resilience infrastructure: quiet, load-bearing, and invisible until it fails. So, the next time you visit your doctor, pull on your jeans, or encounter a climate refugee, remember the invisible threads connecting these stories and holding our society together.