For each of these organizations, creating a “successful” visual campaign was about authenticity, bold storytelling, and navigating ethical complexities.

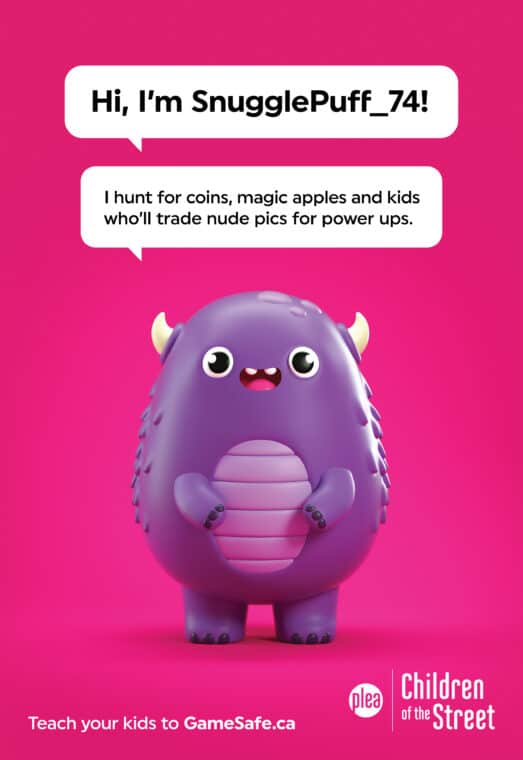

When Children of the Street created a social media video series of animated gaming avatars warning parents about the growing danger of online predators attempting to exploit children through video games, the Vancouver-based program, which is dedicated to preventing child sexual exploitation and human trafficking, wasn’t expecting to become the victim of their own success.

The program, which currently sits within PLEA Community Services Society of BC, is known for creating bold campaigns, but “Dangerously Cute” was the first to go viral. It’s the kind of organic marketing most charities dream of, and for Children of the Street, it only proved the very point they were trying to make: that the internet isn’t a safe place for kids to be sharing images.

Snugglepuff_74, one of the campaign’s animated avatars, is a cutesy smiling purple monster you want to scoop up and squeeze. Snugglepuff tells you in a child-friendly voice that his three special powers are “thunder stomps” (he cracks the ground open with his stubby foot), “horn beams” (he shoots out rainbows from his tiny horns), and then, as his eyes narrow, his voice deepens, and the music darkens, Snugglepuff tells you his third superpower: “tricking your kids into sending me nude photos.”

With more than 66 million impressions, the campaign was deemed a roaring success. But “success” is a loaded word and should be met with curiosity and caution. While numbers paint a less nuanced picture of widespread impact, they don’t always reflect the ethical challenges or the potential unintended consequences that come with such digital visibility. At the same time, success can mean something less quantitative – improving someone’s outlook, changing someone’s mind, challenging the status quo of an entire industry. Here’s how three Canadian charities overcame ethical dilemmas through visual campaigns, and why success often requires a deeper look.

It was 2021, the height of the pandemic, and kids were spending more time than ever gaming from their bedrooms. When Dangerously Cute went live, creators on TikTok embraced it, making fan art, stitches, and their own accounts featuring Snugglepuff.

In one stitch, a TikToker records his reaction as he watches the three avatar videos. You see his face change from happy to frightened for each avatar. At the end, the camera zooms in, showing a single tear running down his face. The video got more than one million likes. But in other appropriations, TikTokers exploited the darker side of the campaign. “What happened with our video with that campaign is exactly what can happen with anyone’s photograph,” says Jen Graham, director of Children of the Street. “We completely lost control, and there’s nothing we could do to get that back.”

It’s been proven time and time again that when you can create a real standout that attracts eyeballs and attention, it sticks with people.

Lisa Lebedovich, Will Creative

Lisa Lebedovich, the creative director behind Dangerously Cute, sees the campaign going viral as a success. “It’s been proven time and time again that when you can create a real standout that attracts eyeballs and attention, it sticks with people,” she says. Lebedovich works for marketing agency Will Creative and has worked with Children of the Street for nearly 20 years. For the past several years, Will Creative has produced its campaigns pro bono.

Lebedovich explains that she’s looking for what’s “water-cooler worthy,” something that, when you walk into an office, everyone’s talking about. “It’s not going to be something that’s super mainstream,” she says. “The [mainstream] message is diluted to be safe. It’s the things that stand out that stay in our memories.”

It can be really difficult for some charities to really step out on that ledge. You’ve got to be prepared to be bold.

Jen Graham, Children of the Street

Graham agrees. She believes that the bolder you are, the more eyes you’ll get on a campaign. “It can be really difficult for some charities to really step out on that ledge,” she says. With funding partners to consider, it’s easy for charities to dilute campaigns to the point where they won’t work anymore, she adds. “You’ve got to be prepared to be bold.”

This year, Children of the Street released its boldest yet. “Don’t put your d*ck here” is a campaign aimed at curbing the rise of sextortion among teen boys by demonstrating the hazards of sharing nudes. Graham wanted the campaign to be funny – humour being a good entry point for talking about difficult issues, particularly among teen boys. It wasn’t an easy green light to give, though. Graham was nervous the schools would reject the posters the charity usually distributes, based on the language. So rather than delivering posters as usual, they emailed schools to let them know about the campaign and asked schools to opt in to receiving the posters. “I knew not all schools would want that language up on their wall for whatever reason, and that’s fine,” she says. “You just have to be okay with that trade-off . . . because if we’re going to talk to kids about what’s going on with them, then we need to use language that they relate to.”

When CBC ran a feature highlighting the campaign, becoming the second-most-read article the week it ran, Graham knew the trade had paid off.

Graham doesn’t believe such impact would be possible without a creative partner. “You’re so in the weeds of the issue, working on it every day, that you need somebody to filter out the stuff that’s going to play to a broader audience,” she says. “They also do things that we just wouldn’t have time for.” For Dangerously Cute, Will Creative designers spent several hours playing video games to get into the minds of the kids being targeted by online predators while playing. “Everyone that was working on the project played those games to see how easy it was to start chatting with children,” Lebedovich says. “That kind of hands-on learning is invaluable.”

Research is one thing, but Lebedovich emphasizes the importance of trust. “They educate us on everything that’s happening in their world, the issues with statistics, what’s being done, what’s not being done. And so we trust them as the experts, and they also really trust us being the experts on the creative end of things.”

A shift toward local perspectives

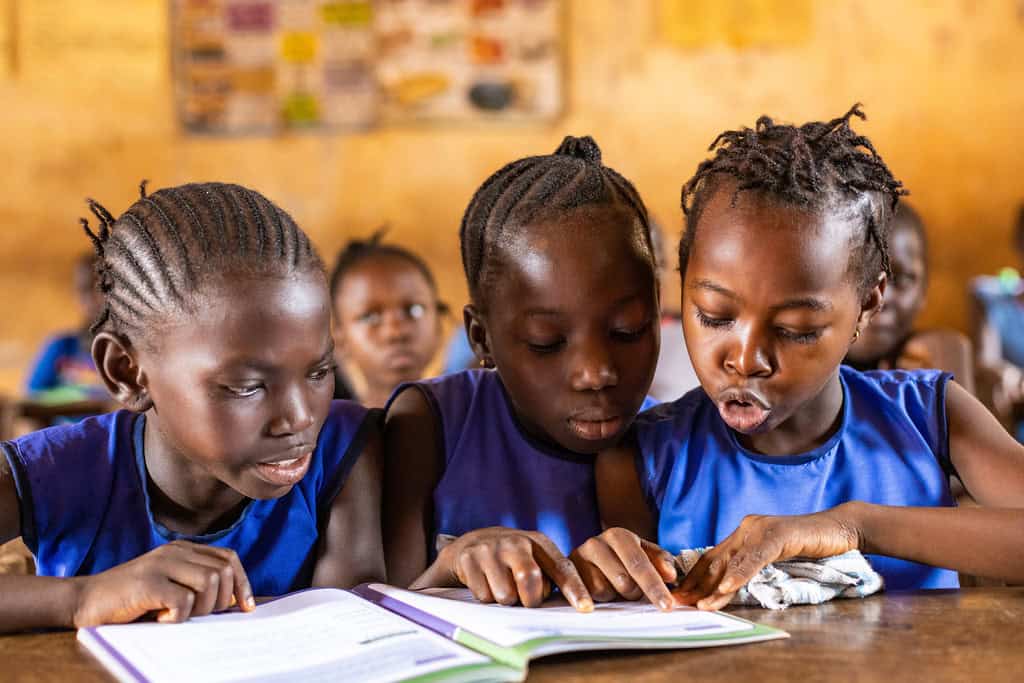

For international non-governmental organization Code, trusting the experts looks a little different.

Andrea Helfer has worked with photographer and photojournalist Peter Bragg for 15 years, first at WaterAid, then with Code, where she is now director of fund development and marketing for the non-profit. With a mission of advancing literacy globally, Helfer wanted to shift away from the NGO working with parachute photographers like Bragg to align with Code’s community-based values. “It only makes sense that we are engaging with storytellers locally, who are really better positioned than anyone to capture photos in a way that is compelling, sensitive, and authentically their story,” she says.

Bragg “is so charming, so disarming, and he’s got a great sense of humour. He’s a consummate professional,” Helfer says. “But the fact of the matter is that he’s a white, North American male, and that carries with it a certain amount of baggage into a community.” She’s been working with a local Sierra Leone photographer, Hickmatu Leigh; there’s a different kind of interaction that occurs, Helfer says, when working with someone who speaks the language and understands the culture.

It only makes sense that we are engaging with storytellers locally, who are better positioned than anyone to capture photos in a way that is compelling, sensitive, and authentically their story.

Andrea Helfer, Code

The shift toward working with local photographers, Helfer says, aligns with Code’s vision and values “of amplifying local voice, local self-storytelling, local perspectives.” It also makes sense economically. The footprint of sending a Canadian photographer overseas is significant compared to the cost effectiveness of working with a locally engaged photographer. Code is able to gather much more footage for the same level of investment. That doesn’t mean she won’t work with a North American or European photographer like Bragg again, though: “I think it’s really helpful and powerful to have a roster of photographers you’re able to select from based on whatever assignment you have in mind.”

Helfer says that Code takes a photo-first approach to communication. “Photography is always front and centre,” she says. With a donor base that is largely Canadian, Helfer says that the onus is on Code to help the Canadian public feel inspired to understand the need and complexity of Code’s work. “And that is most effectively done through an image. And when that image can be complemented by a compelling narrative as well, I mean, that’s golden, isn’t it?”

Breaking barriers through photography

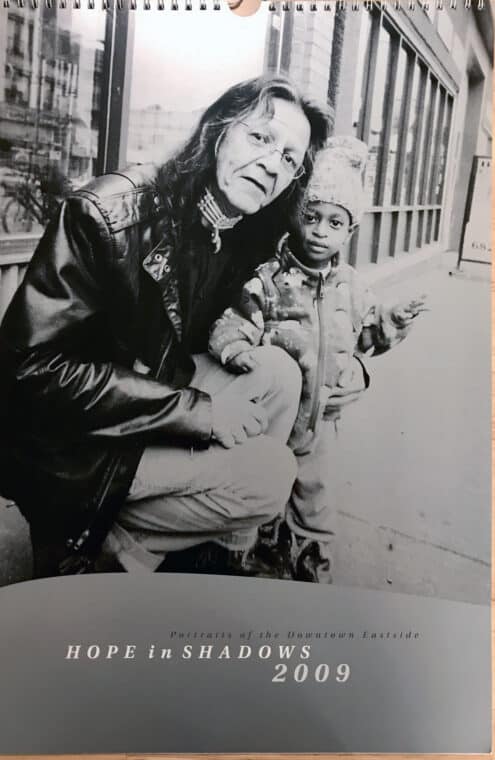

Photography is also at the core of the work of Megaphone, a Vancouver-based charity that seeks to reshape societal perceptions of poverty through literary and journalistic publications created and sold by the very people experiencing poverty. Through Megaphone’s three pillar publications – the monthly street paper Megaphone Magazine, the annual literary anthology Voices of the Street, and the Hope in Shadows calendar – readers are able to understand Vancouver’s poorest neighbourhood, the Downtown Eastside, through the lens of lived experience.

The neighbourhood often appears on the international stage in global media discussions about homelessness and drug policy, often draped with misinformation, only reinforcing harmful stereotypes. Megaphone aims to undo at least some of that damage – empowering the community to tell its own story. Editorial and program director Paula Carlson says the Hope in Shadows calendar photo contest is the most popular publication. “A lot of people know Hope in Shadows before they realize it’s Megaphone,” she says. “They’re like, ‘Oh yeah, that thing with all the neat photos in it.’”

A lot of people know Hope in Shadows before they realize it’s Megaphone. They’re like, ‘Oh yeah, that thing with all the neat photos in it.’

Paula Carlson, Megaphone

In its 21st year, Hope in Shadows gives visual storytellers from the Downtown Eastside a platform to break stereotypes and share the vision of themselves and their neighbourhood authentically. “I think why it’s impactful is [that readers] get to see themselves in it – it creates common ground,” Carlson explains. “They’ll see someone with a cart full of plants, or playing ball with their kids, or in a community garden, or walking their dog, and they don’t just see other people when they see that, they see themselves. And I think that’s done so easily through photographs, right?”

Each year, Megaphone, situated in the heart of the Downtown Eastside, organizes a Hope in Shadows “camera hand-out day,” whereby any resident who wants to participate in the calendar photo contest can take part in a photography workshop and walk away with a disposable camera and a photography brief. During the workshop, participants learn about the basics of photography – light, shadow, composition – and some creative techniques to play with. They’re also taught about consent (without which photos can’t be considered for the calendar) and are given a broad theme to work with.

Participants have one week to fill their 36 frames (old-school film cameras all the way) before a team of community judges followed by a public voting process whittles down submissions from 2,500 images to the top 13 winners. All winners and 12 runners-up receive prize money, and Megaphone vendors are able to buy the calendar for half of its $20 market value, keeping the profits for themselves.

Since its inception, the charity has distributed $1.3 million to its vendors through the sale of the Hope in Shadows calendar. But what’s really rewarding, Carlson says, is seeing how people respond to having their photo chosen and being a part of the contest. It all starts with the camera workshop: “It’s the first time maybe someone’s taking the time to explain these things, and they just really enjoy the learning experience.”

Carlson says the competition has even reunited estranged family members because of its positive impact on winners, who can proudly share the calendar they’re featured in.

***

In the non-profit world, success isn’t always measurable through numbers. It’s often found in less tangible outcomes: through losing control of the message and being okay with it, through shutting one door to open another, through taking risks. In all cases, though, success was about authenticity, bold storytelling, and navigating the ethical complexities that come with the responsibility of influence.