What happens when we neglect to disseminate timely, factual information in the languages newcomers speak and in the digital spaces they use?

I imagine recounting the COVID-19 pandemic to my children in 20 years’ time: a pause for effect while their school-aged faces gawk incredulously as I describe the absurdist chaos that characterized our clumsy response to the defining public health emergency of the 2020s. Hospital nurses resigning from work to avoid mandatory vaccination requirements, the rows upon rows of empty toilet-paper aisles at the grocery store, and a curious societal predilection for hand sanitizer. On my phone (or whatever device we’ll be using by then), I produce a screenshot of a WhatsApp message dated January 2021, forwarded to me by their great-grandmother. “Stay away from Coca-Cola,” she warned. “It contains the COVID-19 virus. Here’s the proof.” They struggle to understand how someone like Rose could be so naive. Superstitious as she is, the woman is steadfast in her empiricism, wary of what she’s learned through a staticky game of telephone. The older one giggles; her brother joins after a moment – skeptical. On the surface he trusts his sister’s judgment; I find it amusing how he glances uncertainly at the brown drink in his cup, gone flat.

I tell them about how the spread of COVID-19 exploded within newcomer communities. Data released by Ottawa Public Health in late 2020 indicated that African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) people made up 37% of recorded cases, yet these groups represented only 7% of Ottawa’s population. A study later found that “the spread of disinformation, a lack of timely and consistent information, language barriers, and structural racism left Black people uniquely and disproportionately vulnerable to the COVID-19 virus and the wider impacts of the pandemic.”

I anticipate the disbelief of my unborn kin. Why wasn’t the government making sure information was easy for people to understand in the languages they speak? A year into the pandemic, CBC’s annual survey on media and technology found that newcomers were more likely to use digital messaging apps like WhatsApp to communicate, a valuable conclusion that newcomer community leaders and the organizations supporting them had come to anecdotally and incorporated into their info-sharing tactics long before the pandemic. Why didn’t public health officials leverage this insight to communicate with newcomers about COVID-19 through the channels they already use, and in turn, counter the spread of disinformation?

Future generations will criticize our cohort’s belated response to the global pandemic – our disregard for the particular needs of newcomer audiences, our overreliance on non-profit organizations to fill the gap (on tighter budgets and with fewer staff). Hopefully by the time they’re in charge, we’ll have learned to prioritize information delivery as an essential service, particularly toward newcomer audiences, that when the lesser among us have access to information on a timely basis, the whole of society benefits. This is the ambition of organizations like Refugee 613 – an Ottawa non-profit that helps newcomers by creating plain-language, fact-checked information on diverse topics related to starting a life in Canada. When the pandemic hit, Refugee 613 partnered with community leaders and service providers to disseminate fact sheets, videos, and infographics about COVID-19 and the vaccine within digital spaces newcomers use. It was easy to share the multilingual resources through platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram, and Refugee 613 distributed content only after it had been reviewed for cultural accuracy by members of each language community.

Reuben Nashali first encountered Refugee 613 in the summer of 2020. He connected with Louisa Taylor, the director, when the organization recruited Nashali to translate COVID-19 videos into Swahili. A few months later, he landed an eight-week internship with Refugee 613 through the Canada Summer Jobs program. Nashali credits his time at the organization with opening his eyes to the disparities in the way information about COVID-19 was being created and disseminated. Like everyone else, he assumed that news about the pandemic was reaching newcomers at the same rate as their Canadian-born or longer-established counterparts, and those with a solid grasp of English and French. Nashali realized just how seriously his own community had been left out of the loop after directing the members of his church toward the videos he helped produce.

The language people use to communicate the news . . . really matters. It can make people consume the news or completely ignore the news.

Reuben Nashali, former Refugee 613 intern

“That experience taught me something that I had always taken for granted. The language people use to communicate the news varies from community to community; [language] really matters. It can make people consume the news or completely ignore the news,” he says.

Nashali recalls seeing a significant change in the attitudes and behaviour of his community after the Swahili videos began circulating. Previously, he had heard erroneous comments about ACB people being immune to COVID-19. Later, he observed more of his fellow congregants wearing masks to mitigate the spread of the virus. The most significant change, he says, was in people’s acceptance of the vaccine. “I came to realize newcomer populations consume information differently. Particularly Swahili speakers, they relied on WhatsApp video-sharing. Those videos were misleading,” he adds.

In July 2021, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) announced it was funding several community-based organizations to “support populations disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 make informed vaccination choices by crowding out misinformation and providing culturally relevant and science-based information.” Together with the University of Toronto, Refugee 613 researched how vaccine information and misinformation circulated in newcomer digital spaces. Then, they created lists of websites and social media accounts to help members of nine language communities access trusted sources of information, and even put together a tip sheet for newcomers navigating strained relationships with friends and family who share misinformation online. An interactive workshop led by Anthony Morgan, host of The Nature of Things on CBC, helped members of racialized and diaspora communities sharpen their ability to find and share factual information with online audiences. The project showed the value of communicating consistently with newcomer communities, developing digital content to maximize the spread of factual information, and providing resources in the languages newcomers speak. When PHAC disseminated videos and images from their Vaccines & You campaign through a Telegram group for Arabic speakers moderated by Refugee 613, group members said they appreciated having access to information they knew they could trust, and they were more likely to share it with family members or friends in their countries of origin or people who otherwise did not have access to the right information.

Refugee 613’s initiative to combat the spread of mis- and disinformation about vaccines in newcomer digital spaces ended in spring of 2023. Like many Canadian non-profits, Refugee 613 relies heavily on short-term, project-based funding agreements with the federal government. Although it continues to produce health and settlement content in multiple languages through a project funded by Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), that funding too is short-term. Near the end of every funding period, non-profits must submit a new project proposal if they wish for their work to continue. And if IRCC agrees to continue funding the work past its current end date of March 2024, there is no guarantee there will be no break in service, or that it will be in the same capacity as the year prior.

Canada is . . . aiming for 500,000 arrivals in 2025, but it lacks a plan for ensuring that newcomers with language barriers can get the information they need.

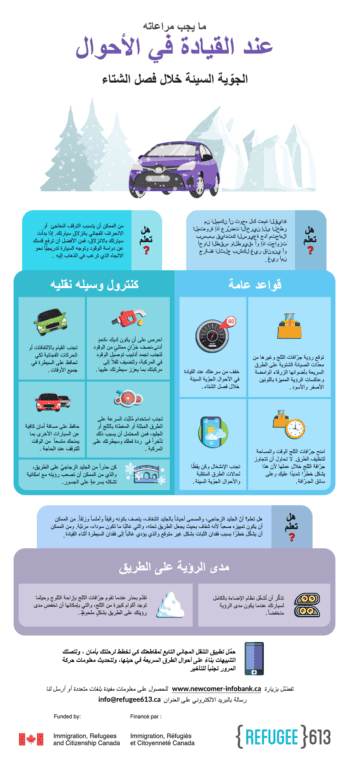

The same year Refugee 613 sunsetted the Vaccine Misinformation project, two others – one that allowed for the creation of multilingual resources for newcomers and a Telegram group that provides settlement information in Dari and Pashto to more than 750 Afghans – were combined into one funding agreement. Staff from both projects had to be let go, and the organization pivoted by homing in on the questions from their Afghan clients about starting a life in Canada, then adapting each answer into infographics and fact sheets for additional language communities. This means newcomers can now count on Refugee 613 for help in assessing their eligibility for the Canada Dental Benefit, or to determine if they’re being taken advantage of by a landlord. But the question is for how much longer? Canada is currently operating on its most ambitious immigration targets ever, aiming for 500,000 arrivals in 2025, but it lacks a plan for ensuring that newcomers with language barriers can get the information they need. The language challenge is particularly acute for refugees, and no one is resourced to mass-produce and disseminate multilingual resources about starting a life in Canada for the next influx of arrivals from the 100 million forcibly displaced people around the globe. If we want to create a society with equitable access to information, the way we produce and share information with newcomer communities should reflect their media consumption habits, and organizations like Refugee 613 need long-term sustainable funding.

***

Since its inception in October 2015, Refugee 613 has played a pivotal role in facilitating communication on refugee issues between civil-society and grassroots organizations in Ottawa. During the Syrian refugee crisis, Refugee 613 convened newcomer-serving organizations to foster collaboration and helped to orient citizens and faith groups wanting to sponsor Syrian refugees. Ottawa, where Refugee 613 is based, became the top city for welcoming refugees in 2018 through the Blended Visa Office-Referred Program – a refugee resettlement pathway that matches refugees abroad with Canadians to whom they have no family or personal ties. Building on this grassroots engagement, Refugee 613 has become a trusted source of multilingual information across Canada for newcomers and the communities that support them.

Fraidoon Latifi, his wife, and three daughters arrived in Ottawa in February 2022, six months after the Taliban seized the capital of Afghanistan and completely upended their lives. Latifi, a licensed psychiatrist, currently works as a client services coordinator for a company offering personal support services. His wife, a gynecologist, chose to go back to school and re-earn her accreditation. It’s a stark difference from the careers they once had, but Latifi is happy his daughters will have a better future than what awaited them in Afghanistan, where the Taliban has gradually rolled back women’s access to education. Latifi joined Refugee 613’s Telegram group for Afghan newcomers shortly after his family arrived, which he says made it much easier for the family to find their footing.

“During our first year [in Canada], the group was really good for us. We received answers in Dari and Pashto. I had a lot of problems at the beginning. For example, registering my daughters at school or the driver’s licence exam. Everything I asked, I received an answer. Every Afghan I know in this group, they’re all satisfied,” he says.

Refugee 613’s future is uncertain – the work of Refugee 613 is fulfilling, if at times undervalued, rewarding even if the gains become grounds to reassert the necessity of our existence, year after year. Given Canada’s ambitious immigration plans, and as the demands of Bill C-18, the Online News Act, result in additional barriers for the 40% of newcomers who rely on social media as their primary news source, it is critical that we continue to fund organizations resourced to close the information gap. This is the kind of society where I hope to raise my children and recount the COVID-19 pandemic, a “back in my day” kind of story where the main character starts out as the underdog but becomes all the wiser for it. Hindsight is 20/20. Let us learn from the disastrous outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic and prioritize timely and factual information delivery to underserved communities.