Introduction

So, is it over? Can we re-boot to “business as usual?” bank profits are up, unemployment down. Was it just another blip in the boom-and-bust cycles of the market or the harbinger of a more significant and permanent change in our economy? If the latter, what does it mean for Canadians’ well-being? What should the community sector—those organizations, associations, and voluntary bodies that contribute so much to the quality of life in our communities—do to prepare itself?

This article2 will argue from the premise that Canadians are living through a transformation that has been accelerated, but not caused, by the economic downturn we are experiencing. More specifically, it will explore some of the implications of this for Canada’s voluntary or community sector (I prefer the term community, as voluntary is often misunderstood to mean volunteer). It will also argue that new models and approaches are urgently required, not just to ensure the health of a sector too long taken for granted in the public realm but to maintain Canadians’ well-being.

New methods and approaches are disruptive. If we believe we face short-term strains, we will respond in traditional ways, tightening belts, and getting on with it; but if we believe we are now in a world of constant, accelerating change, we must become leaders in making Canada and Canadians more resilient, adaptable, and creative in finding sustainable solutions to long-standing social challenges. The argument here is that it is time to re-think our operating models, our function, and our contribution to Canadian society, embracing innovation and re-asserting our role as catalysts, communitybuilders, and creative problem-solvers.

Change : cyclical or structural?

The probabilities are very low that when we get through these times of great economic crisis that we’re going to go back to a period of stability… the good news is that, properly framed, these are wonderful times because it is precisely in times like these when opportunities for massive and lasting contributions go up.

Jim Collins, author of Good to Great and the Social Sectors

Recessions, stock market bubbles, and persistent government deficits are not unusual; growth eventually returns, and the 1990s showed that it is possible for determined government action to eliminate deficits and even run recurrent surpluses. The current recession is already officially over, and we are assured daily that we will shortly be enjoying renewed growth and prosperity (as the federal government’s current advertising campaign asserts: We will come out of this stronger than ever!).

Deeper structural changes, however, affect Canada now: the birth-pangs of the so-called “green” economy, an aging population and the low (or nonexistent) growth of our workforce, and the eastward move of the global economy’s centre of gravity to Asia, The dynamic economies emerging in Asia and Latin America create a competitive environment in which Canada’s lagging productivity (now at only 75% of the U.S. level), deteriorating infrastructure, and often change-resistant institutions put us increasingly at a disadvantage. The present economic shock has accentuated the contrast between the demands of the “old” industrial and natural resource-based economy, exemplified by the automotive and forestry industries, and the need to invest in a new economy based on knowledge, technology, and innovation. In choosing between bailing out General Motors or Nortel, rhetoric about the “knowledge economy” proved no match for the reality of thousands of present-day industrial jobs.

New technologies are profoundly altering mature industrial economies, creating opportunities but also requiring painful adjustments. Workers who have seen their jobs migrate to cheap labour countries are assured that Canadians will move upstream to higher value and better paying occupations in the knowledge economy. Economist Jeff Rubin begs to differ: he argues in his recent book Why Your World is Going to Get a Whole Lot Smaller that the rising cost of oil will overturn the rationale for much off-shored production, even throwing globalization into reverse as countries and communities turn to local sources for food and lower value manufactured goods. Ironically, it may be that new information and communications technologies make it easiest to outsource some services, including the higher value-added items like software design, engineering, and basic research.

Demographic changes are also important: Canada is aging, and its population growth is slowing. The current fertility rate of around 1.6 children per woman means that any growth now is entirely due to immigration. The proportion of people who are no longer in the labour force to those who are is growing 3 so fewer people will be paying the taxes that support government services. Parliamentary Budget Officer Kevin Page estimates that the tax revenue base will be $65 billion smaller in 2013-14, although the finance minister calls this “too pessimistic.”4 Economic growth will slow (because of slow population growth), and the demand for government spending on elderly benefits and health care will increase.

The silver lining to the aging population has been the much anticipated “inter-generational transfer of wealth” (though we have not heard much about this lately). Optimistic estimates of billions of dollars being left by well-off boomers to their heirs have been tempered by a realization of the rising cost of health care, a growing proportion of which will be borne by individuals even under medicare, and by the impact of the market decline on individual and company pension plans. Furthermore, 11 million workers, or 60% of Canada’s workforce, have no pension at all and 45% have neither a pension plan nor an RRSP,5 so some of their accumulated savings will be needed for retirement.

An aging population is not the only demographic change underway. Canada is becoming more urbanized; small towns and rural areas are losing people to the large cities,6 which also has implications for how government services are delivered. Canada is also more diverse, with some cities soon to have a majority of their citizens made up of recent immigrants or Aborginals, groups that often are excluded from full participation in Canadian society.

These changes are already beginning to affect Canada. How ready are we?

Businesses, of course, constantly adapt to changes in the market; successful businesses anticipate those changes, giving them a competitive advantage. In recent years the CEOs of large multinationals have stated that incremental improvement no longer suffices.7

The business environment is undergoing such rapid and far-reaching change that companies are having to re-think their basic business models. This goes beyond the development of new products and processes to re-imagining the nature of their business and/ or their structure and financial models. One CEO referred to living “in a whitewater world.” Examples of disruptive innovations can be seen in the way the pharmaceutical industry has moved from doing in-house research to out-sourcing it. Instead of investing millions of dollars to develop, test, and market new drugs, commercializing the few that showed the greatest potential, the new model outsources much of the cost and risk to smaller, more nimble firms, often start-ups, that focus intensely on one or two products. Once their therapeutic value is proven, the products are licensed or the companies are bought out by “Big Pharma,” which has the financial clout to advertise and sell the new drugs. There are countless other examples, from the music industry to banking and financial services to consumer products (Gillette, for one, has shifted from selling razors to selling blades). What happens when established businesses or even industries do not anticipate change is illustrated by the “Google effect” on newspapers.

Governments have struggled, with less success, to follow suit. Creating profit centres within the public service, establishing public-private partnerships for infrastructure development or service delivery, more transparent budgeting processes, and so on all represent efforts to make government flexible, accountable, and more customer-focused. However, the public sector has significant obstacles and few incentives to spur innovation. Bureaucracies were designed to replace rule by caprice or favoritism with standard practices and uniform treatment. A narrow and rigid focus on financial accountability, with perceived lapses resulting in partisan attacks and media headlines, makes politicians and public servants alike highly risk-averse and unwilling to stray far from conventional thinking even where it has proven unproductive. With no tolerance for experimentation, there is no room for innovation or learning. Even if unproductive, staying comfortably inside the box is safe.

Efforts to introduce a “whole of government” approach to deal with complex challenges like climate change or persistent poverty have had little effect to date. However, Canada’s federal system does allow for different approaches to be tried in different parts of the country and some jurisdictions have been able to introduce quite bold new policies and programs. Quebec’s approach to youth offenders and publicly-funded daycare, for example, is very different from that of the federal government or other provinces.

Changes in the market and new opportunities—often the result of new technologies –drive economic progress. Social organizations are slower to adapt since their revenues are less sensitive to changes in demand, need, and performance, and their market is often seen to be their funders rather than the constituencies or causes they serve. Funding models are based on avoiding risk rather than experimenting with new approaches that might increase effectiveness. Fresh ideas emerge through the creation of new organizations, but they enter a crowded marketplace and are often unable to demonstrate convincingly their superior efficacy. For established organizations, technological innovation is frequently viewed more as a problem than as a source of creativity.

The Community Sector Today

We don’t have to change the world; the world is changing. We have to change ourselves.

In exploring how these changes may affect the community sector, we need to distinguish between different types of organizations, with different missions and revenue models. “Community sector” (or voluntary sector) is an imprecise term that includes organizations that deliver services (often funded almost entirely by governments), religious groups, voluntary associations, and interest groups. For our purposes, we will limit our consideration to formal bodies that are officially registered charities of the “core” sector (that is, excluding municipalities, universities, colleges, and hospitals), while recognizing that community also embraces informal networks and associations, and virtual as well as face-to-face relationships.

The lifeblood of the sector is the willing contribution of time and money provided by individual Canadians. Levels of giving and volunteering in this country are often compared to those in the United States. Americans expect less of their governments and are correspondingly more generous in supporting what they call the Independent Sector, whereas Canadians have tended to accept a higher level of taxation in exchange for greater social spending and some income redistribution. This may change in the future in the face of declines in both government revenues and services.

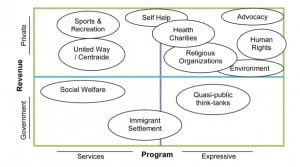

The main drivers of change for community sector organizations will be demographics and technology, and, of course, cuts to government grants and contributions. The relative importance of each will vary according an organization’s mission and main revenue sources. If we were to present this schematically it might look like the following, with source of funding (public or private) along one axis and nature of activity (program or service and advocacy or, “expressive,” along the other).

Organizations that are heavily funded by governments to deliver services are inevitably most impacted by public spending cuts or policy changes. Think tanks that receive government funding, like Rights and Democracy, established by Act of Parliament, or the North-South Institute may be especially vulnerable.

Early in December 2009 the Globe and Mail ran a banner headline “The price of stimulus: Here come the cuts.”8 With a deficit projected at some $60 billion this year, and recurring deficits running for at least the next several years, it is clear that these organizations face a long period of stagnant or declining revenues. Commentators have remarked on the unreality of the federal government’s claim that economic growth alone will tame the deficit. In the 1990s growth in population and the labour force swelled tax revenues, but this is no longer the case.

“Belt-tightening has its limits and at some point starts to damage vital organs.”

Lester Salamon, Johns Hopkins University Centre for Civil Society Studies

We have been here before. During the 1990s government funding was drastically cut; organizations coped by eliminating programs, reducing staff and by the timehonoured method of “doing more with less.” The price was high, and one result was a belated recognition on the part of the federal government that it had inadvertently brought the community sector almost to its knees. The resultant Voluntary Sector Initiative launched by the Chrétien government in 1999 was an attempt to alleviate the impact by negotiating a new relationship based on mutual respect and support, including agreed-upon conditions for financing. Almost nothing of long-term value resulted from this and although it culminated in a so-called ‘Accord between the Voluntary Sector and the Government of Canada’, both the Liberal and Conservative governments that followed have mostly ignored it.

A more diverse population will also affect the sector. Volunteering and donating, as expressions of civic-mindedness, are deeply shaped by culture and appear to be shifting as people’s view of government’s role and of citizenship evolve. A growing rural-urban gap may also limit government’s ability to ensure health and other services in sparsely populated regions, which will increase the demands on the community sector. However, the notion that cuts in government services such as assisted transport or home care support or remedial education will be offset by community organizations, unless there are deliberate measures to increase their capacity, is simply fanciful.

Historically in Canada even organizations in the other quadrants of the diagram, ones largely reliant on donations and volunteer time, have received some government support (as well as, of course, tax incentives for donors). However, they are less likely to be affected by public spending cuts, though trends in volunteering will have an effect, as will the opportunities opened up by new technology.

Let us look at the current business model in terms of revenue streams, human resources, and organizational structure.9 Generalizations are suspect given the extreme diversity of the sector, but the following attempts to give a broad overview for analytical purposes.

1. Money

Although we think of the voluntary sector as being primarily funded by charitable donations, this is not the case. Excluding hospitals, universities, and colleges, 43% of its revenue is earned from the sale of products, memberships, and fees-for-service, whereas 36% comes as grants and contributions from government (and two-thirds of that from provincial governments), and only 11% from individual donors.

Organizations that depend mostly on grants and contributions from the federal and provincial governments, the bottom half of the diagram above, are most vulnerable to cuts in public funding (that applies especially to bodies pursuing causes like human rights and global development, such as the Canadian Council for International Cooperation or the North-South Institute). How are organizations supported mainly by individual donors faring? A superficial look at their financial position is reassuring. Overall, donations have grown year over year—although in 2008 the amount donated by Canadian tax filers fell by 5.3% (to a total of $8.1 billion10 ). But this obscures a reality that people in the sector know all too well: increasing competition for an inadequate pool of funds, too many restrictions on how grants and donations can be used, and a short-term focus that makes investment in future effectiveness nearly impossible.

For some time there has been a long-term trend toward fewer, larger donations. Many United Way/Centraides, for example, have seen their annual campaign totals rise year by year, while the number of donors falls. For the period 2000-2005, the average size of receipted donations to all charities has gone from under $1000 to almost $1400, but the number of taxpayers claiming these deductions has dropped by several percentage points. The pattern of a shrinking donor base is masked by the larger gifts, with only 9% of donors responsible for fully 62% of donated dollars. Larger individual gifts may also be directed disproportionately to hospitals, cultural institutions, and universities, accelerated by the federal tax changes in 2006 that made gifts of appreciated shares more attractive.

Donations may only contribute some 11% of charities’ revenue, but their value lies in their being (mostly) unrestricted, unlike most of the money provided by governments, foundations, and corporate donors. This source therefore underwrites much of the operational costs of organizations in the sector; worse, it often subsidizes the other funding sources. Historically, as Lynn Eakin’s studies have shown,11 governments have received a hidden subsidy of some 14% to the programs they support. Increasingly onerous accountability requirements, the emphasis on “value for money” in the narrowest beancounting sense, and even the cost of open bidding processes involving the private sector, increase the administrative burden. To rub salt in the wound, agencies are then assessed by some charity watchdogs according to the proportion of their “overhead” to overall expenditure as if it were axiomatic that lower management costs equal greater efficiency.

When surveyed on their financial needs, the answer of community organizations is overwhelmingly “more support for core costs.” The response of many funders has been instead to direct grants to “capacity-building.” Such grants have not generally been successful, though there are cases where recipient organizations have been able to make good use of them. It could be argued that they have a perverse effect when managers are unable to invest in organizational development and long-term planning due to lack of core funding, so donors step in to determine what needs to be strengthened through capacity-building grants. The result is that leaders and their organizations cannot be fairly assessed on their management abilities and operational results, since in a sense donors have refused to give them the means to manage properly.

The disconnect between the demand for organizational effectiveness and the disinclination to support core costs comes down to a matter of trust. Tying funding to specific time-limited projects appears to reduce the risk to donors, but loading recipients with reporting and other requirements and refusing to provide unrestricted support actually prevents them from investing in the human and organizational infrastructure that could enhance their effectiveness. There is a legitimate concern about minimizing dependence on a particular donor, but lack of core funding actually makes it harder for an organization to explore alternatives or to create a sustainable base for its work. The answer to a lack of trust is to pursue greater transparency and candour, not to dole out targeted, tightly controlled grants, as well as to continue to develop generally accepted metrics such as the Social Return on Investment (SROI).

In effect, if we were to compare the financial tools available to community organizations with those available to for-profit firms, they are limited to seed capital in the form of philanthropic support and grants, with almost no working capital or venture financing. The exception to this has been so-called venture philanthropy, often led by successful business people who approach charities as they would potential investments. They expect their ‘strategically targeted’ donations to solve problems, not merely alleviate them. They are willing to invest significantly in organizational capacity—but often, in the process, they too encroach on the autonomy and responsibility of recipient organizations.

In short, the “ideal” of charities receiving stable funding from a broad base of donors is no longer accurate, if it ever was. Instead, there is a mix of self-generated revenues (sometimes contested by private sector firms decrying “unfair competition” by untaxed charities) along with uncertain project-based and short-term government support that often comes with onerous conditions and high transaction costs.

In the medium term, the inadequacy of this response will become even more painfully evident. Today’s economic conditions have helped to create the “perfect storm” of growing demands on community agencies, cost-cutting by governments as they go deeper into deficit, and stagnant or declining donations by cash-strapped individuals, foundations, and corporations.

2. People

In terms of human resources, community organizations are unique in that they rely on both paid and unpaid staff.12 The community sector, excluding hospitals, universities and colleges, has 1.2 million full-time employees13 and a further 525,000 FTE volunteers, which together amount to almost 10% of Canada’s economically active population. Historically, the community sector pays less than ‘market wages’ to most of its fulltime employees. The sometimes dramatic gap is said to be justified by the psychic or nonmonetary rewards afforded by the work, or by the high level of motivation and commitment demonstrated by many who work in the sector. In a recent survey by the HR Council for the Voluntary & Non-profit Sector, an impressive 96% of respondents said, “I am committed to my organization.”

Organizations are beginning nevertheless to experience difficulty attracting and retaining staff. The lack of job security due to irregular and short-term project funding, limited opportunities for advancement within organizations, long hours (usually unpaid), and sometimes poor personnel practices, are cited as reasons for this difficulty. Surveys of younger employees and job-seekers also suggest that expectations are changing; entrants into the labour market want a better balance between work and personal lives, which is at odds with the ethos of selfless service that permeates many charities. In the same HR Council Survey, nearly half of employers who tried to recruit staff in the past year said it was “difficult” or “very difficult.” Organizations are not only having difficulty recruiting young staff, they are not reflecting the diversity of Canada’s population. Almost 90% of the people working in the sector identify themselves as white or Caucasian, and only 2.5% as members of an ethnic minority (whereas the number of Canadians belonging to ethnic minorities is projected by Statscan to double by 2017). There is still a lingering hangover from the charity mentality of helping others (many youth-serving agencies, for example, are staffed exclusively by adults, with little room for young people to take on real leadership roles). Only in the past few years have we begun to see charitable organizations dedicated to serving people with disabilities or immigrants or people living in poverty actively seeking to recruit staff from those communities. The group of activities run by the Maytree Foundation’s Diverse City program in Toronto,14 for example, addresses this by providing training, contacts and networks of support for people from minority groups who want to become actively engaged in local political and social development work benefitting the wider community.

The high numbers of Canadians who volunteer is testimony to civic-mindedness. However, a ten-year trend demonstrates a gradual but undeniable weakening of this public spirit. A small minority is responsible for most of the time devoted to volunteer work: only 11% of Canadians account for fully 77% of the volunteer hours. Not surprisingly, the bulk of this effort goes to organizations that deliver services—food banks, meals-onwheels, hospital auxiliaries, and the like—with another 25% devoted to what StatsCan terms “expressive” activities—promoting causes like human rights and environmental conservation. The growing difficulty in recruiting volunteers is due not just to time pressures, greater job mobility, and perhaps less socialization into volunteering through church attendance and parental example, but also to the requirement for security checks and concerns about the potential legal liability of not-for-profit board members. Smaller organizations are particularly hard hit since almost 75% of all volunteers are engaged by only 6% of charities, representing the largest organizations. Furthermore, the nature of volunteering is shifting—away from long-term commitments toward more episodic involvement, with greater attention to “what is in this for me?”

The classic image of the volunteer is the person who fits in, uncomplainingly doing what needs to be done. Since they may be viewed as free labour, they receive little attention and the value of their work to the organization is rarely rigorously measured. Volunteers who drop out consistently give as their reasons a failure to use their skills effectively or to recognize their contributions, lack of training and support, and the absence of strong leadership. Not surprisingly, there is high turnover; the volunteer experience proves to be as unfulfilling for the individual as for the organization, justifying further neglect of this important resource.

Research conducted recently by Framework Foundation reveals that of 197 courses offered by Canadian post-secondary institutions on voluntary sector management, only 22% (according to the course descriptions) address human resource issues like engaging, training, and managing staff and volunteers. On the other hand, one-third deal with fundraising and financial management.15 More attention needs to be directed to how the community sector engages and trains a new generation of volunteers who have different and more demanding expectations but also much to contribute.

The combination of pressure to improve salaries for paid staff, in order to attract and retain people with the skills that this demanding work requires, and the slow but steady erosion of the civic core of volunteers, suggests that the human resource profile of the community sector will have to change significantly. Furthermore, as we have been reminded over and over, organizations will have to become more diverse in their staffing, boards, and volunteers, if they are to reflect Canada’s people.

3. Structure

The difficulty of starting and maintaining a community organization cannot be underestimated. There is very little “risk capital” available and almost no tolerance for failure (defined as inability to produce the desired results in the planned timeframe). It has often been observed that given those limitations, very few business start-ups would succeed. For donors of all kinds, too often a lack of results is viewed as evidence of incompetence or mismanagement, not the inevitable consequence of exploring and testing new approaches in the search for greater effectiveness.

A feature that distinguishes community organizations from business is the absence of meaningful outcome measures. Consequently, very few established organizations go out of business. Renewal through “creative destruction” rarely takes place, leaving observers to comment on the apparently inexorable growth in the number of organizations and the consequent increase in competition for attention and public support. However, as donors target their contributions to specific projects or programs, it is becoming increasingly difficult to meet essential operational costs, forcing some organizations to chase grants or undermining their ability to manage properly the program funding they receive.

In sum, the current business model is characterized by serious and growing weaknesses in its financial and human resources, chronic underinvestment in staff development and management systems, including technology, and a culture that discourages risk-taking and innovation.

The community sector tomorrow?

Today you cannot even do good unless you are prepared to exert your share of power, take your share of responsibility, make your share of mistakes, and assume your share of risks.

George Kennan, quoted in Joshua Cooper Ramo, The Age of the Unthinkable, 2009

It would be presumptuous to define a new business model for all community sector organizations, so what follows should be considered suggestive rather than prescriptive.

But in facing the changes that have been described (and many others) it is important to bear in mind that the default is not to business-as-usual. Cyclical change can perhaps be handled by stop-gap measures and belt-tightening until things return to “normal.” Structural change needs organizational resilience and a clear-eyed ability to distinguish between what must be held onto and what must be re-invented. And disruptive change is best dealt with, as we shall see below, by embracing innovation.

Recognizing the growing strains experienced by the charitable and community sector in financing its activities, an initiative was started in 2002 to create a new financial institution that would serve the charitable and not-for-profit sectors in Canada. Called Vartana, it was inspired by similar models in the U.K. and Europe, such as Triodos and the Charity Bank. Ultimately the initial idea of a standalone bank proved not to be viable. Vartana entered into a partnership with Citizens’ Bank, a subsidiary of B.C.’s Vancity Credit Union, but the financial crisis of 2008 caused Vancity to wind up Citizens’ Bank’s retail operations and Vartana died.

1. Money

Many voices are arguing that now is the time to jettison the old funding paradigm based on government grants and contributions augmented by private donations. In this view,16 traditional fundraising should be replaced by an integrated (and entrepreneurial) approach to financing all of an organization’s needs, including programs, infrastructure and investment in future development. Instead of being treated as a separate activity assigned to the fundraiser(s), who is usually separated from the content of an organization’s work, financing is treated as a core activity of the organization, incorporating other types of capital (loans, equity) as well as donations, grants,

gifts-in-kind, and voluntary labour. Earned income is one possibility, though obviously not one that is appropriate for every organization.

Organizations that deliver services and that are largely funded by governments will need to be highly professional, competitive, and efficient. They will need solid evidence of the superior efficacy, not just lower costs, of their work in order to negotiate contracts with governments that fully cover all of their costs, including a provision for R&D. On the other hand, cause or expressive organizations will diversify their funding and take full advantage of the range of ways that new interactive technologies engage donors.

In 2007 a group of individuals and organizations formed Causeway,17 a collaborative effort to promote the creation of a social finance marketplace in Canada. Annual conferences, policy research, study trips, and an outreach strategy have helped develop understanding of ways that new and more diverse financing strategies could free the community sector from its crippling dependence on government and donations.

In Quebec, the social economy, comprising credit unions, community economic development organizations, social enterprises, co-ops and other not-for-profits, has long enjoyed a level of official recognition and support that the rest of the country can only envy. With $17 billion in economic activity, it is 6% of the provincial economy. In 2004, the Martin government responded to intense lobbying by introducing a $132 million funding package to support the social economy through research, capacity-building and financing. Only Quebec was sufficiently prepared and able to take advantage of the financing before it was withdrawn by the newly elected Conservative government. The Fiducie, managed by the Chantier de l’economie sociale, now has a fund of some $60 million to invest in social enterprises in Quebec (and in 2006 earned a 7% return). In Ontario, B.C. and other provinces, creation of Social Capital Venture funds is being considered, while private investment is coming from Vancity Credit Union, Social

Venture Partners, and others.

An entrepreneurial approach to funding is sometimes interpreted to mean that not-forprofits should act like commercial enterprises. The notion that community organizations should operate “more like businesses” is hotly contested. Jim Collins in Good to Great and the Social Sectors criticizes the assumption that business tools can be applied uncritically in social sector organizations, pointing out that discipline, efficiency, and a focus on results characterize high performing organizations in any field.18 A lively debate has taken place around what has been called “philanthrocapitalism,” with some exalting the new energy injected into the social sector by the likes of former President Clinton, Jeff Skoll, and Pierre and Pam Omidyar, who use the market to pursue social goals through both social enterprises and for-profit corporations.

On the other side of this debate, critics like Michael Edwards argue that business thinking shifts the focus away from the need for deep-rooted structural reforms to eradicate poverty and other social ills, warning that it can lead to “an inappropriate bottom line, and lead us to ignore the costs and trade-offs involved in extending market mechanisms into the social world.”19 Edwards goes on to say that transformative change will flow from “social movements, politics and government,” all usually ignored by organizations trying to play by for-profit rules.

But is the contrast between social activists and social entrepreneurs overdrawn? First, the notion that all community or social sector organizations should attempt to be selffinancing is clearly unrealistic. Organizations that have the mandate to deliver services, especially to vulnerable and poorly-served people, will continue to need government grants and private donations. On the other hand, we have many examples of social activists making creative use of market mechanisms to effect real change, particularly affecting the environment. Nicole Rycroft of Canopy (formerly the Markets Initiative) is one example: over ten years Canopy has encouraged over 650 publishers, magazines, and newspapers to use sustainably harvested wood pulp, thereby saving some 18 million hectares of forest, including many valuable ancient forest lands. Other organizations have targeted endangered species, unhealthy foods, and tobacco use, mobilizing consumers to force changes in corporate practices, sourcing, and labour policies.

The issue of funding of community sector organizations cannot be separated from that of evaluation. Because there is no generally accepted bottom line, funding ends up based not on performance and effectiveness but on what Jed Emerson calls “the schmooze factor”—politics, perception, and persuasion. Simple but misleading indicators, such as low overhead costs, reflect the lack of objective standards of measurement and become a proxy for efficiency.

Unfortunately, and paradoxically, evaluation is seen to be both important and, as currently practiced, frequently unhelpful. Too often evaluations focus on the program or grant but ignore the health of the implementing organization; they are used to provide cover for grant-makers (summative evaluations that are too lengthy or academic to be of practical use); or they seize on “hard” data, usually inputs, and miss the larger picture- the results. Some of these weaknesses are being corrected now, with more emphasis on learning, quicker feedback loops, and greater acceptance of the value of qualitative data to give meaning to numbers.

Much effort is now being devoted, only partly due to the prodding of the “venture philanthropists,” to establishing common standards to assess results, including social return on investment (SROI),20 or methodologies suited to programs tackling complex social challenges, such as developmental evaluation.21 However, even the strongest proponents of SROI concede that it is expensive and time-consuming. More immediately promising is the use of comparative assessments, such as cluster evaluations that explore results obtained using different approaches or evaluating funder practices relative to other funders. There is also a proliferation of external monitoring groups like Guidestar, which claim to provide objective information to donors.

Sheherazade Hirji emphasizes the importance of evaluative thinking rather than focusing only on methods and measurements. She quotes Michael Quinn Patton: “Evaluative thinking includes a willingness to do reality testing, to ask the question: how do we know what we think that we know. To use data to inform decisions—not to make data the only basis for decisions—but to bring data to bear on decisions. Evaluative thinking… is not just limited to formal evaluation. It’s an analytical way of thinking that infuses everything that goes on.”

The U.K. has developed the concept of social impact bonds, into which donors can invest but whose payout depends upon agreed-upon performance targets, which underlines the importance of unambiguous metrics. An example would be an organization rehabilitating people with addictions, which would attract the necessary financing to run its programs based on a target of x% success rate. Those that failed would go out of business, while successful programs would attract more money. The standard of measurement is not overheads or good public relations, but results. Of course, only certain kinds of programs would be suitable for such bonds.

2. People

Who will constitute the workforce for the new community sector? Again, generalizations obscure as much as they clarify. Specialized agencies dealing with health, the environment, and the arts will continue to require professional management (while depending upon volunteers for many functions). Others, including religious bodies, sports and advocacy or expressive organizations may be able to rely more on unpaid staff. The crucial shift will be in the nature of the distinction between paid and unpaid staff: in the future, both categories will be considered to be equally important parts of an organization’s human resources and will receive equal management and attention. The present practice of using volunteers to carry out routine or low priority tasks that paid staff do not have time or inclination for will be supplanted by an approach that tailors assignments to volunteers’ interests and skills. Paid staff will fill the gaps and ensure a balance between institutional needs and volunteers’ fulfillment. In other words, instead of using volunteers to meet organizational needs, work will be configured also to address participants’ personal needs. This may sound like more Boomer self-indulgence; in fact, it simply recognizes the fact that people today are less motivated by loyalty to an organization than by commitment to a cause and by a desire that their contribution be meaningful.

Montreal-based Santropol Roulant already offers an example of this. It evolved from a youth-run Meals-on-Wheels program to an inter-generational community hub that engages large numbers of (mostly) young volunteers to provide services while at the same time creating a sense of belonging and participation that acts as a magnet to constantly replenish the volunteer pool.22

The two most promising sources of unpaid workers are the young and the retired. The young are looking for experience and a congenial work environment; the retired want to remain active contributors, using their knowledge and skills to enhance their communities. Both young and old want to feel they matter, that they are not just treated as cheap labour. Smart managers will integrate them into planning and organizing, not just carrying out tasks set by others, and find ways to sustain and stimulate their commitment to the organization and its mission. United Ways-Centraides, which depend on volunteer fundraisers and large donors, organize orientation programs that enable campaign leaders and major contributors to meet and interact with the people relying on United Way support. Organizations like the Quebec Red Cross, which has a provincial mandate to plan and implement emergency response actions, carry out intensive training programs and develop skills that have value for both the individual and the organization.

Fortunately, new information and communication technology makes training and access to operational systems easy and cheap, so that integrating and orienting new volunteers can be a permanent activity.

3. Structure

Changes in revenue models and staffing patterns will open up new institutional forms as well. Boundaries between for-profit and not-for-profit will continue to blur along a continuum that ranges from traditional for-profit firms engaged in public benefit activities at one end, through various types of “blended value” enterprises to charities at the other end. Many young people seem to be less concerned with legal structure than with efficacy: what works? If a proposed mission requires access to significant capital, then a not-for-profit or even commercial corporate structure may be more efficient than a charity. Until now, motivation differentiated community organizations from businesses; now the goal remains public benefit, not personal enrichment, but the financial model may be determined more by the source of financing.

The United Kingdom and the U.S. have moved much further in creating flexible legal frameworks to facilitate the development of blended-value enterprises, which generate both a social and a financial return. Community interest companies (CICs) were introduced in Britain in 2005. They operate like businesses but must demonstrate that they create a community benefit; they may issue shares to raise capital but there is a cap on returns and an “asset lock,” which means that profits and assets must be retained by the community, not distributed to shareholders. By the end of 2009, some 3,300 CICs had been set up23 and were doing business in fields such as low-cost housing, home support, recycling, etc. Community development venture funds, initially a partnership between government and the private sector and now wholly private, provide investment capital, while other institutions provide advice, mentoring, and professional services to budding social entrepreneurs and enterprises.

A similar development in the U.S. has led to the creation of new entities called low-profit limited liability companies, or L3Cs, by several states. Like CICs, they can raise private capital by issuing shares or through other financial means, and their purpose is to use market mechanisms to meet community needs. One important consequence is to open up opportunities for U.S. foundations to make program-related investments (PRIs), using their assets rather than just their grants to fund community needs.

Organizations like the B.C. Centre for Social Enterprise24 and Causeway are encouraging policymakers and community groups to explore how structures like CICs could help community organizations here to tap into new sources of capital. What is striking at this stage is how quickly other jurisdictions are moving to address a problem that is still mostly overlooked in Canada.25 The goal is not to enshrine a new organizational form per se but simply to broaden the range of options available to social entrepreneurs.

Technology extends reach and lowers costs, even as it calls for a new set of skills. As Clay Shirkey, who writes, teaches, and consults on the social and economic effects of the Internet, puts it, “Most of the barriers to group action have collapsed, and without those barriers we are free to explore new ways of gathering together and getting things done.”26 The implications for community organizations are far-reaching and as yet little understood. Where previously an individual or group would start with an idea or cause and then create an organization to raise money and manage the financial and human resources needed to reach the objective, this can now be done by loosely coordinated groups with little or no formal structure, overheads, or centralized control. Organizations like Taking IT Global, based in Toronto but with members around the world, are facilitating this process now but already it is happening spontaneously through the use of social networking sites like Facebook, empowering people who would never have been able to communicate and organize in the traditional way. Framework Foundation, which launched the Timeraiser concept as a way to engage young people in volunteering, is using suites of open-access Internet tools to manage its national program, such as those offered by Techsoup and the social tech training program at MaRS.

Fundraising is being transformed by donation portals like CanadaHelps or direct giving sites such as Kiva for small loans to entrepreneurs overseas, and DonorsChoose brings together donors and teachers in the neediest U.S. public schools. This has enormous implications for charitable organizations, which must hone their communication capacities and demonstrate their own value-added to donors who may feel they can dispense with intermediaries in favour of virtual person-to-person relationships. It poses a challenge for donors and regulators too: what new forms of accountability are needed where there are no top-down formal structures? Tax incentives for giving (which rank low in surveys of motivations for donating to charities anyway) become even less important where action precedes structure.

Universal access to information weakens the “gatekeeper” role of professional staff, who no longer have the principal influence in analyzing needs and setting priorities. Indeed, solutions can be crowd-sourced, as entrepreneur Richard Branson and others27 are doing by offering financial incentives for solutions to global challenges. Toronto’s Treehouse Group, along with others, is exploring this on a more local basis, convening ‘unexpected’ gatherings of citizens to brainstorm on social, environmental, and other issues.

New technologies and social process tools permit us to talk about a new operating system for the social sector. This could include:

• Common social impact metrics and reporting platforms that enable funders and grantees to speak the same language when it comes to application, measurement, and reporting. No more “drowning in paperwork, distracted from purpose.”

• Shared collaboration platforms, so that multiple funders, grantees, academics, and policy makers can track interventions and share learning around particular issues. This replaces the duplication, secrecy, and unhelpful competition that slow progress. The growing ability to gather and analyze data across sectors portends yet another wave of change.

• Like crowd sourcing, Change Camps—developed by Toronto’s Mark Kuznicki

– use Open Space technology to bring together ordinary citizens with bureaucrats and technical experts. The process can be used to design improvements for everything from transit systems to health clinics.

• Back-office collaboration, such as offered by TIDES Canada, which lowers the cost of start-ups and creates multiple efficiencies.

nexts te p s

Social Innovation

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.

Charles Darwin

It has been said that there’s nothing new about innovation. But until recently it was seen almost exclusively as resulting from scientific or technological discovery or invention, usually taking place in university labs or corporate R&D departments. The concept of social innovation has emerged more recently. It has been defined most simply by the Young Foundation’s Geoff Mulgan, a prolific writer on the topic, as “new things that work.”28

Frances Westley defines it as “a complex process of introducing products, processes or programs that profoundly change the basic routines, resources and authority flows or beliefs of the social system in which they arise.”29 The answer to the question Why social innovation? must be either because traditional efforts to solve complex problems like poverty, adequate housing or addiction have been ineffective, or because changed circumstances call for new understandings and approaches. However, nothing would be more unhelpful than to treat social innovation as a panacea that can by itself solve all social problems.

The term may be relatively new but there have always been visionaries and pioneers adopting novel ways to meet social challenges. The hospice movement, the Open University in the U.K., food banks, “designated drivers,” and innumerable other examples demonstrate that ingenuity is a constantly replenished resource. Nor are all social innovations necessarily new; in some cases, they may involve reworking old ideas to new purposes or re-framing a problem so that fresh solutions surface. Not surprisingly, our early understanding was strongly influenced by the linear industrial model: discover, market test, commercialize, then scale up as rapidly as possible. Ashoka, founded in

1980, has done much to popularize the notion of the social entrepreneur as visionary leader, but social innovation should not be confounded with entrepreneurship in the business world. Apart from the structural obstacles faced by not-for-profits (lack of venture capital, risk aversion of funders, short time frames to demonstrate results, etc), their end goal is not simply scale but impact.

The greater challenge now is not to generate new ideas per se but to create systemic supports for a continual process of social innovation in Canada: identifying promising initiatives, rigorously testing their efficacy, and then investing in those that demonstrate results so that they have real impact. This may be contrasted with the present situation, which has been aptly described as “letting a thousand flowers wither.” Necessity may indeed be the mother of invention, but too often the offspring has been orphaned by lack of patient capital, advice, mentoring, and other help.

The example of Vancouver’s PLAN is instructive: from a limited local role directly supporting families of children with a disability, it developed a policy and advocacy capacity (which resulted in the federal Registered Disability Savings Plan in 2009), and then a financial/advisory function to help banks design suitable products and to ensure the RDSP would be widely available and its benefits not clawed back by provincial regulations. PLAN could not have achieved its goal of systemic change benefitting hundreds of thousands of Canadians without vision, strategy, and the ability to collaborate with government and financial institutions.

The U.K. offers an example of what such systemic support might look like. When Tony Blair and New Labour came to power in 1999, they concluded that the economic and social challenges facing Britain could not be solved by government or the private or the community sector alone. A collaborative approach was needed, which required large-scale investment in the capacity of the community or “Third Sector” in particular. Investment funds to support social enterprises (Bridges Ventures), loans and equity for charities (Venturesome), access to business advice (UnLtd.), and office and infrastructure support (The Hub) all contribute to creating an environment that supports budding social innovators. New Zealand and Australia are moving in a similar direction, and in the U.S. one of the first acts of the new Obama administration was to create the White House Office of Social Innovation with a US$50 million Innovation Fund to encourage and support new approaches to solving social problems.

The need is no less pressing in Canada, where issues such as the transition to a “green” economy, a less energy-intensive lifestyle, or solutions to aboriginal poverty cry out for fresh thinking. In Britain, the goal of partnership led to the creation of the Office of the Third Sector within the Prime Minister’s Office to ensure that community concerns and viewpoints are taken into account at the highest level of decision-making. This recognizes that innovation usually occurs at the margins and at the frontlines where community activists and ordinary citizens are struggling with real problems and demonstrating great creativity and resourcefulness. As Henry Mintzberg has written, “Organizations learn their way into interesting strategies through small ventures that arise from the initiatives of all sorts of people.”30 What is typically lacking is a link between those promising initiatives and policy-makers so that ideas that have proven their value can be widely disseminated, and policy, in turn, can reflect good practice and facilitate further improvement. As in business, in which many small ventures are launched but only a few will turn out to be worthwhile, the goal must be to leverage those that prove their worth to create truly transformative change.

Social innovation is a subject of growing interest in Canada. Universities like Waterloo, Carleton, and UBC have developed programs; many others, including York, Victoria, Concordia, and UQAM, link academic research to community needs through knowledge-transfer offices; dozens of others have launched service-learning initiatives that encourage students to contribute what they are learning to community organizations with the goal of mutual benefit.31 The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council is strongly encouraging such collaboration through its Community-University Research Alliance (CURA) grants.

Provincial governments in Ontario and B.C. are taking an active interest. What is lacking is overall leadership such as that provided by former Prime Minister Blair or President Obama. In Canada, the community sector’s relationship at the federal level is with the Canada Revenue Agency, which is charged with regulation of charities but whose mandate is tax collection.32 Until and unless the community sector is accorded a more central place in government thinking, there will be little attention and less support to facilitating its contribution to improving Canadians’ well-being.

Canada’s community sector contains many highly innovative organizations and individuals. But the price they pay in frustration, staff burnout, initiatives curtailed before they can demonstrate proof of concept, etc. is unacceptably high. We need to encourage enterprising individuals and risk-taking organizations, but we also need to put in place systemic supports such as exist in the U.K., the U.S., and other countries.

One step in this direction is Social Innovation Generation (SiG), a cross-sectoral collaboration, involving the University of Waterloo, the MaRS Discovery District in Toronto, Vancouver-based PLAN Institute, and The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation. SiG’s goal is to be a catalyst bringing together academic, business, government, and community sector people and organizations to strengthen social innovation in Canada.33

Ten characteristics of highly innovative organizations

1. Innovative organizations are uncompromising on their goals but flexible in their methods; they are service deliverers working to change policy and advocacy organizations developing programs on the ground. The only question is “what will get the job done?”

2. Innovative organizations are focused on achieving change at scale. This means that they are adept at working at multiple levels, scaling up local actions to effect system-level change. The key measure of success is impact.

3. Innovative organizations have an entrepreneurial mindset, seizing opportunities and harnessing the power of markets to achieve their goals.

4. Innovative organizations implement change strategies that are disruptive; they challenge existing business models and prevailing wisdom.

5. Innovative organizations are collaborative, sharing credit for results and ensuring that the lessons of both success and failure are widely disseminated.

6. Innovative organizations are mavens, understanding the power of networks and thought leadership. Catalyzing change is less about the quantitative size of organizations (staff, budgets, programs) and more about strategic influence that proactively changes the context in which change is being pursued.

7. Innovative organizations are systematic and intentional in how they embed and sustain an internal culture of innovation.

8. Innovative organizations are inclusive, recognizing that all the organization’s members, including clients and other stakeholders, should be involved in the innovation process.

9. Innovative organizations are tech literate, embracing new technology and open architecture for the innovation process.

10.Innovative organizations are experimental, understanding that remarkable innovations are less a spark of lightning and more the culmination of a thoughtful iterative process of continuous beta testing and on-going refinement of ideas

Collaboration

Most sustainable improvements in community occur when citizens discover their own power to act…when citizens stop waiting for professionals or elected leadership to do something, and decide they can reclaim what they have delegated to others.

Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging, 2008

For almost ten years, a community of practice has supported the work of almost two dozen social innovators funded in part by the McConnell Foundation.34 In fields as disparate as education, health, and child welfare, practitioners have met to exchange ideas, learn from each other about the process of “applied dissemination,” and learn how to leverage their programs to transform systems.35

An African proverb says, “If you want to walk fast, walk alone. If you want to walk far, walk together.” Our tough social challenges increasingly require us to walk fast and far and together. How can we support the deliberate practice of collective walking in such complex contexts? By carefully constructing a container within which a team can address the tough social challenges that they all want to resolve but that none of them can resolve alone…a physical, social, mental, and intentional place.”

Adam Kahane, Power and Love, A Theory and Practice of Social Change, 2009

Participants have frequently remarked on the value of these opportunities for peer learning. The old competitive mind-set of organizations, the struggle of ‘all against all’ for resources and recognition, is changing. It was noteworthy that when the major national environmental organizations (dubbed the Strathmere group) issued a common position paper before the last federal election in 2008, what commanded media attention was precisely the fact that it was the first time all had agreed on a consensus statement.

Equally challenging is working cross-sectorally (with what the book Getting to Maybe calls “strange bedfellows”). The Toronto City Summit Alliance is a model for how the commitment of all sectors of the community can be harnessed to attack a common agenda. One of its projects, sponsored by the Maytree Foundation in collaboration with business and civic leaders, is the Toronto Regional Immigrant Employment Council (TRIEC), which in turn has inspired a national network of similar programs to facilitate suitable jobs for professionally qualified new Canadians.36 Another example of cross-sectoral collaboration is Vibrant Communities, a thirteen-city poverty eradication program based on a shared commitment by local business leaders, municipal officials, service organizations, and people living in poverty to work together on strategies to move people sustainably out of poverty. In Hamilton, Saint John, Waterloo Region, Calgary, the Saint Michel neighbourhood of Montreal, and other cities, these dynamic, locally-led, comprehensive initiatives are not waiting for politicians to lead; they are creating their own leadership by building consensus and a conviction that change is possible.

In Waterloo Region, Communitech, a dynamic network of local business leaders, has recognized the value of a vibrant community sector and launched Capacity Waterloo Region to invest in community organizations, with a particular focus on innovation to meet local needs. A similar process is underway in Calgary37 and doubtless in other communities as well.

What these efforts have in common is the willingness of people from different sectors to set aside differences to achieve a common objective, a recognition that collaboration is a prerequisite for success. The environmentalist Paul Hawken put it this way: “Do what needs to be done, and check to see if it was impossible only after you are done.”38

There is a looming public policy question facing Canadians: how do we maintain public services when needs outstrip government revenues? So far we have dodged this by putting today ahead of tomorrow, in other words by cutting our taxes, giving priority to health care for this generation over education for the next, postponing dealing with climate change and conservation, and shifting fresh burdens onto weakened family structures and an overstretched community sector. Just to take health care as an example, we know that an aging population makes more demands on the system: at $183 billion in 2009, it already represents 11.9% of GDP and has been rising at 4-5% over the rate of inflation for the past decade. A person between 1-64 years costs the health system some $3,089 per annum; by age 75 that rises to $10,000, and by age 80, to $17,000 each year. The economic burden of dementia alone is projected to go from $15 billion in 2008 to some $153 billion in 2038.39

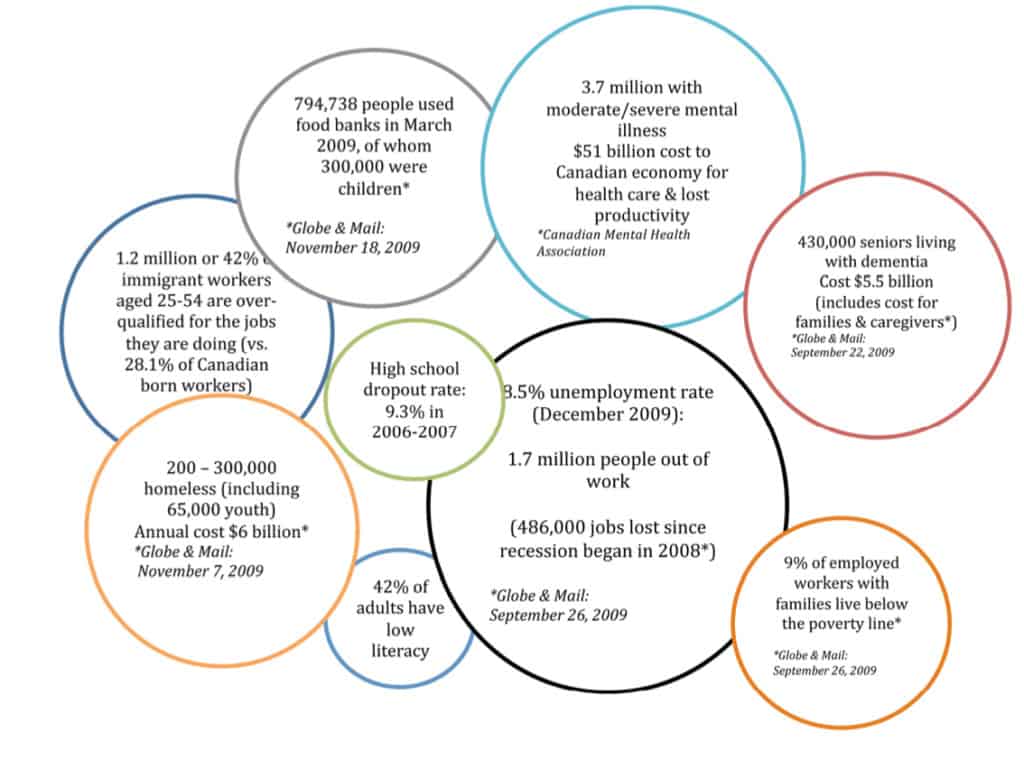

Canada has a broad system of supports for people we deem “marginal”—the unemployed or unskilled, people with mental illnesses or with various forms of physical or intellectual disability, etc. As a relatively affluent country, we accept the cost as the price of having a humane society in which no one is left in absolute want. Over time, it has evolved into a significant “benefits economy” into which substantial numbers of people (see chart) who are labeled disadvantaged, vulnerable, at risk, et cetera are consigned, and then treated no longer as citizens, but as clients of state-funded services—or in some cases ignored.

This is an unproductive and disempowering (and expensive) way of dealing with people. It persists because it is in a sense easier than devising sustainable ways to integrate people with special needs into society and designing a system of supports that allows them to participate and that values their contribution. So long as Canada’s workforce was growing and its economy was secure, we could buy the convenience of not having to take seriously the challenge of doing away with poverty or ensuring immigrants could find jobs suitable to their professional backgrounds. They are supported, but in Amartya Sen’s phrase “not let into the game.”

Will this still be the case in the future? Or will governments decide that the cost is too high or other needs are more urgent and start cutting welfare programs, always an easy target? We may debate whether in a generation the financial cost of the benefits economy will still be accepted or affordable, but a more fundamental question is whether it is right to deny people the opportunity to participate fully as citizens, by contributing according to their abilities and interests to the wider society rather than being excluded by popular attitudes and bureaucratic procedures and disincentives that trap them in dependence. As leaders in the disability movement have pointed out, the greatest handicap people with a disability face is not their physical or intellectual challenges but the isolation imposed on them by the wider society.40 Preventing people from acquiring assets as a condition of eligibility for state support, to take an example, is one means of imposing dependence.

The Costs of Exclusion

Jean Vanier has taught by his example in l’Arche that it is through seeing others’ vulnerabilities that we become aware of and accept our own vulnerability, and thereby come to view exclusion and participation differently. Our present economic model places the greatest value on ‘efficiency’ and high performance, and consequently it resists making space for people who are perceived as less than fully “productive.” A resilient society, however, needs to focus less on narrowly-defined “efficiency” and more on the essential contribution diversity makes to social innovation.

An asset-based approach would facilitate everyone’s full participation in society according to their capacities. Education and training would be facilitated throughout a person’s lifetime, as in Scandinavia; addictions would be treated as far as possible as a medical rather than justice problem; incentives for employers to hire people with special needs would facilitate and share the cost of flexible work arrangements, etc. No one would be automatically excluded just because they are considered marginal or disadvantaged.

Much of the disruptive innovation that one observes now in the community sector is the result of organizations pushing beyond their traditional role of supporting and sustaining the “benefits economy.” Nick Saul at One Stop in Toronto wants to re-position food banks as community hubs in which supplementary food is merely one expression of community support for individuals; Michel Rivard of the Centre le Havre in Trois- Rivières and Jim Hughes, former executive director of Montreal’s Old Brewery Mission, refocused their shelters from warehousing the homeless to helping people get back on their feet as rapidly as possible. Many United Way/Centraides have similarly begun to shift from an essentially passive role of providing recurrent funding to social service agencies, to actively developing long-term strategies to reduce or eliminate poverty and exclusion. On a national level, initiatives like the Index of Well Being started by the Atkinson Foundation, and the Vital Signs report cards sponsored by community foundations in some fifteen cities across Canada, are beginning to give us a more complete picture of how we are doing than that provided by the one-dimensional indicator of GDP.

An action Agenda

The most innovative and politically transformative ideas—ideas in the defense of greater equity and justice—of the last 200 years have not only emerged in, but have been driven by civil society.

Dr James Orbinski, former president of Médecins Sans Frontières

If the creativity of Canada’s community sector is to be unleashed, everybody has a role to play.

First, the community sector needs a new self-image, not just as the caring sector but as the creative sector. As others have argued, it will not be taken seriously so long as it is identified by what it is not (non-governmental, not-for-profit), which conveys no sense of how it adds value to our lives, nor by the language of deprivation (helping people who are “vulnerable” or “under-privileged” or “falling through the cracks”). It does those things of course, and they are important. But they are rooted in a concept of charity and resignation that do not represent the dynamism of the community sector today, nor the hope and potential of what it can contribute tomorrow.

How those working in the sector conceive of its role, what it does and how it works, and articulate it to others actually goes a long way to determining what it can do.

Government must see the sector as an indispensable partner, not just tiresome “special interests,” or an optional instrument for delivering public services. We need an enabling infrastructure that levels the playing field between social enterprises and small and medium-sized businesses. This would include a high-level institutional link responsible for actively strengthening, not just narrowly regulating, the sector; a legal framework that encourages social enterprises, based on the uses to which all revenues are directed (i.e., for public benefit), not simply their source; and a range of policy measures that promotes the contribution by Canadians of time and money to the public good. As in Britain and the U.S., building the capacity of the sector should be viewed as an important means to strengthen citizen engagement and a democratic polity.

Business also has a role beyond just acknowledging the marketing value of the “triple bottom line.” Surveys demonstrate the value placed by employees on socially engaged employers who take seriously their responsibilities to all their stakeholders. Facilitating time off for staff to pursue projects in local neighbourhoods or overseas, encouraging and matching staff donations, collaborating actively in community building are becoming more common but are still far from the norm in the corporate world. The encouragement that the private sector routinely provides to business entrepreneurs should be extended as enthusiastically to social entrepreneurs.

Finally, donors have a role to play. Foundations in particular, with their combination of flexibility, long time horizons, and ability to shoulder risk, should be at the forefront of encouraging innovation. Establishment of a social finance market will be immensely helped by foundations’ growing interest in leveraging their assets at a time of reduced grant-making capacity by making program-related investments. Community Foundations of Canada and Philanthropic Foundations Canada, representing public and private philanthropy, are spearheading this effort.

Each time a person moves from isolation to connection our neighbourhoods become safer, our communities more vibrant and our society more cohesive. Given the enormity of the challenges we face in these infant years of the 21st century, building relationships, strengthening human bonds, expanding our capacity to care for one another are crucial acts. Our collective task is to end the poverty of loneliness. It is to learn to care for each other.

Vickie Cammack, at the Coady Institute’s From Clients to Citizens Conference, July 2009

Conclusion

Modernity was about expanding choices and opportunities, freeing the individual from involuntary ties and restrictive social norms. But it came with a price: a loss of social cohesion, weakened family ties, a heavy burden of personal responsibility, and a sense of isolation.

For most Canadians, individual well-being is defined in terms of material wealth, security, and fulfilling relationships. Business and government are expected to provide the first two; the third need is too often overlooked or treated as a purely private concern. Yet research findings tell us that relationships are key to maintaining physical and mental health, and to a sense of self-worth and satisfaction. Our status as customers or clients cannot substitute for belonging, and that is why the community sector matters. It is through participating and contributing that we belong and that we feel part of the broader society and that our lives have meaning. So long as the “voluntary sector” is treated just as a residual category of activities that meet needs not addressed by the market or the state, it will be left to struggle and improvise. The over-riding need for a society to succeed in a time of turbulent change is resilience, and our greatest need as humans is to be part of a network of supportive relationships.

The large-scale challenges facing Canada (and other countries) cannot be addressed adequately by partial measures and fragmented efforts. Indeed, it is too easy to confuse merely surviving the present crisis with adapting to a permanently changed or, more likely, constantly evolving landscape. Muddling through or trying to do more with less may be a formula for short-term survival but the long term demands resilience and adaptability. It is through community organizations of all kinds, voluntary associations of citizens banding together to pursue a cause, articulate a need, or help their fellow citizens, that society improves and the well-being of all is advanced. Hannah Arendt defines power as “the ability to act in common.” It is by giving form to that ability, and by unleashing imagination and commitment to innovate, collaborate and celebrate, that the community sector demonstrates its enduring value.

Notes

1 A word about terminology: in the U.K.; it is the Third Sector; in the U.S., it is the Independent Sector; in Canada, we refer to NGOs or the voluntary or not-for-profit sector. I will use the term “community sector.”

2 Many of the ideas in this article have been borrowed from others, but I would particularly like to thank Stephen Huddart, Judith Maxwell, Frances Westley,

and Tim Draimin for their suggestions.

3 By 2040, according to Statistics Canada, the ratio of people aged 15-64 to people aged 65+ will fall by half.

4 Globe and Mail, 17 July 2009.

5 Globe and Mail, 17 October 2009.

6 StatsCan projects that the only areas that will experience population growth are the Lower Mainland of B.C., the Calgary-Edmonton corridor, the Golden Horseshoe around Lake Ontario, and Montréal-Laval.

7 IBM, The Enterprise of the Future, Global CEO Study 2008.

8 Globe and Mail, December 3, 2009.

9 There are 83,000 registered charities in Canada (which has proportionately the second largest charitable sector in the world, after the Netherlands), and an equal number of incorporated not-for-profits. According to Imagine Canada, the core nonprofit sector (which excludes hospitals, universities, and colleges) accounts for 2.6%

of GDP or $29.1 billion; it has 1.5 million full-time equivalent (FTE) workers (paid and volunteers), which is 9.2% of the economically active population.

10 Statistics Canada, reported in the Globe and Mail, 16 November 2009.

11 Lynn Eakin, The Policy and Practice Gap: Federal Government Practice Regarding

Administrative Costs When Funding Voluntary Sector Organizations, 2005, and “The Invisible Public Benefit Economy: Implications for the Voluntary Sector,” in The Philanthropist, 2009.

12 Despite the name, voluntary organizations are not necessarily volunteer-staffed. It is the fact that support, whether of cash or of time, is voluntary that distinguishes voluntary organizations from government or business, where relationships are based on obligation or market transactions. In this sense, voluntarism is the life-blood of the sector; its capacity to attract and retain volunteers, whether as board members, service deliverers, or donors, provides the surest gauge of the community sector’s vitality.

13 HR Council for the Voluntary & Non-profit Sector, 2009.

14 See www.diversecitytoronto.ca .

15 http://courseresearch.timeraiser.ca/course.details .

16 See, for example, Nell Edgington at www.socialvelociy.net/2009/12/financing-not-fundraising .

17 Now hosted by Social Innovation Generation (SiG) at MaRS, Causeway also includes Al Etmanski of PLAN Institute, John Anderson of the Canadian Cooperative Association, Ted Jackson and Tessa Hebb of Carleton University, Community Foundations of Canada, The Wellesley Institute, Social Capital Partners, J.W. McConnell Family Foundation and others. More information can be found at http://socialfinance.ca .

18 Jim Collins, Good to Great and the Social Sectors: Why Business Thinking is Not the

Answer, 2005.

19 Michael Edwards, “Oil and Water or the Perfect Margarita?” Where is the ‘Social’

in the “Social Economy?” The Philanthropist, 22(2), 2009.

20 For information about SROI methodology. see www.redf.org .

21 See Jamie A.A. Gamble, A Developmental Evaluation Primer, The J.W. McConnell

Family Foundation, 2008.

22 For more on Santropol Roulant, see Warren Nilsson, The Art of Engagement at

Santropol Roulant, 2009.

23 For a list, see www.cicregulator.gov.uk .

24 See Richard Bridge and Stacey Corriveau, Legislative Innovations and Social Enterprise: Structural Lessons for Canada, B.C. Centre for Social Enterprise, February 2009.

25 B.C., a province at the forefront of new thinking concerning the community sector, is considering changes to corporate structures as a result of the Government

Non-Profit Initiative, and may also create a Blue Ribbon Panel on Social Finance.

26 Clay Shirkey, Here Comes Everybody, 2008, p.22.

27 The UK’s National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA),

for one, is offering a one-million-pound challenge prize, the Big Green Challenge, for community action on climate change. Ashoka has already run some 30 Changemakers competitions using a methodology that can be scaled at global, regional, or local levels.

28 Geoff Mulgan, Social Silicon Valleys: A Manifesto for Social Innovation, Young

Foundation, 2006.

29 www.sig.uwaterloo.ca .

30 Henry Mintzberg, Rebuilding Companies and Communities, Harvard Business

Review, July-August 2009.

31 For details of campus community-service learning (CSL) refer to www.communityservicelearning.ca

32 A recent paper by Adam Aptowitzer for the C.D. Howe Institute suggests creation of a Canadian Charities Council. See Bringing the Provinces Back In: Creating a Federated Canadian Charities Council.

33 For more information, go to www.sigeneration.ca .

34 The group included, among others, John Mighton (JUMP), Al Etmanski and Vickie Cammack (PLAN), Paul Born (Vibrant Communities), Leena Aguimeri (Child Development Institute), Mary Gordon (Roots of Empathy), Anil Patel (Framework), Jean Marie de Koninck (Nez Rouge), Dave Kranenburg (Meal Exchange),

Jane Rabinowicz (Santropol Roulant), and Nathan Ball (l’Arche).