Abstract: This article examines changes in Canada’s charity law between 2001 and 2009, the dates of two conferences on Commonwealth charity law held by the Australian Centre for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies in Brisbane, Australia. It suggests that attempts to change charity law in Canada have constituted tinkering, rather than involve any substantive change. It hypothesizes that one of the reasons for the lack of progress has been the failure of the voluntary sector to attract public attention and, therefore, public support for legislative change.

Résumé: Cet article examine les changements dans la loi canadienne sur les œuvres de charité entre 2001 et 2009, les années de deux conférences sur les lois caritatives organisées par l’Australian Centre for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies à Brisbane, Australie. Il suggère que les tentatives de modifier la loi caritative au Canada ont été faibles, n’entraînant aucun changement de substance. Il propose l’hypothèse qu’une des raisons pour le manque de progrès a été l’échec du secteur bénévole dans sa tentative d’attirer l’attention du public et, ainsi, son appui pour des changements législatifs.

Introduction

No one can suggest that Canada has experienced a revolution in the development of charity law since the last Brisbane conference in 2001; indeed, one would be hard-pressed to suggest even much of an evolution in that period. Despite the high (some would argue unrealistic) expectations of some for fundamental changes in how charities are defined and regulated, one must conclude that the last years have seen, at best, tinkering at the edges.

This article will put forward the argument that the lack of development of charity law is, at once, complex and entirely simple. The complexity comes from a regulatory environment developed to fit a dysfunctional constitutional and legal arrangement for the supervision and regulation of charities; the simplicity from the lack of drive by charities to overcome the inertia of the status quo preferred by those who could change the situation.

The failure of Canada’s voluntary sector to achieve a meaningful level of public awareness of its scope and contributions is, at least in part, the causal factor for a lack of attention at the legislative level: the lack of public awareness translates into a lack of public support for the sector qua sector which, in turn, translates into a lack of incentive for regulators or legislators to act. Moreover, this lack of lack of awareness and support renders the sector (qua sector) impotent to have significant impact on public policy. This was most recently evidenced by its failure to achieve any significant government response to requests for inclusion in stimulus projects proposed in response to the global financial crisis.

After reviewing the current situation involving charities in Canada, discussing significant developments since 2001, and offering hypotheses for lack of progress in the field of charity law, this article will conclude with a description of issues likely to be at the forefront of demands for law reform in the next several years.

Context

Size and distribution

Canada has an estimated 161,000 voluntary-sector organizations,2 almost equally divided between registered charities and nonprofit organizations.

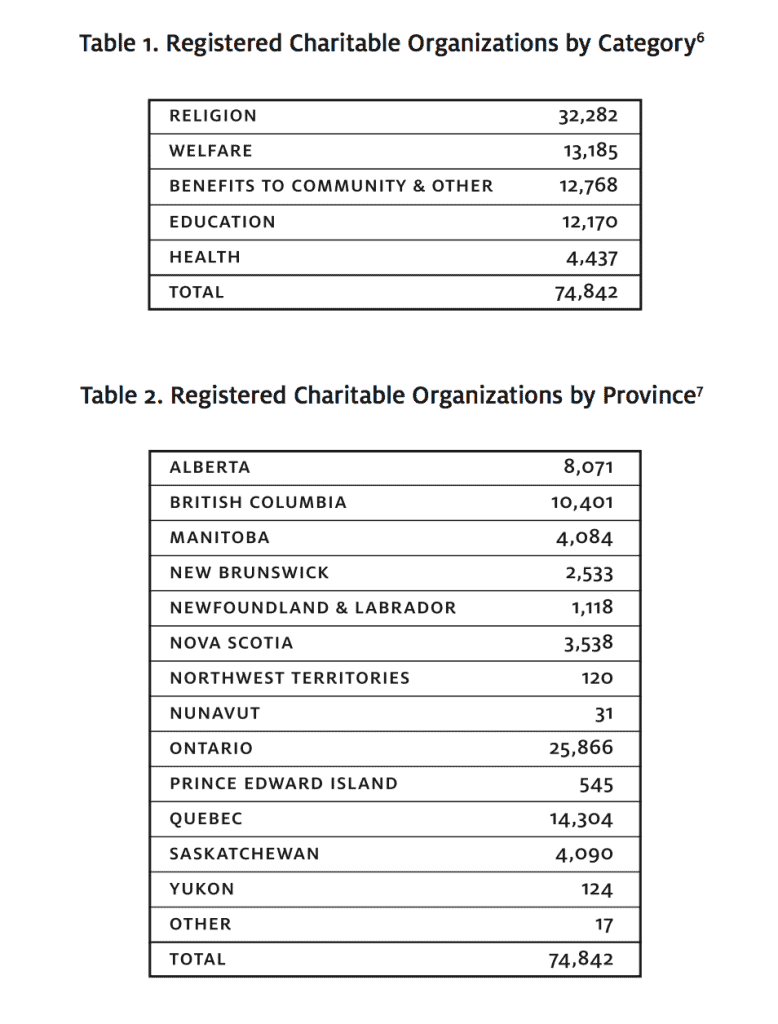

There are currently slightly fewer than 84,600 registered charities in Canada.3 Of these, about 75,000 are charitable organizations, almost 5,000 are public foundations, and 4,780 are private foundations.4 Under Canadian law, charitable organizations are generally those that deliver direct service. Public and private foundations are generally those that support charitable organizations.

Table 1 shows the breakdown of the types of registered charitable organizations,5 while Table 2 shows the geographic location of the head offices of these organizations.

In common with other jurisdictions, the number of small charities greatly exceeds the number of large charities. Based on data reported on annual returns filed by charities for fiscal years ending in 2004:

Privileges

All nonprofit organizations in Canada are exempt from the payment of taxes on income.

Donors to registered charities are able to claim a tax credit that reduces taxes payable to federal and provincial governments.8 The total value of the tax credit depends on the donor’s province of residence.

For federal tax purposes, the credit is 15% on the first $200 donated and 29% on all amounts above $200. Each province establishes the value of the tax credit for donor-taxpayers. The combined tax credit is as high as 50% in Alberta and 53% in Quebec.

Donors may claim a credit for donations of up to 75% of their net income and 100% of net income in the year of death. Amounts in excess of the maximum may be carried forward for up to five years.

In 2006, the Canadian government eliminated capital gains tax that would otherwise be payable when publicly traded securities are donated to a registered charity other than a private foundation. The following year, the government extended that exemption to do- nations of publicly traded securities made to a private foundation, but subject to certain issued by a company.

Regulatory environment

Under the Canadian constitution, supervision of charities is within the jurisdiction of the provinces. In practice, however, it is the federal taxing authority – the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) – which is seen as the primary regulator of charities.

This situation has arisen because the major benefits available to charities – the exemption from the payment of tax on income and the ability to offer tax credits to donors – are provisions contained in the federal Income Tax Act. Organizations apply to CRA for registration as charities and, if approved, are then subject to audit and enforcement activity by CRA’s Charities Directorate.

Only one province, Ontario, has a formal mechanism for supervision of charities. Through the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee, the Ontario government exercises some supervisory authority over charities, primarily in issues related to fiduciary responsibilities of trustees. Several other provinces have passed legislation related to fundraising and exercise some control over the fundraising activities of nonprofit organizations, but rarely become involved beyond that.

There is more interface, however, when provinces start regulating gambling activities. Under federal legislation, the provinces can issue licences to organizations undertaking charitable activities allowing them to use lotteries or participate in casinos to raise funds. In establishing the regimes for such licensing, provinces have established different eligibility rules, creating different rules as to what is charitable in each province. While, for the most part, these definitions accord with what CRA regards as charitable, this is not always the case.

The Income Tax Act contains no definition of “charity.” The courts apply the Pemsel categorizations in determining whether an organization is charitable.

For all practical purposes, there is no regulation of nonprofit organizations that are not charities.

Judicial oversight

There continues to be a paucity of court cases establishing what is charitable in 21st-Century Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada has heard only three charity-law cases in the last 50 years.9

Unlike most other common-law countries, Canada has erected significant barriers to developing charity law through the courts. Appeals from the regulator’s decisions to deny charitable registration or to remove registration do not proceed to a trial court for hearings, but rather are conducted, based on the record, by the Federal Court of Appeal. Whereas taxpayers may proceed through informal internal appeal mechanisms within CRA and then go to the Tax Court of Canada, the same does not hold true for organizations that are denied charitable registration or wish to protest the revocation of their charitable status.10 The cost and formality of a hearing before Canada’s second-highest federal court is a prohibitive exercise for all but the most wealthy.

Other decisions made by the regulator are, in most cases, subject to judicial review by the Federal Court Trial Division. No such cases have been brought, largely because those other types of decisions are of little consequence to most charities.

Developments in charity law, 2001–2009

Voluntary Sector Initiative

The Voluntary Sector Initiative (VSI) was, arguably, the most innovative, successful, and misunderstood vehicle ever devised to address issues related to Canada’s voluntary sector.

As a result of work undertaken by the voluntary sector to identify issues, and the inclusion in the governing party’s election policy of a commitment to re-examine its relationship with the sector, the prime minister of the day announced the creation of a program unlike any previously used in Canada to develop public policy.

The government and sector established seven joint tables, composed of equal numbers of senior government officials and senior people from the voluntary sector, and each charged with examining an aspect of the relationship between government and the sector. For the purposes of this article, the most relevant table was the Joint Regulatory Table (JRT).11

The JRT had a six-fold mandate:

For some, the JRT was a major disappointment, but some of that disappointment seems to be based on a lack of understanding of the Table’s mandate. For example, some were distressed that the JRT did not develop recommendations for a definition of charity. Others were unhappy because the Table did not make advocacy the focus of its attention.12 These commentators and detractors failed to accept that the Table was bound by its mandate as established by the federal Cabinet in consultation with a group of leaders of national voluntary sector organizations.

Notwithstanding the criticism, the Table delivered, in March 2003, a report with 75 recommendations for changes. Slightly less than a year later, the Canadian government adopted 69 of the recommendations, representing the most significant change in charity law in more than 40 years.

What follows next is a brief examination of the JRT’s recommendations and the government’s response.

Transparency and accountability

The JRT made a series of recommendations of characteristics or traits that should govern a charities regulator, whatever model of regulation was chosen. These recommendations included provisions for the publication of virtually all policy statements used by the regulator,13 the development of educational programming about charities’ obligations under the Income Tax Act, and the development of on-going mechanisms for dialogue including the establishment of a continuing committee to advise the Minister of National Revenue on matters related to charities.

All of these recommendations were adopted by government. Even during the life of the JRT, the Charities Directorate was making more information about its policies and operations available on its website. A granting program was established whereby the Charities Directorate contracts with voluntary-sector organizations to educate charities about various obligations they have under the Income Tax Act. The Directorate began a formal process of widespread consultations on the development of new or amended policies, providing full opportunity for charities and others to comment before the policy was put in place. An advisory committee was appointed by the Minister of National Revenue and functioned effectively for almost 18 months until it was abolished by a newly elected government of a different political stripe.

Certain other recommendations, including publication of reasons for Directorate decisions on registration cases, were adopted by the government but have not yet been implemented. However, as a result of Table recommendations, the amount of information publicly available about Directorate decisions has increased significantly. The government did not, however, accept the Table’s recommendation that the same amount of information should be available about organizations that had been refused charitable status. This was seen by the Table as an effective mechanism to examine the on-going evolution of charity law and as a way of identifying any possible systemic bias in the application-examination system. It was seen by government as overly intrusive in the affairs of an organization that was not going to receive any public benefit through charitable registration.

The Table’s review also underlined the importance of the role of charity examiners in an area where they must not only administer a law but also help develop it through the type of analogies called for in the common law. It called for additional professional development and reclassification so that examiners could make a career of working in the field, thus avoiding the ongoing change of staff. While government accepted this recommendation in principle, the problem has not been addressed and the turnover of staff continues to be a problem for the Directorate and those who deal with it.

Appeal system

The JRT reinforced the concerns raised about the appeal mechanism. It observed that charity law could not develop without a robust set of court decisions that reflected the type of evolution identified by many common-law courts, including the Supreme Court of Canada in the Vancouver Society case.

The Table recommended that decisions of the regulator be subject to internal reconsideration by a unit outside of the Charities Directorate, but staffed by people with experience in charity law. Should that reconsideration leave the matter still in contention, an appeal would lie to the Tax Court of Canada, where a hearing de novo would take place. Both the organization and the Directorate would be allowed to call witnesses and to cross-examine. An appeal from the Tax Court of Canada would lie to the Federal Court of Appeal, where the appeal would be heard on the basis of the record developed in the Tax Court. Thereafter, with leave, an appeal could be taken to the Supreme Court of Canada.

In an attempt to encourage the development and litigation of cases that were likely to further charity law in Canada, the JRT also called for the establishment of an appeal fund similar to the Court Challenges Program, which provided funding to individuals bringing court actions that engaged Canada’s constitution.14

The federal government accepted the recommendation for an internal reconsideration process, but did not accept the remainder of the Table’s proposals.

Intermediate sanctions

Prior to the Table’s report, the only enforcement mechanism available to the Charities Directorate was revocation of charitable status.15 This was seen by the JRT as too blunt an instrument to have as the sole vehicle for dealing with non-compliant charities. Moreover, it seemed to prevent action against certain types of charities, including universities and churches, where no Minister would ever agree to elimination of the organization’s charitable status.

The Table therefore recommended the introduction of a system of intermediate sanctions that are significantly less complicated than those used in the United States. In adopting the recommendations, the government established a set of “offences,” such as improper issuance of donation receipts or the carrying out of improper business activities, or the provision of an undue benefit to any person. Penalties are attached to each type of offence. The Directorate also has the option of suspending a charity’s status as a qualified donee for up to one year. While allowing the charity to continue its operations, suspension prohibits it from issuing receipts to its donors, thus eliminating the tax credit to the donor.

The use of sanctions, thus far, has been minimal. This is possibly due to the Directorate’s enforcement actions of late being focused on the improper use of tax shelters involving charities.

Regulatory models

In the period leading up to the JRT, and during its life, some people called for the establishment of a new type of regulatory regime, similar in nature and design to the Charity Commission of England and Wales. They believed that this was a model that would encourage development of charity law in a way that was appropriate for Canada in the 21st Century. Moreover, they said that the establishment of a separate commission would remove the perceived bias in having a tax-collection authority responsible for deciding whether an organization would be exempted from the payment of income tax.

A model similar to the Charity Commission was examined by the JRT and described in its report. The fundamental problem, according to the Table, was that such a model could not easily exist within Canada’s constitutional structure.

As noted earlier, the primary responsibility for the supervision of charities constitutionally belongs to the provinces. The federal government’s authority over charities comes only from the fact that there are benefits given to charities under the Income Tax Act, a federal statute. In essence, therefore, the Charities Directorate’s role is limited to ensuring that an organization qualifies (and maintains qualification for) those benefits. However, given that those benefits are the sole reason most organizations seek charitable status, the federal role becomes paramount in fact, if not in law.

By contrast, a significant role of the Charity Commission of England and Wales is to ensure that trustees of charities exercise their fiduciary responsibility over that property, which is impressed with a charitable trust. This is a role that, under Canada’s constitution, would be within the exclusive jurisdiction of the provinces.

The JRT obtained legal opinions from lawyers within and outside government and concluded that it could see no way that a regulatory body similar to the Charity Commission could be established in Canada without constitutional challenge. The only exception would be if the federal and provincial governments entered into contractual arrangements in which the federal government, through the Charity Commission, would exercise the provincial authority on behalf of the province. Given Canada’s political makeup, such a model is unlikely.16

The Table examined and commented upon four regulatory models in its report. Government has taken no steps to change the regulatory regime, and the Canada Revenue Agency remains (and is likely to remain) the primary federal regulator.

Administrative policy decisions

CRA, like most regulators, develops and adapts its policies over time. In some cases, these changes can signal an expansion of thinking of what is charitable while, in other cases, the policy changes out a new area of concern.

One of the most significantly commented upon changes related to advocacy.

The Income Tax Act provides a 10% safe-harbour provision for charities to undertake advocacy. That is, a charity may expend up to 10% of its assets on advocacy activities without being accused of failing to use all of its resources for charitable activities. Some saw that limit as an inappropriate vehicle used to silence the voice of charities. They argued that a charity should be allowed to undertake any amount of advocacy activity so long as the advocacy did not become a collateral purpose.

While the JRT was not mandated to deal with the issue of advocacy (most often in Canadian law called “political activities”), it was instrumental in an updating of policy that clarified existing policy and allowed some greater scope for charities to undertake advocacy activities.

As a result of on-going discussions at the Table, a group began work on the topic through what was called the “alternative mechanism.” Several of the Table members from government and the sector met outside of Table meetings to advise, unofficially, CRA on its advocacy policy. The resulting policy made few fundamental changes, but clarified the policy, allowing charities to realize that CRA regarded much of what had been called advocacy as, in fact, charitable activities designed to further the organization’s charitable purposes. The issue has attracted little attention or comment in recent years.

CRA has introduced or amended a number of other policies in recent years that seek to bring charity law somewhat closer to the 21st Century. These include policies providing for the registration of organizations assisting ethnocultural communities and clarifying the policy on the eligibility of umbrella or peak organizations for charitable status.

One of the more contentious policy issues relates to fundraising. The Charities Directorate issued a draft policy setting out its views on acceptable fundraising activity and reporting, including a graph indicating what percentages of expenditures on fundraising activities might be acceptable. The sector responded negatively to the draft policy, questioning the restrictions CRA sought to support. The policy also raises constitutional questions, since the regulation of fundraising would fall into the provinces’ supervisory authority, a criticism CRA answered by saying that the question of expenditures relates to a determination of whether a charity is using all of its resources for charitable purposes.17 The final policy is expected to be released in the second quarter of 2009.

Far less contentious and welcomed by many is a draft policy on the potential of some sports activities to be registered as charitable. Although arguably not establishing anything new to charity law, the proposed policy explains in greater detail how an organization might qualify for charitable registration if it positions itself so that the sports activity is ancillary and incidental to another charitable purpose, such as the promotion of health.

Judicial decisions

In the last eight years, the Supreme Court of Canada has considered only one case dealing with the question of what is charitable at law. The Federal Court of Appeal considered nine cases dealing with the same question. It is fair to say that none of these 10 decisions has changed the law of charity in Canada.18

The Supreme Court of Canada case, A.Y.S.A. Amateur Youth Soccer Association v. Canada (Revenue Agency,)19 reiterated that an organization formed for the promotion of sport was not charitable. Some commentators have suggested that the Court’s decision in that case limited the scope for expansion of the common-law definition of charity, but a reading makes clear that the Court was addressing the issue of whether holding a sports organization to be charitable represented an incremental or wholesale expansion of the common-law definition. Given that the evidence before the Court was that 21 per cent of all Canadian nonprofit organizations are sports and recreation organizations, it would have been difficult for the Court to conclude that this was an incremental change. Throughout the rest of the decision, the Court acknowledges the long line of cases holding that the definition of charity must evolve with society.

The Federal Court of Appeal cases upheld a line of cases dealing with foreign activities, business activities, political activities, and use of charitable resources. No new ground was broken.

Over the course of the last year, the majority of court cases involving charities have been procedural matters, primarily around attempts to seek to delay the regulator’s actions to revoke the registration of a charity. These cases have arisen in the context of CRA taking an aggressive stance against those charities which it considers to be improper tax shelters.

In short, the fears raised by the JRT about the lack of evolution in our understanding of charity law have been proven by the subsequent events.

Drivers and barriers for reform

Drivers

With one exception, one is hard-pressed to find a major demand for change or modernization of charity law in Canada.

Some members of the charity bar look with envy at the United Kingdom and wish “we could be more like them.” The expansion in the Charities Act 2006 of the types of organizations with charitable status along with the forward-looking approaches of the Charity Commission of England and Wales seem a sort of nirvana to those who practise in the field of charity law.

There is no corresponding demand to be seen among most of those who work within charities. Their concerns are far less prosaic. Their requests to government focus not on improving the law of charity, but rather on improving the tax treatment of donations, in the hope they can attract more and larger donors. These calls are traditionally answered by government’s assertion that Canada’s tax treatment of donations is the most generous of the G-8 countries.

The one exception is in the field of the social economy or social enterprise. A small, but increasing, number of people in the field are pushing government to make legislative changes that will allow the expansion of social-enterprise activities. The movement has not yet reached a critical mass, in part perhaps because there are significantly different understandings of what is meant by “social enterprise.” To some, it is a mechanism by which charities can seek to raise funds through businesslike activities, some of which are already permitted under Canadian law. To others, it is a much broader concept that includes the potential for charitable dollars to be used to support organizations that have a social mission, whether or not they have such usual attributes as a nondistribution clause.

The arguments in favour of expanding the possibility of preferential tax treatment to investors in social enterprise focus around it being an alternative to government having to pay to deal with social issues. If organizations are able to entice donors with the potential of tax credits, the argument goes, they will be able to reduce their demand for government funding. The contrary view is that government should not be excused from paying to deal with social issues and that the addition of more organizations able to award tax credits to donors or investors will result in a finite number of dollars intended to support the public good being distributed more diffusely, resulting in a reduction of service.

Barriers

While the number of drivers for reform are minimal, the barriers to modernizing charity law in Canada are numerous. Moreover, they tend to be institutional or systemic in nature, making changing them a formidable task.

The most systemic of these barriers is Canada’s constitutional division of powers. While the federal government, through CRA, is seen by most charities as their sole regulator, this is not the case. But the split jurisdiction means that there are, effectively, at least 14 definitions of charity in Canada – that of the federal government (which most closely resembles the definition in other common-law countries) and those of the 10 provinces and three territories (which tend to deal with political or social demands rather than any common law).

In response to recommendations from the JRT, CRA’s Charities Directorate has sought to establish closer working relationships with those provincial and territorial departments that deal most often with the regulation of charities. While there is evidence of some willingness to co-operate, the idea of any co-ordination of charity regulation is likely a non-starter. Because of this, the idea of a charity commission similar to that in other countries is an appealing topic for discussion, but unlikely ever to emerge.

An offshoot of this constitutional divide is an inability to raise the issue of charity regulation to a political level. In Canada, there are annual meetings of federal and provincial ministers in particular areas of responsibility. For example, the federal and provincial attorneys-general meet to discuss issues related to criminal law or model laws in the civil field.20 Ministers of finance hold similar meetings, as do the ministers responsible for consumer protection. But the opportunity for joint meetings of ministers responsible for charity regulation never arises, because each province has given that responsibility to a different ministry. In some provinces, for example, the attorney general has responsibility for charities, while in others, the responsibility may belong to a department of consumer affairs, the finance department, or a ministry such as Alberta’s department of culture and community spirit. Thus, there is no opportunity for these ministers to meet as peers and discuss pan-Canadian issues related to charities.

While the constitution is a significant problem, the most relevant barrier to modernizing charity law is the lack of a court system that would allow for a greater number of cases to be decided.

As noted above, the Federal Court of Appeal is the first level of judicial appeal from any decision to deny an organization charitable registration or to remove that status from an organization – the very types of cases which are most likely to lead to the incremental evolution of charity law. Mounting an appeal to that court is an expensive proposition, charity but has been denied registration is unlikely to have that sort of money available. Moreover, an appeal is based solely on documentary evidence; the court has no evidence of current community needs or standards or testimony that is subject to cross-examination to determine institutional biases.

Because there are so few cases taken to the Federal Court of Appeal, there is a similar dearth of decisions on charity law from the Supreme Court of Canada. That court has heard more admiralty cases than charity law cases!

There is no justifiable reason for the current appeal structure. For years, there have been calls to change it to mirror the appeal system used for any other taxation matter: an internal review by CRA followed by a hearing de novo in the Tax Court followed by an appeal on the record to the Federal Court of Appeal and, if leave is granted, to the Supreme Court of Canada. Yet calls for reform have consistently fallen on deaf ears.

The federal legislation dealing with charities is also a barrier to modernization of charity law. While CRA administers the provisions of the Income Tax Act, it is not responsible for the development of the legislation. That role is jealously guarded by the Department of Finance. Like most taxing statutes, the Act is incomprehensible and its ability to deal with issues specific to non-tax-paying entities such as charities is limited, because language used in one section can affect legislation dealing with entirely different matters. But, I submit, the biggest barrier to the modernization of charity law is the very group of organizations affected by that law – Canada’s charities.

There is an almost total lack of understanding of, or concern about, the development of charity law amongst most but the largest charities in the country. While their requests for changes in tax treatment or support for social enterprise may invoke the law of charity, they are not seen in that vein, but rather as ways to increase fundraising mechanisms to support their work. While not inherently wrong, such an approach fails to examine the systemic barriers and potential system aids that could come from modernizing charity law. One-off decisions, whether by the regulator or legislator, do not have the systemic impact required to bring Canadian charity law into line with other developments in the 21st Century.

The voluntary sector in Canada has not banded together to determine what it wants or how it should go about getting it. It has been singularly unsuccessful in creating an awareness within government or the general public of its size and its reach. As a result, it has been unable to build the level of public support that would force legislators and regulators to pay attention to its opinions. This is not to say that the sector lacks public support; indeed, studies consistently show that the voluntary sector enjoys the trust of the vast majority of Canadians, who also see charities as being better than government at understanding and meeting the needs of Canadians.21 Yet the sector has not been able to translate that trust into support for legislative or regulatory changes.

The most recent example of this has been the inability of the voluntary sector to move government to include the sector in any sort of stimulus package being developed to address the current global recession. Notwithstanding arguments that during a recession the only increase in demand is for services offered by the voluntary sector or that money invested in charities remains in the community rather than travelling outside the country to pay for equipment used in infrastructure projects, the sector has not been able to persuade the federal or provincial governments to pay special attention to it. Indeed, just the reverse is occurring, with provincial governments cutting money available to charities and other nonprofits in an attempt to limit budget deficits.

One can make an argument that there is no such thing as the voluntary sector – that it is the product of economists and academics who had no other category that seemed appropriate to house certain aspects of consumer spending. Yet, by whatever name it is known, that group of organizations – some 85,000 charities in Canada – are all bound by the same charity law and should have far more concern about its development or, more appropriately, its lack of development.

The future challenges

One must proceed cautiously when entering the nebulous discussion about what others may do. That is especially true if those “others” are legislators and regulators.

Canada’s attempts at modernizing the law of charities have constituted little more than tinkering at the edges. While substantive changes resulted from the report of the Joint Regulatory Table, those changes were limited by the scope of the Table’s mandate. More important, those revisions were the first substantive changes in more than three decades. Revisions to policies by CRA have, for the most part, been helpful and expanded slightly the scope for charitable activity in the country.

Modernizing the law of charities in Canada will require much more fundamental examination than that. It would require, first, a decision as to whether the law of charities was meant to be a social policy with fiscal implications or a fiscal policy alone. Government treatment of charitable donations.22 Leaders of the voluntary sector respond by saying that figure needs to be offset by the (indeterminable) amount of money that government would have to spend in the absence of charities. These points and counterpoints hide the argument about whether charity law is intended, first and foremost, to address social issues or fiscal issues. It also raises questions about whether some of the barriers holding back the development of charity law are, in fact, deliberate decisions to prevent that evolution.

Whatever the result of that decision, it is clear that the current legislative provisions, including (or perhaps particularly) the judicial oversight process, do not work. While legislation such as the Bank Act is automatically reviewed every 10 years, the charity provisions of the Income Tax Act have never gone under the microscope as a package. As with other developments, there has been tinkering here and there, but no one has stood back and asked whether, in toto, those provisions make sense in the 21st Century. One would be hard-pressed to conclude that they do.

It is likely that government will have to address the issue of social enterprise at some point in the next several years. In light of some of the people promoting the concept and of developments in other countries, government will have to decide whether to treat these organizations as charities, like charities, or through some other mechanism. The decision may open the door to consideration of a statutory definition of charity or the “charity plus” model advocated by Arthur Drache and modelled in the Charities Act 2006 in England.

Such an examination could (and should) precipitate a review of all of the charity-law provisions in the Income Tax Act. It could do much to address concerns that have been raised by charities and their advisors over the years. It is highly unlikely, verging on the unimaginable, to believe that the federal government would give up direct regulation of charities in favour of a charity commission or other arm’s-length body. So long as the government maintains a generous tax regime available for donors to charities, it will wish to have the direct contact with the regulation of those charities. But issues related to business activity, advocacy, and the complex disbursement-quota rules could be examined as a package and amended so as to make sense for charities and for Canadians.

If government were to become serious about encouraging the evolution of charity law (a premise not yet proven by any action of the federal government, whatever its political stripe), then it would immediately move to allow more cases to come before the courts through a change in the appeal process. It would recognize that it is difficult for a regulator to follow Pemsel’s provisions for analogies to be drawn if there are no court decisions to which analogies might be drawn.

All of this presupposes that government pays any attention to the advocates, another premise that might fail in analysis. It is equally possible that nothing will change and that the future of Canada’s charity law will evolve not through incremental change but rather through endless tinkering.

Notes

This article was originally presented as a paper accompanying a speech delivered at

in Brisbane, Australia, April 16, 2009.

1 Statistics Canada, Highlights of the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary

2 Organizations, rev 2005. Canada Revenue Agency, Charities Directorate website: http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/

3 ebci/haip/srch/sec/SrchInput01Validate-e [April 10, 2009]. Ibid.

While Canada, in common with other common-law countries, uses the Pemsel categorization for registration purposes, statistics available from the Canada Revenue Agency Charities Directorate use different category descriptors.

4 +++++++++++++++5

Data obtained from Canada Revenue Agency Charities Directorate website, op cit,

6 retrieved April 10, 2009. Ibid.

Similar tax-credit privileges are available to certain other types of organizations which, while not registered charities, are “qualified donees” within the meaning of the Income Tax Act. These include the Crown in right of Canada or a province, a municipality, a registered Canadian amateur athletic association; a housing corporation resident in Canada constituted exclusively to provide low-cost housing for the aged; the United Nations and its agencies; a university that is outside Canada that is prescribed to be a university the student body of which ordinarily includes students from Canada; a charitable organization outside Canada to which Her Majesty in right of Canada has made a gift during the fiscal period or in the 12 months immediately preceding the period and Her Majesty in right of Canada or a province.

Guaranty Trust Company of Canada v. Minister of National Revenue, [1967] S.C.R. 133; Vancouver Society of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women v. M.N.R.[1999] (1999), 59 C.R.R. (2d) 1; A.Y.S.A. Amateur Youth Soccer Association v. Canada (Revenue

10 As discussed, charitable organizations that are the subject of intermediate sanctions may use the same process as other taxpayers, but not for decisions that relate to registration or revocation.

11 In the interest of full disclosure, the author was the co-chair of the Joint Regulatory Table.

12 As identified below, members of the Joint Regulatory Table did make advocacy an issue and while not discussed in the JRT’s final report, significant improvements were made to the advocacy (political activities) policy of CRA.13 Policies related to enforcement were excluded.

14 The Court Challenges Program was eliminated in 2006.

15 The Charities Directorate could (and still does) use undertakings or compliance agreements voluntarily entered into by a charity, but could not unilaterally take such steps. This was not usually a problem, given that the alternative was the threat of loss of charitable status.

16 An analogous situation exists within the field of regulators of the stock markets. Successive federal governments have called for a single national regulator, a call that is just as routinely rebuffed by the provinces.

17 The Income Tax Actitable purposes, including administration and fundraising. There is no recent data to indicate whether those figures remain realistic some 20 years after they were introduced. There is also some argument that the Vancouver Society case stands for the proposition that fundraising for a charitable purpose is, in itself, a charitable activity. 18 One could argue that one case changed the law. Earth Fund v. Canada (Minister of National Revenue), 2002 FCA 498 clarified that the “destination-of-funds” test was not a part of Canadian law. Some members of the charity bar had long held that Alberta Institute on Mental Retardation v. Canada, [1987] 3 F.C. 286, (1987) 76 N.R. 366, [1987] 2 C.T.C. 70, (1987) 87 D.T.C. 5306 (F.C.A.), leave to appeal dismissed, [1988] S.C.C.A. No. 32 stood for the proposition that any business activity by a charity was acceptable so long as the proceeds of that business activity were used by the charity for charitable purposes. CRA had never accepted that proposition. The Earth Fund case resolved the question.

19 2007 SCC 42.

20 In Canada, criminal law is within the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government, while matters related to property and civil rights are within the exclusive jurisdiction of the provincial and territorial governments.

21 Muttart Foundation, Talking About Charities 2008, available at www.muttart.org. This was the fourth of a series of public opinion polls assessing attitudes toward charities and issues impacting charities. Public trust in charities has consistently exceeded

22 Canada, Tax Expenditures and Evaluations 2008.