This article is based on a presentation by the author to the Third National Forum for the Public Policy and Third Sector Initiative, Advocacy, Engagement and Consultations: The Voluntary and Government Sectors, School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, October 25–28, 2002.

Introduction

Any attempt to compare political or social systems in Canada and the United Kingdom must acknowledge that it is a very complex undertaking and that the motivations for such a comparison, e.g., ammunition for policy debates, system generalizations, performance measures, and knowledge transfer, can easily influence both the methodology and outcome of comparative studies (Klein, 1991).

Three Stream Model of Policy Development

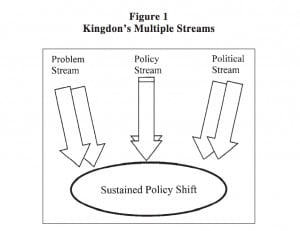

John Kingdon’s “multiple streams” approach to framing policy development provides a means to explore the interrelationship of three “largely independent streams”: problems, policies and politics (see Figure 1). The dynamic associated with these three streams and the extent to which they are synergistically linked at a point when a policy window opens determine whether advocates or policy entrepreneurs are in a position to press their positions and to succeed in effecting change (Kingdon, 1995).

The Problem Stream

The problem stream addresses the issue of why and how particular problems come to occupy the policy agenda. Included here are focusing events such as crises and disasters, feedback from current program operations, and availability of indicator data. For example, while the actions of some voluntary organizations are periodically brought into question by the media or are found to be corrupt, the lack of any widespread evidence of systemic mismanagement in either Canada or the United Kingdom gives this issue a relatively low profile and relegates it to existing regulatory mechanisms exercised by the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (CCRA) and the Charity Commission for

Figure 1 Kingdon’s Multiple Streams

England and Wales (CCEW), respectively. In the United Kingdom, indicator data, which have been accumulating since the mid-1990s, have created a critical mass of information on the financial size and employment contributions of the sector and of time trends data on volunteering and charitable giving (Kendall, 2000).

These same data, while available, are not as mature in Canada, but the cumulative policy impact of the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations undertaken by the Canadian Centre for Philanthropy, together with the inclusion of the voluntary sector in the system of Satellite Accounts by Statistics Canada, are important developments (VSI, 2002a; VSI, 2002b). This information and analysis is designed to create a clearer and more dynamic sectoral profile, which will be of use to many. However, it is the interpretation of these data, not the statistics themselves (Kendall, 2000), and their relationship to existing or pending policy and political developments, which will ultimately determine their impact (Kingdon, 1995). If, for example, results from the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations are found to coincide or become affiliated with a major social policy debate or political ideology, the Survey could take on a significant role, increasing the political status, profile, contribution, and public expectations of voluntary organizations and the sector-at-large.

The Policy Stream

The policy stream, in which policy alternatives are generated and championed by advocates, has been likened by Kingdon to a policy primordial soup in which a variety of combinations and permutations of ideas float around until the right combination of (1) technical feasibility, (2) congruence with community values, and (3) anticipation of future constraints, is reached (Kingdon, 1995).

In the United Kingdom during the 1990s, the CENTRIS report, Demos report, and the report of the National Council of Voluntary Organizations (NCVO) Commission on the Future of the Voluntary Sector all reflected variations on the theme of a potential role and future for the voluntary sector in the United Kingdom. Of these three, the NCVO report entitled Meeting the Challenge of Change: Voluntary Action into the 21st Century, commonly called the Deakin Report (NCVO, 1996) was, like that of the Voluntary Sector Roundtable (VSR) report of the Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector in Canada (Broadbent, 1999), also known as the Broadbent Report, perceived as a “consensus” document and a reflection of voluntary sector issues and concerns (Kendall, 2000). Viewed against Kingdon’s criteria, the 1996 Deakin Report was seen by the governing Conservatives as lacking value, acceptability, and technical feasibility, which was not a surprise, but struck a chord with the opposition “New Labour” Party. In the context of the pending national election, the Deakin Report succeeded by all three criteria, thus creating a viable and timely opportunity for New Labour to stake out its own distinct policy position in relation to the voluntary sector (Deakin, 2002a). No such political liaison has occurred in Canada for a number of reasons.

Opposition parties in Canada are currently weak and reflect distinct regional or ideological interests, thus limiting the available venues for exercising the policy interests of the voluntary sector, even though the number of Canadians associated with NGOs now exceeds those affiliated with political parties (Bennett, 2002). Combined with the 10 per-cent rule, inherent CCRA bureaucratic secrecy, and the discretion afforded organizations that advocate on behalf of issues favourable to government policy, it’s of little surprise that the current situation has been described as a de facto muzzle on legal dissent and social justice issues (Harvey, 2002).

The United Kingdom, like Canada, prohibits charities from being formed solely for political purposes, but the U.K.’s Voluntary Sector Compacts and the independent Charity Commission not only recognize charities’ historical contribution to social reform, but view credible and legitimate advocacy as an entitlement and as ancillary to furthering the “public benefit” aims of charity (CCEW, 1997; McIntosh & Dewar, 1998; Straw & Stowe, 1998). The Scottish Compact goes as far as to “recognise and support the sector’s independence, including its right to comment on and challenge government policy” (McIntosh & Dewar, 1998).

Carolyn Tuohy, who has written extensively on the dynamics of health policy, has analyzed the respective policy changes in health systems in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom using Kingdon’s paradigm. Her analysis is instructive for the current discussions concerning advocacy, engagement, and consultations.

First, major policy changes, such as advocacy rights in Canada or the most recent proposed charity reforms in the United Kingdom, occur only when two circumstances converge. The first circumstance is when the political system provides a consolidated base of authority for policy action (Tuohy, 1999), which both the Liberal Party in Canada and New Labour in the United Kingdom currently have, notwithstanding the recent Liberal leadership change. The second is when substantial change to a particular policy has a high priority within the broader policy agenda of those who command the levers of authority (Tuohy, 1999) so that a commitment to policy change, particularly in a key area like advocacy, must be elevated and sustained by key political actors who, in Canada, would include the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance (Brock, 2002; Johnston, 2002). To date, fiscal and tax policies continue to limit both advocacy activity and charitable registrations, whether they are designed to limit foregone tax revenues or to sustain a cheaper form of public service delivery (Johnston, 2002; Phillips, 2002). The silver lining in this cloud is that, while the durability of the forces that create the policy window will determine its success, the type of response is likely to be shaped by the “fit” between prevailing policy options, such as the paper by the Voluntary Sector Initiative’s (VSI) Advocacy Working Group or the IMPACS report on charities and advocacy, and the internal [bureaucratic] logic of the system it addresses (Tuohy, 1999; Harvey, 2002; IMPACS, 2002).

Further, such policy changes are set in motion by factors external to voluntary sector policy per se, so it is important to realize that a policy window of opportunity arises independent of policy ideas that may be in circulation (Kingdon, 1995). We see an example of such a policy window in the United Kingdom, with Prime Minister Blair’s commitment to “mainstreaming” the role of the voluntary sector in the delivery of public and quasi-public services and his commitment to public-private partnerships and charity reform within the context of his communitarian “Third Way” policy agenda (Giddens, 1998; Blair, 2002).

The Political Stream

The political stream, independent of problem recognition or policy proposals, flows with its own dynamics and rules. Pending retirements, leadership changes, provincial and/or federal elections, and external socio-economic pressures can all foster a political climate that is conducive to change or retrenchment (Kingdon, 1995). However, in a broader context, most of the factors that structure relationships in civil society are, and will likely continue to be, determined by historical and sociocultural factors and the political dynamic within individual countries (Deakin, 2001).

The historical contrast between the United Kingdom and Canada, which, in the latter case, has a much shorter and much less turbulent political and social history, is a case in point. The United Kingdom’s Compacts all acknowledge their history, one in which citizen’s rights have been hard won and are due, in no small part, to the contribution of voluntary organizations (Kendall & Knapp, 1996). Social compacts in Canada, on the other hand, like medicare in the 1960s, largely evolved through the political arena via negotiations with professional bodies, leaving a peripheral role for voluntary organizations as social policy advocates (Brooks, 2001). Thus, the voluntary sector in Canada, unlike its counterpart in the United Kingdom, has far fewer outstanding political IOUs– a situation that influences not only what and when agenda items are tabled, but also how the bargaining process evolves (Kingdon, 1995; Johnston, 2002).

A critical ingredient in the political mainstreaming of the voluntary sector in the United Kingdom was the contribution of influential internal political advocate Alun Michael, M.P., and external policy entrepreneur Nicholas Deakin (Kendall, 2000).

Deakin’s report, supported by and grounded in an extensive sectoral consultation, was seen by New Labour as complementary to its overriding communitarian political philosophy and policy, including its own report, Building the Future Together. This report outlined New Labour’s policy for a new partnership between government and the voluntary sector and stated, among other proposals, that “we seek a diverse but inclusive society … promoting civic activism as a complement to modern government … The Third Way… recognises the need for government to forge new partnerships with the voluntary sector” (Blair, 1998, quoted in Kendall, 2000).

Michael, who led New Labour’s review of the voluntary sector prior to New Labour’s election and wrote Building the Future Together, became the minister responsible for the voluntary sector after the election. This resulted in not only a high political profile for the sector, and ultimately the signing of the Compact between the government and the voluntary sector (please see “The Labour Government’s Compact with the Voluntary Sector,” p. 220), but also a substantial increase in the sector’s financial, human and political resources (Kendall, 2000).

It should be stressed here that the United Kingdom’s political climate is no less dynamic than federal-provincial relations in Canada. Scotland deliberately held off agreeing to a Compact until a Labour government was assured, as devolution was at the heart of New Labour’s proposals. As the annual United Kingdom Compact reports indicate, there is continuing resistance both within particular local authorities and certain state ministries. There is still a long way to go (McIntosh & Dewar, 1998; Carrington, 2002; Deakin, 2002b; Eagle & Stow, 2002).

United Kingdom: The Labour Government’s Compact with the Voluntary Sector (1998)

Principles:

• An independent and diverse voluntary and community sector is fundamental to the wellbeing of society.

• In the development and delivery of public policy and services, the government and the sector have distinct but complementary roles.

• There is value added in working in partnership toward common aims and objectives.

• The government and the sector have different forms of accountability but share a common need for integrity, objectivity, openness, honesty and leadership.

• Government’s undertakings are:

• To recognize and support the voluntary sector’s independence.

• To take account of recommendations for greater funding stability and transparency.

• To consult with, and appraise the sector of, issues which are likely to affect it.

• To promote mutually effective working relationships.

• To develop, in consultation with the sector, codes of good practice.

• To review the operation of the Compact annually.

• Voluntary Sector undertakings are:

• To maintain high standards of governance and accountability.

• To respect the law.

• To ensure users and other stakeholders are consulted both in presenting a case to government and developing management of activities.

• To promote mutually effective working relationships.

• To implement best practice and equality-of-opportunity policies.

• To review the operation of the Compact annually.

Source: Excerpts from Compact: Getting it Right Together—Compact on Relations

Between Government and the Voluntary Sector in England, Home Office (1998)

Canada: The Liberal Government’s Accord with the Voluntary Sector (2001)

• Interrelated values most relevant to the relationship between the Government and the voluntary sector are democracy, active citizenship, equality, diversity, inclusion and social justice.

Principles:

• The independence of voluntary sector organizations includes their right, within the law, to challenge public policies, programs and legislation and to advocate for change.

• Advocacy is inherent to debate and change in a democratic society.

• The actions of one can directly or indirectly affect the other, since both often share the same objective of common good, operate in the same areas of Canadian life, and serve the same clients.

• Each has complex and important relationships with others, including governments and the private sector.

• Both recognize the importance of sustained dialogue and that co-operation and collaboration strengthen the social fabric of communities and increase civic engagement.

• Mutual accountability for maintaining public trust and confidence by ensuring transparency, high standards of conduct, management, monitoring, and reporting.

Government undertakings are:

• To consider the impact of legislation, policies and programs on the voluntary sector.

• To engage the voluntary sector in open, informed and sustained dialogue.

• To address the issue of ministerial responsibility.

• Voluntary Sector undertakings are:

• To identify and act or bring to the attention of the government, important or emerging trends in communities.

• To serve as a means for the full scope, depth, and diversity of the sector to be heard and engaged.

Joint undertakings are:

• To monitor the Accord and report to Canadians.

• To develop codes of good practice (e.g., policy, funding).

• To meet regularly to discuss the results of the Accord.

• To increase awareness of the Accord within the sector and the Government and among all Canadians.

Source: Excerpts from An Accord Between the Government of Canada and the

Voluntary Sector, Voluntary Sector Task Force, Privy Council Office (2001)

In contrast, the Broadbent Report, while acting as a catalyst to the VSR, the VSI, and for the Accord signed in 2001 (see “The Liberal Government’s Accord with the Voluntary Sector,” p. 221) has not been harnessed to a “Third Way” political agenda: the mainstreaming of the voluntary sector in relationship to the delivery of public services, social policy development, the legitimate role of advocacy, or the role of civil society (CCEW, 1997; Larose, 2000; Phillips, 2001).

While the jury is still out on the full extent of the political commitment to, and status of, the voluntary sector in Canada, a Throne Speech did commit the government to putting the Accord into action in order “to enable the sector to contribute to national priorities and represent the views of those too often excluded” (Clarkson, 2002). Further, notwithstanding the recent appointment of a Minister of Social Development (Martin, 2003) who is also responsible for the voluntary sector initiative, the sector has yet to benefit from a dedicated and high ranking political advocate. Only time will tell if this appointment marks the beginning of an increased political awareness and understanding of the issues and priorities of the voluntary sector in Canada.

It may take some time. The professional-collegial nature of government-voluntary sector relations, exemplified by the VSI joint tables, has resulted in an initial shift, or perhaps more accurately, a policy drift, in the historic federalvoluntary sector decision-making culture. This professional collegiality also means that because consensus is the prerequisite to agreement, the rate of change is incremental at best (Tuohy, 1999; Johnston, 2000). This process also requires a great deal of trust and moral suasion (Phillips, 2002), which, in the absence of a sustained political and policy shift, is vulnerable to changes in leadership. Key to success will be the nurture of policy entrepreneurs, political advocates, and a broad constituency both inside and outside government, and a voluntary sector poised and ready to take action when the policy window opens wide enough to sustain change.

Conclusion: Observations and Challenges

1. History Does Make a Difference

The United Kingdom experience with the voluntary sector is a long one, while Canada’s is relatively short. Political changes in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were preceded by civil action and supported through voluntary agencies. What, on the other hand, will Canada’s voluntary sector legacy be in relationship to social inclusion, democratization, protection of the vulnerable, and social justice?

2. We Must Look for the Political Window of Opportunity

If the problem and policy streams converge with the political stream, to what extent will the voluntary sector in Canada be willing and able to collectively become a player in the politics of policy development beyond bureaucratic collegial relationships? Canada is facing a number of leadership and power changes and we must prepare now for the future when policy windows open.

3. We Must Hold a Future Vision

The research, policy, management, and networking capacity of the voluntary sector in Canada is growing by leaps and bounds. Volunteers and voluntary organizations in communities, cities, and provinces across Canada are waking like sleeping giants. So too, in time, will politicians. The voluntary sector in Canada must embrace even greater commitment to furthering its own legitimacy, diversity, purpose, and voice.

REFERENCES

Bennett, C. (2002). Cross-country check-up. CBC Radio Broadcast, Toronto: Canadian

Broadcasting Corporation.

Blair, T. (2002). Private action, public benefit: A review of charities and the wider not-forprofit sector. London: Strategy Unit.

Broadbent, E. (1999). Building on strength: Improving governance and accountability in Canada’s voluntary sector. Ottawa: Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector.

Brock, K. (2002). Public policy and the nonprofit sector: New paths, continuing challenges. (unpublished).

Brooks, N. (2001). The role of the voluntary sector in a modern welfare state. Retrieved

November 13, 2001, from <http://www.nonprofitscan.org/state-and-markets>. Carrington, D. (2002). The compact the challenge of implementation. Retrieved October 18, 2002 from <http://www.ncvo-vol.org.uk/main/gateway/compact.html#monitoring>.

Charity Commission for England and Wales. (1997). Political activities and campaigning by charities. London: Author.

Chretien, J. R. H. (2002). Prime Minister appoints minister responsible for the voluntary sector. Retrieved October 8, 2002 from <http://pm.gc.ca/default.asp?Language= E&Page=newsroom&Sub=NewsReleases&Doc=voluntarysector_20021008_e.htm>.

Clarkson, A. H. (2002). Throne speech to open the thirty-seventh session of the House of

Parliament. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

Deakin, N. (2001). Putting narrow-mindedness out of countenance—The UK voluntary sector in the new millennium. In H. K. Anheier & J. Kendall (Eds.), Third sector at the crossroads: An international nonprofit analysis (pp. 36–50). London: Routledge.

Deakin, N. (2002a). (personal communication, June 6, 2002). Deakin, N. (2002b). (personal communication, October 10, 2002).

Eagle, A., & Stowe, K. (2002). Report of the second annual meeting to review the Compact between ministers and representatives from the voluntary and community csector. London: Home Office/ Compact Working Group.

Giddens, A. (1998). The third way: The renewal of social democracy. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. Harvey, B. A. (2002). Regulation of advocacy in the voluntary sector: Current challenges and

some responses: Prepared for the Advocacy Working Group. Ottawa: Voluntary Sector

IMPACS. (2002). Let charities speak: Report of the charities and advocacy dialogue.

Vancouver: IMPACS—Institute for Media, Policy, and Civil Society and Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

Johnston, P. (2000). Lessons learned. Presented at the 2000 Independent Sector Annual

Conference Pre-Session, Building Global Democracy & Civil Society, Washington, DC. Johnston, P. (2002). (personal communication, September 21, 2002).

Kendall, J. (2000). The mainstreaming of the third sector into public policy in England in the late 1900s: Whys and wherefores: Civil Society Working Paper 2. London: London School of Economics, Centre for Civil Society.

Kendall, J., & Anheier, H. K. (1999). The third sector and the European Union policy process:

an initial evaluation. Journal of European Public Policy, 6(2), 283–307.

Kendall, J., & Knapp, M. (1996). The voluntary sector in the UK. Manchester: Manchester

University Press.

Kingdon, J. W. (1995). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. New York: Harper Collins

College Publishers.

Klein, R. (1991). Risks and benefits of comparative studies: Notes from another shore.

Milbank Quarterly, 69(2), 275–291.

Larose, G. (2000). The community network: A key player in Québec’s development: Summary of the consultation document. Retrieved September 9, 2002 from <http://www.mess. gouv.qc.ca/anglais/saca/polrecsaca.htm>.

Martin, P. (2003). Federal cabinet. Government of Canada. Retrieved December 12, 2003, December 12, 2003, from www.gc.ca.

McIntosh, N., & Dewar D. (1998). The Scottish Compact: The principles underpinning the relationship between government and the voluntary sector in Scotland. London: Secretary of State for Scotland.

National Council for Voluntary Organisations. (1996). Meeting the challenge of change: Voluntary action into the 21st century. London: Author.

Phillips, S. (2002). Voluntary sector-government relationships in transition: Learning from international experience for the Canadian context. In K. Brock & K. G. Banting (Eds.), The nonprofit sector in interesting times: Case studies in a changing sector (pp. 17–70). Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Phillips, S. D. (2001). A federal government—voluntary sector accord: Implications for Canada’s voluntary sector. Retrieved March 11, 2002 from <http://www.vsi-isbc.ca/ eng/joint_tables/accord/pdf/phillips.pdf>.

Straw, J., & Stowe, K. (1998). Compact: Getting it right together—Compact on relations between government and the voluntary sector in England. London: Secretary of State for the Home Department.

Tuohy, C. H. (1999). Accidental logistics: The dynamics of change in the health care arena in the United States, Britain and Canada. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Voluntary Sector Initiative. (2002a). National survey of voluntary organizations begins.

Update—Voluntary Sector Initiative, March, 2002(10).

Voluntary Sector Initiative. (2002b). Statistics Canada project gets secure funding for research on voluntary sector effort. Update—Voluntary Sector Initiative, February, 2002(9).

PETER R. ELSON

Policy and Research Consultant, Toronto, Ontario

The author wishes to acknowledge, with thanks, the helpful comments of Nickolas Deakin and Jeremy Kendall of the London School of Economics and Political Science in the preparation of the original paper.