Viewpoint expresses the particular view of contributors and does not necessarily reflect the views of The Philanthropist. Readers are invited to respond to articles in this section. If appropriate, their views will be published.

This article will not be about the regulation of charities in an ideal society. In a ideal society there would be no need for charities. Nevertheless, while we wait for Utopia, there is no reason we cannot consider, discuss and suggest “ideal” methods for regulating charities and their activities in Canada.

For a variety of reasons, and particularly because charities, and those who make donations to them, are given certain concessions with respect to taxation at various levels, it must be conceded that some regulation of charities is essential. The questions I propose to address are “how?”, “how much?” and “by whom?”

So far as I am aware, Ontario is the only province which actively concerns itself with the administration and regulation of charities and, while I strongly approve of the aims and objectives of the Ontario Public Trustee and agree that many beneficial results are obtained from the methods used in Ontario, I believe that individual provincial charitable registration is inappropriate. Should other provinces follow Ontario’s lead, it would mean that nation-wide charities would have to comply with 11 (or 13 if you count the Territories) different sets of legislation and rules.

I accept that, from a constitutional point of view, property is a provincial concern and that most charitable activities relate to property. Despite this, I am of the view that there should be only one set of rules with which any charity must comply and that set must be imposed by the federal government. Since many of the tax concessions made to philanthropy are granted under the federal Income Tax Act, it might well be that the existing federal method of regulation can be suitably extended. Of course, any exemption from realty and sales taxes, which are within the jurisdiction of an individual province, must be considered and accomplished under provincial legislation and, assuming that the federal government and the provinces could agree, this is the one case where it would be necessary to encourage all of the provinces to enact similar legislation.Present Federal Registration Under the present federal system, the requirements for initial registration constitute the main aspect of regulation insofar as it relates to the activities carried on by any individual charity. After registration has been completed, provided that the charity files the required income-tax returns (on which I will comment later) and provided that these returns do not disclose any serious irregularities, the registration of the charity will normally be continued.

In order to become a registered Canadian charity, an applicant must file details of its organization and activities (either existing or proposed) including fund raising, administration, expenditures, etc. In general, very few inquiries appear to be made about the actual activities (either present or proposed) of the applicant. It may well be that investigations are carried out, but I have not been made aware of any such investigation of any client for whom I have made application and it seems unlikely that my clients have, unknown to them, received some special dispensation.

Proposed Changes to Federal Registration and Regulation Procedure I suggest that the present system under which an applicant can become a registered Canadian charity be changed so that registration can be accomplished in a relatively short time. Reporting requirements should then be increased to enable investigations of the activities of the registered charities to be made and suitable regulatory action taken where appropriate.

Some of the matters which might be considered in order to accomplish more adequate federal regulation are:

1. Registration

As stated above, registration should be completed in a very much shorter time than is now the case. This would enable charities to become organized, receive donations for which they can give appropriate receipts, and commence operations. Under the present system, a charity can become organized and receive donations but does not know for some time whether it will be able to provide its donors with tax receipts. Yet it is usually extremely difficult for a charity to generate any donations at all until it can give assurance that the donations will be deductible.

2. Regulation

The regulation of registered charities after registration should be restructured so as to be much more effective than it is at present. Some of the steps which might be taken are as follows:

(a) Each registered charity should be required to file an audited financial statement within (say) three months after the end of its fiscal year. The form of this statement should be the subject of negotiation between Revenue Canada and the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants so that the statement will disclose all the information required for effective

regulation. I recognize that the requirement for a formal audited statement could result in hardship for small charities and it might be that a charity which received donations totalling less than some arbitrary figure would be permitted to file a statement prepared by someone (perhaps even some internal official) who is not a chartered accountant.

(b) Each charity which received donations totalling more than the above arbitrary figure would have to appoint an Audit Committee made up of persons who were not employees or officers of the charity. Members of the Committee might all be directors of the charity but I suggest that at least one person should be unconnected (except perhaps as a donor) to the charity.

(c) All charities should be required to meet a suitable disbursement quota with respect to the funds which they receive and for which they give charitable receipts and (as discussed below) possibly the net income from any business carried on by that charity. It is hoped that the method of calculating the disbursement quota might be somewhat simplified from that set out in Section 149.1 ( 1) (e) of the present Income Tax Act.

(d) A procedure should be developed under which anyone who could establish to the Federal Court of Canada a prima facie case that the financial affairs of a charity should be reviewed could bring an application before the Federal Court for an accounting. To avoid the possibility ofharrassment or heavy expenses to the charity both for legal costs and the accounting costs of preparing the required documents for submission to the court, it might be possible to establish a procedure under which:

i) if the Court found that the affairs of the charity were in order, the applicant who had demanded the accounting would be required to pay all the costs of the application; or ii) if the Court found that the affairs of the charity were not in order, the charity would be required to pay all of the costs of the application.

3. Returns

To make point 2 feasible, all registered charities should be required to file annual returns which should (except, as previously noted, in the case of small organizations) include audited financial statements and whatever information is necessary to enable Revenue Canada to satisfy itself that the financial affairs of the charity are in order. I see no reason why the returns filed with Revenue Canada should not be available for inspection by anyone.

4. Deregistration and Its Effect

There are a number of reasons for which the registration of a charity might be cancelled, including:

(a) Financial impropriety found as a result of the type of court application referred to above or as a result of a departmental investigation;

(b) Partisan political activity which would mean supporting (financially or otherwise) a particular political party rather than endorsement of one or more aspects of the platform of a party. I applaud the intimation in Resolution 63 of the May 23, 1985 Budget and the subsequent Background Statement of the Minister of National Revenue that non-partisan political activity by a registered charity will be permitted-this legitimizes what has been going on for many years;

(c) Failure to file returns when required. As is the practice now, this penalty should only be invoked after suitable warnings;

(d) Failure to meet the appropriate disbursement quota for (say) two years; and

(e) Fund-raising methods which are clearly inappropriate or improper this would include coercion (of whatever kind) and promises of benefits to the donor (except, of course, the satisfaction of making a donation to a worthy cause).

In my view, the current provisions relating to the effect of cancellation of registration are satisfactory but it would seem more constructive if charities whose registration was cancelled were to have the option of donating their assets to a registered charity of their choice rather than, as is currently the case, having them taken as tax. It must be made clear that all cancellations of registration will be subject to appeal, first to the Minister and then to the Federal Court and that a successful appeal will result in reinstatement of registration retroactive to the date of cancellation.

Businesses Carried On by Charities

The Income Tax Act as it applies to charities now allows a charity to carry on a related business and then (in one of its usually unusual definitions) provides that a related business includes an unrelated business if substantially all of those people “employed” by the charity in carrying out that business are not paid for such “employment”. Leaving aside the problem of how someone can be “employed” and then not paid, in my view, there should be further consideration given to the carrying on by a registered charity of business activities.

My opinion is that, subject to the comments which follow, charities should not be restricted in any way from carrying on business enterprises. Anyone who has had experience with charities knows that most of them are chronically short of the funds necessary to carry out their charitable activities. One factor in the difficulty charities experience in tradjtional fund raising has been the vastly increased role of various levels of government in areas that were formerly considered the responsibility of private philanthropy. This has given rise to an expectation that “they”, i.e., government, will take care of any necessary or desirable “charitable” activities such as the relief of poverty, health care,education, etc. While most people would agree with the statement that charities can make more efficient use of each dollar they receive than can the government among other reasons, because of the large amount of volunteer talent they command-nobody does volunteer work for the government.

Some of the ways in which businesses carried on by charities might be regulated are:

(a) No part of any other income of the charity could be used to subsidize the operations of the business. This would mean that all such businesses would have to be self-sufficient (except possibly for some fixed start-up period). This might necessitate a new definition of”business” because obviously operations by a charity which are designed to further its charitable activities (such as sheltered workshops, training schools, etc.) might never be able to be self-sufficient; and

(b) The net income of any such business should be subject to the same disbursement quota as funds received by the charity for which it gives charitable receipts. This would mean that “net income” would have to be suitably defmed so as to allow the business to operate and to establish appropriate reserves, having regard to the type of activities it carried on.

The result of the foregoing might well be that there would still be “related” and “unrelated” businesses. The related businesses would not be subject to the disbursement quota nor would there be any restriction on the use of the other funds of the charity to support any such related business. Perhaps a procedure could be established by which a charity could receive an advance ruling as to whether a business was related or unrelated.

Volunteer Time

The question of allowing charities to give receipts for volunteer time is one which it may be impossible to resolve. There have been suggestions that all volunteer time should be valued at the minimum wage applicable at the time but it seems to me that this is, at best, unsatisfactory and, at worst, an insult to many volunteers. For example, consider the situation with respect to chartered accountants who spend many hours as volunteer treasurers for charities.

Any procedure by which the value of volunteer time could be recognized by the giving of receipts might be very difficult to administer. The charity would have to keep an accurate account of the hours spent (many of which would be spent independently by the volunteer so the charity would have to accept the statement of the volunteer that such time was spent) and would have to establish a value for each such hour. There are many people who engage in voluntary activities on behalf of charities and without whom many charities could not operate.It may well be that the difficulty of administering a system under which credit was given for volunteer hours would outweigh any benefit to any volunteer. It is also possible the benefit of any receipt given would only be of appreciable value to a volunteer with a substantial income and then, probably only if (as I suggest below) the ceiling above which charitable donations are not deductible were to be removed.

Benefits to Registered Canadian Charities

1. Receipts

Each registered Canadian charity should, as now, have the privilege of giving receipts for donations and the recipients of these receipts should be allowed a suitable deduction from taxable income or tax payable.It is, perhaps, an anomaly that the taxpayer receives a more substantial benefit from making a donation to a political party than is received for a donation of the same amount to a registered Canadian charity. It is my belief that charities are of more benefit to society than are political parties but that is not, perhaps, a universal view. I suggest that the 20- per-cent limitation on the deduction of charitable donations be removed. I doubt that, if the limitation were removed with respect to gifts intra vivos, it would make any substantial difference in the total amount of tax collected by Revenue Canada but it would encourage increased charitable donations and, as I have said, since I believe that charities in general make much more efficient use of their funds than do government agencies doing the same work, this should make it possible for governments to reduce some of their commitments. If the 20-per-cent limitation were completely removed, then the taxes payable by the estate of a deceased taxpayer might also be substantially reduced but, here again, since the charities, in general, make much more efficient use of funds than does any level of government, and since the object of allowing any deductions is to encourage charitable donations, the net result to society would be beneficial.

2. Federal Sales and Excise Taxes and Customs Duties

All items imported into Canada by any registered Canadian charity which can establish that such items are to be used in connection with its charitable activities or in connection with any related business should be free of all customs duties and excise taxes. Any goods purchased in Canada for any similar purpose should be free of all federal sales taxes. On the other hand, any goods imported or purchased by a registered Canadian charity for use in connection with an unrelated business should be subject to all appropriate federal taxes and duties.

3. Property Taxes and Provincial Sales Taxes

In order to establish a uniform method of imposing these taxes, it would probably be necessary for the federal, and all provincial governments, to reach agreement

(at least in principle). I suggest that all property owned or leased by a registered Canadian charity and used by it for its charitable activities or that of any related business should be exempt from provincial or municipal taxation. However it would not be inappropriate for premises owned or occupied by any unrelated business to be subject to municipal taxation. The same principle should apply, in general, to provincial sales taxes-at present there are some limited exemptions in some of the provincial sales tax statutes but these might well be extended.

4. Income Tax

The present exemption of any charity from the payment ofincome tax should, of course, be continued. It might well be that if an unrelated business did not meet the appropriate disbursement quota in any year there should be an imposition of income tax on the amount by which it failed to reach such quota.

Operations Out of Canada

As the system is now administered, a registered Canadian charity can only expend

funds outside of Canada if it keeps control over those funds and if it continues to own any capital assets purchased with them. In some cases, this results in a rather artificial system under which the Canadian organization appoints someone in the recipient country to be its agent and to own assets on its behalf, although in fact, the decisions as to what is to be done with the funds are made entirely in the recipient country. It can be argued that some control should be kept over funds which are sent out of Canada but perhaps the position could be taken that, if a charity is a registered Canadian charity in good standing, then it should be allowed to decide whether its funds are to be used in Canada or out of Canada and, if out of Canada, it should be allowed to give its funds to any organization it selects or to delegate to anyone it selects the power to decide how the funds are to be employed. A number of years ago it was considered acceptable for our (then paternalistic) organizations to do whatever or buy whatever they thought appropriate for the recipient countries but this procedure is no longer appropriate.

Foundations

I have no suggestions of substance to make with respect to the present regulation of foundations. It appears to me appropriate to continue the distinction between private and public foundations and also to provide that private foundations may not carry on any business whatsoever. I suppose that it is always possible that an argument could be made for allowing an organization to be both a public foundation and a charitable organization but it seems to me that the administration (and especially the accounting procedures) of any such organization would be unacceptably complex and, therefore, no such hybrid organization should be permitted. (An exception could be made for charitable organizations with endowment funds.)

Non-Profit Organizations

There are a large number of organizations in Canada which may or may not be “charitable” in the common law sense but which are clearly for the general benefit of the public and which do not wish to become registered Canadian charities. It would be appropriate to regulate these organizations in some way and I suggest the following:

Registration

They could apply for registration with Revenue Canada and become registered non-profit organizations. The result of this registration would be that they would be free of income tax although they could not issue charitable receipts and would probably not be exempt from customs duty, excise taxes and federal excise taxes. They might, if they were within the common law definition of a “charity”, be exempt from municipal taxes and provincial sales taxes. Under the provisions of Section 149.1(1) of the Income Tax Act a “non-profit organization” is one which the Minister has determined is not a “charity”. In my view, this means that, under the present legislation, the only “non-profit organizations”are those which have applied to become charities and have had their applications refused. This is clearly a ridiculous situation and must be changed.

Incorporation of Charities

It is my opinion that all charities should incorporate and, possibly, should be required to incorporate, under the appropriate federal or provincial statutes.Inmost cases, the statutes should be amended so as to give charities (and non-profit corporations) the benefit of some of the provisions of the appropriate statutes governing business corporations such as:

a) Telephone meetings (at least of directors);

b) The possibility of signing resolutions rather than holding meetings. This would be particularly helpful in the organizational stages;

c) A board of directors of a size variable within limits stated in the incorporating documents; and d) Suitable provisions for exemption with respect to proxy solicitation, etc.

It might also be appropriate to provide that the members of any charitable or nonprofit corporation could vote by mail rather than being required to complete proxies so that directed proxies would not have to be exercised at the meeting.

Other Organizations

The present provisions of the Income Tax Act which permit deductions with respect to donations made by a taxpayer include references to municipalities, national sports organizations and other bodies. I make no comment on whether such donations should be deductible, but I strongly suggest that the Act be amended so as to separate “real”charities from all others (except foundations).Ifthis were done, the provisions of the Act relating to charities (and foundations) could, I believe, be drawn much more clearly and succinctly and should therefore be easier to understand. I do not understand why donations to municipalities, athletic associations, housing corporations, etc. should be included in the 20-per-cent maximum deduction from incomeassuming that it still existed. Donations to such bodies should be subject to some limitation but surely it is inappropriate to class them with charitable donations.

Conclusion

Obviously my ideas of the “ideal”will not necessarily be shared by others. Still, ifwe all agreed, how dull would it be! I would welcome comments, either for or against, from others with experience in the regulation of charity. Perhaps if we could generate sufficient controversy we would see positive change. In any case, controversy would be a pleasant change from the usual reaction of those outside the charmed circle of this publication, whose traditional reaction to calls for simplification and change in the regulation of charities has been—a great storm of apathy.

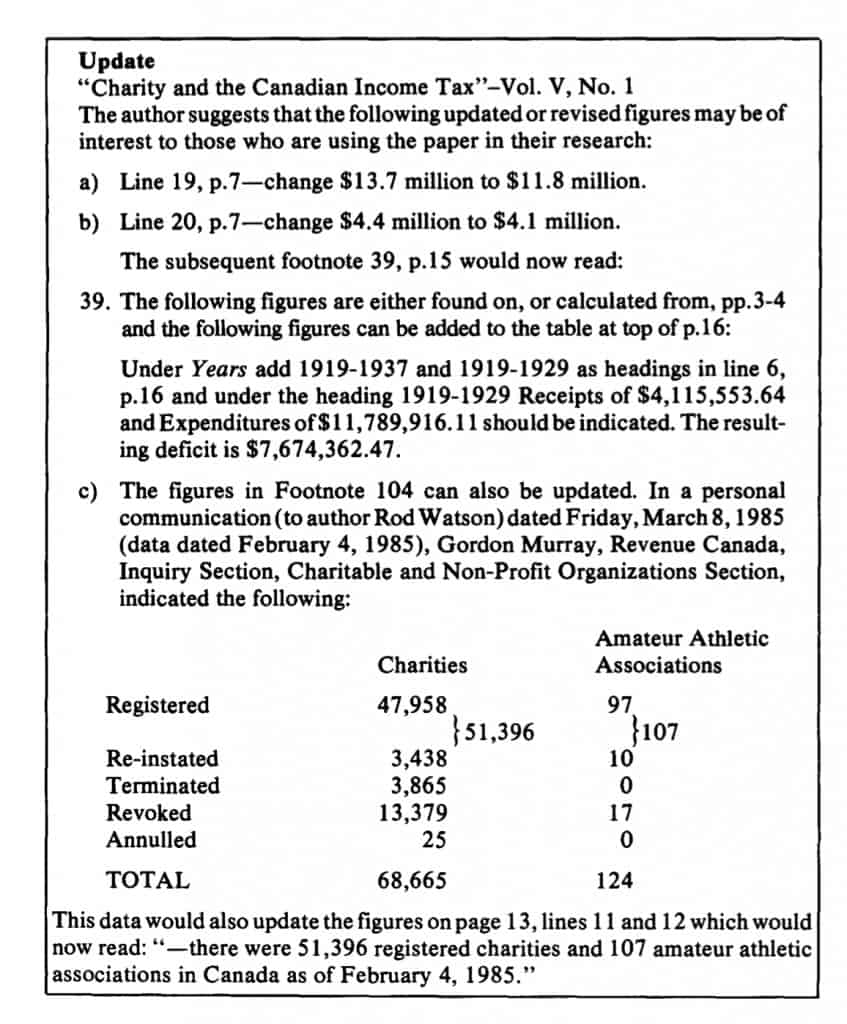

Update (see image)

“Charity and the Canadian Income Tax”-Vol. V, No. 1

The author suggests that the following updated or revised figures may be of interest to those who are using the paper in their research: a) Line 19, p.7-change $13.7 million to $11.8 million. b) Line 20, p.7-change $4.4 million to $4.1 million.

The subsequent footnote 39, p.15 would now read:

39. The following figures are either found on, or calculated from, pp.3-4 and the following figures can be added to the table at top of p.16:

Under Years add 1919-1937 and 1919-1929 as headings in line 6, p.16 and under the heading 1919-1929 Receipts of $4,115,553.64 and Expenditures of$11,789,916.11 should be indicated.The resulting deficit is $7,674,362.47.

c) The figures in Footnote 104 can also be updated. In a personal communication (to author Rod Watson) dated Friday, March 8, 1985 (data dated February 4, 1985), Gordon Murray, Revenue Canada, Inquiry Section, Charitable and Non-Profit Organizations Section, indicated the following:

Amateur Athletic Charities Associations

|

Registered |

47,958 |

} 51,396 |

97 }107 |

|

Re-instated |

3,438 |

10 |

|

|

Terminated |

3,865 |

0 |

|

|

Revoked |

13,379 |

17 |

|

|

Annulled |

25 |

0 |

|

|

TOTAL |

68,665 |

124 |

This data would also update the figures on page 13, lines 11 and 12 which would now read: “-there were 51,396 registered charities and 107 amateur athletic associations in Canada as of February 4, 1985.”

JOHN P. HAMILTON

Member, The Ontario Bar