Addresses to Conference, “The Effective Management and Investment of Charitable Funds” co-sponsored by Oyez Limited and the Canadian Centre for Philanthropy. May 26, 1980

Mortgage Investments for Charitable Foundations

It is probably safe to say that every charitable organization and every charitable foundation is faced with opportunities to spend (and spend productively) a great deal more than its assets and income permit. There is, therefore, an almost unlimited need among such organizations for excellent investment performance to improve income and build up assets. This requires an appropriate investment mix, but (maybe more importantly) it requires extracting the maximum safe return from each investment category.

Specifically, how do you obtain this “best possible” return from the fixed-income sector of your investment portfolio? I am convinced an investor cannot approach that objective unless he is prepared to acquire mortgages whenever that makes economic sense, and that makes sense most of the time, but not all the time. As a rough rule of thumb I suggest that mortgages make sense about 75% of the time while bonds make sense not more than 25% of the time.

A dogmatic statement like that requires some supporting evidence. One part of that evidence is that mortgages usually carry an interest rate I% to 2% per annum higher than bonds. It is easy (but erroneous) to assume that this represents compensation for extra risk. Not so. With well selected mortgages, properly implemented, there is no extra risk. National Housing Association (NHA) mortgages, for instance, are insured by an agency of the Canadian Government and backed by essentially the same credit as Government of Canada bonds. Yet the NHA mortgage yield can be much higher than bond yields.

NHA mortgages are obtainable only on residential property, including houses, apartments, nursing homes and some similar structures. Privately insured mortgages can be obtained on all .types of real estate, but private mortgage insurance probably merits a somewhat lower credit rating than the NHAgovernment-backed insurance. Uninsured mortgages are also available, and some of the best of these are secured against quality real estate which in turn may be backed by leases to major corporations. Mortgages of that quality are as safe as (or sometimes safer than) good corporate bonds.

We have been talking about credit risks, but from an investor’s standpoint price risks may be more significant. As a good many investors now realize, bonds can (and in recent years did) suffer enormous declines in market value while the market values of mortgages declined much more gently. There are good reasons for this. A higher-yielding safe security is logically worth more than a lower-yielding safe security, and eventually market prices tend to reflect intrinsic value. Also, mortgages tend to be shorter in term than bonds, and for this reason suffer less in periods of rising interest rates.

But what if you expect a continued decline in interest rates? Should you not buy bonds in that case? Maybe, if you are absolutely certain of your forecast and if you can consistently make a bond trading profit of about 2% per year on top of the interest return. Many bond lovers had been promising such returns for years, but the love affair tended to sour with the passage of time.

It has been said that one should not try to apply logical thought processes in an illogical investment world, as investments seldom behave in precisely the way that logic suggests. Mortgages, however, do produce the superior returns which one would logically expect.

As evidence, let’s examine the performance of a few hundred Canadian pension funds as reported by the Wood Gundy Comparative Measurement Service.

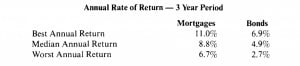

Annual Rate of Return 3 Year Period

For this three-year period (ended December, 1979) the 8.8% median return on mortgages greatly exceeded the 4.9% median return on bonds. In fact the best return on bonds coincided very closely with the worst return on mortgages. While updated figures are not yet available, it is reasonably certain that for 1980, the margin of superiority for mortgages would be even greater.

This is not an isolated occurence. For the ten-year period ending in 1979 the median annual rates of return were:

Mortgages 9.4% Bonds 8.4%

At first sight this is not a huge difference, but it means a good deal when compounded over a ten-year period. An initial investment of one million dollars, at 9.4%, accumulates in ten years to $2,455,000, or $215,000 more than an 8.4% bond investment will produce.

Nowadays, of course, all interest yields are higher, but mortgages continue to offer a margin of superiority over bonds; currently close to 2% per annum. Pension funds and charitable foundations cannot afford to ignore such differentials. Sound investment practice must frown on accepting 13% when you can obtain 15% with equal safety. The difference is larger than it seems: Subtracting about 11% for inflation, do you choose a real return of 2% or 4%?

How do you obtain these superior yields? In general not by buying mortgages “off the shelf’ from trust companies or other institutions. Mortgages bought in this way tend to produce returns little, if any, better than bond yields. To obtain appropriate yields, it is necessary to make commitments before the start of construction of an apartment or other structure, for mortgage money to be advanced during construction or after completion. This can be done through a mortgage broker or an investment counselling firm.

Some investors are unduly concerned about possible problems in mortgage administration or accounting. You do not have to get closely involved in these, because your mortgage servicing agent will handle them. On NHA mortgages you are required to have a servicing agent who has been granted “Approved Lender” status by the Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation. The servicing agent can be a bank, a trust company, or in some cases the mortgage broker who originated the loan. On house mortgages. the usual servicing fee is %%per annum. On larger mortgages such as rental apartments the fee may be1 %, ‘/10 % or sometimes less. The servicing agent collects the monthly payments and remits them to the investor, and looks after such things as seeing that taxes and fire insurance premiums are up to date. (The figures presented earlier on mortgage returns earned by pension funds are net after paying servicing fees.)

The mortgage is normally registered in the name of the servicing agent. If a mortgage gets into arrears and foreclosure is necessary, the proceedings are taken in the name of the servicing agent, so that the investor is shielded from problems such as adverse publicity. On an NHA mortgage, after foreclosure is completed, the servicing agent submits a claim to Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation which provides reimbursement of:

• the mortgage principal;

• interest arrears up to one year at the full mortgage rate plus another six months at 2% below the mortgage rate;

• reasonable legal fees and other expenses necessary in the circumstances.

It is conceivable that if the foreclosure process is long drawn out, the investor may lose a few months’ interest, but the possibility of significant loss is remote. So the risks in mortgage investments, properly managed, are significantly less than in most other investment categories.

Registration in the name of the servicing agent also provides a very convenient and economical way of dividing a large mortgage among two or more investors. Each investor merely contributes his agreed share, and the servicing agent sends him his portion of each monthly payment.

What it boils down to is this: mortgage investment is not as difficult as many investors think, but it is more complicated than buying bonds and takes a little more patience. The point is that you are amply, or more amply, compensated for this slight extra complication. In these inflationary days we cannot afford to throw away such incremental investment returns.

Mortgages need not be a long-term investment. While a five-year term is typical, good investment opportunities frequently occur for terms as short as one or two years. The interest rate may be fixed or may float at a differential over a yard-stick such as bank prime or the rates offered on trust company guaranteed investment certificates.

Conclusion

Inflation is, of course, the great enemy of pension funds and of endownment funds. As you know, there are two ways to cope with inflation:

1. One way, which we tend to overlook, is to obtain a fixed-income yield high

enough to provide a reasonable inflation-adjusted return. If you assume that inflation will continue at somewhere in the general neighbourhood of 11% per year, a safe 15% mortgage is not bad. The return of 4% after inflation is much better than the negative real returns experienced by many fixed-income investors in recent years.

2. The other method of coping with inflation, of course, is to buy investments which can be expected to increase in value, and/or in yield, faster than inflation. This normally means equities, which most people interpret as being common stocks. But equities include real estate ownership and if you own real estate I hardly need to remind you that, over any reasonable period of years, it’s undoubtedly performed even better for you than your common stocks.

For many pension funds and some foundations, revenue-producing real estate can be a logical and rewarding investment. There are, however, legal obstacles and problems of size and of property management.

There is also a competitive problem in that, by reason of capital cost allowances and other tax factors, a property may be worth more to a taxable investor than to a non-taxable institution.

What to do about it? One approach with a proved record of success is a “participating mortgage”. Essentially this is a mortgage negotiated at an interest rate possibly 1% or 2% per annum below prevailing market levels. In return for this reduced interest burden, the owner or developer may give the lender the right to receive a percentage (typically 25% to 50%) of the net cash flow of the property over the term of the mortgage, which can be up to fifty years. Ifthe property is one on which rising income over time can be expected (a shopping centre, for instance), the potential is clearly very large.

Naturally, a developer is not eager to give participation. But if he is faced with the prospect of a negative cash flow, and if the reduced interest rate can convert this into a positive cash flow, his only realistic option may be to take on a participating mortgage. Properly structured, such mortgages can make a great deal of sense to both parties. They take maximum advantage of the non-taxable status of the lender while easing the tax burden and interest burden on the borrower.

In summary, I hope I have conveyed the message that mortgages are safer than you think, higher yielding than you think, and less troublesome than you think. Also, mortgages are more marketable than you may have been led to believe. Mortgages can have more inflation-fighting possibilities than generally realized. You will be hearing about the virtues of well selected stocks, and I fully agree. But please remember, stocks are not the only hedge against inflation. Mortgages can provide an inflation hedge at extremely low risk.

HOWARD M. CUNNINGHAM, Cockfield Cooper Cunningham Investment Counsel Inc.

STEPHEN A. JARISLOWSKI *

The management of a Charitable Fund as far as common stocks are concerned follows most of the benchmark of fiduciary investment. What I am going to say today is not really much different from what I tell trustees of any kind.

First of all the time horizon is essential-If the fund is growing, due to new cash being infused (either income or new donations), then, no doubt, equities have a more ready place in the portfolio, for equities from year to year can and do have very variable returns. A stock can sink 30-40% in a year and be up 40-50% the next year. While at the end of two years this may make little difference, at any one time in those two years trustees may feel quite unhappy. As we normally make our mistakes in investing when we are either happy or unhappy, consequences in the two years may not be propitious for the fund. Needless to say, the less we are perturbed by volatility or variability, the better equity investors we tend to become.

Why equities? Well, simply because, despite their volatility, equities over long periods (25 years and over) have reliably given investors far more return than cash, bonds or mortgages. While volatility is high over short and sometimes medium term (10 years), over very long periods stocks have shown remarkably little volatility. Thus, over long periods, certificates of deposits in the USA have yielded inflation no more no less. Bonds of the 20-year Government variety provided 0.6-1.0% over inflation, while corporates (A quality) gave 1.0-1.5%.

Mortgages are difficult to measure, being largely illiquid in the past, but stocks have given 5-6% real yields. As this is at least five times as much as Government bonds and four times as much as ‘A’ corporates, the incentive to invest in stocks is very great, especially if one has 25-year and over time horizons.

The problem with most charitable funds is that they tend to be overly charitable. They spend their ‘income’. Since ‘income’ includes not only real returns but also the inflation factor, in fact charitable funds, with no exceptions I know, spend far more than their ‘income’-each year they spend capital. What charitable fund invested in only bonds spends but 0.6-1.8% of capital per annum, the perimeters of bond investment? What charitable fund, invested entirely in short-term bank deposits would refuse to part with a nickel? It is only by the use of·equities’, and, specifically stocks, that an asset mix can be determined which allows spending without in fact touching capital. Thus, very long-term, a stock portfolio with a 20% reserve to provide funds in bad times, might yield 3.5-4% real and allow spending of that magnitude without encroachment on capital.

Encroachment on the ·real’ capital is the greatest sin perpetuated by fiduciaries or trustees of charitable funds. They never fail to do so, despite that many have a rule not to encroach on capital. There is no 12% interest-there is only 1Y2% interest (or less) and a balance of inflation. Equities are the only investment medium among those popularly used that may allow you to earn on a 50/50 fixed/income/equity asset mix a 2.5-3% real return. If you so invest you can spend 2.5-3% of average capital over a long period and not need to reduce your spending in real money.

Thence the need for equities – if you can afford the volatility and make provisions that it cannot hurt you-in bad years.

The typical sin is to sell stocks in poor years to provide funds required on an ongoing basis-of course this is precisely the time when you should NOT touch equities and, on the contrary, add to your stock portfolio. A dollar withdrawn from a stock when it sells at $10 is equivalent to withdrawing $2 when it sells at $20. Thus, one should never withdraw from the equities in low markets, never mind the gloomy atmosphere. Taking money out of stocks in low markets is very expensive money. It is, therefore, imperative that reserves be available in endowment funds to draw on in poor markets-funds which are established preferably when stocks are high. Our view is that these reserves should always be in short-term money instruments, readily cashable without any risk of loss.

At this point I want to make explicit something very badly understood. Volatility and risk are only synonymous in the hands of poor investors or emotional people. Volatility is only too often equated with risk-which it is by no means. This is not to say that there is not risk in an individual stock. Of course there is and one need but look at a New York Central or a Chrysler. Individual companies under poor management can and do go bankrupt, making the stock certificate worthless, but this does not happen to the ‘Averages’ or the total stock market. While one stock is declining; another’s fortunes are rising and, of course, the total market has never disappeared, except to Communism or a total political upheaval abolishing capitalism. At such cataclysmic times it matters little whether you have a charitable, endowment, pension or any other fund, for all these are eliminated without much favoritism. As long as we have free enterprise, industrial fortunes will go up and down and values will grow with those of the country and the particular industry in it. Many years of affluence can give way to poor periods, but essentially all industry grows in dollar value with inflation and earnings plow back. In all industrialized, capitalist countries, eventually stock values have followed inflation and this is as it should be, as the net assets of industry consist of inventories and plant, both of which become more valuable in an inflation, or more expensive to replace which means the same. Industrial prices, with long Jags, follow the cost of replacement, based on well tested economic fact. While the particular may often be at variance, the general situation necessarily must become this, or capitalism would cease through mass bankrupty. Volatility is inherent but is not risk per se. It only becomes risk if you invest such that you must sell when prices are low- it is then a risk you yourself have assumed or created, not one inherent in the investments you hold. On the contrary, volatility permits the intelligent investors to reduce the risk of inventory in stocksby buying when stocks are low and selling when they are too high.

Another major detractor from investing in equities is buying and selling. If your aim is a 5% return, very long-term on your equity portfolio, any fees for trading, management, measurement or accounting is a reduction of this 5% return. Of these the most expensive detractor is trading.

The reason why the investors do worse than the averages results from these expenses, in particular from trading. Let’s look at it this way. When you sell a stock to another investor who buys it, the investors together still hold exactly the same stocks-it matters theoretically little whether you or someone else owns it in total. Yet when you sold it you paid a commission—in Canada typically 2% of capital. The buyerpaid a similar 2% for a give-up by the investors to the brokers of 4%. Both the seller and the buyer acted on the view that their trade was justified. In fact, obviously one will be proven as wrong as the other will be shown right. On net the decision is one of absolute vanity in which only the brokers gained. Now a 4% give-up if you sell and then buy back somethingelse(2 X 2%) means that you have jeopardized 80% of the 5% total real return. If you do it twice with the same money in a year on average you guarantee yourself (to total investment community) a cost of 8% or minus 3% for that year in real return.

Trading must be minimized and confined to constrll{;tive policy decisions. When cyclical stocks, for instance, are in an upcycle—they must be sold as they will go down in thedowncycle. If such a stock goes up IOO%fromlowtohighanddown50% to the low —a 4% round-trip commission to something else is justified. A commission is also justified if the odds are that a Company will go broke. Furthermore, initially, a commission is justified, as if held long enough a stock yields far more than a bond. However, when you buy a particular stock, you must be fully aware what you are buying and with what in mind. If the average stock long-term provides 5% from an average market, it will yield more if bought in a below average priced market and less if bought in a high market. If the market is 20% overpriced, it may yield nothing for 8 years while it may go from 20% overvaluation to 20% undervaluation. Conversely, bought in the latter market it could yield on average 10% if the market went to the 20% overvaluation. This is very important and explains the return drought in the USA between 1973 and 1980 on the quality stocks.

As commissions are a percentage of price to a large extent, commissions cost less long-term if you buy in low markets.

The objective of your portfolio is very important. If stocks on average from average markets yield 5%, no doubt there are some that yield more and some less. Cyclical stocks may yield the average if bought in an average market, but their volatility from year to year will be far greater than those of the income or growth variety. However, for most investors they yield less as cyclicals must be sold and so are commission wise expensive.

Income stocks normally yield in total less than non-cyclical growth stocks, for few companies that can earn very high returns on plowed-back income would forego these returns by paying high dividends. Moreover, companies which typically do not reinvest major sums will be left behind by those that do. There are exceptions, but the rule still holds.

The more assured a dividend such as on a public utility stock, the more the long-term real yield will become asymptotic to bond returns, which we know are far less than on the average stock. Also typically, the more stable the income stream, inflation disregarded, the less typical volatility.

To talk of stocks without making the distinction of what kind of stock, what kind of objective and what degree of anticipated volatility is idle talk. Investment programmes should be structured about strategies and policies which know how to win the investment battle, similar to a general who commands infantry, artillery, tanks, cavalry, etc., etc.

In inflationary times, the best mainstay of an endowment fund will be stocks that may keep up or grow faster than the inflation, and at that on a relatively sustainedbasis. When one looks at long-term stock returns, one perceives that the real growth is due to ever-increasing dividends which in turn lead to ever-increasing capital values. Compared with a sustained 4% bond coupon, a stock which can double dividends every five years, starting with a 2% rate will but suffer for the first five years and at year 25 will provide a 64% return contrasted with still but 4% on the bond. Moreover, if never really materially overvalued no trading may be needed in these 25 years, resulting in no dilution from brokerage commissions. Growth stocks can be classified into senior and junior ones-more established companies vs.less established ones. In each case the rate of return on equity capital will be high or in time will become high as it is this reinvestment stream placed at again a high return which brings growth.

No doubt, you should only buy junior growth stocks where you feel very confident that the growth will be far better than in the more conservative growth stock, for a risk must have a reward.

The cyclical stock game is another approach, but there you must sell (too early usually) not to incur a round trip with little to no profit. The income stock approach rarely makes much sense as in Canada dividend tax credits reduce stock market yields from those available on debt instruments.

It is quite clear from the above that stock investment is a must for an endowment fund which wants to spend more than 2% per annum, without dipping in fact into capital. Stock investment requires far greater knowledge and emotional discipline than fixed income investment. In fixed income investment safety of principal, once assured, leaves only term and coupon to be determined. In stocks, term and coupon are unpredictable and an enormous amount of knowledge is required to correctly identify individual common stocks and the follow-up is constant as long as you own the stock. As one 80-year old investor told me: ‘to buy a stock make sure you have excellent management; make sure that it will remain excellent and make sure that it has remained excellent.’ There is much in that, for many fine companies have been wrecked by poor management, while many poor ones have become good under good management. Beyond management, is the present situation of the Company which management can transform, but only in the future, and which it must live with today. This of course is not a speech on security analysis and so I will stop while I am ahead.

STEPHEN A. JARISLOWSKI, Fraser & Company Ltd.. Investment Counsel, Montreal, Quebec.