LAURIE MOOK

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

BETTY JANE RICHMOND

Faculty of Education, York University, Toronto

JACK QUARTER

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Evidence of Volunteer Contributions

In Canada, the National Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating for the year 2000 estimated that there were 6.5 million volunteers (26.7 per cent of the population aged 15 and over) who contributed 1.05 billion hours with a full-time job equivalence of 549,000 (Hall, McKeown, and Roberts 2001). For tasks other than serving on the board of directors, Sharpe (1994) found that about 70 per cent of nonprofits with charitable status used volunteers (about 63 per organization). In other words, while all charitable organizations have a volunteer board of directors, most also have volunteers in other types of service, and some rely heavily on volunteers.

Data from the United States for the year 2000 indicate that 44 per cent of adults over the age of 21 (83.9 million) volunteered with formal organizations and contributed a total of 15.5 billion hours. That amount of service was equivalent to over 9 million full-time positions (Independent Sector 2001a). In the United Kingdom, there were 16.3 million volunteers in nonprofits in 1995 with a full-time equivalence of 1.47 million positions or 6.3 per cent of the paid labour force (Kendall and Almond 1999).

These patterns are similar to those discerned by Salamon et al. (1999) in their study of 22 countries, which found that 28 per cent of the population, or 10.6 million full-time equivalents, volunteered. In those countries, volunteers represented 56 per cent of the workforce of nonprofits, i.e., for every two hours of work by paid employees in nonprofits, volunteers contributed more than one hour. These surveys indicate that volunteer contributions are important to religion, education, social services, recreation, sports and social clubs, and health organizations. Informal volunteering (outside a formal organization framework) is also a major form of service.

Issues Involved In Measuring Volunteer Contributions

In estimating the value of volunteer contributions, there are two general approaches. The first is based on what economists refer to as “opportunity costs”. This label is derived from the assumption that “the cost of volunteering is time that could have been spent in other ways, including earning money that could, after taxes, be spent on desired goods and services” (Brown 1999, 10). Because time might have been spent generating income, the opportunity cost is tied to the hourly compensation that volunteers normally receive from the paid jobs that they hold. However, this procedure raises problems because the skills associated with a volunteer service may differ substantially from those for which a salary is being received (Brown 1999). The hourly rate that Bill Gates receives from Microsoft for his services would not be an appropriate standard if he were to spend a day volunteering at a local food bank. An opposite problem might arise if the food bank volunteer were unemployed and therefore without an hourly wage; it would be incorrect to suggest that the service is worth nothing. After considering the complexities of estimating opportunity costs, including the portion of a paid worker’s hourly wage that goes to taxes, and after adjusting for any fringe benefits, Brown (1999, 11) suggests that volunteer time “be valued at roughly one half to six sevenths of the average hourly wage”. In her view, higher values should be applied when volunteers have increased responsibilities relative to their paid work and that lower values should be applied to the opposite circumstance.

Variations of Brown’s procedure for estimating the opportunity costs of volunteers were undertaken by Wolfe, Weisbrod, and Bird (1993) and Handy and Srinivasan (2002). Wolfe et al. estimated the marginal opportunity costs by asking volunteers what they would have received if they had worked additional hours for pay. Volunteers not in the labor market (retired, students, unemployed) “were asked what they believed they could earn if they decided to seek paid employment” (1993, 31). Handy and Srinivasan (2002) also asked volunteers to estimate how much their tasks were worth, thereby arriving at a lower figure than the marginal opportunity cost.

These procedures vary, but they share the common feature of looking at the value of volunteering from the perspective of the volunteer and at what an hour is worth to the particular volunteer. They differ from the approaches that use “replacement costs” and thereby evaluate the cost of volunteers from the perspective of the organization, if it had to pay the market rate for such a service. Most of the research that estimates the value of volunteers, including our own work, calculates replacement costs. There is a debate as to whether volunteers substitute for paid labor by doing jobs that would otherwise require compensation or whether they supplement paid labor (Brudney 1990; Ferris 1984). However, the replacement-cost framework sidesteps the issue and assumes that volunteer functions should be calculated at the value for similar services in the labor market.

Replacement costs are calculated by various methods. Many organizations estimating the value of volunteers simply calculate a gross average based on the average hourly wage in a jurisdiction. For example, Independent Sector—an advocacy organization for nonprofits in the United States—uses the average hourly wage for nonagricultural workers published in the Economic Report of the President plus 12 per cent for fringe benefits (Independent Sector 2001, 2002). For Canada, Ross (1994) suggested a weighted average of hourly and salaried wages based on Statistics Canada data for employment earnings. He also calculated both national and provincial averages.

However, the predominant trend for applying replacement-cost estimates to volunteers is to base the calculation on the type of service (Brudney 1990; Community Literacy Ontario 1998; Gaskin 1999; Gaskin and Dobson 1997; Karn 1983). For example, Community Literacy Ontario uses an hourly rate for volunteer literacy workers based on a survey of the average annual salary of full-time support staff of 94 community organizations that supply training. The Volunteer Investment and Value Audit (VIVA), developed in the United Kingdom, uses market comparisons based on both the job titles and the component parts of the jobs (Gaskin 1999; Gaskin and Dobson 1997).

One criticism of using replacement costs is that volunteers may be less productive than paid labor and therefore replacement costs could overestimate the value of their contributions (Brown 1999). Another criticism is that organizations that use volunteers are often under financial constraints and, if volunteers are unavailable, they simply reduce the level of service (Handy and Srinivasan 2000). Also, market rates for similar jobs might not evaluate properly the contribution of volunteers who might bring higher levels of skill than the volunteer task requires (Brown 1999).

Financial Statements and Volunteer Contributions

In general, accounting regulatory bodies have been restrictive about the circumstances under which they allow for including estimates for volunteer contributions within financial statements but, when they do, they have favoured replacement costs. The Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants has followed the pattern of the Financial Accounting Standards Board in the United States. In a 1978 ruling, the FASB enunciated four criteria for inclusion: the amount is measurable; the organization manages the volunteers much like its employees; the services are part of the organization’s normal work program and would be paid for otherwise; and the services of the organization are for the public rather than its members. These criteria, embraced by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (1980) were quite restrictive and excluded the services that members donated to nonprofit mutual associations such as religious organizations, clubs, professional and trade associations, labor unions, political parties and fraternal societies.

A 1993 United States update (FASB 116) has the same restrictive character: “Contributions of services are recognized only if the services received (a) create or enhance nonfinancial assets or (b) require specialized skills, are provided by individuals possessing those skills, and would typically need to be purchased if not provided by donation” (Financial Accounting Standards Board 1993, 1). March 1996, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants released a special set of accounting standards for nonprofits (Sections 4400–4460), effective for fiscal periods beginning on or after April 1, 1997. These standards were largely adaptations of those applied to business enterprises, focussing on profit and loss, and sidestepping the unique characteristics of social organizations.

Even though accounting regulatory bodies allow for the inclusion of volunteer hours under limited circumstances, for a variety of reasons (especially the difficulties in keeping track of volunteer hours and in assigning a fair market value to them), most volunteer contributions still go unreported in financial statements or, at best, are included as a footnote (Canadian Institute for Chartered Accountants 1980; Cornell Cooperative Extension 1995). Where volunteer labour is noted, it is in the Summary of Significant Accounting Policies included in the notes to the audited financial statement reports. For example, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) includes this note in its financial statement: “AARP and its members benefit from the efforts of many volunteers. These in-kind contributions by volunteers are not recorded in the consolidated financial statements as they do not meet the requirements for recognition under generally accepted accounting principles” (AARP 2000, 9).

Two Models

Accounting statements miss a critical aspect of the operation of nonprofits—that of their volunteer contributions—even though, as has been demonstrated through numerous national and international surveys, these contributions are significant. The following two models include these contributions as part of their reporting, and integrate the financial with the social to tell a different story than would be told by traditional accounting alone.

a) Community Social Return on Investment Model

In a study of a nonprofit called the Computer Training Centre, Richmond (1999) included an estimate for volunteer contributions within a model for assessing a nonprofit’s impact using the Community Social Return on Investment model, presented in detail in Quarter, Mook, and Richmond (2003). Computer Training Centre provided training for people on social assistance because of various forms of disability in an effort to enhance the probability of the participants finding gainful employment. Although the Centre had a paid staff, their contribution was augmented by an active cadre of volunteers who were members of the board and the business advisory committee. These volunteers also assisted with interview preparation and job guidance, obtaining placements and jobs for clients, and in developing and evaluating curricula to reflect the needs of the job market.

The Community Social Return on Investment model included volunteers both as an incoming and outgoing resource. The technique for establishing a comparative market value for volunteers was as follows: Prior research with nonprofits used an average social service wage of $12 per hour to estimate the value of volunteer contributions (Ross and Shillington 1990), however, this estimate appeared low in the case of the Computer Training Centre volunteers, who applied their extensive private-sector management skills and contacts to augment the program. Therefore, a method was developed that attempted more accurately to reflect the value of the volunteer contribution for the 1994-1995 fiscal year. As is the case with many nonprofits, the organization did not track the hours spent by its volunteers so estimates were needed. The executive director of the organization estimated that 10 volunteers on the business advisory committee and eight board volunteers spent 2,896 hours serving on five committees: placement (614 hours); evaluation (216 hours); job guidance (1,600 hours); curriculum review (18 hours), and board of directors (448 hours). These estimates were corroborated in interviews with board volunteers. The executive director was asked his opinion about which was closer to the value of the volunteers’ contribution —their professional work or equivalent skill and effort to his own position. He estimated the board members’ average yearly salary to be $72,500, or $37.18 per hour (based on a standard measure of 1,950 hours of work in a year).

The executive director then estimated the percentage of executive skill capacity that volunteers employed to complete their tasks with the Centre—20 per cent of their professional capacity for each of the committees (for 2,448 hours) and 35 per cent of their professional capacity for the board of directors (for 448 hours). Using these figures, the value of the committee work was calculated at $37.18 X 2,448 hours = $9,106 X 20% = $18,203. For the board of directors, the value was calculated at $37.18 X 448 = $16,656 X 35% = $5,830. Using the executive director’s estimates, the total value of the volunteer contribution was $24,003.

These estimates by the executive director used a combination of opportunity costs (how much the volunteer received for an hour’s work in the workforce) and replacement costs (assessment of what the task was worth to the organization). However, these estimates appeared low for four reasons:

• the researcher’s prior experience with volunteers in similar capacities;

• observation of some of the Centre’s volunteers applying their skills;

• descriptions of the Computer Training Centre’s volunteer tasks; and

• volunteers’ descriptions of their activities.

Because of the discrepancy between these points of views, the value of the volunteer contribution was assessed as the average of the following:

a) an estimate based on the assumption that the members of the board of directors and committees were using their full professional skills in their volunteer activities at the Computer Training Centre, and

b) the executive director’s estimate that the members of the board of directors and committees were using only 35 per cent and 20 per cent respectively of their professional skills in their volunteer activities at the Computer Training Centre.

For the first estimate, working at 100 per cent of professional capacity, the value of these activities was calculated at 2,896 hours X $37.18 per hour X 100%, or $107,673. For the second estimate, working at a reduced level of professional skill, the calculations were: 2,448 hours X $37.18 per hour X 20%, or $18,204; plus 448 hours X $37.18 per hour X 35%, or $5,830. Therefore, for the second estimate, the total was $24,033 ($18,204 plus $5,830). The average of these two estimates becomes $107,673 plus $24,033 divided by 2, or $65,853. This amount was entered into the report as both an incoming and outgoing source.

The reason for treating volunteer contributions both as an incoming and outgoing resource is that, like revenues, they represent a contribution from the community that permitted the agency to provide its services but, like expenditures, this contribution was returned to the community. Arguably, the value of volunteers that was returned to the community was enhanced as a result of the experience with the agency. Volunteers develop skills through their volunteering experience that should be treated as value added, however there are also costs associated with volunteer management. For the purposes of this model, it was assumed that volunteer contributions that remained with the Computer Training Centre at the end of the fiscal year offset the costs. Therefore, the Community Social Return on Investment statement, the value of the volunteers as incoming and outgoing resources, was the same.

b) Expanded Value Added Statement

The Expanded Value Added Statement treats the valuation of volunteers in a slightly different manner. Unlike the Community Social Return on Investment model, it uses a replacement cost framework only and targets the comparative market value to the particular type of organization.

Value added is a measure of wealth that an organization creates by “adding value” to raw materials, products and services through the use of labor and capital; it can be thought of as revenues less purchases of external goods and services. Value added looks beyond the wealth (profit) created for shareholders and includes the wealth for a wider group of stakeholders such as employees, creditors, government and the organization itself. Unlike a Community Social Return on Investment model, a Value Added Statement is recognized by accounting regulatory bodies. That said, it is not widely used in Canada and the United States although common in Western Europe and South Africa.

The traditional Value Added Statement relies upon audited financial statements for its information. By comparison, the Expanded Value Added Statement includes social inputs based on appropriate market comparisons, and this procedure is applied to volunteer contributions. The Expanded Value Added Statement was originally created by Mook and applied by Richmond and Mook (2001) to a university residence complex that is run by students as a co-operative. It was subsequently applied to a group of nonprofits as part of the International Year of the Volunteer Project. The procedure discussed in this article is based on one of the nonprofits in that project, the Ontario Chapter of the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation.

The Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation is the largest charitable organization in Canada dedicated exclusively to the support and advancement of breast cancer research, education, diagnosis, and treatment. The Breast Cancer Foundation is an example of a voluntary organization in that it is funded almost entirely through fundraising from donors and its volunteers heavily outnumber the paid staff.

The Foundation was established in 1986 by a group of eight community leaders and, since its inception, it has awarded grants and fellowships totalling millions of dollars to breast cancer research and educational initiatives in Canada. In order to achieve its goals, it raises funds in many ways, including several high-profile fundraising events such as its annual Run for the Cure and its Awareness Days. The first Run took place in 1992 with 1,500 participants and raised $83,000. It has since grown to be Canada’s largest single-day fundraising event, with more than 140,000 participants in 34 cities.

In addition to funding research initiatives, the Breast Cancer Foundation funds many community-based breast cancer projects and programs through its chapters and branches across Canada. The Ontario Chapter also provides Research and Advanced Fellowship Awards for physicians and healthcare professionals in related disciplines.

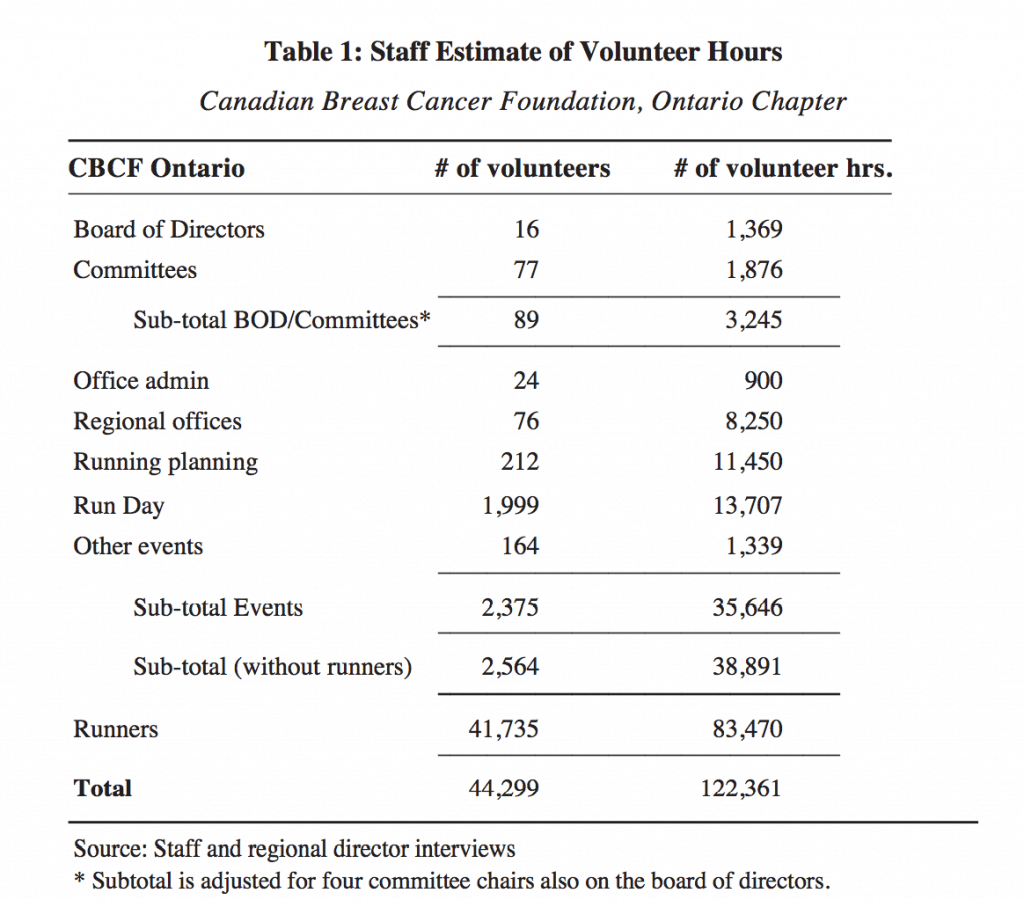

For the fiscal year ending March 31, 2001, staff estimated that the Ontario Chapter was assisted by 2,564 core volunteers. These served on regional committees and boards, standing committees that reported to the board (such as grant review committees), as well as in planning and organizing special events. In total, they contributed 38,891 hours. In addition, an estimated 41,000 runners participated in the Run for the Cure in Ontario, contributing over 83,000 hours to this event. Including Run Day participants, a total of 44,303 volunteers contributed an estimated 122,361 hours to the Breast Cancer Foundation, Ontario.

Table 1 shows the estimates of volunteer numbers and hours by role.

Table 1: Staff Estimate of Volunteer Hours

Based on this estimate, volunteer activities accounted for 84 per cent of the Ontario Chapter’s human resources and contributed 67 full-time equivalent (FTD) positions for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2001. Thus the Breast Cancer Foundation, Ontario, had the equivalent of a total workforce FTE of 80, not just the paid staff FTE of 13. Furthermore, when considering the financial and in-kind resources of the organization, volunteer hours and nonreimbursed out-of-pocket expenses together accounted for 30 per cent of the total.

Based on this estimate, volunteer activities accounted for 84 per cent of the Ontario Chapter’s human resources and contributed 67 full-time equivalent (FTD) positions for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2001. Thus the Breast Cancer Foundation, Ontario, had the equivalent of a total workforce FTE of 80, not just the paid staff FTE of 13. Furthermore, when considering the financial and in-kind resources of the organization, volunteer hours and nonreimbursed out-of-pocket expenses together accounted for 30 per cent of the total.

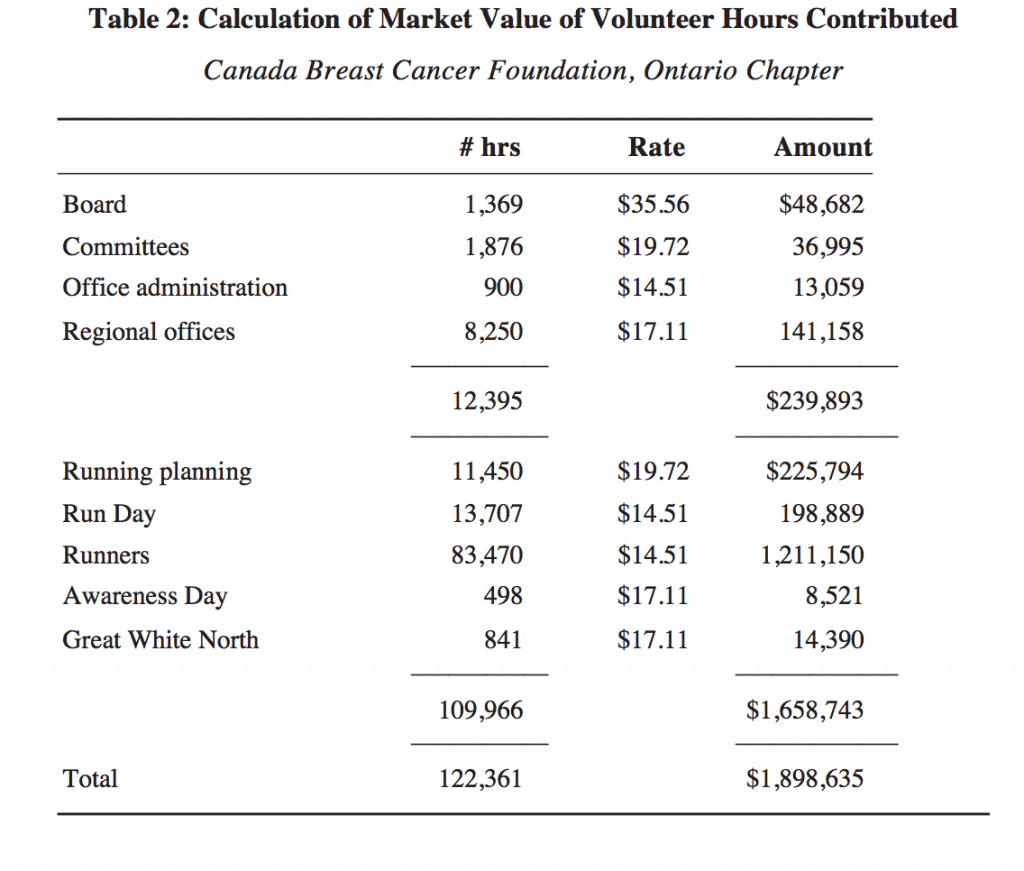

The comparative market rates used in this study were obtained from Statistics Canada, which provides hourly wage rates organized according to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). This classification system (jointly developed by the statistics agencies of Canada, the United States and Mexico) classifies organizations such as businesses, government institutions, unions, and charitable and nonprofit organizations according to economic activity.

For the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation, volunteer hours contributed were valued primarily according to NAICS subsector 813 “grant-making, civic professional and similar organizations”. This subsector includes organizations engaged primarily in awarding grants from trust funds, or in soliciting contributions on behalf of others, to support a wide range of health, educational, scientific, cultural and other social welfare activities. For the year end March 31, 2001, the wage rate for hourly paid employees in this category for Ontario was $14.51. For salaried employees it was $19.72, and the midpoint of the two rates was $17.11. Committee members and Run Day planning organizers were assigned the $19.72 value, based on salaried employees. Office administration, Run Day volunteers, and runners were allocated a comparative market value of $14.51, based on hourly paid employees. Volunteers in regional office or those assisting with awareness days and other special events were assigned a value of $17.11, based on the average of hourly paid and salaried employees.

Table 2: Calculation of Market Value of Volunteer Hours Contributed

As the NAICS rates do not take into consideration governance tasks such as those performed by the board of directors, a second source of wage rates was chosen for these contributions. For the volunteers who were members of the board of directors, the rate was taken from Human Resources Development Canada (HDRC) Standard Occupational Code 0014, “senior managers of health, education, social and community services and membership organizations”. For the time period studied, the midpoint hourly rate for this category was $35.56 per hour.

The total comparative market value for the hours contributed by core volunteers through specific programs is presented in Table 2. These values were obtained by taking the total hours contributed by volunteers within a program and multiplying them by the appropriate hourly rates. As seen, the estimated market value of these contributions is $1,898,635.

Breast Cancer Foundation volunteers also contributed to the organization by paying for items out of their own pockets and not requesting reimbursement. These included travel, meals, supplies, and parking expenses related to volunteering. The amount of these out-of-pocket expenses was determined from the responses to a survey in which volunteers were asked to indicate whether or not they had been nonreimbursed for out-of-pocket expenses and were then asked to break this amount down into categories on the survey. Based on survey responses, 86 per cent of board and committee members indicated nonreimbursed expenses averaging $402.12 per year, while 83 per cent of office administration and regional office volunteers indicated average expenses of $75. Seventy-seven per cent of the remaining volunteers indicated out-of-pocket expenses averaging $75 for event planners and $12.50 for event-day assistants and participants. The total of all these expenses was $481,112. This amount was analogous to a financial donation by the volunteers to the Foundation.

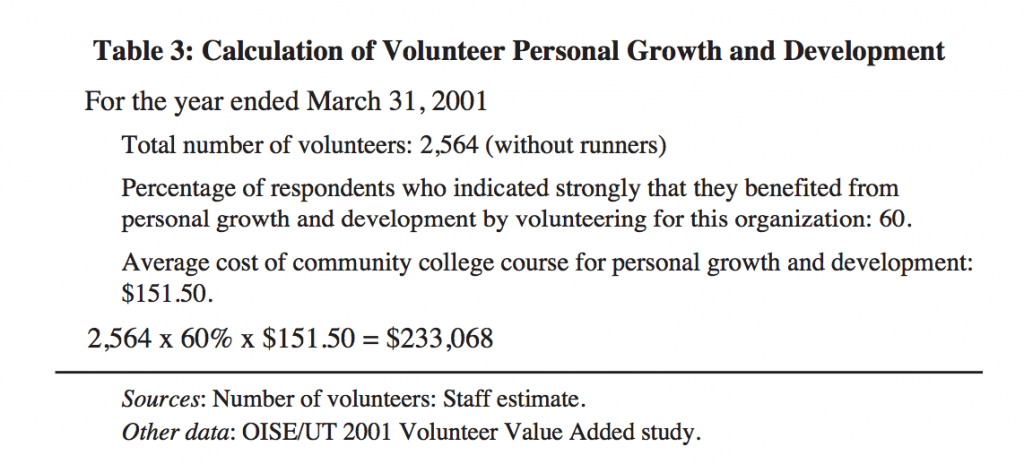

The Breast Cancer Foundation also created value when, as a result of the volunteer experience, volunteers developed skills and experienced personal growth. Our survey of volunteers at the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation included a section on benefits received by volunteers from their volunteering experiences including choices regarding the development of new skills, the strengthening of existing skills, social interaction, improvement in wellbeing, and opportunities to try new things.

At the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation, 60 per cent of survey respondents (excluding runners) indicated that they benefited strongly in terms of personal growth and development by volunteering for the Foundation.

Table 3: Calculation of Volunteer Personal Growth and Development

To calculate the market value of volunteer personal growth and development, the total number of core volunteers (2,564) was multiplied by the 60 per cent of respondents who indicated strongly that they had benefited. The next step was to assign a comparative market value to this benefit. The value selected was the average cost of a community college course for personal growth and development ($151.50). This seemed a conservative estimate of the market value of the volunteers’ personal benefits and resulted in a total value of 2,564 X 60% X $151.50 = $233,068.

The personal growth and development of volunteers was seen as a secondary output within the Expanded Value Added Statement. It was not directly related to the provision of the organization’s services, as were volunteer hours and volunteer out-of-pocket expenses, but rather was an indirect effect of those services.

Discussion

Both of these models indicate how volunteer contributions can be calculated for presentation within a social accounting framework. In the book, What Counts: Social Accounting for Nonprofits and Cooperatives, we also present a Socioeconomic Impact Statement and a Socioeconomic Resource Statement that include volunteer contributions. In all cases, the inclusion of volunteer contributions tells a much different story about an organization than financial information alone.

While these practices may seem controversial within conventional accounting practices, they help to bring out the social impact of nonprofits and therefore fit within a social accounting framework. There are varying definitions of social accounting, but all expand the range of criteria that are taken into consideration when measuring performance and all look at the organization in relation to its surrounding environment, both social and natural. Additionally,

all emphasize that the audience for social accounting is broader and may differ from that for other forms of accounting (Estes, 1976; Gray, Owen, and Adams, 1996; Gray, Owen, and Maunders, 1987; Institute of Social and Ethical Accountability 2001; Mathews and Perera 1995; Ramanathan 1976; Traidcraft 2000).

In general, social accounting has focussed on a critique of the limitations of conventional forms of accounting as applied to profit-oriented businesses which have in large part bypassed nonprofits. Our work attempts to integrate social accounting and nonprofits by demonstrating how financial statements can be broadened to include the social value generated by nonprofits, one component of which is the contributions of their volunteers.

REFERENCES

American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). 2000. Notes to the Financial Statements.

http://www.aarp.org/ar2000/graphics/pdfs/fin_full.pdf (9 June 2002).

Brown, Eleanor. 1999, May. “Assessing the value of volunteer activity”, Nonprofit and

Voluntary Sector Quarterly 29 (1): 3–17.

Brudney, Jeffrey. 1990. Fostering volunteer programs in the public sector. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA). 1980. Financial reporting for non-profit organizations. Toronto: Canada Institute of Chartered Accountants.

Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA). 1996. CICA Handbook, Sections 4400–4460. Toronto: Canada Institute of Chartered Accountants.

Community Literacy of Ontario. 1988. The economic value of volunteers in community literacy agencies in Ontario. Toronto: Author.

Cornell Cooperative Extension. 1995. Financial Operations Resource Manual, code 817. http://www.cce.cornell.edu/admin/fhar/form/code0800/817.html (10 June 2002).

Estes, Ralph. 1976. Corporate social accounting. New York: John Wiley.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 1978. Statement of financial accounting concepts

No. 1 Objectives of financial reporting by business enterprises. Norwalk, Conn.: FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 1993. Statement of financial accounting standards No.116: Accounting for contributions received and contributions made. http://

www.fasb.org/st/summary/stsum116.shtml (5 June 2002).

Gaskin, Katharine. 1999. “Valuing volunteers in Europe: A comparative study of the Voluntary Investment and Value Audit (VIVA)”, Voluntary Action: The Journal of Active Volunteering Research 2 (1): 35–48.

Gaskin, Katharine, and Barbara Dobson. 1997. The economic equation of volunteering. http://www.jrf.org.uk/knowledge/findings/socialpolicy/SP110. asp (24 May 2002).

Gray, Rob, Dave Owen, and K.T. Maunders. 1987. Corporate social reporting: Accounting and accountability. London: Prentice Hall.

Gray, Rob, Dave Owen, and Carol Adams. 1996. Accounting and accountability: Changes and challenges in corporate social and environmental reporting. London: Prentice Hall.

Hall, Michael, Larry McKeown, and Karen Roberts. 2001. Caring Canadians, Involved Canadians: Highlights from the 2000 National Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Handy, Femida, and Hans Srinivasan. 2002. Volunteers in hospitals: Scope and value.

Toronto: York University. Photocopy.

Independent Sector. Independent Sector home page. 20b. http://www.independentsector. org/media/voltimePR.html (22 June 2001).

Independent Sector. 2002. Research home page. Value of volunteer time, http://www.independentsector.org/programs/research/volunteer_time.html (14 May 2002).

Institute of Social and Ethical Accountability (ISEA). 2001. What is social and ethical accounting, auditing and reporting?. London: ISEA. http://www.accountability. org.uk (23 May 2002).

Karn, G. Neil. 1983. “Money talks: A guide to establishing the true dollar value of volunteer time”, Part 1. Journal of Volunteer Administration 1 (Winter): 1–19.

Kendall, Jeremy, and Stephen Almond. 1999. United Kingdom. In Global Civil Society: Dimensions of the nonprofit sector, ed. Lester Salamon et al., 179–200. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mathews, M. Reg, and M.H.B. Perera. 1995. Accounting theory and development. 3d ed.

Melbourne: Thomas Nelson.

Quarter, Jack, Laurie Mook, and Betty Jane Richmond. 2003. What counts: Social accounting for nonprofits and cooperatives. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Ramanathan, Kavasseri. 1976. “Toward a theory of corporate social accounting”, The Accounting Review 51 (3) 516–528.

Richmond, Betty Jane. 1999. Counting on each other: a social audit model to assess the impact of nonprofit organizations. Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto.

Richmond, Betty Jane, and Laurie Mook. 2001. Social audit for Waterloo Cooperative

Residence Incorporated (WCRI). Toronto. Report to WCRI.

Ross, David. 1994. How to estimate the economic contribution of volunteer work. Ottawa: Department of Canadian Heritage.

Ross, David, and Richard Shillington. 1990. Economic dimensions of volunteer work in

Canada. Ottawa: Secretary of State.

Salamon, Lester, Helmut Anheier, Regina List, Stefan Toepler, S. Wojciech Sokolowsky, and Associates. 1999. Global civil society: Dimensions of the nonprofit sector. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sharpe, David. 1994. A portrait of Canada’s charities. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy. Traidcraft. 2000. Traidcraft 1999/2000 social accounts. http://www.traidcraft.co.uk/sa2000

sindex.html (14 May 2002).

Wolfe, Nancy, Burton Weisbrod, and Edward Bird. 1993. “The supply of volunteer labor: The case of hospitals”, Nonprofit Management and Leadership 4 (1): 23–45.