In the previous article “The Tax Treatment of Charities” the basic rules relating to the taxation of charities which apply to 1977 and subsequent taxation years were reviewed. In this article we have assumed that the reader is familiar with the basic rules and have focused on a number of potential problem areas in the legislation.

In their zeal for reform of real and imagined inequities in the charity area the lawmakers have introduced one more sleeping dragon into the tax laws. On an initial perusal, the new rules relating to the taxation of charities might app ar to be straightforward, but a closer review would indicate a fundamental change in the underlying concept of the treatment of charities and a myriad of problems lurking beneath the deep.

It is understood that the draftsmen of the legislation included many of the provisions to enable Revenue Canada to police those charities abusing the system and did not intend to upset the activities of the legitimate charities. Unfortunately, once the provisions were enacted into law they apply to every charity and no charity can assume the rules will not be applied to them. Therefore, although many of the problems raised in this article appear to be academic they do have practical significance and this will become apparent as charities attempt to apply the new rules to their operations.

History

Prior to 1977, most not-for-profit organizations were exempt from tax as charitable organizations, non-profit corporations, charitable trusts, or non-profit organizations under paragraphs 149(1)(f), (g), (h) or (1) of the Income Tax Act (the “Act”) respectively. Not-for-profit organizations, including charities, were not required to register with the Department in order to be exempt from tax. Only those charities which wished to issue tax receipts to donors were required to register and such registered charities were known as “registered Canadian charitable organizations”.

The Department did not actively regulate those organizations that were not registered and did not appear to be overly concerned with the whole not-for-profit area. In most cases there was no particular fiscal advantage to the Government in monitoring such organizations and unless there was obvious abuse, the Department left them alone. In fact, because many trustees and directors did not believe that there were any reporting requirements, the Department frequently had no knowledge of the organization’s existence.1

If a charity was a “registered Canadian charitable organization” as defined in former paragraph 110(8)(c) and its registration was subsequently revoked in the manner described in section 168, the charity could no longer issue receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a). There was no penalty tax and revocation did not necessarily mean that the organization was no longer tax exempt.

Current approach

The recent amendments reflect the apparent intent of the lawmakers to regulate charities to a greater degree. There are a number of significant changes. For example, under the new rules charities must be registered to be exempt from tax, non-profit organizations must be able to satisfy the Minister that they are not charities in order to claim exemption under paragraph 149(1)(l), and there is a “super” penalty tax imposed where the registration of a charity is revoked.

Every charity must be registered to be tax-exempt

Under the new rules only a “registered” charity is exempt from tax under Part I of the Act.2 This change means that a charity must have registered status in order to issue receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a) and to be exempt from tax. An organization that was a “registered Canadian charitable organization” under the old system on December 31, 1976 will be deemed to be a “registered charity” for the purposes of the new system.3 Therefore, these charities do not have to register. A charity that was not registered under the old system and new charities will have to register. This procedure is outlined in Appendix A.

To Register or Not to Register

There are a number of significant advantages in registering a charity with the Department. Its income is exempt from tax, tax receipts can be issued for donations and the charity appears, in the eyes of the public, to have the Department’s “stamp of approval”. However, there is a cost. The charity’s affairs are open to public scrutiny and the charity must meet reporting requirements, minimum disbursement requirements and other restrictions. There is a loss of full control of the assets and a potential “super” penalty tax.

The charity should carefully consider the advantages and disadvantages to determine if it should register. The charity must not only determine if it could qualify for registration today, but also if it can meet the requirements in the future (e.g. terms of will, trust agreement, wind-up). Normally major considerations arc the need to issue tax receipts and whether income should be exempt from tax. It may be that the charity would have no income in which case it may not be necessary to register. For example, a charitable trust may have no income subject to tax after the allocation to charitable beneficiaries or such a small income that no tax would, in fact, be exigible. By virtue of subsections 104(6) and 104( 12), income of a trust which is allocated to a beneficiary or which is included in computing the income of a beneficiary may be deducted in computing the income of the trust.4

Sub-Units

In some cases the main body of a charity may be registered while its sub-units may not. The definition of “registered charity” in paragraph 110(8)(c) allows branches, sections, etc. of the main body that do not receive donations on their own behalf to operate under the main body’s registration. However, if the sub-units usc the main body’s registration number, any receipts issued by them must be in the name of the main body and the main body will be required to report all financial activities of the sub-units in its returns. Futher, the sub-units will be required to be under the control of the main body. If the sub-units act autonomously, they must be registered separately.

Where the sub-units arc presently registered it should be possible, depending on the particular circumstances, to rearrange their affairs so that they operate as one registered charity. This would require the sub-units to request revocation of their registrations and to transfer all of their assets to the parent charity (or vice versa). In that event only one registered charity would remain. One problem in consolidating the sub-units in this manner is that the parent will become responsible for all the actions of the sub-units. In a small sub-unit staffed by volunteers, this may not be desirable as its books and records may be less than adequate and control over the issue of tax receipts may be weak. This could result in revocation of its registration and the imposition of the penalty tax. In such circumstances the parent may prefer not to assume responsibility for the sub-unit and endanger its own registration. Assuming the sub-unit remains separate and if revocation did occur and it became necessary for the sub-unit to transfer its assets to another charity, it should be possible to transfer the assets of the sub-unit to the parent at that time.

It might be noted that frequently too many divisions or sections of one charity register separately. The result is often the creation of additional reporting requirements and problems which otherwise would not exist. For example, where there is one registered charity the results can be averaged in the year. If one sub-unit spends more than is required and another spends less, averaging will be beneficial. If the two sub-units arc separately registered, such averaging is not permitted.

The Paragraph 149(1)(l) Problem

The definition of a non-profit organization in paragraph 149(1)(l) was amended by adding the requirement that the organization “in the opinion of the Minister, was not a charity within the meaning assigned by subsection 149.1(1)”. If an organization can persuade the Minister that it is not a charity within the meaning assigned by subsection 149.1(1) and otherwise comes within the definition of a non-profit organization set forth in paragraph 149(1)(l), its income will be exempt from tax. The objects of organizations referred to in paragraph 149(1)(l) are usually not charitable, but it may happen that the objects of such an organization are very similar to the objects of a charitable organization.

If an organization should have some of the characteristics of a charitable organization or foundation but should consider itself not charitable and claim exemption from income tax under paragraph 149(1)(l) and if the Minister should at some time determine that the organization was a charity, it appears that the Minister could assess the organization on the basis that it was a charity which was not registered and was therefore subject to tax on its income. If no assessment had been issued in respect of a particular taxation year, it appears that the four year limitation would not apply and the Minister could assess the organization at any time on the basis that it was a charity which was not registered.

If there appears to be any possibility that a non-profit organization may be a charity, we would suggest that the organization write to the Department at the address given in Appendix A for confirmation that the organization is not a charity. It would probably be necessary to provide the Department with complete information to allow a proper determination. This would include information such as a description of its activities, objects, articles, by-laws, trust documents, financial statements, etc. The disadvantage in drawing the organization to the Department’s attention is that this information may be sent by the Department to the organization’s local District Office for scrutiny. If the information is forwarded to the District Office it will review the information to determine if the organization should be tax-exempt as a non-profit organization within the meaning of paragraph 149(1)(l) and if its investment income will be subject to tax under subsection 149(5). 5

Reference to the Minister

Throughout the provisions in the Act relating to charities the Minister is given considerable discretionary power. Notwithstanding the reference to the “Minister” throughout the provisions, Regulation 900 permits the Director, Registration Division of the Department of National Revenue, Taxation to exercise the powers and perform the duties of the Minister under section 149.1, subsections 168(1) and (2) paragraphs 110(8)(c) and 149(1)(l). The Chief, Charitable and Non-Profit Organizations Section of the Department of National Revenue, Taxation may exercise the powers and perform the duties of the Minister under subsections 149.1(7), (8), (13), (15) and (20), 168(1) and paragraphs 110(S)(c) and 149(1)(l). For a complete listing sec Regulations 900(7) and 900(8).

It would appear that an opinion from either the Director or the Chid would be sufficient if an organization wished to clarify its status with respect to paragraph 149(1)(I). The address is given in Appendix A.

Categories of Charities

Under the new rules a charity will be categorized as a charitable organization, a public charitable foundation or a private charitable foundation. There is no public-private distinction for the charitable organization. Normally, the requirements of the charitable organization will be the least restrictive and the requirements of the private charitable foundation the most restrictive and it is normally most advantageous to be a charitable organization or, if it is necessary to be a foundation, a public foundation. This may not always be the case, however, and particular circumstances will have to be considered. For example, a public charitable foundation can exclude “10-year gifts” from receipted income and income, a private foundation does not have a receipted income test as such, and a charitable organization does not have a 90% of current year’s income test.

It may be possible to arrange the affairs of a charity so that it moves from one category to another. In this regard consider the 50% of income test in paragraph 149.1(6)(b), the associated designation provision (subsection 149.1(7) and paragraph 149.1 (6)(c)) and the designation of a private foundation as public (subsection 149.1 (13)).50o/l! of Income Test

It would appear from reading the revised T2052 that the Department will consider a charity to be a charitable organization unless it expends in excess of 50% of its income by way of gifts to qualified donees (excluding approved associated charities). This seems to tie into paragraph 149.1(6)(b) in that a charitable organization shall be considered to be devoting its resources to charitable activities carried on by it to the extent that in any taxation year, it disburses not more than 50% of its income for that year to qualified donees. A question arises as to whether it is desirable to categorize a charity annually on such an arbitrary basis, particularly as it appears to be possible for a charity to choose the category into which it falls by manipulating the use of its income. For example, if a charity wishes to ensure it will be categorized as a charitable organization for tax purposes, it could reduce its giving to qualified donees, subject to meeting the test that it was devoting all of its resources to charitable activities carried on by the organization itself.

It may happen that the charity does not know if the donees are qualified donees or not. Further, many charities will not know what 50% of the income for the year will be at the time of the gift and as a result may inadvertently exceed 50%.

It appears to us that the possibility of a charity changing its category for tax purposes from year to year depending upon its use of its income and how much is given to qualified donees is not workable and we would not be surprised if the Department eventually goes back to a more traditional distinction. Perhaps the charity should anticipate this change in policy and look to the traditional meanings of foundation and charitable organization, decide which applies to it and then act accordingly.

Association

Where two or more registered charities have substantially the same charitable aim or activity it may be possible, by applying to the Minister in prescribed form (Form T3011), to have the charities deemed to be associated.7 This can be significant as paragraph 149.1(6)(c) provides that a charitable organization shall be considered to be devoting its resources to charitable activities carried on by it to the extent that it disburses income to a registered charity that the Minister has designated in writing as a charity associated with it. That is, up to 100% of its income could be transferred to an associated charity and the 50% of income test would not take those amounts into account. This facilitates the transfer of funds between such related charities.

Association should be seriously considered whenever registered charities have the same aim or activity. For example, a private school and its foundation, a national charity and its provincial bodies, a diocese and its individual parishes. In the case of a private school and its foundation, if the foundation is not associated with the school and it gives more than 50% of its income to the school it will be considered a foundation. However, if it is associated with the school it appears it could give I00% of its income to the school and be considered a charitable organization. As mentioned above, the circumstances in each specific case must be reviewed to determine the best category. In our example, the foundation would have to weigh the advantage of not having to. meet a 90% of current income test with the disadvantage of not being able to exclude “10-year gifts” in computing the disbursement requirements.s It should be possible to have the associated designation back-dated as subsection I 49.1(7) refers to a “date specified”.

An interesting question arises where two or more charities are associated and one wishes to terminate its associated designation as to whether it has any right to do so. It appears from the provision that only the Minister may revoke the designation and that the charity would have no right to terminate.

Designation of Private Foundation as Public

The requirements of private foundations differ significantly from those of public foundations and certain private foundations may find it less restrictive if they could operate under the public foundation requirements.

In the discussion paper, The Tax Treatment of Charities, tabled with the June 23, 1975 budget the following comments were made:

“The Minister of Revenue Canada would have the discretion to designate a charity which is, under these rules, a private foundation, to be a public foundation if he is satisfied that in any specific situation the facts warrant such a designation. Thus the Minister might decide that a foundation which received all its initial funding from one person should be treated as a public foundation when additional funds are received from other sources who arc at arm’s length from the initial donor.”

This particular proposal is reflected in subsection 149.1(13) of the Act which provides that on application made to him by a private foundation, the Minister may, on such terms and conditions as he considers appropriate, designate the foundation to be a public foundation, and on and after the date specified in such a designation, the foundation to which it relates shall, until such time, if any, as the Minister revokes the designation, be deemed to be a public foundation.

There is no prescribed form for requesting this designation and application is made by letter.

The intent in subsection 149.1(13) appears to be to provide a means to correct a situation where a foundation accidentally becomes a private foundation in a technical sense. For example, a foundation may find that it is unable to meet one or both of the requirements in paragraph 149.1(1)(g) even though its overall characteristics are such that it should be public. The wording in subsection 149.1 (13) allows the Department to review each case separately and to decide on the facts in the specific situation if the charity should be public. If the decision is to refuse the designation as a public foundation, the foundation does not have a formal right to appeal.

Although no guidelines have been issued on subsection 149.1(13) at the time of writing, it is unlikely that public designation would be given where a foundation is clearly a private foundation as, for example, a foundation established and controlled by one individual. It might be given where, for example, a hospital sets up its own research foundation or a small public foundation receives a large contribution from one person which exceeds 75% of capital contributed to date.

Income of a Charity

Ceneral Background

The determination of the income of a charity raises a number of conceptual problems. This is due in part to the fact that charities do not have a profit purpose. Their objective is to provide the best possible service given the resources of the charity.

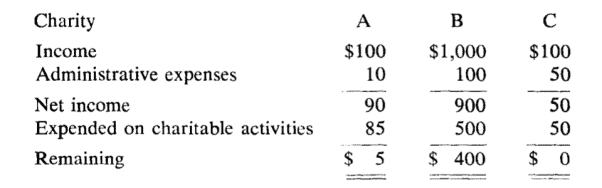

A charity incurs many of the same expenses as a profit-making entity but unlike the profit making entity a charity also expends amounts on charitable activities or gifts to qualified donees. Certain expenses may be deducted in computing the “net income” of the charity and this “net income” is the amount available to fund the cost of the charitable activities and of providing the services. The amount remaining after deducting the charitable activity and service costs would reflect how much was available but was not used in the provision of services. The prime objective is to provide a service. The size of the net income of the charity is not as important as the actual use of that income. For example, consider the following charities:

The result in B might be quite commendable if B were a profit making entity. That is, it has the highest income and net income and it has managed to retain a significant amount of this income. It has a “good profit”. If B is a charity, however, it is obvious B did not do very well. It had $900 available for services but it only used $500. It failed to meet its prime objective of providing the best possible service given its resources. C, on the other hand, spent everything it received. Its income was $100 and its expenditures were $100. However C’s administrative expenses were 50% of income and it seems fairly clear that C did not do everything possible to maximize the resources available for services. A, then, seems to have done the best job and the fact that $5 remained is not important. It is impossible for any charity to always break even. The fact that it does not have a profit motive does not mean it should not have a profit. Every charity needs a minimum capital base and there is nothing objectionable in reserving small portions of the net income to add to the base.

The amendments to the Act try to encourage the A situation and prevent B and C situations. For example, one part of the disbursement requirements of a charitable foundation requires the foundation to expend at least 90% of income for the year. This is 90% of net income. In our example, this would be 90% of $90, 90% of $900 and 90% of $50. A and C met this test. B did not and the requirement in the Act forces B to increase its expenditures on charitable activities. We think most people would agree this is reasonable and justified. What provisions are there in the Act to force C to reduce its administrative expenses? There is a general provision in section 67 which provides:

“In computing income, no deduction shall be made in respect of an outlay or expense in respect of which any amount is otherwise deductible under this Act, except to the extent that the outlay or expense was reasonable in the circumstances”.

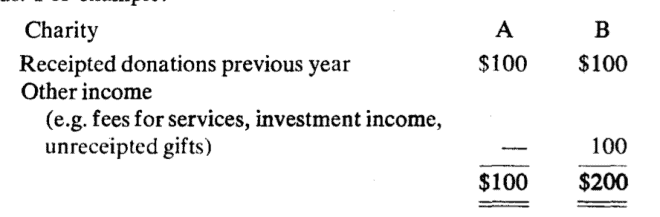

This provision could be used to prevent a charity from deducting excessive amounts on account of salaries, rent, etc. In addition, there is a requirement that 80% of receipted donations of the previous year be expended on charitable activities or gifts to qualified donees. If we assume that all of the income of A, Band C in the previous year consisted of receipted donations of $100, $1,000 and $100 respectively, the requirement in the current year would be 80% of $100, 80% of $1,000 and 80% of $100. C did not meet this test. This test was designed to limit fund raising and administration costs, but few charities receive 100% of income in the form of receipted donations so in practice the test is not that onerous. For example:

A and B would have to expend on charitable activities at least $80 (80% x $1 00). A would be left with $20 for other expenses such as administration and fund-raising. B would be left with $120. If B were a public charitable foundation it would also have to consider the 90% of current income test but if B were a charitable organization its only specific disbursement requirement would be $80.

A question arises where a charity wishes to accumulate the income which it is not required to spend as to whether, when it accumulates such income, it is devoting all its resources to charitable activities as required. This question does not app ar

so long as the accumulations are not excessive there would be no problem. Many provisions of the Act contemplate that some assets of the charity will be retained. Therefore, it seems reasonable that charities be permitted to accumulate monies remaining after required disbursements have been made in any particular period purposes at some time. If abuses develop, a court might find there was a breach of obligation and require distribution of the excess assets.

Another question that may arise is whether the gross income of the charity is what it should be. This problem will mainly arise in private foundations. For example, a private foundation set up by the major shareholder of a private family corporation might be used to finance the corporation by low interest loans. The Act tries to prevent this by introducing a requirement that an amount equal to at least 5% of the fair market value of certain capital properties of a private foundation be expended for charitable purposes. As a result, the minimum return allowed on these types of investment would be 5%. It should be noted that the test is based on fair market value. An investment receiving, for example, a 2% return may not have a fair market value equal to the principal amount. If the principal amount were paid by the charity, it might be considered to have conferred a benefit on a member, shareholder, trustee, settlor, etc. and by definition the foundation might no longer be a charitable foundation.

This type of abuse is less likely to occur in the case of charitable organizations and public foundations as most transactions by such organizations would beat arm’s length. Further, the directors and trustees of such organizations are more likely to be accountable to the public for their actions which should deter them from engaging in transactions from which they would derive personal benefit.

As mentioned above, there are specific provisions in the Act to ensure minimum disbursements and prevent various abuses, and we believe most people welcome these provisions. However, numerous problems will arise in trying to fit a charity’s receipts, disbursements and activities into the following format which seems to be necessary if the rules are to be applied as they now read.

Charity A

|

Gross income |

$100 |

|

Administrative expenses |

10 |

|

Net income |

90 |

|

Expended on services |

85 |

|

Remaining |

5 |

Gross Income

The first problem is to determine what is to be included in gross income. The general rule seems to be that income will be calculated under the general provisions of the Act in the same manner as any taxable entity. In addition, for the purposes of section 149.1 there are a number of special rules which must be considered in determining the gross income of a charity.

The general provisions of the Act would bring into income most business and property income. For example, fees for services, investment income including interest and dividends, rent, income from any businesses etc. would generally all be included in income. As noted the special rules in section 149.1 then apply only for the purposes of section 149.1.

It might be noted at this time that a dividend received from a taxable Canadian corporation by a trust that is a registered charity need not be grossed-up9 as no off-setting credit is available to the registered charity.

Capital gains and losses

Subsection 149.1(11) specifically excludes capital gains and losses in “computing the part, if any, of the aggregate of any amounts that is not less than a percentage specified in any subsection of this section of any income for a period”. One has to read this very carefully. Capital gains and losses are excluded only where not less than a percentage of income is specified. For example, subsection 149.1(11) applies to paragraph 149.1(3)(b) and paragraph 149.1(4)(b) but does not appear to apply to paragraph 149.1(6)(b). This seems to be a drafting error. For the purposes of determining whether not less than 90% of income has been expended, income would not include capital gains and losses. However, in determining if not more than 50% of income has been disbursed to qualified donees, it would appear that one-half of net capital gains realized would be included in income.

Donations and gifts

Subsection 149.1(12) requires that all gifts received by the charity in the year, including gifts from any other charity, be included in income. However, there are certain exceptions and these should be carefully noted as, if the gift does not have to be included in income, it will not have to be disbursed as part of the 90% of income test. This can be useful where it is necessary to accumulate capital. These exceptions10 are:

1 . Any gift received subject to a trust or direction to the effect that the property given, or property substituted therefor, is to be held by the charity for a period of not less than 10 years.

2. Any gift or portion of a gift in respect of which it is established that the donor is not a charity and

(a) has not been allowed a deduction under paragraph 110(1)(a) in computing his taxable income, or

(b) was not taxable under section 2 for the taxation year in which the gift was made.

3. Any gift or portion of a gift in respect of which it is established that the donor is a charity and that the gift was not made out of the income of the donor.

“10-year gifts”

The first exception requires that there be a trust or direction to the effect that the property given be held for a period of not less than 10 years. Where a charity receives such gifts it should ensure that there is evidence to this effect. The donor should be asked to stipulate this in writing, if he has not already done so, and such document should be retained by the charity.11

It is important to note that “10-year gifts” are excluded from the income of a charity for the purposes of section 149.112 and that they are also excluded from the receipted donation portion of the disbursement test for a public charitable foundation. 13 However, “10-year gifts” are not excluded in the receipted donation test where the charity is a charitable organization.14 Furthermore, the averaging provision in subsection 149.1(5) refers to “the relevant percentages of those amounts for which it issued receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a) …”No distinction is made between the charitable organization and public charitable foundation. It is therefore not clear in the case of the public charitable foundation that “10-year gifts” would be excluded in determining these amounts for the purposes of averaging.

Donor has not been allowed a deduction under paragraph 110( 1 )(a)

Many charities automatically issue receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a) for all donations received but this may not always be necessary or desirable. Where the donor does not intend to use the full amount of the donation as a deduction under paragraph 110(1)(a), it may be more advantageous to the charity if a tax receipt is not issued for the full amount. For example, where an amount is received by a charity from an estate, the estate may only be entitled to claim a deduction for a small portion of the total payment. Normally, unless there is evidence to the contrary, the Department will assume that, where the charity has issued a tax receipt for the full amount, the donor has been allowed a deduction for the full amount under paragraph 110(1)(a). In addition, the receipted donation tests refer to “amounts for which it issued receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a)”,15 so that the mere issue of the receipt causes the amount for which it was issued to be included for the purpose of these tests.

Income does not include any gift or portion of a gift in respect of which it is established that the donor is not a charity and “has not been allowed a deduction under paragraph 110(1)(a) in computing his taxable income”.16 This may be difficult to prove if a tax receipt has been issued. In order to reduce the amount that has to be distributed pursuant to the income test or receipted donation test, the charity might consider issuing a tax receipt only where it is requested by the donor. Where a tax receipt is not necessary, a letter or other receipt (non-tax receipt) could be used in acknowledgement.

Amounts received from a trust

It is important to realize that the above-noted exceptions apply only where the property is received as a gift. Property received from an estate or trust may not be received as a gift and in such a case the exceptions will not apply. For example, a charity may receive property from an estate or trust under one or more of the following circumstances:

1. As a charitable donation made by the trust and deducted by the trust from its income under paragraph 110(1)(a) in computing its taxable income.

In this case, the amount would clearly be a gift and would be included in income under paragraph 149.1(12)(b) as a gift but would be subject to the exceptions in that paragraph.

2. As an amount allocated to a charitable beneficiary and deducted in computing income by the trust under subsections 104(6) and 104(12).

There would appear to be two provisions in the Act which might bring such amount into the income of the charity. These are subsections 104(13) (or subsection 105(1)) and 149.1(12). Subsection 149.1(12) would only apply if the amount is considered a “gift”. If subsection 149.1(12) does apply, the exceptions in subparagraphs 149.1(12)(b)(i) and (ii) would apply. If the amount is not a “gift” subsection 104(13) or subsection 105(1) would seem to apply and the exceptions in subparagraphs 149.1(12)(b)(i) and (ii) would not apply. The better view appears to be that an amount payable under the terms of a trust to a charitable beneficiary is not a voluntary payment by the trust. It is therefore not a “gift” and the provisions of paragraph 149.1(12)(b) do not apply.

3. As a distribution or payment of capital by the trust.

A bequest under the terms of a will which is payable on the death of the testator is generally considered to be a gift. As a result, where a bequest is made under a will to a charity the amount received by the charity will be a “gift” in its hands which must be included in computing its income pursuant to subsection 149.1(12). In this case the exceptions in subparagraphs 149.1(12) (b) (i) and

(ii) would appiy and the charity should ensure that it does not issue a receipt described in paragraph 0(1) (a) for that amount.

On the other hand, a distribution or payment of capital by an on-going trust to a charitable beneficiary would not normally ba “gift” to the charity but rather the distribution of a capital interest in the trust. Because it would be a capital receipt it would not be included in income.

Allocations of Income by a Trust

It should be noted that subsection 149.1(12) clearly applies only for the purposes of section 149.1. Paragraph 149.1(12)(c) has no relevance in computing the income of a charitable trust under Division B of Part I of the Act. Therefore, if a charitable foundation is a trust subsections 104(6) and (12) are applicable in computing income under Division B although they are not applicable in computing income for the purposes of section 149.1.

Government grants

Many charities receive federal or provincial grants and although most of these charities are charitable organizations an organization can technically be a foundation (e.g. a charity which gives more than 50% of its income to other registered charities not associated with it). In such a situation the question arises as to whether “income” would include government grants.

Normally grants are received as income or to reduce specific expenses of the charity and are added to income or deducted from the expenses following the Department’s policy set forth in Interpretation Bulletin IT-273. The specific expenses of a charity are usually “charitable activity outlays”.17 Applying the reasoning in IT-273, if the grant is to augment income, it would be included in income (unusual for a charity) and if the grant is to reduce specific expenses, it would be deducted from the charitable activity outlays.

There is an argument that the grant should be excluded from income. Pursuant to subparagraph 149.1(12)(b)(ii), a gift can be excluded from income if the donor is not a charity and has not been allowed a deduction under paragraph 110(l)(a) or is not taxable under section 2. If a particular government grant is a “gift” it appears that it can be excluded from income because the government is not a charity. However, in many cases it will be difficult to determine if the grant is in fact a “gift”.

Even if the grant could be excluded from income, it is unlikely that abuses would develop and, if they did, they would be short-lived. Most government grants are related to specific needs and require financial information supporting the application. Therefore, a charity might not distribute the grant in one year, but the next year it is unlikely that it would receive another grant if funds had been retained in the previous year. Other grants may have to be returned if the funds were not used for the specific purpose for which they were given or if any excess remained.

In addition, grants normally only go to active charities (i.e. charitable organizations) and not foundations. Thus, the 90% of income test is not relevant. If a charity was a foundation, received a grant, and did not use it in its disbursement requirements, it would be in the same position as a charitable organization. To receive the grant, it must have had characteristics similar to those of a charitable organization.

A problem might arise with respect to subsection 149.1(6) in that giving in excess of 50% of income to other qualified donees will result in the charity being considered a foundation. If income does not include government grants, 50% of income could be a smaller amount than expected.

Consideration must also be given to “income” as used in the reserve systems (subsections 149.1(18) and (19)). Removing the grant from income could reduce the allowable reserve (maximum is previous year’s income). However, the 90% calculation would be based on income also without including the current year’s grant and therefore that should not be a problem.

As discussed below under the heading “Carry forward” a charitable foundation may carry forward an amount expended in excess of its total income for the year. If subparagraph 149.1(12)(b)(ii) does exclude government grants from the income of charity, a situation may arise where a charitable foundation receives a large grant which it disburses in the year creating a “disbursement excess”.18 In order for this disbursement excess to be eligible for the carry forward provisions described in subsection 149.1(20), prior approval would have to be obtained from the Minister. It seems unlikely that the Minister would approve a carry forward in this type of situation as the exclusion of the grant from income is purely technical and the excess is artificial.

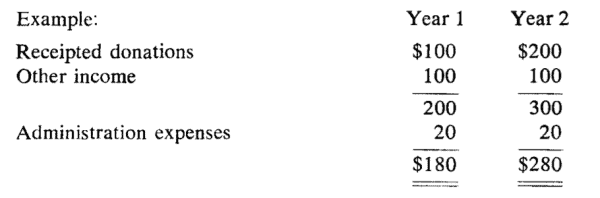

Recipted Income vs. Income

The distinction between receipted income and income is important. Receipted income refers to the aggregate of amounts for which the charity issued receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a). This is a gross amount. The disbursement test of a charitable organization is based solely on this amount. The disbursement test of a public charitable foundation may be based on this amount if it is greater than the amount determined using current year’s income. A public charitable foundation can exclude “10-year gifts” from receipted income19 as well as from income.

It should also be noted that the receipted income total is relevant for the subsequent year’s disbursement test:

Example: Year 1 Year 2

Receipted donations $100 $200

Other income 100 100

200 300

Administration expenses 20 20

— -$180 $280

-In Year 2, receipted income is $200 and income is $280. The disbursement requirement in Year 2 for a charitable organization would be 80% of the previous year’s receipted income or 80% of $100 ($80). The disbursement requirement of a public charitable foundation would be the greater of 90% of the current year’s income or 90% of $280 ($252) and 80% of the previous year’s receipted income or $80. As mentioned above, a public charitable foundation can exclude “10-year gifts” from receipted income and also from income. The receipted income test reflects an attempt to keep fund-raising and administration costs reasonable. For example, if a charity has only receipted income, say $100, those costs would be limited to no more than 20% of the receipted income total or $20. The test is effective where the income of the charity is largely receipted income but it is of limited importance where the charity’s income includes substantial amounts from other sources.

The receipted income amount is not a part of the private charitable foundation’s distribution requirements (discussed below) as the potential abuses in this area are of a different nature and a receipted income test is not really required. The 80% rule is to be phased in. There are transitional rules available and the relevant percentages referred to in paragraph 149.1(2)(b), subparagraph 149.1(3)(b)(i) and subsection 149.1(5) are:20

1. 50% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1976

2. 60% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1977

3. 70% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1978, and 4. 80% where the immediately preceding taxation year is a year after 1978.

A charitable organization could transfer income from receipted donations to an associated charitable organization and fulfill the distribution requirements of subsection 149.1(2). The associated organization would then have no distribution requirement for the gift because no receipt was issued by the associated charitable organization. The only limiting factor in this case would be the fact that a charitable organization must devote all of its resources to charitable activities. However, subsection 149.1(6) defines “devoting its resources to charitable activities” to include disbursements to an associated charity. Thus, it would appear two or more associated charities could continually transfer funds back and forth fulfilling both their disbursement requirements and the requirement that all resources be devoted to charitable activities. It is unlikely that the Department would allow this kind of situation to continue and presumably the Department would revoke the designation of associated registered charities as provided by subsection 149.1(7).

Problems with the Receipted Income Test

Gifts in Kind A situation could arise where a charity receives a gift in kind which it cannot use directly in its charitable activities. It would appear that if the charity issued a receipt described in paragraph 110(1)(a) in respect of the gift it would have to bring an amount equal to the amount in respect of which it issued the receipt into its disbursement requirements. This may necessitate the sale of the gift in kind or the transfer of such gift to another charity which could use it directly.

This could cause a number of problems. For example, if a receipt were issued for the fair market value of the property at the time it was received, and if the fair market value of the property decreased before it was disposed of by the charity, the charity might not realize a sufficient amount to enable it to meet its disbursement requirement.

Donations Subject to a Trust Another hardship could arise where a charitable organization receives donations subject to a trust or direction that the property received be retained beyond the following year end. A charitable organization is required to include all donations received in its receipted donations test regardless of whether they have conditions attached. This may cause a serious conflict in what the charity is authorized to do under the terms of the trust instrument and what it is required to do to meet its disbursement requirement under the Income Tax Act. If it breaches the trust it could be subject to an action for breach of trust. If, on the other hand, it does not meet its disbursement requirement the Minister could revoke its registration and subject the charity to the penalty tax. It appears to us that the obvious solution to this type of problem would be for the Minister to permit the accumulation of the property pursuant to subsection 149.1(8).

Determination of Net Income

Income

The basic concept underlying many of the provisions in section 149.1 is

“income” and although section 9 of the Act describes a taxpayer’s income fora taxation year from a business or property as his profit therefrom for the year, it is difficult to fit a charity’s income into this concept. The income of a charity normally is not “from a business or property” and charities by definition do not have a profit motive. Therefore, trying to tie tests into “profit” does not appear to be conceptually sound. The following examples illustrate some of the problems that arise with this concept. In all of these examples we are assuming that the entity is a charity under the common law.

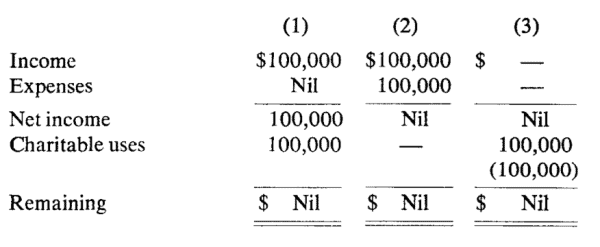

Example 1

A foundation receives $1,000 of investment income and incurs a $100 accounting fee. It has no other income or expenses and the $900 remaining is gifted to qualified donees. It would appear that the following format is reasonable:

Example 2

An active charity, a school, has $100,000 of capital. Assume the school operates one year and expends the $100,000 on school operations. It seems fairly clear that the $100,000 expenditure is a charitable use.

Example 3

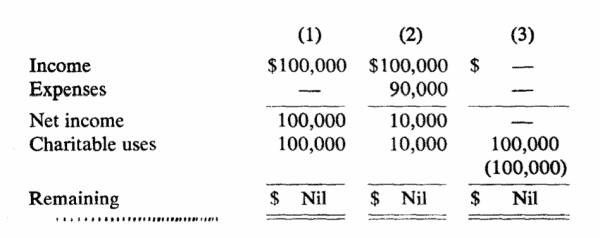

An active charity, a private school, receives tuition fees of $100,000 (100 students x $1 ,000) and expenses are $100,000. The following appear to be the possibilities:

In (1), we can say $100,000 in resources are available for charitable uses and all of these resources are expended on charitable uses. In (2), we can consider that $100,000 in fees represent income and $100,000 in expenses are incurred to earn it. In this case, net income is nil and there are no charitable uses. Or perhaps, we can say in (3) that there are charitable uses but the cost of these is nil. All three approaches seem to have some validity.

Example 4

Extend this to a private school with 90 students paying $100,000 in tuition in total and 10 needy students allowed in free. Expenses are $100,000.

Here (2) seems reasonable in that 10% of the school expenses relate to the needy students. However, it also seems reasonable to consider the full $100,000 of expenses to be charitable uses.

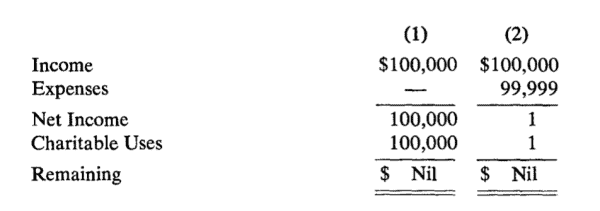

Unfortunately this is not simply an academic question because “income” is used in many of the charity tests. In addition form T3010 requires this type of information. For example, what is the category of a private school that has $100,000 in tuition fees, $99,999 in school expenses and donates $1 to United Way? The answer would seem to depend upon your concept of income.

It is the authors’ opinion that the only workable approach is (1) even though there may be some validity in the other approaches.It appears that in Case (2) the school disbursed more than SO% of its income to other qualified donees and would be a foundation by virtue of the operation of paragraph 149.1(6)(b). This does not appear to be a reasonable result.

General Expenses

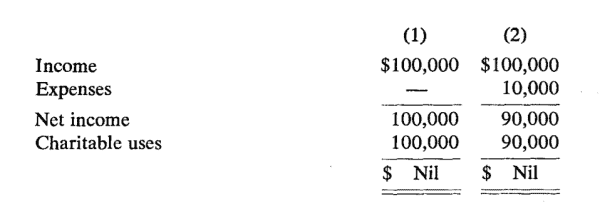

It is not always entirely clear whether certain expenditures made by a charity should be deducted in computing its net income available to be used for its charitable activities or if they should be considered to be part of the charitable activities. For example, a church collects $100,000 from its members and expends $100,000. On closer examination it appears that 10% of the minister’s time is spent on fund-raising. We now have a number of alternatives including the following:

Assuming 10% of all expenses are incurred for fund-raising, one approach would be to consider these expenses as “administration” or “other” expenses (e.g. on Form T3010). The difficulty with this approach is that in an active charity it is frequently arbitrary whether the costs are classified as charitable activity or administration. Even simple expenses such as telephone expenses and executive salaries present problems. On the surface these may appear to be administrative but they are also part of the direct charitable activity costs. Rarely ‘are the telephones and executives used solely in fund-raising or “administration”. If it really is necessary to segregate administration expenses some type of allocation process should be used. The costs could be allocated on some reasonable basis such as time spent on “administration” (whatever that is in a charity) and time spent on direct charitable activities.

A better approach would be to consider all expenses, including incidental expenditures, of most active charities as charitable activity expenditures.

A problem may arise where, for example, 90% of the expenses are incurred for fund-raising and only 10% for charitable uses. In this situation the organization is probably not a “charity” by definition and it would seem that a mechanism outside the Income Tax Act and apart from the application of a strict income test by the Department should be available to prevent this kind of abuse.

In a passive charity, such as a foundation, most expenses would be administrative and could logically be shown as such. For example, a foundation might have one million dollars in investments and the net income earned on these investments might be distributed to various qualified donees. It has no other activities. In this case most of the costs would be incurred in earning income from property and it would appear that most of these expenses would be deducted in determining net income available for distribution to qualified donees.

In reviewing completed T3010 forms it is apparent to us that it will be impossible to validly compare the performance record of charities based on the forms. For example, the form requires the charity to disclose administration and other expenses. Some charities interpret administration expenses to include only their fund-raising costs. Others include accounting, office salaries and all other administration expenses shown on the financial statements. Unless all charities include the same types of expenses under the same categories on the form, valid comparison is impossible. As this is one of the main purposes of the form, the Department should issue general instructions indicating what categories of expenses are to be included in the various sub-totals on the form.

Depreciation and Similar Expenses

Another problem in using the net income approach is that all of the normal provisions in the Act with respect to the computation of income apply. In section 18 of the Act it is stated that in computing the income of a taxpayer from a business or property no deduction shall be made in respect of … “an outlay or expense except to the extent that it was made or incurred by the taxpayer for the purpose of gaining or producing income from the business or property”22 and “an outlay, loss or replacement of capital, a payment on account of capital or an allowance in respect of depreciation, obsolescence or depletion except as expressly permitted by this Part”.23

One could argue that these provisions do not apply because, in most cases, a charity is not computing income from a business or property. This might indicate that depreciation is an allowable expense and need not be added back in computing income. However, if these provisions do apply, it would appear possible to argue that if part of the depreciation expense has to be added back, capital cost allowance could be claimed. For example, a foundation that receives investment income and passes the net income after expenses on to qualified donees might have office equipment. Depreciation on the office equipment might be added back and capital cost allowance claimed.

The same problem exists where the depreciation arises from an expenditure that was a charitable use expenditure. For example, a foundation buys and operates a bus to transport crippled children to school. It would appear that form T3010 and the disbursement requirements of the Act would require that the full amount be considered a charitable activity expenditure in the year of purchase. The disbursement requirements of the Act refer to an amount “expended” which implies that it must be “paid out”. Depreciation and capital cost allowance are not amounts “expended” and therefore it appears they cannot be claimed in the year as part of the disbursement amounts. In this example, it would only be reasonable for the Department to permit charities to use accounting depreciation or the full write-off. The Department could request consistency but it should not be necessary to add back depreciation unless the full amount has been written off “for tax purposes” at the time of purchase. Over time the particular treatment will not be significant because in the case of charities it is not a question of determining income for tax purposes on a yearly basis as in the case of profit-oriented entities but rather the use of available resources. The charity should be judged on a review of its operations as a whole over a period of time.

Personal Benefit

The definitions of a charitable foundation and a charitable organization in paragraphs 149.1(l)(a) and 149.1(l)(b) respectively require that no part of the income be payable to, or be available for, the personal benefit of any proprietor, member, shareholder, trustee or settlor. Income in this concept is not gross income but net income. The expenses deducted in determining net income could include expenses such as a salary or payment to a member for legitimate services rendered to the organization so long as they were reasonable.24 Similarly, a payment could be made in carrying out a direct charitable activity for services rendered or costs incurred. However, no part of the income, in particular the “profit” or surplus remaining after legitimate expenses and costs of charitable activities, can be payable to or otherwise available for personal benefit.

This restriction is also a standard requisite in the letters patent, constitution or trust document of the charity. For example, the Department in Information Circular 77-14 states that a constitution must include a clause stating that the charity shall be carried on without purpose of gain for its members and any profits or other accretions to the charity shall be used in promoting its objects, and a trust document must include an article in which assurance is given by the trustees that all the monies received will be expended only for the purposes outlined in the trust document.

Charitable Uses

Once net income, or in certain cases receipted income, is determined, the charity must expend in the year a minimum amount on charitable activities carried on by it and by way of gifts made by it to qualified donees. “Expend” generally means “pay out” and a cash basis seems to be implied. This would normally preclude a charity accruing charitable grants or charitable activities as liabilities. Frequently, there is no legal commitment to pay the grant in which case the amount would also not be included in the financial statements. Often these commitments are disclosed by a note to the financial statement. However, where there is an obligation to pay an amount it would seem that the Department should not be overly concerned if the charity did accrue a liability, was consistent from year to year, and did, in fact, pay the amount out during the following year.

Obviously, a charity should not be allowed to accrue amounts where there is no real liability and no intent to pay the amount as this would defeat the disbursement tests.

Amounts expended on direct charitable activities may be difficult to identify and the same problems discussed above with respect to administration expenses arise. It may be necessary to allocate expenses and costs, where this is the case, on some reasonable basis. Many costs, however, are clearly direct charitable activity costs and there should be no problem in identification.

By definition, a charitable organization must devote all of its resources to charitable activities carried on by the organization itself. This would appear to preclude a charitable organization making gifts to other charities or qualified donees. However, subsection 149.1(6) expands the meaning of devoting resources to charitable activity by including:

I. the carrying on of a related business 2. disbursements of not more than 50% of the income for the year to qualified donees, and 3. disbursements of income to a registered charity that the Minister has designated as a charity associated with it.

This extended meaning allows a charitable organization to make gifts, within certain limits, to other qualified donees. It would appear that if the charitable organization disburses more than 50% of its income to qualified donees other than associated registered charities it would no longer be a “charitable organization” by definition. Presumably, it would be considered a charitable foundation in this circumstance. The charitable organization and the charitable foundation h::1xc different disbursement requirements and other requirements. As a result, a charitable organization must watch this 50% cut-off to ensure that it does not accidentally become a charitable foundation where the organization is making gifts to other qualified donees. Where funds are transferred between charities that have substantially the same aim or objective, consideration should be given to seeking associated status (see above).

“Qualified donee” is defined in paragraph 149.1(1)(h) to include a donee described in any of subparagraphs 110(1)(a)(i) to (vii) or paragraph 110(1)(b). Both the charitable organization and the charitable foundation will frequently not know if the donee is qualified and it may be necessary to clarify this with the donee before the gift is made.

Non-Qualified Donees

Occasionally, a charity wishes to benefit a non-qualified donee and a question will arise as to whether the gift will be an acceptable charitable use. This problem frequently arises where the donee is a local group that is not a registered charity or otherwise qualified. In this type of situation it may be possible for the donor charity to consider the gift a “contracting out” of a charitable activity. When a charitable activity is contracted out, the donee group, in effect, uses funds received from the donor charity to carry out a charitable activity on behalf of the donor. The donor charity would direct the use of the funds and receive an accounting of their disposition. A charity must be able to carry on direct charitable activities itself if it is to “contract” them out. If the constitution precludes this, the Department would probably not recognize such disbursements as part of the disbursement requirements. This concept of “contracting out” is not specifically provided for by the legislation but it seems to be a reasonable solution where gifts are made to non-qualified donees.

This would only apply if the gift was for a purpose which was charitable under the common law. This would be reasonable as flowing funds through a registered charity should not make a gift eligible which would otherwise not be eligible under paragraphs 110(1)(a) or (b) if given directly by a taxpayer to a non-qualified donee for a non-charitable purpose.

Gifts to non-qualified donees can also arise where a registered charity makes gifts overseas, for example, to a charity in another country. It may be more efficient and politically acceptable for the foreign charity rather than the Canadian charity to carry on the direct charitable activity itself. The same factors discussed above would apply but in addition it is understood that the Department requires the Canadian source be publicized as much as possible in the foreign country. Where gifts are made to another charity not resident in Canada and there is no control or direction over the use of the funds there may be some difficulty in persuading the Department to recognize the gifts as part of the disbursement requirement.

Special Provisions

Special relieving provisions are available in determining compliance with the disbursement requirements and a charity may find these provisions helpful. However, all these provisions contain a number of restrictions which can cause some difficulty.

Averaging:

Subsection 149.1(5) allows averaging in meeting the receipted income requirements of paragraph 149.1(2)(b) and subparagraph (3)(b)(i). This averaging cannot be used in meeting the 90% of income test. The provision allows the charitable organization or public charitable foundation to average the amounts it has disbursed over a period which includes the current year and up to the four preceding years in determining compliance with the receipted income test.

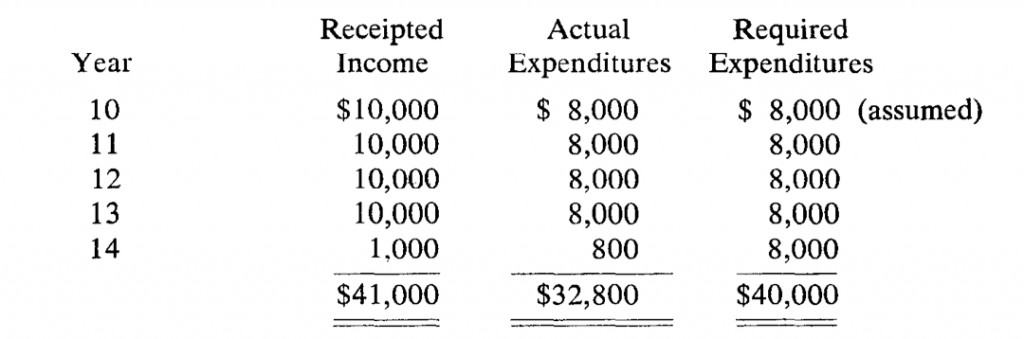

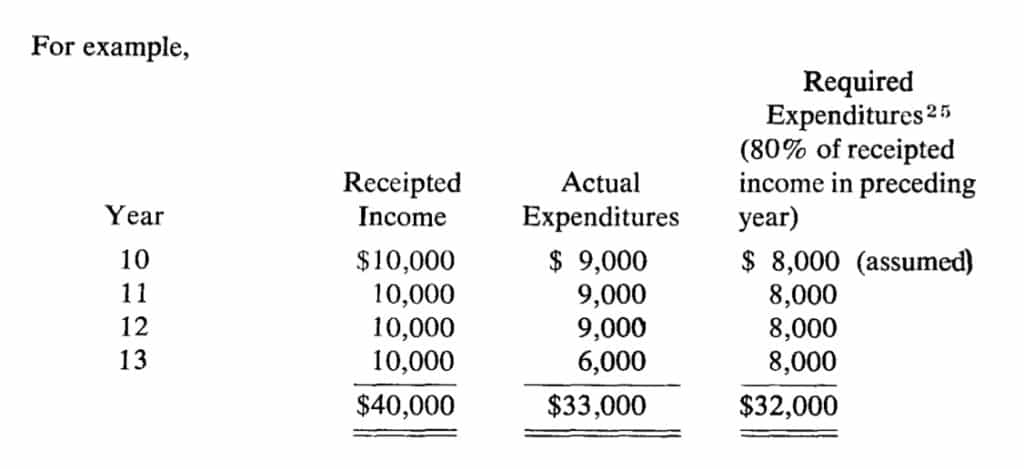

In Year 13 the charity did not expend 80% of the preceding year’s receipted income. The charity might then check a cumulative test based on the current year and up to the four preceding years. In this example we have used the current year and 3 preceding years. Actual expenditures are $33,000 and $32,000 are required. The charity meets the test on a cumulative basis.

However, consider the following situation:

The charity has expended 80% of receipted income each year on a current basis. However, because the test is based on 80% of the preceding year’s receipted income the required expenditure in Year 14 is $8,000. In this situation averaging does not work as actual expenditures are $32,800 and required expenditures arc $40,000. The charity did not meet its disbursement requirement.

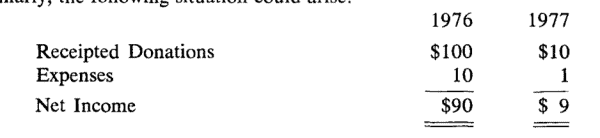

Similarly, the following situation could arise:

In 1976 the charity spends 100% of its income on its own charitable activities. In 1977, it is required to expend 50% of the preceding year’s donations (50% of $100 or $50). The charity does not have these funds as it used them in 1976. Subsection 149.1(5) would not apply because the reference is to taxation years subsequent to 1976. That is, it cannot average 1976 and 1977 because 1976 is not a taxation year subsequent to 1976.

It should be noted that the Minister has discretion whether or not to revoke the registration of a charity and each situation, it is hoped, would be reviewed on a case by case basis to determine if registration should be revoked.

It should also be noted that subsection 149.1(5) refers to “the relevant percentages of those amounts for which it issued receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a) …“It is not clear in the case of a charitable foundation that “10-year gifts” would be excluded in determining these amounts.

Carryforward

A charitable organization or charitable foundation may carryforward certain excess expenditures in determining compliance with paragraphs 149.1(2)(b), (4)(b) or subparagraph (3)(b)(ii). For example, a charitable organization has receipted income in Year 1 of $10,000 and in Year 2 it expends $15,000. Its disbursement requirement in Year 2 is 80% of $10,000 or $8,000. The charity can carryforward part of this excess and count it as an expenditure in any of the following three years in determining compliance under paragraph 149.1(2)(b). However, there are a number of restrictions which should be noted.l. Prior approval in writing is required before the excess disbursement is made.26

2. The disbursement must be for a particular purpose specified in the approval. 27

3. The Department may impose certain conditions.n 4. The disbursement excess is defined in subsection 149.1(21) and only this amount is eligible to be carried forward. In the case of a charitable organization this is the amount expended in excess of the total receipted income of the immediately preceding taxation year.28 In the example given this is $5,000 rather than $7,000, the difference between the required disbursement and the actual disbursement. In the case of a charitable foundation, the amount that can be carried forward is the amount expended in excess of total income rather than 90% of income. Income is computed without regard to the reserve system described below.30

It might also be noted that the carryforward applies only for determining compliance under subparagraph 149.1(3)(b)(ii) or paragraph 4(b) in the case of a charitable foundation. For example, it could not be used with respect to subparagraph 149.1(3)(b)(i).

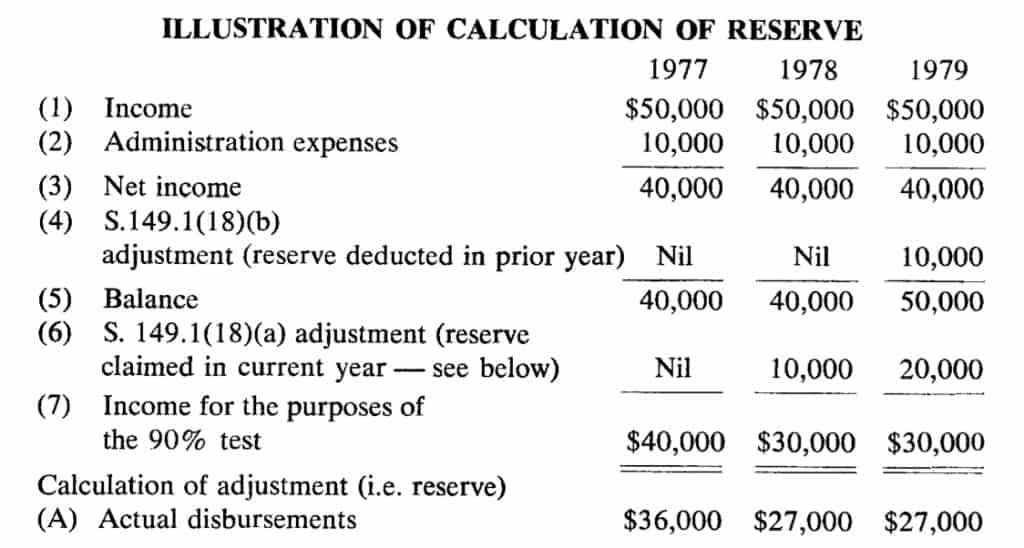

Reserve Systems In computing the income of a charitable foundation for the purposes of subparagraphs 149.1(l)(e)(ii) or (3)(b)(ii) an amount, not exceeding its prior year’s income, may be deducted,31 and any amount so deducted in one year must be added back to income the following year.32 The following example illustrates the use of this reserve.

Another reserve is provided in subsection 149.1(19) and it applies in the first taxation year after incorporation or creation of a charitable foundation. The charitable foundation can treat the whole or any part of the amounts spent in the second year as having been spent in the first year in detc rmining compliance with the requirements of subparagraph 149.1(3)(b)(ii) or paragraph 149.1 (4)(b). In effect, this in combination with subsection 149.1(18) allows a charitable foundation to carryforward a reserve equal to the previous year’s income.

Both reserves (i.e. subsections 149.1(18) and (19)) are applicable only for charitable foundations. It might be noted, however, that the receipted income test of a charitable organization 33 or a public charitable foundation 34 is based on the preceding year’s receipted income so in effect a one year carryforward is also available here.

Some care must be used in taking full advantage of the reserves in subsections 149.1(18) and (19) because the maximum reserve permitted is the preceding year’s income. For example, a “short year” could result in low income in a year which would reduce the reserve available for the following year. Similarly, where there is considerable variation in income from one year to the next, the maximum reserve may not be sufficient in a high income year following a low income year.

Permission to Accumulate Funds

A charity must expend a minimum amount each year which in many cases limits the funds that can be retained for special purposes. Normally, only a small amount could be saved each year given the disbursement requirements. However, subsection 149.1(8) provides special relief in that a charity may apply to the Minister for permission to accumulate property and, if permission is granted, such property and income earned in respect of that property will be deemed to have been expended on charitable activities carried on by it in the year in which it was accumulated.

Should the property and income not be used as agreed upon, it would be deemed to be income of the charity for the taxation year in which it became apparent that the terms and conditions would not be met.35 An interesting question arises where permission has been obtained to accumulate property received as a gift in kind. If it is later determined that the property cannot be used by the charity subsection 149.1(9) deems “the property to be income”. It is not clear what value would be brought into income where the value has changed—the value of the property at the date it was received by the charity or the value thereof at the date it was brought into income.

One problem with this provision is that the Department must approve the accumulation. This requires a “particular purpose” satisfactory to the Department. A charity may wish to accumulate funds to meet potential emergencies in the future or for general purposes. It is unlikely that the Department would approve general requests and we suspect that charities will not receive blanket approvals with respect to the accumulation of capital or general funds. Hopefully, the Department will review each situation on a case by case basis and not be overly restrictive. It is expected that certain conditions will attach to the approval and that there will be additional reporting requirements with respect to the accumulating funds. We would also expect timing restrictions to be imposed.

No form is prescribed for applying for permission to accumulate, but the Department’s approval must be in writing. We suggest a letter be sent to the Department at the address given in Appendix A containing full details on the specific project including estimated costs, the time span needed to accumulate, total expected to be raised by donations, etc. Other background information might be helpful.

Private Charitable Foundations

The income of a private foundation is calculated in the same manner as a public foundation. However, the disbursement requirement is quite different in that the receipted income total is not used. Private foundations do not normally incur significant fund-raising costs and the potential abuses in this type of charity arise from the non-arm’s length nature of the foundation which permits a donor to retain a measure of control over monies given away.

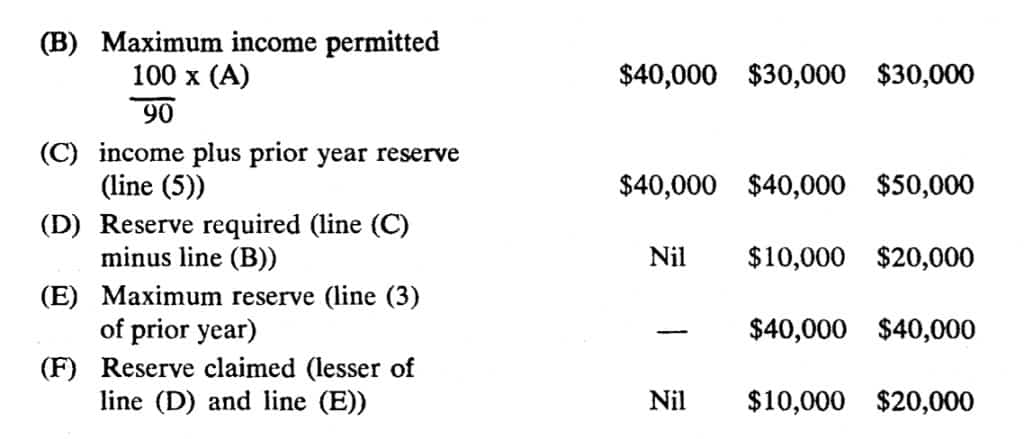

A private foundation must expend an amount at least equal to the total of: (A) the greater of

(i) 5% of the fair market value of certain capital properties (“non-qualified” property) calculated as of the commencement of the taxation year and

(ii) 90% of the income derived from these properties and

(B) 90% of the amount by which the total income of the foundation exceeds the income derived from the properties described in (A).

This test ensures that the private foundation pay out an amount computed by using a reasonable return on assets.

In this example the foundation must expend on charitable uses more than its actual income. The result is that the foundation would have to sell some of its non-qualified property, pay out capital or increase its return on nonqualified property.

The purpose of the test is straightforward in that it ensures a minimum return on investments. For example, without this test a foundation could be set up by A and if A was the sole owner of a private company, it could be used by him as a source of cheap financing for the private company. This was a fairly common type of abuse in the past but now there must be at least a 5% return. A number of problems can arise because of this test even with arm’s length investments. Non-qualified property includes all capital properties except capital properties used directly in charitable activity or administration, property accumulated with the consent of the Minister pursuant to subsection 149.1(8) and qualified investments. Qualified investments are defined in paragraph 149.1(1)(i), a copy of which appears in Appendix B. It should be noted that in paragraph 149.1(1)(i) reference is made to a share in the capital stock of a public corporation, or a bond, debenture, note or similar obligation of a corporation the shares of which are listed on a prescribed stock exchange in Canada. Shares of private corporations and foreign corporations are not qualified investments. It may be that the foundation would have to sell its foreign investments at a loss if they are not returning at least 5%.

A situation may arise where a private foundation owns shares of a private company which in turn holds shares of a public company. The shares of the private company would not be qualified investments and the private foundation would have to ensure that it receives at least a 5% return.

The most common non-qualified capital properties held by private foundations are land, private company shares or debt and foreign investments (e.g. U.S. companies). A problem will frequently arise in trying to determine the fair market value of these properties. The 5% of fair market value is calculated as of the commencement of the taxation year. For example, a foundation might estimate fair market value to be $100 and distribute 5% of this amount. If itis subsequently determined that the fair market value is $110 the foundation may not have met its disbursement quota. It may be advisable where there is doubt as to the fair market value of a non-qualified investment to usc a higher payout percentage (i.e. 7-10%) to provide a safety factor. Given the severe penalty that could be imposed and the inflexibility of the 5% requirement, a foundation may not know that it did not meet the 5% payout requirement until the Minister gives notice to revoke. Appeal procedures are very limited.

It should be noted that the amount is calculated at the commencement of the taxation year. There is no relief where the foundation has a “short” year.

Careful consideration must be given to all non-arms’ length transactions with a private foundation to ensure that there is no basis for the Department to argue that a benefit has been conferred on any proprietor, member, shareholder, or settlor thereof. For example, a 3% $1,000 note of a private corporation may not have a fair market value of $1,000 and if the private foundation paid $1,000 for it a benefit may have been conferred. In such cases it may be necessary to discount the note. The 5% return is based on the fair market value of the note and not necessarily the face amount. It is not clear what the result would be if the note was a demand note because generally such notes are not discounted.

Where a foundation owns non-qualified investments that do not return 5% it may be possible to sell qualified investments and re-invest the proceeds in nonqualified investments (e.g. foreign investments) paying in excess of 5%. This would allow averaging in the non-qualified investments which, because of the wording in the disbursement quota, could not be done where there is an excess in the return on qualified investments but a short-fall in the non-qualified.

The amount based on 5% of fair market value is calculated as of the commencement of the taxation year. We assume that this means the first day of the taxation year. Non-qualified porperty held on that day would be taken into account even if sold shortly thereafter and the funds re-invested in qualified property. The property may not have earned any income and may have been disposed of in the year although it would still form part of the base amount. As a result a foundation will have to carefully consider the timing when non-qualified property is received or disposed of.

It had been suggested that the 5% figure be allowed to fluctuate from year to year to take account of changes in the market yield. However, in countries that do use a fluctuating percentage, there are indications that a fixed rate, as long as it is reasonable, would be more desirable.36

Transitional rules are available in the calculations of the amount to be disbursed. For 1977 taxation years commencing in 1976, zero per cent is used, for 1977 and 1978 taxation years commencing in 1977, 3% and in respect of all other 1978 taxation years, 4%.

Carrying on a Business

The registration of a charitable organization or public foundation may be revoked if the charity carries on a business that is not a related business of that charity.37 A private foundation may not carry on any business.38 Restrictions on the carrying on of a business by a charity can easily be justified. If funds could be accumulated tax-free and used to finance its business, the tax-exempt charity would have an unfair advantage in competing with nonexempt business. In addition to the unfair competition it is possible to envisage situations where charities devote so much time to business activities that the charitable activities suffer. Further, potential tax revenue is lost when a business is operated by a tax-exempt charity.

The problem facing the lawmakers was that many charities do have a legitimate reason for carrying on a business and it was necessary to allow this type of activity. The government recognized this problem and in the discussion paper, The Tax Treatment of Charities, tabled with the June 23, 1975 budget, noted:

“The government recognizes that many registered charities do have good reasons for carrying on a business. An art gallery may have a gift store. A hospital may have a cafeteria for visitors. Certain groups sell used clothes and other items. In recent years the law has been administered to allow such enterprises if the business is directly related to the charitable activity of the organization.

It is proposed to amend the Income Tax Act to allow both charitable organizations and public foundations to carry on a business related to the primary charitable activity. This provision would make clear that the test would not be the fact that the income earned by the business is used for charitable purposes, but rather that the business is a usual and necessary concomitant of the charitable activity.”

The new legislation does this by allowing the carrying on of a “related” business by a charitable organization and public foundation. As mentioned above a private foundation cannot carry on any business. It is interesting to note that a charitable organization will be considered to be devoting its resources to charitable activities carried on by it to the extent that, among other things, it carries on a related business. 39 This precludes the argument that the charitable organization is not devoting all of its resources to charitable activities carried on by the organization itself as required by paragraph 149.1(1)(b) if it carries on a related business.

Although the restrictions on business activities are justified, a number of problems in interpretation will arise. In particular, the meaning of “related business” should be clarified and guidelines on the Department’s interpretation of “carries on business” with respect to a charity should be issued. It has been rumoured that an Interpretation Bulletin on the subject is being considered but nothing has been released as of the date of this article.

“Related business” in relation to a charity is defined in paragraph 149.1(1)(j) to include a business that is unrelated to the objects of the charity if substantially all of the people employed by the charity in the carrying on of that business are not remunerated for such employment. This eliminates the problem which might otherwise arise in many charity fund-raising projects. If substantially all of the people employed in such projects are volunteers, as is often the case, there should be no problem. A problem still remains where the people employed are remunerated.