This article has been developed from a presentation to The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy’s Fourth Grantors’ Conference for Foundations on June 17. 1986, in Toronto. The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution to this article of the late George Blodgett.

Whether they were established to further the cause of the arts, social services, medical research, or some other worthy cause, charitable organizations must accept financial stewardship obligations to their donors. Directors must make themselves responsible for ensuring that their organizations are able to generate all the funding they require and that monies received are spent efficiently for the stated purposes of the organization. In other words, directors must be accountable to donors for their spending.

Similarly, it is incumbent upon members of the board of directors of a charitable foundation or any governmental or private-sector agency distributing funds to non-profit organizations, to satisfy themselves that those financial stewardship responsibilities are being met and that the funding of any project of a given applicant is an appropriate activity for the granting organization they serve.

Introduction

In order to achieve fully the financial stewardship objectives and funding objectives of both the grantors and the grantees, the financial information of organizations seeking funding must be available in a relatively easy-to-read form so that readers of the financial statements can grasp how effectively the organization has managed its operations and finances in the past. Budget information (together with assumptions) in respect of future activities is useful in assessing the potential for future financial success or failure. In addition, relevant statistics (e.g., clients’ services, pieces of information distributed) on past and future activities should be provided.

From the grantor’s perspective, the grants officer or other individuals involved in determining whether projects are worthy of support must obtain sufficient financial information in order to answer at least the following questions:

1. Is the applicant qualified to meet the need that is perceived and which is the object of the grant application?

2. Does the applicant need the support of the grantor or are other avenues for such support more appropriate?

3. What is the extent and form of the support being sought, including whether it is funding for a one-time project or a continuing service for which alternative sources of funding will eventually be necessary?

By examining the financial statements that are generally available as well as any budget information that is required, a grants officer should be able to obtain a considerable amount of pertinent financial information and to answer the above questions and others that may arise during the course of the proposal-evaluation process.

The financial statements of a fund seeker provide a financial picture, taken at a particular point in time, of the charitable organization’s operations for the period covered by the financial statements-generally one year. It should be noted, however, that obviously the financial statements only reflect transactions of a financial nature and do not cover a variety of activities which have no financial implications such as activities carried on by volunteers without any financial costs.

Financial Statements

The preparation of the financial statements is the responsibility of the officers and employees and ultimately the board of directors of the charitable organization. Normally, most applicants for funding from charitable foundations will have had their financial statements audited by a chartered accountant who is independent of the charitable organization and its officers and board members.

The auditor may offer suggestions as to the presentation of financial information in the financial statements and what information should be included or excluded, but it should be kept in mind that the financial statements are those of the organization and not the auditor. However, the auditor is responsible for the auditor’s report which will explain reservations, if any, with respect to the financial statements.

The audited financial statement of a charitable organization almost always includes the following (described in greater detail later):

1. Statement of Revenue and Expenses

This statement shows how much revenue the organization has received (or had receivable) during the audited period and, generally, the sources of that income. It also shows the expenses incurred during the same period, and the amount by which the revenue exceeds expenses or vice versa (either operating surplus or deficit) during the period. Revenue and expenses of special funds may be presented separately from the general operations (see Appendix 1).

2. Balance Sheet

This statement is similar to an instant photograph of the financial position of an organization at a particular point in time. The balance sheet will present the organization’s financial situation as it existed on the last day of the fiscal period (usually a year) under review.

3. Statements of Surplus, Reserves and Special Funds

Such financial statements will also include the changes in the accumulated surplus of the organization during the period, any changes in the reserves or appropriations of surplus and alterations in any special funds.

4. Statement of Changes in Financial Position

This statement, in effect, provides a link between the statement of revenue and expenses and the balance sheet. It shows the sources of funds received during the period, how the funds were used, and the magnitude of the increase or decrease in cash resources during the year.

5. Notes to the Financial Statements

Almost all audited statements include a number of notes designed to outline the accounting principles used in preparing the statements and to clarify certain of the items appearing on them.

It is important to realize that these notes form an integral part of the financial statements and are vital to a proper understanding of the financial information contained in the statements.

6. Auditor’s Report

As noted above, the auditor’s report is the only part of the financial statements that is not the responsibility of the charitable organization. In the report, the chartered accountant expresses an opinion about the financial statements based upon the results of his or her examination.

In the grant-approval process, the grantor’s initial review of a charitable organization will usually involve an analysis of the audited statements of the past three years and of the expectations for the succeeding year (or years) as reflected in the budget approved by the board of directors.

Analysis of Statement of Revenue and Expenses

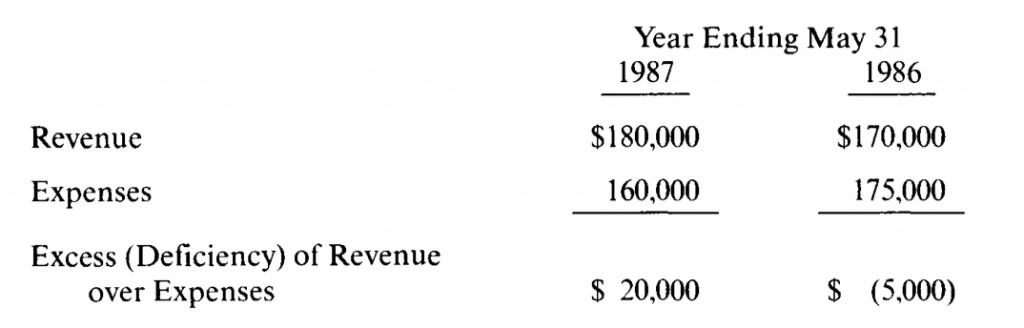

Completely condensed, such a statement will provide the information found in this sample:

If the above were the only information available, the statement would not indicate very much and would have to be considered meaningless. A surplus was achieved in 1987 in the amount of $20,000 whereas there had been a loss of

$5,000 in 1986. We can see that revenue increased $10,000 to $180,000 and that expenses fell by $15,000, but beyond that we learn nothing. Fortunately, most revenue and expense statements provide considerably more detail and are able to make us a little wiser.

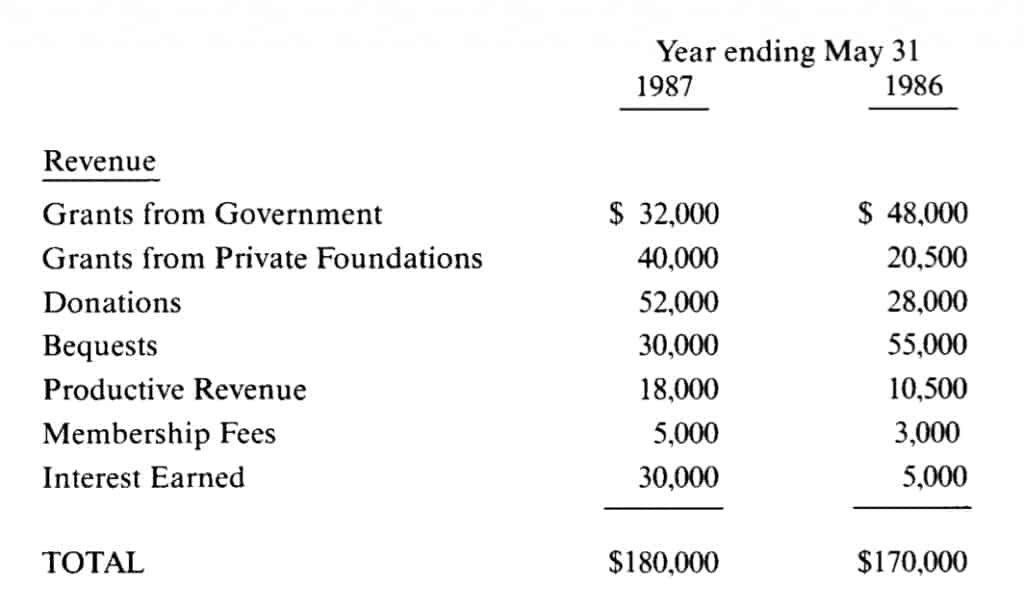

A typical statement would probably show the following information with respect to revenues:

With this breakdown of revenue we can learn far more. In particular, we learn immediately that the increase of$10,000 in total revenue was not simply a case of each revenue source providing a little more. Rather, it was due to a combination of factors, some positive, some negative.

This breakdown thus helps considerably, but as is often the case, it may still not be in sufficient detail to answer all the questions that should be asked by those who are analyzing the revenue of the charitable organization. Very often it will be necessary to ask questions, the answers to which may lead to more questions and/or interpretation thereof so as to learn more about the sources of revenue. More detailed breakdowns can usually be supplied by the charitable organization and, in total, this information should be verified by comparison with the audited statements.

What are the questions which should be asked about a charitable organization seeking a grantor’s support? To begin, public and private acceptance of the need for the organization’s services can be measured, at least in part, by looking at the components making up the total revenue. Some of the important revenue categories and the types of questions that arise from them, are as follows:

1. Government Grants

Income from governments at the federal, provincial or municipal level is an important factor for many organizations. In our example, government grants fell from $48,000 in 1986 to $32,000 in 1987. Obviously, some questions should be asked:

– What portion of grant revenue was federal, provincial and municipal?

– Where and why was there a reduction?

– What portion of the revenue consisted of sustaining grants and how assured is their continuance?

– How much revenue is received on a fee-for-service basis (e.g., the government is purchasing services for individuals from the organization) and is any change in government policy contemplated which could jeopardize this revenue in the future?

– How much revenue was received for specific projects with a limited lifetime?

2. Private Sector Fund Raising

Private sector fund raising includes money raised through appeals to foundations. corporations and individuals, special events of a fund-raising nature and bequests. It could also include membership fees where such fees are solicited from members of the general public.

The level of private sector fund raising and the direction in which it is moving is an important indicator of public acceptance of the charitable organization’s services. In our example, revenue from governments went down in 1987 but this decline was more than offset by increases in private sector fund raising. Grants from private foundations almost doubled (to $40,000) and donations from the public increased by $24,000. Bequests were down, but they are of course, difficult to predict on a year-to-year basis.

The level of private sector fund raising and the potential that exists for increased private support, assume special importance when funds are being sought for a program or activity which will continue to operate indefinitely. The grant contemplated may be sufficient to cover costs for several years, but after that the organization will be on its own. Unless private sector fund raising can be increased sufficiently to offset the eventual loss of grant monies, the project may have to be abandoned. Satisfying the grantor that it can generate the funds needed to carry on a continuing program is thus a major responsibility for any organization looking for seed money.

3. Other Revenue

This category of revenue includes such items as fees for services provided to clients, investment income. the manufacture and sale of products carried on as a profit-making venture to supplement the organization’s income and any miscellaneous items.

Investment income includes any interest or dividends received on investments. It also includes interest earned on free cash balances and some assurance should be received that the organization is maximizing the return on any idle funds. This is particularly true when a grant is being contemplated for a project which will not be fully implemented for some time. You may wish to inquire whether the organization has an investment committee with outside expertise to provide guidance for maximizing returns on investments.

Similarly, the expenses of the organization will be outlined in some detaiL usually on a functional basis by program or project for which the costs were incurred, or by the nature of the expense (e.g., salaries, rent, etc.).

If the breakdown is by program or project, the section on expenses in our example might appear as follows:

Depending on the type of information required, an examination of the expenses, as presented in the statements and any added schedules, may not provide all the necessary information. Therefore, it may be necessary to seek from the organization additional analyses of expenses. As in the case of revenue data, such analyses should be verified by comparison to the total audited statements.

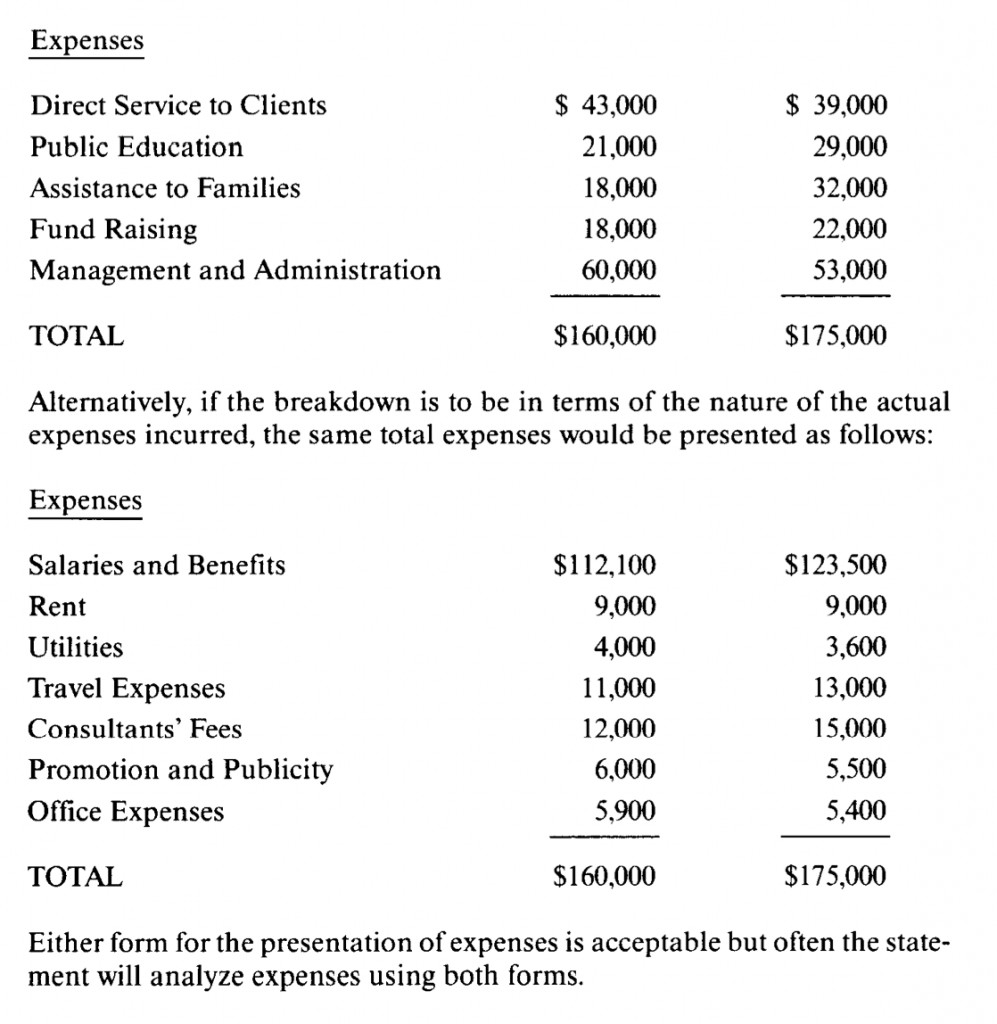

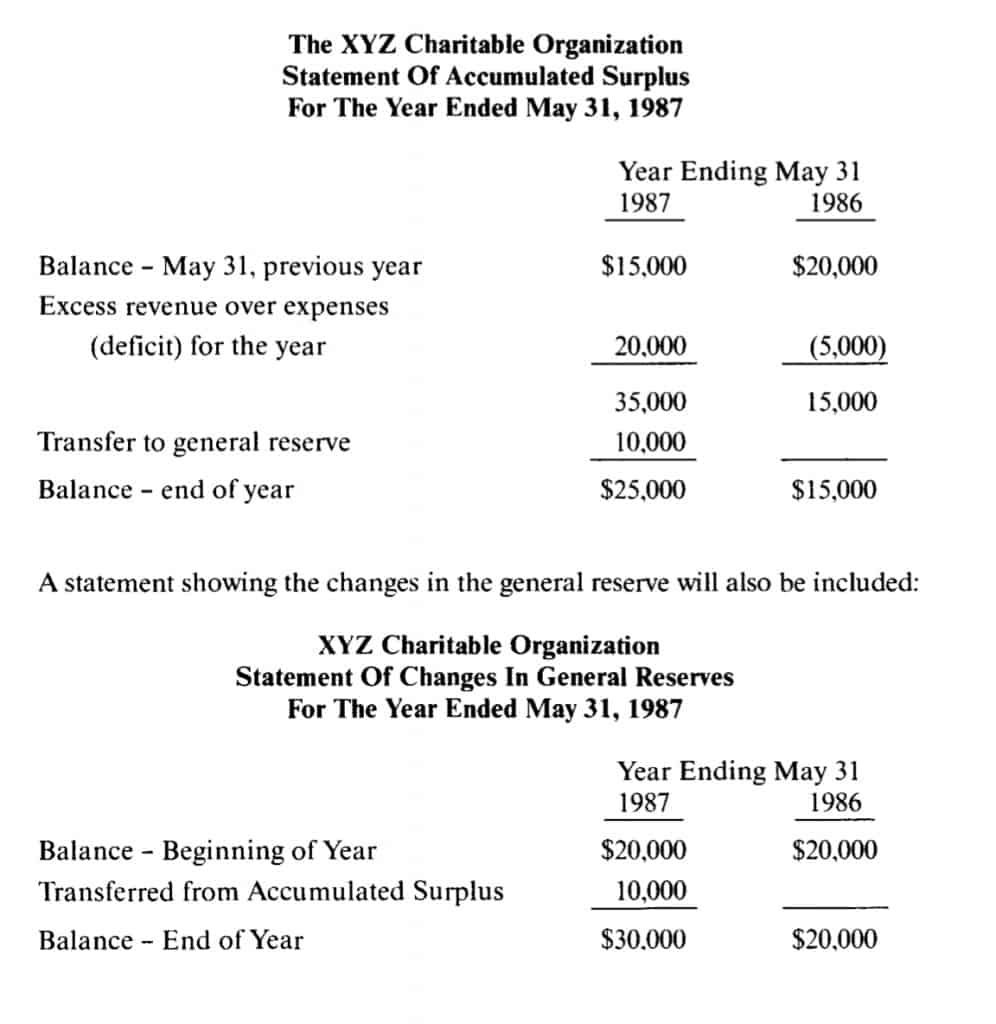

Note that the statement of revenue and expenses summarizes the results of operations for the year by showing the excess (or deficiency) of revenues over expenses for the period covered by the statement. This surplus (or deficit) will be added to (or deducted from) the prior years’ accumulated surplus of the organization, and a separate statement will usually be included showing changes in that accumulated surplus during the year. That statement might appear as follows:

An analysis of the statements of revenue and expenses over three or more years permits some recognition of trends in revenue and expenses and provides some measure of the reasonableness of the organization’s projections for the budget of the following year (and possibly future years).

On the revenue side, it may be of interest to assess changes in the organization’s degree of dependence on government support and support from the private sector; to assess whether continuing deficits are occurring which might be eroding the organization’s ability to continue existing programs or take on new ones; or simply to get a better “grip” on the organization’s fund-raising capabilities.

On the expense side, the trends in salaries and other expenditures relative to inflation and to revenue changes should be considered and unusually large variations from year-to-year in particular expense categories should be explained.

As a part of the analysis of the revenue and expense statement of a charitable organization, certain ratios and comparisons are also useful. Among these are the following:

• A comparison between the cost of activities directly related to the purposes of the organization and the costs incurred simply to maintain the organization. In our example, fund raising, management and administration were 48.75 per cent of the total costs-up from 42.8 per cent in the previous year. With the loss recorded in 1986, total expenses were reduced in 1987, but the cuts were made in the direct services area, primarily public education and assistance to families.

• An examination of the ratio of professional staff to support staff. For example, are two support staff members needed for every professional?

• The ratio of fund-raising costs to funds raised. For example, is $100 spend on fund raising producing $200 in donations? In what type of fund raising is the organization involved?If a major portion of the activity has been focused on acquiring new donors through direct mail the expense versus revenue ratio will be different than if it is receiving continuing donations from previous donors (including corporations).

Depending on the organization, other ratios and comparisons will be of interest and their nature will often become apparent as the analysis proceeds.

Analysis of the Balance Sheet

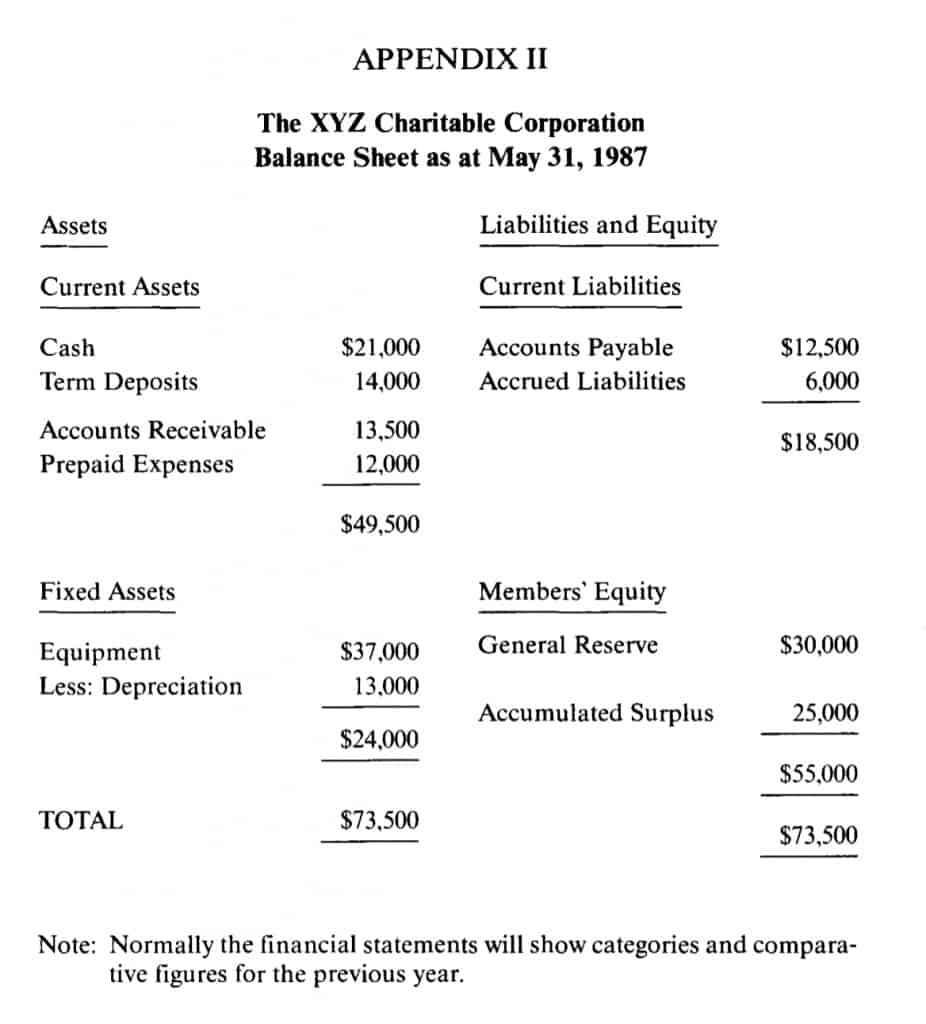

The balance sheet of any organization will summarize (in dollars) its assets, liabilities and members’ equity. A very simple balance sheet for the organization in our example is shown in Appendix II.

The assets, listed on the left-hand side of the balance sheet are usually listed under the headings Current Assets and Fixed Assets as well as, possibly, Other Assets.

Current assets consist of cash and those items which would be convertible into cash within one year.

Fixed assets consist of land, buildings and equipment used by the organization in carrying on its operations but which will not, in the ordinary course of events, be converted into cash. In many charitable organizations, fixed assets are treated as expense items and written off when they are purchased. In such cases, they will not appear on the balance sheet. In other cases, fixed assets are recorded at cost and periodic charges for depreciation are recorded in the expense section of the statement of revenue and expenses. These charges reduce the dollar amount at which the assets are carried so that the accumulated depreciation appears on the balance sheet (as in our example) as a deduction from the cost of equipment.

Liabilities, shown on the right-hand side of the balance sheet, are listed under the headings Current Liabilities and Long-Term Liabilities.

Current liabilities include bank overdrafts or loans payable on demand, accounts payable, accrued liabilities which are not yet due and, in general all existing liabilities which will have to be paid within one year.

Long-term liabilities (there are none in our example) are those obligations which will not be paid until future years. They include mortgages on properties or any other long-term loans the organization may have. Note that the portions of mortgages or long-term loans falling due within one year will be included in the Current Liabilities section of the balance sheet.

Also shown on the right half of the balance sheet is the members’ equity in the organization. This members·equity consists of the total assets minus the total liabilities-in our example. $73.500- $18,500 or $55,000. The equity consists of any capital which may have been contributed when the organization was established. plus any reserves or surpluses accumulated since incorporation and still not used. In our example. there is a general reserve of$30,000 and an earned surplus of $25,000: supporting statements on both show the changes during the year.

It can happen. of course. that the liabilities of an organization exceed its total assets. In such a case. the members’ equity amount will appear as a negative item on the right-hand side of the balance sheet.

The term ”balance sheet”. in fact. derives from the fact that the two sides must add up to the same amount. Thus. this equation must be satisfied:

Total Assets = Total Liabilities + Total Equity

An examination of the balance sheet is an important part of the financial assessment of an organization. Some of the items to be examined carefully are the following:

1. The relationship between the current assets and the current liabilities.

The excess of the current assets over the current liabilities is referred to as the “working capital” and indicates the ability of the organization to meet the financial demands of its current operations.

2. The composition of the current assets.

It there surplus cash on hand which could be earning higher interest if invested? (In our example probably not.) Are accounts receivable being collected diligently?

3. Fixed Assets

Are the present premises owned or rented? Are they sufficient to meet the organization’s needs for the foreseeable future or might it need expansion which will strain its resources?

4. Long-Term Liabilities

If the buildings owned by the organization are mortgaged, are the terms manageable and fixed for a reasonably long period at the current rate?

5. Members’ Equity

What reserves has the organization provided for specific purposes? These amounts may have been set aside by the directors out of the accumulated surplus or they may have been given by donors for specific purposes. In our example, the organization has only a general reserve and the directors of the organization would be free to apply it for any legitimate use.

What is the relation between the equity of the organization and its current level of expenditures (net of any fee for services, etc.)? This is a useful ratio to examine but in measuring the equity for this purpose, it is advisable to deduct two items from the total equity. One is the total of the restricted reserves, i.e., those reserves that cannot be used for other uses. The other is the net equity in fixed assets, e.g., the total of the fixed assets on the lefthand side of the balance sheet less any mortgages against them.

In our example the net equity determined in this manner would be the total equity ($55,000) less the equity in fixed assets ($24,000), or $31,000. No deduction would be made for reserves since we assumed that the general reserve of $30,000 is not restricted as to use.

This net equity can be divided by the total expenditures of the last complete year, then multiplied by 12. The result will give, in months, the period for which the organization could cover its expenditures even if all of its funding sources were to disappear. It is a useful measurement of the financial health of an organization. In our example it would be $31,000 divided by $160,000 multiplied by 12 or 2.32 months-not indicative of either a weak or a strong position.

These questions do not, however, represent an all-inclusive guide to the financial analysis which should be undertaken by a grantor contemplating a grant to a charitable organization. In particular, no attention has been given to the most important financial analysis, that is, an analysis of the particular project(s) for which the monies are requested.

The discussion has, however, shown how an understanding of a charitable organization’s financial situation can be gleaned from a proper reading of its audited financial statements.

Fund Accounting

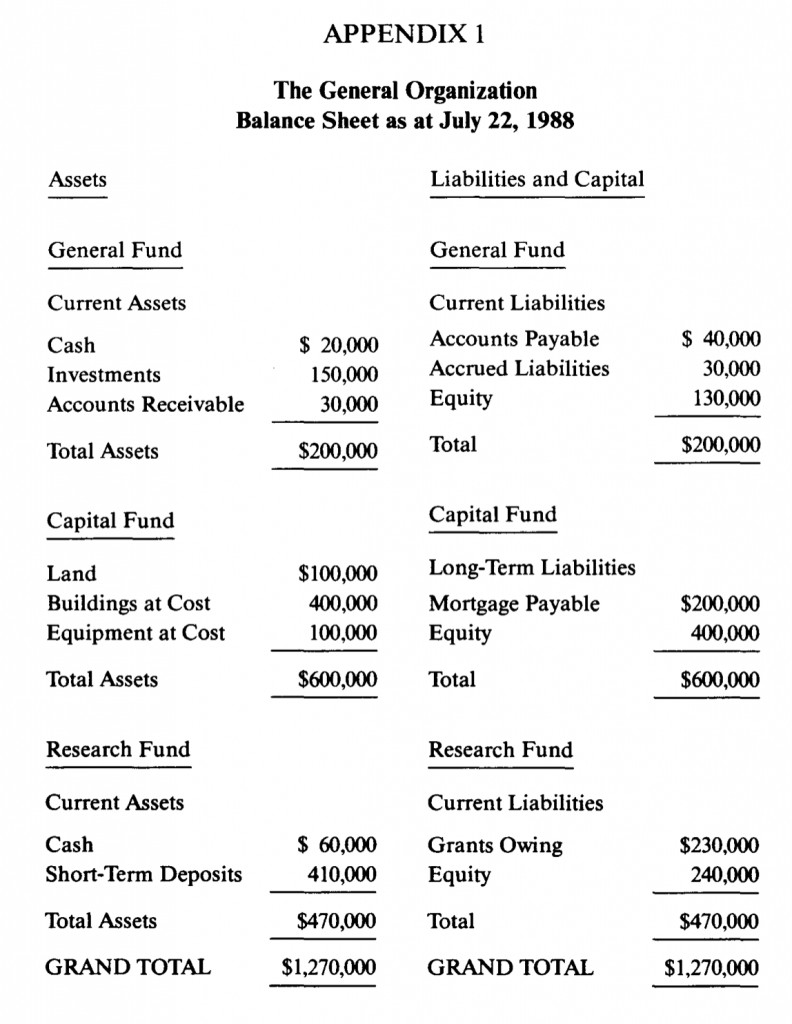

An indirect reference was made to fund accounting (item 1 on page 10) which

indicated the possibility of an organization having funds which it would account for separately. Some charitable organizations use fund accounting and prepare separate statements of revenue and expenses and, in fact, separate balance sheets for each fund.

Typically, an organization might first have a general fund. Revenue not destined for any special fund would be credited to this general fund and similarly the general fund would be charged with expenses not incurred on behalf of any special fund. The excess of income over expenditure (or the deficiency) on these general operations would be credited (or charged) to the accumulated surplus (or deficit) of the general fund.

The assets of this general fund would also be accounted for separately and, on the overall balance sheet of the organization, there would be a section on the asset side of the balance sheet showing those assets under the heading General Fund.

Similarly, the liabilities and surplus (deficit) of the general fund are kept separately as well and these will appear on the right-hand side of the overall balance sheet under the heading General Fund. The fundamental requirement of a balance sheet: assets = liabilities + equity, is then satisfied.

As well as the general fund, the organization could have other funds which it accounts for similarly. It may have a capital fund which holds its fixed assets: it may have a research fund holding funds destined for research: or it may have any number of other funds restricted to specified uses. An abbreviated balance sheet for an organization practising fund accounting appears in Appendix I. The overall balance sheet consists, in effect, of three separate balance sheets-one for each fund.

Parent and Grandparent Organizations

Many charitable organizations represent a local constituency but are related, in one way or another, to provincial or federal organizations dedicated to the same cause. They may be branches of a federal or provincial body and subject to its control over management and policies or they may be completely autonomous units with only a very loose association based on common interests.

It is important in financial analysis of a particular agency to be aware of the financial relations with any provincial or federal or other outside bodies.

An organization may appearveryweak financially. if it is judged simply on the hasis of its own income statement and balance sheet. On the other hand, it may have a parent organization with very substantial surpluses and reserves which is well able to provide funding. Conversely, an organization may have strong reserves and appear very well offbut its parent may be weak and faced with the need to deplete the assets of the branch to meets it own commitments.

Also in this area, the mechanics of transferring funds from the local branch to the national office should be explored if they are not readily apparent from the financial statements.

Notes to Financial Statements

As indicated previously, the notes to the financial statements form an integral part of those statements.

Usually, Note l or 2 to the financial statements outlines the significant accounting policies that are followed by the organization including such items as:

– revenue recognition (cash vs. accrual)

– the treatment of depreciation on fixed assets

– the method of recording investment income

– the basis of presenting combined or consolidated financial statements

– the treatment of certain expenses and revenue items both of which may be deferred under certain circumstances.

In addition, there is usually another note indicating the tax-exempt status of the charitable organization on the basis that it is a charitable organization that has been registered by the Minister of National Revenue.

Other items that may be covered by notes to the financial statements are as follows:

– significant restrictions on the expenditure of funds

– commitments or plans made for the expenditure of unexpended funds

– information regarding related-party transactions, if any.

Auditor’s Report

As indicated previously, the auditor’s report is an expression of an opinion about the financial statements. In some cases, the auditor’s report is a “‘clean opinion” and will state that the financial statements present fairly “‘the finan

cial position of the organization as at May, 198- and the results of its operations and the changes in its financial position for the year then ended in accordance with the accounting principles described in Note l to the financial statements applied on a basis consistent with that preceding year.” In some other situations, the auditor’s report may be qualified as a result of the inability of the auditors to satisfy themselves of the amount of donations shown on the financial statements from an audit perspective. Other reports may, in fact, indicate that the services of the auditor were not as auditor but rather an an accountant who prepared the statements based upon available information.

It should be noted that there are no generally accepted accounting principles for non-profit organizations; accordingly, the statement of policies to be followed is important. However, there are certain non-profit organizations such as hospitals or universities that are required to follow prescribed rules in accounting for the results of their operations for the year.

Conclusion

We have attempted to outline some general information and ideas as an introduction to the analysis of the financial information contained in audited financial statements of applicants seeking monies from a grantor in connection with an activity or project. Obviously, the sophistication of the financial information will vary from organization to organization.

SALLY FARR

Executive Director, The Trillium Foundation

LAURENCE C. MURRAY

Thorne Ernst & Whinney, Chartered Accountants