Summary: Celebrating its 11th anniversary, the collaborative approach to early childhood development in British Columbia implemented by United Way through its Success By 6 program is an intriguing model, which bears remarkable similarity to the Collective Impact framework. Supported by the provincial government and the credit union movement and coordinated by a modest provincial office, the Success By 6 BC Partnership is an example of a collaborative initiative led by United Way at the community level to address complex issues affecting children and families.

Introduction

Success By 6 B C—an initiative that strengthens Community services and provides support to young children and their families—is 11-years-old next month. This, in itself, is no small wonder.

Like a child whose remarkable development goes unremarked until she is all but grown, the innovative partnership in British Columbia of United Ways, the provincial government, the credit union movement, and Aboriginal and community leaders has matured into a province-wide vehicle for social change.

As such, the Success By 6 provincial partnership is a powerful demonstration of how United Way of the Lower Mainland (UWLM), as managing partner, is applying the conditions and practices of Collective Impact to improving early childhood development. Long before the Collective Impact concept gained the interest and momentum it has today, UWLM was setting up and supporting a provincial “backbone” office, linking and leveraging grassroots coalitions, recognizing the need for meaningful Aboriginal participation, and taking on the challenges of creating a common agenda and shared measurement.

This was neither by accident nor design. Rather, Collective Impact was (and is) a natural evolution of the United Way of the Lower Mainland’s long-standing approach as a catalyst and convenor for social change. In many ways, the very concept of Collective Impact is built right into the DNA of the United Way movement. And although a western construct, Collective Impact, as practised in British Columbia by Success By 6, has been complemented, shaped, and reinforced by the teachings and wisdom of Indigenous traditions.

Scholars will continue to study and refine the principles of Collective Impact. To this end, UWLM can offer some important lessons learned over the past decade. But first, a brief look back: What is Success By 6, how did it come about, and why does it matter?

A brief look back

Success By 6—a United Way-branded initiative conceived in 1989 in Minneapolis, Minnesota—was birthed in British Columbia from the unruly jumble of what is known as the Early Years sector. As elsewhere, the Early Years sector in BC is composed of a broad range of actors from government ministries and educational institutions, community agencies, and children’s advocates. While all play a role in supporting children and families, historically, none functioned as part of a formalized structure across the Early Years system (K. Adamson, personal communication, March 4, 2014).

The acknowledged risk—some would have described it as the reality—was fragmented early years planning, isolated or missing programs, duplicated services, and funding inequity within and between communities. More worrisome, children and families were potentially bearing the cost. Childhood vulnerability and poverty ratings in the province were climbing higher than anyone wanted or felt they needed to be.1 While all players knew that tackling these issues would (and does) require far more than a cohesive governance and operating structure, without it, the opportunity to have large-scale impact on a sustainable basis would remain elusive.

But there was more. The Early Years sector knew it could not just continue to talk to itself about these issues. There was an acknowledged need to include non-tradition—al partners, such as business and municipal leaders, in building community capacity. Furthermore, there was a very real challenge and need to engage Aboriginal communities in a way that was relevant and authentic to their experience. Not only was the harsh legacy of colonization and assimilation a significant barrier to establishing such trust and dialogue, but much of how community development was practised was not resonating with Indigenous teachings.

Into this environment, British Columbia’s version of Success By 6 baby-stepped. Launched in May 2003, it was and is governed by an Early Childhood Development Provincial Partnership composed of senior leadership from the BC government, United Ways, and Credit Unions of BC. In 2009, an Aboriginal partner joined the structure.

The vision then, as it is now, was to build the capacity of parents and communities so children could be healthy, safe, secure, socially engaged, and successful learners by the time they entered kindergarten. How would this be achieved? In true Collective Impact fashion, that would depend upon the community, its diverse needs, and its existing capacity, as each one was unique.

What Success By 6 looks like more than a decade later

Across 20 regions in British Columbia, Success By 6 supports the development of more than 100 Early Years Councils and Aboriginal Councils that work with over 550 communities. Each council brings together a cross-section of local stakeholders from multiple sectors to research community needs, develop strategic plans, identify priority areas for funding, and collaborate on delivering programs and activities for young children and their families.

Whether it is by holding local health fairs, developing Aboriginal language resources, hosting cultural events, creating resource directories, or planning new playgrounds, communities collectively decide what is required and take action to make it happen.

Pooled data and shared measurement have demonstrated the value of this approach. Province-wide evaluations carried out in 2009, 2011, 2012, and 2013 found increased community mobilization and coordination, and many examples of improved service delivery for families and young children.2

Equally impressive has been the strength and value of the funding relationship. Since the inception of Success By 6 and up until March 2013,3 the government of British Columbia has contributed $34.8 million. In this same period, government funding was leveraged by another $41.8 million brought in by United Ways, the credit unions, and community partners. In other words, a 120 percent return has been realized on the government’s decade of investment.

No longer baby-stepping, Success By 6 is achieving Collective Impact in stride. Here are some things we’ve learned along the way.

Lesson one: Choose your champions well

Despite their leadership in social change in British Columbia, the regional United Ways involved in Success By 6 could not have done this on their own. Not only would the dollars be beyond what could have been raised through annual campaigns but the very nature and timelines of Collective Impact—lengthy dialogue and fact-finding, independent decision-making, diverse tactics within common priorities, and long-term horizons to create change—can be challenging for individual donors to support.

Business and government funding is critical to sustainability, as the dollars used can be channelled to capacity-building outside the direct funding of programs and services. But equally important is the message embedded in cross-sector funding. For example, in the case of the credit unions, 25 cents per member per year has been contributed for the past six years for a total investment of $2.5 million. The impact of these dollars goes far beyond their immediate value. Like the tens of millions of dollars provided by the BC government, this community-based funding gives credibility to the Collective Impact approach.

Moreover, funders from multiple sectors can work together to address gaps. In the early phase of Success By 6, there was no dedicated funding stream for Aboriginal communities, and these communities received only .03 per cent of the $10 million disbursed to that point. Now that has changed completely with a dedicated Aboriginal Engagement granting stream, which has seen $1.05 million disbursed to Aboriginal communities every year since 2008.

Lesson two: Embrace diversity

Unique communities. Geographically-diverse regions. Multiple cultures. And a complex and painful history that began with European contact and still echoes the need for reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples to this day. One might well ask: How can you possibly build a common agenda from this?

We learned over time that it is possible if you begin with those whose lives and futures we all have a stake in—the children themselves. Nowhere did this prove truer than with efforts to engage Aboriginal communities in Success By 6.

Age-old, traditional Indigenous values and teachings believe that raising a child is everyone’s responsibility in the community. Acknowledging, listening, respecting, and valuing the wisdom of this belief was the basis of Success By 6’s ability to build a connection with Aboriginal leaders and elders. If we wanted the initiative to be relevant and authentic to Aboriginal families—whether First Nations on reserve, urban Aboriginals, or Métis—we had to look at the situation in new ways.

The deficit-based lens by which western society perceives Aboriginal communities, and in particular, the care of children, had to be turned on its head (M. Dawson, personal communication, March 6, 2014). Whether hurtful stereotype or researched statistic, the daunting list of challenges—family breakdown, youth graduation rates, poverty, and substance abuse—is well known to Indigenous peoples themselves. That’s why building capacity to support Aboriginal children and families must come from cultivating the many strengths found in cultural identity, self-respect, spiritual traditions, and belonging. It is this assets-based perspective that holds the key.

Success By 6 also had to make room and space for different meanings of community capacity building. Self-determination, self-government, the role of elders, and equity for Indigenous knowledge and processes—all these are critically important to the resilience of Aboriginal communities. This might run counter to capacity-building norms in non-Aboriginal rural and urban communities, but if the Collective Impact approach to Success By 6 is to succeed, we need to embrace a “Big Tent” approach and be responsive to cultural context and meaning.

Lesson three: Stick with it

Business imperatives change. Donor interests shift. Policy may ride on four-year election cycles. And economies rise and fall. Through all of this, Success By 6 BC has persevered– a testament to its partners, communities, and the energetic high of achieving significant milestones guided by a long-term vision.

A key tenet of Collective Impact is that you cannot micro-manage all the disparate strategies and tactics that arise in community after developing a common agenda and priorities. But savvy management recognizes opportunities to build momentum by sharing successes, transferring knowledge, and encouraging ideas that can be shown to advance required outcomes.

In British Columbia, many communities are at different levels in their ability to support children and families. Part of the role of the Success By 6 provincial office, managed by United Way of the Lower Mainland, is to identify and provide support to those communities that need it. This can range from sharing tools and plans from communities with strong capacity to developing culturally relevant resources that are more meaningful to those being engaged.

One example of this is the Granny and Grandpa Connections Box—inspired by the popular speech and language resource for Aboriginal children named “Moe the Mouse,”4 which primarily supports English language development. In collaboration with provincial Aboriginal partners, Success By 6 created an interactive resource that links culture and traditional languages to Aboriginal child development, a critical gap that the Connections Box now helps fulfill. Three years in development, the concept succeeded in attracting significant new funding so that 500 kits could eventually be distributed to First Nations communities, Métis organizations, and Aboriginal agencies in British Columbia.

Some would say that three years is a long time to develop a language and early learning resource. But there is power in bringing together many groups to tackle the complexity inherent in cultural diversity and different states of community capacity. This underlines that sustainability involves both patience and a willingness to not prescribe the outcome.

Lesson four: Use your “backbone” to leverage and link

In his most recent book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants (2013), author Malcolm Gladwell identifies several thought-provoking examples of how perceived disadvantages can often provide a veiled advantage. In other words, a David-like size may not be the problem we first assume when encountering Goliath-like challenges.

Size does matter, but it is not the sole issue in capacity building. While we doubt there are many days when the Success By 6 provincial office views its small size as a clandestine benefit in its quest to support children and families, it does lend urgency and focus (and boundaries) to its task. More remarkable yet is the impact achieved from leveraging and linking coalition knowledge and expertise.

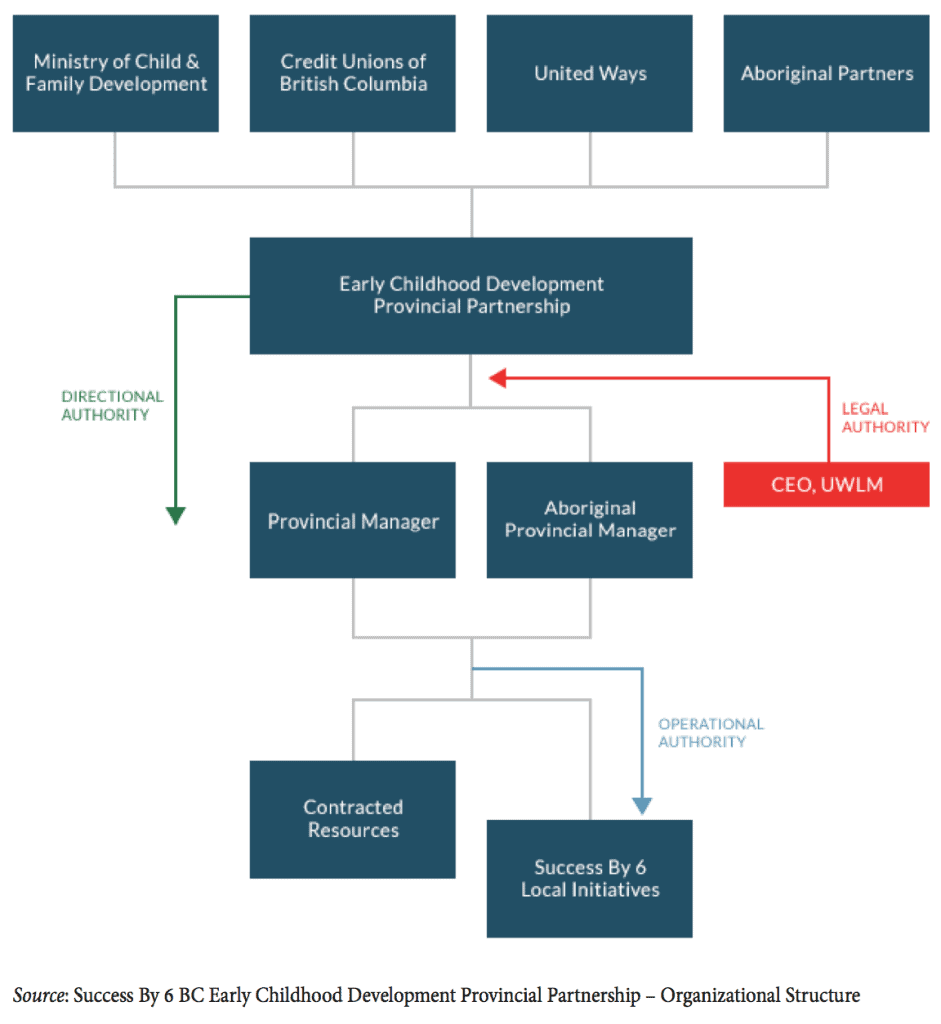

Staff numbers have varied over time at the provincial office, but it has always been very lean. Today, the office is composed of a provincial manager and an Aboriginal provincial manager—that’s it. Together, they have operational authority over all contracted resources and local Success By 6 initiatives in more than 500 communities. With direction from the Early Childhood Development Provincial Partnership and legal authority from United Way of the Lower Mainland, it is a tightly run initiative. One can’t help but be struck by the compact nature of the operation versus the reach of its influence.

As the “backbone organization” charged with supporting and driving social change across broad and diverse networks, the Success By 6 provincial office plays a crucial role. Continual dialogue among local networks is key. As is the need to be nimble when responding to issues, innovative when it comes to stretching funding, and hyper-aware of what is happening in communities.

Building grassroots coalitions to advocate for and support young children and families depends upon strong relationships and clear communications. We’ve learned first-hand that this occurs best when it is modelled and continually strengthened within the funding partnership and the provincial office.

Lesson five: As hard as it is, measure and evaluate

Early childhood development in British Columbia is governed by a vision that “children are healthy and develop to their full potential.” This vision is guided, in turn, by four long-term outcomes:

• Mothers are healthy and give birth to healthy infants who remain healthy.

• Children experience healthy early child development, including optimal early learning and care.

• Parents are empowered to nurture and care for their children.

• Communities support the development of all children and families.

There is nothing easy about measuring any of these outcomes, never mind creating an integrated evaluation and reporting system province-wide. But important progress has been made. Thanks to funding from The Max Bell Foundation and the Government of British Columbia, logic models and shared measurement tools have been developed for outcomes three and four. Success By 6 has taken the lead on administering the capacity building evaluation, while the Ministry of Children and Family Development is the lead on parent education and support evaluation.5

Shared measurement—a key condition of Collective Impact—can reduce duplication, identify ways to improve programs, and roll up data points for provincial and regional reporting. But even here, we have learned of the need to be flexible in order to be responsive and relevant. For example, initially, Aboriginal communities did not participate in the evaluation related to community capacity. When participation became mandatory, a culturally appropriate means beyond quantitative surveys had to be found.

A Photovoice approach, which uses dialogue and video and/or photos to capture the environment and share experiences and critical reflection—provided a successful alternative. Building on traditions of storytelling common to oral societies, evaluation practices gained from increased engagement of Aboriginal communities, while also incorporating Indigenous approaches to accountability.

Promoting policy and systems change

A key tenet of Collective Impact is to recognize that isolated initiatives can struggle to deliver higher-level systems change. Even if good outcomes occur, challenging questions arise about sustainability and scalability. How long will the intervention stick? Can the results be replicated? What happens when funders move on?

In contrast, Collective Impact involves many stakeholders working together through multiple channels. Integrating, coordinating, and leveraging different kinds of expertise can build a less isolated and more networked approach to problem solving and innovation. This not only drives change at the community level but can also drive change in government as well. At its best, Collective Impact can provide government with more policy tools and funding levers to apply to social issues.

Here’s one example. This spring, the BC Ministry of Children and Family Development is soliciting proposals for test sites for Community Early Years Centres. These centres will build on community services already in place that foster the health, well-being, and development of children. Their focus is on increasing coordination and integration, collaborating across programs and services, and reducing barriers that inhibit access for families with young children.

In the past, similar calls for proposals would have allowed multiple organizations within a community to compete for early years funding. Not so this time. Embedded within the Ministry’s criteria is the need for each proposal to be endorsed by a community Early Years Table. Furthermore, only one proposal per table will be accepted for consideration. We believe this shift acknowledges the collaborative and systematic approach used by Success By 6 and our partners. It is causing organizations and communities to rethink how early years services are delivered in British Columbia.

At the municipal level, policy changes are just as evident. While each situation depends on local context, the influence of the community Early Years Tables are at work. For example, in one community, the city council endorsed a Community Children’s Charter. It is now woven throughout the municipal social development strategy. In another town, zoning by-laws were amended to reflect local childcare needs. A third community waived late fees on children’s library cards. A fourth is including plans from the Early Years Table in an Integrated Community Sustainability Planning process. Yet another community is enhancing transit for families with young children and including children’s voices in municipal planning.

Systems change is also moving beyond public policy to encompass other stakeholders, such as business. We know of a Chamber of Commerce that has created a Family- Friendly Business Award. This same chamber also intends to promote a family-friendly business policy, with self-evaluation kits for businesses. While we still have a long way to go, we can see that changes in policy, attitudes, and systems are already happening as the direct result of Collective Impact approaches and experience.

Where to next?

Reaching the 11-year mark is an exciting milestone in the life of Success By 6 BC. We are in our second decade, we have grown up with Collective Impact, and—as managing partner—United Way of the Lower Mainland remains committed to evolving this approach to social change. Two other initiatives we are pursuing, one involving placebased strategies in neighbourhoods in the Lower Mainland and the other encompassing non-medical home support to seniors throughout British Columbia, include important elements of the same Collective Impact concept. We expect more learning to come from these future activities.

In the meantime, we are proud of the results that Success By 6 has achieved in its first decade. Aboriginal leaders and communities—on reserve, urban, and Métis—are a crucial part of this initiative, and we have learned much through their engagement. Community business and municipal politicians are aware, involved, and have become some of our strongest advocates for sustainable funding. The Early Years sector is working more closely together, and the coalitions are a deep source of local knowledge and expertise.

In the future, these networks hold promise for a streamlined, effective, and efficient way of making funding decisions and sharing information on the needs and opportunities for children and families—even beyond Success By 6. Collective Impact is a big part of this potential and vision. The lessons we’ve learned about champions and diversity, about patience and commitment, and about leveraging and measuring were captured through more than a decade of front-line experience and collaboration that reflects a Collective Impact approach.

Like childhood, the time has passed quickly.

Notes

1. According to the Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP) at the University of British Columbia, a child vulnerability level above 10 per cent is preventable. B.C.’s child vulnerability rate is about 30 percent based on HELP’s latest research: http:// earlylearning.ubc.ca/ .

2. See http://www.successby6bc.ca/ecd-evaluation/evaluation-tools-project-reports .

3. Fiscal 13/14 figures were not available as of the date of writing.

4. Moe the Mouse® Speech and Language Development Program—A Program of the BC Aboriginal Child Care Society: http://www.acc-society.bc.ca/files_2/moe-themouse.php .

5. For an overview of Success By 6 BC progress, see http://www.successby6bc.ca/sites/default/files/Quick%20Guide%20to%20Progress%20of%20the%20BC%20ECD%20Evaluation%20Project.pdf .

Reference

Gladwell, Malcolm. (2013) David and Goliath: Underdogs, misfits, and the art of battling giants. Little, Brown and Company. URL: http://gladwell.com/david-and-goliath/ [April 1, 2014].

Michael McKnight is President & CEO of the United Way of the Lower Mainland and has more than 25 years of experience in building community Email: michaelm@uwlm.ca .

Deborah Irvine is a former chief operating officer with United Way of the Lower Mainland and currently consults on non-profit and organizational strategy. Email: deborah1irvine@gmail.com .