The fiscal policy of the Canadian government has, since the inception of modern tax, encouraged charitable endeavours by providing for a deduction to persons who make contributions to charitable institutions and by providing for an exemption from income tax for the income derived by charitable institutions.1 This paper will focus on the income tax treatment of charitable institutions, the nature of the exemption and the requirements which must be met for the exemption to be maintained.

The Income War Tax Act 2 in 1917, provided quite simply that “the income of any religious, charitable, agricultural and educational institution, board of trade and chamber of commerce”3 was not liable to taxation. During the intervening years numerous amendments were passed designed to plug loopholes, differentiate between various types of charitable endeavours and to achieve certain policy objectives. The result is that today we have a detailed and complex set of rules which restrict and regulate the exemption.4

In general terms a charitable institution must fit into one of three categories to qualify for the exemption:

( 1) an organization, whether or not incorporated, which devotes all of its resources to charitable activities carried on by it;5

(2) a corporation, constituted exclusively for charitable purposes, which expends its funds on charitable activities carried on by it or acts as a foundation and distributes funds to other charitable organizations;”

(3) a trust holding all of its property exclusively for charitable purposes which carries on charitable activities or acts as foundation to distribute funds to other charitable organizations.7

The detailed conditions which apply to each of the above categories will be discussed below, but, from the brief description, it is apparent that the denominator which is common to all of the categories is the reference to “charitable activities” and “charitable purposes”. However, the Income Tax Act does not contain a definition of the word “charitable” nor of the phrases “charitable activities” or “charitable purposes”. The question of whether a particular object or activity is charitable will be determined by certain criteria originally established in the leading case of Pemsel v. Special Commissioners of Income Tax. Charitable purposes and activities are limited to the following:

(I) the relief of poverty,

(2) the advancement of religion,

(3) the advancement of education, or

(4) other purposes of a charitable nature beneficial to the community as a whole.

The Department of National Revenue has issued an information circular9 which indicates, to an extent, government policy in applying the above criteria. From the information circular and from the case law the following points should be noted:

I. The relief of poverty means the assistance of persons who have not the means to satisfy the necessities of life. The Department has indicated that organizations for the relief of poverty include national or local organizations such as a Children’s Aid Society, an orphanage, a family welfare bureau and an organization supplying low cost housing to the poor.

2. The advancement of religion includes the dissemination and futherance of religious knomwledge, acts and orders. Oganizations which would qualify would include a house of worship such as a church, synagogue, temple, a religious library, an order of monks, etc. The term “religious” is not limited to the Christian religion although it has been suggested that an organization which teaches a religion whose moral concepts are opposed to Christianity would be denied the exemption.10

3. Organizations whose purpose is the advancement of education include schools, universities, libraries, museums, etc., not operated for private gain or profit. However, the Department takes the position that socities for the dissemination of information on a particular subject or for the promotion of self-education will not qualify. It has been held that the Audubon Society of Canada is not a charitable organization even though it promotes an increased knowledge of birds. 11 Education would also include the dissemination of a philosophy or system of doctrine provided that it is not pernicous or subversive of morality, but not the advocacy of any political party.

4. The category of purposes beneficial to the community as a whole is the most difficult to interpret. It includes purposes whose benefits are available to all members of the community and may not be confined to members of a family, employees of a company or any similar restrictive grouping. The purpose can be the provision of public recreation but not the advancement of any particular sport. A social or cultural facility such as a community hall for the benefit of the community would qualify.

The first exemption noted above relates to a “charitable organization”.12

In order to qualify as a charitable organization, the following requirements must be satisfied:

(I) The charitable organization may take any form. It may but need not be incorporated or it may but need not be a trust.

(2) All of its resources must be devoted to charitable activities carried on by the organization itself. If any part of the funds of the organization are distributed to other institutions or organizations which carry on charitable activities, the distributing organization will not qualify for an exemption under this particular provision. In addition, this requirement would appear to technically prohibit the organization from carrying on any business activity since some of its resources would thereby be deviated from its charitable activities. However, there is administrative latitude in this respect, as a policy matter, and many charitable organizations do carry on business activity of some type for the purpose of raising funds for their charitable purpose.

(3) No part of the income of the organization may be payable to, or otherwise available for the personal benefit of, any proprietor, member or shareholder. Thus, a corporation whose purposes and objects were of a charitable nature was held not to be “charitable organization” because a substantial part of its income was being used for the benefit of the President and his family. 13 In a second case a religious organization was denied an exemption as a charitable organization because a part of the income of the corporation was under the sole control of one individual and appeared to be available to a “proprietor, member or shareholder”.14

A corporation or trust which does not devote all of its resources to charitable activities carried on by itself will not qualify under the foregoing provision. Nevertheless such a corporation or trust will be exempt from income tax if it qualifies as a “non-profit corporation”15 or as a “charitable trust” 1 the second and third categories of exemption noted above. The thrust of the conditions which must be satisfied is the same for a non-profit corporation and a charitable trust although there are some important differences which will be noted below. In order to qualify for the exemption the following requirements must be met:

(a) The non-profit corporation must be constituted exclusively for charitable purposes. All of the property of a charitable trust must be held absolutely in trust exclusively for charitable purposes. If any of the purposes for which the corporation is constituted or for which the trust property is held, are not “charitable”, the “exclusively charitable” test will not be satisfied. Lawrence J. stated in an English case “it is not enough that the purposes in the memorandum should include charitable purposes; the memorandum must be confined to those purposes…”17 • Thus, care must be taken in drafting the objects of the coporation or the terms of the trust instrument, so that no purposes which are not charitable will be included;

(b) No part of the income of the corporation may be payable to or otherwise available for the personal benefit of any proprietor, member, or shareholder;

(c) Since June I, 1950, it may not have acquired control of a corporation.

Control is acquired if the non-profit corporation or charitable trust, either alone or together with persons with whom the corporation of the trust does not deal at arm’s length, hold more than 50% of the issued share capital of the corporation (having full voting rights under all circumstances). Control will not be deemed to have been acquired if the corporation or trust nas not purchased (or otherwise acquired for consideration) any of the shares of that other corporation. Thus, if a non-profit corporation or charitable trust owns more than 50% of the issued voting shares of another corporation but all such shares were acquired by bequest or donation, control will not be deemed to have been acquired and the corporation or trust will still qualify for the exemption. However, if the corporation has acquired any shares, even one share, by purchase and together with persons with whom it does not deal at arm’s length it holds 50% or more, it will be deemed to have acquired control and it will not qualify for the exemption. There is a further tax penalty where control of a corporation is acquired by a non-profit corporation or charitable trust in circumstances causing the corporation or trust to lose its exemption. The controlled corporation will be required to pay a special tax of 33/J% of all dividends paid to the controlling corporation or trust to the extent that such dividends are paid out of designated surplus.19

(d) The corporation or trust must not carry on any business. It should be noted that a charitable organization under Section 149(1)(f) is not specifically restricted from carrying on any business. The prohibition is not merely against the carrying on of an “active business” but any business. The corporation or trust should ensure that its activities do not consitute a business even of a passive nature, but rather that its income be derived solely from investments.20 In this connection it should be noted that although an “adventure in the nature of trade” falls within the definition of business, it has been held that an isolated adventure in the nature of trade is not sufficient by itself to characterize the activities of the person participating in such adventure as necessarily “carrying on” a business.

(e) The corporation or trust must not have incurred any debts since June 1, ‘1950 other than obligations arising in respect of salaries, rents and other current operating expenses. This is an absolute prohibition against borrowing for any purpose other than those specified. The acquisition of property on an instalment basis and the granting of a mortgage on the acquisition of property fall within the prohibition. Note that a “charitable organization” is not prohibited in this respect and may incur debts.

(f) The corporation or trust must expend not less than 90% of its income each year (subject to rules discussed below) as follows:

(i) in charitable activities carried on by the corporation or trust itself;

(ii) as gift to a tax exempt “charitable organization” iin Canada; (iii) as gifts to another tax exempt non-profit corporation resident in Canada. Note that both the non-profit corporation and the charitable trust may make gifts to another non-profit corporation but that neither may make gifts to another charitable trust.

(iv) A non-profit corporation may make a gift to Her Majesty in Right of Canada or a province or to a Canadian municipality but a charitable trust may not make such gifts for the purposes of satisfying the 90% distribution rule.

The requirement that the non-profit corporation and charitable trust distribute not less than 90% of their income each year is extremly harsh in some respects. The corporation or trust is effectively prevented form establishing a reasonable reserve but, perhaps more important, the distribution each year would have to be based on an estimate of that year’s income because the actual income would not be known until the year end or later. Thus, hasty last minute distributions would result and the prudent director or trustee would want to distribute more than 90% of the estimated income because of the dire consequences which would follow if the actual income was in excess of the estimate and insufficient distribution had been made.

In order to alleviate these burdens to some extent the Act contains two provisions giving the corporation or trust some flexibility in connection with the 90% distribution rule.

(I) The corporation or trust need not distribute or use any of its income in its first taxation year after incorporation or creation. It may elect that all or any part of the amount spent in its’secorid year, applies to the income of the fiscal year.22 Thus the first use and distribution of income may be deferred one year.

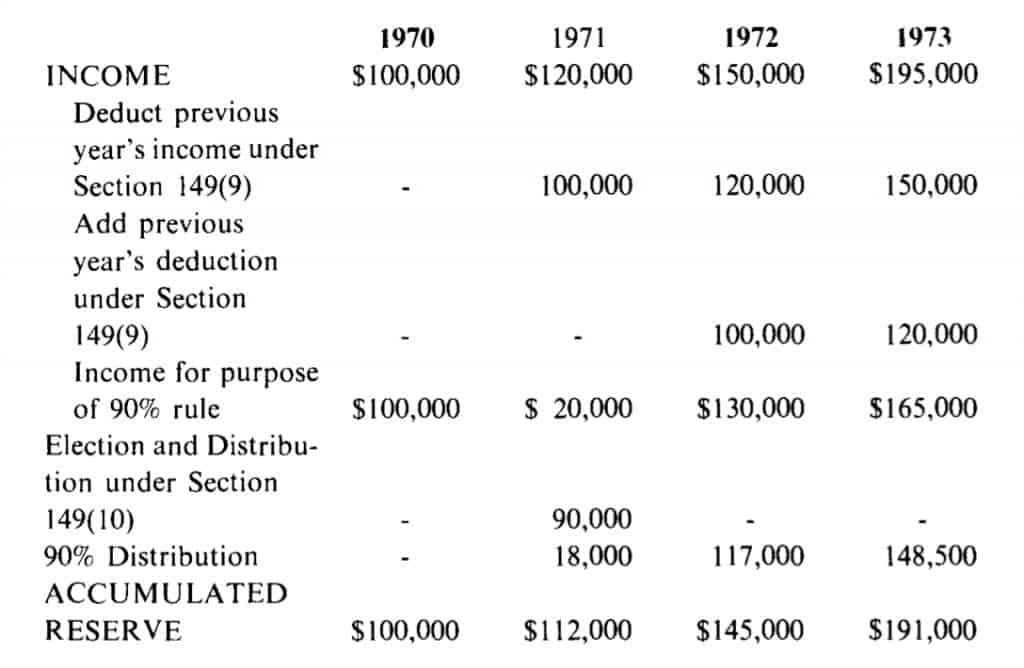

(2) In computing its income for the 90% rule, the corporation or trust may deduct, as a reserve, the actual income for the previous year. It must then include in income the reserve which it deducted the previous year. 23 This procedure will enable the corporation or trust to build up a reserve of funds out of income equal to the previous year’s income plus the 10% not distributed from all other years.

The following example illustrates the rules described above and the distribution required by a corporation or trust to retain its tax exempt status.

I. In computing its income, the corporation or trust will be entitled to deduct expenses incurred in earning the income, but will not be able to deduct costs of any charitable activities carried on by it. Thus, part of the expenditures for rent, salaries, printing and mailing receipts, bookkeeping expenses, etc., will be deductible. It is unlikely that there would by any interest expense because of the basic prohibition against borrowing. If the corporation or trust owns depreciable property from which it derives income, there is nothing to prohibit the corporation or trust from deducting capital cost allowance in respect of such property in computing its income. Of course on the sale of the property, if any recapture arises, the amount of recapture would be included in income and would increase the required amount of distribution without a corresponding increase in the cash flow. Accordingly, it is probably relatively unusual for the corporation or trust to claim capital cost allowance.The income of the non-profit corporation or charitable trust for the purposes of the 90% rule will be determined in the same manner (subject to certain exceptions which will be discussed below) as if the corporation or trust were a taxable entity. There are a number of important considerations which should be noted in connection with this provision.

2. The corporation will have to include in computing its income all dividends received from other corporations. In computing taxable income, a corporation is entitled to deduct dividends received from a taxable Canadian corporation or another corporation resident in Canada and controlled by it, but these dividends are initially included in computing income.24 Since the 90% rule is based on income rather than taxable income, all dividends must be included.

3. A trust is treated basically as if it were an individual.25 This leads to a problem with respect to dividends received by the trust. Where a taxpayer is an individual (including a trust), in computing its income it must include the full amount of all taxable dividends received from corporations resident in Canada plus one-third of such dividends. 26 If the trust receives a dividend of $90.00 it will be required to include $120.00 in its income. If the trust is a taxable entity, in computing its tax it would reveive a credit in respect of the dividend received; however the charitable trust which is tax exempt does not use the credit. In order to satisfy the 90% rule, technically, the charitable trust would be required to distribute $108.00 in respect of the receipt of a dividend of

$90.00. Obviously it was not the intent of the legislature to require the trust to distribute more income than it had actually received and an amendment to the legislation is called for in this respect.

4. In computing the income of a trust generally, there may be deducted amounts paid or payable in the year to beneficiaries,27 in computing the income of a charitable trust for the purpose of the 90% rule, no deduction is available for amounts paid or payable by the trust to beneficiaries.28

5. Taxable capital gains realized by the corporation or trust are excluded in computing its income for the purpose of the 90% rule.29 No distribution is required in respect of capital gains. One-half of all capital losses (“allowable capital losses”) will be deductible by the corporation or trust in computing their income and will reduce the required distribution in order to maintain the exemption.

6. A trust is deemed to have disposed of all capital property owned by it on the later of January I, 1993 or 21 years after the date on which the trust was created and thereafter every 21 years.30 The trust will be deemed to have received fair market value for non-depreciable capital property and the average of fair market value and undepreciated capital cost for depreciable property. This deemed disposition may give rise to capital gains, capital losses and/ or recapture. As noted above, taxable capital gains are excluded in computing the income of the trust for the purpose of the 90% rule. It is unlikely that recapture will arise primarily because capital cost allowance is rarely taken. However, the existence of an allowable capital loss as a result of the deemed disposition will reduce the income and the required distribution for that year.

7. In computing the income of a corporation or trust for the purpose of the 90% rule all g1jts received by the corporation or trust must be included other than the following:31

(i) A gift received subject to a trust or direction that the property given, or property substituted therefor, is to be held permanently by the corporation or trust for the purpose of gaining or producing income therefrom. In the opinion of the Department of National Revenue the word “permanently” must be given its ordinary meaning of

“forever”. Thus, if a trust instrument contained a requirement that the trust be wound up within a stipulated period of time, all gifts made to that trust would be included in its income for the 90% rule, since they could not be held “permanently” by the trust. The Department has also indicated that the trust or direction that the property be so held must be made or imposed by the donor. Accordingly, a provision in the Letters Patent or trust instrument directing that all gifts received by the corporation or trust are to be held permanently for the purpose of gaining or producing income therefrom would not be sufficient.

(ii) A gift or a portion of a gift in respect of which it is established that the

donor has not been allowed a deduction in computing his taxable income. The deduction for charitable donations applies only with respect to donations to “registered” charitable organizations. If the non-profit corporation or charitable trust is not registered, a donor will not be entitled to a deduction in respect of a gift and accordingly all such gifts will be excluded from the computation of income of the corporation or trust for the purpose of the 90% rule. Consider the situation of a corporation or trust which is registered and receives gifts which are not subject to a trust or direction that they be held permanently to produce income. If the donor deducts the full amount of the donation in computing his taxable income, the corporation or trust will be required to include the full amount of the gift in its income for the 90% rule. If the donor deducts only a part of the gift, either because he has reached his 20% limit or because he does not choose to take the deduction that is available, only that part which is in fact deducted by the donor must be included in computing the income of the corporation or trust. The balance of the gift is excluded from the income of the corporation or trust. If the donor receives no deduction in respect of the gift, the entire amount of the donation will be excluded from the income of the corporation or trust. Under the old Act there was some uncertainty as to whether this provision applied to inter vivos gifts only or whether it applied as well to testamentary gifts. If the provision applied to testamentary gifts, no part of such gift would be required to be distributed since the deceased donor would not have obtained a deduction in respect of the gift and the gift would therefore, have been excluded from the income of the recipient. This was in fact the manner in which the provision was administered by the Department. Some concern was expressed that on a proper interpretation of the section, the exception must be related in some way to the deduction available to a donor for charitable donations, i.e., the donor had to be a person capable of being a donor within the ambit of the sections providing for deductions for charitable donations. Since a deceased taxpayer could never fall within the ambit and qualify for a deduction in respect of his testamentary gift, such a gift could never fall within the exemption provided by this paragraph. In order for a testamentary gift to be excluded from the income of the receipient corporation or trust it would have to be received subject to a trust or direction that the property was to be held permanently by the corporation or trust for the purpose of producing income. This dilemma has been solved by the recent amendments to the new Act.32

Where a taxpayer who dies after 1971 makes a testamentary gift to a registered Canadian charitable organization, the gift is deemed to have been made by the taxpayer in the year in which he died. Thus the testamentary gift could qualify as a deduction in computing the taxable income of the taxpayer for the year of his death. The balance, if any, of the testamentary gift (that part which is not deducted by the deceased) will be excluded in computing the income of the recipient non-profit corporation or charitable trust. The part of the testamentary gift which is deducted in computing the taxable income of the deceased taxpayer may also be excluded in computing the income of the non-profit corporation or charitable trust if the gift imposes a trust or direction that the property be held permanently to produce income.

(iii) A gift made by a person who was not taxable under Section 2 for the taxation year in which the gift was made. This will include gifts by persons resident in Canada who have no taxable income for a particular year. It will also include gifts by non-residents who have no taxable income earned in Canada for the year. It would also appear to cover gifts received by a non-profit corporation or charitable trust from another tax exempt organization. If one non-profit corporation makes a donation to a second non-profit corporation, that donation would qualify as part of the required distribution by the first nonprofit corporation but would not be included in computing the income of the recipient non-profit corporation for the purposes of its 90% rule. It would appear that the use of two tandem non-profit corporations could defeat the requirements and intent of the 90% distribution rule and would permit the building up of larger reserves out of income than would otherwise be avialable.

In summary, a donor may make a gift to a non-profit corporation or charitable trust and direct how and when the gift may be used without causing the gift to be viewed as income of the corporation or trust (for the purpose of the 90% distribution rule) as long as the donor did not deduct the gift as a charitable donation in computing his taxable income. If the donor made a deduction in respect of a part of the gift, then only that part of the gift in excess of the amount deducted can be received by the corporation or trust without complication. To the extent that the donor has obtained a deduction and thereby received a benefit as a result of his donation, the gift (or the part deducted) must either be substantially expended currently by the corporation or trust in satisfaction of the 90% rule, or it must be maintained permanently as part of the capital of the corporation or trust to generate income.

Footnotes

I. The term “charitable institutions” is used in this paper in the broadest sense to include charitable corporations, trusts and other unincorporated charitable organizations carrying on charitable activities on their own or, as foundations, funding charitable activities carried on by others.

2. Statutes of Canada, 1917, Chapter 28

3. Section 4(c) of the Income War Tax Act

4. Section 149

5. Section 149(1) (f)

6. Section 149(1) (g)

7. Section 149(1) (h)

8. 3 TC 53

9. Information Circular No. 73-11 dated May 14, 1973. This circular establishes guidelines for organizations wishing to obtain registration as registered charitable organizations. A charitable organization does not need to be registered to be exempt from income tax but requires registration to be eligible to issue receipts for donations for deduction purposes. Nevertheless the circular does set out a policy with respect to the application of the exemption provisions.

10. See H.A.W. Plaxton “Canadian Income Tax Law” (the Carswell

Comapny Limited, 1939) at page 71.

II. Hobson v. M.N.R. (T.A.B.) 59 DTC 211

12. Section 149(1) (f)

13. Christian Homes for Children v. M.N.R. (T.A.B.) 66 DTC 736

14. Mikkel Dahl, Inc. v. M.N.R. (T.A.B.) 68 DTC 743

15. Section 149(1) (g)

16. Section 149(1) (h)

17. Karen v. CIR (1932) 17 T.C. 27

18. Section 149(7) (a)

19. Section 194

20. Interpretation Bulletins IT-72 and IT-73

21. Tara Exploration and Development Company Limited v. M.N.R. (S. Ct)

71 DTC 6288 confirming (Exch. Ct) 70 DTC 370. This particular point is discussed only in the Exchequer Court decision.

22. Section 149(10)

23. Section 149(9)

24. Section 112( I)

25. Section 104(2)

26. Section 82( I)

27. Section 104(6) and (12)

28. Section 149(7) (c)

29. Section 149(2)

30. Section 104(4) (b)

31. Section 149(7) (b)

32. Section 110 (2.1)