We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to make significant systemic change toward eradicating gender-based violence for good, writes Be the Peace Institute’s Sue Bookchin, on the first anniversary of the release of the Turning the Tide Together report.

In recent decades, the murder of 14 female engineering (and one nursing) students at Montreal’s École Polytechnique in 1989 was the defining mass shooting in Canada many of us could remember. Every year since then, this event is marked by 16 days of activism culminating on December 6, the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women. The shooter was a fellow student who blamed his female peers for his struggles. But it took some time before there was public acknowledgement of the misogynistic nature of this violence, even though he openly declared he was “fighting feminism.”

Thirty-one years later, Nova Scotia is home to the worst mass shooting in Canadian history. On the evening of April 18, 2020, beginning in the rural community of Portapique and moving to 16 other locations, 22 people were killed. Many more were injured and traumatized in the 13 hours before the shooter was shot by an RCMP officer in the community of Enfield.

For those of us working in the field of gender-based violence (GBV), it was evident from media reports early on that the perpetrator’s serial abuse of his long-time intimate partner was a critical indicator in the context of this tragedy.

The Mass Casualty Commission inquiry

The joint federal-provincial inquiry into the causes and contexts of the mass casualty commenced in October 2021. Be the Peace Institute (BTPI) applied for and was designated participant status in the proceedings. BTPI is a small non-profit dedicated to promoting gender intersectional equity and justice by addressing the systemic roots and consequences of GBV. GBV is an umbrella term that encompasses intimate partner, family, sexualized, and other forms of violence committed based on gender identity or expression.[1] Our aim was to ensure that the context of GBV was brought into the proceedings as a significant dimension of the casualty and the subsequent public safety failures. Fortunately, colleagues in eight other organizations in the women-serving sector joined in that collective aim. Having never participated in an inquiry of this nature, we were fortunate to have Shawna Paris-Hoyte from Dalhousie Legal Aid as legal counsel, accompanied by their cadre of law and forensic social work students.

In the proceedings

As the inquiry commenced, the Mass Casualty Commission team described the tragedy as beginning with the first person who was killed. They initially overlooked the significance of the perpetrator’s violence toward and attempted murder of his intimate partner that preceded the unfolding horrors.

Central to the proceedings for many months was the focus on policing structures and responses and the inconsolable grief and anger of the victims’ family members at the failure to save their lives. Rightfully so. Eventually, the context of the perpetrator’s long history of violence toward others, the multigenerational violence in his family of origin, and the coercive controlling abuse and terror he inflicted on his intimate partner for the better part of 20 years was unearthed.

The expert roundtables of researchers, scholars, and experts in the field of GBV comprise a master class on the topic for anyone who wants to fully understand the dimensions and nuances of GBV (see proceedings/recordings from mid- to late July 2022). These and the commissioned reports – including one from the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre, which provides supports and services to people affected by sexualized violence, detailing the longtime sexual exploitation of vulnerable Black and Indigenous women in the community – provide evidence of the inextricable link between GBV, misogynistic ideologies of oppression, and mass killings. Gender-based violences have impacts that reverberate throughout our communities, and on a national and global scale.

It was imperative that the commission understand that complex family and intimate partner violences are a root cause of this tragedy, even though the perpetrator’s victims were not all women.

Still, we had no idea whether we, in a coalition with the Transition House Association of Nova Scotia and Women’s Shelters Canada, as well as the other women-serving organizations, would be given opportunity to directly address the commissioners. It was imperative to us that the commission understand that complex family and intimate partner violences are a root cause of this tragedy, even though the perpetrator’s victims were not all women.

When GBV persists unabated and without skilled intervention, it can become a public safety issue far beyond the confines of a private family matter. In this case, the perpetrator, his family, his victims, and his intimate partner were failed by every institution with designated responsibility to protect children, women, and vulnerable others. It is possible that intervention at various junctures over the years may have prevented such massive loss of life in those 13 hours in April 2020.

We brought passion born of decades of burden on the shoulders of women’s organizations to prove that GBV is an issue worthy of priority attention and resources.

It was not until the last day of August 2022, less than a month before the inquiry ended, that we and other women’s advocates finally had opportunity to address the commissioners directly. Collectively we brought local knowledge, survivor experiences entrusted to us, gendered analysis, and root-cause historical context. It is the systemic patterns of patriarchy and the supremacy of white male privilege embedded in our institutions and our social milieu that enabled the perpetrator to escape detection, justice, and accountability, even though many people knew of his exploits. We also brought passion born of decades of burden on the shoulders of women’s organizations to prove that GBV is an issue worthy of priority attention and resources.

Turning the Tide Together report is launched

It has been almost a year since the Mass Casualty Commission released its final report, Turning the Tide Together – seven volumes and 130 detailed recommendations addressing every aspect of the commissioners’ work – to a packed room at a hotel in Truro, Nova Scotia. In attendance on March 30, 2023, were Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston, and government officials, along with family members of those killed; inquiry participants; a plethora of media; representatives from policing, public safety, justice, health, academia, the community sector; and interested citizens.

Michael MacDonald, the chief commissioner and sole male among the three, presented violence/GBV as one of the three pillars of the report’s findings. As we listened and took in the words that were being spoken, there was a surreal moment when I turned to our legal counsel in amazement, saying, “Wow – they actually heard us!” It was one of those rare moments in the women’s sector, when you hear your own words reflected back to you, affirming what you have contributed as valid and essential intelligence. For those of us in this sector who waited and watched and strategically formulated the perspective and analysis only we could bring from a community-based vantage point, it was a profound moment of recognition. And for that to be documented in such a public and authoritative forum was revelatory.

Are there still some things missing? Yes, of course. But I am left with irrefutable verification that misogyny and GBV are serious human rights violations and public safety threats. This is no longer up for debate. Perhaps we can finally liberate victim-survivors of GBV and organizations that support and serve them from the demand to constantly prove that GBV has long-term and widespread harmful impacts. Maybe there will be more allies to not only shoulder the imperative for improved services after violence, but also to facilitate the systemic change that will eradicate it.

What now?

In Turning the Tide Together, the commission team was eloquent in their conclusion that “failures to protect women [and gender diverse people] from gender-based violence cannot be attributed to lack of knowledge.” They acknowledge GBV as an epidemic in Canada and deemed a global pandemic by the United Nations. It is ubiquitous and “has been consistently present throughout societies to the point that it is seen by many as routine or normal.” Further, its “prevalence is the result of inadequate and uncoordinated actions by individuals and organizations, coupled with insufficient attention to structural and institutional barriers that block progress.”

The Turning the Tide Together report recommends funding for the community-based GBV advocacy and support sector ‘commensurate with the scale of the problem.’

The report goes on to talk about lifting women and girls out of poverty, mobilizing a whole-of-society response, emphasizing primary prevention and supporting healthy masculinity. It affirms the need to reference historical patterns of violence against Indigenous and Black Nova Scotian people and address the needs of those most marginalized. And, importantly, it recommends funding for the community-based GBV advocacy and support sector “commensurate with the scale of the problem.” It suggests that these are front-line public services that should be funded not as discretionary services but as essential agents in preventing violence in our communities; that they complement government-run programs, fill essential service gaps, and even address harms from government/state-run programs felt by survivors of GBV and should be valued as such. “Simply stated: our collective and systemic failures are attributable to the fact that we underfund women’s safety.”

For decades, we have been having some of the same conversations about gendered violence, gender equity, and all related and persistent forms of oppression. While the conversations evolve as our understanding of trauma, neurobiology, and social movements grows, we have not appreciably moved the needle on the prevalence of GBV in our society. Perhaps this is testament to the possibility that we are missing critical components in our discourse, about the conditions necessary for complex systemic change.

What might be different this time?

Investing in systems change

We are in times of increasing social inequities, polarizing politics, climate catastrophes, housing and affordability crises, trauma legacies of colonialism and racism, deteriorating mental wellness of our youth, and intractable mass-media glorification of male violence. In these conditions, the imperative for a whole-of-society response is increasingly apparent. These are systemic issues. They are also gendered issues, as women and gender-diverse people are disproportionately affected. They are systemic patterns that cannot be dismantled with simple, quick-fix solutions, or with new programs, policies, or even legislative change. Of course, these are needed and essential to enact. But they are also insufficient for shifting the conditions that hold GBV and other inequities and oppressions in place.

No one institution, entity, or sector has the capacity to make this kind of wholesale change alone. For years, the burden of addressing GBV and gender-equity shortcomings has fallen on the shoulders of women’s organizations. That burden is heavy in a non-profit sector of low wages, bare-bones resources, minimal if any benefits packages, female or gender-diverse workers, many of whom have lived experience themselves. They work tirelessly to serve some of the most traumatized clients and families, up against the structural and institutional barriers to accountability, justice, and safety. Many still have to do fundraising events to survive. It is unsustainable and the burnout is real.

Altering the trajectory of systemic issues requires many more of us, from different system vantage points, working in concert, connecting dots and amplifying efforts.

Altering the trajectory of systemic issues requires many more of us, from different system vantage points, working in concert, connecting dots and amplifying efforts. This is a long-term proposition, way beyond a single project lifespan or funding cycle, to actually turn the tide. But in the absence of a robust infrastructure for collaborative work across traditional silos, strong and inquisitive relationships across boundaries, and networks of learning that support innovative risk-taking, we will make little progress on these issues. Deep investment will be needed if we are to upskill for change at the systemic level. Systems thinking and systems change is a body of work not often integrated into our everyday lexicons.

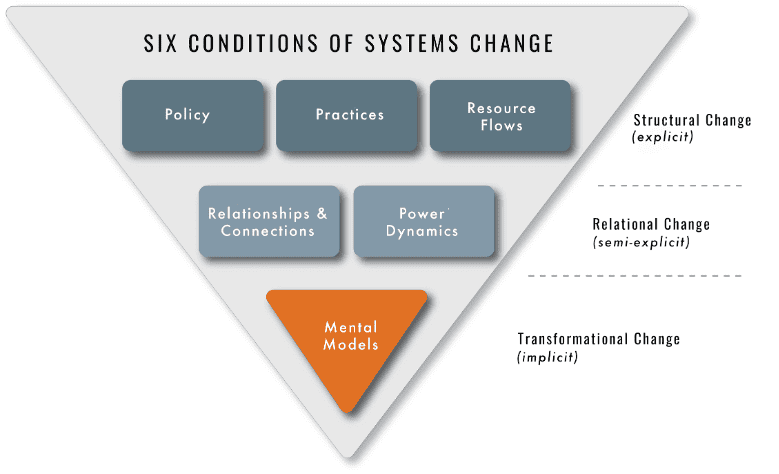

The Collective Change Lab has developed the Six Conditions of System Change model that illustrates where we tend to focus, and the levels we tend to neglect in our nevertheless earnest quest for change.

The first and most superficial level deals with things that are visible to most people in a system and account for the bulk of our work lives: policies, guidelines, practices, strategic plans, budgets, and how information and human and financial capital are allocated.

The second, deeper level examines the quality of relationships, connection, and communication, as well as the centralization or distribution of power, decision-making, formal authority, and informal influence. While we are all in relationship all the time, we rarely acknowledge the significant impact the quality of those relationships and power dynamics have on our individual well-being and also our collaborative effectiveness. They can either elevate and amplify positive change efforts, continual learning, and progress or thwart, frustrate, and stall even the best pathways for action. Investing in partnerships and networks, sharing histories and stories, and fostering equity and belonging at this relational level is the essential infrastructure engine for the transformational-level shifts Turning the Tide Together outlines.

Investing in partnerships and networks, sharing histories and stories, and fostering equity and belonging . . . is essential . . . for the transformational-level shifts Turning the Tide Together outlines.

Mental models are habits of thinking, beliefs, assumptions, and judgments. They are where hundreds of years of racism, misogyny, colonialism, ableism, homo/transphobia, and other “isms” lie embedded in our own minds, in our patterns of perceiving and the worldviews they create. These are the most challenging dynamics to tackle, as they are largely invisible and unexamined. Opportunities and support to explore these are few and far between. It is hard individual and collective work. And if you do it honestly, it is also intensely humbling. But unless we are prepared to see how our own ways of thinking are impeding progress on the things that we say we care about resolving, we will continue to create the same conditions and results we all say we don’t want. Transformational change happens only when we change our individual and collective minds. The two are inextricably linked.

The opportunity at hand

We have in front of us a once-in-a-generation opportunity to make significant systemic change toward eradicating gendered violence for all. Turning the Tide Together, the National Action Plan to End GBV, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, the Desmond Fatality Inquiry, and so many others offer all the evidence base we need, and a blueprint for action. Now we need political will and the dedicated investment to build and sustain the cross-sectoral infrastructure for innovative action that changes our collective minds.

In honour of International Women’s Day, Be the Peace Institute and partners in Women’s Centres Connect and Leeside Society, with funding from Nova Scotia’s Status of Women Office, is hosting a cross-sector summit about GBV and how to move the needle, with Turning the Tide Together and other landmark reports as a blueprint. We will do what John Kania, executive director of the Collective Change Lab, reiterated in a recent webinar: “If you want to change the system, get the system in the room.”

Stay tuned.

[1] Gender-based violence as an umbrella term encompasses violence committed mostly by men, disproportionately against female- identified and gender-non-conforming people. Racial, cultural, and other factors compound prevalence, as members of equity-deserving groups experience significantly higher risks, rates, and severity of harms.

The two paintings at the top of this article are from a series by Emily Powers called Friends and Neighbours that features impactful women in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. On the left is Gail Atkinson, captain of the Nellie Row, a lobster boat with an all-women crew. On the right is singer/songwriter/spiritual practitioner Patricia Watson.

Powers’s portraits place her subjects within imagined worlds, inspired by their realities. “The women I chose to paint are but a few of the incredible folks who make this community great, showcasing a variety of different lived experiences and backgrounds,” she says. “There is so much more to Lunenburg than the UNESCO status, the beautiful buildings, and the history. This is a place where people live, and this series celebrates those who actively work to make this community better for all of us.”