After more than a decade of writing scathing (and often hilarious) critiques on his Nonprofit AF blog, Vu Le shares what’s holding us back, what progressives can learn from conservative philanthropy in the United States, and why he still stays in the sector.

If you know about Vietnamese-American non-profit leader Vu Le (pronounced “voo lay”), you probably have a strong opinion of him. Whether you love him or otherwise likely depends on what side of the table you sit on.

Are you an overworked and underpaid executive director or program manager, burning the midnight oil to (barely) make ends meet? Le is like the outspoken and often hilarious friend you look up to and wish you could speak your mind like he does.

But if you are a wealth advisor or on the board of directors of a family foundation? You may well bristle at being the target of Le’s pointed critiques of the power dynamics in established philanthropy, no matter how well you think you’re addressing them.

This is part of Le’s modus operandi: always punch up (figuratively), never down. He also doesn’t mind looking in the mirror, being open about mistakes, and bringing himself down a notch with a healthy dose of self-deprecating humour. This is why he will likely excel at stand-up comedy, when (not if) he finally pursues that long-held dream to help demystify the non-profit sector for the general public.

But before he does, he has something to share with us. In Reimagining Nonprofits and Philanthropy: Unlocking the Full Potential of a Vital and Complex Sector, he wrote the book he wished had existed when he first entered the sector. “I feel like that might have prevented a lot of things,” he says in an interview with The Philanthropist Journal. Such as? It might have “given permission for me to try different things instead of believing that what we were taught [are] the gold standards.”

In the book, he refers to these as “the nine horsemen of nonprofit and philanthropic ineffectiveness.”

“Our sector can be very set in its way, passing things down through the decades until they become second nature. We normalize philosophies [and] entrench them in our work,” he writes. “Most of the time, we don’t even think about them and how they affect us. They are just there, invisible forces undermining everything we do.”

“A lot of people believe that these are best practices,” he says. “But they’re not. And they don’t really work for a lot of communities.”

How childhood experiences shaped a lifelong passion for the non-profit sector

Le and his family arrived in the United States from Vietnam when he was eight. As he learned English and adjusted to a new life, he endured a lot of teasing at school and found solace in the children’s TV show Care Bears. The kindness of strangers and various non-profits who helped his family in those first months in the United States also proved to be formative on his eventual career path. “I always knew this sector was where I was meant to be,” Le writes in his book. “I wanted to help people the way so many had helped my family. I wanted to build a community. I wanted to be a Care Bear.”

He eventually served as the executive director of two Seattle-based non-profits. Although serving in such visible leadership roles is in many ways a privilege, Le is open about the incredible toll it can take. Shortly after announcing he would step down from his second such position, he wrote about why executive directors of colour are leaving and what the sector needs to do about it. Looking back, it reads as an obvious precursor to his new book.

From blogger to book author

Through his popular blog Nonprofit AF, Le has written more than 600 posts since 2013 on everything from antiquated board models and fundraiser Stockholm syndrome to the Golden Girls as leadership-style archetypes. The reader-submitted “crappy funding practices” has taken on a life of its own, with more than 32,000 people following the LinkedIn page at the time of publication.

It’s hard to be taken seriously when you write a blog called Nonprofit AF.

Vu Le

He feels the blog has been influential but says with a shrug, “It’s hard to be taken seriously when you write a blog called Nonprofit AF.” (“AF” stands for “as fuck”.) He knew he would have to branch out to reach people with power and influence in certain circles. He started writing Reimagining Nonprofits and Philanthropy in mid-2024. Although he was nearly done by the time of the U.S. federal election that November, he rewrote some of it in light of the results. (Chapter 6 is pointedly titled “Building Nonprofit Capacity to Fight Fascism.”)

Each chapter follows a similar structure: a critique of the entrenched mindsets or philosophies in the non-profit sector, the new mindsets we need to develop, and real-life examples of what’s working or different approaches organizations are testing out, capped off with a list of discussion prompts. The book is clear and practical, with a sprinkling of Le’s trademark sense of humour.

Understanding the roots of what’s holding us back

Le identifies nine “horsemen” that he says undergird “basically every single problem” the non-profit sector and philanthropy are seeking to address.

The first one is suppressed imagination. “It seems like we’ve developed this learned helplessness in the sector,” Le says, “because we’ve been taught the systems don’t really change and you’re just trying to help people while you can.” He says this forces people into incrementalism. The imagination deficit is also evident in foundations and endowments that are structured to exist in perpetuity. As he writes in the book, “this reflects an inability to imagine a future where inequity no longer exists, and thus foundations and nonprofits are no longer needed.” So what is the antidote? “We need to regain our vision.”

It seems like we’ve developed this learned helplessness in the sector, because we’ve been taught the systems don’t really change and you’re just trying to help people while you can.

Vu Le

The horseman of self-interest shows up differently in different parts of the sector, severely limiting the potential for innovative and transformative change. Foundation staff are prone to the “golden handcuffs” effect: enjoying cushy salaries, benefits, and perks, yet unable or unwilling to challenge the status quo amidst a culture of complacency.

Interestingly, much of the backlash Le has faced has come not from donors but from fundraisers and wealth advisors. For example, when he started promoting community-centric fundraising, a model rooted in equity and social justice, some fundraisers said it was outright dangerous. “They are a lot more fragile than the donors themselves,” Le says.

Non-profit staff are not immune either. “People do not acknowledge that we have unconscious agendas that help protect the status quo,” Le says. “This is our livelihood now.”

Regardless of what part of the sector we are in, Le implores us to be honest about how our self-interests affect our decisions and actions. Until we do so, he writes, “we’re each at risk of continuing to perpetuate the very injustices we’re fighting.”

The sector is full of really nice people who believe in a just world but who are really more focused on civility and mak[ing] sure that everyone gets along.

Vu Le

Another horseman that stands out to Le is white moderation, which Martin Luther King, Jr., warned about in his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” From Le’s perspective, non-profits and philanthropy have become “one giant white moderate sector.” It’s full of “really nice people who believe in a just world,” he says, “but who are really more focused on civility and mak[ing] sure that everyone gets along.” The implications go far beyond what you might expect. The most damaging aspect? “It prevents us from engaging in political actions and systems change work that are necessary to effectively address the root causes of inequity,” he writes.

Le acknowledges that it will be hard to overcome decades of entrenched philosophies – these and the other horsemen that hold the sector back – but we cannot wait any longer to address them. He says there are three ways to start doing so: reclaim our vision; ground our work in values of equity, justice, and community; and have the audacity of ambition. These can be integrated through all aspects of non-profits and philanthropy, from governance systems, leadership, and work culture, to relationships with funders, hiring, and data. In the chapter on reimagining fundraising and donor engagement, Le says the goal of fundraising should be to create an equitable world. Donors’ main motivation should be justice; they should be seen as partners, not heroes or saviours, and fundraisers should be “agents of justice.” For example, when the Detroit Justice Center accepted a Yield Giving grant, they described it as an act of wealth reclamation and wealth redistribution.

The time to be nice and put up with bullshit – whether from political leaders, funders, corporate partners, donors, society in general, or other nonprofits – is over.

Vu Le

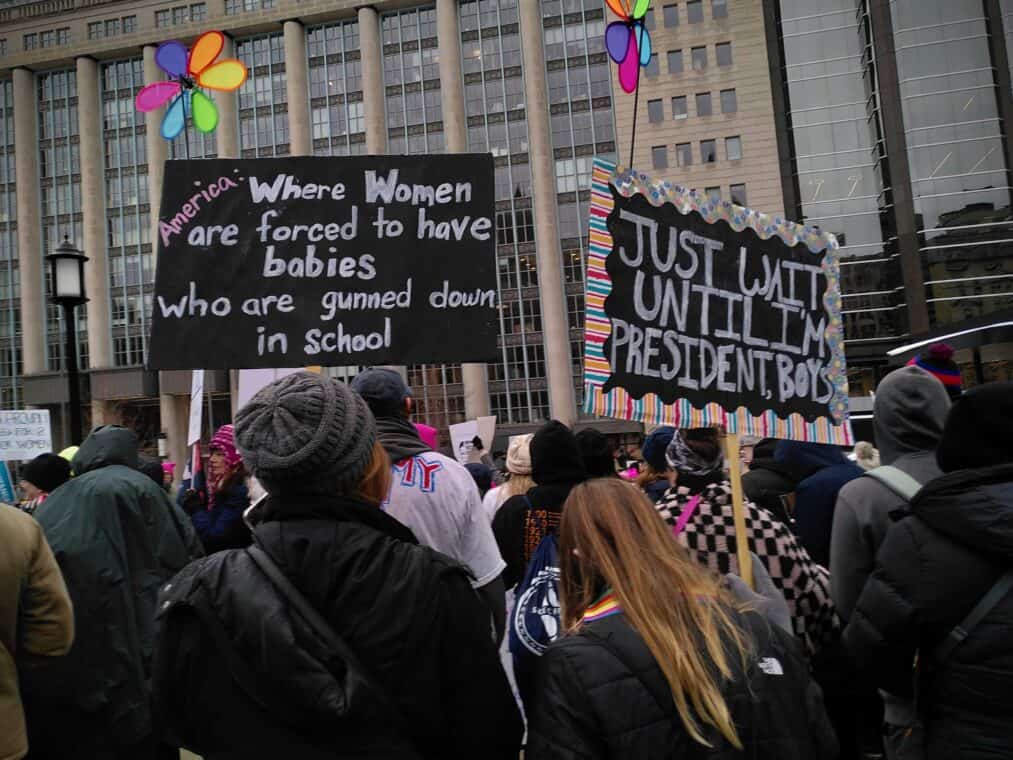

However, Le does not mince words when he describes in his book what we’re up against. With democracies around the world faltering in the face of right-wing extremism and misinformation, massive wealth inequality, an increasingly uninhabitable planet, armed conflict and genocide, and more, he says it’s time for “righteous anger.”

“We need to be angry so we can resist and fight and protect the people and communities we care about,” he writes. “The time to be nice and put up with bullshit – whether from political leaders, funders, corporate partners, donors, society in general, or other nonprofits – is over.”

The elephant in the room: What progressives can learn from conservative philanthropy in the US

Some might perceive the current ascendancy of right-wing conservatism and populism in the United States as rapid and unexpected, as if it is a fluke that came out of nowhere. However, it is anything but – and philanthropy is behind it. For decades, conservative foundations have utilized several key strategies that continue to this day. They pursue a consistent long-term vision and fund an ideological agenda. They provide multi-year general operating support (yes, you read that correctly) to build organizational stability and back key institutions, including in academia, think tanks, political advocacy, religion, and philanthropy. They invest significantly in marketing and media.

This strategic approach to philanthropy has built powerful movement infrastructure to shape public opinion and public institutions, and to systematically advance conservative policy goals. Regardless of your views of the substance and methods, this approach has been remarkably effective at achieving its aims, bearing obvious fruit even in the past few years. As just three examples: Project 2025 (written by dozens of Trump loyalists and published by the Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think tank) became the blueprint for Trump’s second term; a focused campaign against critical race theory and diversity, equity, and inclusion is rapidly changing US universities; and a slate of hand-picked conservative judicial appointments, including in the Supreme Court, is now breaking apart the very foundations of the rule of law.

This is all by design. And at least some progressive activists and movement leaders in the United States think there is much to learn from the overall strategy. Right-wing conservatives are “not afraid to engage in politics,” Le says. “Progressives just refuse to do that. They think it’s beneath them to be engaged in politics.”

“The conservatives have their recipe down,” he says. “We just need to follow it, but use progressive values.”

I really would like our Canadian colleagues to learn from all these horrible lessons we’ve had to learn the hard way [in the United States].

Vu Le

From Le’s perspective, that means getting political and electing people who believe in progressive values and ideals. It means investing in progressive movements and leaders and what is commonly known in the United States as “cultural warriors.” It means building institutions to rival the main conservative think tanks. It means amplifying the truth through independent journalism and countering misinformation.

“I really would like our Canadian colleagues to learn from all these horrible lessons we’ve had to learn the hard way [in the United States],” Le says emphatically. “You gotta take the conservative, right-wing threats seriously.”

What keeps an exhausted non-profit leader going?

There are many reasons why it can be difficult to stay motivated in the non-profit sector. One facet of Le’s relatability is his honesty about sometimes wanting to walk away. “On some of the disheartening days,” Le writes in the book, “I think of leaving the sector and opening a stand at the farmer’s market.”

Yet whatever doubts he may have, he is inspired by the people who keep going, despite the myriad challenges. “I always get pulled back by the fierce determination of my colleagues and the people we serve,” he writes, “and the gravity of the collective mission we are trying to accomplish together.”

He knows it’s important to stay the course, as the work of non-profits and social movements continues across generations. In a sector obsessed with quantitative metrics, non-profit workers and funders have to be prepared to continue planting the proverbial (and literal) trees for the benefit of future generations. As Le writes in his book, “our work creates ripples we may never fully see.”

Although Le has a long and storied track record of no-holds-barred critiques of both the non-profit sector and philanthropy, he wants people to know that it comes from a place of love. “The reality is, I really like our sector,” he says with a curious mixture of resignation and optimism. “If we can just move beyond some of these things that have been holding us back . . . we have a very important role to play right now – even more important than usual.”