Guided by concepts of participatory governance and bottom-up decision-making, national arts service organization Mass Culture is building networks across the arts sector with the long-term goal of fundamentally changing Canadians’ relationship to the arts.

A losing battle over changes to Canada’s copyright laws 10 years ago propelled arts leader Robin Sokoloski down a twisty path toward the creation of a fascinating new national player among arts service organizations (ASOs).

The Canadian government amended the Copyright Act in 2012, allowing universities and colleges to stop paying royalties for a huge portion of the works they were copying and disseminating. According to research conducted at the time by Access Copyright, the collective entity tasked with collecting those royalties, the change would lead to tens of millions of dollars being pulled from the pockets of writers and publishers. Sokoloski was then executive director of the Playwrights Guild of Canada. She and leaders of other ASOs in the publishing sector advocated hard against the change. But it was a failed effort. The Stephen Harper government was not swayed.

Looking back now, Sokoloski identifies two main reasons why their lobbying efforts fell short: one, the government dismissed concerns raised by Access Copyright because the research it had commissioned was seen as self-serving and biased; and two, the rest of the arts sector failed to mobilize around the issue because they didn’t recognize the significance of the policy change – other artists and ASOs didn’t have the time or the energy to grapple with the minutiae of copyright law. “I think that if we had the opportunity to have worked with academia to do research, or someone else that had an unbiased perspective,” Sokoloski says, “then I think that the rest of the sector would have found ways of rallying behind this particular issue, whether it directly affected them or not.”

The failed effort was a bitter blow. But then Sokoloski remembers asking herself, “What else is out there?”

The Playwrights Guild that Sokoloski headed is one of thousands of ASOs in Canada, a heterogeneous, hard-to-define assortment of organizations that range from large regional or industry-specific groups supported by paid memberships to small volunteer-driven community groups working at the local level. Most ASOs operate behind the scenes, at a remove from artists and the art, acting as advocates for their respective fields, in addition to providing other supports like training, networking opportunities, research, community outreach, and promotion. Pointedly, though they may offer financial assistance, ASOs are not arts funders.

Identifying where people are at and trying to find greater connectivity among them, that’s [where Mass Culture] can play a role. We are a network of networks.

Robin Sokoloski, Mass Culture

That open-ended question eventually led Sokoloski and a small group of ASO leaders in 2016 to create Mass Culture (MC) as a volunteer-driven non-profit that sought to identify gaps in knowledge, in research, within the arts sector. They knew there were countless challenges within the sector that could be addressed with better communication channels among ASOs and their members (to counter information silos), more rigorous research (through partnerships with academia and funders), and a network broad enough to unleash the sector’s potential to innovate and mobilize. “Identifying where people are at and trying to find greater connectivity among them, that’s [where Mass Culture] can play a role,” Sokoloski says. “We are a network of networks.”

Working from project grant to project grant, MC grew in fits and starts. It achieved charitable status in 2019, and Sokoloski was named director of organizational development in 2020 (MC has only two full-time staffers). Now seen as a critical catalyst and conduit for research, MC establishes working partnerships across the arts sector, growing connections at the national, provincial, and local levels among ASOs, arts funding bodies, and academic institutions studying the arts and related fields. The immediate goal is to provide practical information, tools, and resources to a sector under considerable stress as it confronts multiple crises: technological, social, and environmental. That’s in addition to the perennial challenge of helping artists earn decent livings, access funding, and find audiences.

We are always tasked as a sector to prove our worth. I think we need to get beyond that . . . The arts deserve [to be seen] at the core of society.

Robin Sokoloski

Addressing these issues is a tall order, but MC has greater ambitions: fundamentally changing Canadian society’s relationship to the arts. “We are always tasked as a sector to prove our worth,” Sokoloski says in a video segment on the MC website. “I think we need to get beyond that . . . The arts deserve [to be seen] at the core of society.”

* * *

This is a banner year for MC as it rolls out a number of signature initiatives: the recent publication of Arts Service Organizations: Positioning a Future Forward, a report identifying key priorities to improve the health of the arts sector; the launch in September of Data Narratives for the Arts (DNA), a publicly accessible database that brings together the financial and operational data of thousands of arts organizations across Canada; and the release of three qualitative impact frameworks designed to help ASOs conduct their own research on the social impacts of their cultural offerings and to track their organizations’ diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. To showcase all this work, MC launched a revamped website in September, in the hope that it becomes the arts sector’s one-stop shop for research and resources.

Knowledge is that commonality amongst us, a very fragmented and diverse sector that has a hard time coming [together] around anything aside from just asking for more money.

Robin Sokoloski

“There is a real need for intermediary roles to support that invisible connective tissue that needs to exist for a thriving sector to exist,” Sokoloski says. “Knowledge is that commonality amongst us, a very fragmented and diverse sector that has a hard time coming [together] around anything aside from just asking for more money.”

When it comes to MC, the “how” is as important as the “what.” From drafting its reports to the design of its research and training projects to its organizational structure, MC is guided by concepts of participatory governance and bottom-up decision-making. “We recognized from the get-go that this could never be a unilateral approach,” Sokoloski says. “There are already way too many arts service organizations. We felt that if we were to create something brand new, it had to be accountable to the sector . . . it needed to include multiple voices.”

“Mass Culture is very intentional about community engagement strategies,” Sokoloski says. “How we engage the public and the arts sector and academia and funders in that research process the entire time throughout – it’s absolutely essential.”

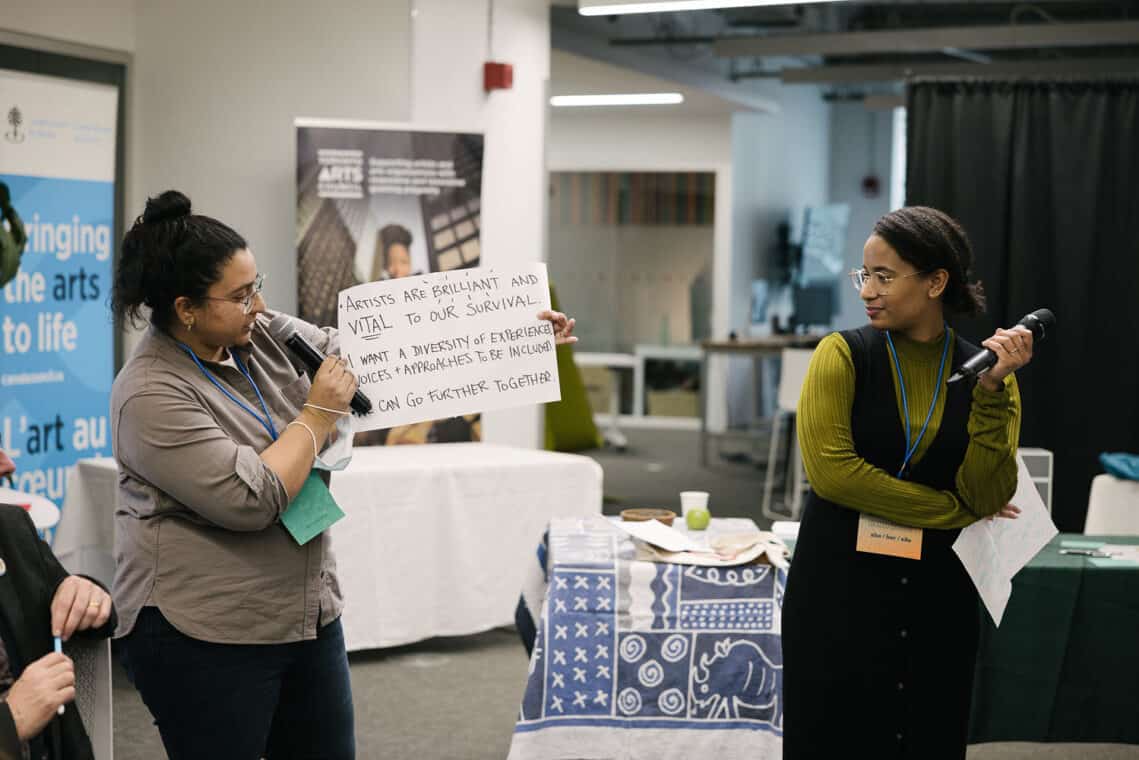

In 2018, MC embarked on a listening tour of the country, partnering with local arts groups who hosted 23 salons with arts representatives, academics, and funders from their communities to discuss a topic of each host’s choosing. The salons were a hit. “There was such an energy and appetite to bring people together just to have a conversation about what they wanted to have a conversation about,” Sokoloski says.

They were trying to surface the concerns of the community so that we would report back to them the kinds of things that were raised, the things that people really wanted to talk about, the things that were bugging them or thrilling them.

Mark Sandiford, CreativePEI

Mark Sandiford, head of the provincial ASO CreativePEI, hosted one of the early salons. “It was astoundingly useful just getting a bunch of people in the community sitting down and talking about stuff,” he says. He appreciated MC’s neutral role as a convener. “They were trying to surface the concerns of the community so that we would report back to them the kinds of things that were raised, the things that people really wanted to talk about, the things that were bugging them or thrilling them. That became a really good foundation for the things that Mass Culture then chose to pursue.”

The exercise wasn’t just a talk shop; it was about establishing relationships and building out MC’s network. And it was about figuring out how to deal with differences of opinion and deep-seated suspicion around the colonial, elitist architecture of arts supports in Canada. Ultimately, the goal was action, impact, change.

“We go by this mantra, a quote from adrienne maree brown: ‘Move at the speed of trust,’” Sokoloski says. “It is so important to us. We will lose our greatest asset, our network, if we don’t. The relationships are everything to us,” she says. “Where the social justice and equity piece comes in is ensuring that we are creating the space and the time and the resources to do this work – not do it fast, not do it cheaply.”

We go by this mantra, a quote from adrienne maree brown: ‘Move at the speed of trust.’

Robin Sokoloski

The salons and other outreach initiatives set the stage for MC’s first national conference, held in January at Toronto Metropolitan University. After crowdsourcing challenges, identifying unifying topics, and voting on which topics to prioritize, MC brought together 140 people (plus 38 virtual attendees) representing 78 organizations nationwide to develop the priorities into actionable “Solutions Pathways” for the sector as a whole.

Sitting atop all this work is the final conference report, ASOs: Positioning a Future Forward, which outlines a sector-wide agenda: growing partnerships and communication channels, increasing investment in research and development (while simultaneously increasing the sector’s capacity to use, evaluate, and shape that R&D), and fostering better equity and inclusion at the institutional level.

MC’s two big data projects – one quantitative, the other qualitative – launched this summer exemplify those priorities.

As non-profits and charities, ASOs must file annual financial reports to the Canada Revenue Agency. Taken en masse, that’s a huge data pool with countless hitherto unknown applications. As of September, the data from 4,000 arts groups is now accessible through MC’s DNA program. The folks at MC recognize that data and the arts may seem like an oxymoron, so they’re leaning heavily into training, launching a learning series for arts professionals designed to scale up the database’s usefulness. By spring next year, 12 organizations that have undergone the training will host demonstration sessions for individuals and organizations in their networks, showing how they used the data to better understand and communicate their missions.

As of September, the data from 4,000 arts groups is now accessible through Mass Culture’s DNA program.

“There is so much call from the organizations I work with to know how COVID has impacted the sector,” Sokoloski says, “whether a lot of arts organizations were forced to close or not. This can tell us that information. There’s been requests to compare salaries across the board; this will allow us to do that. We’ll be able to come up with trends of what’s happening in the sector, [for example] how many organizations in Calgary are successful in fundraising compared to Edmonton?”

The DNA initiative is big. But in some ways, it’s low-hanging fruit, built on existing, readily quantifiable data. Where MC gets into the arty side of arts data, as it were, is with something called qualitative impact assessments, a type of analytical framework that has gained popularity within the arts sector over the last 20 years, ever since the publication in 2005 of a groundbreaking report by the RAND Corporation called Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the Debate about the Benefits of the Arts. In 2019, the Canada Council for the Arts followed suit with its Qualitative Impact Framework.

But qualitative impact frameworks have been used in academic and government policy circles since at least the 1980s; they are popular in the social sciences and healthcare. The philanthropic sector was an early adopter, as funders increasingly demanded better evidence of their funding choices’ effectiveness.

Liz Forsberg is partnerships lead (impact) at the Ontario Trillium Foundation (OTF) and an early supporter of MC. Founded by the Ontario government in 1982 as an arm’s length organization, OTF is now one of the largest funders of non-profits in the country, putting out more than $100 million in grants annually. When Forsberg began at OTF in 2016, the foundation was already using some qualitative assessments, but not in the culture sector. “I think that qualitative impacts can help the sector get better at articulating all the ways that they are engaging with their communities and the kind of outcomes that they’re having,” Forsberg says. “In an ideal scenario, organizations have the resources to be able to collect that kind of information and data from their stakeholders, to be able to make sense of it, and then to be able to make decisions as a result of it, or design better programs or initiatives.”

I think that qualitative impacts can help the sector get better at articulating all the ways that they are engaging with their communities and the kind of outcomes that they’re having.

Liz Forsberg, Ontario Trillium Foundation

“If they can then communicate that in a grant application to any funder, they are probably going to do better,” she says.

But most ASOs, especially the smaller ones, don’t have the time or energy to explore and adopt assessment tools. It’s a conundrum not lost on funders like Forsberg. “We as funders, generally speaking, [have] very high expectations around the kind of measurement that is done by organizations,” she says. “And yet we have not invested enough in capacity [building] and systems needed to be able to do that in organizations.”

Funders [have] very high expectations around the kind of measurement that is done by organizations. And yet we have not invested enough in capacity [building] and systems needed to be able to do that in organizations.

Liz Forsberg

MC’s qualitative frameworks grew out of the Research in Residence initiative that, beginning in May 2021, saw researchers from various universities spending months embedded with local arts groups. The three frameworks released this summer deal with accessibility, climate adaptation, and equity.

Shanice Bernicky, a PhD student at Carleton University, worked with the cross-country festival Culture Days to develop “Spiralling Outwardly for Equity in Public Arts,” a framework that aims to disrupt and reflect on arts organizations’ approaches to DEI. “There’s this disconnect between academia and arts organizations. Both are doing their own [equity] work but never really engaging with each other,” Bernicky says, noting that smaller equity-driven ASOs have been doing this work for decades. “What’s great about doing the work with Research in Residence is the fact that there’s this meeting point of the two. [We’re] not reinventing the wheel.”

CreativePEI’s Sandiford recalls being “surprised and delighted” by the way his group interacted with the researchers. “The scientists were surprised that the artists were that interested in science. And we were surprised that the scientists were that interested in art,” he says. “We thought they would dismiss us as being kind of flaky, but they saw all the potential power that we brought to it. We were having these really lovely adult conversations across these disciplines.”

Funders are an important part of that overall arts and culture ecosystem. And I think there are lots of different things that funders can contribute – beyond just the funds.

Liz Forsberg

Forsberg and other funders were brought in as advisors. “Funders are an important part of that overall arts and culture ecosystem,” Forsberg says. “And I think there are lots of different things that funders can contribute – beyond just the funds. And we’ve seen that in the Research in Residence project, where we had this very active group of funders that formed kind of a steering committee. It was the most collaborative work I think that I’ve done with other funders.”

“One of the principles that the Research in Residence project is based upon is trying to shift the relationship between funders and fundees,” says researcher Emma Bugg, a master’s student at Dalhousie University who worked with CreativePEI to develop “Living Climate Impact.” “Obviously, granting organizations are concerned about how the money they’re giving out is leading to real change,” she says. “But that can lead to real burdensome reporting requirements.”

[Forcing art to conform to funders’ priorities] is not beneficial to those receiving the funds or those giving out the funds . . . The frameworks are a way of facilitating that relationship, to help funders see behind the curtain.

Emma Bugg, Dalhousie University

Artists and organizations often go through painful contortions when trying to force their art to conform to funders’ priorities. “It can – it can, not always – lead to really ineffective reporting that is not a reflection of reality,” Bugg says. “And it’s not beneficial to those receiving the funds or those giving out the funds . . . The frameworks are a way of facilitating that relationship, to help funders see behind the curtain.”

Basically, each of the frameworks is just a set of questions organizations can ask of themselves – their members, audiences, and communities – to assess and track their programming’s various impacts. More than a survey, the frameworks are about nurturing a culture of learning and assessment.

“There’s a more disciplined approach where we say, ‘No, we’re going to think about this harder,’” Sandiford says. “It forces you to see the gaps that you might not have thought of before. Artists are often like, ‘This is going to be great,’ you know? And the idea of taking a few minutes and saying, ‘Yeah, but is it going to be great in this aspect? And is it also going to be great in that aspect?’ And you start saying, ‘Oh, yeah, you know, change a few things, it can actually move those markers as well.’”

The frameworks are customizable; users are expected to refashion them as they see fit. They could even adapt a framework to wholly different ends. The climate framework, for example, might be reworked to track mental health and well-being outcomes. MC will spend the next year studying how organizations end up using the frameworks and whether they prove useful.

“The arts have a different unique value proposition, other than just an arts organization thinking about its carbon footprint or just using arts for propaganda purposes,” Sokoloski says. “By having these indicators . . . it gets the organization to really think [about] how the arts transform mindsets.”

* * *

At Mass Culture, there is a through line from open-ended inquiry to evidence-based action, from those first salons to the new data projects, that connects back to that first question from Sokoloski: “What else is out there?”

The very sort of gangly-ness and weirdness of Mass Culture is part of its great strength. It isn’t positional, it’s inquiry-based.

Mark Sandiford

“What Mass Culture does well is that they’re, like, ‘Let’s step back, find out what’s going on, and then figure out what we need to put forward,’” Sandiford says. “They don’t start, at least as far as I can tell, with any real assumptions, even about what the value of art to society is or what the role of the artist should be in the economy or any of these sorts of things that are kind of givens for a lot of other people before they take their stance.” He likes that MC is prepared to ask those questions and follow a line of inquiry no matter where it leads. “The very sort of gangly-ness and weirdness of the organization is part of its great strength,” he says. “It isn’t positional, it’s inquiry-based.”

“It’s important that we have organizations that can cross and navigate different pieces of a sector’s ecosystem. We see Mass Culture as that intermediary player, the go-between, that brings various actors together to the table . . . and puts them into conversation with each other around shared goals, [then] sharing back what is being learned through this process with the sector,” Forsberg says. “Colleagues on my team at OTF have all worked with other non-profit subsectors like sports and recreation, and they drool over the idea of having something like Mass Culture in their own subsectors.”

Colleagues on my team at OTF have all worked with other non-profit subsectors like sports and recreation, and they drool over the idea of having something like Mass Culture in their own subsectors.

Liz Forsberg

Like most sectors, the ASO sector is rife with buzzwords and jargon. “Knowledge mobilization,” goes one common refrain. But that really is at the heart of Mass Culture. Our current moment is one of profound change, and many in the culture sector see the arts and artists playing a critical role in meeting that moment. A healthy arts sector, where people and ideas – and money – come together equitably, spawns infinite possibilities, those solution pathways that MC likes to talk about. Mass Culture is not about providing answers – it’s about generating the right questions.