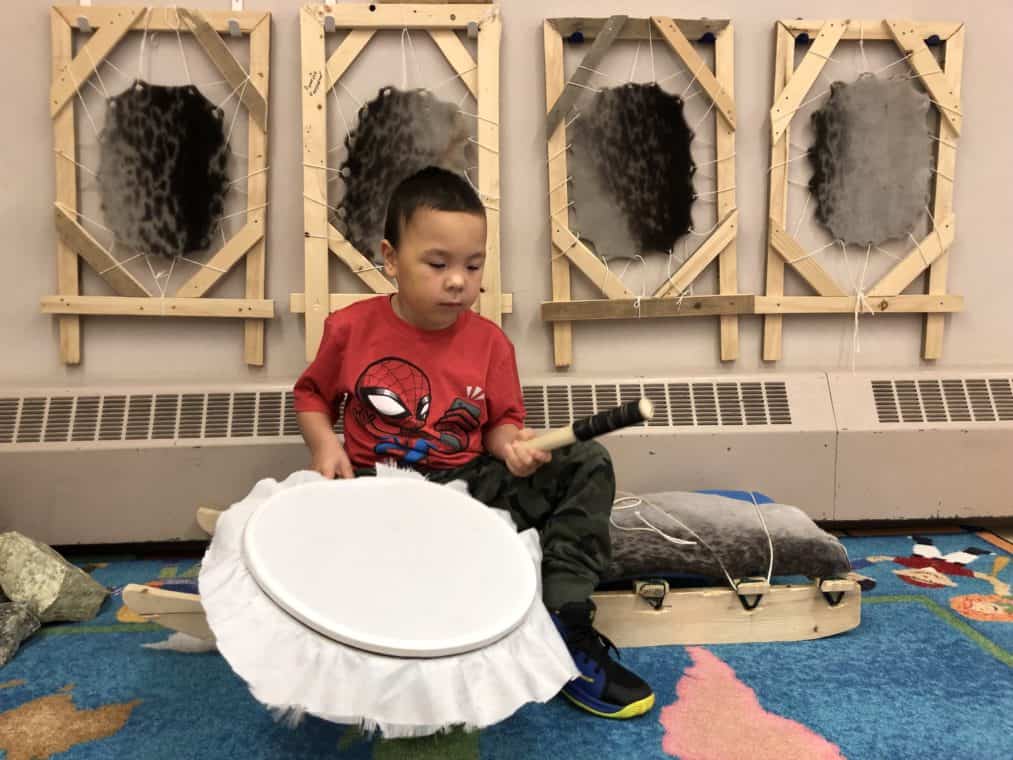

Arctic Inspiration Prize winner Pirurvik Preschool applies the eight principles that embody Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) to provide culturally relevant early-childhood education.

“By the North, for the North,” the Arctic Inspiration Prize celebrates and provides seed funding every year to groups working to develop new and creative projects that solve challenges in the North. There are no limits to the type of initiative that can apply; prizes have been awarded in the spheres of technology, environment, education, socioeconomic development, heritage, arts and culture, and skills development.

***

In 2012, Pond Inlet residents Tessa Lochhead and Karen Nutarak had become increasingly frustrated with the early-childhood-education situation (or lack thereof) in their predominantly Inuit northern Baffin Island community.

Nutarak managed the Nunavut Arctic College in Pond Inlet, had been the chair of the local District Education Authority for several years, and had gone through the school system herself, so she had an intimate knowledge of the educational situation in Pond Inlet, from kindergarten all the way up to college. Lochhead had trained in Montessori education but dreamed of a preschool program that would be more culturally relevant for local children. Both women wanted the children of Pond Inlet to have access to an early-childhood-education (ECE) program based on traditional knowledge and principles, so they could learn, at a critical time in their lives, about themselves, their culture, and their place in that culture.

The topic of early childhood education has been a challenge in Nunavut. According to Statistics Canada, approximately 98.7% (30,140) of Nunavut’s population are Inuit, and of the Inuit population, 13.3% are children aged five or younger. Nunavut follows an Alberta-based curriculum that also adapts material from Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and the Northwest Territories. While the Government of Nunavut’s Department of Education continues to work toward developing a made-in-Nunavut curriculum, the lack of options for culturally relevant education is so far unaddressed. While each of Nunavut’s 25 communities provides K to 12 programming, many communities, especially smaller, more remote ones, have little to no access to preschools or daycares.

According to a 2020 report on early childhood education in Nunavut, the number of regulated childcare spaces was 1,213, while the approximate number of children under the age of five was 4,248.

Compounding the lack of availability is the turnover in ECE teachers. Nunavut’s workforce is very transient, and ECE programs suffer from the lack of consistency in available teachers and daycare workers. More so, there is a notable shortage of Inuit teachers and daycare workers.

The goal was to decolonize education by putting the power of learning in [the child’s] hands, giving them the opportunity to choose how to engage in education.

Tessa Lochhead

As such, for many Inuit children in Nunavut, their first experience with structured learning is at school, when they attend kindergarten. Given the Alberta-based curriculum the school system is built on, many children miss out on the opportunity to learn about traditional Inuit culture and values through a formal educational setting.

***

The Inuktitut phrase “Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit” (IQ) is often translated as “Inuit traditional knowledge” and embodies eight principles:

- Inuuqatigiitsiarniq (respecting others, relationships, and caring for people)

- Tunnganarniq (fostering good spirit by being open, welcoming, and inclusive)

- Pijitsirniq (serving and providing for family and community)

- Aajiiqatigiinniq (decision-making through discussion and consensus)

- Pilimmaksarniq or Pijariuqsarniq (development of skills through practice, effort, and action)

- Piliriqatigiinniq or Ikajuqtigiinniq (working together for a common cause)

- Qanuqtuurniq (being innovative and resourceful)

- Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq (respect and care for the land, animals, and the environment)

Lochhead and Nutarak wanted to provide a learning experience that was guided by the IQ principle Pilimmaksarniq, which allows children to learn at their own pace. They saw an opportunity to create an IQ-guided program enriched by Montessori materials and principles, in which children are trusted to know what they need.

The goal was to “decolonize education by putting the power of learning in [the child’s] hands, giving them the opportunity to choose how to engage in education,” Lochhead says. “We need to look at how to support each child and meet their needs. This is especially important when it comes to early education and creating a sense of safety. It is so important that the first year be a positive experience for the child. We wanted to foster that desire to learn.”

The saying “It takes a village to raise a child” means that an entire community of people must interact with children for those children to grow in a safe and healthy environment. Community members in Pond Inlet came together to talk about how to make culturally relevant items and activities accessible in a classroom setting.

What made Pirurvik appealing was that it was truly ‘Nunavut made’: all of the staff are living and working in Nunavut, the project serves Nunavummiut, it was built around [traditional knowledge], and it is in a small Inuit community.

Adriana Kusugak

Through the tireless commitment of Lochhead and Nutarak, and many others, the first Pirurvik Preschool opened with exceptional success. (The name “Pirurvik,” which means “a place to grow,” was chosen by the committee of parents who advised the preschool project in the early stages.) Young children from Pond Inlet now had access to an early-learning program rich in Inuktitut and Inuit societal values. To observe this first classroom was to witness the dream of Nunavut education in action: young children, adults, and Elders working together in a calm, engaged, and culturally rich learning space.

Very quickly, neighbouring communities heard of the success and reached out to Pirurvik, asking for something similar to be set up in their communities. The challenge now was to take this grassroots effort and develop a model that could be effectively implemented in other communities. As with any growth, funding was needed.

With some support from Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. (Nunavut’s land claim organization, responsible for ensuring that the promises laid out in the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement are carried out), they were able to launch a pilot project in the hamlet of Clyde River. The pilot proved to be very successful. Seeing the value of such programming for their own children, more communities reached out. Lochhead knew that to grow the program they would need more funding to cover the associated costs.

The Arctic Inspiration Prize (AIP) came up for consideration. “It started with a cup of tea,” says Lochhead. They formulated a plan for applying for the prize. The first phase involved bringing the community together in support of the initiative and application; they extended the discussion to local teachers and the hamlet office. More cups of tea were consumed, and support continued to grow.

With the community on board, they began to look at the AIP eligibility requirements. One necessary component was to have some funding in hand to demonstrate their commitment to the project. Lochhead and Nutarak obtained the support of the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, which was instrumental in securing the minimum donation amount required to be eligible to apply to the AIP.

The next step was to gain the support of an AIP Ambassador, so they could be nominated for their project. Lochhead approached Adriana Kusugak, the executive director of Ilitaqsiniq/Nunavut Literacy Council and an AIP Ambassador.

They are paving the way and finding new ways to provide early childhood education, one inclusive of parents as ‘culture first’ teachers.

Adriana Kusugak

AIP Ambassadors are volunteers who act as representatives of the AIP, promoting the prize in communities across the North and encouraging teams to get nominated, supporting them throughout the application process. Ambassadors can be representatives of organizations, universities, research institutes, private sector entities, governments, or any other organization from the North or South with interests in the Canadian Arctic.

The Nunavut Literacy Council’s mission is to empower Nunavummiut (the people of Nunavut) through “Inu-vative” (a phrase coined by the council) programming that combines Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit with essential skills development. “Inu-vation” acknowledges and learns from the past and the wisdom of Elders while finding new ways to support younger generations to actively embrace Inuit culture and language.

“The project checked all of the Literacy Council’s boxes and aligned with our values,” says Kusugak. “What made it appealing was that it was truly ‘Nunavut made’: all of the staff are living and working in Nunavut, the project serves Nunavummiut, it was built around IQ, and it is in a small Inuit community. Because of all this, we knew the project would be successful. It was taking the right approach for building capacity for Nunavut.”

The Nunavut Literacy Council was a recipient of the AIP during its inaugural year and therefore knew what the AIP was looking for in a nomination. “It was an easy ‘yes’” to act as Pirurvik’s Ambassador, Kusugak says.

Many youth programs in the Arctic target school-age children and teens, but very few focus on pre-schoolers. Pirurvik’s unique focus on very young children made its proposal a winner: the project was awarded $1 million from the AIP in 2018.

“We were not surprised that they won. They are paving the way and finding new ways to provide early childhood education, one inclusive of parents as ‘culture first’ teachers,” says Kusugak.

Because of this project, there is now a community of practice, connecting like-minded people and organizations. The demand from other communities reinforces the need for this type of programming in Nunavut.

Adriana Kusugak

With this significant funding, the Pirurvik team was able to establish daycare programs in six more Arctic communities in addition to Pond Inlet and Clyde River: Iqaluit, Igloolik, Arctic Bay, Rankin Inlet, Cambridge Bay, and Taloyoak.

“We have learned so much from their approach and have applied it to our own programs,” Kusugak says. “Because of this project, there is now a community of practice, connecting like-minded people and organizations. The demand from other communities reinforces the need for this type of programming in Nunavut. The Nunavut Literacy Council continues to support them as leaders.”.

Applying for the AIP was a learning curve for the Pirurvik team, but Lochhead says the prize organizers were very responsive to inquiries and also provided prompting questions to ensure the team met the eligibility requirements.

One of Pirurvik’s long-term goals was to offer their program training online, to give more children in the North access to the program. When the pandemic restricted travel, they pivoted, redirecting the funds that were not used for travel into putting their courses online.

“The struggle to find daycare capacity is a big concern in Nunavut,” Lochhead says. “We have been lucky in Pond Inlet and have had consistent staff, but staff turnover is a challenge. There is always new staff to train, and doing that in-person is difficult, especially with the three-week program.”

“COVID actually gave us a good excuse to move the training online. Everything is now digitized and easy to deliver. There are new short videos, which are more digestible. Anyone can go on at any time and take a course,” says Lochhead. “This has been a big learning curve for us but has helped us advance setting up the program in new communities.”

Language is so invaluable for young students, especially learning their traditional language. I knew I had to find a way to integrate it into my class.

Neevee Wilkins

Some in-person training has happened over the last year, however – with one exceptional outcome.

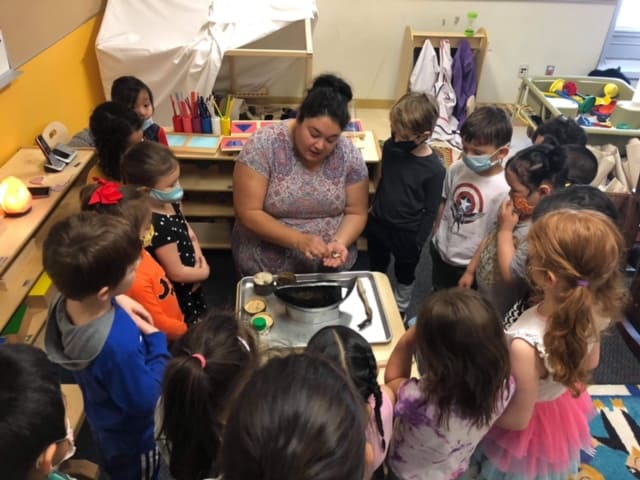

Recently, Pirurvik offered a session at Tundra Buddies, a federally funded daycare in Nunavut’s capital, Iqaluit. One of the participants was Neevee Wilkins, an Inuk elementary school teacher who had taken an educational leave from Iqaluit’s Joamie Elementary School to improve her Inuktitut speaking and writing skills. With 18 years of teaching experience, Wilkins immediately saw the value of a Montessori program built on IQ principals.

“I loved the concept! Language is so invaluable for young students, especially learning their traditional language. I knew I had to find a way to integrate it into my class,” Wilkins says. Soon, she and Lochhead were working on incorporating the Pirurvik programming into Nunavut’s formal kindergarten curriculum.

Wilkins approached Joamie’s principal and vice-principal with the idea, and they threw their support behind her. The next step was the school board, Iqaluit District Education Authority, which loved the idea. They suggested she take a year to pilot the program, but Wilkins knew she needed more time and asked for five. They said yes without question.

“So far, the program has been running in the classroom since the start of the school year, and it has been amazing!” says Wilkins. “Initially, I was nervous about how the kids would learn the alphabet sounds, but they are doing just fine. It is magical. The kids have totally taken to it.”

Wilkins says she has watched kids pretending to clean a seal, another doing math, and another doing art, all at the same time and all learning at their own pace. “I watched a little girl one day, about age four. She took a qulliq [a traditional seal oil and soapstone lamp], an ulu [a short-handled knife with a broad crescent-shaped blade traditionally used by Inuit women], and a pretend fish out of the tent we have in the classroom. She was pretending to clean the fish, something similar to what her family might do out on the land. She was pretending and learning traditional skills – it was magical to see. I have been teaching for 18 years and can’t believe I didn’t think of this earlier.”

“Children work in small groups of four to five. We pull them aside to work on their syllabics and traditional skills. I have the help of a classroom assistant who is a good Inuktitut speaker, and this has been very helpful. Without her, I would not be able to do this successfully,” Wilkins says. In an effort to promote the program and its benefits, Wilkins has offered to provide training to other teachers.

Over the last eight years, the Pirurvik Preschool program has grown from an idea discussed over a cup of tea to a success story. For Lochhead, there is only room for growth. “In fact, there is a long waiting list of other communities that would like to participate in such a program. We are currently seeking funding to set up programs in Baker Lake, Cape Dorset, Resolute, Kimmirut, and another location in Rankin Inlet,” she says.

For others who have an idea, Lochhead offers the following: “Start by going out into the community and find someone to talk with, get their support. Believe in your idea, and others will too. There is lots of support out there as well. The Ambassadors are there to mentor and support you, as well as the AIP team. Reach out to them and they will help you navigate the process – you are never alone. Never give up.”

If you have an idea that you think would create positive change in your community, the AIP is open for nominations annually. The AIP website has all the information you need to apply, including webinars about the prize and how to get nominated. If you or your organization are interested in spreading the word about the AIP and supporting inspiring Northerners and their projects, please visit the AIP website for more information.