The world in which you must act does not sit passively out there waiting to yield up its secrets. Instead, your world is under active construction, you are part of the construction crew—and there isn’t any blueprint.

(Lane & Maxfield, 1995, p. 3)

Public investment in the not-for-profit charitable sector is a tricky business. In recent years, it seems like funders have been in everyone’s firing line, from fund recipients, the media, public auditors, and sometimes each other. Critique of investment practice has created a search for appropriate accountability schemes—ones that justify not only how the dollars are accounted for, but which also look at whether they were invested in the right places. At the same time the sector itself, through

Imagine Canada, is in an extended process of reflection on how to describe just what it is and what impact it can lay claim to in Canadian society. What are sector organizations in relation to public funding—lobbyists and money launderers or actively co-creating a future of public benefit?

This article explores the nature of nonprofit organizing, using a complexity lens to understand how the sector is working and how it benefits Canadians in its unique ability to organize across scale—in communities, across the country and sometimes globally on emerging issues. Faster than government policy structures, at a time and in an environment where speed matters, the sector is able to identify emerging issues, develop knowledge and solutions, and inevitably work to ultimate public benefit. Understanding how it does this is crucial for funders, and to our ability to sort amongst record high demand for funds and reliably select those opportunities for investment that are most likely to create change that works. Six points of “starling wisdom,” hallmarks of organizations that are co-creating the future, offer signposts for funders interested in funding innovation, but they also signal a change in our relationships. Bound in a symbiotic relationship with those we fund, funders, from government departments to private foundations, must also be able to change programs and our practices to make effective investments.

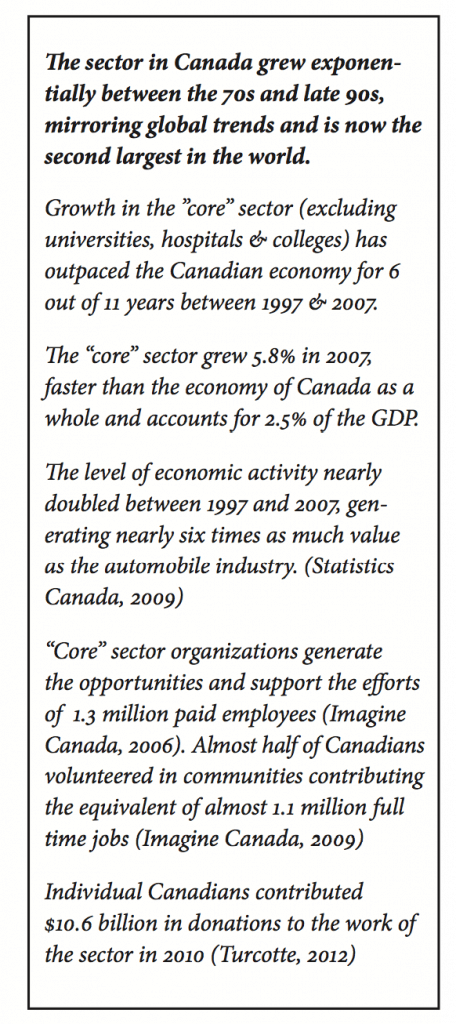

In 2003, the first National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations (NSNVO) showed us the sector as a coherent system. We can now see the sector as having as large an impact on our economy as the mining, oil, and gas industries combined (Imagine Canada, 2006). One hundred and sixty-five thousand organizations, half of them registered charities, and an additional untold number of “grass roots” groups, are vehicles for Canadians righting wrongs, innovating, making art, playing soccer, or caring for others in communities. For many years, the nonprofit sector in Canada has been relatively invisible. How can this be? Organizations that almost every Canadian contributes to as a donor, ticket holder, volunteer, or participant are embedded in a complex system so close to us that we often fail to see the whole.

In 2003, the first National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations (NSNVO) showed us the sector as a coherent system. We can now see the sector as having as large an impact on our economy as the mining, oil, and gas industries combined (Imagine Canada, 2006). One hundred and sixty-five thousand organizations, half of them registered charities, and an additional untold number of “grass roots” groups, are vehicles for Canadians righting wrongs, innovating, making art, playing soccer, or caring for others in communities. For many years, the nonprofit sector in Canada has been relatively invisible. How can this be? Organizations that almost every Canadian contributes to as a donor, ticket holder, volunteer, or participant are embedded in a complex system so close to us that we often fail to see the whole.

Learning to see just how rich and diverse the sector is across the civic landscape is essential to understanding its value. Understanding how it works and how it is changing enables funders to create policy and practice that get the most out of social investments and to monitor how regulation, investment practices, and the economy affect organizations’ abilities to function and to create public benefit. Understanding not only what sector organizations are doing, but also how they are doing it, brings sharper focus to how to support their ability to innovate and create social solutions on an increasingly complex landscape.

The world may feel like it is changing very fast now. Cascades of change seem to ripple and sometimes crash across our landscapes. Whether the focus is on global warming, widening gaps between rich and poor, market collapse, youth suicide, or the need to shrink government deficits—many feel a sense of turmoil. The only certainty is that these are uncertain times. Some experience these times as overwhelming, some are undoubtedly overwhelmed—but for many it is an invigorating time when old assumptions are loosened from their moorings and new ways of doing things become possible. Sector organizations are becoming increasingly important on the Canadian landscape, providing services and solving problems that government or business cannot, or perhaps should not, take up.

In some countries, in times of shift and change, those who feel powerless take up arms when things are not as they should be. Canadians rarely move to defence, but rather pick up the phone and begin to organize: a town hall meeting, a fundraising campaign, a new charity with far-reaching vision—a continuing process of solving problems through the reach for social innovation. It is not happenstance that as the pace of change has accelerated globally and at home, we have seen rapid growth and increasing diversity in sector organizations, despite government cutbacks in funding. Judith Maxwell (2010) tells a story of early days with the Canadian Policy and Research Network, consulting with several longtime sector leaders including Sol Kasimir: “When Sol summarized his view of the sector at that time, he described society as a three legged stool—the public sector the private sector and the nonprofit sector. “But the third leg,” he said, “is a toothpick. We all laughed. [Now] we all know that our days as a toothpick are over. It’s time to think of ourselves as the leaders who can mobilize Canadians to make the country a better place” (p. 1).

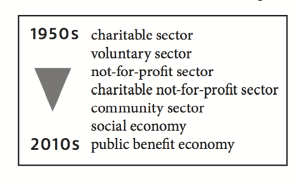

Until quite recently, both funders and sector organizations identified much more closely with their particular area of work than with the civic sector as a whole. Even as recently as five years ago, if you asked a room full of sector organizers “Who is part of the nonprofit sector?” many fewer would raise their hands than if you had asked: “Who is a part of the health sector?” Funders 2 0 10 s charitable not-for-profit sector community sector social economy public benefit economy often have only a narrow segmented view of the sector—the particular groups we fund—and a tendency to extrapolate that view to the whole (Elson, 2007). Likewise, sector organizations may identify much more closely with partners in government as they work together on funding and policy. And why not—what really does a hospice have in common with a soccer club—except for the tradition of people taking up civic organizing to create the opportunities for others that they have come to feel are vital to a sense of community.

The sector has not always known how to think of itself and has been, perhaps, tentative about its role in a social democracy. The evolution of sector naming has become a national hobby for its organizations. Naming conventions change frequently as the collective understanding of the work and social environment shift and have any number of regional variations. Now, a more encompassing language of social economy and public benefit economy (Eakin, 2009) is emerging as the sector claims impact alongside the commercial economy.

The “core” sector includes the 99% of community organizations (excluding hospitals, colleges, and universities) that have fewer than 500 paid employees (although more than half have no employees) and account for the majority of sector revenue, employment, and volunteers. Small and medium sized organizations (SMOs)1 are “the anchor of community life, health and well-being in Canada”—as the deliverers of services and facilitators of participation in community life, they foster innovation and contribute to the economy (Goldberg, 2006, p. 26).

Two views, the long view of sector impact on the economy and on the wellbeing of Canadians and the near view of people organizing on issues that matter in communities, invite a movement across scale, a composite view of Canadian civic life. While perhaps easier to see in its component parts than as a whole, we can understand the sector as a system, a rich tapestry of civic activity that creates an economy of care. As issues and problems emerge, so do organizations and new ways of working, nothing staying constant for long enough to define. What is constant over repeated processes of redefinition of the Canadian sector is the diversity of organizational form and missions that focus on activities of change to produce public benefit. Fleet and ephemeral, the sector holds change at the heart of civic organizing.

Government research and policy structures that inquire into social conditions and solutions have become increasingly curtailed as a result of fiscal restraint. Knowledge development about social issues has increasingly shifted to sector organizations able to draw on issue-specific expertise from both service and experience. By creating dense networks on a particular issue, the sector can encompass and focus multiple views quickly. This composite view offers rich ground for knowledge development and solution to the “wicked” or seemingly insoluble problems that affect communities.

At the intersection with governments, this role both fuels public policy and challenges the social agendas of governments. Adding to the tension, the not-for-profit sector not only creates programs of change, but also constantly changes the ways it goes about doing so. In human organizing terms, the sector can be seen as a natural evolutionary architecture of hope, care, and innovation, and it is getting bigger and much better organized, challenging the ways funders traditionally make decisions to direct their support.

PricewaterhouseCoopers Canada Foundation recently reviewed the literature for emerging trends in the Canadian sector as a backdrop to their 2011 roundtables on capacity building. Building on the American work of the Nonprofit Next initiative (Gowdy et al., 2009), which was funded by several American foundations, they offer a broad view of what is changing. These trends include

• demographic shifts bringing young people into not-for-profit participation

• technological advances that enable broader reach

• networks that enable new ways of working

• rising interest in civic engagement and volunteerism

• blurring boundaries between the sectors

• increasing public scrutiny and demand for accountability and transparency

• new ways of thinking and models for achieving systemic change through large scale, longer-term, multi-stakeholder initiatives (McAlpine & Temple, 2011).

Patterns of change in the sector’s funding economy

Trends in the way funders support sector work have changed as well. Julia Unwin of the Baring Foundation introduces the idea of a nonprofit “funding economy,” which includes all of the sources of funding available to nonprofits, including funds from individual donors, foundations, and governments (Unwin, 2004). The idea of an economy of funders helps us to see how different funders—who may see their work quite separately—are actually part of a system taking up particular roles and contributions. While government funding to charities more than doubled between 2000 and 2009 (Charities Directorate of the Canada Revenue Agency, 2011), it has not kept pace with the growth of the sector. Just how much money is circulating annually in the funding economy is hard to know, but we do know that the total income of the “core” sector more than doubled between 2000 and 2007 (Statistics Canada, 2009). The shape of the funding economy is also changing. By 2007, federal funding was less than 5% of sector revenues, and provincial and territorial governments collectively are now the largest funders of the sector (Statistics Canada, 2009), reflecting governments’ increasing reliance on thirdparty contracting for service. As the shape of the funding economy changes, so have roles and influence.

Sector-government relationship and funding practice reform conversations that began in the federal government through the National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action in Canada (1974) and continued through the Voluntary Sector Initiative (1999), Task Force on Community Investments (2006), and the Blue Ribbon Panel on Grants and Contributions (2006) have now largely shifted to the provinces. By 2010, nine provinces and the NWT had launched initiatives to review their relationship with the sector and several have focused on funding practice reform.2 As provincial and territorial governments have relationships with many parts of the sector, they have the largest influence in the largest part of the sector—organizations concerned with the delivery of service. As social service organizations alone make up almost a quarter of the GDP contribution of the sector (Statistics Canada, 2009), the way provinces and territorial governments think about their funding practice is vital to the welfare of the sector, but also reflects an opportunity to recognize the economic impact created by service-based employment.

The way funders fund is also changing. Shorter-term outcome-based project investments have helped to manage demand, risk, and increased pressure for public accountability. Growth in the number of smaller independent funders such as charitable and community foundations and corporate funders has enabled a broader marketplace of funding opportunity. While more diverse, the contribution of this part of the funding economy is also more volatile, reflecting the impact of market conditions on endowment income and business profit. Ironically, although challenging, the loss of core government funding has freed some organizations from paternalistic relationships with single funders, leaving them increasingly free to create their own innovative policy agenda and “shop” their ideas out to a more diverse marketplace of support.

By 2007, almost half of sector revenues came from the sales of goods and services rather than from grants, contributions, or donations (Statistics Canada, 2009). As they have become increasingly entrepreneurial, sector organizations have addressed the capital shortfall by reinventing the structures of the commercial marketplace. Public-private partnerships, corporate partnerships on social missions, social enterprises, and social mission businesses all sit in the “hybrid space” of social finance.

In 2010, the Canadian Task Force on Social Finance set out a clear course to address the shortfall in capital in the sector by freeing up access to private capital through a marketplace of social finance (Canadian Task Force on Social Finance, 2010). Social Impact Bonds and other forms of nonprofit lending promise sources of more fluid financial support for civic organizations, and preferred approaches to procurement offer new access to government revenues. New organizations like the Community Forward Fund (CFF), the Social Venture Exchange (SVX), and Enterprising Nonprofits (ENP) have begun to act as brokers for nonprofit investors and borrowers, and new structures are continuing to emerge. Foundations attracted by the investment portfolio balance offered by an asset class not tied to the commercial markets are also investing endowment funds in social lending. What is emerging is a blended marketplace of funding and finance, not an either/or, but a both/and proposition that challenges funders to examine both how to support the emergence of social finance and how their funding work fits into a quite different landscape.

Networks and bureaucracies: a cultural disconnect

Some years ago, during the Task Force on Community Investments and Blue Ribbon Panel on Grants and Contributions processes, federal funding departments were invited to participate in focus group conversations on how they understood the sector and opportunities for improved funding practices. In each room, a sharp divide emerged between those who saw sector organizations as “Mom and Pop operations”—poorly run businesses in need of greater monitoring and control—and those who passionately understood the same organizations to be deeply committed to “other-serving” activities that enhance the public good.3 Such a rich arena of change and independent organizing at the border of the bureaucratic structures of government, foundations, and corporations where most funders live makes for unsettled relationships. We need a new metaphor to help us to hold fast to intention within a shifting landscape.

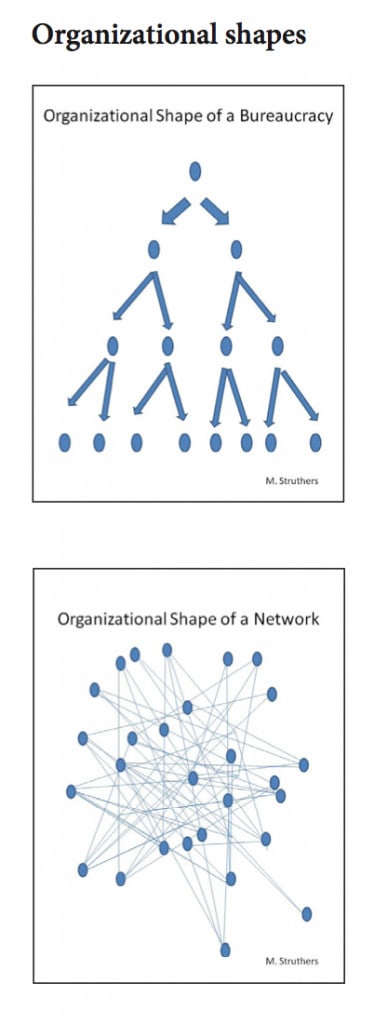

Civic networks and the hierarchies of bureaucratic organizations are two very different “shapes” of human organization (see Figure 1). They process information differently and they respond to different pressures. It is little wonder that the response to the pace of change in the sector from those who hold the purse strings on behalf of both taxpayers and donors has often been to double-down on the mechanisms of sorting, keeping track, ensuring public accountability, and due process. Both forms of organizing have their strengths and there is no doubt that nonprofits build bureaucracies and that every government department has its interpersonal network. The basis of social democracy is in the interface of the complementary roles of civic networks and government bureaucracy. This interface is uneasy and in need of good models for setting expectations and relationships.

Civic networks and the hierarchies of bureaucratic organizations are two very different “shapes” of human organization (see Figure 1). They process information differently and they respond to different pressures. It is little wonder that the response to the pace of change in the sector from those who hold the purse strings on behalf of both taxpayers and donors has often been to double-down on the mechanisms of sorting, keeping track, ensuring public accountability, and due process. Both forms of organizing have their strengths and there is no doubt that nonprofits build bureaucracies and that every government department has its interpersonal network. The basis of social democracy is in the interface of the complementary roles of civic networks and government bureaucracy. This interface is uneasy and in need of good models for setting expectations and relationships.

Through the 1980s to mid-1990s, funders tried to resolve the tension by exhorting civic organizations to look and behave more like businesses. The last decade and a half has brought the practice of funders in Canada under intense scrutiny, particularly those in government. Along with greater competition for funds has come the rising trend toward outcome-based funding, pressure for accountability to audit regime notions of good practice and a steady accretion of administration to ensure that funding decisions are appropriate, and social investment objectives are achieved. Yet while these measures often make perfect sense from the inside, they have all too often created spirals of unintended consequence in the sector organizations that receive funds. The last decade has spawned a history and a literature of sector critique, but perhaps less agreement on good practice, as government bureaucracies tend to tighten and become more rigid with fiscal restraint, and the sector is rapidly expanding connectivity through networked practices and increasing IT capacity.

People’s understanding of organizations has always been built on metaphor drawn from the scientific world. For many years, organizational development has been viewed through the lens of Newtonian science—a mechanistic view that has enabled us to build highly efficient bureaucratic structures by focusing on the interaction of component parts. Like a “well oiled machine,” this view of human organizing sets each cog neatly in its wheel and arranges information and resources to flow through well designed “channels” that support the work of individuals in teams inside departments, relating up the chain of command to the whole. There is no question bureaucracy works—for the kinds of organizing requiring predictability and routine—but what is the metaphor for organizing that holds change as its essence?

Some years ago, statistician Andrea Cavagna took up the study of starlings to understand a much less linear kind of organizing. We have all seen them, thousands of birds flocking across the Canadian landscape in preparation for migration. Somehow they swirl, dip, and funnel, executing collective pirouettes on the slightest shifts in wind, air temperature, and sunlight. No head starling leads, no organizational chart guides movement, no strategic plan predicts the minute changes in the course of individual birds—and yet they get south and do not collide. What Cavagna found using complex statistical analysis is that each bird simply watches the space between the seven birds closest to them—and through that simple rule—stay in a highly complex moving relationship to thousands of other birds. This is the skill set of flocking (Cavagna & Giardina, 2008).

A flock of starlings and the collection of organizations that make up the nonprofit sector, and for that matter the commercial markets, are all complex adaptive systems (CAS). Glenda Eoyang of the Human Systems Dynamics Institute defines a CAS as “a collection of individual agents, who have the freedom to act in unpredictable ways, and whose actions are interconnected such that they produce system-wide patterns” (Eoyang, 2004, pg. 24). These systems operate in ways that are nonlinear—small changes can have big impacts and the patterns they form are directly shaped by their environment and history (Patton, 2011).

Complexity scientists, in the process of reinventing the laws of physics to better explain the natural world, are challenging the old linear cause and effect Newtonian views. Along with the science of quarks, black holes, and fractal imagery, they have offered a rich new source of metaphor for the collective behaviour of people working on the civic landscape, which allows us to understand civic organizing as a natural system—part of what people do where there is the freedom to act. This freedom is a fundamental premise of democracy, perhaps, but also a rich intergenerational tradition in Canada that results in a culture that seeks wellbeing and fosters “other-serving” activity as a way to create it. The collective of this activity generates a system of social resilience that is good for people, but also good for business, channelling the potential for civil unrest into productive organizing for social benefit.

The ability to see system-wide patterns is helpful in times of rapid change. Systemsthinking helps us to see parts of our world as interconnected, to notice unanticipated consequences, unacknowledged interests, differing motivations, rapidly changing circumstance (Williams in Patton, 2011), and sometimes glimpse what might be coming. Understanding the patterns formed by cascades of change on the landscape is essential to the survival of both the delicate bone structure of a starling and the organizations people build to hold new vision and program on the civic landscape.

Those of us who fund capacity building in nonprofits will quickly recognize the sector trend of building networks as it is reflected in grant-making over the last dozen years. As organizations have been forced to belt-tighten around their administrative cores with the shift from core to project-based funding, many have turned to technology to speed up communication and increased the number of exchanges between organizations through networking. The World Wide Web, another complex adaptive system, provides access to a much wider social view and increases potential for relationship. It helps us to see our world as interconnected and highly relational and has made entirely new forms of civic organizing not only possible but also inevitable.

From science to community organizing – understanding the nature of what we fund

Complex adaptive systems are “dissipative” by nature—when left alone, they will lose energy and cohesion and eventually disappear. We hold this natural template as a system of constant change in our physical bodies: we eat, we excrete, we inhale, we exhale the air around us, and when our bodies no longer create this exchange, we die. Simply put, in order to survive a CAS must be in a constant process of exchange with its environment. Understanding the collection of organizations that make the nonprofit sector a CAS is enormously helpful in understanding how it works to create public benefit. The supply of funding and caring volunteers constitute the social forms of energy and exchange that fuel sector work. When an issue or a situation creates enough public concern, people begin to organize. When many organizations with similar interests are created, they link up and begin to work together—or risk becoming isolated from the public resources of time and money—and in the exchange, their work begins to change. When a problem is solved, or public interest shifts, sector organizations and their resources dissemble back into the commons, becoming available for other interests.

Unlike the controlled and machine-like view of a Newtonian organization, a CAS is, by definition, unstable and impermanent, subject to change and in constant relationship with the world around it. Once changed, its parts cannot be simply reassembled into the old pattern: through interaction it has become something else. In nature, CASs are generators of biological innovation, constantly tipping into disequilibrium, experimentation, and reformulation (Gemmill & Smith in Bramen, 1994). This kind of organization not only changes in interaction with the environment, it in turn alters the environment in a symbiotic relationship that evolves both the system and its environment.

Biochemist and philosopher Stuart Kauffman, in his work on molecular biology, explores the organization of living systems and the origins of life. Through the study of mechanical network models that simulate the immense number of chemical interactions that ultimately triggered life on the planet, he suggests that self-organization is as important as natural selection in the creation of life. Spontaneous self-organizing systems begin when a high level of diversity is reached (he is speaking of molecules—we of organizations) and the number of interactions is amplified until “the molecules formed in that primordial soup become catalytic to the formation of others and a collectively [self-organizing] system snaps into existence” (Kauffman, 1995, p. 62). A transformation point is reached and the system begins to live.

In any natural system, molecular or human, where large numbers of interactions between diverse players take place, the components of the system will self-organize in ways that ultimately produce benefit. Nature very quickly discards its failures. As humans, we hold this template for constant change and incremental improvement in our physical bodies and in the organizations and the societies we build. As we emerged from that primordial soup where molecular interaction became complex enough to create breath, so have we evolved; learning to hunt and sew, create organizations, an industrial revolution, an experimental diversity of governments, and a World Wide Web. Spontaneous self-organizing is not an invention of activists and lobbyists, but a replication of the same natural and creative processes that generated life. Like the fractal images we can now understand as endless repetition of pattern gaining in scale and complexity, people replicate our most basic origins in our patterns of social organization. It follows that organizing for public benefit is simply a natural way of innovating and intrinsically linked to the development of human systems and our capacity to evolve.

Scaling, the rapid movement of innovation until it transforms an entire system, happens in a nonlinear fashion, unpredictable and highly dependent on the right local conditions, characteristics that emerge, and history (Paina & Peters, 2011). Far from the linear policy processes of a bureaucracy, given the right conditions, the natural world, and communities, scale innovation automatically in a natural process of self-generation and reproduction of something that works.

Michael Quinn Patton picks up this theme in his work on developmental evaluation, introducing evaluation processes that track emergent learning and process. Co-evolution is about “dealing with the uncertainties of complexity together: looking at the data together, and making sense together [until] a somewhat coherent narrative emerges” (Patton, 2011, p. 144). Futurist and former US Vice-presidential nominee Barbara Marx Hubbard has spent a lifetime linking civic organizing and social innovation to the capacity for human evolution. Founder of the World Future Society in 1966 and later the Foundation for Conscious Evolution, she points out that nature is a hierarchy of symbiotic convergence. Every living thing on the planet acts upon the urge to connect with another and conceive of something new and different in the process. Current crises, dangerous as they may be, are opportunities to invent new social architecture: “On the one hand there is an acceleration of breakdowns. On the other hand, breakthroughs are arising everywhere”(Hubbard, 1998, p. 149).

Civic participation goes well beyond service provision to the work of shaping and reshaping who we are in relationship to our environment—the natural world, the marketplace structures of commerce, and the governments we have created. Innovation is a byproduct of self-organization, and emerges from unpredictability and chaotic conditions, rather than carefully mapped routes. As the sector becomes more densely networked, the numbers of interactions rise and the capacity to generate social innovation increases. Fuelled by funders’ dollars and volunteer hours, the capacity of the sector expands in exact correspondence to people’s desires and energy for change.

Funding in a complex world: complexity meets capacity building

Seeing the sector as a complex adaptive system offers different possibilities for noticing what is going on inside individual organizations. Funders have used a capacity-building lens to help to hold a view of organizations as well as their projects. Mid-2000s thinking about capacity building lead to theories about the component abilities of organizations that contribute to stability: regular funding, strong boards, good fiscal controls, and stable audiences (Connolly & Lukas, 2002). Yet as anyone working in the sector today knows, stability is an elusive and usually temporary condition. The oldest, most “stable” organizations have often had the hardest time staying on the landscape in shifting times. Panarchy, the idea that systems and organizations go through cycles, building and dissipating in relationship to what is occurring in their environments (Gunderson & Hollings, 2002), helps us to accept impermanence, to see that organizations in the sector come and go. When they go, their energy, funds, and volunteers are released back into the public benefit system to contribute somewhere else, in some new way forward.

What should funders be looking for when we seek to fund the organizations that will create the future? Thinking about resilience rather than stability is helpful. Moore and Khagram identify three dimensions of resilience (demonstrating public value, showing legitimacy and support, and strengthening operational capabilities), pointing out that all three dimensions hinge on the ability to collaborate (Moore & Khagramin Maxwell, 2010). Collaboration itself is highly dependent on relational capacity and there are distinct links between relational capacity and an organization’s ability to fund its work (Struthers, 2004).

Across the sector we are seeing the emergence of small, fleet, resilient organizations that can shift and change in a heartbeat, with loose relational structures that allow them to multiply, morph, or join up with others as fast as the landscape changes. Larger organizations are developing a porosity that allows them to bend at the boundaries, change organizational shape, and link with others. Once we would have deemed these organizational forms as “unstable,” but elasticity of organizational form is a vital adaptive capacity in a complex and rapidly changing landscape.

Really, it is all about relationships: the 6 organizational capacities of starling wisdom

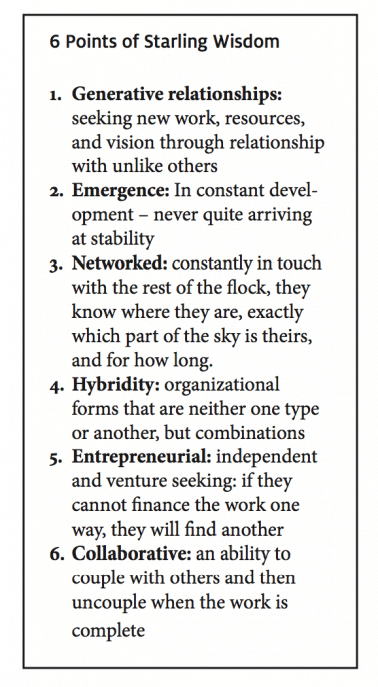

Form follows function in organizational design. Assessing organizational form for the ability to turn on a dime and mobilize a diversity of relationship helps funders to predict which organizations are likely to be able to shape the future. Assessing collaborative projects put forward by multiple applicants in partnership changes the nature of the review and the funding relationship in turn. So what can funders watch for, as signals that an organization or group of organizations has the capacity to innovate and shape the future? What are the organizational forms and capacities that are emerging now?

generative relationships

As the number of new relationships grows exponentially, some offering much needed funding for new initiatives, civic organizers have sometimes worried about mission drift– the tug away from work that meets mission. When the world appears full of possibility, selecting which relationships produce value is a key to effectiveness.

David Lane and Robert Maxfield coined the phrase “generative relationships” to explain the success of ROLM Corporation, a small US telecommunications firm that increased revenue by two-hundred fold over five years by using a relational approach to marketing the emergent technology of private branch exchange (PBX) phone systems to draw market share away from the less adaptive telecommunication giants. By developing deliberately reciprocal relationships with their customers, sales representatives were able to listen to what they needed and then channel feedback on customer desires directly to their engineers to help them to develop innovative products closely aligned to customer interest. Planning, the authors suggest, is not effective strategy when the world is changing very fast. Instead, organizations need relational mechanisms to actively monitor their landscape and co-create with their stakeholders—clients, partners, and funders. In essence, these relationships generate novelty and innovation.

“Generative relationships” intentionally span different perspectives and create something that neither partner could predict in advance or accomplish alone. In times of rapid change, unexamined assumptions become rapidly out of date and begin to limit effectiveness. Intentional pairing across difference (as in the example of the engineer and the customer) helps to disrupt old assumptions that limit choices of way forward (Lane & Maxfield, 1995).

Brenda Zimmerman takes this idea further into organizational methodology. Four relational components she suggests, when held in balance, create new ideas and opportunity. These components include: separateness or difference; talking and listening; action opportunities; and reasons to work together (Zimmerman & Hayday, 1999). If change is a constant in sector work, and innovation is its product, then building relationships across difference is the method.

Emergence

In a Web interview with Carter Bowles, Peggy Homan, author of Emergence and the Future of Society suggests that one definition of emergence is “the learning edge of evolution.” She offers another: “novel, coherent structures arising through interactions between diverse entities in a system” (Bowles, 2011). Emergence then, is the product of a generative relationship. When people in communities organize, drawn together by shared interest or concern, sometimes structure and program begin to emerge simultaneously across communities. These patterns of spontaneous organizing emerge around important issues—and then link up in a network of learning and sharing. Increased connectivity brings new and more diverse perspectives into relationship, focused on common intention, honing method, and articulating the landscape of activity. This process is at the heart of social innovation. Like any natural system, when there is a flow of energy—ideas, volunteer time, and money—from the outside to the inside of a newly developing system, new activity arises. When the flow slows or stops, people lose interest, the effort does not warrant continued interest or investments, and the system slows and begins to dissipate, releasing energy to other ventures.

People self-organizing—at the kitchen table, in the municipal council chambers, in nonprofits and in coalitions—is a messy and very alive process, highly dependent on chance and attraction. Although participants seek common goals, by definition, outcomes are far from certain and novelty abounds. Subsystems and networks coalesce around an issue, develop knowledge, experiment with new ways of doing and then collaborate, merge, morph into something else, begin to hardwire into a more permanent structure around aspects of the work, or simply disappear.

The starling view of the sector focuses on the interrelatedness of organizations’ work, on the movement of the flock rather than individual birds. Direction and outcome are uncertain and funders have a more-than-money role. The wide hawk’s view out over the sector is the privileged view of the funding role. Funders can watch across the landscape, sometimes recognizing patterns of new issues or seeing work beginning to emerge before those engaged in it can. Watching for emergence and contributing knowledge about the new patterns back into the sector are two vital funder roles that support innovation.

Networked Organizing

We all live in networks—some of us are part of a few closely woven networks—family, work groups, communities; others are part of multiple webs of tenuously connected and overlapping connections that reach across interest and community and may span the globe. Network research suggests that it is the loose, distant, and diverse connections that may be the most productive for gaining and trading on new opportunity (Koch & Lockwood, 2010). Tighter connections of cooperation rather than competition build trust and cohesion and set the conditions for risk sharing in innovation (Moore & Westley, 2011). As the capacity for connection increases, so does the potential for innovation. A single person with a telephone is not connected, a few people, each having a telephone, have a privileged sort of communication. Once telephone lines span the countryside and everyone has one, communication is revolutionized and many more activities are possible than they were before (illustration of “Metcalfe’s Law” in Koch & Lockwood, 2010). Scale is required before there is enough interaction for the change to really take hold, and then there is no going back; a tipping point is reached and a new way of relating snaps into being. We have become a people who no longer rely on gathering to connect and do the work of community building and innovation. With access to the Web, our field of organizing just got exponentially bigger.

The Web has multiplied connectivity well beyond tele-technology, creating the possibilities of the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement—loosely connected but powerful forms of network organizing that eschew the usual trappings of leadership and organizational structure. Large scale conversations once required an organization, then a website, and now sometimes only a cell phone. This work has only just begun and as Clay Shirky, author of Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations points out: “The important questions aren’t about whether these tools will spread or reshape our society, but rather how they will do so” (Shirky, 2008, pg. 308). There is much more shift and change in patterns of organizing to come.

Hybridity

Almost every funder will have had to figure out how to apply assessment criteria to an organizational structure that they have never seen before. Turbulent environmental conditions create uncertainty about the future, and in response, organizations are likely to seek structural innovation (Minkoff, 2002). “Hybridity” is a term beginning to be used to describe the structures of organizations that bridge traditional ways of doing things and captures the traditional tendency to experiment with organizational form in the sector. Research is starting to show that organizational structures that are a little bit of this and a little bit of that often improve nonprofit governance and create access to diverse forms of revenue.

While nonprofits have always tinkered with structure to meet mission and make the most of resources, “morph” forms are now increasingly common: a foundation created to raise and fund only its parent nonprofit; a public gallery run by a nonprofit board; a nonprofit home-builder operating a chain of stores selling recycled building materials; an umbrella charity that exists only to incubate new, and not-yet-organized initiatives. Early research suggests that hybridization in organizational shape supports sustainability and effectiveness and aids organizations to respond in a rapidly changing environment (Smith, 2007, 2010).

A new class of “intermediary organization” is taking up the space between civic organizations with the sole mission of enhancing their capacity. Based on principles of sharing, organizations such as the Centre for Social Innovation in Toronto create a deliberately curated space for nonprofit work to grow and find synergistic connection with others (Centre for Social Innovation, 2010; Surman, 2010). Coy and Yoshida (2010) identify three types of these organizations: administrative collaborative, consolidations, and Management Services Organizations (MSO) that help to reduce the cost of administrative services and IT while increasing risk management and quality and sophistication of services. The “morphing” of organizational structure has always been a feature of nonprofit organizing; it is clearly happening now with more variety and at a faster pace than before.

Entrepreneurial

In a curious kind of “push-me-pull-you” process that is characteristic of symbiotic relationships, as funders shifted away from core-funding to third-party contracting and project funding, sector organizations have taken up entrepreneurial structures, necessitating a reciprocal change in how funders fund. Civic organizations that earn, rather than have donated or granted, major portions of their revenue occupy a new “hybrid space,” where the market economy and the nonprofit sector intersect.

Variously called enterprising nonprofits or social enterprises, depending on how they situate structure, mission, and profit, these types of organizations are not new, they just come in greater variety. Now worth more than $3 billion globally, the first Goodwill Store opened in Boston in 1902 as a hybrid structure combining a traditional charitable structure with that of a business.4 Not a single type, but a range of hybrid structures combining the values and mission of public benefit work and the financial structures and revenue streams of business, these civic organizations are creating a new demand for financing. The emerging field of social finance steps away from traditional grants and contributions to new instruments such as social loans, preferred access to procurement opportunities, and community bonds (Canadian Task Force on Social Finance, 2010). Far from an either/or proposition, new organizations are seeking funds from both public funding and financing mechanisms for social purpose.

Collaboratives

Collaboratives are another form of hybridity that offer the opportunity for generative relationships and emergent work. Not only is the work of nonprofits being done inside hybridized organizational structures, they are also increasingly reaching outside their organizations to do it collaboratively. Highly relational and temporary structures, collaboratives transcend organizational boundaries and time, often forming and reforming as the work continues. In a collaborative, work is undertaken by two or more different partners (individuals, organizations, or networks) coming together to work toward common goals (Graham et al., 2010). Often bound by no more than a handshake or a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), they create and fund work together that neither could do alone. Their activities are often hybrid also. Where once we could expect arts organizations to “do” art and social service organizations to “do” service, collaborative ventures link very differently-purposed organizations in work that not only cuts across organizations, but across sectors and expertise.

During the recession of the early 2000s, Lester Salmon’s Listening Post Project identified collaboration as a key mechanism that American nonprofits were using to weather the economic storm (Salamon & O’Sullivan, 2004). During the recent 2008–2009 recession, The Ontario Trillium Foundation polled one hundred of its grantees, with similar results, which suggested that a highly co-operative form of organizing was emerging: “During tough times agencies are often forced to come together to look at what they have in common and how to support each other. Many organizations spoke about partnering with “non-traditional” organizations outside of their sector such as local business, health, and educational institutions and noted that the recession may have accelerated this trend” (Ontario Trillium Foundation, 2009).

Funding for impact requires that we support organizations in collaborative work. John Kania and Mark Kramer, in their recent look at collective impact and work to redress the erosion of the American schools system, look at the difference between isolated and collective impact. They define collective impact as “the commitment of a group of important actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem” (Kania & Kramer, 2011, p. 2). Cross-sector coalitions that engage nonprofits, government, and corporate players, some of whose actions may have contributed to the 6 points of Starling Wisdom

1. Generative relationships: seeking new work, resources, and vision through relationship with unlike others

2. Emergence: In constant development—never quite arriving at stability

3. Networked: constantly in touch with the rest of the flock, they know where they are, exactly which part of the sky is theirs, and for how long.

4. Hybridity: organizational forms that are neither one type or another, but combinations

5. Entrepreneurial: independent and venture seeking: if they cannot finance the work one way, they will find another

6. Collaborative: an ability to couple with others and then uncouple when the work is

complete issues, are required to shift intransigent social problems. Funders’ styles and requirements often foster isolated impact, “a solution embodied with—in a single organization,” like a cure, they suggest “that only needs to be discovered” (Kania & Kramer, 2011, p. 4). Rather, a complex systems approach looks to co-discovery amongst a diversity of stakeholders.

So what do funders look for to fund the future?

So what do funders look for to fund the future?

When we evaluate opportunities for funding, we evaluate the organization’s capacity to do the work, as well as the merits of a particular program. Applying complexity theory helps us to identify the six organizational elements of resilient capacity that are the hallmarks of organizations that will have the ability to innovate and shape the future. They know that they are not alone on the landscape but are actively functioning as part of a complex system, mobilizing their relationship for opportunity and resources—starling wisdom.

As funders, we may find our own relationship with these kinds of organizations challenging. Highly relational organizations will want to make relationships with us—come and visit; seek “face-time,” negotiate terms and conditions. As these organizations are emergent, they may have shifted the project from the beginning of the grant to the final report. Network dwellers will invariably have more information about who is doing what on our shared landscape. Hybrid organizations can challenge what we know about reliability in organizational design. Entrepreneurial organizations will not yet have all of their donors in a row, calling on reviewers’ imaginations to assess their capacity to assemble funding they require. Working with collaboratives challenges us to review and support the work of not one but multiple organizations and also their capacity to work together.

Change is difficult. Funding organizations that work within a public audit narrative of what is “good” in funding practice, particularly, will experience pressure to create objective measures out of highly emergent funding opportunities and to hardwire-in budget lines when flexibility is what is needed for effective investment. Funders working alone will miss opportunities to invest in systemic change –these opportunities are open to those funders who can also work in networks, pooling resources in collaborative funding ventures. And those without the ability to build relational capacity to learn from and with their grantees will quickly lose sight of where the flock is heading.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Lynn Eakin, Jackie Powell, Heather Laird, Paul Chamberlain, Susan Carter, and Liz Rykert who commented on drafts of this article, and to Mark Bloomberg at GlobalPhilanthropy.ca for help with recent Statistics Canada data. Particular thanks to the George C. Metcalf Foundation, who supported this writing as part of a fellowship and generously agreed to the publication of this article in The Philanthropist.

Notes

1. SMEs, on the other hand, are Small and Medium-sized Enterprises representing more than 60% of private sector employment and more than 80% of new job creation. Goldberg (2006) parallels SMEs and SMOs looking at the comparison of impact and of government policy to support impact.

2. These included Ontario, New Brunswick, and British Columbia.

3. Drawn from the author’s experience in facilitating departmental focus groups for the

Task Force on Community Investment.

4. http://www.goodwill.org/about-us/goodwills-history/

References

Bowles, Carter. (2011, November 18). TrendingSideways [Interview]. URL: http://trendingsideways.com/index.php/peggy-holman-emergence-and-thefuture-of-society [March 11, 2012].

Canadian Task Force on Social Finance. (2010). Mobilizing private capital for public good. Social Innovation Generation, MaRS Centre. URL: http://www.socialfinancetaskforce.ca [November 16, 2011].

Cavagna, Andrea, & Giardina, Irene. (2008). The seventh starling. Significance, 5(2), 62–66.

Centre for Social Innovation. (2010). Proof how shared spaces are changing the world. URL: http://s.socialinnovation.ca/files/Proof_How_shared_spaces_are_changing_the_ world_.pdf [August 16, 2012].

Connolly, P., & Lukas, C. (2002). Strengthening nonprofit performance: A funder’s guide to capacity building. St. Paul, MN: Amherst H. Wilder Foundation.

Coy, Bill, & Yoshida, Vance. (2010). Administrative collaborations, consolidations, and MSOs. URL: http://www.lapiana.org/research-publications/publications/articles/ administrative-collaborations-consolidations-and-msos [April 12, 2012].

Eakin, Lynn. (2009). The invisible public benefit economy, implications for the nonprofit sector. The Philanthropist 22(2), 93–101.

Elson, Peter. (2007). A short history of the voluntary sector-government relationships in Canada. The Philanthropist 21(1), 36–65.

Eoyang, Glenda. (2004). Complex adaptive systems CAS. Battle Creek, MI: W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Braman, Sandra. (1994). Entering chaos: Designing the state in the information age. In Slavko Splichal, Andrew Calabrese, & Colin Sparks (Eds.), Information society and civil society: contemporary perspectives on the changing world order (pp. 157–184). West Lafayette, IN: Perdue University Press.

Charities Directorate of the Canada Revenue Agency. (2011). 2009 analysis of government funding of the charitable sector. URL: http://www.globalphilanthropy.ca/images/ uploads/Analysis_of_Government_funding_of_Canadian_Registered_ Charities,_2000-2009.pdf [March 12, 2011].

Goldberg, Mark. (2006). Building blocks for strong communities. Key findings and recommendations. Toronto, ON: Imagine Canada & Canadian Policy Research Network. URL: http://www.cprn.org/documents/44482_en.pdf [August 16, 2012].

Gowdy, Heather, Hildebrand, Alex, La Piana, David, & Mendes Campos, Melissa. (2009). Convergence: How five trends will reshape the social sector. URL: http:// www.lapiana.org/downloads/Convergence_Report_2009.pdf [August 16, 2012].

Graham, Heather, Lang, Catherine, Mollenhauer, Linda, & Eakin, Lynn. (2010). Strengthening collaboration in Ontario’s not-for-profit sector. Toronto, ON: Ontario Trillium Foundation. URL: http://www.otf.ca/en/knowledgeSharingCentre/resources/ OTF_Collaboration_Report.pdf [November 12, 2011].

Gunderson, L.H. & Hollings. C. S. (Eds.). (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Hubbard, Barbara Marx. (1998). Conscious evolution: Awakening to the power of our social potential. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Imagine Canada. (2006). The nonprofit and voluntary sector in Canada: National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations. Toronto, ON: Imagine Canada. URL: http://www.imaginecanada.ca/files/www/en/nsnvo/sector_in_canada_factsheet. pdf [March 17, 2012].

Imagine Canada. (2009). Canadian survey of giving volunteering and participating. Toronto, ON: Imagine Canada.

Kauffman, Stuart. (1995). At home in the universe: The search for the laws of selforganization and complexity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011). Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. URL: http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact [August 16, 2012].

Koch, Richard, & Lockwood, Greg. (2010). Superconnect: Harnessing the power of networks and the strength of weak links. New York, NY: McCelland & Stewart.

Lane, David, & Maxfield, Robert. (1995). Foresight, complexity, and strategy. URL: http://www.santafe.edu/media/workingpapers/95-12-106.pdf [August 16, 2012].

Maxwell, Judith. (2010). The road to resilience: Working together. The Philanthropist, 23(3), 247–258.

McAlpine, Jill, & Temple, James. (2011). Capacity building: Investing in not-for-profit effectiveness. PricewaterhouseCoopers Canada Foundation. URL: http://www.pwc.com/ en_CA/ca/foundation/publications/capacity-building-2011-05-en.pdf [April 9, 20012].

Minkoff, Debra. (2002). The emergence of hybrid organizational forms: Combining identity based service provision and political action. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31(3), 377–401.

Moore, Michele-Lee, & Westley, Francis. (2011). Surmounting chasms: Networks and social innovation for resilient systems, Ecology and Society, 16(1), 5. URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/v116/iss1/art/ [April 6, 2012].

Ontario Trillium Foundation. (2009). In challenging times: How organizations have responded to the economic downfall. URL: http://www.trilliumfoundation.org/en/ knowledgeSharingCentre/challenging_times.asp [April 6, 2012].

Paina, Ligia, & Peters, David H. (2011). Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy and Planning 2011, 1–9. URL: http://heapol.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/08/05/heapol.czr054. short?rss=1 [August 23, 2012].

Patton, Micheal Quinn. (2011). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Salamon, L., & O’Sullivan, R. (2004). Communiqué No. 2. Stressed but coping: Nonprofit organizations and the current fiscal crisis. Baltimore: John Hopkins University, Centre for Civil Society Studies, Institute for Policy Studies.

Shirky, Clay. (2008). Here comes everybody: The power of organizing without organizations. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Smith, Steven Rathgeb. (2007). Hybrid organizations and the diversification of policy tools: The governance challenge. Paper delivered to the Public Management Research Association Conference, October 26–7, 2007. Tucson, AZ.

Smith, Steven Rathgeb. (2010). Hybridization and nonprofit organizations: The governance challenge, ScienceDirect, Policy and Society 29, 219–229.

Struthers, Marilyn. (2004). Supporting financial vibrancy in the quest for sustainability in the not-for-profit sector, The Philanthropist, 19(4), 241–260.

Statistics Canada. (2009). Satellite Account of non-profit institutions and volunteering, 2007. URL: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/13-015-x/13-015-x2009000-eng.pdf [March 17, 2012].

Surman, Tonya. (2010). Creating the conditions for social innovation emergence, March 2010. Toronto: ON: Centre for Social Innovation.

Turcotte, Martin. (2012). Charitable giving by Canadians, Statistics Canada. Cat. 11-008. URL: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-008-x/2012001/article/11637-eng.pdf [May 2, 2012].

Unwin, Julia. (2004). The grantmakers tango: Issues for funders. URL: www.baringfoundation.org.uk/GrantmakingTango.pdf [February 16, 2012].

Zimmerman, Brenda J., & Bryan C. Hayday. (1999). A board’s journey into complexity science. Group Decision Making and Negotiation 8, 281–303.

Marilyn Struthers works in the Province-wide Program of the Ontario Trillium Foundation where she conducts independent research with the support of her employer. Email: mstruthe@otf.ca .