INTRODUCTION

Charitable organizations have a long history in Canada, as in the United States, of caring for disadvantaged populations. During the post-World War II period of the construction of the Canadian welfare state (1945–1975), the contribution of these organizations to the general welfare of the population continued but was overshadowed by state interventionism, which meant that a number of new social programs were implemented in the fields of health and welfare. This modern welfare state was largely inspired by Keynesian economic theory and modeled on the tax-based and publicly administered system proposed by William Beveridge (1942) in the UK. Leonard Marsh (1943) made a seminal contribution in introducing these ideas in Canada, where they became extremely influential in the development of social policy, particularly from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s.

However, the Keynesian welfare state was fully viable only during full (or nearfull) employment. The high unemployment levels witnessed in the mid-1970s, following the oil crisis of 1973, jeopardized the whole system and brought an end to 30 years of very high economic growth—a period often referred by Frenchspeaking authors as the Trente Glorieuses (Glorious Thirty).

The ensuing two decades were marked by frequently high unemployment levels, and the 1975–1995 period can be roughly described as a “welfare state crisis” phase in which budget cutbacks were rampant in both Ottawa and the provinces. For the last 10 to 12 years, Canadians have been living through a confusing transition period characterized by the search for a new “social contract”; debate has been taking place on the respective responsibilities and roles of different sectors, such as government, private businesses, nonprofit and voluntary agencies, and families, in the funding, regulation, and delivery of human services.

This debate is ongoing and, in the emerging post-welfare state period, the various provincial jurisdictions in Canada have preferred and encouraged different configurations of the interface between the state and nonprofit and voluntary agencies. A study of homecare or childcare services available across the country would, for instance, certainly show significant variations in the roles played by government, private businesses, and third sector agencies in these fields.

Regardless of one’s ideological position on the proper role of charities (a subset of the nonprofit and voluntary sector) in the delivery of human services, it must be recognized that, until about 10 years ago, relatively little was known in Canada about these organizations. This is particularly evident when compared to the wealth economics and political science literature on the activities of private sector firms and public sector agencies.

This has now changed, thanks to the contributions of authors such as Keith Banting, Kathy Brock, Laura Brown, Paul Leduc Browne, Jean-Marc Fontan, Michael Hall, Femida Handy, Jane Jenson, Benoit Lévesque, Susan Phillips, Jack Quarter, Katherine Scott, Elizabeth Troutt, Yves Vaillancourt, and many others. This new knowledge is appearing at the time of a new institutional focus on the third sector, ranging from the proclamation of 2001 as the International Year of Volunteers by the UN, to the creation of the Voluntary Sector Initiative (VSI) in Canada in 2000, the conducting of large national surveys (in particular, the 2003 the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations), and the more recent funding of social economy research teams by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

It is in this general context that we present here the results of a survey conducted in New Brunswick. It is part of a growing research effort to better understand the contribution of human services by nonprofit and charitable organizations. In the province of New Brunswick, the knowledge and documentation of charitable human service organizations is scant, and this is probably one of the few provincewide studies in the field. The research focus of our survey has been on types of activities, governance, accountability, location (geography), financial resources (funding), and gender. The specific goals proposed for the study were to:

1. construct a typology of activities performed by human service charities in New Brunswick;

2. describe some of the spatial patterns observable in decision-making;

3. examine the role of gender within these organizations; and

4. identify the challenges that human service charities are facing.

This will help us better understand the charitable human service sector in New Brunswick and identify the role it can realistically play in service delivery.

The first goal is mainly descriptive in nature. The idea was to determine the areas of activity in which New Brunswick charitable human service organizations are involved and what they do.

The second goal is more analytic and is original because it brings a geographic angle to our research. This is particularly relevant when studying a province that is somewhat divided into a northeast French community and a southwest English community. But our interest in geography is not limited to the linguistic divide; it also seeks to examine the size of areas served, the urban-rural split, and the possible differences between purely local (stand-alone) organizations and local branches of larger entities.

The third goal is to examine gender and the female leadership of organizations, and assess how gender might influence (or at least be related to) some organizational characteristics.

Our final goal is to revisit the issue of resources and challenges in the New Brunswick context to see if these are similar to or different from what has been identified in other Canadian studies on the voluntary sector.

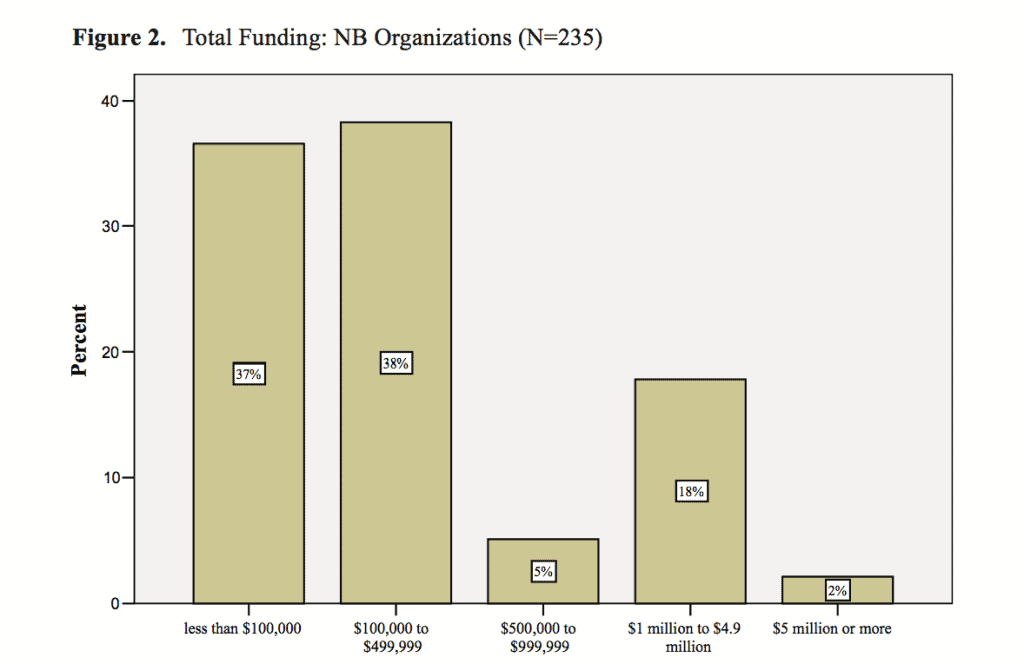

Figure 1. N.B. Organization: Category of Primary Service (N=210)

Methodology

The New Brunswick Charitable Human Service Sector Survey was conducted by mail in 2006. The survey covered questions on the main research themes (typology and service delivery, geography, the challenges of service provision, funding, governance and accountability, and gender). In addition, the survey included a short section on respondent demographics. The sample population consisted of all human service organizations (health and welfare service provision organizations, excluding hospitals) in New Brunswick that, at the time of sampling, held formal charitable status in the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) registry of charitable organizations. The selection of organizations was based on the service category codes designated by the CRA.1 The final sample consisted of 529 organizations; 279 surveys were completed and returned, for a response rate of 53%. Results are presented below under the five main categories of analysis: sector description and typology of services, governance and accountability, financial resources, gender, and geography. Wherever possible, comparisons have been made to studies of the sector on a national level.

Results

An Overview of New Brunswick’s Human Service Sector and its Challenges

Survey data show that within New Brunswick’s human service sector, social services are predominant. The most common areas of service provision are social services (66% state this as the primary area of service), followed by health (16%) and development and housing (11%; see Figure 1). In comparison, the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations (Hall, deWit, Lasby, McIver, Johnson, McAuley, et al., 2004) also found social services to be the most common types of service offered by charities and nonprofits nationally (after religion and sport, which are not included in this study).

Most New Brunswick human service organizations are well established and serve the general public. On average, the organizations that participated in our survey had been providing services in the province for 27 years. Organizations with larger budgets tended to be more established (see Table 1), which appears to conform to logic: organizations grow in capacity (financial and otherwise) over time. Most (68%) served a primarily English-speaking clientele. Almost half (45%) of the organizations stated that their services are targeted to a specific age cohort, the most common of which were senior citizens and adult women. The survey showed that most organizations in New Brunswick (63%) do not have a membership option. This differs considerably from the results of NSNVO survey, which showed that, on a national level, 80% of organizations have a formal membership. This difference may be due in part to the different sampling between this study and the NSNVO survey.2 However, if compared regionally, the results are more similar. Rowe (2006) also found that, compared to the rest of Canada, voluntary organizations in the Atlantic Provinces tend to serve a nonexclusive clientele (i.e., both members and non-members).

Table 1. Relationship of Budget Size to Number of Years in Service

|

Total funding |

Years in service (average) |

|

Less than $100,000 |

23 |

|

$100,000 to $499,999 |

25 |

|

$500,000 to $999,999 |

24 |

|

$1 million to $4.9 million |

38 |

|

$5 million or more |

36 |

|

Total |

27 |

Note: N=227 f=4.718 p<.05

New Brunswick human service organizations vary widely in size, whether measured by the number of paid staff or by total funding. Most of the organizations that participated in our survey (79%) had at least one paid employee. Although there were many (20%) with a large staff base (i.e., more than 20 paid employees), most organizations (55%) would be considered small and had fewer than 10 paid staff. By comparison, in Canada, 88% of all nonprofit and voluntary organizations employ fewer than 10 people (Hall et al., 2004, p.36). Budgets for New Brunswick charitable organizations also vary widely, from as low as $1,500 to just over $9 million (the average budget size is $660,000).

Funding is the greatest challenge facing New Brunswick human service organizations and was cited as the number one challenge by 61% of the respondents to our survey. Altogether, 80% of organizations mentioned funding as one of the three top challenges. The second most common challenge pertained to human resources (recruiting, training, and retaining staff and/or volunteers). Other studies of the sector in Canada suggest that the problem of attracting and retaining staff in the sector is related in part to issues of low compensation and lack of benefits.3

Even well-funded organizations struggle for human resources. Just over 30% of organizations stated a lack of staff or expertise as a major challenge of service provision. Interestingly, the likelihood of this being a problem increased with the size of an organization’s budget (see Table 2). This may be a reflection of the trend of organizations being increasingly reliant on project (i.e., short-term) funding, as has been shown by other studies (Scott, 2003).

Table 2. Relationship of Funding Size to Human Resource Challenges

|

Total funding |

% of organizations identifying staff capacity as a challenge |

|

Less than $100,000 |

10 |

|

$100,000 to $499,999 |

38 |

|

$500,000 to $999,9999 |

33 |

|

$1 million to $4.9 million |

53 |

|

$5 million or more |

60 |

Note: N=206, crv=.36, p<.05

Governance and Accountability in New Brunswick’s Human Service Sector

Having now provided a snapshot image of the charitable human service sector in New Brunswick and an overview of the challenges these organizations face, this section of the article delves into the questions of how organizations govern and structure themselves, as well as how they define and measure success. Other recent studies have also touched upon issues of governance and accountability.4 Where possible, we attempt to highlight these in comparison to New Brunswick findings. We begin by outlining the structure of New Brunswick human service organizations and the composition of their boards of directors.

Organization Structure

Most New Brunswick human service charities are “independent” organizations. To get an idea of the management structure of the sector, we asked organizations if they belonged to a larger group of charities (also know as an ‘umbrella’ organization). Most responding organizations (68%) were independent or stand-alone (i.e., they did not belong to an umbrella organization).

Some marginalized populations are better represented than others on governing bodies. While 28% of organizations had a person with a disability on their boards, cultural minorities and aboriginal people were less likely to have a voice in this capacity (represented in 11% and 5% of organizations respectfully). This apparent representation imbalance may simply be a function of the fact that many organizations in our sample serve people with disabilities, while cultural organizations (as a sub-sector) were not included. In terms of gender, the majority of board members in most organizations were women.

Board size is highly varied and is proportionate to financial capacity. This survey found that the average (as well as median) number of individuals on a board of directors was 10, and that 50% of organizations had between ten and 15 people on the board. When these data are compared to a national board governance survey conducted by Bugg & Dallhoff (2006), boards of directors in New Brunswick organizations appear to be smaller than those in Canada overall.

Decision Making

Most charitable organizations are administered through a board of directors structure, which often necessitates close working relationships between volunteers (board members) and paid staff. Within this, however, there can be a great deal of variation among organizations in terms of how and by whom various administrative decisions are made. Respondents to our survey were asked to state the level of decision-making input that was held by their volunteers, staff, and funders. They were asked to consider this for the following five areas of decision-making:5

1. determining who will be on the organization’s decision-making body;

2. determining what type of activities the organization will undertake;

3. determining how the organization’s activities will be undertaken;

4) determining the kinds of fundraising activities undertaken by the organization; and

5) determining the kinds of accountability measures.

Volunteer input is significant in all areas (over 25% of respondents stated “completely determined by volunteers” for each variable). This may be a function of the fact that most boards are composed of volunteers. The areas where funders have the most input appear to be on accountability measures and on what activities are undertaken by an organization, while they have less influence on governance (who will be on the board) and fundraising.

Table 3. Decision-Making Input Levels

|

Level of decision-making input |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Area of decision-making |

Staff |

Volunteers |

Funders |

|

Accountability measures |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

|

Who will be on the decision-making body |

Medium |

Medium |

Low |

|

Types of fundraising undertaken |

High |

Medium |

Low |

|

What activities will be performed |

High |

Medium |

Medium |

|

How activities are carried out |

High |

Medium |

Medium |

There appears to be a relative balance in decision-making power between funders, volunteers, and staff in terms of the activities undertaken by an organization. Staff, who in most organizations would be most involved in the day-to-day delivery of programs and activities, have the greatest influence on choices about what activities are carried out. In most New Brunswick human service charitable organizations, it is also the staff who exert the greatest influence on how an organization’s activities should be carried out. When it comes to fundraising activities, funders appear to have little influence; staff tend to have the most influence in this area, followed by volunteers (who are often the driving force behind fundraising campaigns, particularly for small organizations).

Accountability and Evaluation

Frequent evaluation is common practice among New Brunswick human service sector charities. In this survey, respondents were asked about whether and how often their organization conducted financial and program evaluations. Most commonly, respondents stated that both financial and program audits were common practice for their organizations. Ninety percent (90%) reported conducting financial evaluations, 86% conducted program and/or service evaluations, and 78% conducted other types of evaluations. Most organizations conducted evaluations once annually. Thirty-eight percent (38%) of responding organizations said they found these to be extremely useful. Most New Brunswick organizations (57%) were evaluated both externally and internally. In comparison, Bugg and Dallhoff ’s (2006) survey on governance has shown that only 48% of organizations conduct formal evaluations. Another national study showed that 73% of voluntary organizations conduct internal evaluations (Hall, Phillips, Meillat, & Pickering, 2003). Therefore, New Brunswick appears to be leading in this regard.6

Our survey asked respondents to state to whom they were currently most accountable. Most organizations reported that they were primarily accountable to a government body (municipal, provincial, or federal). Other frequently cited bodies included members, funders, an umbrella or parent organization, and the community. In contrast, when asked to whom they felt their organization should be primarily accountable to, the most common response was patrons/members. While most organizations (75%) are in agreement with who they are currently accountable to, the results seem to indicate that current accountability practices are perhaps not centered enough on service users.

Sustaining the Sector: Financial Resources and Funding

We noted earlier that the size of budgets within New Brunswick organizations varies greatly. In this section, we provide a more in depth analysis of the financial capacity of the sector, looking in particular at the sources and size of income by sub-sector compared to national data. We also examine the relationships between organizations and their funders.

It is worthwhile to first consider that the nonprofit sector is an important contributor to the national economy. In fact, the rate of economic growth in the nonprofit sector exceeds that of the economy as a whole (Statistics Canada, 2006). The Canadian nonprofit sector contributed 7.1% to the national GDP in 2003, more than some of the major sectors, such as the retail, mining/oil/gas, and agriculture. If hospitals and universities are excluded (as they are in our New Brunswick sample), the contribution is lower but still represents 2.6% of GDP ($29 billion). The rate of growth for this ‘core sector’ (nonprofits, excluding hospitals and universities) is greater than that of the nonprofit sector as a whole. This suggests that the core sector (within which the organizations of this study fall), although its economic girth is much smaller than hospitals and universities, is growing in size and economic importance (Statistics Canada, 2004). It could even be speculated that many of the financial challenges highlighted by the voluntary sector literature (including this study) are attributable to ‘growing pains’ as the sector expands within a climate of reduced funding.

Budgets

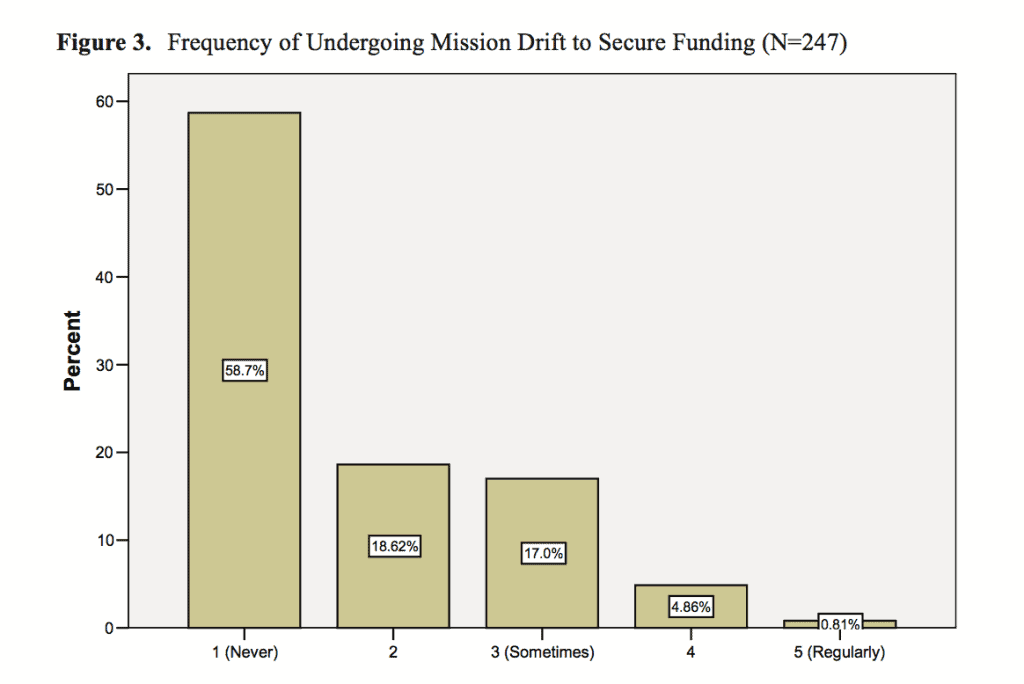

Most charitable human service organizations in New Brunswick operate on small budgets. As noted earlier, the budgets of the organizations surveyed ranged from $1,500 up to $9 million, with an average budget of just under $660,000. By comparison, according to the NSNVO (Hall et al., 2004), the average income for registered charitable organizations (of all types) in Canada was $786,094. Most New Brunswick organizations in our sample would be considered small; three quarters operated on budgets of less than $500,000 (see Figure 2). The same pattern was found by Hall et al. in the sector at a national level, where approximately 90% of organizations had budgets of less than $500,000.

Figure 2. Total Funding: NB Organizations (N=235)

Organization budgets vary by sub-sector. Among the responding organizations in New Brunswick, the social services sub-sector had the largest average budgets ($795,987 on average), followed by housing and development organizations, and health organizations. Although this pattern is not statistically significant, it allows us to compare New Brunswick sub-sectors to the national trends (see Table 4). Findings from the NSNVO study also showed that organizations whose primary area is social services tend to have higher revenues than other human service sub-sectors.7

Table 4. Sub-sector Organizational Budgets in New Brunswick and Canada

|

Sub-sectors (primary service) |

New Brunswick: average budget (N=183) |

Canada: average budget (NSNVO) |

|

Social Services |

$795,986 |

$583, 599 |

|

Development & Housing |

$646,223 |

$540, 657 |

|

Health |

$533,198 |

$1,723,082 |

|

Other |

$188,150 |

$620, 189 |

|

Law & Advocacy |

$176,413 |

$386,623 |

|

Grants, Fundraising, Volunteerism |

$26,000 |

$517, 916 |

There is also a relationship between budget size and the human resources capacity of organizations (see Table 5). Organizations with larger budgets tend to have the highest number of staff. While not statistically significant, the same pattern is also seen for volunteers. Although organizations with large budgets have the most staff, they are also more likely to identify staffing as a challenge of service provision. In other studies, the same trend (i.e., staffing as a challenge is positively related to budget size) has been observed for the Atlantic Provinces and for Canada as a whole (Hall et al, 2004; Rowe, 2006).

Table 5. Relationship Between Budget Size and Human Resources Capacity

|

Total funding |

Average total volunteers* |

Average total staff ** |

|

less than $100,000 |

27 |

2 |

|

$100,000 to $499,999 |

33 |

6 |

|

$500,000 to $999,999 |

97 |

19 |

|

$1 million to $4.9 million |

302 |

55 |

|

$5 million or more |

143 |

187 |

*N=215 f=1.2 p= .29

*N=215 f=187.1 p=<.05

As mentioned earlier, our survey asked about the relative influence of volunteers, funders, and staff within organizations. Survey data indicate that organizations with large budgets are under tighter control from funders, while decision-making in small organizations is heavily influenced by volunteers. They also show a significant relationship between the size of an organization’s budget and how much control funders have over activities. Funders tend to have more say within organizations with large budgets in determining both the type(s) of activities the organization will undertake and how the activities will be carried out. On the other hand, volunteers tend to have more influence over decision-making in organizations with small budgets. Over 50% of organizations with budgets of less than $100,000 stated that the organization’s activities are completely determined by volunteers. The level of input staff has on organizational decision-making, however, does not appear to be related to budget size.

Our survey results show that the education level of an organization’s leader is positively related to size of budget. This is not surprising since organizations with larger budgets are more capable of attracting highly educated employees; at the same time, the demands of managing a large budget may require large organizations to employ leaders with more formal education and/or training.

Source(s) and Stability of Funds

Scott (2003) has shown that there have been shifts in the way organizations generate revenue the nonprofit sector. Cuts in government funding have led many organizations to a dependency on diverse sources of short-term, unstable funding. One of the most pronounced trends of this new funding regime has been the shift to targeted, project-based funding and a decrease in the amount of core funding available to run voluntary organizations on a day-to-day, year-to-year operational basis. Some of the questions in our survey shed some light on how organizations in New Brunswick are being affected by this trend. In some instances, the results are surprising.

Government is a key funder but, in most cases, is not the primary funder. According to our survey, most New Brunswick human service organizations depend on government for at least a portion of their funding, but the majority (55%) receive less than half of their revenue from government sources. By comparison, the NSNVO survey showed that 36% of the revenues in the Canadian core nonprofit sector (excluding hospitals and universities) comes from government sources (Hall et al., 2004).

Larger organizations rely on a higher proportion of government funds. While there seems to be no specificity in terms of the type of service providers receiving government funds, there is a significant pattern of organizations with a high proportion of their funds from government tending to have larger budgets in our New Brunswick survey (see Table 6). The same pattern is exhibited at the national level (Hall et al. 2004).

Table 6. Percent of Funding From Government Sources, by Size of Budget and Percentage of New Brunswick Human Service Organizations

|

Percent of funding from government sources |

Average budget |

% of organizations |

|

0—25 |

$252,553 |

40 |

|

25—49 |

$274,018 |

15 |

|

50—74 |

$882,598 |

13 |

|

75—100 |

$1,304,574 |

31 |

N=223 f=10.73 p<.05

Government-funded organizations face fewer financial challenges but are under tighter control by their funders. The level of input from funders on decisionmaking was significantly and positively related to the proportion of funding received from government sources. In fact, organizations deriving more than half of their funds from government were more likely to state that they had high input from funders on the type(s) of activities carried out, how those activities are carried out, and measures of accountability used by the organization (see Table 7). When asked to rate whether their mandate was respected by their funders, organizations that receive the majority of their funds from government were also more likely to report that their mandates were not respected by funders and slightly more likely to state that they had problems with the reporting requirements of funders. These organizations were also less likely to report financial limitations as their primary challenge of service provision and more likely to have a high level of core funding (84% reported that two thirds or more of their budgets were allocated to core operations). The impression given by this data is that government-funded organizations are faring better financially but have more problematic relationships with their funders.

Table 7. Areas in Which Funders have High Levels of Decision-Making Input, by

Percentage of Total Funds Received From Government

|

Areas in which funders have high levels of decision-making |

% of organizations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Areas in which funders have high levels of decision-making |

Less than 50% of total funds come from government |

50% or more of total funds come from government |

|

Types of activities* |

16 |

48 |

|

How activities are carried out** |

11 |

32 |

|

Accountability measures*** |

19 |

66 |

* N=183 crv=.47 p<.05

* N=182 crv=.381 p<.05

**N=183 crv=.519 p<.05

Funding stability is major concern for the nonprofit sector. On a national level, Gumulka, Hay, and Lasby (2006) pointed out that 61% of small and mediumsized organizations in Canada report an over-reliance on project funding. However, our New Brunswick results show that, generally, organizations are dedicating most of their budgets to core operations. On average, organizations allocate 71% of the budget to core operations (and the remaining portion to special projects). While care must be taken not to interpret this as an absence of struggle for core funding, this does tell us that most New Brunswick organizations devote the majority of their money to operating their organizations on a day-to-day basis. Our survey data also show that organizations that devote a lot more of their budgets to core operations tend to have bigger budgets overall (see Table 8). However, this trend is related to the fact that these organizations also tend to have more paid staff (which is most likely their greatest budget expense).

Table 8. Budget Allocated to Core Operations Relative to Revenue

|

Percent of budget allocated to core operations |

Average size of budget* |

Average number of staff** |

|

Low (0–33%) |

$182,265 |

3 |

|

Medium (34–65%) |

$370,679 |

15 |

|

High (66–100%) |

$796,038 |

21 |

*N=187 f=4.03 p<.05

*N=180 f=4.56 p<.05

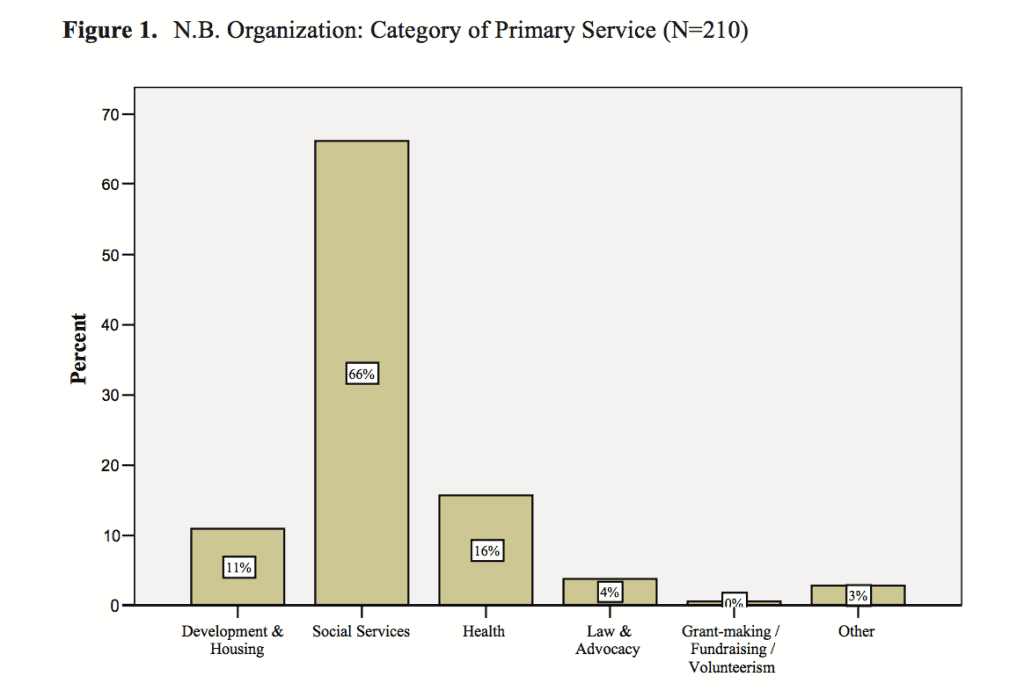

Mission drift is problematic but not prevalent among human service organizations in New Brunswick. Less than half of the organizations surveyed had shifted their focus (i.e., undergone mission drift8 ) in order to secure funding, and less than 1% experienced this on a regular basis (see Figure 3). Therefore, mission drift, although present, is not as prevalent as we may have expected. While the data are not directly compatible,9 this information is available from a national level study as well. Scott (2003) shows 33% of organizations experiencing mission drift (p. 150).

Figure 3. Frequency of Undergoing Mission Drift to Secure Funding (N=247)

Much has been written about the difficulties nonprofit sector organizations have experienced with reporting requirements. Our survey asked organizations whether they had experienced problems with the reporting requirements of funding agencies. Among New Brunswick organizations, less than 25% experience problems with the reporting requirements of their funding agencies, with less than 5% stating that it was a serious problem.

Respondents were also asked to rate the extent to which they felt their mandate was respected by their funders. Most organizations (54%) felt that their mandates were completely respected by the funders to whom they report, and less than 5% stated that their mandate was not at all respected. Such low incidents of problems with both reporting to funders or having their mandates respected by funders suggests that New Brunswick organizations may not be under the same pressure to conform as some analysts may have thought, and that they may be coming to accept the reporting demands placed upon them.

Relationships Between Size of Budget and the Challenges of Service

Provision

Regardless of the size of an organization’s budget, funding was the most frequently cited challenge of service provision. While it might be expected that organizations with small budgets would tend to report having funding and financial challenges, in fact, the problem of funding seems to be common to organizations of all sizes.

Challenges related to lack of expertise and staff are not determined by lack of financial capacity. Organizations that reported lack of staff and expertise as their primary challenge have larger budgets on average than most organizations, suggesting that human resource and expertise problems are not necessarily rooted in financial capacity alone (see Table 9). Those organizations that identified volunteer capacity as their biggest challenge, on the other hand, had the smallest budgets, on average.

Table 9. Service Provision Challenges and Budget Size

|

Primary challenge in providing services |

Number of organizations |

Average budget |

|

Financial limitations/fundraising |

130 |

$720,362 |

|

Geography/distance from patrons |

12 |

$282,456 |

|

Lack of staff/expertise |

18 |

$1,386,243 |

|

Resources/infrastructure |

12 |

$325,198 |

|

Lack of volunteer capacity |

15 |

$79,382 |

|

Issue awareness/communication |

9 |

$925,833 |

|

Other |

9 |

$1,563,797 |

N=205 f=2.30 p<.05

Women’s Work: Gender Demographics in New Brunswick’s Human Service Sector

Although the Canadian voluntary sector as a whole is predominantly staffed by women, there has been relatively little extensive research conducted on the gendered nature of the sector. Some have speculated about the reasons for the high concentration of women in the sector, pointing to such possibilities as the:

traditional concentration of women in caring occupations, like health and education; nonprofits may offer more flexible working arrangements that are attractive to women seeking to balance work and family-care responsibilities; or nonprofits may offer women greater opportunity to assume senior management roles than is the case for other sectors. It may also be the case that relatively fewer men are willing to accept the kind of work and working conditions that the sector is able to offer. (McMullen & Schellenberg, 2002, p.8)

New Brunswick’s charitable human service sector is also highly gendered, with women playing a dominant role in staffing and volunteering. On average, more than 80% of employees are women. In this section, we delve deeper into the relationships between gender and the operational realities of the sector. We start by describing differences in the gender breakdowns among organizations’ staff, managers, and boards, followed by a discussion on gender among various service areas, and the relationships between budget size and gender composition.

Gender Composition in Organizations

Human service organizations in New Brunswick are largely female-staffed and female-led. Women made up the overwhelming majority (80%, on average) of the employee base of the organizations that participated in our survey. The majority of volunteers (more than 65%, on average) were also female. Most (68%) of the leaders of the organizations that responded to our survey were women. There were more women than men on these organizations’ boards of directors as well, but the percentage of men was slightly higher at this level (42% men vs. 58% women).

Development and housing organizations had the lowest female representation of all the sub-sectors. Compared to other service areas, women accounted for a smaller percentage of staff in housing and development organizations (65% compared to 80% for all service areas). Development and housing organizations also tended to have fewer women on their boards, relative to other areas. Hence, it seems that this type of organization exhibits a more traditional male management/female staff pattern as far as New Brunswick charitable human service agencies are concerned. Health organizations, on the other hand, tend to have the highest female representation of all service areas, which matches national trends (Pay Equity Task Force, 2004).

While it is clear that the sector is powered by women, their level of influence appears to decrease proportionately to the status of the positions within an organization. As shown in Table 10, the ratio of female representation changes as one goes up the hierarchy; there are higher proportions of women among volunteers and staff than among leaders and board members. This trend can be interpreted as being a proportionate to the perception of status (with staff and volunteers at the lower end of the scale, and managers and board members at the higher end).

Table 10. Gender Representation Among Volunteers, Staff, Leaders, and Board

|

Positions within an organization |

% female |

% male |

|

Volunteers (median, n=279) |

71 |

29 |

|

Staff (median, n=279) |

91 |

9 |

|

Leaders (total responding leaders n=218) |

69 |

31 |

|

Members of the board (median, n=279) |

57 |

43 |

The phenomenon of women occupying (proportionately) fewer positions at the managerial level is not unique to New Brunswick and has been documented in previous studies as well. For example, it has been shown by Prince (1988) that men were more likely than women to say that they had supervised other volunteers (22% vs. 14%), sat as a board member (29% vs. 20%), and helped run the organizations (35% vs. 27%). Similar trends have also been documented by Dow (2001).

Results from our survey show that organizations with larger budgets tend to have lower percentages of female board members than do organizations with small budgets (see Table 11).10 Staff size and management gender may be related. While women managed the majority of the organizations in our sample, organizations with larger staff capacity were more likely to be managed by women (see Table 12). This trend is not statistically significant, however; because the sample has such a low level of variance in terms of staff gender, the patterns may be difficult to detect. These trends (of gender specificity relative to size of the organization) are not exhibited at the level of staff or volunteers.

Organizations that had more women board members also tended to employ more women. Among the organizations that responded to our survey, those that had higher percentages of women on their boards also tended, on average, to have more female staff and more female managers (see Table 13). The same was true for the proportion of female volunteers—the more women on the board, the higher the proportion of female volunteers.

Table 11. Gender of Board in Relation to Budget

|

Annual budget |

% of male board members |

% of female board members |

|

Less than $100, 000 |

35 |

65 |

|

$100, 000 to $499,000 |

42 |

58 |

|

$500,000 or more |

48 |

52 |

N=223 f=4.85 p<.05

Table 12. Gender of Managers in Relation to Size of Staff

|

Number of paid staff |

% of male managers |

% of female managers |

|

0 to 5 staff |

21 |

79 |

|

6 to 10 staff |

27 |

73 |

|

11 to 20 staff |

17 |

83 |

|

More than 20 staff |

15 |

85 |

Table 13. Gender of Governing Body in Relation to Gender of Workforce

|

Women on board |

% females on staff (mean, n=190) |

% females in management (mean, n=224) |

% of female volunteers (mean, n=176) |

|

50% or less |

70 |

41 |

50 |

|

More than 50% |

86 |

73 |

76 |

Leadership Gender

Our survey asked respondents to state their role within the organization (i.e., staff, manager, volunteer, director) and their gender. This section presents some of the data comparing leadership gender to challenges faced by New Brunswick human service organizations.

Organizations led by women and men were equally likely to experience financial challenges in service provision, and there were no significant differences in terms of the relative budget size of organizations led by men and those led by women. This differs from the results of a study conducted by Thériault (2003), which found that organizations led by men tended to have larger budgets. Our study shows that organizations run by women tend to have more women on their boards (see Table 14). Organizations led by women also tend to employ a higher percentage of women (see Table 15).

Table 14. Gender of Organization’s Leader by Percentage of Women on the Board

|

Women on board |

% of organizations led by women |

% of organizations led by men |

|

50% or less |

31 |

65 |

|

More than 50% |

69 |

35 |

N=218 crv = .347 p<.05

Table 15. Gender of Organization’s Leader by Percentage of Women on Staff

|

Women on staff |

% of organizations led by women |

% of organizations led by men |

|

50% or less |

7 |

35 |

|

More than 50% |

93 |

65 |

N=218 crv = .350 p<.05

The Influence of Geography on New Brunswick’s Human Service Sector As many studies have highlighted, the charitable sector in Canada seems as diverse as the country itself. From province to province and from region to region, the charitable emphasis, level and nature of giving, challenges, and of course,

size of the sector, are highly varied. This section provides a brief overview of the regional and geographical data for the New Brunswick charitable human service sector. Particular emphasis is placed on the variations between rural and urban regions, an aspect of the sector that has not been widely studied. We begin by comparing the scope of service among Canadian, Atlantic, and New Brunswick organizations.

New Brunswick human service organizations tend to serve primarily their local area. This is similar to Canada as a whole, where the majority of voluntary organizations (64%) are local (i.e., they serve mainly the municipality or some other unincorporated local area in which they are located), and less than 10% serve outside of their province. The same holds true for the Atlantic Provinces, where 62% of organizations serve only their local region or municipality. According to the data in our survey, this trend is even more pronounced in New Brunswick, where 70% of organizations serve only local populations, and less than 5% serve populations outside of the province. New Brunswick nonprofits, then, are highly regionalized (possibly due to the rural nature of population distribution).

The majority of the charitable human service organizations in New Brunswick are located in rural areas and small towns. There are three urban centres in New Brunswick with populations of over 40,000 (Moncton, Fredericton, and Saint John). Just under half of the organizations that participated in our survey are located in these cities, while 55% are located in less densely populated areas. These figures correspond with the distribution of New Brunswick’s population, which, according to 2001 census data, is split evenly between rural and urban areas.11 Fifteen percent (15%) of responding organizations reported geography as a challenge of service provision, and 6% identified it as the primary challenge (most commonly expressed as “distance to patrons” and “covering of a wide service area with minimal resources and/or staff”). The rural location of organizations has been highlighted as a significant challenge in other provincial studies (Carr, Carr, Hanna, Rockwood, & Rodgers-Sturgeon, 2004) in which rural nonprofits have stated that isolation (in terms of training opportunities, connections to government, and the inability to be self-sufficient, etc.) limit the capacity of the organization.

A second issue, specific to the cultural geography of this province, is the increased challenges that come with isolation. Carr et al. (2004) have mentioned this in regard to the northeastern region in particular, which is predominantly Francophone and rural. Our survey data confirm that Francophone organizations are far more likely to be located outside of a major centre and therefore experience greater problems with geographical isolation in addition to potential linguistic barriers (see Table 16).

Table 16. Primary Language of Service Relative to Geographical Location

|

Primary language of majority of clients |

Organizations located in an urban centre (pop >40,000) |

Organizations located outside of an urban centre (pop. <40,000) |

|

English |

80% |

60% |

|

French |

5% |

33% |

|

Both |

14% |

7% |

|

Other |

1% |

0% |

N=256 crv=.354 p<.05

Urban organizations are more institutionally connected and serve wider areas. They are twice as likely to operate under, or be part of, an umbrella organization as those located in rural areas.12 They are also more likely to serve wider catchment areas (beyond their immediate location), suggesting that many rural areas are dependent on service providers in the three major centres.13 The average distance to farthest area served for urban organizations is 137km compared to 62km for rural organizations;14 this is not an unexpected result, since organizations serving the entire province are likely to locate their offices in one of the three cities (Moncton, Saint John, or Fredericton).

Rural and urban organizations tend to employ roughly equal numbers of staff on less than equal budgets. Organizations located in urban areas have significantly larger budgets, on average, than those in more rural regions. This difference is not significant, however, when we compare the number of paid staff, which suggests that rural organizations may be doing more with less or, at least, paying (almost) as many people with fewer dollars (see Table 17).

Table 17. Budget and Staff Size Relative to Geographical Location

|

Rural/Urban |

Average budget* |

Average staff size** |

|

Urban Center (pop >40,000) |

$845,202 |

19 |

|

Rural / Outside Urban Centre (pop <40,000) |

$491,432 |

15 |

*N=23 f=4.09 p,.05

*N= 237 f= .827 p=.364

Geographically speaking, the charitable sector in particular in New Brunswick has several distinct attributes. The large proportion of the population living in rural areas and its unique regional language specificity are two examples. The data emerging from this survey have highlighted the potential impact of these differences and raised some interesting questions about the capacity of rural organizations and about the capacity of urban-based organizations to support rural areas.

Discussion and Conclusion

To better inform public policy on the charitable human service sector in New Brunswick, we need to have a clearer view of it. This study has made some contribution in this regard by establishing that the sector tends to offer services to the general population rather than to select interest groups. It has pointed out that these services have been offered for a long time by organizations that are diversified and vary widely in size. These organizations are generally seriously lacking funding, and this is probably one of the factors contributing to their difficulty in finding and retaining staff and volunteers.

Findings on the challenges of service provision show that, within the same shifting political and social climate, charitable organizations in New Brunswick are struggling with many of the same challenges as those in other provinces. Much like charitable human service organizations in the rest of Canada, New Brunswick organizations tend to engage most commonly in social service activities, rely heavily on volunteers, and draw their human resources strength primarily from women. New Brunswick’s charitable sector is also somewhat unique in that organizations tend to be well established and to serve a wider public rather than operating with a membership structure. Funding is the single most important challenge facing these charities. This is an alarming though not surprising trend, which is supported by most of the literature on the voluntary sector. The immediacy of this challenge, however, should not overshadow the fact that the struggle for human resources is also significant, even among large, well-funded organizations. Together, these two challenges point to a struggle for sustainability, both within organizations and for the sector as a whole. This section examines how organizations govern and manage themselves within this climate.

Our research has shown that New Brunswick human service organizations are faring better, on some fronts, than the Canadian sector as a whole. While most New Brunswick human service organizations do not rely on government for the majority of their funding, nevertheless a large proportion of their funding comes from government sources. This is particularly true for large organizations. These organizations are facing significantly different reporting and funder challenges than are organizations that are not primarily reliant on government dollars. The nature of the relationship between government funding bodies and the voluntary sector organizations that depend on them are well documented (see Scott, 2003; Gumulka et al., 2006), and there have been some efforts to tackle this issue at the policy level. For example, in 2001 the Voluntary Sector Initiative (VSI) produced the joint policy document, An Accord Between the Government of Canada and the Voluntary Sector, which included a Code of Good Practice on Funding. The code aims at both increased accountability and more strategic and stable funding practices. More recently, the Voluntary Sector Forum was designed to bring the concerns of voluntary agencies to the fore. The ground-level change from these policies is not well documented, however, and the current results from this study (as well as those of Scott, 2003) suggest that the problems are persistent.

On the gender front, it is clear from the results of our survey that the voluntary sector in New Brunswick, like that of the rest of Canada, is composed primarily of women. However, results also show some trends of inequity within the hierarchy of the sector. Other reports have also pointed to the predominance of women in the sector as a manifestation of inequity, given the sector’s tendency to demand high education and skills in return for pay and stability that is often lower than that of other sectors (Mailloux, Horak, & Godin, 2002; Carr et al., 2004; Thériault, 2003). One other provincial study has also identified a concern that women may begin leaving the sector as funding becomes increasingly less stable (Carr et al., 2004). Others predict the possibility of an employment crisis for the sector, which clearly relies on women as the backbone of its workforce, if it fails to respond to the needs of women in terms of equal pay, stability, and benefits (McMullen & Schellenberg, 2002).

New Brunswick human service organizations are also concerned by issues of accountability, not only toward their government funders, but toward their clients as well. They are active in evaluating their services. Moreover, they are generally capable of coping with the reporting requirements imposed on them. Overall, therefore, these are organizations that government can feel comfortable doing business with; indeed, that is what is happening, as governments are the main source of funding for the sector.

Most New Brunswick human service organizations, however, operate with small budgets that limit the scope of their activities and their geographic reach. Realistically, we cannot expect too much from this sector, which is in dire need of additional resources. The question is, therefore, not whether the state will continue to collaborate in service delivery in some form with the many charitable organizations of the province, but whether the state is ready to enter into a true partnership with these agencies to allow them to improve and expend the benefits they provide to the people of New Brunswick. In sum, will we see an evolution in public policy in the province towards this sector? Recently (in September 2007), Premier Shawn Graham received the recommendations of a Community Non-Profit Task Force led by Claudette Bradshaw. The implementation by the government of these recommendations should bring a clearer view of what the future might hold for charitable human service organizations in New Brunswick and for the nonprofit sector in the province as a whole.

REFERENCES

Beveridge, W. (1942). Social insurance and allied services. London: H.M.S.O.

Bugg, G., & Dallhoff, S. (2006). National study of board governance practices in the nonprofit and voluntary sector in Canada. Ottawa: Strategic Leverage Partners Inc. and the Centre for Voluntary Sector Research and Development.

Canada Revenue Agency. (2001). Registering a charity for income tax purpos—es. Ottawa: Charities Directorate. <http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/E/pub/tg/t4063/ t4063–01e.pdf>.

Canada Revenue Agency. (2001). Charities Directorate searchable database. <http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/tax/charities/menu-e.html>.

Carr, A., Carr, K., Hanna, N., Rockwood, P., & Rodgers-Sturgeon, K. (2004).

Employment in the voluntary sector: The New Brunswick context. Fredericton, NB: New Brunswick Department of Training Employment and Development.

Community Foundations of Canada and United Way of Canada. (2004). What we heard: Findings from discussions in communities about a voluntary sector human resources council. Ottawa: Author.

Dow, W. (2001). Backgrounder on the literature on (paid) human resources in the Canadian voluntary sector. Ottawa: Voluntary Sector Initiative.

Gumulka, G., Hay, S., & Lasby, D. (2006). Building blocks for strong communities: A profile of smalland medium-sized organizations in Canada. Ottawa: Imagine Canada and Canadian Policy Research Networks.

Guo, C. (2004). When government becomes the principal philanthropist: The effect of public funding on patterns of nonprofit governance. Arizona State University: Center for Nonprofit Leadership and Management College of Public Programs.

Hall, M., Andrukow, A., Barr, C., Brock, K., deWit, M., Embuldeniya, D., Jolin, L., Lasby, D., et al. (2003). The capacity to serve: A qualitative study of the challenges facing Canada’s nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

Hall, M., deWit, M., Lasby, D., McIver, D., Johnson, C., McAuley, J., et al. (2004).

Cornerstones of community: Highlights of the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations. no. 61–533. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Hall, M., Phillips, S., Meillat, C., & Pickering, D. (2003). Assessing performance: Evaluation practices & perspectives in Canada’s voluntary sector. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

Mailloux, L., Horak, H., & Godin, C. (2002). Motivation at the margins: Gender issues in the Canadian voluntary sector. Ottawa: The Voluntary Sector Initiative Secretariat.

Marsh, L. (1943). Report on social security for Canada. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press [1975].

McMullen, K., & Schellenberg, G. (2002). Mapping the nonprofit sector. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks (CPRN).

Pay Equity Task Force. (2004). Pay equity: A new approach to a fundamental right. Pay Equity Task Force Final Report. Ottawa: Ministry of Justice and Attorney General of Canada,

Prince, M. (1988). Volunteers in social service organizations. National Survey on Volunteer Activity, profile 8. no. 89M0011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Rowe, P. M. (2006). The nonprofit and voluntary sector in Atlantic Canada: Regional highlights from the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations. Toronto: Imagine Canada.

Scott, K. (2003). Funding matters: The impact of Canada’s new funding regime on nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development.

Sharpe, D. (2001). The Canadian Charitable Sector: An Overview. In J. Phillips, B. Chapman, & D. Stevens (Eds.), Between State and Market (pp.18–19). Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Statistics Canada (2004). Satellite account of nonprofit institutions and volunteering. no. 13–015-X1E. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Statistics Canada (2006, December 8). Satellite account of nonprofit institutions and volunteering: 19972003. In The Daily. <http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/ English/061208/d061208a.htm>.

Thériault, L. (2003). Issues of compensation in the volunteer sector. The Philanthropist, 18(2), 109–120.

Voluntary Sector Initiative. (2002). An accord between the government of Canada and the voluntary sector. Ottawa: National Library of Canada.

NOTES

1 Recreation clubs and church congregations were excluded from our study, unless they were shown to be providing health or welfare related services (i.e., soup kitchens, etc.). While primary care hospitals were excluded from the sample, ambulatory care and fire service organizations, clinics, nursing homes, and hospital auxiliaries were included.

2. Two key differences are: 1) the NSNVO study sampled organizations from all sectors, and 2) NSNVO included not only registered charities, but incorporated nonprofit organizations as well, thereby including organizations that primarily serve private needs rather than the public at large (Hall et al., 2004, p. 64).

3. See, for instance, Thériault, L. (2003). Issues of Compensation in the Volunteer Sector,

The Philanthropist, vol. 18, no. 2: 109–120.

4. See: Bugg & Dallhoff, 2006; Gumulka et al., 2006; Hall et al., 2003; Guo, 2004.

5. This question was posed as a five point scale, where 1 = “no input considered” from that group and 5 = “completely determined” by that group. For ease of reporting, results have been condensed into high (4–5), medium (3) and low (1–2) levels of input.

6. While our data seems to point to a more frequent use of evaluation practices among our sample organizations compared to national studies, there is a large variation in terms of how often evaluations are conducted and what is measured; therefore, study results may not be directly comparable.

7. In Hall et al. (2004, p.15), social service organizations receive the highest share of revenues if we limit the comparison to the categories included in this New Brunswick study (health, social services, development and housing, law and advocacy, grant-making and volunteerism support, and other).

8. Scott (2003) explains mission drift in the following way: “The emerging funding regime is calling into question how nonprofit and voluntary organizations define their mission and programs, how they structure themselves, and generate the resources necessary to sustain their activities. Many worry that organizations are being driven to take on programs or activities that dilute their missions, stretch their resources and erode their base of legitimacy.” (p.150).

9. In our New Brunswick survey, the question of mission drift is asked on a 5-point scale, while in Scott’s survey (2003), results are derived from a yes/no question on the subject; therefore, it is unrealistic to make a direct comparison of the data.

10. Though not statistically significant, the same pattern (the higher the budget, the higher the male-to-female ratio) is seen in the data when we compare budget size to the gender of the managers.

11. Source: Statistics Canada population tables: “Population urban and rural, by province and territory.” Results are not directly comparable, as this table defines the rural/urban split according to population density (over 400 persons per km2).

12. Cross-tabulation (crv=.208, p<.05).

13. Cross tabulation (crv=.297, p<.05) shows 43% of urban based and 16% of rural-based organizations serve areas beyond their immediate municipality/area (ie: a sub-provincial region or larger).

14. Comparison of means (f= 29.34, p>.05)

LUC THéRIAULT, PH.D., HEATHER MCTIERNAN, M.PHIL., AND CARMEN GILL, PH.D.*

University of New Brunswick

Luc Thériault, Ph.D. (University of Toronto), is Associate Professor of Sociology, University of New Brunswick, and has expertise is social policy and third sector studies, with a focus on the interactions between governments and social economy organizations involved in the delivery of human services. Heather McTiernan, M.Phil. (University of New Brunswick), is Program Coordinator/Research Assistant, University of New Brunswick, and has a background in both environmental and social policy research. Carmen Gill, Ph.D. (Université du Québec à Montréal), is Associate Professor of Sociology/Director, Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research, University of New Brunswick, and has expertise in the fields of family, social policy, third sector studies, and violence against women. Dr. Scott Bell from Brown University and Dr. James Randall from UNBC have collaborated on this research. The financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for this project is gratefully acknowledged.