Introduction

There is a considerable, albeit inconclusive, literature on whether workers in the nonprofit sector are paid less than their counterparts in the private and public sectors. For example, a large national study in the U.S. showed positive and negative differentials for some occupations and industries, but no systematic differences that are sector wide (Leete, 2000). Other studies targeted to specific sub-sectors are mixed in their results: many support these negative wage differentials but others do not (Bond, Raehl, & Pitterle, 1999; Naci Mocan & Tekin, 2003; Naci Mocan & Viola, 1997; Preston, 1989; Shahpoori & Smith, 2005).

In comparing the wages offered by for-profit firms and nonprofit organizations, it is helpful to note at the outset that nonprofits often have greater financial restraints than their counterparts in the for-profit sector and, hence, may offer lower wages. But the reverse may also be possible: for-profit firms that are subject to market discipline and responsibility to shareholders may have less scope to offer higher wages to workers. Thus it is not evident, prima facia, whether nonprofits or for-profits, would offer higher wages.

Despite the lack of unambiguous evidence for negative wage differentials, nonprofit workers often perceive themselves as underpaid compared to their counterparts in other sectors. A recent survey conducted by the Brookings Institution (Light, 2003) found that nearly half of all paid nonprofit workers in the human services believe they could make more money elsewhere, but they see themselves as driven by mission not money. Another survey reported that current nonprofit executives across all sectors in the U.S. believe that they could have made more money working in another sector (Bell, Moyers, & Wolfred, 2006).

Career counsellors and executive placement centres publicize the negative wage differential. For example, a prestigious business school in the U.S. offers financial aid to those students choosing to work in the nonprofit sector because “students are interested in public service careers, but their educational debt burden may inhibit them from pursuing these jobs since they tend to provide lower compensation than the for-profit sector” (Almanac, 2005, p. 2).

Perpetuating the perception of lower wages are several leading websites focused on nonprofit employment. They explicitly inform individuals searching for employment that nonprofit salaries are lower than those in other sectors on average.1 Lynda Ford, a human-resources consultant, maintains that nonprofits offer lower salaries because they compensate employees by creating a good work environment (Klineman, 2004). Furthermore, the hue and cry in the media about some excessive nonprofit salaries2 has given rise to a tendency to lower executive salaries in the nonprofit sector. In the last few years, federal agencies in the U.S.3 and Canada are also paying greater attention and giving more scrutiny to executive compensation in the nonprofit sector.

Against this background, in this research we examine the perceptions of executive directors in Canadian nonprofits regarding wage differentials in the nonprofit sector compared to the for-profit sector. These perceptions, especially concerning their own wages, are important because it is in this context that executive directors make choices about where to work. This, in turn, determines the managerial labor supply for the sector. We first present a brief review of the theoretical explanations offered by scholars for wage differentials. We then turn to the empirical findings on wage differentials before presenting our findings.

Literature Review

The first theoretical explanation of lower wages in the nonprofit sector is that the difference may be considered as a labour donation by the employee to the nonprofit. Nonprofit workers attracted to the mission of their organization are willing to accept lower wages because they see their forgone wages as a donation toward a cause they support. This idea was introduced by Preston (1989), who suggests that workers are willing to trade off lower wages against the social benefits that the nonprofit provides. An extreme case of such a donation is volunteer labour.

This line of argument was also emphasized by Hansmann (1980). He argued that nonprofits, because they are subject to a non-distribution constraint (no individuals can appropriate any surplus generated), may be able to attract precisely the kinds of employees who are willing to make the labour donations suggested by Preston (1989). Those employees are willing to work for less than they might otherwise get because they see any surplus generated by the organization as going back into promoting the mission of the organization. Indeed, there is some evidence that managers and professionals working for nonprofits differ significantly in their motivations—for example, Young (1983) shows that managers of nonprofits have a strong commitment to the philosophy of the nonprofit organization as fulfilling a social rather than a business need. Mirvis and Hackett (1983) also assert that an important difference between for-profit and nonprofit managers is their attitude toward the goals of the nonprofit since ‘‘the latter bring to their jobs a greater commitment and non-monetary orientation’’ (p. 10).

Eckel and Steinberg (1994) posit that nonprofit managers have utility functions that include perks, public goods, and income. They argue that, because potential managers differ in their marginal rate of substitution between perks and public goods, policies to encourage the selection of managers with preference for public goods over perks and income would result in better managers. Handy and Katz (1998) elaborate on this point and suggest that such a positive self-selection among managers is possible when lower monetary wages are combined with institution-specific fringe benefits—a form of non-monetary compensation. These include job characteristics such as higher levels of autonomy, opportunities to develop skills, work flexibility, job tenure, etc. They argue that this bundle of monetary and non-monetary compensation would have to be competitive to attract highly motivated and competent managers.

Employees in nonprofits are viewed as intrinsically motivated by the organization’s values and mission. They derive their satisfaction from work rather than just wages (Steinberg, 1990). Examining job satisfaction measures from the U.S. and Great Britain over the 1990s, Benz (2005) finds that nonprofit workers were generally more satisfied with their jobs than for-profit workers, a finding that is explained by intrinsic work benefits.

Another possible explanation for disparity in compensation between the nonprofit and for-profit sectors may be ‘compensating wage differentials’ (Weisbrod, 1983). Lower wages are acceptable to nonprofit workers because there are compensating job characteristics that make up for the lower pay—for example, family-supportive policies, a more egalitarian workplace, flexibility in work schedules, greater job stability, more control over the work performed, building a reputation for a public career, and not working toward a financial bottom line.

Frank (1996) found that the wages individuals are willing to accept are lower in nonprofits than for-profits, and this also lends credence to such compensating wage differentials. Jeavons (1994) adds to this by proposing that nonprofit workers accept lower wages because they enjoy the values of the organization and are treated in a style consistent with these values.

Social expectations also play a role in keeping wages lower in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit wages that rival those in the for-profit world may be unacceptable given that many of these organizations have to appeal to donors to help support them (Mason, 1996). Donors may eschew nonprofits if they perceive their donations are being diverted to meet excessive demands of managerial compensation. Furthermore, lower wages earned in a nonprofit are less detrimental to the individual’s social status than a low managerial income earned in a for-profit; the latter may be seen as reflective of the person’s productivity, while the former may be interpreted as a labor donation to the nonprofit.

These explanations support the negative differences in the wages between the sectors but cannot account for the studies that show no differences in wages or, even more so, those that show positive wage differentials in nonprofit organizations compared to for-profits. Positive wage differentials in the nonprofit sector may occur if nonprofit organizations behave as ‘for-profits in disguise’ (Weisbrod, 1988). In other words, due to the lack of incentives to minimize costs and maximize profits, they pursue the private interests of managers and directors and disburse the surplus generated in the form of increased wages. This is a propertyrights approach, and its incidence is explained by Weisbrod (1988, p.11) as follows: “Disguising a distribution of profit by calling it a wage payment is illegal, but given the costs of enforcement, excess payments to managers as well as to firms associated with trustees of the non-profits can go undetected.”

Empirical Studies

Although theoretical explanations for negative wage differentials are more persuasive, they are found to be negative or positive depending on the sub-sector studied or employment status: managers and executives versus service providers and blue collar workers.For example, using data from a 1979 census survey and a 1980 survey of job characteristics, Preston (1989) analyzed the wage differentials for employees in the for-profit and nonprofit sectors in the United States. Controlling for human capital, demographic structure, occupation, and flexibility and rigidity of work schedules, she finds a negative wage differential of 20% for managers and professionals but no significant difference among clerical employees. The differential is especially robust for nonprofits involved in the provision of social services and arts and culture. Several other studies also indicate that lower wages are paid for certain managerial occupations in the nonprofit sector compared with those in the for-profit sector (Ball, 1992; Emanuele, 1997; Mirvis & Hackett, 1983; Preston, 1988; Roomkin & Weisbrod, 1999; Shackett & Trapani, 1987) Weisbrod (1983) found that public interest lawyers are paid considerably less compared to those who choose corporate jobs and suggests that the former have different “preferences.” These preferences account for the public interest lawyers’ willingness to accept lower monetary rewards for public interest work.4 In a similar vein, Frank (1996) reports on an employment survey done at Cornell University indicating that Cornell graduates employed in the for-profit sector earned 59% more on average than those employed in the nonprofit sector, after controlling for employee variations based on gender, choice of curriculum, and academic performance. Johnston and Rudney (1987) found the average annual earnings differential of nonprofit employees in service industries to be more than 20% lower. A study looking at full-time pharmacist salary costs found lower salaries in nonprofit hospitals compared to other sectors (Bond et al., 1999). Negative wage differentials in the nonprofit sector are not limited to the U.S. Using the French Labour Force Survey over 1994–2001, Lanfranchi and Mathieu (2005) find an average wage differential of 22.6% in favour of the for-profit sector.

Other studies, however, show positive wage differentials. For example, Holtmann and Idson (1993) found a slight wage premium for nurses in nonprofit institutions in comparison to other sectors, although “tenure in the present job is rewarded more in the nonprofit sector than in the for-profit sector” (Holtmann & Idson, 1993, p.69), suggesting the importance of non-wage benefits. Leete (2000), using a large database of the 1990 U.S. census, found no systematic nonprofit wage differential. Her study included all sub-sectors and managerial and non-managerial wages. Mocan and Viola (1997), using more stringent controls, also found no significant nonprofit wage differential amongst childcare workers.

Using a monthly survey of households conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Census, Ruhm and Borkoski (2003) found that the lower wage in nonprofits all but disappears when hours and workplace characteristics are taken into account, confirming the compensating wage differential explanation that nonprofits provide better environments and demand fewer hours from their employees. However, a study by Emanuele and Higgins (2000) calls into question the compensating wage differentials theory. They found that nonprofits were less likely than forprofits to offer benefits (health insurance, retirement and pension plans, on-site childcare, paid holidays, personal and parental leave, or salary equity).

Preston (1988) estimates wage differences in the day care industry and finds that the nonprofit differential is significantly positive and ranges from 5% to 10%. Similarly, the empirical evidence presented by Borjas, Frech, and Ginsburg (1983) shows that profit-maximizing nursing homes pay the lowest wage rates as compared to other types. The July 2003 National Compensation Survey in the U.S. found that wages for workers in for-profit hospitals were lower than the wages of workers in nonprofit hospitals; however, earnings for teachers of college and university were nearly identical in for-profit and nonprofit universities (Shahpoori & Smith, 2005). These studies, which find nonprofit wage differential to be positive, support a property rights explanation, which suggests that higher wages in nonprofits result from the weaker incentives for cost minimization due to the lack of a profit maximization motive.

Given these mixed data and varying theoretical explanations, it is essential to understand what senior management perceive as the wage differential, if any. Boards of trustees and senior management are often involved in wage-setting decisions, and if they perceive wages in the nonprofit sector to be less than those in other sectors, this would influence what wage offers are made and may in turn sustain such wage differentials, especially in the areas where nonprofits are not competitive. Wage perceptions would also influence the supply of workers seeking managerial jobs in the sector.

Methodology

To determine whether a perception of lower wages exists among those who work at the upper managerial levels in nonprofits, we surveyed executive directors (or their equivalents) of nonprofit organizations across Canada during the period September 7 to November 24, 2005. We asked them their perspectives on wages and what they might have made in the for-profit sector in comparable jobs. In addition, we asked why they choose to work in the nonprofit sector. To create a sampling frame, we used Associations Canada 2002, an annual directory of Canadian nonprofit organizations. We e-mailed a request to participate in an online survey to 4,552 nonprofits with valid e-mail addresses and received responses from 785 organizations. Given that this was part of a relatively long online survey on organizational characteristics, volunteer labour, wages, and benefits, this is a low but acceptable response rate of 17%. Of the total respondents, only 377 organizations responded with information on executive directors’ wages; we used this subset as the sample for this research.

Findings

1. Nonprofit Characteristics

The 377 organizations were involved in a variety of activities including social services (23%), arts and culture (16%), sports and recreation (13%), education and training (11%), health care (7%), environment (5%), and other (22%). These organizations had been in existence for between one and 165 years and had an average age of 37.9 years. Annual revenues averaged $2 million, with 14% of organizations reporting annual revenues of less than $100,000. Furthermore, 28% of organizations had revenue in excess of $1 million; this includes 8% with revenues in excess of $5 million and 4% with revenues in excess of $10 million.

2. Executive Directors

Respondents were mostly female (68%) and ranged in age from 24 to 79, with an average age of 48.5. Eighty-two percent were born in Canada, and those that had immigrated to Canada had done so anywhere from six to 62 years ago, with the average being nearly 33 years. The average length of time they had been in their current position was six years, but length of tenure ranged from less than one year to 55 years. On average, these executive directors had worked in the nonprofit sector for 13.6 years. They were well educated; 68% had university degrees and, of that group, nearly 27% had post-graduate training or professional degrees. In spite of this training, the average salary was $51,400 with 61% of the executive directors earning under $45,000.

3. Wage Differentials

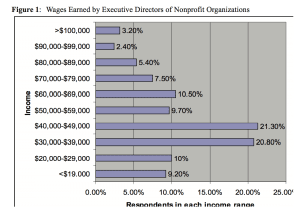

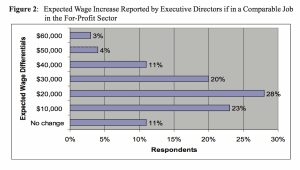

Given our earlier discussion on wage differentials, we asked executive directors if, in general, wages in the nonprofit sector were higher, the same, or lower than those in the for-profit sector. Surprisingly, nearly a quarter responded that they did not know; of those that did answer, most responded that wages in the nonprofit sector were either lower (56%) or the same (35%) as the for-profit sector, while few (9%) believed they were higher in the nonprofit sector. Subsequently, we asked the executive directors specifically about their own wages and how much they would expect to earn if they were working in a similar capacity in a for-profit organization. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present wages earned by executive directors and the earnings they would expect for doing similar work in a forprofit organization.

Figure 1: Wages Earned by Executive Directors of Nonprofit Organizations

Only 11% of respondents viewed their current wage on a par with what they would expect to make in comparable jobs in the for-profit organization, while 89% regarded their wages as at least $10,000 lower (see Figure 2). Indeed, no one expected to make less by moving to a comparable job in the for-profit sector.

Figure 2: Expected Wage Increase Reported by Executive Directors if in a Comparable Job in the For-Profit Sector

Thus, most respondents expected much higher wages—an average of $22,600— if they were to work in the for-profit sector. Executive directors were cognizant of the wage differentials but had for the most part voluntarily chosen to work in the nonprofit sector at lower wages.

We next investigated if the perceived wage differential by executive directors was a function of organizational characteristics. In other words, are executive directors of larger nonprofits more likely to perceive smaller differences in their wage differentials?

Our hypothesis was that larger organizations (i.e., those with more revenue) would be well-established (i.e., older), have greater number of paid staff (number of employees) and could afford to pay executive directors higher wages because they have to compete in the labour market for talented individuals who have to take on greater responsibilities and manage larger staff and more complex organizations. Thus it seemed likely that salaries of executive directors of larger nonprofits would be more in line with the market and that if they did perceive negative wage differentials, these differentials would be lower than those of executive directors working for smaller nonprofits.

Our findings confirm these hypotheses. We find positive and significant correlations between size of the organization (measured by the organization’s total annual revenue) and its age (r = .267, p<.001) and number of employees (r = .506, p<.001). We also find, in line with our hypothesis, a negative and significant correlation between the size of the organization and the perceived wage differential (r = -.108, p<.05), implying that the larger the organization and the longer it had been in existence, the more likely executive directors of these organizations were to perceive that their salaries were in line with salaries for comparable positions in the for-profit sector. Thus, executive directors in larger nonprofits perceive that they would make smaller gains if they were to work in comparable for-profits than do executive directors who work for smaller nonprofits. The latter perceive that there are larger gains to be made by moving to comparable jobs in the for-profit sector.

To see if the combined effects of organizational variables and personal characteristics explain perceived wage differentials, we performed a linear regression analysis in which the perceived wage differential is the dependent variable and various organizational characteristics—age and size of the organization, length of work week—and personal characteristics—the respondent’s age, education, gender, and time in current position—are the independent variables.

The regression was a poor fit (R2= 10.8%), but the overall relationship was significant (F8, 315 = 4.641, p = 0.000). Wage differentials perceived by executive directors were significantly negatively related to the organization’s size (t =-2.441, p <.05) and positively related to the hours worked by the executive director (t = 2.304, p <.05). Furthermore, more educated executive directors perceived higher wage differentials (t = 3.951, p <.001). These findings suggest that the perception of negative wage differentials is greatest for those highly educated executive directors working long hours and this particularly true for those working in small nonprofits.

4. Self-Selection: Altruistic Behaviours

As seen earlier, the literature suggests that there is some self-selection of individuals choosing to work in the nonprofit sector: some individuals who work in the sector appear to be more committed to the mission of the organization and are prepared to forfeit monetary wages in lieu of work satisfaction. If there is such self-selection, we might speculate that these individuals are more public spirited or altruistic in their behaviour. One measure of this may be their giving behaviours, not only in terms of money, as seen in taking lower wages, but also giving of their time. To test this, we asked the respondents in our survey if they had volunteered in the past 12 months. Eighty percent responded that they had volunteered and reported that they had volunteered 11 hours a week on average. This compares very favourably to the national estimate of 27% of Canadians who volunteer an average of 3.1 hours per week (McKeown, McIver, Moreton, & Rotondo, 2004).

Although this is not definitive in suggesting that public-spirited individuals are attracted to nonprofits, this finding may imply that, along this one dimension of volunteer behaviour, executive directors in our sample are different from the average Canadian. Combined with the finding that nonprofit executive directors believe that they can make more money in the for-profit sector but have deliberately chosen their current jobs, this suggests that their choice is not motivated by monetary wages only. In the next section we therefore examine what motivates them to work in their current jobs.

5. Motivations for Working in the Nonprofit Sector

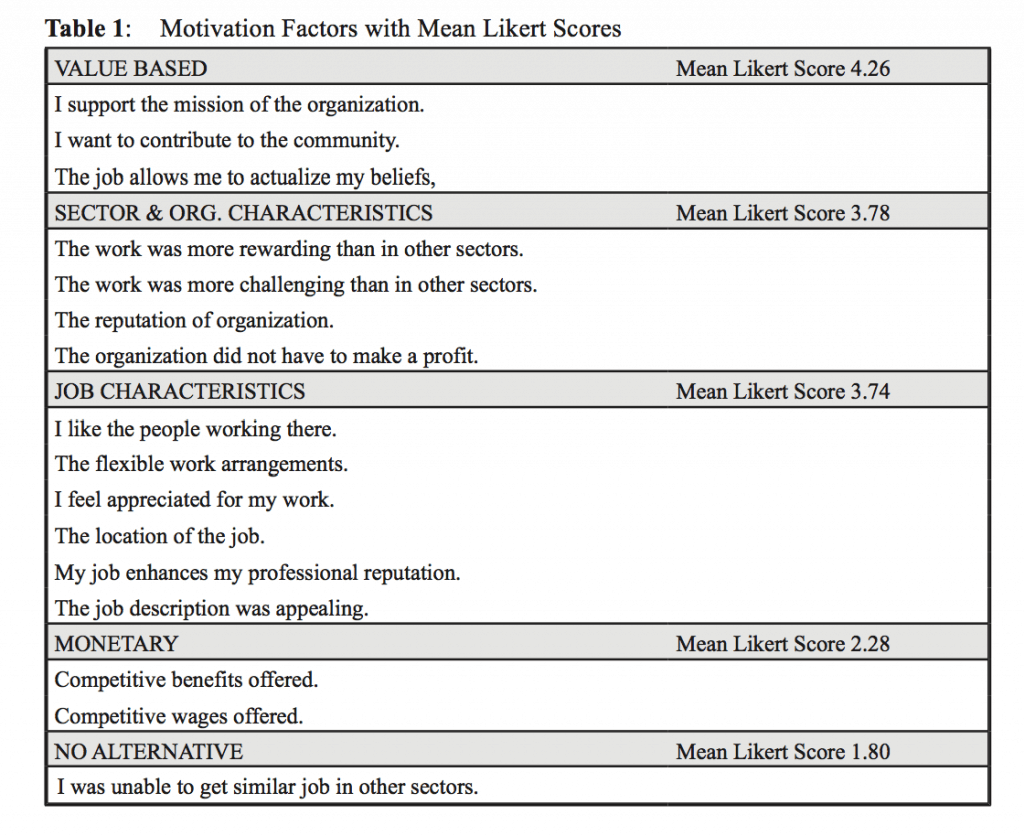

Given that the majority of executive directors believed they could do better by working in the for-profit sector, we examined their motivations for choosing the nonprofit sector. To do that, we presented them a list of 16 possible reasons for choosing (or staying in) their current jobs and asked them to rate these items on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating the highest degree of disagreement with the statement presented and 5 indicating the highest degree of agreement.

For our analysis, we grouped the 16 statements into five motivational factors based on substantive content: 1) motivations related to personal values of the respondents, 2) motivations based on the characteristics of the sector and the organization in which they work, 3) their particular job characteristics, 4) the monetary compensation of wages and benefits, and, 5) the lack of available alternative jobs. Table 1 lists the various motivations and provides means of the Likert scale scores for each of the five factors.

Table 1: Motivation Factors with Mean Likert Scores

We find that the factor that produced the highest score of agreement (4.26 out of 5) was based on individual’s values and the desire to contribute to their community. This finding replicates many studies that suggest that there is a self-selection of individuals into the nonprofit sector who tend to actualize their values by working for organizations whose goals are in line with their values; those who tread the moral high ground, as suggested by Frank (1996). Motives related to monetary rewards, by comparison, had a low score, suggesting that most executive directors were not in their jobs because of competitive wages or benefits; indeed, many believed they could do monetarily better elsewhere. These findings support the labour donation theory in explaining the prevalence of lower wages in the nonprofit sector.

Sector and job characteristics are also important motives for why executive directors chose their jobs, suggesting that while they may have done better in comparable jobs in the for-profit sector, there are compensating wage differentials that made up for this loss. There was least agreement with the motive that suggested that executive directors were working in the nonprofit sector because they could not find comparable jobs in the for-profit or public sector. Most executive directors (92%) disagreed with this statement; they deliberately chose to work for nonprofits despite the wage penalty.

6. Gender Differences

Although we know that more women work in the nonprofit sector in general (McMullen & Schellenberg, 2002), which may explain the higher proportion of women (68%) in our sample, we do not know if their perceptions of wage differences or reasons for choosing to work in the sector differ from men. In our sample, men were slightly older and more educated, and they had worked a little longer at their current jobs, but none of these differences were statistically significant. However, the men earned more than the women—an average of $19,600, a 30% difference that is statistically significant (t = -5.928, p<.001). This finding replicates trends in the U.S. where the pay gap between male and female senior executives was 25.6% in 2005 (Lipman, 2006). A similar study in 2002 (Jones, 2003) found that female chief executive officers earned 31.5% less than their male counterparts. Earlier, in 2001, Guidestar, using a national database on U.S. nonprofits, found a much higher gender disparity of nearly 50% among chief executives (Lewin, 2001). In our sample, even though men earned nearly a third more than women, their perception of wage discrepancy was slightly higher than for women. This difference, however, was not statistically significant, suggesting that perceptions of wage differentials were not explained by levels of current salaries. The findings suggest that men and women are equally willing to give up significant monetary benefits to work in nonprofits, although men earn significantly more than women.

Given this difference, we next examine if there is an underlying gender difference among the motivation factors that may explain why women tend to accept lower salaries to work in nonprofits than do men. To do so, we did a t-test to see if the means (of the Likert scale scores) of the motivation factors differ significantly for men and women. We found that there were no significant differences across gender for the value-based motivations or those related to the sector characteristics. In other words, both men and women were equally motivated by their values to work in nonprofits and take the financial penalty.

However, we did find that women were significantly more likely than men to choose their jobs because of the job characteristics (t= -2.110, p<.05) but significantly less likely than men to respond to monetary motivations (t=3.076, p<.001). This suggests two explanations: either salary offers made to men are higher or men were better at negotiating higher salaries, which may explain the earlier finding that men earn significantly more than women. Finally, there were no statistically significant differences among men and women on the question of whether they chose a job in the nonprofit sector because they were unable to get a comparable job in the other sectors; both men and women’s Likert score on this motivational factor was low.

7. Benefits and Challenges of Working in Nonprofits

The last section of the online survey provided a space the respondents to add comments on the benefits and challenges in working in the nonprofit sector. The comments add depth and colour to the numbers discussed earlier. Five themes regarding the benefits of working for nonprofits arise from the comments provided: 1) the advantage of working in value-based organizations and being able to make a positive contribution to the community; 2) the diversity and flexibility of the job; 3) skills training provided in their jobs; 4) the sense of satisfaction and accomplishments; and 5) the ability to influence change in the environment. We reproduce a sample of comments in Table 2.

These comments augment the earlier findings that suggest that much of the appeal of working in the sector is not motivated by pecuniary gains. While most executive directors believed they would do much better in terms of salary in the for-profit sector, their primary motivation in working for the nonprofit sector is their desire to contribute to their communities or work for causes they believed in. This motivation ties in with the theoretical explanation of lower wages being a labour donation of nonprofit workers to the cause they espouse. Furthermore, the many comments on the characteristics of the sector and the particularities of their jobs also give support to the theoretical explanation of compensating wage differential; nonprofit executive directors are trading off monetary gains for better work environment, autonomy, flexibility, and an opportunity to actualize their values

Although executive directors were cognizant of the benefits of working for the nonprofit sector, they were also acutely aware of the challenges. A preponderance of the comments on the challenges of working in nonprofits was related to lack of funding and budget constraints facing them as they struggled to achieve the goals of the organizations. Other comments included working with volunteer boards, recruiting volunteers and low wages and few benefits. Despite these significant challenges and lower wages most executive directors deliberately choose to work for nonprofits. The benefits of working for nonprofits appeared to outweigh the low wages, lack of resources, challenges of obtaining funding, and dealing with volunteers and volunteer boards. We reproduce a sample of comments in Table 3.

Table 2: Responses to Open-Ended Questions on the Benefits of Working for a

Nonprofit Organization

• I believe individuals who work for not-for-profit organizations are not working for the wage, but rather because of their personal commitment to the specific organization. Their reward is not monetary, but may be more “spiritual” in nature. It reinforces my core beliefs in working to improve society. I can work with like-minded individuals.

• Working within a non-profit environment allows a much broader impact within the community. The arts are about contributing to the community and my job allows me to be part of that contribution.

• I am not overtly contributing to the perpetuation of an economic system that I fundamentally disagree with (i.e., capitalism). In addition, I am making a positive contribution to society and in the case of this particular nonprofit.

• Self-satisfaction. It is very important to me to be able to work in a job I love. I have for many years worked for in a position with higher wages and benefits during my child raising years. It is very nice to work in a position where I can find great personal satisfaction.

• The ability to influence positive change for individuals with a disability.

• No bureaucracy compared to the government and there is more work-life balance than in the private sector

• High level of job satisfaction: challenging in that it requires all my skills and the job is different every day.

• Personal growth and development of wide range of skills; giving back to an organization that meant very much to me as a youth; developing friendships both locally and nationally.

• Accomplishing my personal life goals and being a part of an organization that shares those goals.

• Freedom to grow and gain a vast amount of knowledge regarding all aspects of how a not-for-profit works

• I have more freedom to establish priorities, create solutions, and implement change and vision.

• The dynamic and energized people that want to contribute to sport in a meaningful way. I can be creative and implement new projects constantly that benefit the organization. The volunteers and staff that I work with have a passion for the sport.

• Autonomy of leadership; a softer work environment.

• Flexible time while having young school age children at home. It allowed me not to put them in day care. The versatility of the different things I have to do.

• Sense of self-satisfaction, working in the not-for-profit sector allows me to be authentic as a person and validates my social concerns.

• Flexibility to maintain home/work balance and flexibility to create and develop projects. I am able to use all my skills: creativity, PR, administration.

• Work with a lot of autonomy, provide a positive role model for my child, and work close to home.

• Have worked senior management for many years in for-profit sector. Too much work and too little appreciation. Even though this job has too many hours and too little pay, I still prefer it here!

Conclusion

Our research, suggests that most executive directors working in nonprofits believe they are underpaid but choose to continue to work for reasons that are value-based and because they find certain job characteristics appealing. In particular, more than half our respondents tell us that there exists a negative wage differential in general across the nonprofit sector as compared to the for-profit sector. Most executive directors expect to make more money if they worked in comparable jobs in the for-profit sector. This suggests that at the senior management level, the perceived negative wage differential is even more pronounced.

Understandably, as these are self-reported findings, it can be argued that these perceptions of wage differentials may not be grounded in reality. However, individual perceptions are the basis on which choices are made, so although the earning expectations may be contestable in absolute terms, the magnitude of the findings is striking. This, combined with the qualitative responses, suggests that for nine out of ten executive directors, the average wage penalty of $22,600 is a significant price they are willing to pay for the benefits they receive in working for nonprofits.

Our qualitative findings on motivations for working in nonprofit organizations show that respondents hold strong preferences about working in the nonprofit sector. They chose to work in this sector because they wanted to contribute to the community, actualize their values, and gain satisfaction from promoting the mission of the organization. Is this public spiritedness an after-the-fact rationalizing of their choice to work in nonprofits? We think not. An examination of their volunteering habits suggest that the executive directors are indeed more public spirited than the average Canadian; their volunteering participation rates are higher as is their intensity of volunteering.

Our findings on what motivates executive directors to work in their nonprofit jobs despite the large negative wage differentials give credence to the theories of labour donation and compensating wage differentials used to explain lower wages in the nonprofit sector. In addition, our findings support the explanation that there is a self-selection of individuals into nonprofit leadership positions as these individuals receive many non-monetary rewards from their work. Thus, although nonprofits offer lower wages to executive directors compared to their counterparts in the for-profit sector, they are able to attract competent individuals who are likely to be motivated by the mission and who are generally more public spirited.

If the old adage ‘you get what you pay for’ holds, then it would imply that nonprofits were not attracting the best and the brightest as this necessarily involves compensating them. However, compensation, as we found, need not be in monetary terms; many individuals deliberately choose to work in this sector because of their values and beliefs and the sense of satisfaction they receive working for the public benefit in addition to the job characteristics particular to this sector. To recruit and retain the competent and dedicated individuals, low

Table 3: Responses to Open-Ended Questions on the Challenges of Working for a

Nonprofit Organization

• Financial insecurity is an enormous factor that is wearing down my interest in the sector.

• Challenge of earning revenues as grants decrease. Volunteer and staff exhaustion.

• Maintaining the core funding structure needed to operate!!!!! Mission drift because we are always seeking funding to operate which takes us down many different paths.

• Recruiting new highly skilled people because the salaries are poor. Balancing fund-raising time with providing services.

• Balancing expectations and capacity.

• Being directed by a volunteer board has been for the most part fine, but there have been times of being conscious that there were expectations that everything would be run with bigbusiness slickness, but with only the slim resources of a tiny organization.

• Constant challenge of ever-changing board members who are rarely qualified to serve on a board.

• Finding committed and qualified staff and volunteer board members. Managing staff and board in a quickly changing environment. Also, convincing board members of the importance of paying adequate salaries and benefits to attract competent staff.

• Below-average wages. Lack of structure and continuity due to constant changes in Board members- Working with a large number of volunteers and keeping them all happy.

• Low salary, long working hours because of lack of personnel, risks of burn out, non recognition of work value by the private sector, lots of «make work» or red tape imposed by government agencies.

• Working with directors and volunteers, negotiating different personalities and viewpoints.

• Motivating volunteers, not having enough money to do the things we want to do.

• I deal with volunteers and there is always the reality that at any moment they can stop their commitment to the organization. Also there is the continuing turn over of volunteers.

monetary wages will still be competitive if balanced with the positive aspects of the job and, by addressing some of the challenges respondents mentioned, such as educating volunteer boards to deal with paid staff. Opportunities for self-development, flexible work times, promoting a balanced lifestyle with their families, job stability or tenure, the ability to act on personal values and beliefs in creative ways to promote the nonprofits mission would increase satisfaction with the job and significantly compensate for the perceived negative wage differentials. The for-profit sector could not easily compete with these non-monetary compensating wage differentials, giving nonprofit organizations an edge in competent for talent and dedicated managerial staff.

In the final analysis, executive directors’ perceptions of their own wages are important. It is in this context that they are making choices of where to work. This, in turn, determines the managerial labor supply to the sector. To recruit executive directors who are competent and committed to guide nonprofit organizations to maximize public benefit, it is necessary that nonprofits enhance and advertise the many non-monetary positive benefits of working in this sector. Emphasizing the high moral ground of nonprofit jobs will maintain their competitive edge for managers in the market and downplay the perceived wage differentials.

REFERENCES

Almanac (2005, October 11). $2.5 million: Bendheim loan forgiveness fund for public service. University of Pennsylvania Almanac, 52(7). Retrieved February 4, 2007, from <http://www.upenn.edu/almanac/volumes/v52/n07/pdf_ n07/101105.pdf>

Ball, C. (1992). Remuneration policies and employment practices: Some dilemmas in the voluntary sector. In J. Batsleer, C. Cornforth, & R. Paton (Eds.), Issues in voluntary and nonprofit management: A reader (pp. 69–82). Wokingham, UK: Addison-Wesley.

Bell, J., Moyers, R., & Wolfred, T. (2006). Daring to lead 2006: A national study of nonprofit executive leadership. CompassPoint and the Meyer Foundation. Retrieved February 4, 2007, from <http://www.compasspoint.org/ assets/194_daringtolead06final.pdf>

Benz, M. (2005). Not for the profit, but for the satisfaction? Evidence on worker well-being in non-profit firms. Kyklos 58(2), 155–176.

Bond, C., Raehl, A., & Pitterle, M. (1999). Staffing and the cost of clinical and hospital pharmacy services in United States hospitals. Pharmacotherapy,

19(6), 767–781.

Borjas, G., Frech III, E., & Ginsburg, P. (1983). Property rights and wages: The case of nursing homes. The Journal of Human Resources, 18(2), 231–246.

Eckel, C., & Steinberg, R. (1994). Tax policy and the objectives of nonprofit organizations in a mixed-sector duopoly. Working paper 95–16. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University.

Emanuele, R. (1997). Total cost differential in the nonprofit sector: Some new evidence from Michigan. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 26(1), 56–64.

Emanuele, R., & Higgins, S. (2000). Corporate culture in the nonprofit sector: A comparison of fringe benefits with the for-profit sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 24(1) 87–93.

Frank, R. (1996). What price the high moral ground? Southern Economic Journal, 63(1), 1–17.

Goddeeris, J. (1988). Compensating differentials and self selection: An application to lawyers. Journal of Political Economy, 96(2), 411–428.

Handy, F., & Katz, E. (1998). The wage differential between nonprofit institutions and corporations: Getting more by paying less? Journal of Comparative Economics, 26(2), 246–261.

Hansmann, H. (1980). Economic theories of nonprofit institutions. In W. Powell (Ed.) The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (pp.27–42). New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press.

Holtmann, A., & Idson, T. (1993). Wage determination of registered nurses in proprietary and nonprofit nursing homes. The Journal of Human Resources,

28(1), 55–79.

Jeavons, T. (1994). When the bottom line is faithfulness. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Univ. Press.

Johnston, D., & Rudney, G. (1987). Characteristics of workers in nonprofit organizations. Monthly Labor Review, 110(7), 28–33.

Jones, J. (2003, February 1). 2003 Salary survey: Women gaining on men, as nonprofit salaries steadily increase. The Nonprofit Times. Retrieved February

4, 2007, from <http://www.nptimes.com/Feb03/sr1.html>

Klineman, J. (2004, November 25). Human resources from scratch. The Chronicle of Philanthropy. Retrieved February 4, 2007, from, <http://www. philanthropy.com/free/articles/v17/i04/04002501.htm>

Lanfranchi J., & Mathieu N., (2005). Wages and effort in the French for-profit and nonprofit sectors: Labor donation theory revisited. Working paper, ERMES, Université Panthéon-Assas, Paris II, France.

Leete, L. (2000). Wage equity and employee motivation in nonprofit and for profit organizations. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 43(4), 423–446.

Lewin, T. (2001, June 3). Women profit less than men in the nonprofit world, too. New York Times.

Light, P. (2003). Health of the human services workforce. Center for Public Service, The Brookings Institution. Retrieved February 4, 2007, from <http:// www.openminds.com/indres/HumanServicesBrookings.pdf>

Lipman, H. (2006, October 12). Pay gap narrows for male and female nonprofit executives, study finds. The Chronicle of Philanthropy. Retrieved February 4, 2007, from, <http://www.philanthropy.com/free/articles/v19/i01/01002801. htm>

Mason, D. (1996). Managing and leading the expressive dimension. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McKeown, L., McIver, D., Moreton, J., & Rotondo, A., (2004). Giving and volunteering: The role of religion. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

McMullen, K., & Schellenberg, G. (2002). Mapping the non-profit sector. Research Series on Human Resources in the Non-Profit Sector, 1. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Network.

Mirvis, P., & Hackett, E., (1983). Work and work force characteristics in the nonprofit sector. Monthly Labor Review, April 1983.

Naci Mocan, H., & Tekin, E. (2003). Nonprofit sector and part-time work: An analysis of employer-employee matched data on child care workers. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(1), 38–50.

Naci Mocan, H., & Viola, M., (1997). The determinants of child care workers’ wages and compensation: Sectoral differences, human capital, race, insiders and outsiders. Working Papers 6328, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Preston, A. (1988). The effects of property rights on labor costs of nonprofit firms: Application to the day care industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 36(3), 337–350.

Preston, A. (1989). The nonprofit worker in a for-profit world. Journal of Labor

Economics, 7(43), 438–463.

Roomkin, M., & Weisbrod, B. (1999). Managerial compensation and incentives in for-profit and nonprofit hospitals. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 15, 750–781.

Ruhm, J., & Borkoski, C. (2003). Compensation in the nonprofit sector. Journal of Human Resources, 38(4), 992–1102.

Shackett, J., & Trapani, J. (1987). Earnings differentials and market structure.

The Journal of Human Resources, 22(4), 518–531.

Shahpoori, K., & Smith, J. (2005). Wages in profit and nonprofit hospitals and universities. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved February 4, 2007, from <http://www.bls.gov/opub/cwc/cm20050624ar01p1. htm>

Steinberg, R. (1990). Profits and incentive compensation in nonprofit firms.

Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 1(2), 137–152.

Weisbrod, B. (1983). Nonprofit and proprietary sector behavior: Wage differentials among lawyers. Journal of Labor Economics, 1(3), 246–263.

Weisbrod, B. (1988). The nonprofit economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ.

Press.

Young, D. (1983). If not for profit, for what? Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

NOTES

1. See, for example, <http://www.employmentspot.com/features/nonprofit.htm>

2. The most notable scandal reported in the media was that of William Aramony. In 1992, he resigned as president of the United Way of America (UWA) after exposure and criticism of his lavish life style and $463,000 annual salary and benefits. His replacement was paid less than half his salary; however, the UWA faced donor and public distrust for many years.

3. See Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 241 / Friday, December 16, 2005 / Proposed Rules pp74721

4. Goddeeris (1988) raises doubts about the results obtained by Weisbrod (1983) regarding the observed wage differentials. He reworks the data to show that a selection bias may have resulted in the size of the differentials as noted by Weisbrod.

FEMIDA HANDY

University of Pennsylvania and York University

LAURIE MOOK

OISE, University of Toronto

JORGE GINIENIEWICZ

OISE, University of Toronto

JACK QUARTER

OISE, University of Toronto

This research was supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) INE Research Grant # 501-2002-203. The authors are grateful to all Executive Directors of Canadian nonprofits who participated in this study. We appreciate the insightful comments on an earlier draft by Itay Greenspan.

Femida Handy is an associate professor at the School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania and at the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University.

Laurie Mook is a PhD student at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education and the Director of the Social Economy Centre at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Jorge Ginieniewicz is a PhD student at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Jack Quarter is a professor of Adult Education and Counselling Psychology at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE/UT).