Introduction

In September 1999, the Ontario government instituted a new set of curriculum requirements for the Ontario Secondary School diploma, including a controversial 40-hour mandatory community service requirement. The benefits and drawbacks of school-based community service programs have been widely discussed in both educational and voluntary sector literature. While our research into previously existing community service programs in Toronto high schools shows that limited benefits result from unstructured programs such as the Ontario example, this article revisits those factors that make for successful community service programs five years after the Ontario program’s implementation. We demonstrate that the effectiveness of in-school community service programs depends less on whether or not they are mandatory, and more on the program structure. Key structural characteristics of school-based programs that benefit students and the community as a whole include student opportunity for meaningful work, input, and reflection, as well as committed on-site adult supervision.

Brief Overview of Voluntary Service in Canada

Historically, in North America and in Britain, volunteer behaviour—the active participation in helping the poor and the needy, as opposed to merely the giving of alms—was initiated by religious institutions. This formed the foundation of many social welfare services (de Schweinitz, 1943; Feingold, 1987). But by the beginning of the 20th century, helping the poor became more secularized and professionalized as social workers gradually replaced religious volunteers, and congregational voluntary action declined (Cnaan, Kasternakis, & Wimeberg, 1993). The state formed a partnership with nonprofit organizations to provide essential social services, and volunteers were seen as adjuncts to professionals. In Canada, during the two decades following WWII, the federal and provincial governments, through the provision of generous operating grants, encouraged the formation of nonprofit social service organizations providing professional care. They were part of an elaborate social welfare system that extended specialized services that the government was uninterested in or unable to provide. Not only did these organizations receive generous funding from government sources but, more importantly, they also gained legitimacy to represent and serve their various constituencies (Tucker, Singh, & Meinhard, 1990).

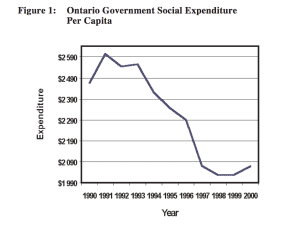

Whereas during the post-war decades there was close cooperation between governments and the voluntary sector, the last two decades have seen a gradual erosion of the social welfare state (Evans & Shields, 1998). In Ontario, with the election of Mike Harris in 1995, the drop in social expenditures was precipitous, as demonstrated in Figure 1.5 These drastic cuts were carried out within the framework of the Common Sense Revolution, a political platform that identified reliance on personal volunteering as part of a strategic reallocation of services.

Figure 1: Ontario Government Social Expenditure Per Capita

The contribution of volunteers continues to be encouraged and valued, both by current governments and also by nonprofit groups seeking program and fundraising support in a time of rapid change. For example, provincial and federal governments have reinforced the shift towards increased volunteerism by supporting initiatives such as the 1998 Ontario Voluntary Forum and the 2001

International Year of Volunteers. In some sectors, however, there is strong opposition to this emerging social philosophy. High volunteer turnover rates, high costs of training, threat of job losses for paid employees, and the risks involved in replacing university-trained professionals by volunteers, are all potent arguments that have been put forward against the replacement of paid staff by volunteers (e.g., Lefebvre, 1996). Nevertheless, the reality is that government funding for social and cultural services continues to decrease substantially (Hall & Banting, 2000). Given this situation, organizations may benefit from a larger and better-educated pool of volunteers. Indeed, in a recent study of the value-added contribution of hospital volunteers, Handy and Srinivasan (2003) calculated that for every dollar spent on the volunteer program, the hospital derived an average of $6.84 in value.

The scope of volunteering in Canada is impressive. According to the National Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating conducted in 2000, 27 % of Canadians volunteered through a charitable or nonprofit organization, for a total of 1.05 billion hours during the year (Hall, McKeown, & Roberts, 2001). This is equivalent to 549,000 full-time jobs. Conservatively calculated against the 2000 average hourly wage in Canada of $15.52, the dollar value of this donated labour was more than $15.5 billion.6 However, the volunteering trend is sloping downward, with a 6% decrease in the number of volunteers between 1997 and 2000. Of these Canadian volunteers, youth constitute a significant force; young people between the ages of 15 and 24 accounted for 154 million volunteer hours or 15% of all volunteer hours. Additionally, youth between the ages of 15 and 19 had the highest volunteer rate of all age groups—27%. Almost 20% of these youth volunteers were required to volunteer by their schools, places of employment, or the government (Hall et al., 2001).

Community involvement and charitable giving have traditionally been facilitated through religious institutions, as service to others and the obligation to helping the poor is central to all religious teaching (Feingold, 1987). Indeed, surveys of the determinants of youth voluntary action have consistently pointed to the importance of religious affiliation, parental example, and involvement in school groups as three of the strongest factors in predicting volunteer participation (Hodgkinson & Weitzman, 1997; Hall et al., 2001). Put simply, youth whose parents are volunteers and who are affiliated with organized religion and organized school activities are more likely to volunteer.

However, in an increasingly secularized society, it is unrealistic to rely on religious institutions to socialize the general citizenry to community involvement and social action. Wuthnow (1991) found that religious institutions’ primary goals are to encourage members first and foremost to volunteer for the benefit of the congregation; this does not necessarily translate into increased volunteer activity for the general good. This indicates that in order to instill community involvement in young people, other forms of socialization are needed. The three pillars of North American society—home, school, and religious institution—all predispose teenagers to become volunteers (Sundeen & Raskoff, 1994).

School-Based Community Service

There is increasing evidence, mostly from the United States, that schools can play a significant role in supporting and encouraging civic responsibility. In the United States, the concept of school-based “service learning” dates back to the writings of John Dewey at the turn of the last century; he pointed to the “importance of social and not just intellectual development; and the value of actions directed towards the welfare of others” (Kraft, 1986, p. 133). While mandated community service has also been used in the justice system to encourage rehabilitation in young offenders, many proponents of mandatory school-based community service have promoted an approach that is more integrated than simply sending youth into the community. “Service learning” is an educational approach that links community service directly to the school curriculum. Commended as an antidote against the decline in communal and civic participation witnessed over the past half century (Barber, 1992; Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1985; Putnam, 2000), it has enjoyed renewed interest in the past two decades. Service learning is described as an interdisciplinary instructional strategy in which students learn and develop through active participation in thoughtfully organized service experiences that meet actual community needs and that are coordinated in collaboration with school and community; that is integrated into students’ academic curriculum or provides structured time for students to think, talk or write about what that student did and saw during the actual service activity; that provides students chances to use newly acquired skills and knowledge in real-life situations in their own communities; and that enhances teaching in school by extending student learning into the community and helps foster a sense of caring for others (Kraft, 1996).

The concept of service learning is well established in the United States. Since 1993, a major federally funded program, Learn and Serve America, has existed in order to involve “school aged youth in program and classroom activities that link meaningful service in the community with a structured learning experience” (Melchior, 1997, p.1). Service learning has helped to bridge the ideological divide between the individual pursuit of happiness and the good of the community that many scholars have remarked upon in the United States (Barber, 1992; Bellah et al., 1985; Putnam, 2000). However, this tension is not characteristic of Canada. As opposed to every individual’s right to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness,” as stated in the Declaration of Independence, the preamble of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1867, talks of “Peace, Order and Good Government.” For many historical reasons, the common good has generally taken precedence over individual rights. The Canadian government has always been more involved in the management of both the economy and the welfare of its citizens. Thus the partnership between government and the nonprofit or voluntary sector has a different form in Canada than in the U.S. (Shields & Evans, 1998, p.17). Voluntary social service organizations have traditionally been viewed as part of the public sector because of the symbiotic nature of the relationship; it is the obligation of governments at all levels to support social services. As a result, there has been no national initiative in Canada such as the Learn and Serve America program, as Canada’s social service delivery system has traditionally mobilized significant professional and voluntary labour. However, the deep-seated belief in a strong state role in Canadian society has been undermined in the name of “fiscal restraint and the new competitive global order” (Shields & Evans, 1998, p 17). This has significantly changed the environment in which the voluntary sector exists. Concurrent to this changing philosophy, governments in some Canadian provinces and territories have begun considering and implementing mandatory community service programs for secondary schools.7

The Ontario Example

In Ontario high schools, community service programs have long existed as part of co-op placements, extracurricular activities, and specific courses such as Civics and World Issues. Then, in 1999, as part of a complete overhaul of Ontario’s secondary school curriculum, the government mandated 40 hours of community service as part of graduation requirements. This highlights the government’s interest in playing a more active role in socializing youth to the importance of community involvement and charitable giving. The stated intention of the service component is to “encourage students to develop awareness and understanding of civic responsibility and of the role they can play in supporting and strengthening their communities” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 1999). The policy provides no direction on how the service component should be implemented or linked to curriculum; this is contrary to ample evidence indicating that simply appending community service hours to graduation requirements without linking it to learning objectives is not optimal.

Given that the voluntary sector lacks the visibility and public awareness commonly accorded the private and government sectors (Salamon & Anheier, 1996), voluntary agencies might have welcomed this widely publicized policy in order to recruit youth volunteers. In fact, in the 2000 NSGVP survey, the most common reason given by youth for not volunteering was “not knowing” where to volunteer (Hall et al., 2001). The mandate effectively eliminated this barrier, as schools and parents (and by extension, voluntary agencies) were expected to inform students of potential community service activities. But any potential enthusiasm on the part of voluntary agencies was dampened by a lack of consultation. This garnered considerable criticism as many questioned if sufficient sectoral capacity existed to introduce large numbers of youth into community service placements, particularly in an age of budget cuts to volunteer recruitment and management staff. The new mandate also prompted an ongoing debate about the ideological underpinnings of “mandatory volunteerism,” as many have argued that volunteers should not be relied upon as a substitute for government action on social problems (O’Connell & Valentine, 1998; Bloom & Kilgore, 2003; Halton Social Planning Council, 2001; Graff, 2003). This paradoxical catchphrase, exploited by media and policy opponents, has unfortunately become the central point of debate surrounding the mandate. While an important topic of discussion in the context of changing government attitudes towards social policy more generally, this overstated focus on the program’s mandatory nature has detracted from debate on the learning structure of the program, which, judging from studies on the effects of community service programs, is much more directly linked to successfully inculcating social responsibility and civic-mindedness in students.

Evaluating the Effects of School-Based Community Service Programs

Although theoretical models suggest “that community service may promote competence and self-esteem, reduce levels of problem behaviours, provide greater knowledge of community problems and advance cognitive and moral development in adolescents” (Moore & Allen, 1996, p. 224), empirical evaluations of various community service programs across North America have yielded mixed results. This is not surprising as community service itself is so multi-faceted as to make it difficult to compare across programs. Tasks ranging from babysitting neighborhood children, to collecting recyclable materials within the school, to shelving parts at an automotive business, to orienting parents at school events were all mentioned as eligible service activities in our recent interviews with educators.

Kraft (1996), in a review of evaluative studies of service learning programs, concludes that there is “a lack of solid evidence on the effects of these programs” because it is “difficult to isolate the effects of service on specific academic achievements” (p. 143). Based on his review, he summarizes the impact of community service programs in five separate areas:

1. Social growth: The findings are mixed although there is some evidence that indicates that students acquire a greater sense of social responsibility and become more service oriented, less prejudiced, and more democratic.

2. Psychological development: There is evidence that service learning programs enhance positive self-image and increase self-confidence and self-esteem.

3. Moral judgment: The results are very mixed, but there is some evidence of impact on moral judgment.

4. Academic learning: Again results are mixed. In general tests of knowledge, there is usually no difference between service learners and the control groups, but on measures of reading and math achievement scores of tutors, there is improvement.

5. Impact on community served: Results in this area are less equivocal as evidence indicates that young volunteers have a positive impact on the community.

A number of studies are more concerned with whether there are differences between mandatory or voluntary community service in determining student and community benefits. Warburton and Smith (2003) found that Australian young people are very conscious of the lack of choice in mandatory community service programs. Teenagers feel resentment and frustration at the lack of personal development offered in limited programs and also experience exploitation as unpaid labourers. As a result, the Australian programs fail to develop positive community attitudes and active social behaviours. Miller (1994), in a gender-based analysis of mandatory school-based community service, finds that male students react more negatively to compulsory programs than female students; male students were more likely to focus on the perceived injustice of the proposed method whereas female students were more likely to focus on the motive of encouragement underlying the message. Stukas and his colleagues (1999), in two studies of university students in Minnesota, propose that only those individuals who would otherwise not be volunteering or who feel that it would take external control to get them to volunteer may find their future intentions to volunteer undermined by a mandatory requirement. Still others consider mandatory service programs to be a form of forced student labour that detracts from a primary goal of academic achievement (Sanchez, 1998; Hurd, 2004).

Other research downplays the controversy surrounding required and voluntary service, citing an implicit privileging of the latter over the former; other-initiated service is considered less “natural” than a spontaneous, individualized, and voluntary desire to participate. If the likelihood of youth participation in community service is predicated on “action that follows from available resources” (McLelland & Youniss, 2003, p. 56), mandatory school-based programs offer all youth an equal opportunity to become involved in their community. The distinction becomes less important if the end goals of community service are increased awareness and understanding of civic responsibility. In this light, mandatory school-based programs help to eliminate the greatest barrier to youth involvement: lack of knowledge of available opportunities.

Far more important is the extent to which schools structure the service experience. McLelland and Youniss (2003) suggest that noncomparability across empirical studies of community service programs may be more directly linked to variation in the factors that define the structure of the program rather than the type of service. They suggest that the more highly structured the programs, the greater the positive impact on the student. Two extremes of variation appear to characterize the spectrum of programming across high schools with some schools “organizing service tightly within the academic curriculum and others requiring service, but leaving its integration mainly up to the individual student” (McLelland & Youniss, 2003, p. 49). Because the Ontario mandate makes no mention of structure, many schools, for lack of capacity and resources, have defaulted to implementing the program according to the latter model.

Our Findings: Before Mandatory Service Implementation

In a 1997 survey of 162 public, Catholic, and private secondary schools in Toronto, we found that almost half had mandatory or optional community service programs of some sort. Students volunteered for an average of 34 hours per semester in schools where the program was optional, but only 12 hours per semester in schools where the program was mandatory. This seems to indicate that voluntary programs, as opposed to mandated ones, are more enthusiastically embraced by students (Meinhard & Foster, 1998).

In the second stage of the research we compared student volunteers to nonvolunteers on measures including educational competence, personal and social responsibility, acceptance of diversity, communication skills, work orientation, engagement in service, leadership, formal helping behaviour, and selfesteem8 (Meinhard & Foster, 1999; Foster & Meinhard, 2000). The volunteer students in our sample were divided almost equally between those who directly helped other people (45%) and those whose contribution was indirect (40%). The former, for example, volunteered in nursing homes, shelters, or youth groups where they tutored and mentored. The latter were involved in charitable causes that required raising money or collecting food or clothing, etc. to be channeled to where it was most needed. The remaining 15% helped in the community by recycling cans, cleaning a park, or getting signatures on a petition. Although direct volunteering is considered the most “transformative” as students have the opportunity to see their efforts appreciated by those who most benefit, there were no significant differences on any of the measures among the three types of volunteers.

While almost half of the student volunteers reported that their volunteering was very meaningful, approximately one quarter to one third of the students were unhappy in their placements and/or did not find the work meaningful. We attributed this dissatisfaction to a lack of direct adult involvement and inadequate follow-up at school. The unsatisfied students reported few opportunities to share their experiences with teachers, fellow students, or adult supervisors at their placements; they were more likely to be left to their own devices.

When volunteers were compared with non-volunteers on the various scales, we found that they scored significantly higher on self-esteem and social responsibility items such as: a) the importance of doing one’s best; b) deserving to be loved and respected; c) satisfaction with themselves; d) realizing that they can make mistakes without losing love and respect; and e) realizing they don’t need the approval of others to be happy and satisfied.

Most importantly, participation in a high school community service program does seem to predispose young people to future volunteering. Approximately two thirds (65%) of the participants indicated that they would continue to volunteer later in life. For many of them, these intentions have already been translated into behaviours; 54% report having done additional volunteering over and above their community placement activities.

The conclusions gained from the 1998 study are:

1. Meaningful work is essential for students to benefit from the program.

They want real responsibility, challenging tasks, and a variety of activities.

2. Projects should be chosen or designed so that students can have significant input into what they are doing. This serves to increase involvement and commitment, and ultimately satisfaction and the positive impacts of participation on social development.

3. Student experiences are enhanced when there are opportunities for feedback and reflection. This includes in-class processes in addition to discussions with family and friends about their experiences.

4. Adult support enhances improvement in social development and commitment to future volunteering; therefore, it is essential to ensure that there be committed and adequate on-site adult supervision.

Assessing the Current Ontario Model

Currently there is no official evaluation of the community service required to obtain Ontario’s secondary school diploma. From interviews with selected teachers and principals of Toronto secondary schools, we have learned that, to the best of their knowledge, there have been no unofficial evaluations either. To date, the only attempt to gauge the impact of the program on the students was a study conducted by Padanyi, Meinhard, and Foster (2003).

First Cohort of Graduating Students With Community Service

Requirements

Taking advantage of the “double cohort”9 phenomenon, Padanyi and her colleagues were able to compare first-year students who completed the fouryear compulsory community service program to those who graduated without this requirement. Their sample consisted of 265 incoming students at University of Guelph. Thirty percent were part of the Ontario mandatory program. Of these students, 39% did extra volunteering outside of the program. Seventy percent of the students had no service requirement; however, 46% of those volunteered on their own initiative. Table 1 illustrates the distribution according to the two main categories and four sub-categories.

Table 1. Distribution of Sample of First-Year University Students

|

Mandatory Community Service Program (n=80, 30%) |

No Service Requirement (n=185, 70%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

Group D |

|

Exclusively n=49, 61% (18% of total) |

Extra Volunteering n=31, 39% (12% of total) |

No volunteering n=100, 54% (38% of total) |

Volunteering n=85, 46% (32% of total) |

There are some interesting similarities and contrasts between these groups. Students who did not volunteer or who volunteered only because of the high school requirement (Groups A and C) were less likely to come from families where parents volunteered and to attend religious services regularly. On the other hand, students who volunteered of their own initiative (Groups B and D) were more likely to come from families where the parents volunteered and to attend religious services. These findings are similar to those of the National Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating in Canada (2000) and the Independent Sector Survey in the U.S. (Hodgkinson & Weizman, 1997).

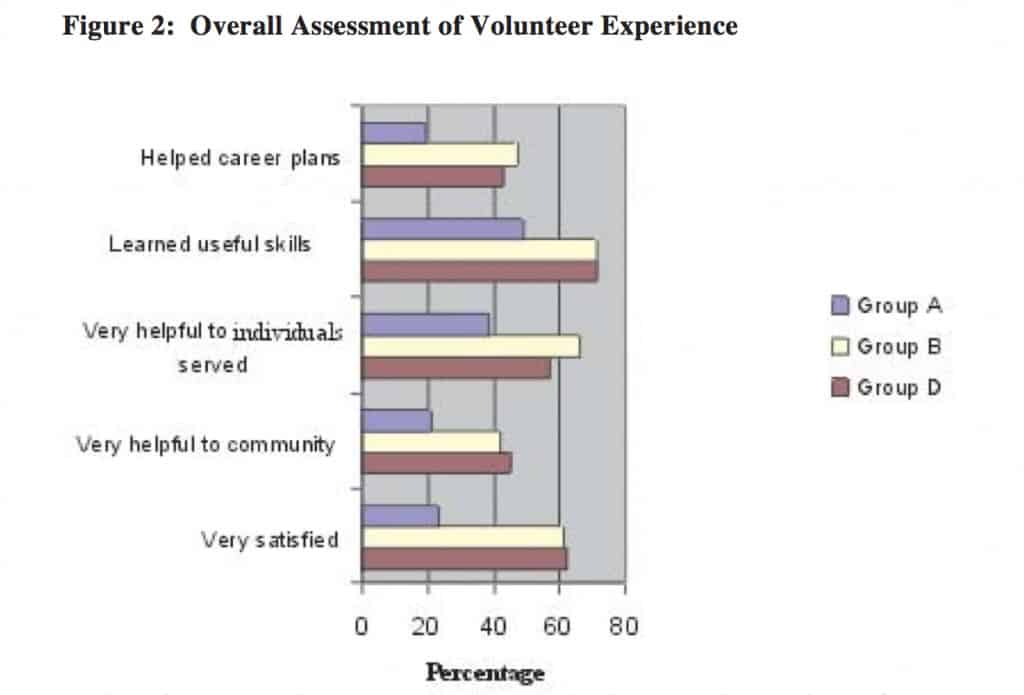

Comparing only the three groups of students who volunteered, Padanyi and her colleagues found that students volunteering exclusively in the mandatory program consistently rated items measuring their volunteering experience less positively than students who volunteered on their own or those who did the mandatory program and volunteered outside it as well. See Figure 2 for a full breakdown.

Figure 2: Overall Assessment of Volunteer Experience

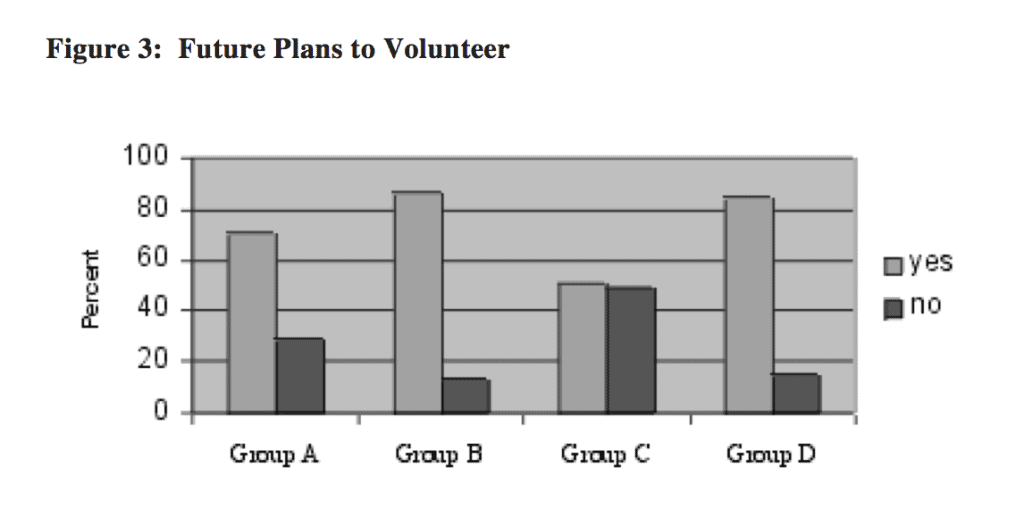

Students in the sample were asked about their plans to volunteer in the future. Only 13% and 15% of students who volunteered on their own (Groups B and D) said they did not intend to volunteer in the future. Twice as many students (29%) who volunteered only through the mandatory program (Group A) claimed they were unlikely to volunteer in the future. Among those who never volunteered, almost half indicated that they had no plans to volunteer in the future (Figure 3).

The difference in intended volunteering between the mandatory volunteer group and the non-volunteer group suggests that there is an exposure benefit

Figure 3: Future Plans to Volunteer

that results from the mandatory program, with students otherwise not volunteering declaring a future intention to do so. This notwithstanding, it is disconcerting to see such low levels of satisfaction among the mandatory service students. Relating this finding to those of the earlier Meinhard and Foster studies (Meinhard & Foster, 1999; Foster & Meinhard, 2000), those by Sundeen and Raskoff (Sundeen & Raskoff, 1994; Raskoff & Sundeen, 1998; Raskoff & Sundeen, 1999) and McLellan and Youniss (2003), we wonder what would have been the case had the Ontario program been more structured, including building partnerships with voluntary agencies, providing opportunities for students to share their experiences with others, and helping students understand the context for their volunteering. It seems plausible that the more positive the volunteering experiences of the students, the mandatory nature of the program notwithstanding, the greater the likelihood of continued volunteering in the future.

Because it appears that the Ontario program, as currently mandated, has not incorporated these lessons in its program design, it is unlikely to benefit students and communities in substantial and measurable ways.

Follow-Up Interviews

In 2004, we conducted informal follow-up interviews with educators at some of the schools that participated in our initial 1996 study. While the information gathered is primarily anecdotal and in no way as systematic as our initial survey, several themes emerged in these interviews that are consistent with the findings of previous researchers.

First, all educators agree that the compulsory community service component offered all students, regardless of background, gender, prior experience, race, or income status, an equal opportunity to learn through community service. The exposure benefit of a mandatory program should not be underestimated.

However, the drawback of this across-the-board equal access to learning benefits is that the program equally expects 40 hours of community service from all students. Many students are unable to participate in community service. Students who are expected to care for younger siblings or supplement family income through part-time work have very little time for community service. Students new to Canada, who face a language barrier, also have difficulty securing community service placements. As a result, some educators have created alternatives such as service projects within the school at lunch hours, assigning community service credit to childcare duties within the family, and offering lower hour standards for students new to Canada. Educators express concern that the program doesn’t fully appreciate the range of existing commitments among students.

Second, even after five years of the mandatory program, many educators question the value of a compulsory program. Many point out that the students who are visibly benefiting from the program are students who most likely would have been volunteering in the community regardless of the curriculum requirement. These students often report hours that well exceed the 40-hour mandate. These observations are confirmed by the University of Guelph study (Padanyi et al., 2003). Other educators we interviewed point out that the students who are most resistant to the requirement are still very unlikely to benefit, as the program does not ensure the quality of the placement, only that the required number of hours has been met. One teacher worries about mandatory community service being viewed as punishment by students, akin to community service mandated for young people convicted of crime.

Next, educators are concerned that meaningful placements are not the norm. The wide range of placements that meet the criteria (since the only limiting characteristic of the Ontario mandate is that service must be non-paid) results in many service experiences characterized by functional tasks. Educators express concern that meaningful, “transformative” placements with direct personal contact with other community members are not the norm. This echoes research that finds that students, if left to their own devices, will most often choose work that “demands less physical, cognitive, or emotional investment compared with social service” (McLellan & Youniss, 2003, p. 56). Some educators voice concern that students are completing their community hours at for-profit firms, which they felt was contrary to the spirit of the requirement. Notably, the mandate does count any service that takes place in “businesses, not-for-profit organizations, public sector institutions (including hospitals), and informal settings” (OME, 1999, section 3.1.3).

Educators agree that the program would greatly improve if there was additional structure—in particular, if more work were done to ensure meaningful placements are found that are “transformative” and encourage personal contact with other people in the community. While there is some assistance in locating placement opportunities (bulletin boards, PA announcements, community information in the guidance office), there is little or no follow-up on the placement experience due to a lack of staff time. While the type of school system affects the type and extent of community service program (in our initial study we found that private and Catholic schools were more likely to have programs), every educator consulted in all types of schools noted that their program does not provide enough staff time to create meaningful placements for students. Students submit their logs of community service hours with contact information for their supervisors; however, not one educator interviewed had ever contacted a supervisor to review the service experience. While all schools note enthusiasm for the program, the resources to implement a meaningful and successful structured program have never been provided. Educators voice frustration about the situation. Unless placements are well planned (which seems unlikely given the downloading of other administrative tasks on school staff and teachers in the past five years), the experience will not result in the positive social development and life-long commitment to community service that is desired.

At the same time, the lack of staff time for the service program has led some senior students to take on increased responsibility. For example, some schools report that information about volunteer opportunities is collected by senior students and shared, in a variety of ways, with younger students. While educators are positive about the increased leadership of these students, one also felt that these tasks should not necessarily fall to volunteer student labour.

Last, many educators are reluctant to comment generally about the effects of the mandatory program, even though it has been in existence for five years, sufficient time for some reflection on its suitability. Why? Tellingly, when asked if she noticed any benefits of the program, one educator said:

No. There has to be light reflecting off the program to see results—and I can’t see anything, because all I see is the reports on the number of hours. Previously, in my class where students did community service, the students did reports, I did one—on-one interviews with them, they did large presentations… now [with the mandatory program] there is nothing to reflect light. No one is asking questions about the effectiveness of the program. (Interview #3, 2004)

Not one educator noted any review or evaluation of the community service mandate, either at a school or board level. Calls to the Ministry of Education confirm that no official provincial review of the initiative has yet been undertaken.

Role of the Voluntary Sector

Voluntary organizations have a key role to play in the successful outcome of community service experiences. Sundeen and Raskoff (1994; 1998) point to the importance of forging partnerships among the schools, the students, and voluntary agencies in order to achieve the greatest benefit for both student and the community. Agencies determine whether the student does meaningful work, the quality of the adult supervision, and the level of participants’ input into the project. It is therefore somewhat disconcerting that the Ontario program involves no formal partnerships or dialogue with the voluntary sector organizations that are in part responsible for providing opportunities and supervising students. Educators note the increased presence of community organizations in their schools looking for student volunteers as a result of the mandate, but one questions if an increased volunteer labour pool as a result of the program is truly benefiting the voluntary sector. These concerns are echoed by those in the volunteer sector (Graff, 2003). While superficially the voluntary sector and the educational policy sector recognize community service as beneficial to students, schools, and the community, the lack of dialogue on what constitutes effective programming results in a critical lack of understanding of the issues involved.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The ongoing erosion of both human and financial resources flowing to nonprofit organizations has led the voluntary sector and its government sponsors to reassess the role of volunteers in the provision of community and social services. In Ontario, an important plank in the government’s retrenchment strategy was the encouragement of renewed individual volunteering to replace some of the losses in services caused by the cuts in government funding. With this in mind, the government mandated 40 hours of community service as a requirement for graduation from high school.

The program was part of revamping the general curriculum. Guidelines were issued without the benefit of consulting key players in the voluntary sector. Although welcoming such a program, many in the sector, particularly directors of volunteer centres, were concerned about the lack of lead time to set up the kinds of opportunities that would give students challenging and meaningful work. They were also worried about the sector’s ability to process the influx of hundreds of thousands of students over the first four years of the program.

Government guidelines to schools about the program were brief and straightforward. Forty hours of community service were now added to the requirements for graduation. These 40 hours could be achieved in any way, including volunteering at for-profit organizations, and they could be performed at any time during the four years, either concentrated in one year or spread over all four. Other details were left to the discretion of individual schools. While there was flexibility, because the community service program was part of a massive general curriculum change, little time or energy was left for innovative and constructive implementation of this program. Thus it was left to students to find their own placements, generally without meaningful help from school staff. Further, the University of Guelph study found a large proportion of students scrambled to fulfill their requirements in the last semester of high school. The study also points to the generally low levels of satisfaction and perceived benefit among those students whose sole volunteering experience was through the mandatory community service program.

Since beneficial outcomes flow most directly from linking community service to a structured school activity and from engaging in partnerships with nonprofit organizations, simply adding community service to graduation requirements will likely not produce increased civic mindedness and volunteerism among students whose sole experience with volunteering is through the mandatory program. Clearly, an opportunity was missed with the first cohort of students. There is, of course, still time to strengthen the program in the future. The first step should be to conduct an official program evaluation under the auspices of the Ontario Ministry of Education. This would identify what works well in the program and what does not. A survey of similar programs in other jurisdictions and consultation with students, teachers, and volunteer coordinators may lead to concrete ideas for improvement as well as foster greater commitment from teachers and voluntary agencies working directly with students. Finally, a structured program requires resources; there must be a willingness on the part of the Ministry of Education and the school boards to budget accordingly.

There is general agreement that the thinking behind required community service in Ontario’s secondary schools is sound. However, without further opportunities for meaningful volunteer work, student reflection, and additional adult support, the program as currently implemented will not yield substantial results. With significant evaluation and support from the educational field, government policy makers, and nonprofit managers, the program can be effectively retooled to benefit all.

REFERENCES

Barber, B. (1992). An aristocracy of everyone. New York: Ballantine.

Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. (1985). Habits of the heart. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bloom, Leslie R., & Kilgore, Deborah. (2003). The volunteer citizen after welfare reform in the United States: An ethnographic study of volunteerism in action. Voluntas, 14(4), 431–454

Cnaan, R., Kasternakis, A., & Wineberg, R.J. (1993). Religious people, religious congregations, and volunteerism in human services: Is there a link? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 22(1), 33–51.

de Schweinitz, K. (1943). England’s road to social security. New York: Barnes. Evans, B. M., & Shields, J. (1998). Reinventing the third sector: Alternative service

delivery, partnerships and the new public administration of the Canadian postwelfare state. Toronto: Centre for Voluntary Sector Studies, Faculty of Business, Ryerson University, Working Paper Series, Number 9, May 1998 <www.ryerson. ca/cvss/work.html>.

Feingold, M. (1987). Philanthropy, pomp and patronage: Historical reflections upon the endowment of culture. Daedalus, 116(1), 155–178.

Foster, M.K, & Meinhard, A.G. (2000). Structuring student volunteering programs to the benefit of students and the community. Presented at the Fourth International Conference of the International Society for Third Sector Research, Dublin, Ireland.

Government of Ontario. (1990–2000). Summary of expenditure by standard accounts classification and ministry. In Ontario Public Accounts 1989–2000. Toronto: Queen’s Printer.

Graff, L.L. (2003). Genetic engineering of the volunteer movement. In S. J. Ellis (Ed.), The rants and raves anthology: What’s on the minds of leading authors in the volunteer world (pp. 6–11). Philadelphia, PA: Energize, Inc.

Hall, M.. & Banting, K.G. (2000). The nonprofit sector in Canada: An introduction.

The nonprofit sector in Canada. Montreal and Kingston: School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University.

Hall, M., McKeown, L., & Roberts, K. (2001). Caring Canadians, involved Canadians: Highlights from the 2000 National Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating. Ottawa: Statistics Canada <http://www.givingandvolunteering.ca/ pdf/ n-2000-hr-ca.pdf>.

Halton Social Planning Council & Volunteer Centre (2001). The role of the voluntary sector—providing services? engaging citizens? Community Dispatch. 6 (1), 3–6. Burlington, Ontario: Halton Social Planning Council & Volunteer Centre <http:// www.cdhalton.ca/dispatch/cd0601.htm>.

Handy, F.. & Srinivasan, N. (2004). Valuing volunteers: an economic evaluation of the net benefits of hospital volunteers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(1), 28–54.

Hodgkinson, V.A., & Weitzman, M.S. (1997). Volunteering and giving among American teenagers 14 to 17 years of age: 1996 edition. Washington, D.C.: Independent Sector.

Hurd, M.J. (2004). “Giving back”: involuntary servitude for the young. Capitalism

Magazine. <http://capmag.com/article.asp?ID=3635>

Kraft, R. (1996). Service learning: An introduction to its theory, practice and effects.

Education and Urban Society, 28(2), 131–159.

Lefebvre, B. (1996). From minutes of the standing committee on general government, Government of Ontario. Timmins Ont.: June 16, 1996.

McLellan, J.A., & Youniss, J. (2003). Two systems of youth services: determinants of voluntary and required youth community service. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(1), 47–58.

Meinhard, A.G., & Foster, M.K. (1999). The impact of community service programs on students in Toronto’s secondary schools. Presented at the annual conference of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action, Washington, D.C.

Meinhard, A.G., & Foster, M.K. (1998). Survey of community service programs in Toronto’s secondary schools. Presented at the annual conference of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action, Seattle, WA.

Melchior, A. (1997). National evaluation of Learn and Serve America school and community-based programs. Centre for Human Resources, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA.

Miller, F. (1994). Gender differences in adolescents’ attitudes towards mandatory community service. Journal of Adolescence, 17, 381–393.

Moore, C.W., & Allen, J.P. (1996). The effects of volunteering on the young volunteer.

The Journal of Primary Prevention, 17(2), 231–258.

O’Connell, A., & Valentine, F. (1998). Speaking out project: Periodic report #3: Centralizing power, decentralized blame: What Ontarians say about education reform. Ottawa: Caledon Institute of Social Policy.

Ontario Ministry of Education. Ontario secondary school, grades 9–12: Program and diploma requirements. Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1999 <http://www.edu.gov. on.ca/eng/document/curricul/secondary/oss /oss.html>.

Padanyi, P., Meinhard, A., & Foster, M. (2003). A study of a required youth service program that lacks structure: Do students really benefit? Presented at the annual conference of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action, Denver, CO.

Putnam, R.D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Toronto: Simon & Schuster.

Raskoff, S., & Sundeen, R. (1999). Community service programs in high schools. Law and Contemporary Problems, 62, 4.

Raskoff, S., & Sundeen, R. (1998). Youth socialization and civic participation: The role of secondary schools in promoting community service in southern California. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 27(1), 66–87.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1996). The emerging nonprofit sector: An overview.

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Sanchez, M.S. (1998). Mandatory volunteerism: An interview with Paul Saunders.

Capitalism Magazine. <http://capmag.com/article.asp?ID=186>

Sundeen, R., & Raskoff, S. (1994). Volunteering among teenagers in the United States.

Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 23(4), 383–403.

Tucker, D.J., Singh, J.V., & Meinhard, A.G. (1990). Organizational form, population dynamics and institutional change: A study of birth patterns of voluntary organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 151–178.

Warburton, J., & Smith, J. (2003). Out of the generosity of your heart: Are we creating active citizens through compulsory volunteer programmes for young in Australia? Social Policy & Administration, 37(7), 772–786.

Wuthnow, R. (1991). Acts of compassion: Caring for others and helping ourselves.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

NOTES

1. This research was supported in part by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Institutional Grants Division. We wish to thank our research assistants, Grace Kim, Louise Moher, Tamara Hecht, Grace MacDonald, Chantal Hall, and Maame Twum-Barima for their dedication and perseverance. Special thanks to respondents who gave so generously of their time.

2. Dr. Agnes Meinhard is Associate Professor of Organizational Behaviour and Theory in the School of Business Management at Ryerson University. She is the founding director of the Centre for Voluntary Sector Studies at Ryerson and was instrumental in establishing Canada’s first undergraduate interdisciplinary curriculum in nonprofit and voluntary sector management at Ryerson University.

3. Dr. Mary K. Foster received her doctorate from Columbia University and is currently the Associate Director of the Centre for Voluntary Sector Studies and a Professor of Marketing in the School of Business Management at Ryerson University. She has recently developed a research program in management education.

4. Pike Wright received her Honours BA in International Development and Women’s Studies from Trent University. After working in the nonprofit field, she joined the Centre for Voluntary Sector Studies in October 2004. She provides key research and writing support for the Centre’s researchers. She is also a freelance journalist and writer.

5. Figure 1 was calculated using figures from the Government of Ontario’s Summary of Expenditure by Standard Accounts Classification and Ministry, located in the yearly Ontario Public Accounts from 1989–2000.

6. This figure was calculated using data published by Global Policy Network (<www.globalpolicynetwork.org>) and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (<www.policyalternatives.ca>), October 5, 2000. Accessed at <http://www.gpn.org/data/canada/canadaanalysis.pdf>, on July 20, 2005.

7. Provinces and territories that mandated community service as a high school graduation requirement include British Columbia and Northwest Territories, as of August 2003.

8. The research was carried out as a classical experimental design with the experimental volunteer group and the control group matched in every way. Self-esteem and growth measures were taken both before the volunteer program started and just after it was completed. We were granted permission to use the same instrument developed at Brandeis University that was used to evaluate the Learn and Serve America program.

9. Previous to 1999, the Ontario High School curriculum was a five-year program, grades 9–13. In 1999 the curriculum was changed so that it would be completed in four years. The compulsory community service program was part of this new curriculum. This meant that in 2003 incoming university students were made up of those who had started high school in 1998 and were not subject to mandatory service, and those who had started in 1999 and were the first graduates of the program. This is what is referred to as the “double-cohort” of incoming university students.

AGNES MEINHARD,2 MARY FOSTER,3 and PIKE WRIGHT4

Centre for Voluntary Sector Studies, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario