Accounting policies for nonprofit organizations have come under considerable scrutiny in recent years. An influential segment of the accounting profession is pushing for accounting policies that are virtually identical to those used in business. Many individuals and organizations in the voluntary sector, however, are actively opposing the suggested changes.1

The proposed changes in accounting policies concern not only the nonprofit organizations themselves, but also philanthropic organizations, because they would change dramatically the reported financial condition of a large number of nonprofit organizations, even though the underlying financial flows will not have changed. In the long run, the proposed changes may obscure or provide misleading information to those seeking to understand the NPO financial statements.

Much of the discussion surrounding nonprofit accounting concerns specific items, e.g., depreciation of fixed assets or consolidation reporting. The arguments on either side of the debates are laden with implicit values and assumptions which are often in conflict. Frameworks to resolve the issues by identifying defining criteria or categories of nonprofit organizations and their components are often absent. The frameworks that are used are often onedimensional, i.e., based only on the nature of the transactions.2 What is needed is a framework that recognizes the nature of the organization, of its transactions, of its goods and services, and of the relationship between its revenuegenerating events and the goods or services provided. A framework which addresses only one of these dimensions will not capture the rich variety of activity in nonprofit organizations. One-dimensional frameworks run the risk of creating meaningless categories which will not provide the readers of financial statements with the information they require for informed decisions.

Very recently, however, a new framework for prescribing accounting policies has been suggested by Professor Haim Falk.3 We believe that Professor Falk’s framework provides the basis for resolving the dispute as it relates to individual nonprofit organizations by examining the nature of each nonprofit organization and the types of services that it performs. His framework explicitly addresses two of the four criteria mentioned above and implicitly addresses the nature of the transactions. We have added the fourth dimension to his framework by dividing one of his categories into two to encompass the revenue-generating component.

Background

Nonprofit organizations come in many types and sizes, ranging from small specialized clubs to international social service agencies. They provide a variety of goods or services for widely disparate societal groups.

The accounting practices used by the various types of nonprofit organization also vary because they have developed in different types of organization according to the needs of the organizations’ managers, benefit groups, and funders. The development of accounting practices along “industry” lines parallels that in the private sector, wherein accounting policies for a gold mine differ considerably from those for a farm. Although there are substantial differences in accounting amongst industries in the private sector, the differences between the various types of nonprofit organization are even greater.

This diversity seems to disturb many professional accountants. Familiar with accounting in the private sector, accounting standard-setting bodies in North America have looked askance at the variety of generally accepted nonprofit accounting practices and have undertaken to limit sharply the alternatives that will be acceptable in order for a nonprofit organization to receive an unqualified audit opinion. Both the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants and the Financial Accounting Standards Board are attempting to impose accounting policies on nonprofit organizations that are appropriate for the private sector but are of dubious value for the nonprofit sector.4

The attempt to force nonprofit organizations into a mold made for profit-oriented business is of concern to many nonprofit organizations, and is also of concern to the agencies, foundations, individuals, and government ministries that fund them. As Professor Rosen pointed out in his article,s the proposed standards will decrease the usefulness of financial information for most arts and social services agencies while simultaneously increasing the cost of providing the required information.

If the proposed standards are not acceptable for a large proportion of nonprofit organizations, what guidelines are there for accounting for nonprofit organizations? Unfortunately, there has not been a systematic framework to help organizations, their auditors, or the users of their financial statements to determine what types of accounting policies are appropriate.

The lack of a general framework is troublesome because the wide variety of accounting policies that are used in nonprofit organizations gives managers a dizzying choice of ways to report the financial results of their organizations’ operations and their financial condition at any particular time. Using one set of accounting policies can show a substantial surplus while using others can result in a significant deficit. Funders, contributors and auditors all need a framework so that they can have some assurance that the organization is not manipulating its financial results. That is why Professor Falk ‘s proposed framework is so welcome.

Accounting Issues

The major accounting issues that are the current subject of debate include:

1. Entity reporting: should an organization report all of its financial activities, regardless of source, program or restriction, all together as a single combined entity instead of reporting separate!y by fund or program?

2. Expense accounting: in its statement of operations should an organization report items of expenditure only when they are used (i.e., on an expense basis) or when the resources have been committed to acquire goods and services (i.e., on an expenditure basis)?

3. Depreciation: should an organization charge just a part of the cost of acquiring long-lived assets to each year that the asset is used (expense basis) rather than to the year that it is acquired (expenditure basis)? Although this issue is related to the broader issue of expense accounting, its importance merits separate attention.

4. Fixed asset capitalization: should fixed or capital assets (such as buildings and equipment) be reported on the organization’s balance sheet (capitalized) or be treated as an expense for the period? This issue is related to the issue of depreciation, but can be separated because capitalized assets do not necessarily have to be depreciated.

5. Recognition of the value of volunteer services: should the value of the time of volunteers be recognized as a donation offset by an identical expense or an expenditure for services rendered?

6. Recognition of capital inflows as revenue: should revenue received for the acquisition of capital assets be recognized as revenue in the statement of operations?

While there are other issues under discussion, these six are the most important. Their resolution will profoundly affect the way that financial results are reported by any nonprofit organization.

The Falk Framework

The framework proposed by Professor Falk is based on a two-dimensional classification. The first dimension is the nature of the organization. Nonprofit organizations can be classified as either clubs or nonclubs (e.g., charities). Clubs are organizations that exist primarily to serve members who pay dues or fees to enjoy the benefits of membership. Thus there is a concurrence between the providers of the organization’s funding and the primary beneficiaries of its goods and services. In nonclubs, in contrast, the beneficiaries of the goods and services are substantially independent of the sources of funding.

The second dimension is based on the nature of the goods and services that the organization provides. Goods and services can be classified as either private or collective. Private goods are those that benefit individuals rather than groups and that are of limited availability, i.e., those who benefit from the resource or service will prevent others from benefiting because the resource is limited (e.g., beds in a hostel for the homeless). Collective goods, on the other hand, are those that benefit groups and that are available to all within the group (e.g., a recycling awareness program).

Both clubs and nonclubs can provide both private and collective goods or services. For example, a trade union (a club) can provide private benefits such as strike pay for its individual members while also providing collective services for its membership (and for those outside of its membership) through a public campaign for greater employee protection. Similarly, a nonclub may provide private goods (e.g., visiting nurse services) and collective goods (e.g., substance abuse education).

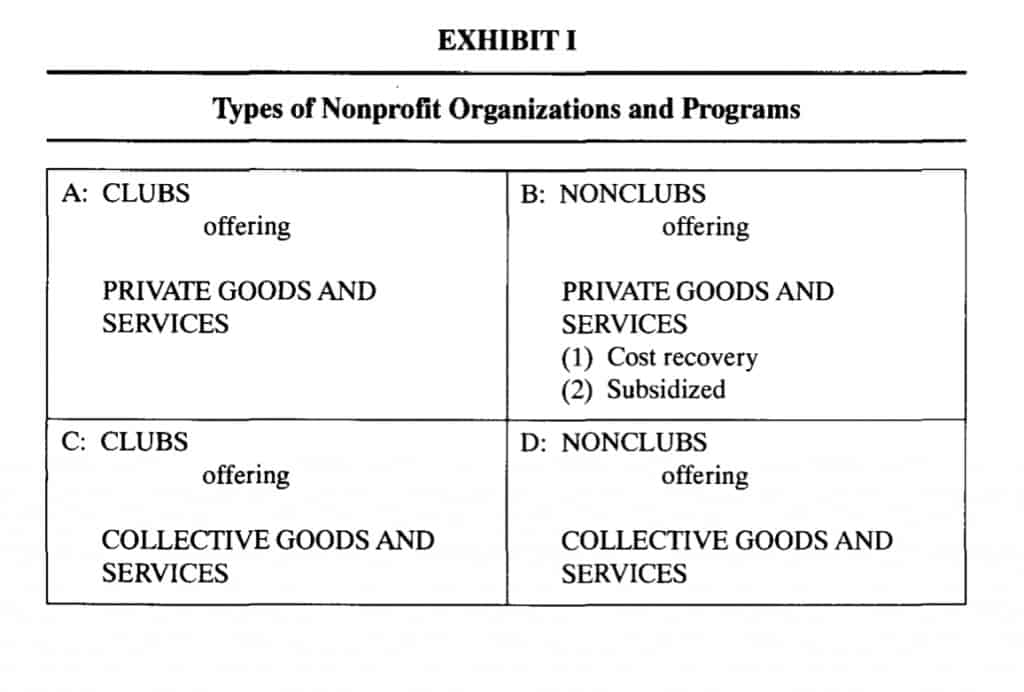

Using the two classifications, we can construct a 2 x 2 matrix as shown in Exhibit I (page 40). The upper row (cells A and B) represents private goods, while the lower row (cells C and D) represents collective goods. Vertically, the left column (cells A and C) represents private goods and services while the right column (cells B and D) represents collective goods and services. Each nonprofit organization will normally fall only within one column (that is, it will be either a club or a nonclub), but the individual programs offered by the organization may fall into either the private or collective row.

There are grey areas, of course, particularly in distinguishing between private and collective goods and services. A soup kitchen run by a nonclub is a private good because capacity is limited and provision of services to some will deny those services to others. But if funding is adequate and capacity is sufficient, the soup kitchen may be available to all comers and, in effect, be a collective good. As we will demonstrate later, however, the cell distinction is more important for some dimensions than for others.

Accounting for Clubs vs. Nonclubs

It is the nature of clubs that they perform services for a membership group (although others outside the membership group may benefit from the club’s collective goods and services), and that the membership group provides all or most of the resources of the organization (although outsiders may pay for certain private goods). Membership is transferable; members may join or leave the organization. Funds within a club are usually transferable at the option of the members or their elected representatives; fund restrictions are normally voluntary for major aspects of the organization’s activities.

Club members expect a return for their dues, fees, and contributions. They will enjoy a return only during their period of membership, and in effect they will want to know whether they “got their money’s worth” from the activities of the club during their membership period. If a club incurs costs this year that will benefit members in future years, this year’s members will want their current dues to support only the benefits they receive this year; they don’t want to pay for others to enjoy benefits in the future. Therefore, clubs should use expense accounting rather than expenditure accounting, so that the financial resources provided by the members can be matched to the goods and services provided to them in any one year.

Similarly, fixed asset capitalization and depreciation is appropriate for clubs. The efficiency of the club’s activities for the period must be matched to the resources provided by the members. Funds for the replacement of fixed assets often must be recovered from the operating revenues of the club.

Since resources are usually transferable in a club, entity reporting is appropriate. Revenue from capital campaigns should be reported as revenue, because even though the contributions may have been intended explicitly for capital purposes, the transferability of resources enables the club (or its board) to redirect the funds if circumstances warrant.

When volunteer services are provided by club members, they are often of a kind that would otherwise have to be purchased. Therefore, the value of volunteer services would be recognized both as revenue and expense. Accounting for volunteer services should follow the accounting for donated goods and services normally applicable to nonprofit organizations: if the organization would have purchased the good or service had it not been donated, then the value of the good or service should be recognized in the accounts.

Nonclubs, on the other hand, are subject to a much different set of circumstances. The resource providers are different from the beneficiaries of the organization’s goods and services (with an exception to be discussed below) and the funding agencies and donors are not concerned about receiving a direct benefit, but rather are concerned with how the organization spent the money they gave it. The stewardship reporting responsibility of the organization requires accounting for the flow of funds rather than the allocation of costs. Indeed, inter-period allocation of costs (such as depreciation) will actually reduce the effectiveness offinancial reporting for the donors (funding agencies, foundations, governmental ministries and individuals) because it will not be clear just what happened to the money donated during the year.

The need for stewardship reporting for donated funds also leads nonclubs away from entity reporting. Funding agencies usually tie their financial support to specific programs rather than to the organization as a whole, and the funders need to see the disposition of their programmatic resources rather than the results of operations for the organizational entity as a whole. Programmatic reporting on an expenditure basis serves the funders’ needs much more effectively than does entity-basis expense accounting. Similarly, the recognition of capital funding as operating revenue and the depreciation of fixed assets misstates both revenues and expenditures for nonclubs.

Most nonclubs exist as volunteer organizations. If there were no volunteers, the organization could not, or would not, exist. Therefore, there is no value to reporting the value of volunteer services; volunteers’ time would not be purchased if it were not donated.

Nonclubs are usually resource-driven, and the level of resources is not normally responsive to the demand for goods and services, even for private goods. Therefore, the level of goods and services provided by a nonclub is not related to the overall cost of the services (i.e., on an expense basis, including depreciation) but is related to the level of funding resources provided by the funders.

An exception arises when a nonclub provides private goods or services on a cost-recovery basis. In such circumstances, the nonclub will need to recover the full cost of providing the goods or services, and expense accounting is appropriate for that program. When it is necessary to recover the cost of fixed assets (or the portion thereof) that are being used for the self—supporting private good, then depreciation accounting is also appropriate.

Therefore, the accounting for private goods and services provided on a costrecovery basis by nonclubs will be expense based, similar to the accounting used by clubs, but only for those specific activities. The accounting for programs delivering collective goods and for those delivering private goods on a subsidized (and, therefore, fixed revenue) basis will continue to be expenditure based.

Summary

The relationship between the resource provider and the beneficiary of goods and services is a crucial one in determining the appropriate financial accounting policies for a nonprofit organization. Recent attempts to standardize financial reporting for all types of nonprofit organizations are doomed to failure because they fail to recognize this very important distinction.

Another distinction that has not yet been recognized by the professional accounting bodies is the distinction between private and collective goods and services. Current efforts to standardize nonprofit accounting fail to recognize that it is intrinsically impossible to measure the unit costs of collective goods and services because there are no output measures, only input or process measures. For example, a drug awareness campaign may produce several pamphlets, television commercials and seminars. Although we can measure the cost of such activities, none of these goods or services is the intended product or “outcome” of the campaign. They are all (process) tools to achieve the intended outcome-increasing awareness of the problems associated with drug abuse-so the effectiveness of the campaign cannot be measured by the unit cost of the processes or inputs. Accounting that focuses on determining the cost of services rather than the disposition (or stewardship) of resources therefore serves the needs of neither nonprofit organization managers nor their funders.

Professor Falk’s newly developed framework for nonprofit accounting does provide a basis for determining the most appropriate accounting policies, depending on {1) the type of organization and (2) the type of goods and services. Our additional component addresses the relationship between the revenue-generating process and the goods or services provided and further elaborates his model. An important test of Falk’s framework, extended by the revenue criteria, is that it does correspond with the preponderance of established practice that has been built up over many years in the nonprofit sector while still providing accounting guidance to managers, auditors and users.

The implications of Falk’s framework for the six major accounting issues identified earlier in this article are summarized in Exhibit II (page 41). Basically, clubs need expense basis accounting and entity reporting, while nonclubs need expenditure basis accounting and programmatic reporting.

In an article in CA Magazine we have discussed the new framework’s implications for managerial control in nonprofit organizations.6 For philanthropic organizations that are providing funds to nonprofit organizations, however, it is the financial reporting aspect that is most pressing.

If the financial supporters of nonprofit organizations want to prevent the degradation of financial reporting for nonclubs providing collective goods and services and subsidized private goods and services, they should be aware of the efforts now underway to force nonclubs to report on the same basis as clubs and thereby to obscure the stewardship reporting that most funding agencies and foundations require.

FOOTNOTES

1. For information about the proposed changes see A.L.S. Rosen, “CICA Exposure Draft: A Comment”, (1992), 11 Philanthrop., No.2, pp. 40-45.

2. Robert Anthony, Should Business and Nonbusiness Accounting be Different? (Harvard Business School Press, 1989); and Financial Accounting in Nonbusiness Organizations: An Exploratory Study of Conceptual Issues (FASB, 1978).

3. Haim Falk, “Towards a Framework for Not-for-Profit Accounting”, Contemporary

Accounting Research, Spring 1992, pp. 468-499.

4. In Canada, the standard-setting group is the Accounting Standards Board of the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA). In the USA, the standard-setting group is the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), an independent board that relies on the support of the Securities and Exchange Commission and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants to give its pronouncements force.

5. Supra, footnote 1.

6. Thomas H. Beechy and Brenda Zimmerman, “Nonprofit Accounting: The Issue”, CA Magazine, November 1992.

EXHIBIT I

EXHIBIT II

Financial Reporting by Nonprofit Organization and Program Type

Types A, C, and B(1):

A: Clubs offering private goods and services

C: Clubs offering collective goods and services

B(l ): Clubs offering private goods and services on a cost-recovery basis

Should use the following financial accounting policies:

1. Entity reporting. (All activities combined into a “total” column.)

2. Expense accounting. (Costs recognized in the period in which their benefits are realized.)

3. Depreciation. (Cost of capital assets should be allocated to the periods that benefit from their use.)

4. Fixed asset capitalization. (Capital assets should be recorded on the balance sheet and depreciated.)

5. Volunteer service recognition. (The value of volunteers’ time should be shown as both revenue, i.e., donation, and expense.

6. Revenue recognition of capital contributions. (Donations for the acquisition of fixed assets should be reported as revenue.)

Types B(2) and D:

B(2): Nonclubs offering subsidized private goods and services

D: Nonclubs offering collective goods and services

Should use the following financial accounting policies:

1. Programmatic reporting. (Operating results for the year should be reported by major program activity and not combined.)

2. Expenditure accounting. (The statement of operations should show amounts expended during the year to acquire goods and services rather than amounts used during the year.)

3. No depreciation. (The cost of acquisition of capital assets should be reported in the capital fund in the year of acquisition. No charge to operations should be made in the years of use.)

4. Fixed assets should not be capitalized for depreciation. (They may be capitalized to indicate the resources available and to improve asset control.)

5. Volunteer services should not be recognized as revenue and expenditure. (The value of volunteer services may be disclosed outside of the financial statements.)

6. Capital donations should not be recognized as revenue. (Capital grants and the proceeds from capital campaigns should be segregated in a capital fund and not combined with program operations.)

THOMAS H. BEECHY and BRENDA J. ZIMMERMAN

Faculty of Administrative Studies, York University, Toronto