Introduction

Statesmen, politicians and journalists have always enjoyed painting comparative word portraits of the United States and Canada showing a strong family resemblance.Both nations use English as the dominant language of commercial and social life; both have drawn immigrants from around the world to settle virgin wildernesses; and both are democracies in the western tradition. Their neighbourly co-existence during the past 100 years or more, while marred by an occasional economic or geopolitical squabble, has been, on the whole, amicable. A few years ago, when Canada’s National Film Board published a photographic essay on relations along the 5000-plus miles of our mutual border, no one found it odd that the resulting volume should be titled Entre Amis-Between Fn”ends.

In both the United States and Canada, the voluntary sector has played a key role in national social development since colonial times. Both nations have large numbers of organizations which, for taxation purposes at least, are classified as charitable. In both countries, the domestic, economic and political crises of recent years have threatened the health, or even survival, of those organizations. Superficially at least the two voluntary sectors seem to share both historic roots and contemporary roles. Deeper probing leads to questions.

How similar really are the roles of the voluntary sectors in the United States and Canada? Where they are similar and parallel, do they spring from the same roots and are those roots sustaining them as in former times? Where they differ, what historical factors have contributed to the divergence? More importantly, what can be learned by each sector from the similarities and differences which emerge from a comparative review, which might strengthen both as they struggle to accommodate and capitalize on the trends emerging for the next decade?

This paper will trace the development, and examine the roles, of the voluntary sector in both countries. Similarities and differences will be highlighted and a number of issues and questions will be identified for future enquiry.

Comparisons will sometimes be difficult because of the differing definitions and categories used in data collection in the two countries. Both nations have difficulty defining the voluntary sector and its parameters. Nevertheless, both recognize the diversity, creativity and responsiveness of their voluntary sectors (Neilsen, 1979; Martin, 1985*) and generally acknowledge that the sector exists independently of government and business (Levitt, 1973; Joyal, 1984) rather than “at the frazzled edges of the other two sectors” (Payton, 1985). While the technical parameters for the sector may differ between the two countries, both include a wide range of institutions such as religious organizations, colleges and universities, foundations, hospitals, day-care centres, youth organizations, advocacy and neighbourhood groups, and cultural organizations. In Canada, the sector also includes large numbers of voluntary sports and recreational associations. On both sides of the border, the rationale for inclusion or exclusion within the sector appears, in general, to be whether the organization is “public regarding” or “private regarding” in its purposes and intent (Gamwell, 1985).

Development of the Voluntary Sector in the United States In a recent statistical overview compiled by the Independent Sector (Hodgkinson and Weitzman, 1984) some 785,000 organizations were reported in the United States independent sector in 1980. These included independent schools, churches, research organizations, foundations, civic and social welfare organizations, voluntary organizations, and advocacy organizations serving educational, scientific and religious or other charitable purposes. The sector’s share of national income rose from 5.1 per cent ($62 billion) in 1974 to 5.5 per cent ($123 billion) in 1980. In 1980itaccountedfor 7.5 percent($116 billion)of the national total of earnings from work, and 9.2 per cent ( 10.2 million) of total employment. In comparison, business accounted for 80 per cent of national income in 1980, up from 79 per cent in 1974. Government’s proportion of national income declined from 15 per cent in 1974 to 14 per cent in 1980 (Hodgkinson and Weitzman, 1984). (All figures relating to the voluntary sector include the estimated value of volunteer time.)

Several scholars (Hall, 1982, 1985; Katz, 1985; Levitt, 1973; Neilsen, 1979; eta/.) have commented on the fluctuating levels of government participation in the voluntary sector since colonial times. In the New England colonies, there was a thorough integration of church and state and the economy and the private voluntary sector because the religious and political views of many of the settlers had been infused with the spirit of the Enlightenment. (Neilsen, 1979) Intellectually, the Puritan forefathers did not separate the roles of church and state. They were also, by necessity, pragmatists in the harsh and alien land: they brought to every task whatever resources were at hand in whatever combination seemed likely to work. Throughout the 1600’s and 1700’s the governments of the northeastern colonies regularly granted business charters, regulated wages and business practices, and voted tax or other monies to be used for the care of the sick, to encourage science, and to create colleges to educate the clergy and others. (Hall, 1982) For example, Harvard College was established in 1650 by the Massachusetts Bay Colony—a homogeneous, theocratic community of Calvinist Puritans-to produce a learned ministry and was financed through rents from the Charlestown ferry and the “colledge com”tax levied annually onevery family in the colony. (Neilsen, 1979) By the time of the revolution this comprehensive view of the role of government was well established.

The history of the southern colonies was quite different. Southern society developed along traditional and parliamentary rather than ultra-democratic and populist lines. (Hall, 1982)

As the new republic matured politically, the descendants of the northeastern forefathers became Federalists-imbued with the belief that the rich are stewards of the souls and bodies of those less fortunate-those “not chosen”, in Calvinist terms. In states where these views were dominant, private charity was regarded as a public duty and testamentary trusts which were designed to build charitable endowments were perceived as being desirable instruments for discharging that duty. In keeping with the tradition of”noblesse oblige” they were governed by elite corporate boards and early court cases established that government had no right to interfere with such private contracts or “corporations”. (Hall, 1982)

Descendants of the southern forefathers become Jeffersonian Democrats, whose views were more closely attuned to the principles of the English parliamentary system, i.e., majority rule through a “parliament” elected on a restricted franchise. In the south, private testamentary trusts and corporate boards were not encouraged by facilitating legislation (Hall, 1982) because it was believed to be the right of “society”, in the form of the governing elite, to provide direction and initiatives in all areas of public life. For example, a state university was established in Georgia by 1783, and in North Carolina by 1795. (Neilsen, 1979) In the years leading up to the Civil War, these”democratic”views gained dominance, particularly after the election of Andrew Jackson, when militant demands that government should offer “equal protection and equal benefit” to all the people became a theme of public debate. After the Civil War, this egalitarianism was reinforced by immigrants who had been exposed to European socialist theories, and by a populist countercurrent which was becoming more vigourously concerned with ensuring “freedom from”arbitrary rule and excessive government power rather than with governments’ “freedom to” shape public policy. (Neilsen, 1979)

The liberal theories of Locke, Montesquieu, John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer were now exerting great influence in all democratic societies and were reinforced by the rise of rich and influential entrepreneurs when the industrial revolution resulted in the development of the joint stock company which had almost unlimited potential for the accumulation of private wealth and power. (Hall, 1982; Neilsen, 1979)

Katz ( 1985) notes that prior to the late 19th century, individual benevolence by the rich (such as a Carnegie or a Rockefeller) was exercised in traditional charitable terms. Charity was traditionally defined as an effort, arising from a sense of religious obligation, to alleviate individual cases of physical illness, poverty, ignorance and suffering of other kinds. It was seen to draw its strength from a one-on-one relationship of donor to recipient. (Payton, 1985) During the Gilded Age, roughly from 1810-1920,philanthropy began to develop as an urge to change society by ridding it of precisely those ills which charity soughtto ameliorate. (Katz, 1985) Where charity sought to cure the sick, philanthropy tried to eradicate the virus or conditions which caused the disease. Katz (1985) argues that this philosophical transition was logical for men who had created vast fortunes using scientific techniques to monetize natural resources, and who had developed new organizational strategies so as to apply labour most efficiently to this task. The growth of private foundations in the United States was a direct result of this major transformation of benevolence. As the private foundations matured during the 1920’s and the 1930’s, their philanthrophy became more institutionalized, less interested in continuing subsidies than in setting out substantive agendas for research. (Katz, 1985)

McCarthy’s (1985) studies of Chicago volunteers from 1850 through the 1930’s reinforces Katz’s views of the social philosophy of benevolence in the United States voluntary sector during this period. In the decades following the Civil War, volunteers moved from providing essential social welfare services to the provision of more exclusive and segmented philanthropic assistance. By the 1920’s, professional “helpers”-social workers, managers, etc.-had placed themselves between volunteers and their clients, as the private foundations were becoming increasingly institutionalized and research-oriented. By the late 1920’s, volunteers were increasingly consigned to the fund-raiser’s role. (McCarthy, 1985)

The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Second World War brought crises of such magnitude that private philanthropy could not cope. Government programs, which looked something like philanthropy, were initiated and continued to grow through the 1950’s and early 1960’s. (Katz, 1985) It is only with the global and domestic economic crises of the 1970’s and 1980’s that public attitudes have begun to swing back toward a Federalist position, i.e., that government should withdraw from its leadership position in the provision of charitable and philanthropic services, and that responsibility should be more equally shared with the voluntary sector.

This new attitude is unlikely to be any more permanent than previous swings of the pendulum. Even the brief history outlined above suggests that in due course there will be another swing toward the Jeffersonian Democratic view. Whatever the prevailing wisdom, the history of the voluntary sector in the United States has been more or less one of collaboration between government and the private sector. Crucial to the success of that collaboration has been the view that the voluntary sector, while a partner with, and beneficiary of, government, has an initiatory, stimulative and critical function in philanthropy. (Neilsen, 1979) The flexibility which permits private charity to be both collaborator and countervailing force has been a primary strength of philanthropy in the United States. When the Jeffersonian Democrats prevailed, the philanthropic sector has been able to operate as a stimulative agent to government, assisting both in thedevelopment of public social policy and in the direct delivery of social welfare and cultural services. In Federalist times, the sector has been able to draw strength and resources from its religious roots, and to establish alliances with the corporate philanthropic activities of the private sector.

What does this mean for a discussion of the roles of the voluntary sector in the United States? Much of the literature on such roles (Bremner, 1985; Hall, 1982, 1985; Levitt, 1973; Neilsen, 1979; Payton, 1985) is concerned with providing a static “snapshot” of sectoral activities at a given period in history, or concentrates on describing the roles of the various constituencies and motivations for their acceptance. (Payton, 1985) A more useful view of the sector can be achieved by developing a scalar matrix format to account for the historical fluctations. (Figure 1)

The vertical axis indicates three primary divisions in role activities:

(a) service/product provision-implementation and delivery of programs within prescribed or approved parameters;

(b) mediation-facilitation of community participation in public policy development; (Bremner, 1985; Berger and Neuhaus, 1977) and

(c) advocacy/social change-influencing public policy development by lobbying, demonstrations, litigation.

The horizontal axis represents three potential “targets” of sectoral role activity:

(a) individuals-discrete or collective groupings which might be beneficiaries of role activities;

(b) social institutions-organizations or mandated entities which do, or could, provide venues for sectoral role activities; and

(c) environment/society-more general venues for planned intervention or change, e.g., broadly-based movements against pollution or for peace.

The activites of the various sectors and their interaction with the “targets” are designed to achieve intended social ends. These social ends could be the enlargement (or stretching) of institutional and individual capacities. They could be the provision of increased welfare benefits or attempts to respond to, or fill, other human needs. The desired end may also be the initiation oflimited, or even widespread, change.

Historically, the distinguishing features of role activities in the voluntary sector have been an active approach to “targets” and the ability to respond to human needs and values-features which have arisen because of the flexible and permeable structure of the sector.

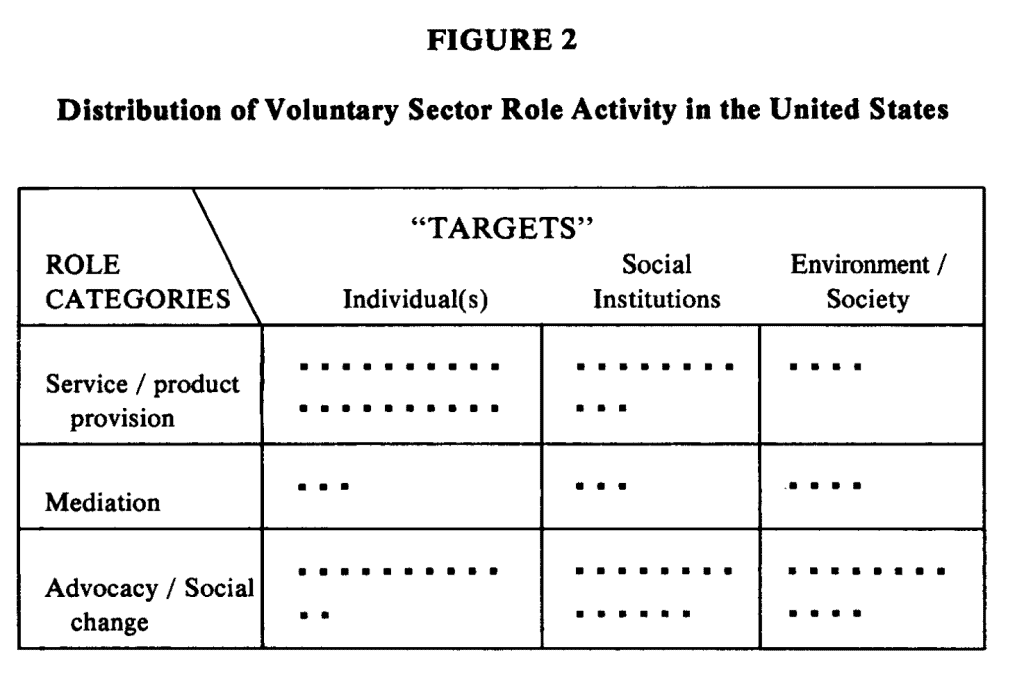

If one were to attempt to fill in the cells of the matrix, Row 1 (service/product provision) would probably have the heaviest cell population (particularly in Column 1), in whatever historical period for which we develop a “snapshot”. Row 3 (advocacyIsocial change) would have a young cell population, emerging primarily since the early 1960’s. Row 2 (mediation) would probably have the smallest population and a population that has been largely scattered since colonial times. While government-voluntary sector collaboration has been more or less continuous in the United States, the voluntary sector has usually been rhetorically uncomfortable with a close or complementary relationship. This discomfort prevents full development of a mediating role.

The Sector and Its Development in Canada

Compared to the economic value of its counterpart in the United States, the voluntary sector in Canada appears small. Nevertheless, “humanistic” serviceseducation, health care, social welfare and cultural expenditures-consumed about 31 per cent ($70 billion) of the country’s national income in 1980. (Martin, 1985) About a third of that money ($25 billion) was transferred directly by the federal and provincial governments to individual Canadians in the form of old age pensions, unemployment insurance benefits, welfare assistance, health care payments, etc., while about 20 per cent of national income ($45 billion) was handled by humanistic organizations governed by corporate boards: hospitals, universities, schools, family service agencies, churches, theatres, fraternal societies, etc. This compares with the 5.5 per cent of national income generated by the parallel sector in the United States. The Canadian voluntary sector in 1980 employed more people than were on the direct payroll of all levels of government combined. (Martin, 1985)

In part, the large voluntary sector in Canada reflects a strong historical tradition of community participation in the governance of voluntary agencies which primarily deliver services, and assist in policy development, for government. Consequently, there is a very strong weighting toward government in the overall funding of voluntary sector activities. In 1980 governments contributed more than six times as much to humanistic services as did individual Canadians. In the fields of education and welfare, state responsibilities by long tradition, the weighting was 13:1 in favour of public sector funding; in health care, the ratio was 4:1; and in culture—a category which embraces recreation and religion as well as the arts—the ratio was 1.2:1. (Martin, 1985)

Martin ( 1985) estimates that private sources spent $9 billion on humanistic services in 1980. Two-thirds of this ($6.6 billion) came from private expenditures by individuals directly for goods and services received. Private financial assistance for welfare totalled $1.6 billion; tuition fees paid by individuals and other educational expenses cost $1 billion. Expenditures for admission to cultural events totalled $650 million. The balance supplied by the private sector ($2.3 billion) came in the form of charitable donations and gifts from all nongovernment sources and voluntary donations made by individuals directly to voluntary sector organizations which totalled $1.88 billion. Business and corporate cash gifts and contributions came to $260 million in 1980, roughly onetenth the amount donated by individuals. Foundations and endowments accounted for the remaining $100 million.

Martin ( 1985) also notes: about 60 per cent of the total of charitable donations was received by religious organizations; about 13 per cent went to social welfare organizations; 10 per cent to hospitals and health-related institutions; 11 per cent to schools, universities and teaching institutions; and seven per cent to the support of cultural and community causes, such as the arts, libraries, conservation and preservation, recreation, etc.

Martin ( 1985) presents the most comprehensive historical overview of the development of the voluntary sector in Canada to date. He maintains that, if the provision of human services in a single nation during a particular period of time is examined and the analysis duplicated in delivery systems in other societies in the Western world, a common pattern of change emerges which can be described in four stages of interaction and financing:

(a) Stage !-individual to individual. Society is characterized by a high degree of personal involvement, interaction and responsibility for the delivery and receipt of humanistic service;

(b) Stage Il-individual to institution. Deliverers of human services institutionalize in urban concentrates, e.g., hospitals, schools, museums;

(c) Stage III-collected individuals to institutions. Demand for human services increases, causing organizations to step up their appeals for operating funds. This is followed by recognition that demands for service funded from voluntary financial resources must be balanced against the need for financial resources to sustain the organizational infrastructure so the need for public support is acknowledged; and

(d) Stage IV-state to institutions. Society as a whole decrees that its members shall be provided with an appropriate level of health care, education, cultural enjoyment and social well-being which become public, not private, goods.

Martin ( 1985) contends that Canadian society has progressed towards Stage IV in several key sub-areas of the voluntary sector, and that this is consistent with its historical development as a nation. Quebec (then New France and later Lower Canada) was founded in 1608 and for 150 years Canada was French in language, customs and culture. In the area of human services, the new colony began at Stage IV, because the colonists depended on France not only for defence and trade, but for the provision of health, education and welfare services. The state established a Bureau of the Poor in 1685, whose aim was to solve social problems as well as to provide an outlet for Christian charity. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Crown had accepted responsibility for the aged, crippled and orphaned, and for the care of foundlings, and the Roman Catholic Church was an integral intermediary in the dispensing of Crown funds for human services.

British rule, imposed after the fall of Quebec in 1759, meant that Canada reverted to Stages I and II, with settlers assuming personal responsibility for their own welfare. The churches, which did not receive the same level of financial aid from the British as from the French Crown, provided fallback resources. In the next 100 years before Confederation, Canada’s voluntary sector gradually took shape: hospital care would remain at Stage II; medicine at Stage I; education would move directly to Stage IV; and social welfare, in much of the country, would remain largely at Stages I and II. (Martin, 1985) Cultural activities were provided and financed by individuals or the churches.

Regional differences emerged during this gestation period. While residents of Upper Canada relied on mutual aid and those in Lower Canada continued to call upon the Roman Catholic church, the Atlantic colonies initiated a system of state relief to combat urban poverty which was supplemented by the efforts of private charitable organizations. Health care development followed a parallel path, with religious auxiliaries of the church co-ordinating health care in Lower Canada, while military health-care facilities were converted for public use in Upper Canada.

Education, as usual, provoked some of the most spirited de bate over the respective financial roles of the private and public sectors.In a country which today supports almost no private colleges or universities, it seems difficult to believe that all universities in Upper Canada were exclusively denominational until 1853. Canada’s first English university, the University of King’s College in Windsor, N.S., was financed in a way which provides insights into the delicate blending of state, church and private funds which later characterized higher education in Canada. The seed money was voted by the Nova Scotia House of Assembly because it was feared that, without an indigenous college, Canada’s future leaders would attend universities in the United States where they would be taught republican ideals. (Martin, 1985) The British Crown also provided money, as did the Anglican Church. In Lower Canada, the School Act of 1846 decreed the union of religion and education and provided for two state-aided school systems, Catholic and Protestant. The role of the state was chiefly that of providing money and establishing lists of acceptable textbooks. After Confederation in 1867, this checkerboard pattern of educational development continued; the provinces were given responsibility for health and welfare and education was also delegated to the provinces as a concession to the French majority in Quebec. (Martin, 1985)

During the first 60 years of Confederation, not much changed. Personal service, altruism, and philanthropy were encouraged, and human service organizations federated for private fund raising through the establishment of the Community Chest. State aid was supplied largely by local governments (which were closest to the people) and provincial and federal governments expressed little enthusiasm for invading the human services sector. (Martin, 1985) A fundamental realignment between private and public funds occurred with the Great Depression. The desperate plight of many Canadians during this period led to a number of sweeping changes on the political and public policy front: the establishment in 1933 of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (forerunner of the present New Democratic Party) as a moderate democratic socialist party; the passage of legislation establishing a federal unemployment insurance program and establishment of a national employment service in 1940; and legislation in 1944 which authorized a national family allowance scheme and a federal Department of Health and Welfare. (Martin, 1985)

As a result of the greatly increased demand for human services during the Depression, many of them became publicly administered and financed. Health care provides a dramatic example. In the Depression the Saskatchewan government paid doctors a salary to persuade them to remain in areas hard hit by the drought. By 1957, the federal government had introduced a cost-shared hospital insurance program and, in 1962, Saskatchewan introduced a universal publicly funded health care program. A nationwide program followed in 1968. Education and culture experienced similar dramatic shifts to public support during the postwar years.

Now, after almost four centuries of development, Martin (1985) maintains that Canada has come almost full circle in the delivery ofhuman services.During the first 150 years, there was the aristocratic welfare state of New France, of necessity dependent on the French Crown for its resources. From 1758 to 1867, churches and individual initiatives conceived, created and financed the schools, hospitals, welfare and cultural organizations that were needed to serve an expanding population-with government providing moral support but little money. From 1867 to the late 1920’s, philanthropy and personal service flourished, but demand began to exceed the supply of voluntary resources so people grouped together to raise funds and to approach local governments for supplementary financial support (Stage III). Since the early 1930’s, Canada has moved toward Stage IV, at first by necessity, then by choice. Voluntary institutions-hospitals, universities, welfare and cultural organizations-are still controlled by individuals, following the tradition of the foundation years because even though governments controlled the flow of funds, they were increasinagly willing to share the decision-making process. In all areas of human service except the field of culture, government funds overwhelmed those provided voluntarily by the private sector.

These historical fluctuations in attitude toward the role of the voluntary sector do not, at first glance, seem too dissimilar from the U.S. experience until the past 50 years. Martin ( 1985) maintains that part of this cultural divergence arises from the fact that Canada has experienced its highest rates of immigration much later than the United States. As a former Canadian Minister of State for Multiculturalism noted, “We’re all boat people-except for those native Canadians who got here by foot. The only difference is some of us caught an earlier boat.”

Until the turn of the twentieth century, Canadian society developed in two parallel streams: British and French. Immigration in the early part of this century changed this: by 1930 almost 20 per cent of the population claimed other origins. (Martin, 1985) Immigration was not significant again until the 1950’s, when net migration accounted for roughly 25 per cent of the growth of Canada’s population and, from that point on, there was a sharp decline in the proportion of British immigrants entering Canada. Immigrants came from southern and eastern Europe, and from other Commonwealth countries; most recently, they came, and come, from Asia and South America. Many recent immigrants are from countries well into Stage IV in their delivery of human services and they have little experience with voluntary associations and little sympathy for personal philanthropy. (Martin, 1985)

Among the founding cultures, organizations providing human services enjoy great community prestige and esteem. Among more recent arrivals from other cultures, government funding and “universality” in welfare programs are considered more desirable. (As the recent public controversy surrounding proposed welfare cutbacks in the federal budget indicated, “universality” is now a “sacred trust”.) Canada remains a mosiac, not a melting pot.

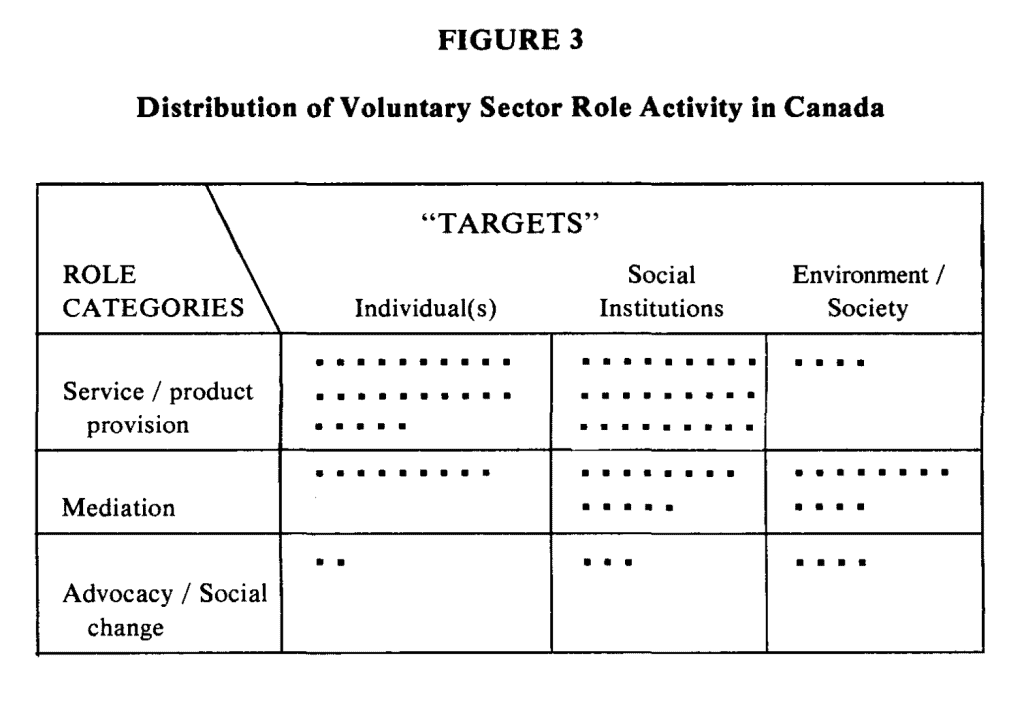

Does the descriptive matrix of the roles of the voluntary sector in the United States also apply to Canada? Yes. Because of the flexibility of the framework and the inclusiveness of its parameters, I believe the matrix is a reliable descriptor for the role and activities of the Canadian voluntary sector. It shows that Canada’s voluntary sector provides services/products, fulfils a mediating role, and engages in advocacy and the promotion of social change. It focuses on individuals, social institutions and broad societal issues and its distinguishing features and desired social ends have the same idealistic overtones as those of its United States counterpart. It is the Canadian delivery system that differs most significantly from the United States and this difference has a substantial impact on the cell population in the matrix.

The most heavily populated cells, again, are found in Row 1. Currently, Canadian governments deliver few direct human services; delivery of services is usually sub-contracted to the voluntary sector. Thus, “private”child and family service agencies may deliver legislatively mandated services, and95 per cent or more of their budgets may come from government support. This sub-contracting phenomenon, in turn, enhances the cell population in Row 2. Because public policy is so often implemented through organizations governed by private boards, the Canadian voluntary sector has historically been able to facilitate incremental change in the public policies relating to human services. (Wolf and Sale, 1985)

Row 3 is more sparsely populated in the Canadian sector than in its United States counterpart. Also advocacy groups are a more recent phenomenon in Canada and do not seem to have had the same impact. In part, this may be because their strong funding and sub-contracting links to government render voluntary organizations toothless when substantive change is required. Or perhaps popular historian Pierre Berton is right: Canadians are more comfortable mediating change through polite discussion than through confrontation or the strident voicing of dissatisfaction with the established order.

The Impacts of Difference: Some Speculation, More Unanswered Questions In both the United States and Canada the role of the voluntary sector is rooted in Jeffersonian or parliamentary democracy. In Canada, these parliamentarian roots have been accentuated by the pattern of recent immigration which has encouraged the development of universality as a cultural value which has been superimposed on the traditional esteem for human services. The Federalist/ Jeffersonian dialogue in the United States has resulted in a more balanced funding pattern which permits more aggressive advocacy and also, perhaps, retains a greater capacity for innovation (although, in Canada, the role of private funding is frequently to underwrite demonstration projects).

The United States sector’s rhetoric of independence, however, acts as a constraint on its ability to act as mediator—a role which can be important if citizens are to feel they are part of the public policy development process. Perhaps—and this is clearly a Canadian view-an enhanced mediation role could obviate some of the need for a strong advocacy role in the United States. There is, of course, in Canada, that heavy dependence on government funding. While this enhances the sector’s role in mediation, it poses the danger that it will be coopted. (Fryer, 1984) The impact of such cultural values as universality and more rigid income taxation structures are other factors which will affect the Canadian sector’s capacity to restore its funding balance in the remaining years of this decade.

How can the two voluntary sectors benefit from a comparative study of their roles? For a start, they are two of the largest voluntary sectors in the Western world and their similarities are strong enough for mutual benefits to come from the sharing of scarce data, particularly as research moves from the merelydescriptive to the explanatory. What impact, for instance, do public conceptions of the sectors’ roles have on giving? Kielty ( 1984) and Martin ( 1985) have begun important research into the motivations of Canadian donors; research in the United States might prove beneficial for both countries.

In several areas of the matrix described above, particularly Column 3, Canadians and Americans share common concerns such as pollution, peace, etc. If information- and data-sharing were more common practice between the two sectors, much could be gained by collaboration in the development of policies and strategies in the overlapping areas. In the voluntary sector, as in other political arenas, problems are no longer respecters of geopolitical borders.

Unfortunately, since mutual knowledge of, and co-operation between, the two sectors, are still in the nascent stage, two difficulties arise when even a modest comparative overview is attempted:

First, with so many role similarities between the two sectors, it is hard to understand or explain (in less than book-length form) why there is no documented history of complementary inter-sector exchange. At best, what can be found is occasional”branch-plant” histories of communication between individual organizational counterparts. The United Way, for example, may develop a training program for its United States boards, which it may “give” to its Canadian counterpart but with the proviso that it must be delivered in the same way in Canada as in the United States—a delivery strategy which may be culturally, politically and programmatically inappropriate for Canada. (Wolf, 1984)

Second, since there are differences between the two sectors in several key areas as well as a history of non-communication, it is well beyond the ability or scope of a paper such as this, which is primarily a review of the literature, to suggest similarities for the exchange of information or strategic collaboration. Exploratory research is now required to define reasonable parameters for inter-sector collaboration. Perhaps the contribution of this paper is to demonstrate such a need and to suggest the direction such research should take.

An agenda for collaboration should be built on the basis of:

• an analysis of the content and comparability of the data bases maintained by both sectors;

• a comparative analysis of umbrella-like mediating structures in the two sectors: between the United States Independent Sector (IS) and the Canadian National Voluntary Organizations Coalition (NVO) and between the United States Council on Foundations and The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy;

• exploratory attitudinal interviews (formal and informal) with key leaders from both sectors; and

• a comparative examination of policy development processes in the two sectors (with exploration of the potential for use of such techniques as a modified Delphi Method in building joint strategies for key issues).

Both voluntary sectors could be enriched by such information. At a time when both the Canadian and United States voluntary sectors perceive themselves to be endangered there is a profitable lesson to be learned from the governmental and business sectors of both countries. They have already learned the value of transborder C<K>peration.

SOURCES CITED

Berger, Peter L. and Neuhaus, Richard J. To Empower People: The Role of Mediating Stntctures in Public Policy. Washington D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1977.

Bremner, Robert H. “Advocacy and Empowerment Movements in Philanthropy Since 1960”. Working draft, prepared for Independent Sector/United Way Institute, History of Philanthropy Panel, New York, March 15, 1985.

Fryer, John L. “How Unions View the Voluntary Sector”. An address to the NVO Consultation, Ottawa, April 2, 1984.

Gamwell, Franklin I.”Why Are Independent Associations Important?”. Working draft, prepared for Independent Sector/United Way Institute Spring Research Forum, New York, March 15, 1985.

Hall, Peter Dobkin. The Organization of American Culture. New York: New York University Press, 1982.

Hall, Peter Dobkin. “Doing Well by Doing Good: Business Philanthropy and Social Investment, 1860-1984”. Working draft, prepared for Independent Sector/United Way Institute Spring Research Forum, New York, March 15, 1985.

Hodgkinson, Virginia and Weitzman, Murray S. Dimensions of the Independent Sector: A Statistical Profile. Washington, D.C.: Independent Sector, 1984.

Joyal, The Hon. Serge (Secretary of State). Untitled address to the NVO Consultation, Ottawa, April 3, 1984.

Katz, Stanley N. “The History of Foundations”. Working draft, prepared for Independent Sector/ United Way Institute Spring Research Forum, New York, March 15, 1985.

Kielty, Frank. “How the Canadian Public Views the Voluntary Sector”. An address to the NVO Consultation, Ottawa, April 2, 1984.

Levitt, Theodore. The Third Sector: New Tactics for a Responsive Society. New York: AMACOM, 1973.

Martin, Samuel A. An Essential Grace: Funding Canada’s Health Care, Education, Welfare, Religion and Culture. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.(Editor’s note:for a review of this study see The Philanthropist, Vol. V, No. 2, p.56.)

McCarthy, Kathleen D. “New Perspectives on the History of Voluntarism”. Working draft, prepared for Independent Sector/United Way Institute Spring Research Forum, New York, March 15, 1985.

Neilsen, Waldemar A. The Endangered Sector. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979. Payton, Robert L.”Major Challenges to Philanthropy”. Working draft, prepared for Independent Sector/United Way Institute Spring Research Forum, New York, March 15, 1985.

Wolf, Jacke. “University Continuing Education and the Voluntary Sector: Meeting Unmet Needs”. Paper presented to the Canadian Association for University Continuing Education, London, Ontario, June 13, 1984.

Wolf, Jacke and Sale, Tim. “Using Network Analysis in Human Service System Planning,” Business Quanerly. London: School ofBusiness Administration, University of Western Ontario, Fall, 1985.

JACKE WOLF

Assistant Professor, Department of Continuing Education, University of Manitoba