Introduction

Charities in Canada are very interested in developing successful planned giving programs. They see their American counterparts raising millions of dollars in such programs and covet their success. When they quickly learn that for technical tax reasons the charitable lead trust and the unitrust cannot be brought across the border, they concentrate on the popular revocable charitable remainder trust which is used with such success in the United States. Unfortunately, there has not been sufficient analysis of the negative impact of Canadian tax laws on that vehicle. When the problems are explained, the tendency is to abandon the vehicle rather than adapt it so that it will work in the Canadian environment.

This paper will examine the impact of Canadian tax and estate laws on the use of revocable and irrevocable charitable remainder trusts. It will propose a new formulation of the features underlying those agreements which would make it easier to use them in Canada and will also introduce a new planned giving instrument which is designed to take advantage of potential donors’ interest in charitable annuities.

Fund raisers reading this paper will complain that it is excessively technical and complex. They will be concerned that their constituencies will never understand these instruments and consequently will never use them. They will be quick to point out that the fundamental rule of fund raising is-Keep It Simple Stupid.

I would nevertheless point out that there are limits on the degree to which a complex subject can be rendered simple. It should also be noted that one reason that planned giving programs enjoy so little success is that they are frequently run on the same relatively familiar marketing principles which govern direct mail fund raising. There is a tendency to overlook the fact that planned giving instruments can result in individual transactions involving $5,000, $50,000 and even $500,000 while direct mail usually results in donations offrom five to 50 dollars. When the rewards are so great, a little effort seems warranted.

It is my contention that while much of your present constituency will fmd plarmed giving instruments too complex, you are likely to find there is an untapped constituency and source offunding which finds direct solicitation too simplistic. These donors may never make an outright donation of $50,000, but they may consider loaning that amount to your charity on an interest-free basis or placing it in a charitable remainder trust. Restricting gifting programs to those readily understood by the “lowest common denominator” reflects badly on the competence of the development department. If, on the other hand, a charity’s constituency dictates simple gifting programs only, it is a reflection on the constituency.This paper is designed to assist development officers in their understanding of various planned giving instruments and the technical, legal and tax advantages and disadvantages of each. This should equip them, like skilled estate planners, to recognize potential pitfalls and opportunities so they can craft the optimum solution for each potential donor. The technical problems and disadvantages of the various instruments can be turned to advantage by recommending an alternative which the donor would not otherwise have considered.

The Great Circle Route

The vulnerability of a will to attack under dependants’ relieflegislation introduces consideration of the revocable charitable remainder trust but concern about income attribution problems associated with revocable trusts often means there is a more favourable response to an irrevocable trust. Certainly, most charities would prefer a present irrevocable charitable remainder trust to a future uncertain testamentary bequest. However, most donors would consider an irrevocable trust only after consideration of the problems associated with bequests. Nevertheless, success in obtaining an irrevocable trust need not preclude a later bequest.

The title “The Great Circle Route” reflects my belief that planned giving instruments should not be used in isolation. A donor should not be invited to select a “revocable charitable remainder trust” out of a list of six different instruments. Nor should charities advertise and promote an irrevocable trust as the only possible solution because the donor may not select it unless he has previously considered, and rejected, the alternatives. By starting with consideration of the will, the development officer and the donor can walk around “the Great Circle” of giving programs and select the most appropriate instrument or combination.

The success of a planned giving program cannot be judged simply by how many donors use such instruments. Donors should be made aware that the various instruments are available and then gradually educated as to their relative merits. In the early stages relatively few will use them, although it is to be hoped the amounts will be large. In any case, the appropriate course is not to gear up to the aggressive marketing of planned giving instruments but gradually to build confidence and awareness. It is only after the development office has successfully employed these instruments with a variety of clients that they should begin marketing them aggressively to the entire donor constituency.

Wills

Most planned giving programs will begin with the soliciting of testamentary bequests. This is the most conventional place to begin as it is easy to convince your constituency that it is necessary for everyone to have a will. The drawback is that the charity must incur its planned giving program costs today knowing that there is a high risk that the testator may never actually make a bequest. Even if the charity is included in the will, there is usually a long period to wait before the testator dies and the charity receives a financial benefit. Many times a codicil is drawn in the interim in which the testator changes the specific charity which is the beneficiary under his will. An even more common problem is that charitable bequests often are conditional upon the testator’s spouse and all his children and issue having predeceased him.

These factors make it very difficult to conduct a testamentary planned giving program on a cost-effective basis. On a purely percentage-return basis, charities should therefore consider as targets the elderly, the unmarried and the bitterly divorced when planning a bequest program. Yet an aggresive appeal to these particular groups may leave the charity vulnerable to charges of manipulation or undue influence. A charity must conduct itself in such a way that it is above any suspicion of surviving relatives that its representative manipulated or unduly influenced the testator into making a specific bequest.

It is important to remember that the relatives of the deceased will often be hostile to the charitable interests of the testator since, if the gift to charity could be set aside, they would benefit through the other terms of the will or upon intestacy. The testatoris no longer around to vouch for the conduct of the charity’s representative or defend his estate from his relatives. Not surprisingly, the wills which have the greatest potential for a financial return are the very ones which are most vulnerable to attack.

Dependants’ Relief Legislation

Every province has legislation allowing dependants of a testator to apply to the court to vary a will if they do not feel there has been adequate provision for them. In British Columbia it is the Wills Variation Act1 and in Ontario it is the Succession Law Reform Act.2 Different provinces have different laws regarding how closely related a person must be before he has the necessary standing to bring such an application. In British Columbia an application under the Wills Variation Act can only be brought by a spouse or child. In Ontario the class is much broader and it is to be expected that British Columbia and other provinces will extend the class in the future. There is no similar restriction on who may bring an action to set aside a will for undue influence.

(The laws governing which particular dependants’ relief legislation applies will be determined by the domicile of the testator. As to personalty, an Ontario-based charity will be subject to British Columbia’s Wills Variation Act if the testator was domiciled in British Columbia at the time of his death even if the will was written in Ontario while the testator resided in Ontario. However, under conflict-of-laws provisions in the British Columbia Wills Act,3 Ontario law will continue to apply to real estate assets located in Ontario, but not to personalty, such as bank accounts, located in Ontario.)

Charitable Remainder Trusts

For all of these reasons, it is important to consider alternatives to a testamentary gift. One of the most common alternatives is the use of a charitable remainder trust. As a trust is treated by the Canadian Income Tax Act4 as a separate legal entity, the property is owned by the trust rather than the testator at the time of his death. The property flows out of the inter vivos trust to the named beneficiaries pursuant to the terms of the trust deed. Under the common law, the trust has removed the property from the estate and therefore it is not subject to the laws governing testamentary dispositions.

Another advantage is that because the trust is an inter vivos document, the charity takes an interest immediately upon the trust being settled. If the settlor is having all of the income paid to himself or someone other than the charity, then the charity does not receive any financial benefit until the life interest is finished. In that situation, the charity’s interest is dependent upon the trust not being revoked prior to the death of the life tenant. However, if the trust is irrevocable, the charity’s interest has irrevocably vested immediately even if the benefit is not received until a later date.

Frequently the settlor is concerned that he may need the capital at a later date and therefore does not want to make the trust irrevocable. If it is a revocable charitable remainder trust, the charity’s interest is subject to termination prior to the death of the settlor/life tenant. While the settlor retains full legal power to revoke such a charitable remainder trust, he may be more hesitant to do so knowing that the trustee must be notified. If the charity is also the trustee, the settlor will have additional hesitation in revoking the trust. Thus, even a revocable trust is preferable to a bequest since in a will the revocation or change of a charitable beneficiary can take place without the knowledge of the beneficiary charity.

Revocable Charitable Remainder Trusts

The problem with revocable charitable remainder trusts is that they may not be adequate to withstand an attack under a province’s dependants’ relief legislation. Charities can be quite confident that for wills governed by British Columbia law, property held in a revocable charitable remainder trust will be adequately protected from an attack under the Wills Variation Act. The jurisdiction for probate is determined by the domicile of the testator rather than by the location of the charity. A revocable trust is also effective against an attack in a matrimonial property dispute in British Columbia under the Family Relations Act.5 A revocable charitable remainder trust may not be similarly protected in other provinces.

The most frequent use of revocable charitable remainder trusts is found in the United States. However, there are significant differences in the tax consequences of such trusts between Canada and the United States. Under the tax laws in the United States, a revocable trust is a flow-through instrument with no adverse tax consequences to a settlor when assets are settled in the trust.

In Canada, a settlor triggers capital gains upon settling property in a trust. Donors are often not willing to trigger these immediate taxes to settle a charitable remainder trust when they could be delayed by making the gift through a testamentary bequest. This reluctance may be overcome in some situations when the donor calculates the cost of realizing, and thereby “freezing”, the capital gains at today’s value as opposed to having them continue to increase until his death. He may also be able to make more effective use of any tax receipt while he is still alive rather than waiting until death when there is no possibility of carrying any excess deductions forward.

It should be noted that this concern about triggering capital gains taxes is an academic one if the settlor is dealing with assets which have not appreciated in value. If the settlor has cash or term deposits which he wants to use to settle the trust, there is no capital gains problem. There is no longer a gift tax on such a settlement anywhere in Canada. As there are no capital gains, there is also no need for a large charitable deduction at death.

Income Attribution Problems

Settlors of revocable trusts must also face an income attribution problem. This is found in subsection 75(2) of the Income Tax Act which reads:

Where, by a trust created in any manner whatever since 1934, property is held on condition

(a) that it or property substituted therefor may

(i) revert to the person from whom the property or property for which it was substituted was directly or indirectly received, or

(ii) pass to persons to be determined by him at a time subsequent to the creation of the trust, or

(b) that, during the lifetime of the person from whom the property or property for which it was substituted was directly or indirectly received, the property shall not be disposed of except with his consent or in accordance with his direction any income or loss from the property or from property substituted therefor, any taxable capital gain or allowable capital loss from the disposition of the property or of property substituted therefor or such part of any capital gain or capital loss from an indexed security investment plan as may reasonably be considered to be derived from the property or from property substituted therefor, shall, during the lifetime of such person while he is resident in Canada, be deemed to be income or a loss, as the case may be, a capital gain or capital loss, as the case may be, or a taxable capital gain or allowable capital loss, as the case may be, of such person.

Subsection 75(2) attributes any income or loss and any capital gain or loss from a revocable trust back to the settlor whether or not the settlor actually received the income or the capital gain. This means that if all of the income of a revocable charitable remainder trust is to be paid by the trust to the charity, the settlor must bring all of that income into his taxable income even though he did not receive one cent of it.

The problem is even greater because the donor cannot be issued a receipt for the “gift”. There is no “gift” from him. The “gift” is money earned in the trust which is to be paid to the charity. While it is possible to flow income out of a trust and reduce that income by expenses realized in the trust, there does not seem to be any way to flow a charitable donation receipt out of a trust to a beneficiary or settlor. A charitable receipt issued to a trust is only effective to reduce thattrust’s taxable income by 20 per cent. If all of the income flows out of the trust, the receipt is of no value whatsoever.

It should be noted that subsection 75(2) catches the settlor in three circumstances. The first is where the property and the trust may revert to the settlor. This is the standard revocable trust. The wording of subsection 75(2) very clearly catches revocable charitable remainder trusts. However, if all of the income is being paid out of the trust to the settlor, this attribution “problem” is not a negative factor at all. It is only a problem when income is paid to someone other than the settlor.

The second situation is where the settlor may determine, at a time subsequent to the creation of the trust, the persons to whom the trust property should pass . This means that if the settlor wants to create a charitable remainder trust today but reserves the right to determine which specific charities should benefit from the trust at a future date, the income is attributed back to him. The attribution provisions apply in this cirsumstance whether the trust is revocable or irrevocable.

The third situation where 75(2) applies is where the settlor gives the property on a trust and directs that as long as he is alive, the trustee must obtain his consent or his directions before disposing of the trust property. It is not an infrequent occurrence for a settlor to want this type of control when he is transferring property other than cash into a trust. It is therefore very important to keep this provision in mind to avoid adverse tax consequences. Again, this provision catches irrevocable trusts as well as revocable trusts.

It is of significance to note that it is only income from “property” which is attributed back to the settlor. Revenue Canada’s Interpretation Bulletin IT-369 makes it clear that subsection 75( 2) does not apply to business income or losses even if the business operates with some or all of the property obtained originally from the settlor. The definition of”property” as set out in subsection 248( 1) of the Income Tax Act would include cash transferred into a trust.

Interpretation Bulletin IT-369 also states that interest earned on interest accumulated in the trust is not attributed back to the settlor. However, that is of small comfort as the interest will normally be paid out to the charity and will not, therefore, accumulate in the trust. If it accumulates in the trust, then it will be taxed in the trust. If it was flowed through to the charity, it would be taxed in the hands of the charity and would therefore be exempt from taxation.

If the settlor is having all of the income from the revocable trust paid out to him, these adverse tax implications are not a problem. The income must then necessarily be taxed in his hands and he in tum can make a gift of it to a charity of his choice and obtain a receipt for tax deduction. From the charity’s perspective, this scenario has a disadvantage in that it loses control of the money and has no quarantee that the donor will return any of the income earned in the trust to that particular charity. An additional problem arises from the fact that the charity has incurred the administrative expense of creating and administering the trust and handling the investments and is not being compensated for those services.

The attribution of income and taxable capital gains only continues during the lifetime of the settlor while he is resident in Canada. If a settlor ceases to be a resident of Canada, the attribution provisions do not apply. However, while the settlor is resident, Interpretation Bulletin IT-369 makes it clear that property previously settled in the trust when the settlor was a non-resident as well as property settled while he was a resident, will be taxed. This means that if a U.S. resident sets up the trust, he has no attribution problems while he is a resident of the United States. However, if he subsequently moves to Canada, the attribution thereafter applies to property transferred to him while he was a non-resident as well as to any additional property transferred after he became a resident.

Since there is only attribution during the lifetime of the settlor, capital gains in the trust which are not realized prior to his death would not be attributed back to him. Nor would there be any attribution on deemed disposition immediately prior to death because the property was owned by the trust and not the deceased. Therefore, a revocable charitable remainder trust is useful to avoid capital gains as those gains would be flowed through to the charity upon the death of the settlor and be realized exempt from taxation in the hands of the charity.

Irrevocable Charitable Remainder Trusts

Irrevocable charitable remainder trusts do not have income attribution problems if the settlor does not reserve the right subsequently to designate the recipient charity and does not place restrictions on the disposition of the property during his lifetime. Consequently it is in the interest of both the charity and the settlor to consider using an irrevocable trust. From the charity’s point of view, this means that the settlor has made an irrevocable commitment to the designated charity of the property settled in the trust and so there is greater certainty of receiving proceeds. From the settlor’s point of view, there is the advantage of not having to worry about income attribution for money earned in the trust and paid to the charity but not received by the settlor.

There is an additional advantage: an irrevocable trust opens up the possibility of funding an inter vivos trust by will. Relying on the doctrine of”incorporation by reference”, a testator can pass all or part of his estate to the irrevocable trust. All the testator needs to do in his will is identify the trust properly by name; he does not need to set out the terms of the trust in the will. As a will becomes a public document once it is filed in the courts for probate, this funding method protects the secrecy of the testator’s charitable and other distributions.

The greatest disadvantage of an irrevocable trust to the donor is that he no longer has the option of regaining title to the property should it be required by him due to a reversal in his own financial fortunes. That is the element of the revocable charitable remainder trust which is most important to the settlor who is concerned about his own long-term welfare and security. This particular problem can be addressed by loaning money to an irrevocable trust. The trust itself is irrevocable, but it may only have a vested capital of$100. The remaining money is simply loaned to the trust and can be recalled, therefore it attains the most important feature of a revocable trust. This will be dealt with more explicitly later in this paper.

Tax Concerns in Irrevocable Trusts

One of the most common formulas for charitable remainder trust agreements is as follows: the settlor is made an income beneficiary of all, or a stated portion, of the trust’s income and the charity is made a residual beneficiary of the capital. Provision is then made in the trust for the income beneficiary to waive his right to income in favour of the charity.Ifthe settlor receives all of the income due to him under the irrevocable trust, the income is taxed in his hands and he is free to use it for his own use or give it back to the charity. If he gives it to a charity he can obtain an income tax receipt.

A tax problem arises if he chooses to waive his income interest in favour of the charity. The irrevocable trust gives the income beneficiary an income interest in the trust. An assignment or renunciation of an income interest in a trust results in the fair market value of that income interest being included in the income beneficiary’s taxable income.

In considering the tax implications of a renunciation of an income interest in favour of a charity it is necessary to pay attention to subsections 69( 1) and 56(2). Subsection 69( 1), which is not relevant to cash gifts, reads:

Except as expressly otherwise provided in this Act,

(a) where a taxpayer has acquired anything from a person with whom he was not dealing at arm’s length at an amount in excess of the fair market value thereof at the time he so acquired it, he shall be deemed to have acquired it at that fair market value;

(b) where a taxpayer has disposed of anything

(i) to a person with whom he was not dealing at arm’s length for no proceeds or for proceeds less than the fair market value thereof at the time he so disposed of it, or

(ii) to any person by way of gift inter vivos,

he shall be deemed to have received proceeds of disposition therefor equal to that fair market value; and

(c) where a taxpayer has acquired property by way of gift, bequest or inheritance, he shall be deemed to have acquired the property at its fair market value at the time he so acquired it.

Subsection 56(2)reads:

A payment or transfer of property made pursuant to the direction of, or with the concurrence of, a taxpayer to some other person for the benefit of the taxpayer or as a benefit that the taxpayer desired to have conferred on theother person shall be included in computing the taxpayer’s income to the extent that it would be if the payment of transfer had been made to him.

Interpretation Bulletin IT-385R makes it clear that Revenue Canada takes the position that an assignment of an income interest in a trust from the income beneficiary to the charity which is a residual beneficiary would be a gift as contemplated by subparagraph 69( 1)(b)( ii) and that there are deemed proceeds to the income beneficiary equal to the fair market value of the income interest. The same proceeds of disposition are deemed to result ifthe income beneficiary formally renounces his interest or simply abandons it without consideration in favour of the charity.

Since the trust is irrevocable, the settlor cannot simply revoke the trust and start with new terms and conditions when he decides that he wants to reduce the amount of income which he receives. The settlor/income beneficiary will have difficulty understanding that Revenue Canada will tax him for his generosity in waiving his income interest in favour of a charity. If he renounces his interest once and for all, he will not only be taxed on his income for the year in which he renounced but the value of his income interest over his normal life expectancy will be calculated and that total amount included in his income in the year in which he renounces. This is a very onerous financial penalty to pay for a charitable gift. There would not even be a donation tax receipt to offset the deemed income to the income beneficiary.

These problems only present themselves ifthe settlor wants to waive any future income right in favour of the charity. If he intends to receive all the income and then give it to the charity or use it for his own purposes, there are no problems under Interpretation Bulletin IT-385R which need to concern him. However the charity will want to avoid using a planned giving instrument in such a way that it precludes the possibility of the settlor having a more generous attitude in the future.

Charitable Loans

The solution lies in having all the income paid to the charity but using loans to fund the irrevocable trust. Not only will the loan give it the element of being revocable because the benefactor can recall his loan, it also allows him to set the income return that he requires from the trust. He can waive his income from a loan without attracting the adverse tax consequences set out in Interpretation Bulletin IT-385R for waiving income from a trust.

If the benefactor loans $10,000 to the trust, he can set the terms under which he can recall the capital in the promissory note. If he requires a 10 per cent return on his money, he can have the promissory note stipulate that the trust pay 10 per cent as the borrowing cost for obtaining the money. If the benefactor chooses to waive the interest due to him, he can do so without any adverse tax implications. If he wants to receive only a five per cent return on his money, he can set that in the terms of his loan. The balance will be income to the trust and will be paid to the charity on a tax-free basis.

Tax-Planned “Gifting”

This raises the question: when is it best for the donor to receive money in his own hands and give it to the charity as opposed to permitting the income to be earned in the hands of the charity? The answer to this question depends upon how much income the donor has and how much other charitable giving he does. An interest-free loan to a charity will usually yield a better net result than having a donor earn the income in his own hands and give it to the charity.

A donor is only allowed to deduct 20 per cent of his taxable income for charitable gifts. If a charity pays a benefactor $1,000 interest on a $10,000 loan, that $1,000 must be brought into the benefactor’s taxable income. If the benefactor then gives the entire $1,000 to the charity, he would receive a $1,000 income tax receipt. The donor would need to have $4,000 additional taxable income before he could benefit from the entire receipt. If the donor has $5,000 taxable income and gives the entire $1,000 to the charity he is in substantially the same financial position as if he had never received the income in the first place.

The charity is also in substantially the same financial position. If the charity had earned the money in its own name, it could keep the entire $1,000 because it does not have to pay any tax on its earned income. The disadvantage to the charity in receiving the $1,000 as a gift rather than as earned income is that it has now issued a receipt for $1,000 and therefore it must include that $1,000 in its disbursement quota calculation. A “charitable organization” would have been able to retain the entire $1,000 in its endowment or administrative funds if it had not issued a receipt. (If the charity is a “charitable foundation” as opposed to a “charitable organization”, it will have to distribute a 4.5 per cent return on its capital which is $450 on the $10,000 loaned.)

If the donor does not have any other income, he will be in a substantially worse position by virtue of having exchanged cheques with the charity instead of having made an interest-free loan to the charity. He would only be able to use a $200 deduction in that year even with the $1,000 receipt. He would have to bring the remaining $800 into his net taxable income. If his marginal rate were 50 per cent, he would have to pay $400 tax and consequently would have to find $400 after-tax dollars to meet this tax liability.

The only situation in which a donor has a tax advantage if he receives income from the charity is where the donor has not used his $1,000 interest-anddividend income deduction under subsection 110.1( 1) and is already using his maximum 20 per cent charitable deduction allowance. In that situation, the $1,000 deduction will be used to calculate his taxable income before the 20 per cent is calculated. Therefore the net reduction in taxable income is only $800 because the donor cannot deduct 20 per cent of the $1,000 interest-earned deduction.

Forgiveness of Loan

The problem with using a loan to give an irrevocable trust the flexibility of a revocable trust and to avoid the adverse income tax consequences of attribution and waiving an income right is that, on the death of the person making the loan, the principal of the loan remains an asset of his estate. The whole point of introducing trust agreements was to move assets out of the testator’s estate while he was still alive so that there would be no concern about the gift being challenged under any relevant dependants’ relief legislation. The “Great Circle Route” has brought us back to an original problem. The challenge is to structure the terms of the loan and promissory note in such a way that it passes to the charity after the death of the settlor without becoming a testamentary disposition.

Many people attempt to deal with this problem simply by having a loan forgiven upon the death of the testator. The difficulty is that simple forgiveness on death is almost certainly a form of testamentary disposition.If the document does not comply with the formal execution requirements of the Wills Act,the disposition will fail. If it is executed in such a way that it stands as a valid testamentary disposition, it will have to come into the estate and be probated and therefore be vulnerable to attack under dependants’ relieflegislation. There is also a significant possibility that any subsequent will will revoke the forgiveness because the opening recital of a will almost always revokes “all previous wills or testamentary dispositions of any kind”.

The High Court of Australia discussed what factors determine whether a document is a testamentary disposition or a valid deed in Bird v. Perpetual Executors.6 The conclusion was that the guiding principle is that if the forgiveness provision is immediately and irrevocably binding upon the grantor as an executed covenant, then it is no objection that the covenantor’s death is the event upon which the obligation is to be fulfilled. A covenant is binding provided that it is signed, sealed and delivered.

If the deed or instrument is constructed so as to be merely a direction to the executor to pay the debt out of an estate, or to forgive the debt of the estate, then it will be a testamentary disposition. Moreover, a benefactor will usually require the option to recall the loan during his lifetime and so the forgiveness is not irrevocably binding upon him. Consequently, it is a testamentary disposition to forgive a loan upon death if the benefactor has the right to revoke the foregiveness provision during his life.

The Ontario Court of Appeal in Carson v. Wilson 7 dealt with a situation where a grantor signed a deed transferring land to grantees which would have been immediately binding on the grantor if delivered and registered. He did not deliver the deed to the grantee but left it in the custody of his solicitor with instructions that it be delivered to the grantee at the time of his death but not before. Because he retained the right to recall the deed prior to his death and delivery was contingent on death, the Ontario Court of Appeal held that the document was a testamentary disposition. The deed (and therefore the transfer)failed because the deed did not meet the execution requirements under the Wills

Act.

The solution is to create a condition in the loan which is immediately and irrevocably binding on the grantor and which he can fulfill during his lifetime but which becomes impossible to fulfill after his death. The promissory note could contain a clause which stipulates that the loan is only payable 30 days after the debtor receives a written demand signed and dated by the grantor’s own hand in front of a witness. It could also contain an immediately and irrevocably binding “deemed forgiveness” provision upon it being established that the grantor is unable to fulfill the conditions necessary for payment of the loan.

It would appear simpler to dispense with the irrevocable trust and simply loan the money to the charity under the terms of a deposit agreement with the forgiveness covenant set out above. The risk involved in that procedure is that Canadian courts have not ruled whether such a clause accomplishes the result sought and that question does not change if the loan is forgiven in favour of a trust or is forgiven to the charity directly. Until Canadian courts have ruled on the effectiveness of such wording, it would be prudent to have the testator forgive any outstanding loans in his will in addition to such a covenant in the promissory note.

Interpretation Bulletin IT-226

Interpretation Bulletin IT-226 deals with a gift of a residual interest to a charity.

The gifts must vest at the time of the giving and the life tenant must have no right of encroachment on capital if a deduction is to be granted. The value of the residual interest is determined by deducting the value of any life interest from the total value of the interest.

If the settlor chose not to reserve any income to himself and irrevocably assigned all the income as well as the residual capital to the charity, he could argue that he was entitled to a receipt for the entire amount of the capital transfer. As the charity would be entitled to all the income as well as the capital, it would meet the required conditions under Saunders v. Vautier8 which compel the trustee to transfer the capital immediately to the charity. However, the Supreme Court of Canada has held in Halifax Schoolfor the Blind v. Chapman et a/ 9 that the general rule in Saunders v. Vautier does not apply to perpetual charitable trusts so the careful draftsman may still want to cover off the potential for such a claim on the corpus of the trust fund in the trust deed itself.

Interpretation Bulletin IT-226 does not mention a trust but it would seem that a trust would necessarily be required for a life interest in anything other than real property. Legal interests in realty or personalty are not covered in the Income Tax Act. In those circumstances, given the uncertainty as to whether there can be a legal interest in personal property, it is certainly wiser to use a trust instrument.

The Income Tax Appeal Board case Mitchell v. Minister of National Reve-

nue10stands for the proposition that a gift to a trust is a gift to the beneficiary of the trust. Revenue Canada must accept this principle as it is a necessary presupposition for Interpretation Bulletin IT-226 to be a correct interpretation of the law. Paragraph 110(1)(a)(i) of the Income Tax Act only authorizes deductions for donations to “registered charities”. An irrevocable charitable remainder trust is not a “registered charity” within the definition in the Income Tax Act, but it is the type of trust which is necessary for a gift of a “residual interest” to a “registered charity”.

Annuities One of the planned giving instruments which interests charities the most is the charitable gift annuity. This is a contract between the charity and the annuitant under which the charity pays the annuitant a fixed amount every month for as long as the annuitant is alive. The necessary amount of capital is calculated using the actuarial tables set out in Interpretation Bulletin IT-111R.

The fact that Revenue Canada has issued an Interpretation Bulletin detailing how “charitable organizations” should compute annuity contracts is not legal authority for charities to engage in such contracts. There is significant doubt as to whether a charity has the legal authority to enter into such contracts given the regulatory restrictions which the Superintendent of Insurance places on such business. Another issue arises should a charity succeed in achieving a considerable volume of annuity contracts. Would it then be held that the charity is carrying on a “business” which might result in its deregistration as a “registered charity”?

Because of these uncertainties it is my practice to counsel charities against issuing their own annuity contracts. My principal concern is that charities seldom have the necessary expertise and volume of contracts to permit them to calculate appropriate reserves and returns. If the annuitant outlives the actuarial projection or revenues from investments fall, the charity would have to dig into opertional revenues to fund the annuity payments yet it is doubtful whether a charity has the lawful authority to use its charitable resources to make annuity payments to individuals. Without skilled professional management, charitable annuity contracts can lose, rather than make, money and expose the charity and its directors to legal liability.

Irrevocable Charitable Annuity Trust

If there is a large amount of capital and the potential benefactor is elderly, an alternative to an annuity contract would be the setting up of an irrevocable charitable annuity trust. This trust would distribute a fixed amount of capital to the annuitant each month for as long as the annuitant lived . If the trust were properly constructed, the annuitant would be receiving a distribution of capital from a trust and therefore would receive his monthly payments tax free. If he chose to waive his right to a capital distribution in any month or for a period of time, there would be no adverse tax consequences like those which would result if he waived his right to an income interest in a trust. Upon the annuitant’s death, all of the remaining capital would go to the charity.

As the capital is held in a separate trust, the annuitant does not need to worry about the funds being co-mingled with the charity’s assets and thus subject to an attack by the charity’s creditors. It would be a term of such an irrevocable charitable annuity trust that all of the income would be paid to the charity. The income would be flowed out of the trust to the charity and therefore would be exempt from taxation. The annuitant would have the satisfaction of knowing that the charity was receiving an immediate benefit and that his capital was earning income without taxes having to be paid. The charity would not only receive a benefit prior to the annuitant’s death, it would have no liability if the annuitant outlived the actuarial projections.

The problem with this instrument arises when the annuitant lives longer than the calculated number of monthly capital distributions. The significance of this problem will depend on whether the annuitant has other assets for his security. The solution is to purchase a deferred annuity contract as insurance to guarantee the payment of the same level of monthly distribution after the capital in the trust has been exhausted. Since it is a deferred annuity, the payments will not begin until the date that the trust is scheduled to be exhausted and only then if the annuitant is still alive. The impact of Section 12.2 of the Income Tax Act which states that accrued interest must be included in income must be considered when deciding whether the deferred annuity contract should be owned by the charity, the trust, or the annuitant.

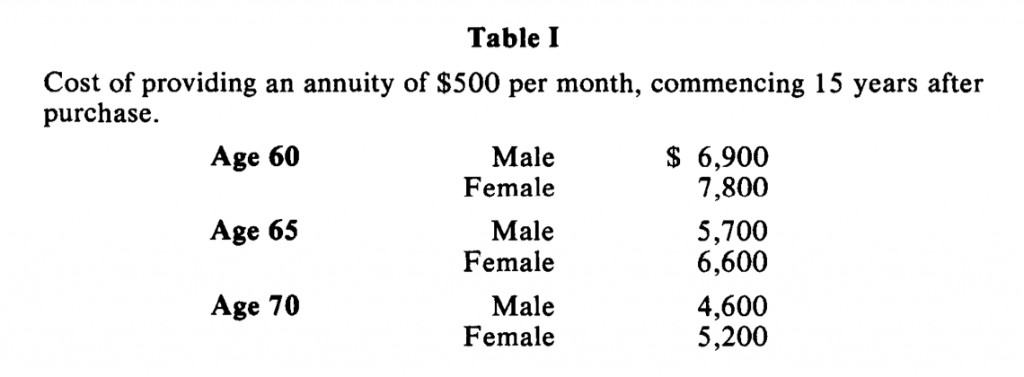

If the annuitant is 70 years old in 1985 and requires $500 a month, a $90,000 contribution to an irrevocable charitable annuity trust would guarantee tax-free monthly payments of$500 until the year 2000 when the annuitant reached the age of 85. A deferred annuity contract guaranteeing $500 monthly payments to a male annuitant beginning in the year 2000, would have cost just $4,600 in May, 1985. The charity will receive substantially more than that as income from the trust in the first year. Given the income which the charity will earn in those 15 years and the potential acquisition of the capital remaining at a death prior to the year 2000, the deferred annuity insurance premium is a reasonable cost for the charity to incur for continuing the payments after that date if necessary. Table I shows calculations illustrating the costs and benefits of this type of planned giving instrument.

(Note: the above figures are based on long-term interest rates in the range of 11 per cent. Given recent declines, it may be prudent to assume 10 per cent as a more conservative estimate. This will result in a cost increase of approximately 20 per cent-annuities with long deferred periods are particularly sensitive to interest rate fluctuations.)

In addition to the positive income benefits, this proposal also guarantees that the charity will have no open-ended exposure to a future financial liability to the annuitant. It also benefits the annuitant because he is assured that he will never become a financial liability to a charity which he was hoping to benefit. More importantly, he is more secure financially because he need not worry about the financial viability of that particular charity 15 years in the future.

There are other possible solutions to the problem of the annuitant outliving the projections on the actuarial tables. One modification would be only to pay out the income to the charity for a fixed period of years. After that time, income would accumulate in the trust to increase its asset base. Another possibility is to instruct the trustees to invest in very safe equity growth securities. The trust would then not be receiving income which would be taxed in its hands nor would it be distributing income. If the settlor lived for too long a period it would be necessary to liquidate the appreciated assets, pay the taxes and continue the capital distributions to him. However, ifhe were to die before it was necessary to use all the capital, the appreciated assets could flow through the trust to the charity and be disposed of by the charity on a tax-exempt basis.

There is one potential problem with the irrevocable charitable annuity trust. Subsection 75(2) provides for income attribution if the capital of a trust “reverts” to the settlor. Such a trust must therefore be very carefully constructed so that the monthly capital payments are an explicitly directed payment of a capital to a named beneficiary and not capital reverting to the settlor in installments. Properly constructed, an irrevocable charitable annuity trust clearly falls outside the definition of a “reversion” as interpreted by the courts. It is less clear that it falls outside the definition of”revert”. I am unaware of any case authority deciding the meaning of”revert” as used in the Income Tax Act. The challenge is to construct the instrument so that when an “orange” goes in, what comes out is not a “piece of orange” but an “apple”.

Insurance

Just as I am hesitant to promote conventional or charitable annuity contracts as planned giving instruments, so I am less enthusiastic than some about the potential of insurance programs for this purpose. Conventional insurance programs frequently appear to benefit the insurance industry more than the charity.

Not enough consideration has been given to the technical and legal considerations which a charity should bring to its structuring of an insurance program. The principal thrust has been the marketing emphasis provided by the insurance industry. If the charity’s constituents begin reducing their operational giving because they are contributing monthly to insurance premiums in favour of the charity, there is also a significant potential for such a program actually to reduce revenues rather than increase them.

It is not my intention to canvass extensively the technical, tax and legal considerations which should be addressed when a charity designs a planned giving program based on insurance. However, I do want to point out a couple of situations where insurance combined with other planned giving instruments can provide a very beneficial result. The first involves a loan and the second involves annuities in a situation where it is anticipated that the estate may be subject to an attack under dependants’ relief legislation.

Insuring Loans

Situation 1:

A benefactor with a reasonably high income is prepared to make an interest-free

loan to a charity. He is further willing to agree that it need not be repaid until his death. However he must insist on being repaid at death either because he needs the cash to pay his capital gains taxes or because he wants to pass the money on to his family.

In this situation the charity could obtain a fully paid up insurance policy on the benefactor’s life for the principal value of the loan. Having obtained that policy and assigning it specifically to the repayment of that loan, the charity can then prudently spend the capital of the loan because its repayment is guaranteed. Now that the benefactor has a documented guarantee that the loan will be repaid, he could use that as collateral at a financial institution to borrow money should it be required by him due to a financial reversal.

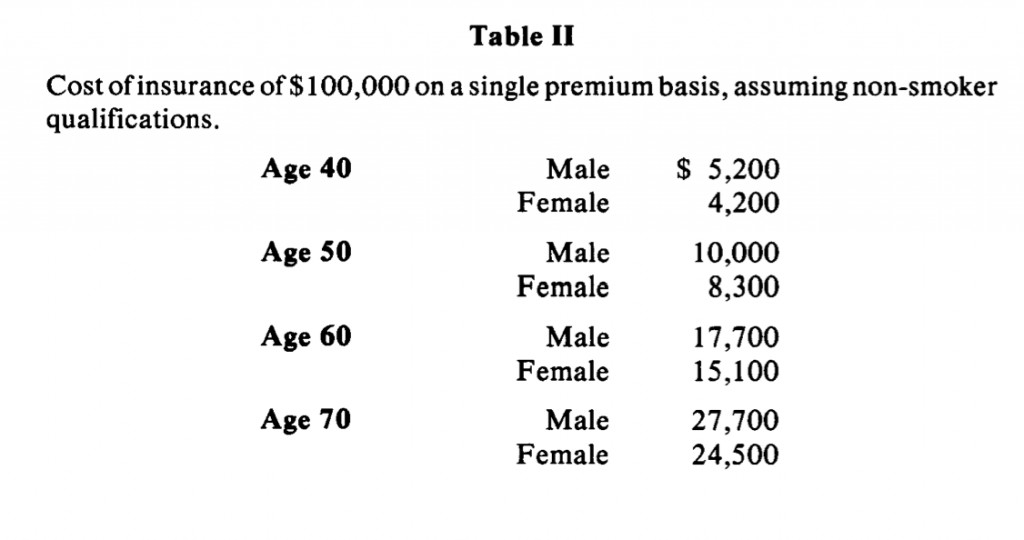

This scenario allows the charity to spend the capital today without worrying about any financial reversals which it might face. It also reduces its moral obligation to the benefactor should the benefactor suffer a future reversal of fortunes. Table II sets out the single premium costs of such insurance on a $100,000 loan.

Annuity-Funded Insurance

Situation 2:

Insurance can also be a useful instrument for passing money to a charity without its being an asset of the estate. In a situation where an individual with a significant amount of capital is concerned that greedy relatives or an unhappy spouse may seek to obtain his assets upon his death, consideration should be given to purchase of a very high income-yielding annuity contract. The annuity provides security to the person for as long as he is alive but will leave no assets in his estate and if the annuity contract has no fixed term certain, the annuitant will be able to obtain a higher income yield during his lifetime. Such a contract guarantees both his security while he is alive and that no interest will remain in his estate after he is gone.

Ifthe annuitant wants to leave capital for certain individuals or charities, and he is able to obtain life insurance, he can take out a life insurance policy and have it paid to a named beneficiary. He can then pay the premiums out of his monthly annuity payment. That payment will not cease until his death so he need not worry about funding for future payments.

In British Columbia the annuitant could own the life insurance policy and know that it would go to the designated beneficiary without being challenged under the Wills Variation Act. In Ontario steps should be taken to ensure that the annuitant does not own the policy or it will be caught by the Succession Law Reform Act. Of course, if the benefactor donates the premiums to a charity and the charity is the irrevocable owner of the insurance contract, then the proceeds would be free from attack in Ontario as well as in British Columbia.

This scenario becomes even more attractive if the benefactor holds a significant amount of money in RRSPs which he must liquidate when he reaches 71. He can roll his funds tax free out of an RRSP into an annuity and delay the taxes until he receives each annuity payment. If he purchases a life annuity with no guarantee, he will get a maximum income return and there will be no taxable proceeds from his RRSP falling into his estate. Instead he will receive tax free proceeds under the insurance contract.

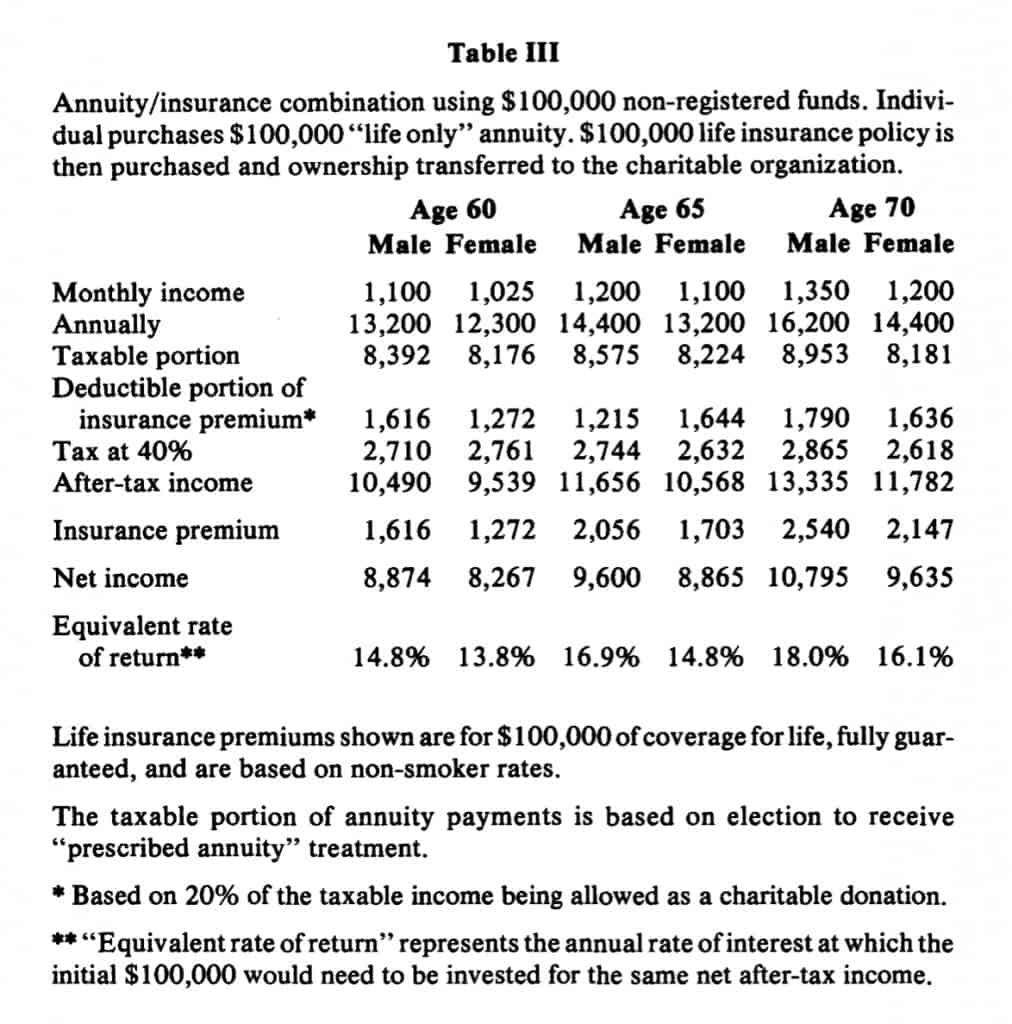

Table III sets out a calculation of the after-tax benefit of this type of planning when the annuity is not funded with RRSP dollars. For this scenario to be applicable, the benefactor must be insurable. It is preferable for the annuity and the insurance policy to be issued by separate companies. In certain circumstances, there is an additional advantage if the annuity is an irrevocable charitable annuity trust or a variation of the same rather than a normal annuity contract.

Complications Arising From Use of a Trust

Using trusts in planned giving instruments introduces some technical complications. The first is that the trust is treated by the Income Tax Act as a separate legal entity and consequently has an obligation to file a T3 income tax return. This requirement remains even if all of the income in any year is flowed out of the trust either to the settlor or to the charity. An inter vivos trust has a fiscal year end of December 31 of each year. The Income Tax Act dictates that date and an inter vivos trust does not have the flexibility in choosing a fiscal period that a corporation or a testamentary trust have.

It should also be remembered that a trust has a deemed disposition of all of its assets every 21 years. If the trust holds capital assets which are appreciating, that deemed disposition can trigger substantial capital taxes and it may be necessary to dispose of certain assets to pay those taxes. An alternative is to distribute the capital prior to the 21 years. The capital could be received by a charity without triggering tax. This alternative may not be prudent for a settlor who is relying on the income of the trust to provide for him for the rest of his life.

Protection From Creditors

The principal disadvantage to the benefactor of simply depositing a loan with the charity is that he would have no special protection from, or priority over, the other creditors of the charity. If the money is loaned to a trust, those funds are segregated from the general assets of the charity . Creditors cannot attack or attach trust funds held by the charity even though they may receive the income from those trust funds. It is only when the income is paid to the charity that the creditors can have an opportunity to benefit. If the money is simply loaned to the charity, a creditor who brings execution proceedings can seize any assets of the charity or funds held in its name. The charity could only repay the benefactor if it had additional funds or assets.

Choosing A Trustee

It is very important to choose a corporate trustee for charitable remainder trusts. A charity is in a position to serve its own interests at the expense of the income beneficiary when it is both the trustee and the residual beneficiary. Conversely, by the principles of equity set out by the Court of Appeal in England in Re Hallett’s Estate 11 a trustee is forever liable for what he distributes to himself. The charity is given much more protection if it is not its own trustee.

It is not clear that a charity has the legal capacity to carry on a trust business. The answer to that question will vary from province to province. The conservative answer is that only licensed trust companies should be in the business of acting as trustees. A trust company also has full legal authority to carry on the “banking” business of accepting deposits and loans and paying out interest.

A trust company not only provides independence and freedom from conflict of interest, it provides professional management and an image of competence and professionalism. The corporate trustee will charge fees for the services of administering the trust and managing the investment. These are services which are legitimately charged to the income beneficiary. Employing a corporate trustee enables the charity to pass those costs on, whereas a charity acting as its own trustee must absorb them. Not only is that expensive, it is possibly not an appropriate use of charitable funds.

More Problems

This paper will not attempt to deal with the legal and tax considerations which arise in drafting the various types of trust agreements in a planned giving program. Income attribution and the tax costs of waiving an income right are issues of primary concern to the donor. The charity’s primary concerns are investment powers and restrictions and the application of the even-handed rule, authority to pool and co-mingle funds, and compliance with tax and corporate laws governing trusts. Nor will this paper address the corporate structure issues which a charity must consider when the legal infrastructure for its planned giving programs is determined. This paper has raised enough problems without addressing those issues.

However, consideration must be given to the corporation’s objects and the potential for directors’ liability for ultra vires activities. Charities should also understand the different disbursement quotas and authorized activities for “charitable organizations” and “charitable foundations”. These are important considerations when a charity is deciding whether a planned giving program should use a parallel foundation as its primary fund-raising vehicle or to hold endowments.

The recent Ontario High Court of Justice decision in Re Baker11 stands as a sober warning of the difficulties of trying to move charitable funds between related but separate legal entities. In that case the testator left a significant amount of money to a general hospital, subject to his wife’s life interest. The hospital subsequently set up a parallel foundation and a research centre named after the testator.The trustee of the testamentary trust wanted it varied so that the bequest could be paid to the foundation or the research centre rather than the general hospital. The Public Trustee opposed the motion.

The court held that it did not have the power under the rule in Saunders v. Vautier or under the cy pres doctrine or under the inherent jurisdiction of the court to approve the variation. It was not sufficient justification to pay the money to the parallel foundation simply because it was more expedient. The court went farther to say that should the hospital, after receiving the proceeds from the estate, seek to divert the proceeds from the estate to the foundation or centre, the court would intervene to restrain such conduct as being ultra vires.

Keep It Simple Stupid

Having dwelt on the complications and problems of planned giving instruments, let me conclude by proposing a simple and workable planned giving instrument.

A charity should use a trust company licensed throughout Canada as the trustee of an irrevocable charitable trust which pays to the charity on December 28 of each year all the income and all the assets of the trust fund in excess of $100 which are not required to meet the liabilities of the trust fund. (For reasons relating to the jurisdiction of Ontario’s Public Trustee under the Charities Accounting Act 13, it is better for Ontario charities to use an office of such a trust company which is outside of Ontario as the trustee so that the trust is not resident in Ontario.)

Donors should be invited to loan funds to the trust company as trustee at as low an interest rate as they can afford. The development officer then acts as the agent of the trust company to obtain such funds from donors and the trust company will transfer the funds from any local branch to the particular branch where the trust is set up. The trust company invests the money, pays the stipulated interest on the loan and any profit (after expenses) is paid to the charity. The charity benefits because it no longer needs to be concerned about security or investment competence. Also it no longer has to do the actual bookkeeping, mail the cheques or comply with income tax requirements and it now need have no concern about its legal authority to carry on a trust business or accept deposits. It is simply an active solicitor of potential depositors and a passive recipient of the net proceeds.

Donors benefit because they are free from income attribution and other problems related to trusts. The deposit agreement can, but need not, include the deemed forgiveness covenant discussed earlier. Costs are reduced because there is only one master trust agreement with many simple deposit agreements relating to it rather than a separate trust agreement with each donor.

Such a scheme can avoid additional problems which have not been raised in this paper. The changes in the definition of”charitable organization” and “private foundation” in the Income Tax Act as amended on December 20, 1984 state that a charity will be a “private foundation” rather than a “charitable organization” if more than 50 per cent of its capital has been”contributed or otherwise paid”by related persons. It is the stated intention of the Department ofFinance that such wording should cover loans to a charity as well as gifts.When the loans are being made to a separate trust, the “50 per cent capitalization rule” is no longer of even academic concern. Of greater significance, if the charity is a charitable “foundation” rather than a charitable organization, is freedom from concern about the impact which loans would have on the new disbursement quota for foundations ( 4.5 per cent of investment assets).

The greatest attraction is that although this proposal is designed to avoid the complex problems arising from revocable and irrevocable trusts and loan agreements, it requires only a simple one-page deposit agreement. The depositor has only to fill in his name, set the desired rate of interest and elect whether or not he wants the “deemed forgiveness” clause. Very little documentation is required and it is a concept that is even easier for donors to understand than the concept of the revocable charitable remainder trust.

Conclusion

Charities and their development officers must have a comprehensive understanding of the technical tax and legal considerations in different planned giving instruments if they are to begin to tap financial resources which require more effort than simple solicitation of a donation. Simple planned giving instruments such as trust deposit agreements are nice, but the limitations of any vehicle designed for the broadest possible application become apparent when anything more than a simple gift is contemplated, e.g., the wealthy farmer who wants to leave a quarter section of land to charity or the businessman who wants a charity to benefit from 10 per cent of the equity growth in his company. Their charitable intent is seldom realized because the frustration they feel as they try to obtain competent and creative technical advice overcomes their resolve to give.

Canadians will need to develop and design planned giving instruments which reflect Canadian tax and estate laws rather than trying to copy what their American counterparts use. For example, it is my opinion that both the trust deposit agreement and the irrevocable charitable annuity trust proposed in this paper are superior to the revocable charitable remainder trust and charitable gift annuity for Canadians. These instruments will not have universal application or be acceptable to all donors but when they are used appropriately they offer a better net return to the charity. If the donor requires a significantly higher return, then the charity must ask itself seriously whether it can, or should, be dealing with that particular donor.Planned giving instruments should only be used when they expose the charity to a minimum of financial risk and have a significant potential for providing financial benefit.

When the potential of “The Great Circle Route” to produce planned gifts through instruments other than wills is recognized, the cost-benefit analysis of a planned giving program will be much more favourable. The initial marketing emphasis can be on wills because that is what is understood best by most donors. Then the appropriate planned giving instrument can be introduced as the donor’s estate is analyzed and his charitable intentions are understood. With a comprehensive understanding of the tax and estate considerations, the development officer can propose the instrument which will best serve the interests of both the donor and the charity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author wishes to thank Professor Donovan Waters of the Faculty of Law of the University of Victoria for his helpful comments and criticisms of this paper in its draft stage.

FOOTNOTES

1. R.S.B.C. 1979, c. 435.

2. R.S.O. 1980, c. 488.

3. R.S.B.C. 1979, c. 434.

4. S.C. 1970-71-72, c. 63 and amendments thereto.

5. R.S.B.C. 1979, c. 121.

6. (1946), 73 C.L.R. 140.

7. (1961), 26 D.L.R. (2d) 307.

8. ( 1841), 4 Beau 115 affmd. Cr. and Ph. 240, 241 E.R. 482.

9. (1937), 3 D.L.R. 9.

10. 56 DTC 521.

11. (1894), 13 Ch.D. 697.

12. 11 D.L.R. (4th) 430. Editor’s Note: For a discussion of Re Baker see”Recent Tax Developments”, The Philanthropist

, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 57-58.

13. R.S.O. 1980, c. 65 as amended by S.O. 1982, c. 11 and S.O. 1983, c. 61.

E. BLAKE BROMLEY

Member, The British Columbia Bar