What we anticipate seldom occurs, what we least expect generally happens —Disraeli

The future for Canadian voluntary agencies in the first half of the twentieth century was assumed, and proved, to be very much like the past. Most voluntary agencies continued to be supported by private donations. Small operating budgets and staffs were augmented by volunteer help, particularly during the annual fundraising period. Voluntary agencies, like the communities they served, were comparatively stable and planning activities were confined to operating issues such as the need to provide sufficient seats in the meeting hall.

The world changed and voluntary agencies changed with it Card indices in shoe boxes gave way to computerized volunteer and donor lists; hand-painted notice board announcements were replaced by glossy multi-media advertising campaigns; infrequent night-time basement meetings became regular boardroom lunches; many agencies hired full-time paid executive directors and staff.

Whatever the benefits of the new technology and impressive offices and paid staff, it appears that an era is coming to an end and the future will once again have very little resemblance to the past. In this new era we see reduced government funding, accelerating demands for services, an increasingly disheartened volunteer base, and, recently, a sense that agencies have lost control of their destinies. Yet, in the face of this apparently bleak future, many agencies focus their planning activities on the same day-to-day operating concerns that preoccupied them in the past.

In other sectors of society, organizations are adapting to the same instability and discontinuity facing the voluntary agencies. Strategic planning is a powerful process which is helping corporations to understand and plan for their future in a rapidly changing operating environment. Governments also use strategic planning to create a rational framework for their approach to the future. Increasingly, voluntary agencies will have to adapt the strategic planning process to fit their own needs to understand and plan for the future.

Adapting the Process

Voluntary agencies have unique characteristics which require an adaptation of the strategic planning process and which hinder a direct transfer of the private sector approach and terminology. The principal constraint may well be the “voluntary” aspect itself: people with a few hours a month to devote to a particular cause may not have the time or the inclination to pursue rigourous planning. Voluntary agencies deliver services for which there are no real or perceived substitutes. Too often, performance and the effectiveness of service are not measured. Most voluntary agencies depend on funding from private, community or government sources and therefore lack the ability to generate funds internally. The focus of volunteers, staff and board members is usually short term, i.e., meeting the annual fund-raising goal or serving immediate community needs. In all of these characteristics, voluntary agencies differ from the private sector.

Nevertheless, strategic planning can be modified to allow for these factors in a way which provides a process requiring a minimum amount of paper work; which coordinates the efforts of board members, volunteers and staff; which generates a sense of participation and “ownership”; and which provides measurement which can lead to improved performance. A strategic plan will promote understanding within the organization; permit development of specific action plans to revitalize the group; indicate the need to recruit or replace volunteers; help to ensure a continuity of funding; and, most importantly, generate a consensus regarding future directions for the agency.

This article outlines the traditional strategic planning process which may be modified to suit the unique characteristics of your agency. It will prepare you to launch your own planning exercise, to set up a strategic framework suitable for your agency and to take whatever corrective action is necessary to meet the uncertainties of the future. It should also be pointed out that strategic planning may not be the answer for all voluntary agencies’ problems.1

A Classic Case: The National Foundation

The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis was an American voluntary agency founded in 1938 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, himself an adult victim of polio, to raise funds to fight the disease. Using funds primarily raised by the NFIP, medical researchers developed both the Salk and the Sabin vaccines which virtually eliminated “infantile paralysis”. This organizational successachieving its goal-proved to be an organizational disaster. The NFIP had eliminated its own reason for being.

Nevertheless, following a strategic planning exercise, the NFIP decided to continue. Realizing that its greatest strengths were in organization and fund raising, not in disease-specific research, the NFIP changed its name to the National Foundation, identified new market areas for its services, and continues to raise money today for health and other causes related to human wellbeing.

The lesson is spelled out by Philip Kotler in his book on marketing for non-profit organizations:

The organization that sticks to its historical business may find itself serving a declining market. Organizational survival is not just a matter of being efficient … but of being adaptive, that is, managing to do the appropriate things in the changing environment … An adaptive organization is one that operates systems for monitoring and interpreting important environmental changes and shows a readiness to revise its mission, objectives, strategies, organization, and systems to be maximally aligned with its opportunities.2

The components of a strategic plan which will lead to a voluntary organization’s becoming such an “adaptive organization” are: environmental awareness; realistic appraisal of strengths and weaknesses; a refined sense of critical issues and key factors for success now and in the future; and a framework within which to take corrective actions to contain threats and capitalize on opportunities.

What Is Strategic Planning?

Strategic planning is a framework and schedule of activities and meetings designed to answer these questions: what does the agency want to be and do in the future? where is it today? where does it want to go? how does it get there from here? A proper strategy allows you to establish goals and objectives for the organization, to choose among various courses of action, and to allocate the resources necessary to achieve your goals.

Strategic planning is not a quick fix for all the problems facing your organization. It is not a panacea for troubles brought about by poor management or declining demand for your agency’s services. It is not a guarantee that unforeseen events will not be detrimental to the organization.

In summary, developing a successful strategy requires an agency to make choices of sometimes conflicting missions, goals and objectives;3 to pursue a plan of action and to allocate resources accordingly; and to establish a planning framework within which the strategy can be implemented, monitored and controlled as the organization changes. A sound planning process will consist of sequential steps in several phases. It must involve the key decision makers at all levels and must result in changed behaviour-new ways of doing things-that are appropriate for the new strategy. Strategy makers must possess the authority to redistribute power, emphasize certain organizational values, change structure and take any other steps necessary to produce the changed behaviour that will lead to success.

Phases of Planning

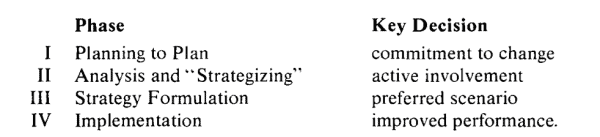

Opinions differ regarding the number of phases in the planning process. My firm uses a four-phase approach (Figure 1); others use three, six, or even seven.4

Whatever the number of phases, the concept is always the same: planning must be done sequentially in distinct phases and each phase must be as complete as possible before the next is started or the result will be flawed. In our four-phase planning model the phases are: planning to plan; analysis and “strategizing”;5 strategy formulation; implementation. Within each phase there is a key decision for the board to resolve with its staff:

Phase

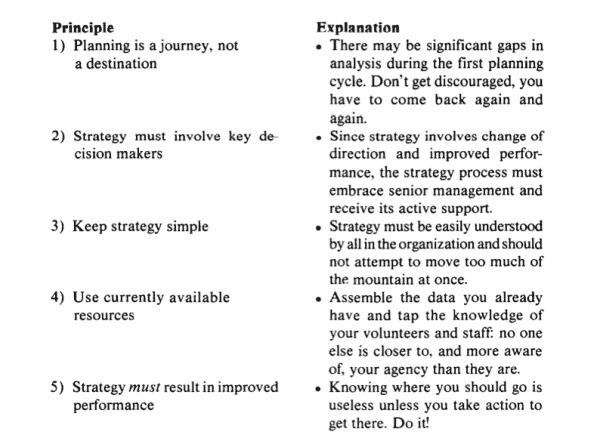

It is essential to the success of the planning process that the board make these key decisions during the appropriate phase. For example, you can’t have the chairman uncommitted to the planning process until halfway through the exercise and expect anything but failure as a result In the planning process, you should understand and adhere to the following principles of planning:

Phase One: Planning to Plan

In this first phase, whether you are a staff member or volunteer, you are trying to determine whether a strategic planning exercise would be appropriate or useful for your organization. You’ve heard about strategic planning from a friend, you’ve read an article like this one, or you have attended a workshop on strategic planning like the one sponsored last November by The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy. You are acutely aware of the problems your organization is, or will be, encountering within the next 20 years as the voluntary sector evolves. So you talk to other staff or board members to understand more fully the dimensions of the problems you perceive and learn of some you haven’t seen. You then make a presentation to the board based on your early thoughts about the problem areas.

The board thinks it is worth further consideration so a steering committee is formed to do some preliminary data collection and analysis. A proposed work plan is developed, showing what is to be done by whom over what period of time, and is submitted to the board. At this point, the board must become fully committed to the strategic planning process, otherwise the plan may be ignored once completed. A strategic planning task force is now recruited from key decision makers throughout the organization. (Be sure to include some members who usually say “no” to anybody else’s suggestions.)

Phase Two: Analysis and “Strategizing”

In this second phase we are seeking to “define the forest”. We have to analyze where we are before we can understand how and where we should proceed.

“Strategizing” as previously defined is the construction of alternate scenarios for the future which are based on current strategic analysis. Our planning task force does the initial “strategizing” at this point and presents the scenarios to the full board for its understanding and assessment during the third phase. To do this they must look at all the possible outcomes of the current position because the future they least anticipate or want to occur, probably will. However, they must first complete the analytic part of the process and consider the implications of that analysis.

Analysis

The “forest” can be divided into four sections, as shown in Figure 1. Stakeholdersare all those having an interest in, or influence on, the direction/success of the organization. It is an enlarged “shareholder” concept which includes donors, recipients, governments, and the community at large. Stakeholders sometimes make confusing or conflicting demands on the organization to meet their own expectations. An understanding of these concerns, demands and expectations is crucial to determining potential new directions and calculating the trade-offs involved. The easiest way to discover their concerns is to ask them. If a major donor is adamantly opposed to the organization’s pursuing an important new service opportunity, you have to decide whether the benefits of the new service outweigh the financial loss. The dual objectives of this section are to identify all stakeholders and to understand clearly what their expectations are.

An analysis of the operating environment is the next step in defining the forest. Here you must consider the forces operating in the demographic, social, economic, political and technological areas which will have an impact on the organization’s future and in what way. By understanding these forces or trends you will see more clearly the opportunities and the threats facing your agency. For example, if the agency’s “product line” is service to victims of a disease for which a complete cure may soon be found you had better include that environmental factor and its implications in your analysis of the future.

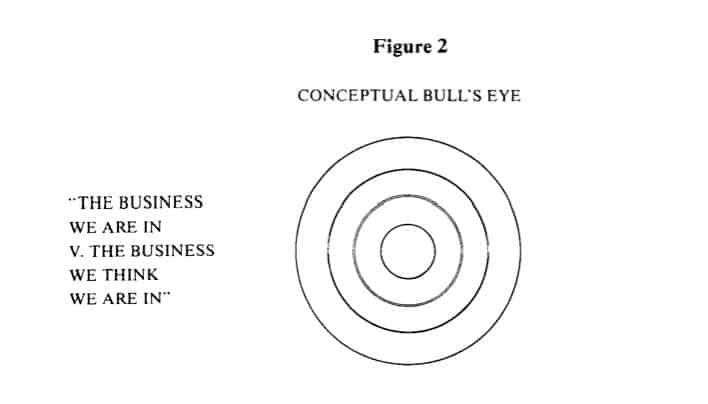

Figure 2

To gain an understanding of the agency, you should now look at the other agencies operating in the same voluntary sector(Figure 2). While you may feel you are all alone in the centre ring, the true size of your sector is much larger. Any agency in any community competes with other apparently unrelated agencies in terms of duplication of services, demands on volunteers, or funding sources. You have to understand what the others are doing, or planning to do, so you can shape your own agency accordingly. There is no point in planning to establish a volunteer recruitment program or mounting a fund-raising drive if another group is approaching your potential volunteers or donors at the same time. Conversely, if you have knowledge of sector intentions and can launch your program first, you have a real advantage.

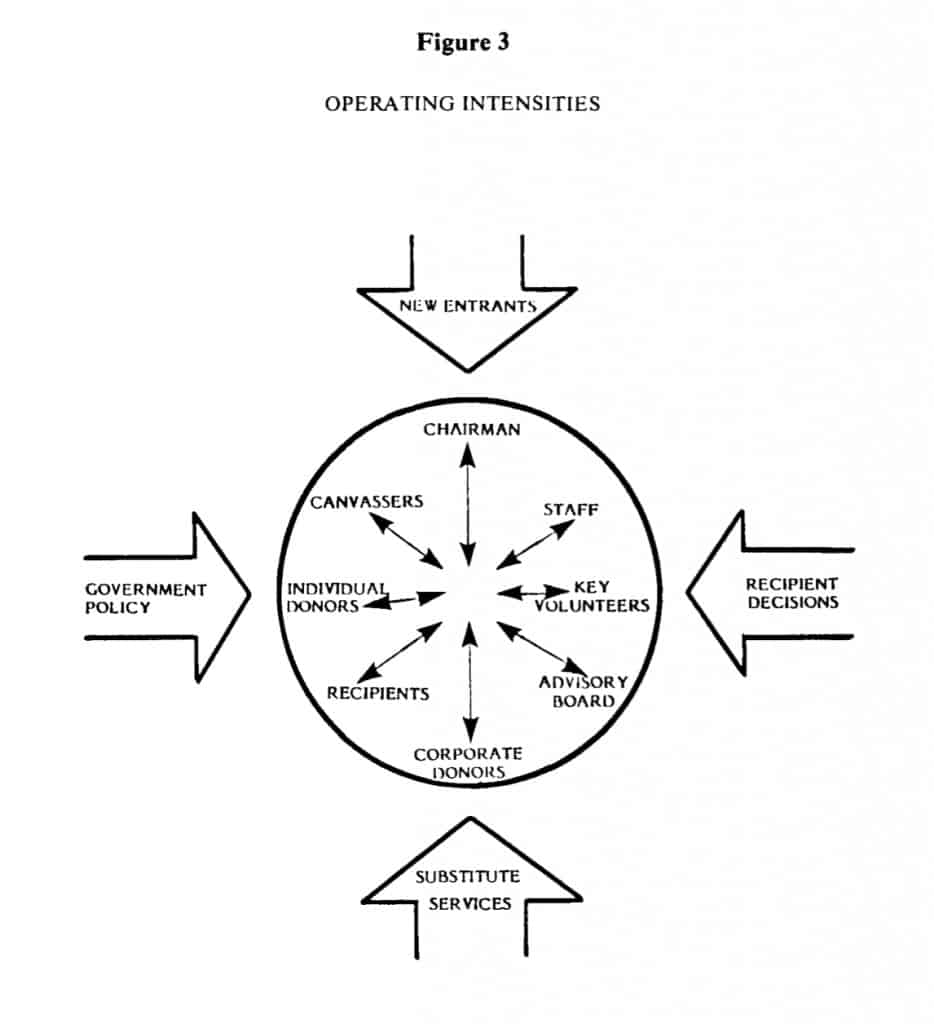

Another important segment of the voluntary sector analysis is the assessment of the possible actions of organizations outside the voluntary sector which will have an impact on the voluntary sector in general and on your group in particular. The operating intensity chart (Figure 3) shows the main external groups or areas of concern which will have an impact. For example, some level of government may decide to develop programs in your operating area; some current recipients may decide they want self-administered programs; some new group may decide they can do the same work, only better; or some group may offer substitute services which drain off volunteers, funding or clients. Continuous awareness of external factors affecting you and their implications for the agency are essential if you are to develop a strategy for the agency’s survival.

From this sectoral analysis you will be able to develop a list offactors critical to the success of all organizations operating in your sector. These key factors might be a strong volunteer base, high public profile and acceptance in the community, reliable funding sources and continuing demand for the services the sector provides.

The fourth and perhaps most difficult step in the analysis is a realistic appraisal of your own agency’s strengths and weaknesses. This strategic inventory must be as objective as possible since no organization has only strengths or only weaknesses. The most important areas to be considered are the keys to success identified in the sector analysis but there will be other areas for strategic inventory as well. Listing strengths and weaknesses will reveal several distinct advantages your agency has over others in its sector. These distinct advantages will be emphasized and reinforced in your strategy.

“Strategizing”

We have adapted the traditional planning process to place “strategizing” at this point. Ordinarily, strategizing occurs in Phase III and is done by the board as a precursor to the selection of the preferred strategy. In voluntary agencies, however, the task force itself is well equipped to outline the probable scenarios. Its members have been working closely with the analysis and they will be able to devise possible scenarios while it is still fresh in their minds. The board will, of course, also review the analysis and the preliminary scenarios so it can understand the strategic issues and make informed choices of preferred directions.

Based on the new knowledge of your own agency and its “forest”, you are now ready to start “strategizing”, i.e., developing a scenario that will get you out of the forest. Scenario building is done through a series of”what if” questions about the future. Typically, four scenarios are devised. The base case is: what would happen to the world and to your agency in 10-15 years if no change in your present direction occurred? The best case is: what if everything you wish to happen, happens? The worst case is: what if everything you fear will happen, happens? The optimal case is a realistic version of the future, falling somewhere between the base case-no corrective action—and either the best case or the worst case, depending on how you feel about your strengths and weaknesses and your ability to respond to challenge and to change. Generally, the optimal case provides the outline of a preferred strategy recommendation to the board.

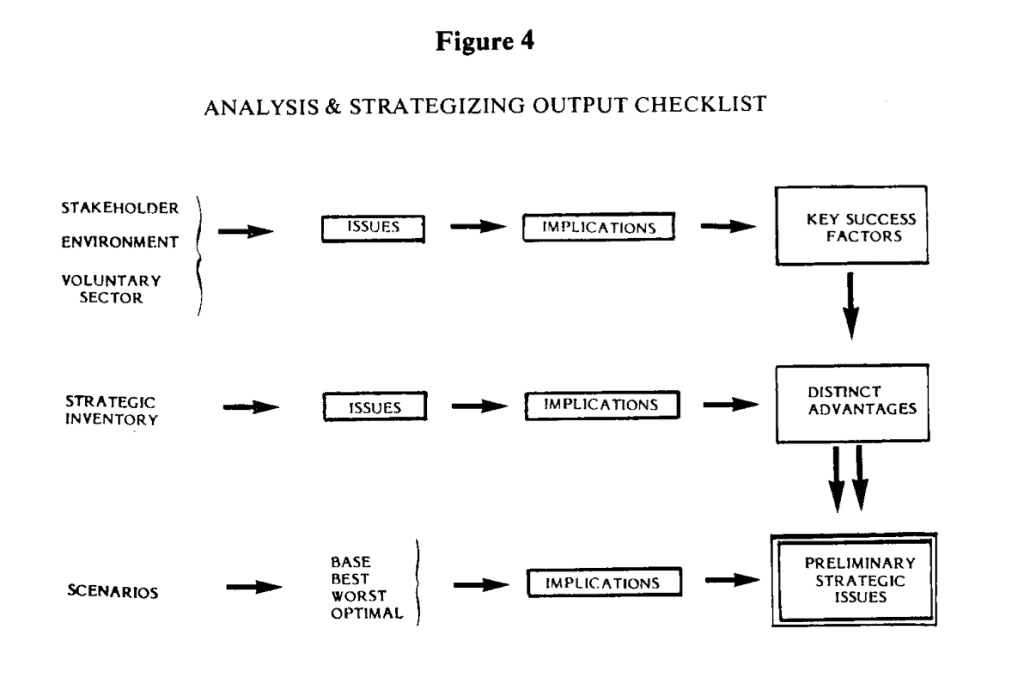

At the end of all this you can summarize a list of preliminary strategic issues you feel the board and the agency must face as they develop a strategy. Throughout this “strategizing” phase, it is absolutely critical to have the active involvement of key decision makers at all levels of the organization and all levels should be represented in the task force, to gain the value of their differing perspectives and knowledge. Those who must carry out the new strategy must feel they had a hand in creating it. Furthermore, there is an incredible amount of hard work and thinking to be done in this phase of planning and it can’t be done adequately by the chairman of the board, the executive director and a few members of the staff. Figure 4 is a flow chart of required outputs from this second phase of planning.

Phase Three: Strategy Formulation

In this third phase, the full board and the task force join together in a workshop setting to review the strategic analysis; to discuss the key success factors, various scenarios and preliminary strategic issues; and to create the optimal scenario which will become the preferred strategy for the agency. The workshop should be held over a two-day period in a setting conducive to focussing on the strategy rather than answering phones or dealing with mail. It can also be held in stages at night or over a period of weeks.

The importance of choosing the right people for the task force now becomes clear. It is much easier to get a group to concur with suggestions when the opinion leaders or chronic nay-sayers at all levels of the organization have been involved in the task force process leading to the recommendation. The opinion leaders on the task force will be able to explain the recommendations to the board rather than sniping from the tall grass after the board has made its decision and the board’s comfort level with the recommendation will be quite high since members will be assured that it arises from careful and appropriate consideration. This is called”obtaining closure”.

During the workshop, the board will review the evaluation and implication summaries for “stakeholder needs”, “environmental scan”, “voluntary sector” and “strategic inventory”. Then members will discuss their views of the key success factors, i.e., the distinct advantages flowing from that analysis. They will then be able to devise their own scenario which will lead to a revised list of strategic issues and priorities which the final strategy must address. The board wil decide how best the agency may respond to these strategic issues and the task force may then have to review and revise the agency’s mission, goals and objectives to reflect the realities the board foresees. The “preferred strategy” is the board’s collective understanding of where the agency is now and where it should be headed, of what it wants the agency to accomplish in its new direction and of the appropriate allocation of human and financial resources to that effort.

The second part of the board/task force workshop is devoted to setting up action plans to communicate and implement the new strategy. Proper communication of the strategy by and to the appropriate people is critical to successful implementation. Many of the stakeholders have not been involved at any point in the strategy-planning process, yet they have a clear interest in the future of the agency and thus in its strategic plan. A full identification of stakeholders at the beginnning of Phase II will help you to decide at the end of Phase III who needs to be told what and by whom.

Action plans will vary with different agencies but all plans will contain lists of what has to be done, by whom, when, and within what standards of performance. The board must assign these responsibilities and deadlines as quickly as possible, otherwise the strategy may just gather dust while everybody thinks somebody else is implementing it.

Phase Four: Implementation

This fourth and final phase is one of the most important but often the leastcompetently performed in the whole strategy cycle, hence the failure of many wellconstructed strategies. You may have created the ideal strategy for your agency, but it can still fail if you fail to measure how well you are doing (service effectiveness evaluation); tell yourselves and the community how well you are doing (volunteer/ community feedback); and have the flexibility to change your goals and objectives as conditions require (continuous planning process).

Part of an effectiveness evaluation is an understanding of how well you are proceeding past your planning”milestones”. Analyses of revenues and expenditures, volunteer recruitment and renewal, disbursement of funds, and achievement of the start-up tasks identified in the strategy, contribute to this understanding. More significant to the effectiveness evaluation is some objective assessment of the community’s wellbeing with and without your services. This assessment will reinforce the agency’s reason for existence and stated mission. An example of an agency in urgent need of this type of assessment would be a cod fishermen’s benevolent fund operating in a community with no cod fishermen.

Volunteer and community feedback are two essential elements of the implementation phase. Volunteers working hard on a “new look” operation may lose interest quickly if they’re not advised of early successes. Similarly, the community will welcome “good news” information about the revamped agency.

The final point about flexibility is particularly important for voluntary agencies which are beginning to plan strategically. The universe may not unfold as they expect, and they must not get trapped in a strategic plan which is no longer appropriate. If expectations about the future are not fulfilled you must be able to adapt to the new realities. For this reason, a continuing planning process involving an annual review of the mission statement, the goals and objectives, the trends and strategic issues, and the action plans and implementation milestones, is highly recommended.

Any prescription for successful strategic implementation6 must include the commitment of both the board chairman and the executive director to following the agreed upon strategy and action plans. The strategy must be simple, credible and communicated to the whole organization. The action plans and the resource allocation decisions must be consistent with the strategy. The passing of milestones and reporting must be monitored. A reward system must be created to recognize successful passing of each strategy milestone.

Summary

So there you have it! If you follow the guidelines for the four phases of planning; achieve the key board decisions for each phase; remember and apply the planning principles; finish the analytic phases by identifying key success factors, r1’jstinct advantages and strategic issues; get closure from the board on preferred strategy, mission, goals and objectives and implementation milestones and finally get some improved performance in your agency, you have been successful. Remember though, the first principle of planning: it is a continuous process and the first cycle will be full of gaps. Keep repeating the cycle annually, however, and you’ll be surprised how quickly the gaps close.FOOTNOTES

1. Walker, J.M., “Limits of Strategic Management in Voluntary Organization”,

Journal of Voluntary Action Research, July-September, 1983.

2. Kotler, Philip, Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations, 2nd Edition, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1982, p.76.

3. “Mission” is the basic purpose—the reason for being-of the agency. It answers the question: what are we trying to accomplish?

“Objective” is a major thrust the agency will have for a substantial period, e.g., volunteer recruitment, extension of service to another region, establishing a capital fund.

“Goal” is an objective made specific in terms of size and time and assignment of responsibility.

4. Connors, Tracy, editor, Nonprofit Organization Handbook 1980, New York, McGraw-Hill, p.2.24.

5. “Strategizing” is the construction of various scenarios for the future based on current knowledge and strategic analysis of emerging trends, opportunities and threats.

6. Collier, Don, “How to Implement Strategic Plans”, Journal of Business Strategy, Winter 1984, p.92; and Lauenstein, Milton, “The Strategy Audit”, Journal of Business Strategy, Winter 1984, p.87.

W. LAWRENCE BRYAN

Strategy Consultant, The Duneagle Group