Summary: On the one hand, Collective Impact is deceptively simple: a clearly defined framework with three pre-conditions and five conditions and a growing body of experience about how such an approach can effectively address complex social issues. But as is often the case, the devil is in the details, and Liz Weaver provides a detailed analysis from an implementation perspective based on the 12 years’ experience that Tamarack has had acting as the backbone organization for Vibrant Communities and now playing the lead role in Canada in providing support for the implementation and development of Collective Impact networks across the country.

It has been just over two years since the first article about Collective Impact (Kania & Kramer, 2011) was published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review. Little did the authors, John Kania and Mark Kramer of FSG, realize how quickly the Collective Impact framework would catch on and, in many ways, go viral as a framework for collaborative planning tables trying to tackle some of the most complex issues facing communities.

There are many who say that the Collective Impact framework, consisting of three preconditions and five conditions, is exactly how many collaborative tables are already operating and that there is nothing really new or innovative in the design. Indeed, staff at Tamarack: An Institute for Community Engagement viewed the Collective Impact framework as a clear and concise way of describing the place-based poverty reduction efforts called Vibrant Communities that we have been advancing in Canada over the past 12 years.

But there is something different, unique, and challenging about Collective Impact. Its application, employing all five conditions effectively and simultaneously to drive change forward, requires collaborative tables to work simultaneously within two spheres – both from an organizational impact perspective and also with a systems level lens. This article provides a frame for understanding and employing Collective Impact as an approach to collaborative community change from an implementation perspective. It will look at both the promise of effectively applying the framework and also the peril in its misapplication.

Communities are complex

It should be noted that Collective Impact works best when the issue being tackled is complex and dynamic. Complex issues are such that they have multiple root causes, there are many players already at the table, and there may not be a direct line between an intervention and a result. Communities are equally dynamic and complex. The leadership in communities is always in flux, the connections between the different players can vary over time, and sustaining and building trusting relationships to enable different sectors to work well together is often challenging. Collective Impact, as a framework, seems to work well in these complex and dynamic situations. In “Embracing Emergence: How Collective Impact Addresses Complexity,” Kania and Kramer (2013) identify three specific strategies to employ in dynamic contexts: collective vigilance, collective learning, and collective action. They recognize the tension between being flexible and responsive while continuing to stay focused on the agreed end goal of collective action. Collective vigilance, learning, and action help to push the collaborative tables from talk into action. Effective implementation of Collective Impact therefore requires people to be willing to work and do things differently as they very consciously move toward Collective Impact.

The pre-conditions for Collective Impact

Collective Impact, as a framework for community change and impact, consists of three pre-conditions and five conditions. The three pre-conditions include having influential leaders, a sense of urgency for the issue, and adequate resources. These necessary preconditions are often overlooked but have been foundational to many of the Vibrant Communities initiatives across Canada. Finding and engaging influential leaders can be critical to Collective Impact approaches. These champions bring with them a number of strategic assets, including a sphere of influence that can be tapped for resources and funding and connections to broaden the network and lend credibility to the collaborative effort. A collaborative effort that effectively engages influential leaders and their spheres of influence can ramp up more quickly.

The second pre-condition is the urgency of the issue. For any type of collaborative change effort to get traction, the issue being tackled has to be perceived as either urgent or important to the community. This can be challenging, as there is so much “noise” and so many important issues out there in communities. Urgency identifies the need for data to inform the issue and as a key strategic tool. Consider the example of low birth weights of newborn babies. There is significant evidence linking low birth weights to educational achievement. If low birth weight children do poorly in school, they are less likely to graduate from high school, enter post-secondary education, and/or be successful in the workforce. Many low birth weight babies are born into families with economic and social disadvantages and face challenges throughout their lives. But how often is the issue of low birth weight considered a key economic challenge for a city as a whole and not just among those working directly in public health or social services? Urgency of the issue highlights the important work of utilizing data and research evidence to “connect the dots” and make the case that upstream interventions will have positive downstream consequences.

The third pre-condition for Collective Impact is adequate resources. The collaborative table needs to determine the appropriate level of resources required to effectively do this work. Collective Impact efforts operate at the systems-change level and require the engagement of multiple partners and multiple strategies. Many collaborative tables undervalue what it takes to make effective progress within this sphere. A common strategy for many organizations is to try and undertake collaborative efforts as an add-on or a “side-of-the-desk” activity. As well, there is little funding available in Canada to resource the administrative or backbone functions to support the effective multisector collaboration required for Collective Impact, as these are often not considered to have direct impact on issues. Adequate resources must be in place in advance if Collective Impact initiatives are to succeed.

The five conditions of Collective Impact

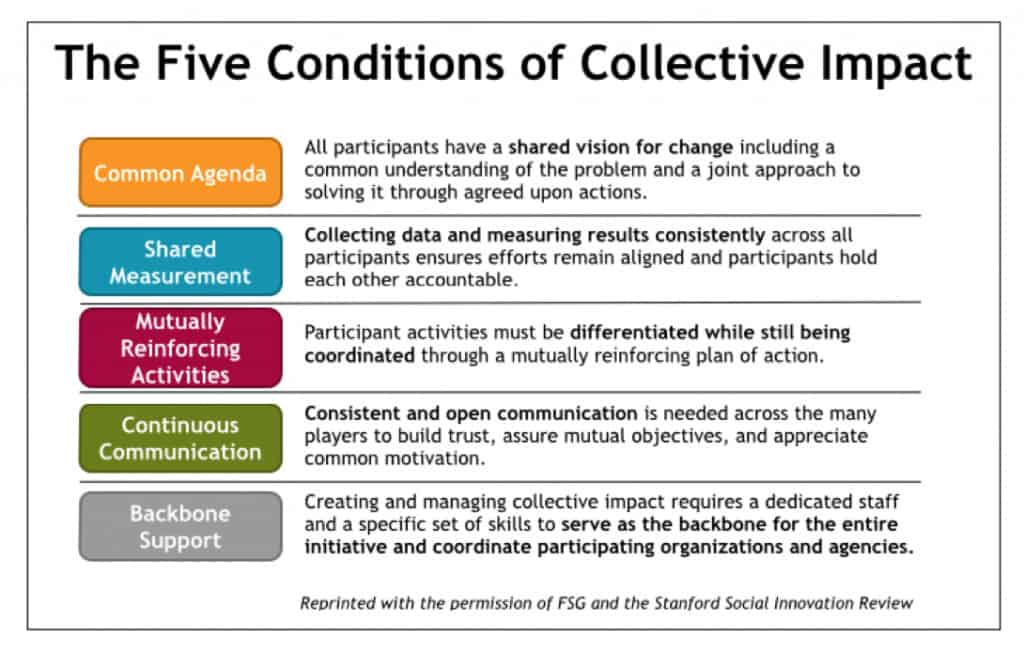

Much has been written about the five conditions of Collective Impact: a common agenda; shared measurement; mutually reinforcing activities; continuous communications; and, a backbone infrastructure. The articles “Collective Impact” and “Channeling Change: Making Collective Impact Work” (Hanleybrown, Kania, & Kramer, 2012) provide a useful overview of these five conditions as well as examples of collaborative efforts effectively employing the framework.

The first three conditions—developing a common agenda, shared measurement, and mutually reinforcing activities—are inextricably linked. The common agenda sets the broad frame that all partners agree to act within. It should include an aspirational statement that describes an outcome that is beyond what any single partner can achieve alone. The goal of “Making Hamilton the Best Place to Raise a Child” drives the work of the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction, but is also a call to action that the Roundtable and community partners use to consider whether their efforts are indeed enhancing the lives of children and youth in the city. The common agenda also needs a clear statement that provides a focus for the measures of change the table envisions as well as the priority areas of its work. Finally, a common agenda should include the principles as to how the partners agree to work together to drive change.

The statement setting out a clear measure for change links directly to the second condition of shared measurement. Shared measurement involves all partners in reaching an agreement on the set of indicators or measures that they will all contribute to and use to ultimately demonstrate their progress. The Calgary Homeless Foundation’s 10 Year Plan to End Homelessness 2008-2018 has identified that it is striving to ensure that “by January 29, 2018, an individual or family will stay in an emergency shelter or sleep outside for no longer than one week before moving into a safe, decent, affordable home with the support needed to sustain it” (Calgary Homeless Foundation, January 2011 Update). The Foundation has developed a shared measurement strategy that ensures that each partner around the table knows what progress is being made and what their contributions to this change are. Similarly, the Our Kids Network in Ontario’s Halton Region has developed a data portal that allows its community partners, parents, teachers, and anyone concerned with the success of children in that region to access open source data that describes how children and their families are doing in 21 neighbourhoods. These two examples shine a light on the enormous potential of shared measurement to drive community change.

This collaborative approach leads naturally to mutually reinforcing activities. To achieve progress on a common agenda and shared measures, a coordinated set of actions is required that involves multiple stakeholders across a community. For example, if a community is seeking to increase high school graduation rates, it needs to engage strategic partners including the school board, parents, students, community support organizations, and employers. Isolated strategies have limited impacts; however, when these strategies are integrated and coordinated, it becomes possible to leverage the skills and resources of many players to successfully achieve impact.

The final two conditions required to achieve Collective Impact are continuous communication and a backbone infrastructure. Again, these elements are linked and integral to Collective Impact. Ensuring that multiple partners are strategically engaged requires a strong focus on communication. The partners need to know the impact of their contributions as well as those of others in the group, and they need to be able to mutually identify, in a timely way, those strategies that are having the greatest impact. Continuous communication is also needed to create community engagement and buy in. Sometimes effective strategies will emerge in the most unlikely places. When the broader community is engaged in the success and achievement of the project, they begin to work in a concerted way. This is often where the backbone can be most potent. Backbone infrastructure can help focus the Collective Impact effort on moving forward by keeping an eye on the overall vision and by understanding and tracking the strategies being employed. They can bring partners to the table around shared measurement strategies and mutually reinforcing activities. Working towards systems level change, the backbone infrastructure can also facilitate the development of the collective voice needed to identify and advocate for potential policy shifts.

The promise of Collective Impact

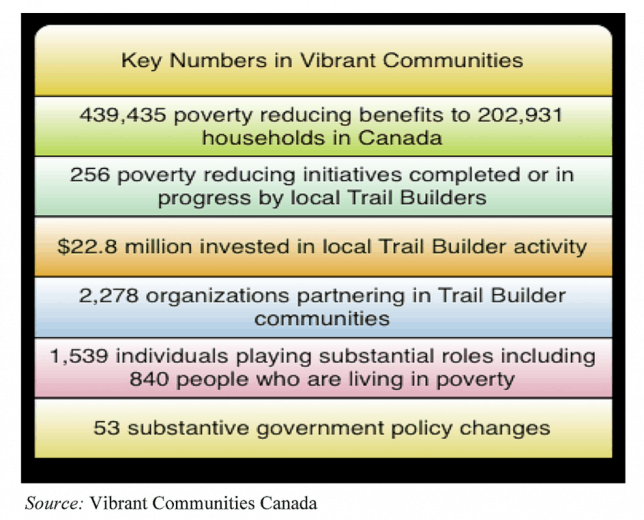

Collective Impact efforts are still in their early days, but there is a growing understanding about the value of applying Collective Impact as a framework to community change efforts and there is emerging evidence of the impact of these initiatives in both Canada and the United States. Vibrant Communities Canada, funded by the J.W. McConnell

Family Foundation with Tamarack and the Caledon Institute of Social Policy as key strategic partners, was collectively able to positively impact the lives of 202,931 households living in poverty in 13 cities in its first ten-year phase through a broad range of assets that includes: new skills & resources; improved social ties; and, direct benefits that enhance life circumstances for those living in poverty. In addition to the direct poverty-reducing initiatives of this work, many of the local poverty roundtables also influenced the design of provincial poverty strategies, which resulted in 53 substantive policy changes.

In the United States, collaborative efforts that focus on educational achievement across the lifespan such as the Strive Partnership and the Seattle Roadmap Project are showing significant progress on a wide-range of indicators that are impacting children and improving school success. These and other Collective Impact initiatives are being documented as case studies by FSG and Tamarack to better understand how this approach actually works from an implementation perspective, and these are readily available on the websites listed at the end of this article.

The peril of Collective Impact

As much as Collective Impact approaches are showing a lot of promise, there are also some warning signs. As with any framework, there is scepticism by some that Collective Impact is nothing new, that it is merely a re-packaging of old ideas about collaboration, and that collaborative efforts using Collective Impact will not achieve the outcomes they promise or desire. What is clear, though, is that the current design and delivery of services through individual organizations are not moving the needle on many of the most vexing issues facing our communities, such as homelessness and poverty.

Another warning sign is the idea that every collaborative effort needs to use the Collective Impact framework as a way of organizing. The Collective Impact framework is best suited to collaborations focused on a complex community need, problem, or opportunity. It requires adequate human and financial resources to be implemented effectively. It also requires the commitment by all participants that a Collective Impact approach is the most appropriate. The fact is, not every collaborative effort either has adequate resources or can operate effectively within a complex system that requires a high degree of commitment and coordination. Some collaborative efforts are necessarily more narrowly focused with shorter-term goals and commitments. These don’t need a Collective Impact approach.

That being said, the likelihood of success of most collaborative efforts can be improved if one or more of the conditions defined by Collective Impact are used. Asking the questions “What measures will show that we are making progress?” or “How can we improve communications across partners?” are simple strategies that will undoubtedly enhance collaborative work. While not everyone who becomes interested in Collective Impact or attends a workshop adopts the framework, we believe that many come away with new ideas and understandings about collaborative work and community engagement.

It is also perilous for funders to ask collaborative tables to champion Collective Impact without understanding and investing in the backbone infrastructure. The backbone infrastructure is critical to aligning partners and purpose in Collective Impact. Without staff and key leadership support, Collective Impact efforts can flounder. In the early stages of Collective Impact, there is a great deal of negotiation that is required simply to bring partners to agreement around the common agenda, shared measurement approach, and mutually reinforcing activities. This is definitely not business as usual, but rather a new way of working and being that requires time and effort. A strong backbone is instrumental in continually moving the process forward, getting it unstuck, and holding the agreements of the engaged partners. This is an essential element of the process.

In the article, “Understanding the Value of a Backbone Organization in Collective Impact” (Turner, Merchant, Kania, & Martin, 2012), the authors tackled many of the preconceived notions about the role of backbone organizations. Organizations cannot simply appoint themselves to the backbone role. They work in service of the collaborative table. If a group declares itself as the backbone and, in doing so expects to advance its own agenda, then typically we will see partners vacate the table. Effectively advancing a Collective Impact initiative requires relationships of trust amongst participating partners. So, when organizations participating in a Collective Impact initiative act in ways that are primarily self-interested, they often fail to create the relationships of trust needed to ultimately be successful. It is perhaps this whole question of the most appropriate approach to the governance of Collective Impact initiatives that needs to be the subject of further thought and reflection as more organizations and individuals become engaged in these processes.

Final thoughts

Collective Impact suggests a useful set of conditions that provide simple rules for complex interventions. The devil, as they say, is in the details, and the way in which these conditions are implemented will affect the success of the Collective Impact framework in its ability to move the needle on a community challenge or need. As collaborative initiatives continue to emerge and apply the Collective Impact framework to their work, we continue to watch for the most effective tools and techniques that will improve the probability of success. There are some promising results, even in the early application of Collective Impact. But there will also be some colossal failures as the conditions essential for Collective Impact are unevenly and incompletely applied.

During the first ten years of Vibrant Communities in Canada, we learned a lot about how local context informs application. Many of these lessons were shared across the “Poverty Reduction Community of Practice” that Tamarack hosted and which helped to build the collective capacity of all partners, but this was not by accident and required considerable effort by the coordinating teams and those most directly involved. FSG and the Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change have now created a Collective Impact Forum where they hope to capture and share how communities are applying Collective Impact. Tamarack is the Canadian partner for these efforts, and we will continue to listen, watch, and engage with communities as they take on the challenge of systems change using the Collective Impact framework.

While Collective Impact is showing promise and starting to deliver results, this approach is still in its early days, in large part because the problems that we are trying to tackle are large, complex, and challenging. While our society often seems to demand quick action, instant solutions, and immediate evidence of outcomes, in my own estimation Collective Impact initiatives require up to five years to fully develop and to begin showing concrete results. The longer-term nature of these initiatives needs to be understood by communities, participants, and funders because it requires commitment, investment, and determination. But the payoff will also be long term, as root causes are addressed, lives and systems are changed, and communities thrive.

Conclusion

The promise of Collective Impact lies within the simplicity of the approach or framework– three preconditions and five conditions—that, when executed effectively, can lead to progressive and substantial community impact at scale. The conditions seem both obvious and, in many ways, intuitive: a common agenda driving collective action, shared measurement to assure progress is being achieved, mutually reinforcing activities that ensure alignment and contribute to the goals, continuous communications, and a backbone infrastructure that coordinates and supports the collective efforts.

The simplicity of a Collective Impact approach belies the challenges that are embedded in the execution of working collectively on a complex community-change issue. Many organizations and collaborative planning tables think they are implementing collective impact when they focus on one or two of the conditions or include one or two sectors in their efforts.

This is not the intent of Collective Impact. The intent and innovation of Collective Impact is in implementing all five conditions in a focused and measured way with the intent of moving the needle (increasing or decreasing) on a complex community problem like poverty, educational outcomes, obesity, or neighbourhood renewal. The partners engaged have to believe that the collective effort will have the capacity to drive the change. Collective Impact is about working differently. It is about understanding the complexity and nuances of the problem and using data intentionally and as a driver toward innovation and results.

That is also the peril of Collective Impact. Current systems and structures create barriers to the effective implementation of the five conditions of Collective Impact. These barriers include funding mechanisms that are short-term and focused on individual organizational outcomes; the need to get credit for the collaborative work; and, internal organizational structures that have a low tolerance for risk. Implementing Collective Impact also requires a different set of leadership skills.

Collective Impact is gaining worldwide popularity as a framework that can have significant impact in shifting problems that seem to be intractable. But there is also a healthy scepticism of it as an approach. As it continues to gain traction, it will be important to continue to gain greater clarity about what Collective Impact can effectively achieve and what it takes to succeed.

Websites

Collective Impact Forum: www.collectiveimpactforum.org/ FSG: www.fsg.org

Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction: http://hamiltonpoverty.ca/ Our Kids Network: www.ourkidsnetwork.ca

Strive Partnership: www.strivepartnership.org

Seattle Roadmap Project: www.roadmapproject.org

Tamarack: An Institute for Community Engagement: www.tamarackcommunity.ca

Vibrant Communities Canada: www.vibrantcommunities.ca

References

Calgary Homeless Foundation. (2011, January). 10 Year Plan to End Homelessness 2008-2018 (p. 3). URL: http://calgaryhomeless.com/assets/10-Year-Plan/10-year-plan- FINALweb.pdf [April, 2014].

Hanleybrown, F., Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2012). Channeling change: Making collective impact work. Stanford Social Innovation Review. URL: http://www.ssireview.org/blog/entry/channeling_change_making_collective_impact_work [April, 2014].

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011). Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. URL: http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact [April, 2014].

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2013). Embracing emergence: How collective impact addresses complexity. Stanford Social Innovation Review. URL: http://www.ssireview.org/blog/entry/ embracing_emergence_how_collective_impact_addresses_complexity [April, 2014].

Turner, S., Merchant, K., Kania, J., & Martin, E. (2012). Understanding the value of backbone organizations in collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. URL: http://www.ssireview.org/blog/entry/understanding_the_value_of_backbone_ organizations_in_collective_impact_1 [April, 2014].

Liz Weaver is the Vice President of Tamarack—An Institute for Community Engagement, where she leads the Vibrant Communities Canada team and provides coaching, leadership, and support to community partners across Canada to utilize a Collective Impact approach to community development. Liz brings more than a decade of experience to this work and is recognized for her strength and experience in translating theory into practice. Email: Liz@tamarackcommunity.ca .