This article was developed from a presentation to the Convention of the Canadian Society of Association Executives in Winnipeg, August 28, 1989.

On corporate giving …

“As a substitute for giving by broad masses of the people it has always been a delusion…. A good many third sector institutions the last few years believed that you can build a corporate constituency that gives you the money you need. That’s wishful thinking.

By and large, you have to build a mass constituency and believing that you can escape that very hard work by becoming a “kept woman” of a few corporations is not going to work.

You cannot hope to get corporate support unless you have the broad base of individual support. It is a delusion that you can go to IBM and say, “Give us money because we are so poor at raising money.” …Those big corporations are not supporting need-they’re supporting performance. And so many of my friends in nonprofits don’t understand it They believe you can go to the Exxon Foundation and they’ll bail you out because you’re incompetent. Exxon Foundation will give you money because you deliver results. And for that, you have to have your own donor base.”

– PETER DRUCKER

Introduction

Before focussing on some of the impediments to increasing the amount of money available from corporate giving (about eight cent of total donations) we should be aware of some of the pressures now being felt in the corporate world that limit the amount of time and thought that corporate executives will, or can, give to philanthropic activity. We should also look at some of the changes in the charities field itself which are adding to the difficulties corporations encounter when they deal with the philanthropic sector.

Impediments to Corporate Philanthropy

International Competition

More than ever before corporations are competing on a global basis, not just for foreign markets, but at home as well. The changes in the auto industry are perhaps the most dramatic illustration of this but it is replicated in all areas of corporate activity. The Free Trade Agreement with the United States is part of this process as Canada adjusts to new realities in international trade. Jack Fraser, Chief Executive of Federal Industries Limited since 1978, stated in the Globe and Mail’s Report on Business (February 1989), “The global situation makes it very difficult to control one’s local environment There was a day, if you controlled your market, you could simply pass your price increases to your customers. You cannot today because the Japanese or someone else will come in and grab your market”.

Alexander Aird and James Westcott write in an article titled “The Boss Under Fire” (Report on Business Magazine, February 1989), “In the 1980’s chief executives have faced the most competitive markets in history because of falling tariff barriers and a re-arrangement of the world economic order in favour of the Pacific Rim”.

Friendly and Unfriendly Mergers and Takeovers

Diane Francis writes in Controlling Interest (MacMillan of Canada, 1986), “This country’s best and brightest have been preoccupied with fancy financial footwork rather than the type of technological innovation that contributes to a nation’s wealth”. Mergers and takeovers are having a twofold impact. First, chief executive officers have to be concerned not just with profits but with ensuring that their companies do not become vulnerable to takeover. Recently Imperial Oil, Nova, Molson, Maclean Hunter, Dofasco and PWA Corp. have initiated takeovers of other companies. Second, as part ot this process there is a growing concentration of ownership. Diane Francis also noted that “Only 20 of Canada’s 400 largest non-fmancial corporations are widely held; some 380 have a shareholder with at least 15 percent of the stock and in 374 of these, a controlling interest of at least 25 to 30 percent is held by a family or conglomerate”.

Technology

Another significant change taking place in the corporate world is rapid technological change. Aird and Westcott write, “New technology can make some businesses obsolete overnight Witness the effect of fax machines on telex seiVices, or the threat that fibre optics poses to the transmission of electronic communications by cable. No one is immune. Manufacturers must constantly search out new technology that can give them an edge in the marketplace; financial seiVice firms require the latest computer systems to keep ahead of their competition in their information-intensive business”.

A Changing Society

In 1960, one in 10 Canadians had some post-secondary education; it is now one in three. The public has become more sophisticated and less likely to develop the “product loyalty” of the past. “Canadians today are less fatalistic and more likely to believe that they can be the authors of their own destiny”, stated Michael Adams, Head of Environics Research Group in an address to the Laurier Institute. This makes the job of the corporate leader much more complex, as do issues like the changing role of women, minorities, and the disabled in the work force, and the increasing move to an urban society. The job of the corporate leader has become more complex and internal communication has required new approaches replacing the traditional top-down method.

Increasing Regulation

In responding to a questionnaire developed by Aird and Westcott,

“Forty-five percent of CEO’s believe that the ability of Canada’s leading companies to influence their environment is decreasing-they feel less in control of their world. That is explained by the growing influence on business of a variety of outside forces, from consumer groups, government regulations and environmental organizations to corporate raiders and demanding investors”. Despite a ConseiVative government in Ottawa, CEOs think government is now exerting more pressure on them.

Changing Attitudes and Behaviour

The Changing Role of the CEO in Donations and Voluntarism

There is little question that in the past the CEO was often the key decision maker when it came to donations. In 1975, Samuel Martin (Financing

Humanistic Service, McClelland & Stewart) .noted: “In over 80 per cent of the companies, either a director or the clli((f executive officer setVed on the donations committee and, in 58% of the cases seiVed as chairman”.

Martin went on to note with some surprise that ”Time and time again, the research team was impressed by the disproportionate interest of high level executives in decisions involving relatively insignificant dollar amounts, in comparison with the large size financial transactions normally handled by top level executives”.

…….

However, given the pressures on the CEO, a decade later Martin was writing, (An Essential Grace, McClelland & Stewart, 1985), “Donation decision-making in Canada’s larger corporations is now in sharper focus. The process is formal, structured, organized and conservative”. The 1988 Annual Survey of the Council for Business and the Arts found that 72 per cent of responding companies had written donation policies, though a majority did not make these available to charities.

Whereas Martin had found in 1975 that in 32 per cent of his sample corporations a single person made donation decisions, a decade later this was down to 15 per cent Again in 1975, 80 per cent of the companies had either a director or the CEO serving on the donations committee but a decade later this was down to 64 per cent and, speaking of the role of the CEO in his most recent study, Martin wrote, “More often his involvement was in setting budget levels or establishing objectives for the contribution program. This contrasts with donation decision making in small business where, in only 20% of cases, more than one person was involved”.

However, when Martin asked the corporation to identify the single most important influence on the level of corporate generosity he found it was the board chairman or CEO. The personal convictions of the CEO and the chairman and altruism and tradition, were most often cited (second only to demonstrating corporate leadership), as a reason for making corporate donations. The 1988 CBAC Survey also found that, “It is clear from these responses (to the survey) that the CEO’s commitment to philanthropy is the single most important factor in determining the amount of money allocated to donations budgets. Seventy percent of the respondents indicated that the CEO’s commitment ranked either 4 or 5 on the scale of importance” (5 being the highest measure).

The Continental Bank (now Lloyds), in an essay in its 1984Annual Report entitled ”The Corporate Gift Horse”, stated ” … what fund raising veter ns remember as the ‘old boys network’, … remained a prevalent force into the 1980’s. Entrepreneurs and executives gave, sometimes on whim, occasionally from a sense of obligation, and often from outright generosity, but almost never in accord with a carefully planned corporate strategy”.

The role of the CEO in the donation-making decisions is changing from hands-on involvement to participation in the strategic aspects. ”The old boys network” is probably not operating as effectively today because CEOs, facing so many other pressures, simply do not have the time to make use of it!When we undertake to recruit corporate leaders for senior volunteer positions because of the credibility, prestige, and contacts they can offer, we need to be more realistic about the time we are likely to be able to command andthe number of fund-raising calls they will manage to squeeze into their busy schedules. However, there is still every reason to believe that if the CEOs give the time, and are themselves associated with generous corporations, they can still make the “old boys network” work!

A majority of corporate leaders is still committed to community setvice. This is shown by the answers to a question i .e Report on Business poll which asked CEOs how many hours a week they spent on community-related activities:

None 15%

1—3 hours 33%

4—9 hours 39% More than 10 hours 12%

Changing Attitudes to the Role of Corporations

While the changes mentioned help to prevent corporate executives from donating substantial time to charity there is one change that is working in favour of increased corporate philanthropy: there is a different expectation on the part of the public regarding corporate social responsibility. Who would have predicted a few years ago that we would see a book published which would apply “social accounting” techniques and publicly rate major United States corporations on a scale which measures “social responsibility”? (Rating America’s Corporate Conscience, published by The Council on Economic Priorities.) Obviously corporate giving is only one measure for “social accounting”. A partial listing of other measures includes the hiring of women and minorities, the composition of boards, environmental protection, investment in South Africa, workers’ health, product safety, the effects of business relocation, etc. Indicative of corporate concern for these issues is the growing number of corporations establishing board committees charged with the specific task of monitoring corporate social responsibility.

We know from the Decima Quarterly Report from 1986 that Canadians expect corporations to be involved in giving. The sutvey states: “8 out of 10 Canadians believe that corporations have a responsibility to provide financial support to charities and nonprofit organizations, with half of this group viewing it as a major corporate responsibility”.

If The Economist of April 14, 1989 is correct, things are not going to become any easier for corporations. It predicts: “during the 1990’s the business ethic is going to be questioned, criticized, sometimes even vilified; many of its supporters are in no position to answer back. … Producers in the1990’s are going to be seen as polluters, firers of others and liners of their own pockets…. The coming anti-business mood will probably be concentrated on big companies and moneymen”. If this prediction comes true, it may well stimulate further corporate interest in philanthropy. Reflect on how many corporations are now seeking to embrace the environmental movement, recognizing the major public concern that now exists for this issue.

Stimulated by concerns about image and the bottom line, another change has taken place in corporations. Whether it is to the long-term advantage of charitable activity is, and should be, a matter for debate.

Cross-Promotions and Sponsorships: The New Force

The corporate world in its quest for new and effective methods of selling products and/or improving company profiles has come to recognize the charities sector as a potential ally. Thus, in the late 1980s we have seen a major growth in cross-promotional advertising and sponsorships.

Both have been around for years-think of Texaco and its many years of involvement with the Metropolitan Opera-but have expanded in a major way in the last few years. There are those who see them opening up new financial opportunities and those who are concerned they will bring about the demise of disinterested philanthropy.

The Continental Bank’s essay “The Corporate Gift Horse” stated, “Applying the same discipline to the management of the corporate gift that is applied to other forms of spending is now producing a measurable benefit to the donor as well as the recipient”.

The Bank contrasted production costs for a 30-second TV commercial in 1984 ($80,000 to $250,000) with the cost of a single performance of a major theatre company (around $3,000) or a major dance company tour (about $100,000). It stated, “Given the potential impact of commercial-free pay television, videocassette recorders and TV-oriented video games to dilute audiences, it is hardly surprising that aggressive marketers are exploring new ways to put their name before the public”.

John MacFarlane, editor and publisher of The Financial Times, in a speech to the Annual Meeting of Philanthropoids of The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy in November 1988 [See (1989), 8 Philanthrop. No. 3, pp.

41-44] expressed serious reservations about mixing sponsorship, crosspromotions and philanthropy. He stated at the conclusion of his remarks, “To the extent that we devote our time and energy to bread and circuses-or should I say hamburgers and rock concerts-we ignore the real job: convincing people that they have an obligation to help their less fortunate neighbours…. If philanthropic giving has declined since the Sixties, it has done so because we have failed to make our case. It’s as good a case as it ever was, but in a world in which the proliferation of media has made communication, ironically, more difficult, we haven’t found effective ways to get our message across….And we never will if we allow ourselves to be seduced by the notion that buying is the same as giving”.

Some of us have rationalized sponsorships and cross-promotional activities on the basis that they make another pocket available—the marketing budget of a corporation-from which support might be gained as well as from the donations budget. Facts are beginning to emerge on corporate sponsorships that may cause some of us to revise this argument and think hard about MacFarlane’s point.

The 1988 CBAC Survey found that “Two-thirds of the respondents stated that if they decided to sponsor an organization to which, in the past, the company has given donations-sponsorship now replaces that support. This is because in 82% of cases sponsorships are, in fact, paid for out of donations budgets”.

In these cases sponsorships are not increasing the amount of money available to charity but rather the donations budget has been co-opted by the marketing department. Sponsorships have many more strings attached than corporate donations. For this, and possibly other reasons, donations are usually preferred by charitable organizations.

Periodically making headlines, and indicative of problems in this area, is the tension between organizations and corporations arising from differing views of how close their relationship should be and the internal debate as to when sponsorship and cross-promotional efforts begin to endanger the integrity of the charitable organization. Pollution Probe has recently experienced internal and external controversy regarding its involvement with the “Green” products of Loblaws. For corporations they are marketing issues. For charities they can be matters of principle.

The Growth in the Number of Charities/Requests

Recently I had a phone call from the senior staff fund raiser of one of Canada’s major charities expressing concern at the growth in competition for donations. In fact 58 per cent of CBAC Survey corporate respondents felt that their biggest problem was the increasing number of requests and 40 per cent also believed that the situation was being compounded by the “ever increasing number of charitable organizations competing for corporate funds”. Added to this is the fact that campaigns are growing larger and larger and are, therefore, seeking larger gifts.

There has been a significant growth in the number of charities in recent years. In the six and a half years to 1987, charities increased by 30 per cent The Institute of Donations & Public Mfairs Research (IDPAR) reports in its thirty-third survey of campaigns setting goals of $50,000 or more for private support (Fund Programs Planned, 1989) that this year there are 597 campaigns seeking $2 billion. Many of these will extend over a three- to five-year period. While this is down from the $2.5 billion reported in 1988, most of the decrease is accounted for by a decline in hospital campaigns. Campaigns not reporting to IDPAR and the many smaller campaigns must be added to this total.

Notwithstanding corporate complaints about the growth in the number of campaigns, I believe this has had, overall, a positive impact on corporate giving. For example, faced with the administrative problem of dealing with the new volume of requests, some corporations have reviewed, or are currently seriously examining, the way in which they are handling corporate philanthropy. As noted earlier, one effect is a less “hands-on” approach by the CEO. There is a growing body of evidence which suggests that corporations are beginning to think more “strategically” about philanthropy. A more professional business-like approach is being taken although most remain reluctant to disclose their donation policies.

There is also a growing resentment among corporate leaders of generous corporations of the substantial number of companies which are not pulling their weight and some indication that leading donors are now prepared to tackle the problem.

Discomfort With Giving Away Money

In an excellent booklet, Corporate Philanthropy: Issues in the Cu”ent Literature, published by the Yale University Program on Non-Profit Organizations, Seth M. Lahn notes, “Giving money away is a practice foreign to the normal orientation and operations of a large business corporation; it is thus not surprising that putting large-scale philanthropy into practice has raised a number of problems which both business contemplating a philanthropic program and non-profits seeking funds should understand”.

Corporate Views on the Management of Charities

Prompted by some stinging criticism voiced by a couple of senior executives about the way in which charities manage their affairs, The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy held a special workshop on this subject as part of its 1988 annual conference. While this resulted in beneficial discussion with some people from the corporate world who shared their concerns, the fact is that, with some 60,000 registered charities, some volunteers and donors are, unfortunately, going to have bad experiences.

(It is also true that those who wish to rationalize their failure to give often insist that it is only the inefficiency of charities that motivates them not to give.)

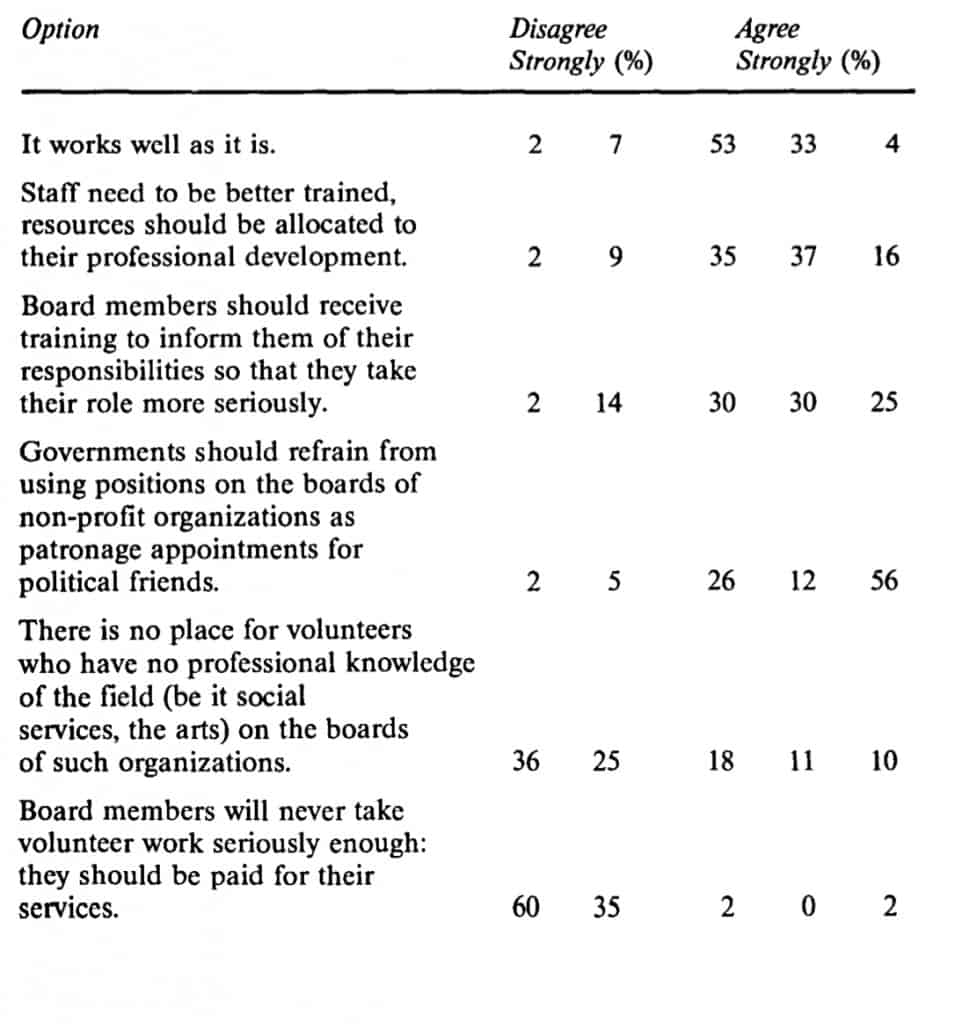

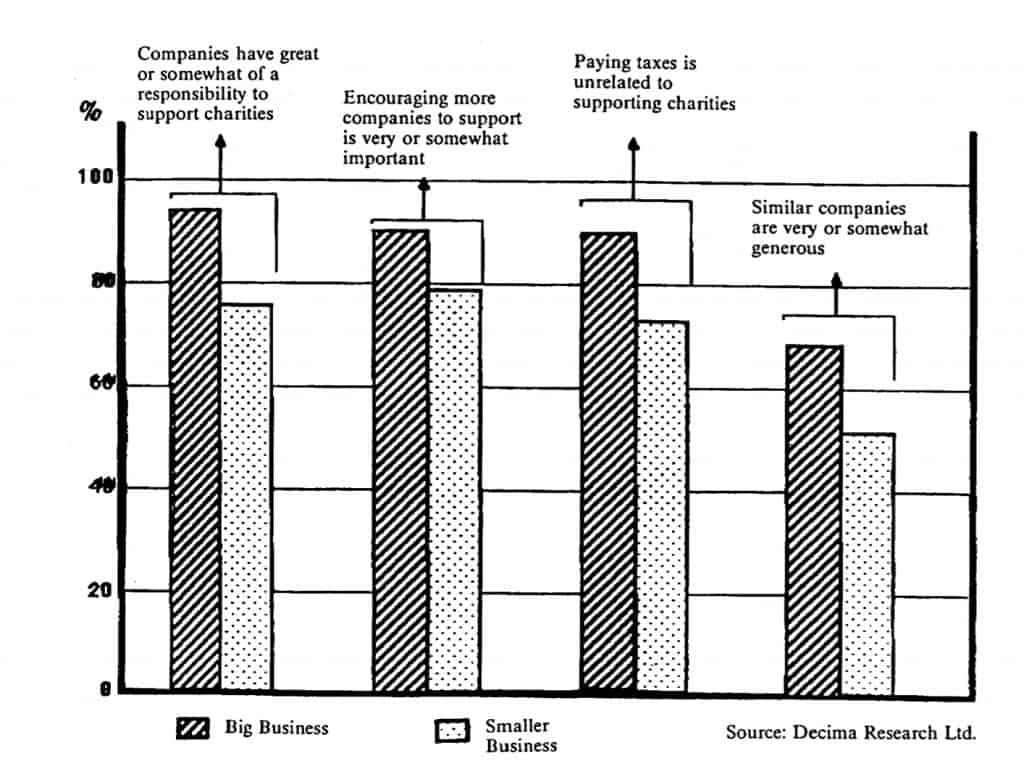

The CBAC Survey turned up interesting perceptions of the management of charitable organizations by professional staff and volunteer boards. Respondents were asked to rank the following options on a five-point scale in terms of what might be done to improve the effectiveness of this form of management:

Corporate Attitudes and Behaviour

While I think it is important to better understand real impediments and changing conditions affecting corporate giving, I do not intend to be an apologist for its current level. It is not what it should be. What we need most of all are advocates in the corporate world itself who will challenge some of the prevalent thinking. The CBAC Survey states, “Compounding the problem is the fact that 54% of the respondents feel their own donations budgets are labouring under restraints. A third pointed to the state of the economy which is weakening their own financial position”. This sounds as though, in general, corporate profits were going down. In fact the reverse is true. According to National Income Accounts profits have increased. These are the figures:

1985 $ 47.5 billion

1986 45.2

1987 50.5

1988 56.6

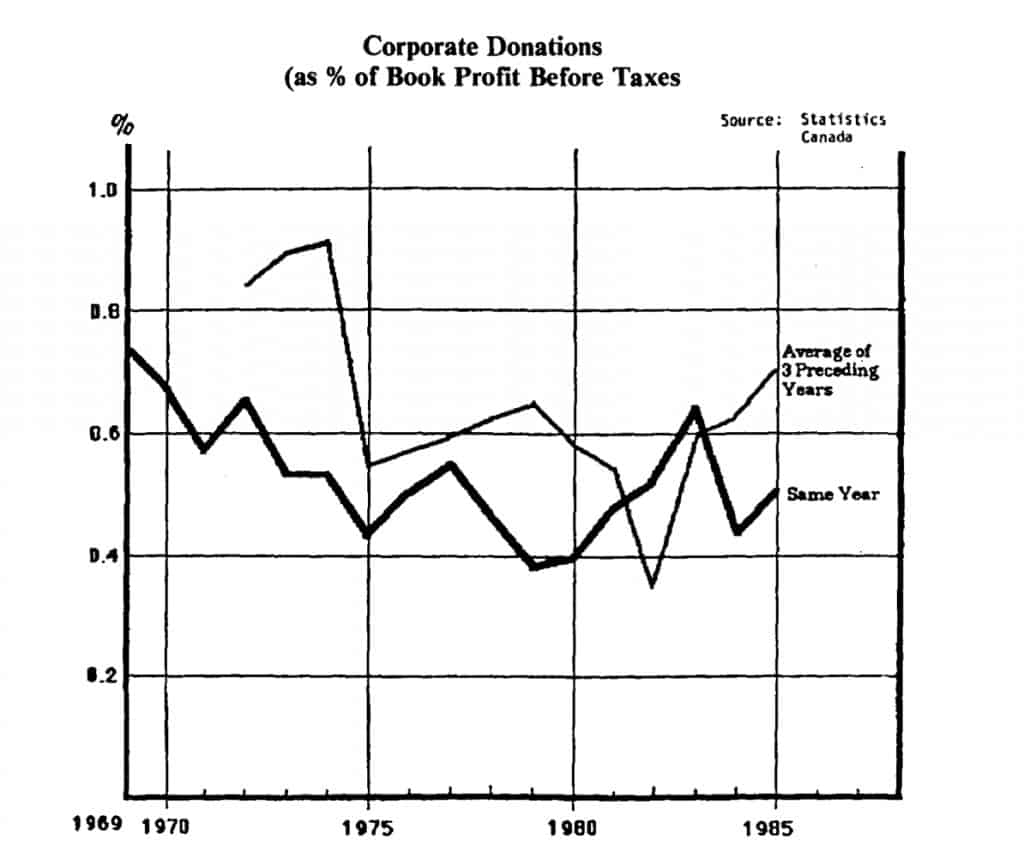

Whatever the new pressures on corporate donors, as the following tables and charts clearly indicate, many Canadian corporations are neither sufficiently philanthropic in practice nor aware of the need to become more generous.

The Good News

On the credit side the research clearly shows that:

– donations are growing

– attitudes to donations are highly favourable

– a majority of big businesses already have payroll deduction systems

– most companies support employee voluntarism.

The Challenge

Offsetting these positive opinions and trends the research also discloses:

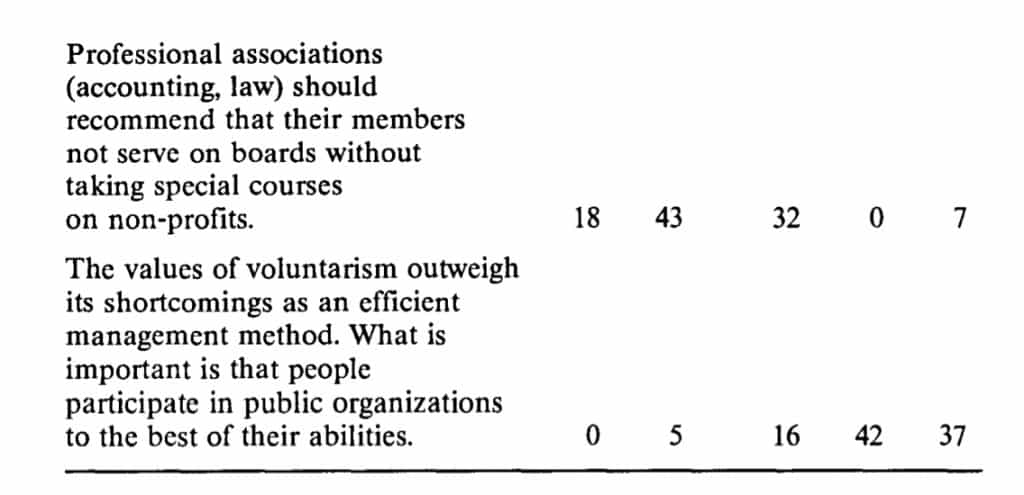

– donations, as a percentage of pre-tax profits, have declined steadily from over one per cent around 1960 to less than 0.5 per cent in

1987.

– about 40 per cent of companies polled believe donations of one per cent of profits would be too high

– most companies believe that similar companies are already generous

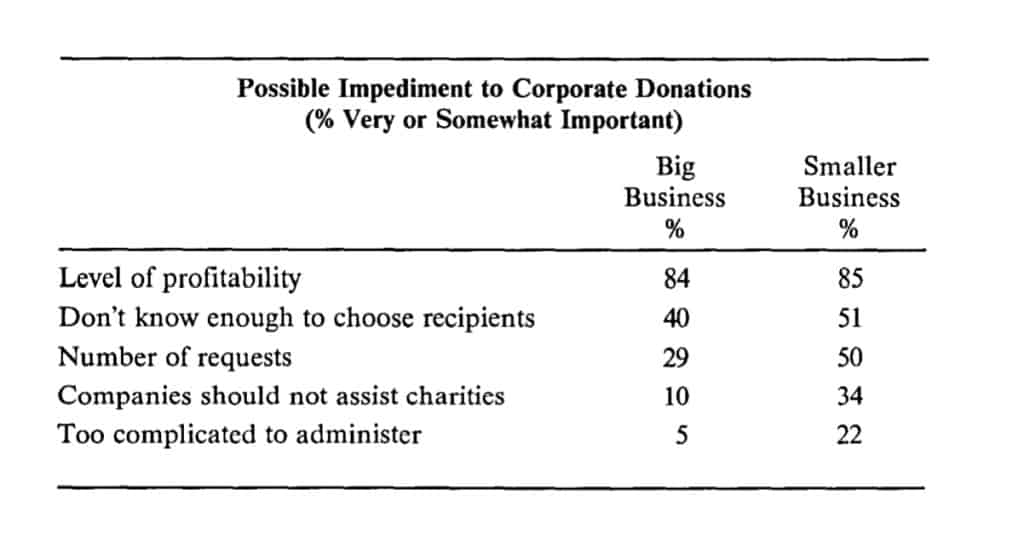

– level of profitability is the major impediment to giving

– smaller companies are less supportive of giving and more concerned about the administration of donations.

Increasing Corporate Giving —IMAGINE

What can be done to increase corporate philanthropy? The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy has recently launched a five-year public- and corporate-awareness program called IMAGINE. [See also {1989), 8 Philanthrop. No. 1, pp. 3-30.] The corporate part of the program has two goals for companies:

– every company having a policy of giving at least one per cent of pre-tax profit (based on the average of the three preceeding years, excluding non-recurring items and foreign operations); and

– every company encouraging its employees to increase their personal donations and involvement in charitable organizations of their own choice.

Clearly, Canadian corporations need some standard against which to measure their donations. After considerable deliberation, IMAGINE settled on one per cent of pre-tax profits as the magic number because it is realistic to relate donations to profits. (To smooth out industry cycles our formula uses the previous three years as base. We also exclude non-recurring items and foreign operations.)

One per cent is clearly an attainable target. In 1986, one out of every seven of Canada’s larger corporations donated one per cent or more of its pre-tax profits to charity. One per cent is also a good round number that’s easy to calculate and easy to communicate and, finally, one per cent is more than most companies give currently so it represents a real increase in the amount of money that would be going to worthy causes.

Increasing the level of contributions from those who are already giving is just one part of our task. We also need to change the attitude and behaviour of those companies which currently give little or nothing. This is clearly a situation where the best way to lead is by example, so an important part of our campaign strategy is to ask companies to let us know when they have adopted a policy of giving at least one per cent and then to allow us to use their names to encourage others.

To gain public recognition for this generosity, IMAGINE will grant the use of its registered designation “a caring company”; will advertise the names of the committed companies nationally; and is arranging a recognition banquet with wide promotion and publicity.

Obviously, this recognition of “caring companies” has two goals: credit for those who deserve it, and a message to the undeserving that they are increasingly out-of-step in not contributing their fair share.

The second goal of our corporate program is to see more companies actively encouraging (and providing opportunities for) their employees to increase their charitable giving and volunteer work.

One priority is the encouragement of regular giving by means of systems such as payroll deduction for charitable gifts. It’s disappointing that so few of the smaller companies have such systems when they have proven to be so successful in raising charitable support. Using company funds to match employees’ giving or support their volunteer work is another successful idea that is common and will be encouraged.

When companies encourage their employees to give personal time to volunteer service, everyone wins! It is an enriching and broadening experience for the volunteer and provides the corporate experience and expertise which are critical to the direction and effective operation of charitable organizations. In addition, there are real long-term benefits for any corporation which invests some of its managerial resources in the solution of the many social problems which affect everyone in the community or society as a whole.

Achieving the one-per-cent giving target for corporate donations is an exciting and impressive prospect. By 1993 Canadian charitable organizations stand to become the beneficiaries of more than 300 million dollars in cumulative increased donations.

ALLAN ARLETT

President and Chief Executive Officer, The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy