In 1914, a lawyer banker by the name of Frederick Harris Goff was responsible for creating a new kind of trust, the Cleveland Foundation. He envisaged that it would provide an efficient means for a person of good will who achieves success in a community to leave something behind for the community’s benefit… and this indeed has been the case.

In 1921, a Winnipeg banker, W. F. Alloway, wrote a cheque for $100,000 to the Winnipeg Foundation and accompanied it with the following words:

“Since I first set foot in Winnipeg 51 years ago, Winnipeg has been my home and has done more for me than it may ever be in my power to repay. I owe everything to this community and I feel it should receive some benefit from what I have been able to accumulate.”

Since that date, some five hundred trusts from bequests and donations totalling $13,000,000 have been established under the aegis of the Winnipeg Foundation. Grants exceeding $11,000,000 have been made by the Foundation during the same period.

In 1935, in Vancouver, ten people each wrote a cheque for $10,000 to start the Vancouver Foundation which now has assets in excess of $45,000,000.

Objectives of Community Foundations

First of all, what are the objectives of community foundations such as those in Cleveland, Winnipeg or Vancouver? Generally they are broad and result in the support of a wide variety of activities.

The objects of the Winnipeg Foundation provide that funds of the Foundation are to be used to provide for needy men, women and children and in particular for the aged, destitute or helpless; the betterment of under-privileged or delinquent persons; the promotion of educational advancement or scientific research for the increase of human knowledge and the alleviation of human suffering; the promotion of the cultural aspects of life in the community; and for any other charitable, educational or cultural purpose that, in the opinion of the board, contributes to the mental, moral and physical improvement of the inhabitants of Winnipeg and its surrounding area.

The Vancouver Foundation has similar objectives and it is likely that the objects of all community trusts are much the same. They can be characterized as follows:

1. Funds are derived from contributions by many donors.

2. Grant programs primarily benefit a particular region or locality.

3

3. Activities are regularly reported to the public.

4. The governing board reflects and, in a broad sense, is representative of the varied elements that make up the community it serves.

5. The use of contributed funds may be altered if purposes designated by donors become impracticable.

Legal Form

The Winnipeg Foundation was incorporated under its own Act in 1921. The Act outlines the responsibilities of the trust and its powers, including management, investment and areas of responsibility and accountability. It has been amended on a few occasions since in order to bring it up to date. Other community trusts have used the Winnipeg Act as a model for their own.

The original Cleveland Foundation established a “trust” which had a single bank as trustee with investment powers but no powers with respect to distribution. Subsequent events saw the creation of multiple bank trusts and, in all trust forms, the banks’ resolution establishing the foundation specified how members of the distribution committee were to be appointed.

In this article we shall examine the various characteristics of a community foundation in detail to see what happens in practice. In Canada, the corporate form seems to be the method that works best and for the purposes of this article will be the one described.

Governing Body

The advisory boards or boards of directors of the community foundations are responsible for the operation of the funds. Their activities include the acceptance of gifts, the investment of assets of the funds and supervision of the making of grants. The members of the board are appointed, in the case of the Winnipeg Foundation, by the Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Manitoba, the Chief Justice of Manitoba, the Chief Justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench for Manitoba, the Mayor of the City of Winnipeg and the Registrar-General of Manitoba, or a majority of those in session. There are to be no more than seven or less than five members and each is appointed for a term of not less than two years or more than five. In practice, the Winnipeg Foundation has a board of seven, six of whom are appointed for terms of four years with the terms rotated in such a way that appointments are made every second year. The mayor of the City of Winnipeg is an ex-officio member of the board. In Vancouver, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia is appointed in the statute and appointments are also made by such groups as the Vancouver Board of Trade, the Vancouver Bar Association, the Vancouver Life Manager’s Association, Pacific Sub-Section, the United Way of Greater Vancouver and by members appointed previously.

In the United States, trustees are often nominated by their custodian banks. In every jurisdiction the boards are intended to be representative of the community which they serve.

The Cleveland Foundation enjoys a reputation of having a governing body that not only represents the community, but reflects it as well. “Their meetings looklike a microcosm of the city itself”, said one grant recipient who had been invited to discuss a proposal. “I thought I was going to make a presentation to a bunch of bank presidents, but when I got in there I found rich and poor, men and women, ethnic representatives and special interest people all talking at once, pointing their fingers at each other and really communicating.”

In a small or new foundation, community representation is difficult to achieve, but with an open-distribution committee system, and a sensitive staff, communication of the real needs of a community to the board can happen.

The board should represent to the potential donor an aura of financial stability, integrity and peer-group motivation, while, on the other hand, it should represent to the grant seeker and the community at large an openness and availability which will indicate that the institution is really part of the action. Some foundations limit board membership for a particular individual to a maximum period of time, usually five to ten years.

Administration

In newly formed foundations, it is likely that all functions will be voluntary, but, as the responsibility grows, permanent staff must be added. This is usually deferred as long as possible because of the cost burden and the general unwillingness to have the income available for grants reduced by high cost.

Some foundations have been assisted by local companies who are willing to pay some of the current expenses required to provide the fund with the professional management its nature demands.

In the case of the Winnipeg Foundation, Mr. Alloway designated in his will that the income from his fund was to be used to pay the administrative costs of the foundation, thus taking the burden off the gifts of future donors. His bequest and his other gifts had a value in excess of $1,000,000 when he died in 1930. In 1927 he wrote a memorandum which was in fact a job description of the Executive-Director long before such a position was filled. His perception was extraordinary as can be seen in his words:

“The desirability of a paid official of the foundation, one of whose duties it will be to keep in touch with the manner in which the trust companies are investing the money of estates.

The importance of having a paid official who would be constantly on the alert to suggest the necessary steps to increase the income is essential.

The effect of having an active officer would bring the purposes of the foundation before the public.”

Such official might also make a study of the various charitable institutions, both those now in existence and those whi-::h it might be desirable to bring into existence. Another very important duty of a paid official would be to contact well-to-do citizens personally for the purpose of inducing them to assist in building up the foundation.

There are no easy answers to the community representation question, and community foundation staff struggle with this problem constantly.

Donations and Bequests

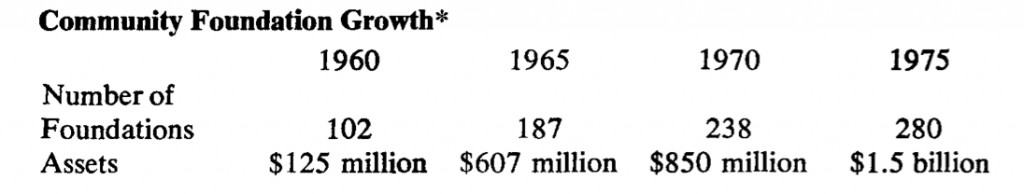

The one consistent theme of all community trusts is that they all expect to grow in the forseeable future. How do they grow?

Individuals or corporations may make donations for which they receive a receipt suitable for tax purposes. Individuals can name the foundation as a beneficiary under the terms of their wills and these bequests can take many forms:

1. Bequest of a specific amount.

2. Bequest of a specific percentage of the estate.

3. Bequest of the residue of the estate.

4. Bequest of the residue subject to life income interest with or without access to capital.

5. Bequest for the general purposes of the foundation.

6. Bequest for designated purposes of the foundation, e.g.,education, youth, etc.

7. Bequest for a designated charity or charities.

8. Bequest for payment of income- most bequests suggest that only income from the trust be granted.

9. Bequest for payments of income and capital- in some cases capital can be entirely used up—in others, if capital is expended it must be replaced by income until the capital is rebuilt to the original level.

Community foundations often act on behalf of other organizations and become the custodian of their endowment funds. For example the Winnipeg Foundation holds trusts on behalf of a number of agencies in the Winnipeg area and pays over the income annually to these agencies. These trusts include the Manitoba Heart Foundation, the Canadian Arthritis and Rheumatism Society, the Canadian Paraplegic Association, the Winnipeg Symphony and others.

What are the advantages of this practice? In taking over responsibility for managing an agency’s funds, the foundation gives stability, particularly to smaller agencies and enables them to concentrate on the thing they do best- i.e., to provide a particular service. There are economies of scale, and full-time management should enable investment returns to be higher.

The great bulk of new money comes from bequests and the largest percentage of the trusts are not designated in any way. What is meant by this is that the disposition of the income generated by this kind of trust is entirely at the discretion of the board. There are, however, a number of trusts where there is a designation of an area of interest—e.g., the assistance of older people—and, in such cases, it is simply a matter of ensuring that, when grants are made for this purpose, funds are withdrawn from the appropriate trust.

Most of the designated trusts are in favour of specific agencies and, in these cases, it is simply a matter of turning the income over to the institution in question on a regular, usually annual, basis.

Why, you might ask, does the individual not simply bequeath the fund directly to the agency itself? The reason surely lies in the fact that recent years have demonstrated that we are in a rapidly changing society and that what may be a need today will not be one tomorrow.

There are many stories told of trusts established for particular needs that have changed or have become obsolete. For example, one trust was established by an English tobacconist who stipulated that after his death his rents should be used to purchase snuff for old women residing in the parish. Bequests have been made to establish funds to make loans to “respectable apprentices” and these funds were still in existence long after apprentices had disappeared. Another fund was established to protect a stream that was Philadelphia’s water supply in colonial times. The stream disappeared as the city grew.

This problem was discussed in a book of speeches by Sir Arthur Hobhouse published in London in 1880 and entitled “The Dead Hand”. A quote from this book is as follows:

“The grip of the dead hand shall be shaken off absolutely and finally; in other words … there shall always be a living and reasonable owner of property, to manage it according to the wants of mankind.”

One of the major factors that leads to the creation of the community foundation concept is the legal doctrine of cy pres. Literally meaning “as near as”, the cy pres doctrine has long been applied by the courts to amend a trust whose originally specified purpose was impossible to accomplish. The community foundations have made the concept of cy pres an integral part of their governing documents. For example, an excerpt from the Act of Incorporation of the Winnipeg Foundation states:

“The board shall, however, in deciding the manner in which the said income shall be used or applied, respect and be governed by any wish or wishes that may be expressed by the donor in the instrument creating any trust or effectuating any gift to the foundation, provided that if in the course of time and after the death of such donor, conditions shall arise whereby in the opinion of the board a departure from such wish or wishes would further the true intent of this Act, the board shall have the power in its absolute discretion to make such departure to the extent necessary to further such true intent and purpose.”

*Council on Foundations

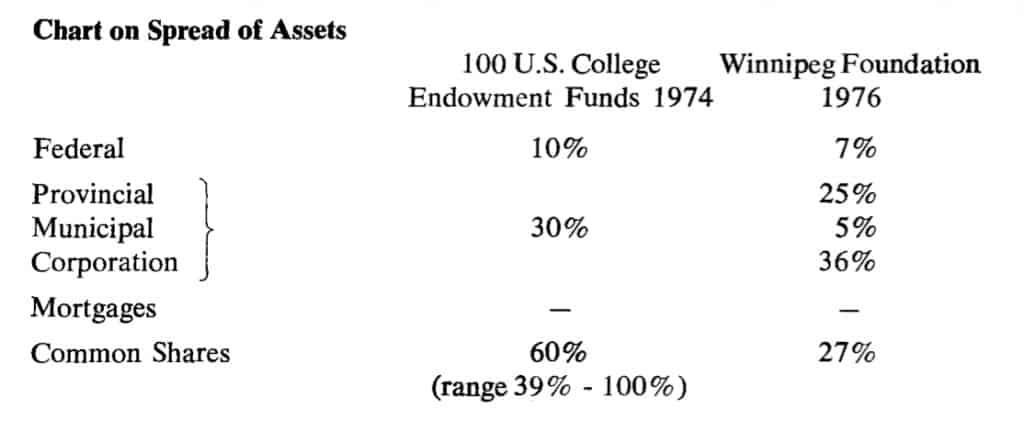

Investment of the Fund The responsibility for the investment of the fund lies with the board if the foundation is organized in a corporate form. It rests with the bank or trust company if it is organized as a single or multiple bank trust.

If the board is responsible, then it must decide how the fund is to be invested. The possibilities are:

1. To set up an investment committee of the board and delegate the responsibility to that body.

2. To give the investment management to the various custodian trust companies or banks and have them report regularly on their results.

3. To hire an investment counsel to manage the fund on an adviwry or discretionary basis.

4. A combination of 1, 2 and 3.

Some portion of the investment function of the board might advantageously be delegated to outside specialists. For example, mortgages might be handled on a pooled-fund basis until the fund is big enough to develop its own diversification. However the decision really depends upon whether the board and management have the expertise to invest the capital fund professionally. It appears that in the United States of America nine out of ten community trusts use their bank trustees for investment purposes.

The critical point, however, is that there must be a clear separation of the physical assets from the operation of the fund itself in order to assure the potential donor that the assets are safely held.

Another important consideration* (*See Editorial page 2) is, of course, the proposed new law governing foundations which is expected to require an earning return of 5% on assets and a minimum payout rate of 90% of earnings, after expenses, each year.

The question of investment policy is an interesting one because, generally speaking, community foundations do not make grants out of capital except in emergencies and, therefore, the only way to profit from holdings in common shares is either by an increase in dividends or by liquidation of a low-yield holding which has made a capital gain and re-investment of the proceeds in an investment with a higher current yield. However, if the payout rate is 90% of the income and if the trustees are concerned about the income needs of tomorrow, then clearly, with any inflation rate, the purchasing power of the assets must be declining to some degree.

Investment yield will increase as new assets are obtained and invested at higher than historic yield levels and, as issues mature, presumably the proceeds can be re-invested advantageously. The reason for owning common shares is that part of the earning power is constantly being re-invested in the business and it is assumed that this will either increase the dividend flow or will affect the market value of the holding posivitely.

This is a partial acceptance of the total return concept, although, with no ability to compound interest earnings such as can be done by pension funds, it is difficult to trade actively in the bond market taking book losses when necessary to shorten term or improve quality. There is no way to replace such losses other than by making trading profits. The key, therefore, is a balanced management approach and a willingness to invest in new vehicles as they become available—for example, NHA mortgages or R.E.I.T.S. in Canada.

Charles D. Ellis in 1971 in “Institutional Investing” summarized the importance of adopting a comprehensive or systems approach to the financial management of foundations as follows:

“Perhaps the most valuable result of a systems analysis of an institution’s finances will be a clearer focus on the opportunity and need to make endowment capital more productive; to make it catch up to the need for increasing spendable funds; the use of endowment capital not as an insurance reserve, but as the vital capital of the institution; to make the endowment fundamentally progressive and oriented to achievement rather than defensive and passive as has been the case in the past.”

In point of fact, any foundation no matter how small, has to be most interested in the investment aspect of the fund, not only to increase the income with which to make grants, but also as one of the important sales tools to encourage other donations to be made. If it can be demonstrated that the money is not only in safe hands, but in good hands, members of the community will be encouraged to donate.

It was stated earlier that there are a number of ways in which donors may designate their gifts. Obviously the grants made are directly affected by these designations. There are four basic options:

1. Unrestricted Funds This is the type of donation that is most sought after because the decision as to distribution rests with the advisory board or distribution committee. Income from donations whose objects are unrestricted can be used very flexibly as conditions change.

2. Restricted Funds The donor selects a particular area of interest, such as assisting youth or medical research, and leaves the foundation to identify the specific project to be benefited in the area designated.

3. Designated Funds The donor in this case selects a particular agency to receive the grant and the responsibility of the foundation is to make the appropriate payment after assuring itself that the agency is still operating. If it is not, the principle of cy pres will apply and the foundation will be responsible to ensure that the funds are used for a similar purpose.

4. Donor Advised Funds The donor in this case wishes to retain an active interest in the grants made. Generally the donor can only be an “advisor” and, if the gift is irrevocable, clearly the donor will have no legal power to determine who the recipients of grants will be unless such a power is specifically reserved when the gift is made. Sometimes donors nominate a third party to be such an advisor, but again such an advisor does not usually have control of the funds. Generally speaking, most foundations do not seek such funds.

The objectives of community foundations are very broad and, therefore, the number of agencies that may be assisted by grants in any given year can be quite large in number relative to the size of the fund. The problem of establishing priority areas of giving is an extremely difficult one because needs change each year.

According to an article published in the Community Foundation News, although most community funds have staff who will be able to respond to a request for funds, few have formal application forms. Most community foundations would echo the advice given by Martin Paley of the San Francisco Foundation- “Put something in writing, nothing elaborate. Then we’ll meet.” It may well be that this terse comment sums up the nature of a community foundation more than any other. It points out the singular commitment of the foundation to a local area and the ability to meet the agency which needs support face to face.

Estimated Field Preference For Community Foundation Grants Compared to Foundation Grants 1974-1975*

|

Fields |

Community Foundation Grants % |

Total Foundation Grants % |

|

Welfare |

34.3 |

13.7 |

|

Health |

23.8 |

21.8 |

|

Education |

22.4 |

27.2 |

|

Humanities |

10.7 |

10.4 |

|

Sciences |

5.5 |

13.9 |

|

Religion |

2.8 |

2.0 |

|

International |

.5 |

11.0 |

*Council on Foundations

It can be seen that community foundations lean more to social service agencies than private foundations.

There are two general categories of grants: “Supportive-reactive” and “change-oriented”.

The supportive-reactive foundation may be more inclined to make grants for a new roof or a new van, something simple and safe. They are reactive in the sense that they respond only to the proposals and requests presented to them.

Some foundations are active and change-oriented. These may provide training and consultation and budget and management assistance. If they are very active they may encourage existing organizations to expand and modify delivery to meet some community needs not now being served.

The size and duration of the grants may give a clue as to whether the foundation is change-oriented or reactive. Small short-duration grants may indicate a supportive-reactive foundation. Those foundations dedicated to change know that some grants will have to be for a longer period of time than others.

Community foundations seldom have special interests that they will always, or never, fund. If they are really trying to meet the needs of a community, inflexibility is almost impossible.

Internally a foundation board may act as a distribution committee but as the size of the fund grows, then it is likely that a separate distribution committee will be established. Such committees frequently call on other people from the community who can act as specialists in a particular field of interest.

Public Relations

There is a need to consider the public relations of a fund.

First, it is important that the public know about and become familiar with the foundation because there is always a need for additional donations and bequests. Second, from the grant point of view, it is important that the people with need know that there is a possibility of obtaining a grant. They have to know the foundation exists and what it does.

Therefore, it is desirable, as well as legally necessary, to publish an annual report which lists donors, grants made, a statement of assets and income, as well as a statement from the board about the events of the year just completed.

Newspapers are used extensively to discuss new bequests or donations received as well as to advertise recent grants made. Some trusts have done substantial advertising in local newspapers to tell their story. The Columbus Foundation did this and, in addition, used television and radio spots and magazine advertisements. The effect was to generate the largest growth in their thirty year history. Some foundations publish quarterly or semiannually news releases. The Cleveland Foundation is an example.

Whatever the method used, it is clear that the public must be made aware of the institution in their midst if the institution is to continue to grow and to provide a meaningful and worthwhile service. However, any advertising must be tastefully and most carefully done.

The Winnipeg Foundation Today

Where does the Winnipeg Foundation fit in the spectrum today?

The assets have grown from the original $100,000 to an amount in excess of $13,000,000. There are approximately 500 separate accounts ranging in size from the Widow’s Mite, an anonymous gift of three $5.00 gold pieces delivered by messenger in 1924, to the W.F. Alloway Estate Fund of $1,752,927.

Many of the gifts and bequests have a story attached to them and, from time to time, notification is received from many distant places indicating that a gift has been made or will be made in the future. Recently we received a cheque as one of the seven residuary beneficiaries of an estate and discovered upon looking into our files that we had a record of being advised in 1924 that such would be the case.

Frequently bequests come from estates of persons with no relatives. However, it would take a whole article in itself to tell each story. It is enough to say that over the years the Winnipeg Foundation, as a result of the efforts of board members and staff, has developed a sufficient reputation for integrity that many individuals have seen fit to include it in their wills or to make donations to the Foundation during their lives.

The making and direction of grants is one that is constantly changing and, as more of the basic welfare needs have been provided by the public purse, the role of the foundation has changed from filling this gap to more innovative approaches. In the early days of the foundation operating grants were made to group homes for troubled boys and at that time those grants formed a substantial part of the budget of the homes. Health was also high on the list and many agencies in the social welfare field in the Winnipeg area have received grants from the foundation over the years.

To-day the breakdown of grants made is as follows:

|

Services for older people |

8% |

|

Children’s and youth services |

8% |

|

Family and general services |

17% |

|

Medical research, health, nursing |

18% |

|

Advancement of education and social work |

17% |

|

Cultural projects |

12% |

|

Recreation and character building |

14% |

|

Designated religious purposes |

6% |

Inevitably, as a community trust, there will continue to be a broad approach to the grants made, but the Winnipeg Foundation stands ready with risk dollars to try new things and, hopefully, to give such new projects enough time to see if they can succeed. We find also that we are one source of capital funds for many agencies that have nowhere else to turn. Admittedly this is a safe place to make grants, but if a group foster home has a leaky roof or a flooded basement or a van that has had an accident, per diem payments simply do not solve their current problem except at a very high cost.The other area that we see as one of our roles is to ensure that some proportion of our dollars is spent on prevention rather than on the very expensive cure after the damage is done. The main funders in the social welfare scheme, government and the United Way, have their plates so full of “have to do” projects, that there is little money left for prevention.

We consider that every community has needs which are very difficult to fill through the regular funding methods and, therefore, every community can benefit from a community trust which can be attuned to the needs of that particular community and which can stand ready in a very human way to respond quickly and positively to such needs. We believe that, as the fund grows, it is likely that we will take on some projects on a somewhat longer basis.

In essence, we believe that in every community there are people like W. F. Alloway and the many others after him who would wish to leave something of themselves behind. We consider that every community should do what it can to develop a community foundation to meet those needs of the community which are not met by government or local United Way funds and we are delighted to see that there are a number already in existence in Canada ranging from the very well-established Vancouver Foundation with $45,000,000 in assets to the St. John Foundation in New Brunswick which was incorporated in 1976.

The Winnipeg Foundation stands ready to assist any community which wishes to set up a new community foundation for the benefit of that community, as well as of Canada as a whole.*

*This article used the following resource material: Community Foundations by Jack Shakely. Community Foundation News- published by the Council on Foundations. Communities wishing to start new trusts may be interested in A Handbook for Community Foundations: Their Formation, Development and Operation by Eugene C. Struckhofj, which is to be published in the United States in the near future.

Alan G. Howson

Executive-Director, The Winnipeg Foundation.