THE PUBLIC TRUSTEE OF ONTARIO

Presented for public comment in conjunction with the Public Trustee’s address “Administrative Considerations in Charities Law. A Viewpoint of the Public Trustee” at the Canadian Bar Association-Ontario’s Continuing Legal Education program Charities and the Tax Man and More held October 16, 1990 in Toronto. The submissions were written by Eric Moore, Director, Charities Division, Office of the Public Trustee, with the assistance of the Charities Division’s professional staff.

Definition of “Charity”

“Charity” is a word of precise and technical legal meaning (National Anti-Vivisection Society v.l.R. Commrs., [1948] AC. 31 at 41) or, to put it another way, every purpose either is or is not legally charitable although the reasons why may not be readily apparent (nor, we might add, easily and convincingly explained to anyone not familiar with the technical and less than coherent case law).

Problems with the Current Meaning

We perceive tremendous confusion in the minds of members of the public, the legal and accounting professions and government as to what constitute charitable purposes. The popular meaning of the term does not accord with the legal. Technical distinctions (e.g., between “charitable” and “not-for-profit”, “benevolent” and “philanthropic”) are not understood. Public confusion is compounded by the fact that “charity” and “charitable” are legally used or applied in specialized senses (e.g., in the Income Tax Act (Canada) and in the licensing of charitable gaming) not wholly consistent with their meanings under the general law.

Defining “Charity”

We think that better defining “charitable purposes” would be most desirable. We have been driven to conclude, however, that a definition that embraced all currently recognized charitable purposes-and we doubt such a definition is possible-would carry with it a real danger of “freezing” evolution of the concept. while a “definition” providing scope for development would add little of the required precision.

A Registration System to Respond to Practical Problems with the Current Meaning

Although much of the conceptual confusion surrounding the meaning of “charitable” perhaps cannot be dispelled, the practical results of that confusion (e.g., non-charitable organizations and appeals passing themselves off as charitable, bona fide charities being denied benefits to which they are entitled and non-charitable organizations obtaining privileges to which charities alone are entitled) can be addressed by a scheme of registration with conclusive effect as to charitable status.

Including Certain Types of Organizations Within Charity

The Ontario Law Reform Commission has raised with us the issue of the charitable status of amateur athletic and sports organizations, interest rights and advocacy organizations and others. We have to point out that none of these types of organization per se is charitable or non-charitable under existing law. Amateur athletic organizations as a group could include: an exclusive ski or racquet club (which we do not think would be charitable) Participaction and Wheelchair Sports for the Disabled (which could be charitable if they desired that status) and a sandlot softball league (which might or might not be charitable, depending upon the purpose for which it was conducted and the group of participants). Similarly, interest rights and advocacy groups could include: business associations, a neighbourhood association fighting the establishment of a group home, environmental watchdog organizations and others.

The sine qua non of charity in its legal sense is benefit to the general public, although that is not sufficient: not every purpose that is of benefit to the general public-and almost every lawful purpose arguably has public benefit-is charitable. In addition, an organization, to be a charity, must be constituted wholly and exclusively for charitable purposes.

Although certain examples of the above general types of organization can be charitable, others involve significant self-interest or benefit that cannot be characterized as being for the general public and therefore do not appear to be charitable under current law. If it is concluded that such organizations ought to be recognized as charitable because the general public benefit they confer outweighs the self-interest, we think that recognition can be achieved only by legislation. Obviously, the same charitable recognition would be sought by many other mixed-purpose organizations outside the general types referred to above.

Forms of Charitable Organizations

The forms in which charities carry on their charitable undertakings has become an issue because of concern that form may affect or, more specifically, frustrate the applicability of trust law to the charity’s property.

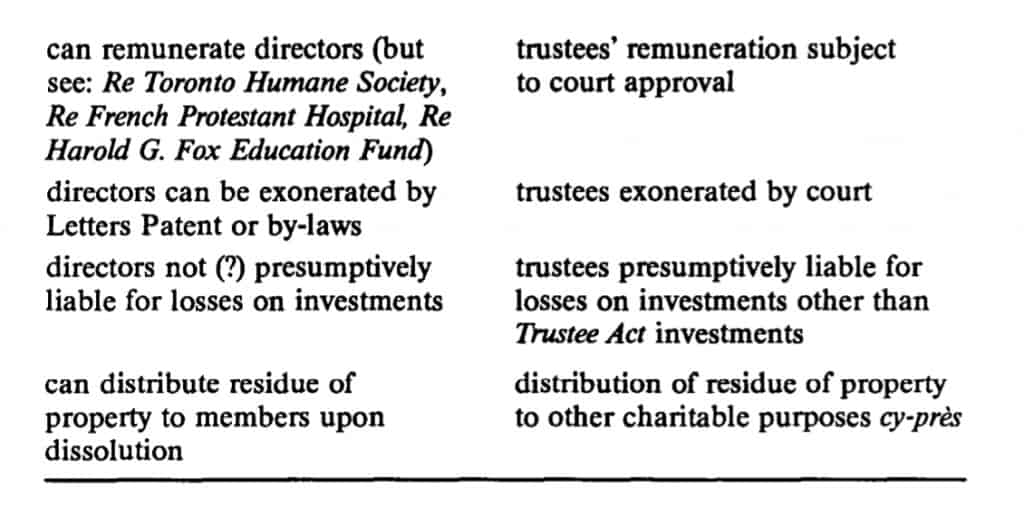

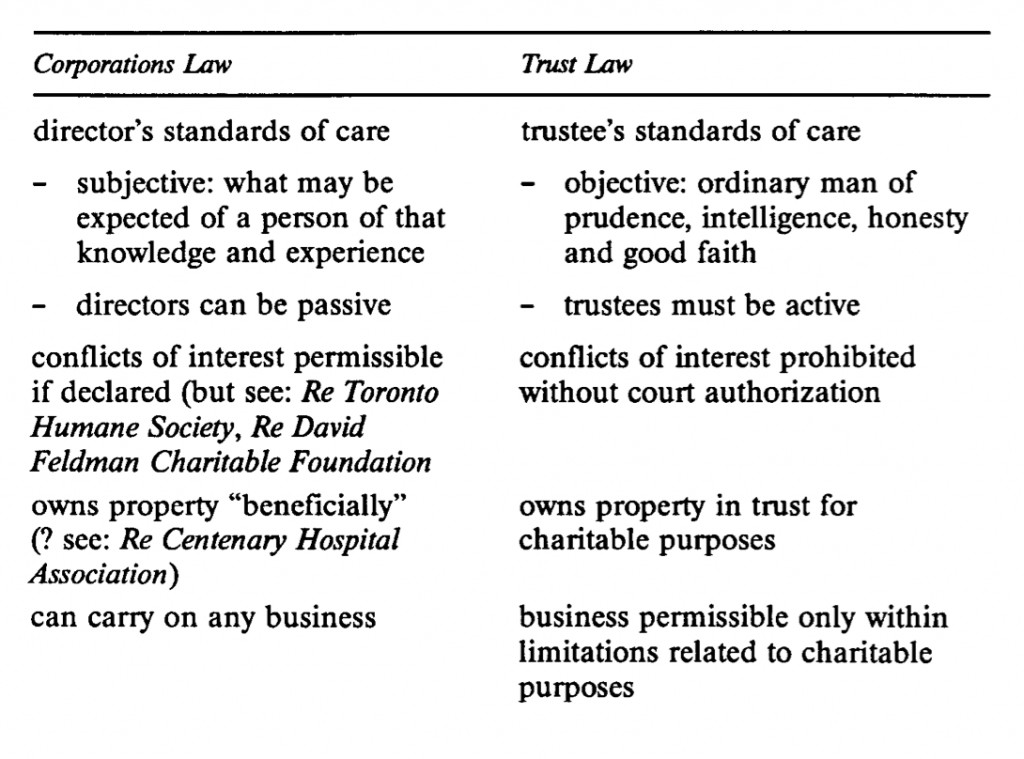

The Incorporated Charity-A Comparison with the Charitable Trust The form of organization in which this issue can most clearly be seen and contrasted with trust law is the charity incorporated under the Corporations Act (Ontario). That the safeguards against abuse provided by the Corporations Act (Ontario) are inadequate for charities law purposes has been judicially recognized (Re Public Trustee and Toronto Humane Society eta/. (1987), 60 O.R. (2d) 236 (H.C.)). A comparison of corporations law with trust law reveals differences of fundamental significance:

Organizational Law to Dictate Charities Law?

We think it undesirable in the extreme that the propriety of the administration and management of charitable property (as distinct from any other issues) and the accountability therefor should be determined by the form in which a charity is organized. The special privileges that charities historically have enjoyed (cy-pres, perpetuity, etc.) are most easily understood by regarding the “charity” as being the body of property held for the charitable purposes rather than the organizational form in which that property may, from time to time, be administered. To permit the organizational form of a charity to determine the propriety of the administration and management of its property and the accountability therefor is, in effect, to permit the organizational laws of Ontario and other jurisdictions (which may not even have been intended to address charities issues) to dictate the Ontario charities law applicable to charities organized under those laws and operating in Ontario.

We think that there ought to be a single regime applicable to the administration and management of charitable property (as distinct from organizational and other issues) rather than a multiplicity depending only upon how charities may organize themselves. We think also that the law of charitable trusts ought to apply to the administration and management of charitable property regardless of the form in which a charity may be organized. The considerations that have led the courts to impose the obligations of trustees upon those holding property for charitable purposes are just as compelling if a charity is organized otherwise than as a trust.

Relevance of Form of Organization to Charities Law

The form of organization of a charity ought to be relevant to charities law issues only for the purposes of determining the powers that the charity may exercise (relevant to the issue of ultra vires which is preliminary to the charities law issue of the propriety of those powers being exercised in any particular circumstance) and for identifying those individuals who legally are responsible for the administration and management of the charity’s property.

Desirability of Charities’ Freedom of Organization

We think that, subject to what has been said above, charities ought to have perfect freedom to organize themselves in any form that they think best in order to carry out their charitable purposes. Differing organizational structures and their comparative advantages and disadvantages-informality of establishing a trust as opposed to the formality and expense of incorporation and maintenance of corporate status; ability to incorporate a charity without the trust’s requirement of a settlement of property; flexibility of internal governance offered by the trust as opposed to the statutorily prescribed but ready-made scheme of the corporation; the personal liability of a trustee as opposed to the limited liability of directors and members of an incorporated charity to its creditors; trustees’ practical difficulties in owning, dealing with, and conveying real property as opposed to the ease in doing so enjoyed by an incorporated charity, among other differences-ought to be available to charities to provide flexibility of organization and operation.

Reconciliation of Charities Law with Organizational Law

We do not see freedom of organization of charities as being irreconcilable with the application of trust law to charitable organizations’ property. We think that this can be accomplished by legislation providing that the property of a charity, regardless of how the charity may be organized, is trust property held for the charity’s purposes; and that those individuals who are responsible for the administration and management of a charity’s property are accountable therefor as if trustees.

In our view, Such legislation would be consistent with judicial decisions which have attempted to reconcile organizational law with the law of trusts by applying trust-law standards and affixing responsibility for the proper administration and management of charities’ property to those individuals who, under the charities’ organizational law, are responsible for the administration and management of that property (Re David Feldman Charitable Foundation (1987), 58 O.R. (2d) 626 (Surr. Ct.), Re

Faith Haven Bible Training Centre (1988), 29 E.T.R. 198 (Ont. Surr. Ct.), In re French Protestant Hospital, [1951] Ch. 567, Harold G. Fox Education Fund v. Public Trustee (1989), 69 O.R. (2d) 742 (H.C.), RePublic Trustee and Toronto Humane Society et al. (1987), 60 O.R. (2d) 236 (H.C.)). Further, it would not represent some unprecedented distortion of organizational laws. The Legislature has seen fit in many instances to attribute to directors of corporations, for example, responsibility and liability for matters that, from the viewpoint of corporations law, are the corporation’s alone, for instance: liability for the corporation’s employees’ wages, corporate compliance with environmental protection standards, corporate collection and remittance of income taxes and Unemployment Insurance and Canada Pension Plan premiums, the accuracy of the corporation’s Offering Memorandum, and professional negligence in the case of professional corporations.

Constitutional Law Considerations

We think such legislation, being directed only at organizations qua charities and at individuals responsible for the direction and control of charitable organizations’ property, can be constitutionally justified as being a proper exercise of the Province’s jurisdiction over “charities” under Head 7 of Section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 and applicable also to charities organized under the laws of Canada (Great West Saddlery Co. v. The King, [1921] 2 AC. 91, Lymburn v. Mayland, [1932] AC. 318, Canadian Indemnity Co. v. A.G. B.C. (1976), 73 D.L.R. (3d) 11 (S.C.C.), A.G. Que. v. Kellogg’s Co. of Canada, [1978] 2 S.C.R. 211, Multiple Access Ltd. v. McCutcheon (1982), 138 D.L.R. (3d) 1 (S.C.C.))

Charities’ Accountability

We believe that those responsible for administering charitable property ought to be accountable to the receiving and benefitting public and to government for the proper performance of that responsibility. Society as a whole benefits from a viable, credible and accountable charitable sector and can properly be concerned to sustain it.

The Receiving and Donating Public

A sine qua non of every charitable undertaking is that it confer a benefit on the general public. Most members of the public also donate time and property to charity. The public, as both beneficiary and donor, therefore has an interest both in the charitable sector as a whole and in the proper administration and management of every charitable organization and all charitable property. Charitable property, in our view, has to be regarded as being in the public rather than the private domain, even if it is not strictly speaking public property.

Government

Government has its own distinct interest in the proper operation of charities. Many thousands of charities receive funding for their charitable purposes from all levels of government. Charities also enjoy governmental subsidy of their operations through exemption from or reduced liability for, a wide variety of taxes at all governmental levels and by income tax relief provided to taxpayers by both the federal and provincial governments in respect of charitable donations.

In addition, charities are given numerous non-fiscal legal privileges, such as opportunities to carry on activities that are otherwise generally proscribed (gaming being perhaps the best-known), perpetual existence (contrary to the general law of trusts), and relief from forfeiture and escheat of their property by operation of the cy-pres doctrine.

The Interrelationship of the Roles of the Public and Government in

Supervising Charities

The necessity for governmental supervision of the application of charitable property is inherent in its nature: it is property given for the benefit of the general public and in respect ofwhich property no person legally has any private interest. That the proper application of charitable property involves matters going beyond private interests is the rationale for the courts’ centuries-old recognition of the Crown’s parens patriae standing in charities matters and for legislative intervention as early as the enactment of the Statute of Elizabeth, 1601, which provided for the appointment of commissioners to investigate charities abuses.

Members of the public have no jurisprudentially recognized rights, whether as donors or as beneficiaries, to intervene legally in the administration of charitable property or even obtain information from which abuse might be detected. In any event, in most instances members of the public have insufficient financial interests and resources to undertake personal legal intervention.

Non-governmental, especially self-regulatory, efforts to supervise the charitable sector are to be applauded, but none has been sufficiently comprehensive or effective to replace governmental supervision. The Better Business Bureau of Metropolitan Toronto, which operates possibly the largest of the non-governmental efforts, reviews the performance of only a few hundred of the 60,000-plus charities in Canada and 35,000-plus charities in Ontario. Review is voluntary, the standards applied do not bear any necessary relation to charities law, and there is no authority to investigate and deal with abuses. The non-governmental sector has been unable to assemble the resources required to carry out a comprehensive and effective system of supervision.

Government can be more effective than members of the public and non-governmental agencies in supervising the charitable sector because it can allocate the resources and legal authority required for that purpose and because it can clearly represent the general public interest in charitable property. Government’s ability to detect abuse on its own must inevitably be limited unless it is to exercise rights of control and day-to-day intervention in charities’ operations that we think are in most instances unnecessary and undesirable generally, as stultifying of the charitable sector’s initiative and innovation.

Members of the public have been of great assistance to our Office by detecting apparent abuses or other sources of concern with the operations of a charity through their opportunities to observe actual operations and notwithstanding limited access to other information about the charity. We believe that members of the public have a critical role to play in conjunction with government in supervising the application of charitable property and that this role ought to be strengthened.

Strengthening the Public’s Role

We believe that members of the public ought to have the right to obtain or inspect prescribed information about charitable organizations. We also do not think that members of the public should be limited to addressing complaints to government Accordingly, we think that members of the public ought to be able to obtain from the courts, orders requiring government to investigate the administration and management of charitable property, such as is currently provided for under sections 6 and 6d of the Charities Accounting Act.

Government’s Rights to Information

We think that retention of the notification requirements of section 1 of the Charities Accounting Act is essential for government to be able to carry out its supervisory function and that a system of graduated regular reporting to government as to the administration of charitable property and as to how a charitable organization is effecting its charitable purposes is justifiable in view of the public nature of, and interests in, that property. We also think that, in addition to being able to require production of information beyond that included in regular reporting (as is currently provided for under section 2 of the Charities Accounting Act) government ought to be able to examine on-site the records of those administering charitable property to investigate abuses and assist in preventing them.

Licensing of Public Solicitation of Donations

We believe that there is need for a requirement that those conducting public solicitations of donations for charities or for charitable purposes be licensed. Substantially all of the deliberate abuses (as opposed to those resulting only from ignorance or incompetence) that we have seen have arisen in connection with fund raising and, in particular, solicitations of donations. Public solicitations offer unique opportunities to abuse specific charities, the charitable sector as a whole, and the donating and receiving public.

We do not think that a licensing requirement necessarily must inhibit initiative and spontaneity of public solicitations of donations. A licence might be required to be obtained within 10 days of the commencement of a first public solicitation and a licence required at the commencement of a second or subsequent public solicitation. Licences ought to be refused, suspended, or revoked (subject to review in the courts) where there exist reasonable grounds for believing that the applicant or licensee would fail, or be unable, fully and properly to account for all donations or that substantially all of the donations would not be received by the charity or applied to the charitable purposes for which they were solicited.

Accountable to Which Government Authority?

It has recently been judicially decided (Re Centenary Hospital Association and Public Trustee (1989), 69 O.R. (2d) 1 (H.C.)) that the Public Trustee has no standing in relation to property that public hospitals have received for their general, as distinct from any special, purposes. Apparently the Minister of Health, acting under the provisions of the Public Hospitals Act, is responsible for supervising public hospitals’ compliance with charities law in respect of property they receive for their general purposes.

Although we have no concern with the jurisdictional aspects of this decision, provided that it is not subsequently interpreted as meaning that hospitals’ general property can be dealt with in derogation of trust law, we are concerned as to the inevitable uncertainty it has created as to the Public Trustee’s authority in relation to the thousands of charitable organizations large and small that are recipients of government funding and subject to varying degrees of governmental control. We think that legislation should specifically identify those charities that are to be exempt from the supervision of the Public Trustee or his successor in charities law matters and identify who is responsible for supervising those charities’ compliance.

Accountable for What Matters and Onus

“Charity” is a fiscally, legally and societally privileged status. We believe that those claiming charitable status ought to bear the onus of establishing entitlement We believe also that those who are responsible for the administration and management of charitable property ought to bear the onus of accountability for all aspects of that responsibility and also for demonstrating how the property’s charitable purposes are being effected. They are, or ought to be, privy to the reasons justifying their administration and management and are best able to adduce relevant evidence. The public and government, on the other hand, usually can only detect seeming problems in all but patent cases of abuse.

Charities’ Activities And Property

General

We do not understand there to be any controversy with respect to charities undertaking any otherwise lawful activity (except, perhaps, political activity) that directly achieves a charitable object.

There is, however, another category of activities which do not themselves directly achieve a charitable object but in which, it has been felt, charities might engage, within some vague and imprecisely defined limits. It is with this category of activities that we perceive there to be controversy. These activities have sometimes been identified as being “ancillary and incidental” to charitable objects. We understand the adjectival phrase in quotes to convey that these activities assist in achieving a charitable object and are somehow subordinate.

It appears to us that the controversy surrounding this category of activities reflects uncertainty caused by the courts’ failure to enunciate meaningful guidelines as to the connection required between activities and a charity’s objects in order for application and risk of charitable property on such activities to be acceptable. We think that as that connection becomes more and more tenuous the risk of abuse and unacceptable loss of charitable property must increase.

Charities are by no means a coherent group of organizations. They are diverse in purposes, sizes, human and financial resources, maturities and activities. Therefore, we do not believe that any useful purpose would be served by legislating any hard and fast rules with respect to permissible administrative costs, accumulation of wealth, borrowing or deficit financing, or other matters that, in the peculiar circumstances of a particular charity, may be justifiable in relation to the charity’s purposes.

Business Activities

Many of charities’ business activities we have no concern with; they directly achieve the charity’s purposes or are subordinate to, and necessary to, carry out activities that directly do so. We have very grave concerns with business activities (whether conducted substantially by volunteers or not) that cannot be justified on the above grounds, whose sole justification and connection with a charity’s purposes is that the anticipated profits from those business activities are to be applied to the charity’s purposes.

There are four inter-related aspects of charities’ business activities that are of particular concern to us: risk, trustees’ liability, conflict of interest, and objectives, values and ethics. There are other aspects, such as unfair competition and self-perpetuating oligarchic control of businesses, that no doubt are of concern to others but that we think are more properly addressed by those others.

Charities’ property is received for their charitable objects. It is one thing for a charity to risk its property in attempting to carry out its charitable objects; charities do so every day as a matter of course by hiring and dismissing employees, contracting commitments and so on. It is quite another thing for charitable property to be diverted to, and risked on, undertakings whose only connection with the charitable objects is that the undertaking may-the “may” is an important qualification that ought not to be forgotten-produce income to fund the carrying out of the charitable objects.

Very many charities currently are unable to account satisfactorily for the property that they are applying only indirectly to carrying out their charitable objects. In the area of charitable gaming, abuse has become a sufficient problem for regulatory legislation to have been introduced into the Legislature. These factors, we suggest, militate very strongly against any right to carry on for-profit businesses being extended to charities generally, although selective extension may not be objectionable on these grounds.

It appears to us to be implicit in proposals that charities ought to be able to carry out business activities that are unconnected to the charities’ objects except by the application of profit, that charitable trustees are to be exonerated from any liability in connection therewith. This would be a startling departure from the standards of conduct hitherto imposed upon trustees. The only instance of which we are aware in which charitable trustees can claim exoneration from liability as of right is in connection with statutorily authorized trustee investments, investments of minimal risk.

We can think of no better protection for the proper administration and management of charitable property than trustees’ liability. If that liability is felt to be unacceptable, that argues strongly for prohibiting any activities other than those most clearly and closely connected to a charity’s objects. There may be particular types of charities for which the general rule of trustees’ liability may be felt to be inappropriate. We think that such exceptional types of charities ought to be selectively dealt with by legislation rather than by excepting all charities from the general rule.

There is also the issue of conflict of interest We have had occasion during the last two years to review a large number of charities’ business activities and business-activity proposals. In almost every instance in which the business activity was unconnected to the charity’s purposes, except by the application of profit to those purposes, we have found serious, material, real conflicts of interest ofwhich the charitable trustees apparently either have been unconscious or have not appreciated the significance. That this type of business activity should so consistently have involved conflicts of interest has to be of concern as evidencing inadequate sensitivity of charities’ trustees to the issue, questionable viability of these activities if conducted without conflicts of interest, or standards of conduct permissible in business being applied also but inappropriately in a trusteeship context It should be noted that substantially all of the provisions of the Charitable Gifts Act are concerned with the relationships between a charity having a business interest, its trustees and the business, i.e., conflict of interest.

Finally, there is the easily stated, although not easily answered, question of how two such intrinsically different undertakings-the charitable, with an object of general public benefit, and the business, with an object that in a different context would unhesitatingly be identified as private profit-can live together.

Is there not real danger that the objectives, values and ethics of one will influence the other, that the business undertaking will cease to be conducted for the ends of profit that was its justification or (and of more concern to us) that the charitable undertaking will cease to be operated for general public benefit? If charities are to be permitted to operate businesses unconnected to their charitable objects except by application of profits, we think that current charitable property ought to be protected from loss from those activities and that such business activities and the associated risk ofloss be disclosed to future potential donors. We further think that provisions of the Charitable Gifts Act relating to the relations between charities, their trustees and charities’ businesses should be retained.

Political Activities

We do not think that the traditional reason advanced for a blanket prohibition on charities undertaking political activity, ie., that the judges cannot tell whether a change in the law will be for good or bad, is convincing. In any event, the proper question, we suggest, is whether obtaining the legislation will directly achieve a charitable object (in many instances it will not) and, if not, can pursuing the legislation otherwise be justified as being sufficiently connected to the achievement of the charity’s objects. If so, we see no reason why it is objectionable. Obviously, however, the sufficiency of the connection between the political activity and the charitable object is the real issue, as it was for business activities.

Landholding by Charities

As recently as 1982, the Ontario Legislature considered the matter of landholding by charities and by enactment of the Charities Accounting Amendment Act, 1982, S.O. 1982, c. 11, imposed the current restrictions found in sections 6a-6c of the Charities Accounting Act, R.S.O. 1980, c.65. It had occasion to consider this matter again, in 1983, when it enacted technical amendments to these restrictions by passage of the Charities Accounting Amendment Act, 1983, S.O. 1983, c. 61.

We see no reason why charities’ landholdings ought to be subject to restrictions different from those applicable to their other forms of property. Every instance of abuse that we have considered we think can be dealt with under the general law relating to charitable trusts. We think that the legislation that has resulted from the Legislature’s recent consideration of this matter reflects concern that charities ought not to apply their property for other than their charitable purposes, land being merely the form of property in which such abuse may be most visible. That general concern, of which this legislation is but a particular expression, we think ought to be addressed in legislation.

Director’s Remuneration

It is our understanding of the law that there is no prohibition on trustees of charitable property receiving remuneration from the charity; rather, in keeping with trustees’ duty to avoid conflict between their duties to their trust and their self-interest, they must obtain approval of the Court to remunerate themselves in any capacity whatsoever.

We see no reasons why charitable trustees should not be remunerated in proper circumstances nor why charitable trustees should automatically be remunerated. We are of the view, however, that charitable trustees ought not to be permitted to determine whether remuneration properly can be paid. No doubt the necessity of obtaining the Court’s approval can be burdensome. We think that the governmental agency supervising the charitable sector might be given the authority to approve remuneration in accordance with the principles enunciated by the courts in order to relieve against this burden.

Scheme-making and Cy-Pres Powers

Under its scheme-making powers, the court can order a scheme for the administration and management of property for charitable purposes where the administration and management have either not been provided for or are incomplete. The court cannot, however, change an existing scheme. Similarly, although under its cy-pres powers the court can order the alternative application of property for charitable purposes, it can do so only where the original trust has become impossible or impracticable to carry out. The court cannot exercise these powers where, for example, a scheme of administration and management of a charitable trust is unnecessarily restricted or where a specific purpose confers little benefit on the general public but might be amended for greater benefit. We think these powers ought to be continued and enlarged to allow for variation on grounds of efficiency and utility, similarly to the provisions enacted in the English Charities Act, 1960.

A New Supervisory System

Adoption of the English Model

We have already advised the Ontario Law Reform Commission of our attraction to adoption of a supervisory system modelled after the English Charities Act, 1960 together with the amendments thereto proposed in the United Kingdom Parliamentary Paper Charities: A Framework for the Future (Cm 694) (London: H.M.S.O. 1989). We believe that such a supervisory system incorporates many of the reforms we have considered above and also would clarify and unify the currently fragmented and incomplete standing of the Public Trustee in charities matters; provide conclusive administrative determination of non-contentious matters as an alternative to curial adjudication; provide a currently lacking preventive jurisdiction against abuse; and provide a statutory scheme of public accountability by charities.

Constitution Act, 1867, Section 96

Section 96 of the Constitution Ac1867, as it has been interpreted and applied by the courts, requires that those who exercise jurisdictions akin to those exercised by the Superior and District Courts in 1867 be appointed by the Governor General-in-Council.

Under the English Charities Ac1960, the Charity Commissioners have jurisdiction co-extensive with that of the High Court in certain matters. Although section 96 of the Constitution Ac1867 may appear to bar the granting of such jurisdiction unless the grantee is a federal appointee, we believe that the fact that such jurisdiction is exercisable for non-contentious matters, that it is subject to review by the courts and that, if necessary, jurisdiction over property might be monetarily limited would be sufficient to avoid the constitutional restriction. (Reference reAdoption Act, [1938] S.C.R. 398, Labour Relations Board of Saskatchewan v. John East Iron Works, [1949] A.C. 134, Reference re Residential Tenancies Act,

1979, [1981] 1 S.C.R. 714).

The Supervisory Authority

Constitution

We have no submissions to make as to whether the Public Trustee ought to remain the supervisory authority in charities law matters, with the enlarged authority we suggest, or whether such enlarged authority ought to be vested in a new supervisory body. We are of the view, however, that a new supervisory body ought not to be part of the ministerial structure of government, but be constituted by appointment by the Lieutenant Governor-in-Council and report to the Legislature.

Charities Advisory Committee

Although charities issues are framed in legal form, many of the component considerations involved in determining those issues involve social rather than legal values. We think that it would be desirable for the Supervising Authority to have available in its decision-making processes the opinion of an advisory committee, composed of representatives of the donating and receiving public, donating organizations, operating charities and others.

A Fully Integrated System of Supe”ision of Charities; A National

Charities Commission

Charities increasingly operate across provincial and national boundaries; are subject to differing substantive and accountability requirements in each jurisdiction in which they operate; and find compliance with these differing requirements increasingly confusing, complex, burdensome and duplicative. In addition, if they have obtained “registered charity” status under the Income Tax Act (Canada) they must also comply with the regulatory requirements under that legislation.

Governmental authorities’ supervisory responsibilities also become increasingly difficult to perform in such a multi-jurisdictional environment.

We think consideration ought to be given to the establishment of a National Charities Commission. Such a National Charities Commission could exercise the supervisory role and be a single authority to which reporting would be made under the laws of each participating province. In addition, the federal government could delegate to the National Charities Commission the authority to administer the provisions of the Income Tax Act (Canada) in respect of “registered charities”.

Such a National Charities Commission would offer the charitable sector the advantages of unified reporting and a single agency with which to deal. For government, it would offer unified, more comprehensive supervision and a reduction in duplicative effort For the public it would offer a single agency to which it could address its concerns. Such a National Charities Commission could also be expected to become a strong force for uniformity of charities law.

APPENDIX A

A Partial List of Statutes Providing Charities’ Tax Exemptions and

Reductions

Assessment Act, R.S.O. 1980, c. 31, as amended Corporations Tax Act, R.S.O. 1980, c. 302, as amended Excise Tax Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. E-15, as amended

Goods and Services Tax Act (Canada Bill C-62, pending before the Senate)

Income Tax Act, RS.C. 1970, c. 1-5, c. 148, as amended

Income Tax Act, RS.O. 1980, c. 213, as amended

Municipal Act, RS.O. 1980, c. 302, as amended

Provincial Land Tax Act, RS.O. 1980, c. 399, as amended

Retail Sales Tax Act, RS.0.1980, c. 454, as amended

APPENDIXB

Statute References

Charitable Gifts Act, RS.O. 1980, c. 63

Charities Accounting Act, RS.O. 1980, c. 65, as amended

Charities Accounting Amendment Act, S.O. 1982, c. 11

Charities Accounting Amendment Act, S.O. 1983, c. 61

Charities Act. 1960 (U.K) 8 & 9 Eliz. II, c. 58, as amended

Constitution Act, 1867 (U.K), 30 & 31 Viet c. 3

Corporations Act, RS.O. 1980, c. 95, as amended

Income Tax Act, RS.C. 1970, c. 1-5, as amended

APPENDIXC

Case References

A.G. Que. v. Kellogg’s Co. of Canada, [1978]2 S.C.R 211

Canadian Indemnity Co. v.A.G. B.C. (1976), 73 D.L.R (3d) 11(S.C.C.)

Re Centenary Hospital Association and Public Trustee (1989), 69 O.R (2d) 1 (H.C.)

Re David Feldman Charitable Foundation (1987), 580 O.R (2d) 626 (Surr. Ct.)

Re Faith Haven Bible Training Centre (1988), 29 E.T.R 198 (Ont. Surr. Ct)

In re French Protestant Hospital, (1951] Ch. 567

Great West Saddlery Co. v. The King, [1921] 2 AC. 91 (P.C.)

Harold G. Fox Education Fund v. Public Trustee (1989), 69 O.R (2d) 742 (H.C.)

Labour Relations Board of Saskatchewan v. John East Iron Works, (1949] AC. 134 (P.C.)

Lymburn v. Mayland, [1932] AC. 318 (P.C.)

Multiple Access Ltd. v. McCutcheon (1982), 138 D.LR (3d) 1 (S.C.C.))

National Anti-Vivisection Society v. LR. Commrs., [1948) AC. 31 (H.L.)

RePublic Trustee and Toronto Humane Society et al. (1987), 60 O.R (2d) 236 (H.C.)

Reference re Residential Tenancies Act, 1979, [1981] 1 S.C.R 714

Reference reAdoption Act, [1938] S.C.R 398