The following is a general overview of some of the income tax considerations affecting charitable donations.1 Since it is an overview, the discussion is not intended as tax advice in respect of any particular charitable-donation or fund-raising technique and charities and prospective donors are urged to obtain specific advice in particular transactions where tax issues may be in question.

“Gifts”

Before considering specific giving techniques, it will be helpful to review the question of what constitutes a gift since, after all, it is gifts, not payments, to charities that are eligible for tax receipts and it is this question that is fundamental to the tax-effectiveness of all payments or transfers to charities.

Provision for the deduction of charitable gifts is found in paragraph l!O(l)(a) of the Income Tax Act (Canada) (the “”Act’). Under that provision a taxpayer may, subject to certain limits, deduct the “aggregate of gifts made” to registered charities or other specifically mentioned entities.2

The question of what constitutes a “gift” is not dealt with in the Act but has been the subject of a number of cases. Further, Revenue Canada has published a number of bulletins and circulars which set out its policies on what constitutes a gift for tax purposes. While case law and departmental guidelines create the framework within which registered charities pursue and receipt gifts, such a framework is not rigid as evidenced by the continued evolution of case law and persistent attempts on the part of many charitable organizations to expand the scope of deductible gifts. However, the danger of attempting to expand the scope of deductible gifts is not only that such attempts may fail but that the framework surrounding deductible gifts may actually contract and become more limiting.

Generally speaking, the courts have defined a deductible gift as a voluntary transfer of property where no advantage of a material character is received in return by the transferor. That the transferor payment be “voluntary” has been taken to mean that the transfer was not made as a result of a contractual obligation (which generally arises where an advantage of a material character is received in return for the transfer). That is, in most cases, in determining whether or not a payment or transfer to a registered charity will be deductible, the key question will be whether or not the transferor received an advantage of a material character in return for the payment or transfer.

A recent high court decision in Canada which considered the meaning of the word “gift” is the case of The Queen v. McBurney.3 In that case, the Federal Court of Appeal held that gifts to a particular religious school which provided religious as well as secular training and which was attended by the children of the donor, derived from the donor’s sense of personal obligation, as a Christian parent, to ensure a Christian education for his children and as such could not be regarded as a “gift” in the ordinary sense of the word.

If responding to what is perceived as a Christian duty leads a gift to be categorized as other than voluntary or as made to secure a “material” benefit such as a Christian education, then many gifts as we now define them may not be “gifts” for tax purposes. Are contributions to a Sunday school attended by the children of the donor “gifts” in the ordinary sense of the word if they derive from a sense of Christian duty to ensure religious education for the donor’s children? Even Revenue Canada accepts such contributions as gifts. Is a contribution to my church, made to help expand the facility which my family regularly uses and attends, a “gift” ifl admit that my contribution derives from a sense of personal obligation as a Christian or to ensure for my family premises within which to worship? I am fairly certain that Revenue Canada would have no problem in recognizing such a contribution as a gift. Would a contribution to a registered Canadian Amateur Athletic Association which trains

children (including one of my own), as competitive swimmers, not be a “gift”if I acknowledge that the contribution was made out of a desire that my child be a world class swimmer or a sense of parental obligation to ensure for my child the physical and competitive environment that I think necessary for his or her upbringing and wellbeing? Revenue Canada has unsuccessfully challenged such contributions in many cases.4

So what, if any, are the broader implications of the McBurney decision? If the case is limited to its facts, as I think it must be, then it speaks only to circumstances where a “material” benefit such as a secular education is being derived. Where instruction turns to a “material” benefit, no gift exists. Ifl pay the Red Cross to teach my child to qualify as a lifeguard, I have contracted for a material benefit. If I contribute funds to a Canadian Amateur Athletic Association in the hope and expectation that my child will become a worldclass swimmer, I have probably made a gift. Distinctions in some cases will obviously be hard to draw.

I should also note that the particular facts of the McBurney case raise another issue, namely, whether or not the portion of a payment relating to the cost of providing religious training, as opposed to secular education, is properly regarded as a deductible gift. It was held, again on the facts of this particular case as I understand them, that the entire “tuition” was a non-deductible payment notwithstanding that it might have been possible to segregate the cost of operating the secular (i.e., material), portion of the school fee from the cost of providing religious instruction. If payments for religious instruction are

indeed “gifts”, could the court not have dirt”cted the matter back to the Minister for a determination of the gift element?

That the court did not do so suggests to me that segregation of a single payment is not a matter of right in law.5 lt is interesting to note, however, that Revenue Canada, as an administrative practice, permits the segregation of tuition payments and allows a deduction to the extent of the cost attributable to religious training.6 Since such treatment appears to be at the discretion of Revenue Canada, it seems necessary to follow Revenue Canada’s guidelines regarding this favoured treatment carefully. If, for some reason (as in the McBurney case), the guidelines are not followed, recourse to the courts to obtain charitable-gift status for a portion of a tuition fee, or for a portion of a contribution some part of which is not attributable to a material benefit received, may not be available. Indeed, the issue of segregating costs, i.e., attributing a portion of payments to a registered charity to the cost of a nondeductible item and a portion to a gift, may have broader implications than following Revenue Canada’s guidelines on school tuition fees for private schools.

Consider again the legal definition of a gift. A payment made pursuant to a contractual obligation, e.g., made for material consideration, is not a “gift” in law. It is also important to understand that the law does not look to the sufficiency of consideration in recognizing a contractual obligation. Ifl promise to transfer my car for $100, then I may have a legal obligation to do so notwithstanding that my car has a value of$10.000. The portion of the value of the property transferred in excess of the nominal consideration is not, in law, a gift. An understanding of this legal principle is particularly important in cases where administrative exceptions to the principle are allowed by Revenue Canada since, in such cases, charities and donors are, as illustrated in the McBurney case, likely to be at Revenue Canada’s mercy. Let us consider some examples:

I. Fund-raising events where the cost or value of admission. food. entertainment. prizes, mementos, etc., is less than the payment:

If the law does not look to the sufficiency of the consideration provided by the charity to the donor. a $500 dinner is just that, even if the dinner has a value of $25.

While Revenue Canada permits recognition of two component parts to the payment in at least some cases such as the value of a dinner versus the gift component, in other cases its position appears less flexible. Attribution of component parts for the purchase of lottery tickets or for mementos received, such as books, is not formally permitted by Revenue Canada and their legal position may be strong notwithstanding their liberal and, perhaps, inconsistent administrative practice in other cases. If charitable receipts are desired in these cases, it may be important to consider effective approaches which, in law, support the intended element of gift. A $500-per-person dinner and lottery event,

complete with live entertainment, should be sold in at least two, if not three, parts: admission and dinner $50, lottery ticket $50 and suggested donation $400. Provided admission and eligibility to win the lottery are permitted even though no donation is made then, in law, the $400 donation is truly a gift.

Administratively, Revenue Canada requires that the admission and lottery portion of the ticket be charged at fair market value. Revenue Canada further considers that the fair market value of a chance to win a lottery is the full amount of the ticket price, i.e., no portion is to be treated as a gift,? In law this position may, arguably, be wrong. Since the law does not look at the sufficiency of consideration in determining contractual obligations, a charity may be required to produce a steak dinner and lottery for $1.00 if the “ticket”so requires. In such case, and in the context of the above example, $499 is a true gift provided I am entitled to attend, eat and win without making the $499 donation. To avoid a variety of problems associated with a successful attack on this legal notion, it is recommended that the charge for any event, or for any material consideration given to a donor, equal at least the charity’s cost of providing same. (Note: If the apportionment format is not as described above, i.e., a suggested but not a required donation, then Revenue Canada’s guidelines for attributing fair market value should be followed, otherwise the entire payment may not constitute a gift in law. Further, it should be noted that it is Revenue Canada’s position that even suggested, as opposed to mandatory, donations accompanied by the chance of a prize are not deductible gifts where donors are “induced” to make the donations because of the prize. I believe Revenue Canada may be on weak ground in regard to this position.)

2. Annuities:

While annuities will be discussed very generally later in this paper they are, in some instances at least, another example of payments for consideration to which a gift element may be attributed only if Revenue Canada’s administrative guidelines are followed.

One last comment on the subject of gifts is that not all donors will require payments to be “gifts” in order for them to be deductible for tax purposes. Payments to charities may constitute outlays incurred to gain or produce income. For example businesses may deduct necessary outlays for cu”ent advertising or promotional benefits where, say, supporters of the charity are clients or potential clients of the business.8 Such deductible outlays are not subject to the limitations discussed below.

Statutory Limitations

The primary limitation regarding charitable donations is that taxpayers cannot deduct more than 20 per cent of their incomes for the year in respect of charitable donations made in that year. Further, a taxpayer has a five-year carry forward of excess (unused) charitable donations.9 Donors can claim as much, within the 20-per-cent limitation, or as little as they choose in respect of a charitable donation in the year with the unused balance being available as a deduction in any of the subsequent five years (in such amounts each year as the taxpayer, again within the 20-per-cent limitation, may choose to claim). This flexibility may be of value to a donor whose income in a particular year is not subject to as high a marginal rate of tax as might be expected in the next year.10

A planning point with respect to the 20-per-cent limit is that corporations are, in law, entities distinct from their shareholders so that an individual might make a personal charitable contribution to which the 20-per-cent limitation would apply and then make a further contribution through his or her corporation which would have a separate 20-per-cent limitation in respect of the corporation’s income.

It is not uncommon for corporations to pay down large bonuses to shareholder employees so as to reduce corporate income to a level which will be subjected to the low corporate tax rate. A corporation making a charitable donation in such circumstances should consider limiting such bonuses so as to ensure that any deducation that it will have for a charitable donation will be a deduction in respect of income subject to a high rate of tax.11 For example, a corporation could pay bonuses to reduce corporate income to $250,000 which would then permit a charitable donation of$50,000, i.e., 20 per cent of the predonation income. In this way the corporation will save the high rate of tax on the $50,000 donation and the shareholder employee will have $50,000 less income to report personally (which in Manitoba will save that shareholder employee tax at top rates of up to 60 per cent12). As stated, the employee shareholder could still make a separate charitable donation subject to a deduction limit of 20 per cent of his income in that year.

In one case,13 unsuccessfully challenged by Revenue Canada, a philanthropic employer declared bonuses for all of his employees and, with their consent (perhaps coerced), paid such bonuses to his favorite charity. The employer took ordinary operating expense deductions for the bonuses and the employees took deductions for the charitable donations. Had the employer not declared bonuses but paid corporate profits to the charity directly, the corporation’s 20-per-cent limitation would no doubt have been exceeded. The court found this was not a sham, allowed the deductions, and seemed to pay no heed to the acknowledged likelihood that the size of the bonuses was directly related to the employee’s generosity to the employer’s favorite charity. While this is an interesting case, I would not recommend it as a precedent to follow.

Another donation plan aimed at avoiding the 20-per-cent limitation rule involves loans to charitable organizations. A loan can be made on a demand basis, interest free, and the charity will have the use of the funds. The “donor” lender has foregone the earning power on the amount of the loan and to that extent has achieved a reduction in what his income would otherwise be in the same way that he would get a reduction in his income by making a charitable donation. This loan technique is not subject to the 20-per-cent limitation rule; indeed the donor can make a donation in addition to the loan with only the donation being subject to the 20-per-cent of income limitation.

It is not uncommon to approach loans through a trust. The trust permits the trustee to hold the proceeds of the loan and simply pay income annually to the charity beneficiary. Since the use of trusts does not involve an incurrence of debt by the charity, charitable foundations, as well as charitable organizations, can be beneficiaries. To ensure that the trust is not subject to income tax, the charity’s entitlement to receive the income in the year that it is earned by the trust, must be absolute. Direct loans through a trust are flexible for the donor in that they can be called or revoked at a future time. Conversely, the notes of the trust can be given or made a bequest to the charity at a future time with a deduction at that time in respect of the amount of such gifts. (Note:It is important to distinguish settlements to trusts from loans to trusts since, in the former case, the income benefit directed to the charity will be attributed back to the settlor for tax purposes unless the capital is irrevocably designated to a specific beneficiary other than the settlor.14 Further, if appreciated capital assets are settled on such trusts, such settlement will trigger a capital gain in the hands of the settlor.15

It should also be noted that there are statutory limitation. For example, gifts to Her Majesty in Right of Canada or Her Majesty in Right of a Province are not subject to it.16 Further, gifts of cultural property that are designated by the Cultural Property Review Board (established under the Cultural Property Export and Import Act of Canada), to be of importance to Canada’s heritage for historic, artistic or other reasons will not be subject to the 20-per-cent limitation provided that they are made to an institution which the Board has designated as an institution entitled to receive such property.17

Deductions Between Spouses

Although technically not permitted under the Act, it should be noted that Revenue Canada, as a matter of administrative practice, allows either spouse to claim charitable donations no matter which spouse makes the donation and no matter which spouse is named on the receipt issued by the charity. In the case of significant donations, where a charitable donation is to be claimed by the spouse of the person named on the receipt (or even split between the spouses), some caution might be prudent since it is only an administrative practice that permits this type of planning. A more cautious approach would be to document gifts between spouses prior to the donation so that the desired taxpayer makes the donation.

Year of Death

A gift in the year of death is deemed to have been made in the immediately preceding year to the extent that it was not deducted in the year in which the donor died. That is, in the year of death a one-year carry back is available.18 Again, the amount deducted in the year of death as against the amount carried back is at the option of the donor(i.e., his executors), but in both cases the 20-per-cent of income limitation applies. Bequests by will are treated the same as, and are indeed deemed to be, gifts made in the year of death19 with the exception that a gift of capital received by a charity under a will is not subject to the disbursement quota rules.20

Gifts-in-Kind

There are a number of general rules that should be kept in mind with respect to gifts-in-kind to charities. Where property is given to a charity, the donor is deemed to have sold the property to the charity for its fair market value. The charity of course may issue a tax receipt for the fair market value of the property donated. If the property is capital propert}’, one half of the donor’s gain on the property will be added to his or her income. Since capital gains are now eligible for a lifetime capital gains exemption of up to $500,0002 this should not result in a tax cost in many cases of a donation of capital property so it will now be easier for donors to make such gifts. If a taxpayer wants to reduce the capital gain triggered on a gift-in-kind, he or she may elect to give the property at a designated value which will determine both the amount of the gain and the amount of the tax receipt that will be issued in respect of the gift.22 Presumably, this election would only be made where the donor had exceeded the 20-percent of income limitation, otherwise the amount of tax saved as a result of the donation would more than offset the amount of tax paid on the resultant capital gain.

The election rule mentioned above applies only to a gift of tangible capital property and does not apply to property that is not capital property or to property that is not tangible. For example, property such as stocks, bonds, etc., is not tangible property and therefore would not qualify. Revenue Canada apparently permits the election only if the property can be used directly by the charity in its activities23 but this apparent restriction has no legislative basis, at least in respect of the donor. Presumably if a charity received a property that it could not “use”, it would sell it and use the proceeds for its charitable activities. If the sale of property is not “direct use by the charity in its activities”, it should at least be considered a related business but in any event the use by the charity should not affect the donor’s entitlement to the election.

The election in respect of tangible capital property applies to bequests as well as to inter vivos gifts so executors should ensure that appropriate designations are made in the deceased’s return for the year of death to avoid any unnecessary gains being triggered or capital gains exemptions being wasted where, but for the election, the amount of the gain would exceed the deceased’s deduction limits. The election is available as a result of a provision in the Act that states that bequests to registered charities are deemed to have been made in the year of death.24 It follows that property bequeathed to a charity is not subject to the normal deemed disposition rules that deem property of the deceased to have been disposed of immediately before death.

A donation of property that is part of the donor’s inventory is unusual since generally no tax benefits accrue but recent changes to the rule relating to gifts from the inventory of artists make it easier forth em to donate from their inventories. The Act now allows artists to value their inventories at any amount between the cost to them and the fair market value when they are making a charitable donation of such inventory.25 An analogy to donations of inventory would be the donation of property which has been fully expensed by the donor. In such cases the amount of the deduction, subject to the 20-per-cent of income limitation, will equal the amount of the income inclusion triggered by the donation. Revenue Canada’s position on expensable property is that no charitable receipt should be given.

As an administrative practice, Revenue Canada does not permit the issuing of charitable receipts for donations of personal effects.26 This policy is a practical one without support in law. The real issue is valuation of items of “minimal value”. If this problem can be solved to a charity’s satisfaction, receipts could well be issued. For example, ifl made a gift of the proceeds of a disposition of personal effects given to a charity’s flea market, a charitable receipt could be issued provided the charity in fact records the actual proceeds received from the sale of the particular goods provided by me.

Gifts to the Crown and gifts of prescribed cultural property are not subject to the 20-per-cent of income limit so that realization at fair market value should not prove onerous.27

It is important that charities use qualified experts to value property for the purpose of issuing receipts for gifts-in-kind since there have been a number of attempts at tax fraud involving inflated values for such property as works of art.

Residual Interest

Bequests (i.e., a provision for a charity in a will) may not be tax-effective since the amount of the tax deduction available at death cannot be known when the will is made and might well be substantially less than the value of the bequest.28 Charities have therefore been encouraged to look for methods whereby a receipt could be given for current tax purposes while permitting, as in the case of a bequest, the donor to retain the benefits of the gifted property during his or her lifetime. It is indeed possible to make gifts which vest in the charity currently but under the terms of which some benefit is retained by the donor. The value to the charity of the vested interest is arguably a gift made in the year such vesting occurs or, put another way, the value of the retained benefit simply operates to reduce the value of the current gift and the amount of the available deduction. A gift subject to donors’ retaining an interest in the gifted property during their lifetimes is a gift of a “residual interest”.

If donors have a capital asset that they wish ultimately to donate to a charity but want to use that asset during their lifetimes, they can make a gift of their residual interest in the property. The charity’s entitlement to the residual

interest in the property is immediate although possession of the property itself will not take place until the death of the donor. In this case only a portion of the present value of the subject property is deductible, i.e., the residual value. Note also that the deemed disposition rules will also apply in respect of the disposition of the residual interest. Revenue Canada permits an apportionment of cost base, for the purposes of determining the gain on the disposition, on the basis of the relative value of the residual interest at the time of the disposition compared to the whole value of the property at that time. It is uncertain whether or not a residual interest in a tangible capital property is itself a tangible capital property for the purposes of the election referred to earlier and it may be advisable to obtain an advance ruling if a donor is relying on the availability of such election. Indeed, rulings on significant residual interest transactions are probably advisable in any event. It would be well to seek advice to ensure that:

1. the entitlement granted to the charity is a gift (poorly drafted documents could exclude classification as a “gift”);

2. the gift of the residual interest vests in a particular year;

3. vesting in that particular year constitutes a gift made in that year(in some cases Revenue Canada has apparently ruled otherwise); and

4. the cost-base apportionment calculation set out in Interpretation Bulletin IT-226 will apply to the transaction using values at the date of the gift.

It has been argued that a loss will occur on the death of the donor of a residual interest since the value of the donor’s life interest in the property immediately before death may reasonably be less that the balance of his or her cost base in the property or may, in some cases at least, be zero. There is certainly nothing stopping an executor from taking this position and such a position should not adversely affect the charity which has only been a party to receipting the gift of the residual interest.

Potentially the simplest method of obtaining a current deduction for a future gift is a gift of a promissory note payable on death. As a gift-in-kind it has a discountable present value. Apparently Revenue Canada has indicated it does not favour this plan.29 If this position is based on a legal position such as one which concludes that no gift is made in the year notwithstanding the charity’s ownership of the note and its interest in the estate of the donor, then such a position might easily be extended to all gifts of residual interests. A better distinction, however, might be that vesting cannot occur unless a specific property, as opposed to an amount of money, vests to the charity. This distinction seems tenable in respect of comparisons with residual interest transactions but ignores the reality that the note is property with a current value at the time ofits transfer. Instead of comparing the gift of a note to a residual-interest transfer one might consider settling cash to a trust with the life-income interest going to the settlor and the capital interest going to the charity on the death of the income beneficiary.

This type of gifting program has some resemblance to a charity-funded annuity program. Other “annuity type” programs might include settlor entitlements to a return of capital over a fixed period. (To avoid income attribution such a plan might be structured as a loan to a trust with principal payments made over a given period.) To ensure an “annuity” for the life of the settlor, a deferred life annuity could be purchased (by the trust) commencing after the principal repayments are made in full. Although some of the complexities and risks of annuity programs are avoided by the use of such quasi annuities, the relative tax benefits of each alternative must be considered as well.

Annuities

Annuity programs grant the annuity purchaser a right to guaranteed payments for life at a predetermined rate based on life expectancy and stated interest rates. The right to guaranteed payments is the consideration for the annuity purchase price but for Revenue Canada’s administrative practice, arguably no gift is being made in law.

If a charity undertakes to go into the annuity business it should do so with considerable caution and in full compliance with Revenue Canada’s guidelines.30

The tax benefits available to annuitants of annuities issued by charitable organizations are described in Interpretation Bulletin IT-111 R, paragraph 3:

Because of a charitable interest in the organization an individual sometimes pays more for the annuity than the total amount expected to be received as annuity payments. In such cases Revenue Canada is prepared to take the view that the excess of the purchase price over the amounts expected to be returned is a gift and the individual is entitled to deduct the amount of the gift to the extent allowed by paragraph 110(1)(a) provided an official receipt is produced in accordance with Part XXXV of the Income Tax Regulations. No portion of any annuity payment is taxable in the hands of the individual in these circumstances.

Where an individual pays more for an annuity than the total amount expected to be received he has actuarially foregone100 per cent of the earning power of the annuity purchase price and at least some of the annuity purchase price itself. In such case it is understandable, although not necessarily legally accurate, that the excess annuity purchase price should be treated as a gift and that the annuity payments should not be taxable when received by the annuitant. Where the annuity purchase price is less than the total amount expected to be received as annuity payments, then the Bulletin, on its face, does not apply, notwithstanding that the annuity payments may amount to something substantially less than what might be taxed not only when received but also, in the case of deferred annuities, on an accrued basis annually or on the third anniversary of the contract. The taxable portion of the annuity, or the taxable

accrued interest benefit, is the interest portion of the receipt or benefit as determined by the interest rate used in the contract applied against the annuity purchase price for the relevant period. While the interest factor for an annuity issued by a charity should be relatively small, the adminstrative and tax rules governing it are complex.

A discussion of the complexity of regulations dealing with charitable organizations issuing annuities could occupy the entire journal. Consider the following examples of issues that would have to be addressed before a charitable organization ventured into the business of issuing annuities:

– Are charities responsible for reporting to annuitants the amounts that must be included in their incomes each year?

– Are charities governed by the Canadian and British Insurance Companies Act and provincial insurance acts which regulate the annuities business?

– Who is responsible if the charity is unable to make payments under an annuity obligation?

– To what extent are reserves required to provide for unfavourable mortality or interest experience and how would such reserves inter-relate with disbursement quotas?

– Will an extensive annuity program constitute a related business?

I have already mentioned that there are quasi-annuity structures available that reduce the complexities and risks associated with a charitable organization’s undertaking an annuities business. Yet another approach is to be a third party to an annuity contract between a donor and a life insurance issuer of annuities. Only the “gift” portion of the annuity purchase price is retained by the charity in this case and, following Revenue Canada’s guidelines, a charitable donation receipt can be issued to the annuitant for the extent of such a gift. A number of financial institutions also offer annuity packages for charities. However such plans are generally structured as trusts and are closer to residual-interest transfers than to true annuities, i.e., the charity is the capital beneficiary of the trust. Although the “gift” can be actuarially determined, whether the charity actually receives a donation will, in some cases, depend on mortality and interest experience.

It should also be noted that a charitable foundation is not allowed to incur debt and, as such, may not itself issue annuities.31

Insurance

A gift of a life insurance policy with a cash surrender value will entitle the donor to a charitable receipt for that cash surrender value.32 A gift of such a policy to a charity will, however, trigger taxable income in the hands of the donor to the extent that the cash surrender value exceeds the donor’s adjusted cost base in the policy (i.e., the taxable income will generally equal untaxed accumulated dividends and interest). The cash surrender value is subject to the charity’s disbursement quota unless the gift is subject to a condition that it be retained for 10 years.33 Where there is no such condition the charity can usually borrow against the cash surrender value if necessary.

Premium payments are charitable donations if the premium amount is given to the charity or the payment is made directly to the insurance company by the donor with the consent of the charity.34

Although I have indicated that a charitable donation only exists on the gift of a policy to the extent of the cash surrender value of the policy, I believe an argument can be advanced that the amount of the gift is actually the fair market value of the policy. Such a position would only be beneficial if it did not entail recognition of income equal to such a fair market value. Section 148 of the Act dictates that the income triggered on the disposition of a policy cannot exceed the proceeds the policyholder (or beneficiary) is entitled to receive in the year of the disposition. If all the policyholder(or beneficiary) is entitled to receive is the cash surrender value, then the income limit is set. On the other hand, Section 69 of the Act deems a donor to have received proceeds of disposition equal to the fair market value of the property that has been given.If a deemed receipt of proceeds of disposition is not a deemed entitlement to proceeds of disposition, then the way seems open to recognize the true value of a policy as a gift without triggering a corresponding income amount.

As a final word, I might note that in addition to using insurance as a means of raising money through the receipt of death benefits, a charity can also use it as an adjunct to other giving programs. For example, interest-free loans repayable at death could be converted by the charity to immediate “gifts”of the principal amount of the loan by taking out insurance coverage sufficient to repay the indebtedness.

FOOTNOTES

1. Editor’s Note: This paper was prepared for, and presented at, a Tax and Law Forum for Non-Profits sponsored by The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy (Manitoba), on October 22, 1986 prior to the tabling of Tax Reform measures on June 18, 1987 (Tax Reform). The paper has been reviewed by the author and certain revisions and additions have been made. The general thrust of the paper remains valid but readers should be careful to consider the impact ofTax Reform and other statutory enactments or specific proposed amendments made since October 22, 1986.

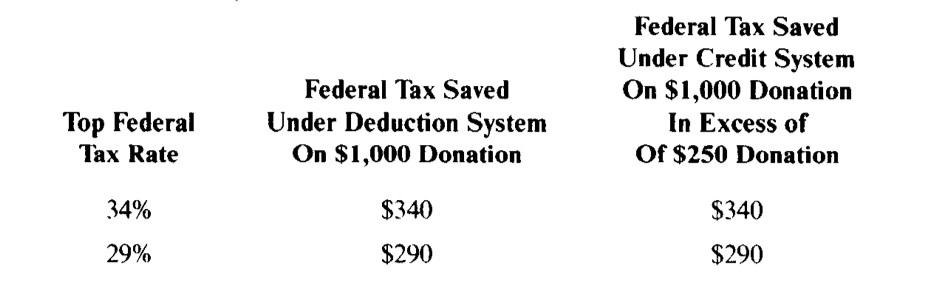

2. The charitable donation deduction for individuals has been converted into a charitable donation credit for 1988 and subsequent taxation years in accordance with the general conversion of personal deductions to credits announced in Tax Reform. A credit of 17 per cent (the lowest marginal rate of federal tax) will be allowed for the first $250 of charitable gifts and 29 per cent (the highest rate of federal tax) for the balance. The provinces will, presumably, follow suit by providing a similar credit against provincial tax.

While the change from a deductible system to a credit system under Tax Reform will be beneficial to individuals in lower income brackets, it does not adversely affect higher income earners as is shown in the following chart. (However, deductions and credits arc equally less valuable as a result of the lowering of tax rates under Tax Reform.) (See image below)

The charitable donation deduction system for corporations remains unchanged as a result of Tax Reform but, again, lower tax rates for corporations decrease the tax savings associated with corporate charitable gifts.

The charitable donation deduction system for corporations remains unchanged as a result of Tax Reform but, again, lower tax rates for corporations decrease the tax savings associated with corporate charitable gifts.

3. 85 D.T.C. 5433 (Fed. C.A.). (Editor’s note: See also, ‘”Recent Tax Developments”, Vol. V, No.3, Fall/Winter 1988, pp. 49-50.)

4. However, a recent example of a successful challenge by Revenue Canada is The Queen v. Bunns, 88 O.T.C. 6101 (F.C.T.D.), in which the court held, following the McBurney decision, that donations made by the parent of a skier to the Canadian Ski Association were not ‘”gifts” for the purpose of the Act.

5. The recent case of Tite v.M.NR., 86 D.T.C. 1788 (T.C.C.), supports this view. In that case a charity sold paintings for a certain ‘”price” and issued a charitable receipt for a portion of that ‘”price”. The court held that gifts had not been made to the charity and, accordingly, no charitable receipt could be issued for any portion of the ‘”price”.

6. Information Circular, IC 75-23.

7. Interpretation Bulletin, IT-110R2, paragraph 8.

8. See, for example, Olympia Floor & Wall Tile (Quebec) v. M.NR., 70 D.T.C. 6085 (Ex.Ct.).

9. Under Tax Reform the maximum amount of charitable donations in a year available for the credit will also be 20 per cent of a taxpayer’s net income with the ability to carry forward any excess for up to five years. The carry forward will also apply to gifts carried forward from 1987.

10. The credit system proposed by Tax Reform should generally neutralize the impact of either low-income years or high-income years.

11. As stated in Footnote 2, the donation deduction system will be unchanged for corporations so that this comment will remain valid under Tax Reform.

12. The top marginal rate in Manitoba following Tax Reform is expected to be approx- imately 50 per cent for 1988.

13. Antoine Guertin Ltee. v. The Queen, 81 D.T.C. 5045 (F.C.T.D.).

14. Subsection 75(2).

15. Subsection 69(1).

16. Paragraph 110(1)(b).

17. Paragraph 110(1)(b.l).

18. Subsection 110(1.2).

19. Subsection 110(1.2).

20. Paragraph 149.l(l)(e).

21. The exemption was capped at $100,000 as a result of Tax Reform except for gains realized on dispositions of shares in a small business corporation and farming property. The $100,000 exemption was fully phased in in 1987 and the $500,000 exemption for shares in a small business corporation and farm property is effective in 1988.

22. Subsection 110(2.2).

23. Interpretation Bulletin, IT-288, paragraph 2.

24. Supra, Footnote 17.

25. Subsection 110(2.3).

26. Interpretation Bulletin, IT-110R.2, paragraph 13.

27. Paragraphs 110(1Xb) and 110(1)(b.l).

28. The same point would apply in the credit system proposed in Tax Reform, i.e., a credit is only of benefit if there is a tax benefit in the year of death or a carry back year.

29. See Canada Tax Planning Service, Vol. 3, at 24-35 and 36.

30. Editor’s Note: See also R.C. Knechtel, “The Case Against Gift Annuity Programs”,

The Philanthropist, Vol. VI, No.2, Summer 1986, pp. 3-13.

31. Paragraph 149.l(e.l).

32. Interpretation Bulletin IT-244R2, paragraph 3.

33. Subparagraph 149.1(1)(eXi) and paragraph 149.1(2)(b).

34. Supra, Footnote 31, paragraph 2.

JOE E. HERSHFIELD

Taylor Brazzell McCaffrey, Barristers and Solicitors, Winnipeg

Note from October 1988: In our Spring 1988 issue (Volume VII, Number 3), Joel Hershfield discussed “Tax-Effective Charitable Donations”. His note on gifts in-kind (pp. 47-48) had, in one aspect been overtaken by amendments to the Income Tax Act, a fate that threatens all advisors on tax matters.

Specifically, the Act was amended by S.C. 1986, c.6, to allow an election of a specified value for a gift-in-kind to charities regardless of the type of gift In other words, the election is no longer limited, as was stated in the article, to gifts of tangible capital property. This means that stocks and bonds, for example, would now qualify for the election.

The other rules and limits set out in the article continue to apply.