Introduction

The British are historically avid supporters of charity, giving around £1 billion each year to local, national and international causes. They give to street collectors rattling tins, to national television appeals, via their payrolls, by purchasing second-hand clothes in charity shops and in a host of other ways. However, current evidence points to a fall in charitable giving. In 1993, 81 per cent of Britons gave a total of £5.3 billion, compared with 66 per cent giving a total of £4.9 billion in 1998, a decline of more than 20 per cent when inflation is taken into account. In other words, there was £1 billion less to spend on services for some of the most disadvantaged people in Britain and across the world and 15 per cent of the population no longer engaged in an activity seen by many as a key indicator of social solidarity. Why has such a decline occurred? This paper will not deal in positivist notions of cause and effect; however, the launch of the UK National Lottery around the time of the start of the decline introduced a new multi-billion-pound “consumer” of disposable income into the marketplace. It is the biggest lottery in the world, backed up by a £30-million annual marketing budget.

Background To the UK National Lottery

It should be remembered that a national lottery is not new to Great Britain. The first was held in 1569 to raise money for the construction of the Cinque Ports, a bulwark against invasion from continental Europe. Other lotteries funded Westminster Bridge (1739) and the establishment of what eventually became the British Museum (1753). Thereafter, opposition grew to national lotteries because of widespread illegal gambling on the outcome and “because of the social evils that were perceived to be their constant and fatal attendants” (NCVO, 1993: 12). Whether this is a portent for the current lottery remains to be seen.

The latest UK National Lottery was launched with a fanfare of publicity in November 1994. The It Could be You message immediately captured the public’s imagination and ticket sales totalled almost five billion per year over the lottery’s first three years- since when there has been some trailing off. This turnover exceeded even the highest estimate of 2.96 billion ticket sales per year (NCVO, 1992).

Lottery revenues are allocated in specific proportions. The lottery prize fund takes around half of the revenue, retailer commissions account for five percent,

the operator (Camelot) takes around five per cent to cover running costs and profit, and 12 per cent goes into Treasury coffers. The Government thus has a direct financial stake in ensuring a successful lottery. The balance is distributed by lottery distribution boards to a range of “good causes”. One of these boards, the National Lottery Charities Board (NLCB) is specifically charged with funding voluntary sector activities. The National Lottery White Paper proposed arts, sport, heritage and a “residual amount” for charities, and the Conservative party’s 1992 election manifesto proposed a further cause—the Millennium Fund. As a result of lobbying Jed by NCVO, charities were recognized as a good cause on a par with four other good causes.! A further Act in 1997 added two new distributors: the National Endowment for Sports, Technology and the Arts (NESTA) and the New Opportunities Fund. In total, the good causes have received around 28 per cent of total lottery revenue, the equivalent of more than £1 billion each year.

Policy Issues and Developments

The government consistently argued that lottery funding would be additional to existing support. During the passage of the original legislation in Parliament it argued that evidence about the likely impact of national lotteries on charitable giving, particularly from Ireland where a national lottery had recently been established, was mixed; the element of charitable income most likely to be affected was that from charity lottery or raffle ticket sales, and it was relaxing the regulation of these lotteries in an attempt to maintain sales and, in the areas of arts, sport, heritage, and millennium projects, the bulk of the money would be spent on capital projects to distinguish it from the revenue grants-in-aid provided by central government to the first three.

Originally, the NLCB was the only board able to make revenue grants- the others made capital awards for buildings and other infrastructure which needed to attract a level of matched funding from other sources. However, the higher than predicted level of ticket sales, coupled with a lower level of matched funding than forecast (especially from business) essentially meant there was not enough money to match lottery awards. As a result, matching levels were relaxed, grants policies were changed to enabling revenue funding, and volunteer labour was allowed to be considered as a form of matched funding.

In 1996, criticism grew regarding the ad hoc nature of lottery grantmaking, with the Conservative government following a philosophy of “letting a thousand flowers bloom”. Geographical and socio-economic disparities in grantmaking became a political issue. The Labour Party seized the initiative with a detailed review of lottery policy from which it developed the idea of “A People’s Lottery”. Under a Labour government, they promised, the lottery would work in a strategic fashion with other funders and government to address social and economic problems; it would fund the priorities of the public; and it would be able to solicit bids from disadvantaged communities. The lottery was thus tied into an emerging agenda designed to tackle social exclusion and would support activities in the health and education fields- two of the pillars of the welfare state. In so doing, the present Labour government has opened up the issue of additionality, i.e., the belief that lottery funding should never be a substitute for state support.

Charitable Giving In the UK: The Context

NCVO consistently highlighted the need to monitor individual giving once the lottery was up and running. In 1992 NOP [a national polling organization] were commissioned to undertake research into the lottery’s likely impacts on charitable giving. The results suggested the sector was unlikely to be a net gainer from the lottery. As a consequence, NCVO has commissioned NOP to conduct surveys of individual giving in Great Britain since late 1994. The aim is to provide a new estimate of charitable donations, a detailed understanding of charitable giving, and an assessment of whether the National Lottery was affecting charitable giving by the general public.

In order to link the NCVO research with that undertaken up to 1993, NOP were commissioned by NCVO to carry out benchmark research in November 1994 (prior to the advertising campaign to launch the lottery), using a broadly comparable methodology for this consumer research. The 1994 results (with a month recall they refer to giving in October 1994), were consistent with those from 1992 and 1993. In addition, NCVO added additional attitudinal questions relating to charitable giving, lottery playing, and the impact of the lottery on charitable giving. The rest of this paper briefly reports on some of the findings from 1995 and 1996- the time when the relationship between the lottery and charitable giving was a key focus of policy debate.

Charitable Giving and Lottery Playing

Patterns of giving and playing

The pattern of givers remains broadly similar year-on-year, with women more likely to give than men; those aged below 25 or over 55 less likely to give; people from higher social classes (ABs) the most likely to give, as were people living in southern or northern England; and married people. The patterns of amounts donated are more volatile with, on average, women giving more than men in 1996 (the opposite of 1995) and lower social classes (DEs) giving a fifth of the average amount given by ABs. The most generous donors lived in southwest or southeast England, in owner-occupied housing and had children living in their households.

Men play the lottery more than women; middle aged people more than people of other ages; people in social class C2 have the highest rate of playing, as do people living north and west of the Midlands, council renters, married people, and those who did not stay in full time education after the age of 16. Patterns of spending on the lottery are stable with, on average, those aged 65 and over spending the least; DEs spending the most; and men spending more than women.

Average giving by players and nonplayers

While in 1996 the mean monthly donation for all respondents was £8.69, on average nonplayers gave more than lottery players (£10.55 as opposed to £7.47). Because the sample was selected randomly, it is possible that this difference is merely the product of chance, and that if a different sample were drawn there would be no difference in giving between the two groups. We can, however, turn to statistical tests to determine whether this difference is indeed due to chance (sampling error) or whether it does reflect actual differences in the value of charitable donations between people who played the lottery and those who did not.2 Based on this test, we are able to conclude that:

• There was a difference in the level of giving between players and nonplayers in 1996;

• Nonplayers gave more than their lottery playing counterparts.

However, it should be noted that while the students’ t-test does show differences between respondents, it does not prove causality, i.e., that playing the lottery caused respondents to give less to charity.

Public Attitudes Towards the National Lottery and Charitable Giving

In order to examine the relationship between attitudes to the lottery and charitable giving, a summative score of responses to each of the attitude statements about the lottery was calculated. Respondents were then divided into two groups depending upon their score:

• respondents with positive to very positive attitudes towards the lottery;

• respondents with negative to highly negative attitudes towards the lottery. The students’ t-test was employed to examine a number of hypotheses about differences in behaviour and attitudes between respondents with positive or negative attitudes towards the lottery) On the basis of the results, it is possible to conclude that those people who had negative attitudes towards the lottery:

• gave more to charity;

• felt the lottery raised less money for the five good causes and specifically for charity;

• bought fewer lottery tickets,

compared with people who had positive attitudes towards the lottery.

Another way of analyzing public attitudes towards the lottery and their possible impacts on charitable giving is to examine the responses to various questions depending upon whether respondents did or did not feel the lottery was a good way of helping charity.

In the surveys, respondents were asked how much of each lottery pound they felt went to the five good causes and then how much they thought was earmarked specifically for charities. On average, respondents thought 32.8 pence went to the five good causes and 19 pence specifically went to charity. This suggests there is some public conflation between a National Lottery “good cause” and charity. This may have stemmed partly from lottery operator Camelot’s first wave of advertising that promoted the lottery as benefiting charitable good causes, a theme echoed in their poster campaign launched in early 1996.

In order to examine this apparent public confusion further, the range of respondents’ estimates of the amount going specifically to charity was divided into quartiles. Next, the percentages of respondents within each quartile agreeing or disagreeing that the lottery is a good way of helping charity were calculated. Analysis reveals that as respondents’ estimates of monies raised specifically for charity increases, so too does the proportion of respondents feeling the lottery is a good way of helping charity—from 49.1 per cent in the bottom quartile to 67.6 per cent in the top. However, while the overall estimates suggest confusion over the amount specifically earmarked for charity, it is possible that respondents overestimate this figure as post facto justification for purchasing lottery tickets. The students’ t-test was again used to examine a number of hypotheses about differences in behaviour and attitudes between respondents agreeing or disagreeing that the lottery is a good way of helping charity .4 In 1995 those people who did not agree that the lottery was a good way of helping charity:

• gave more to charity themselves;

• felt the lottery raised less money for the five good causes and specifically for charity;

• bought fewer lottery tickets;

compared with those who agreed that the lottery was a good way of helping charity.

Has the National Lottery Affected Charitable Giving?

Analysis of the 1996 consumer research data shows a drop in the proportion of people donating to charity since the lottery was launched and suggests that overall donations fell in real terms by 20 per cent between 1993 and 1996, with 14 per cent of that fall between 1995 and 1996. This is derived from using the mean figure of respondents who said they had given to charity by all methods. The aim of this section is to explore whether this observed decline in participation and total donations is related to the lottery and, if so, to attempt to quantify it.

Since giving to charity is viewed by the majority of the public as a socially desirable activity, one would expect respondents to underestimate any impact of the lottery on their charitable giving. As a consequence it was necessary to frame questions in a way that would limit the effects of social desirability. Following standard questionnaire procedures, (such as de Vaus, 1991), these sensitive questions were placed at the end of the questionnaire, and they included responses showcards where each possible answer was assigned a letter. In this way respondents simply had to give the letter that matched their response. The questionnaire also contained a filter question that split respondents into two distinct groups:

• lottery players who reported making a charitable donation in the past month

• lottery players who reported they had not made a charitable donation in the past month.

The former were asked separately about any impacts on different methods of giving. In an attempt to further limit the problem of social desirability, respondents were given a range of possible responses, each of which was then weighted to produce an estimate of the overall impact.S

Using this methodology, charitable donations were estimated to have fallen by 7.2 per cent in 1996 through members of the public switching their expenditure to the purchase of lottery tickets. The midpoint estimate of total charitable donations in 1995 was £5.229 billion (Hems & Passey, 1996), and using this figure as a base, the 7.2 per cent estimated loss in 1996 amounts to £376 million (on top of the £339 million loss in 1995). This is around half of the estimated 14 per cent real fall in charitable donations between 1995 and 1996 that was measured by the consumer expenditure questions in the survey.

Conclusion

The research briefly summarized here is not an attempt to prove a cause and effect relationship between the emergence of the lottery and the decline of charitable giving in Great Britain. We are dealing with economic and social phenomena, not the kind of medical research where test/retest models of research are used in the development of new drugs, for example. However, the tests undertaken do point to a correlation between the lottery and charitable giving.They suggest that public attitudes and behaviour are related, especially since people with generally negative attitudes to the lottery buy fewer tickets and give more to charity than other members of the population.

FOOTNOTES

1. The other four original boards are: The Sports Council, The Arts Council, National Heritage Memorial Fund and The Millennium Fund.

2. One simple procedure is the t-test, for which we must first state what is termed the alternative hypotheses. In this case:

• people who did not play the lottery gave more to charity in 1996. Conversely, the null hypothesis states that:

• any differences in giving between players and nonplayers in the sample are random and the product of chance, and do not reflect differences in the GB population.

Table 1: Mean giving by players and nonplayers

|

Degrees of freedom |

tobt |

tcrit |

1 tailed significance |

|

13,838 |

-5.31 |

1.645 |

0.05 |

Source: NCVO/NOP

Assessment of the t-test statistics has two stages (see Table 1). First the magnitude of the obtained t value (ignoring whether or not it is positive or negative) is compared with the critical value for t. As the table shows, the magnitude of the obtained value for t is markedly larger (5.31) than the critical value for t (1.645) and so we can conclude there is a difference between players and nonp1ayers. Second, because the obtained value fort is negative (and because of the way the information is coded) we can conclude that lottery players gave less to charity in 1996 than nonplayers. This means there is only a 5 per cent probability that there is no difference between the two groups.

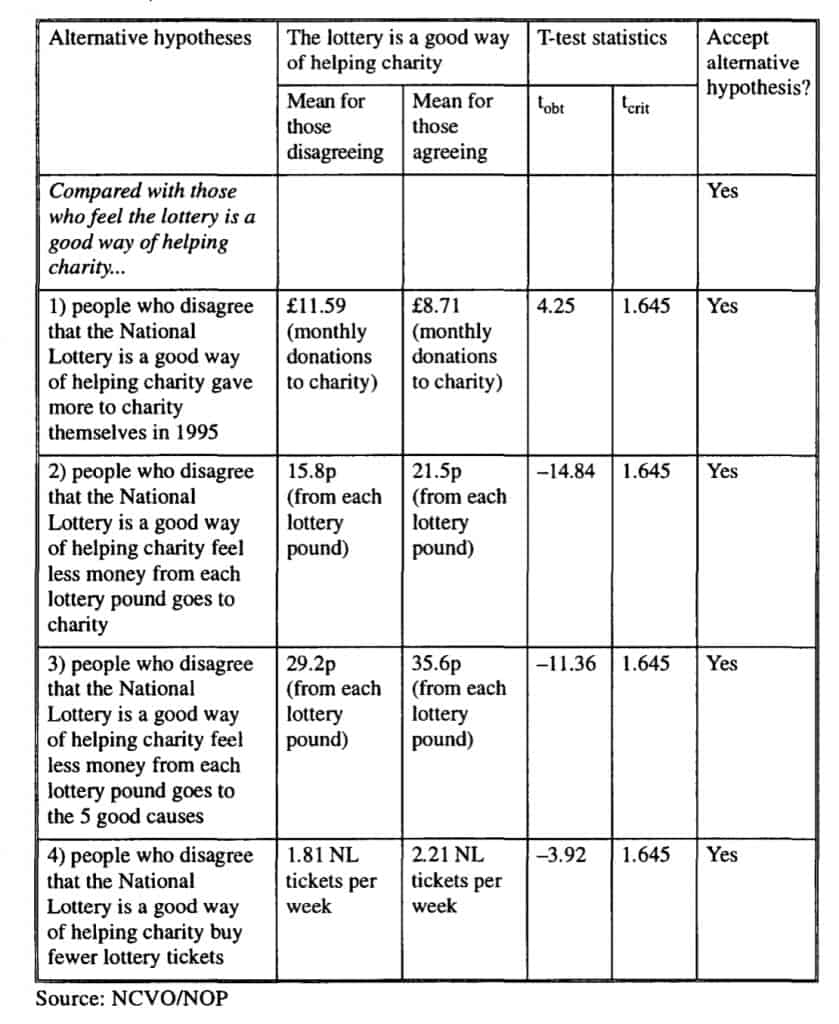

3. Each of the hypotheses tested and the results of the tests are summarized in Table

2. Each test was uni-directional (i.e., it measured not just whether there were differences but also their direction), and the sensitivity level was set at 0.05, meaning one can be 95% confident in interpreting the results.

Table 2: Perceptions of amounts accruing to charity and attitudes to the lottery

| Bottom | Second | Third | Top | |

| The National Lottery is a good way of helping charity… (% agreeing by quartile) |

49.1% | 42.4% | 61.9% | 67.6% |

Source: NCVO/NOP

A glance at the table shows that, in all cases, the means (averages) are different. Using the t-test however, it is possible to assess whether these differences are simply due to chance (i.e., the result of sampling error- the null hypothesis) or whether they reflect actual differences in the GB population. To do so, it is necessary to compare the obtained value for the test (tobt) with its critical value

(tcrit)·

Table 2 shows that all the alternative hypotheses can be accepted.

4. The hypotheses tested and the results of the tests are summarized in Table 3. As before, each test was uni-directional and the sensitivity level was set at 0.05, meaning one can be 95% confident in interpreting the results.

Table 3: Comparison between respondents seeing or not seeing the lottery as a good way to help charity

If we are to accept the first hypotheseis then tobt would need to be larger than tcrit (we want to know if those with negative attitudes gave more to charity); to accept the three remaining hypotheses tobt would need to be a larger number than tcrit but with a negative sign (we want to know if those with negative attitudes gave lower answers).

Each of the alternative hypotheses can be accepted.

5. The details are outlined in Table 4 below, which is based upon the method used by the Henley Centre in its 1992 report The Likely Economic Impact of the National Lottery.

Table 4: Weighting of lottery impact question

|

Choice of response |

Weighting for impact |

|

Playing the National Lottery has… Replaced my giving Considerably reduced my giving Slightly reduced my giving Had no impact on my giving Increased my giving Don’t know |

-100 per cent -75 per cent -25 per cent 0 +25 per cent -50 per cent |

Source: The Henley Centre

Non-givers who had played the lottery were asked whether playing the lottery had either:

o replaced their giving to charity

o made no difference because they never gave

o don’t know

Responses here were coded more cautiously, since only three categories are used. Once again, replacement was givenaI00 per cent weighting, whilst the other two responses were given a zero weighting.

ANDREW PASSEY

Head of Research, National Council for Voluntary Organizations

(NCVO), London, UK