In the second iteration of its participatory grant fund, the Foundation for Black Communities aims to reach more communities and needs. Recipients of the first round of the Black Ideas Grant share what they’ve gained and what’s missing from foundation grants in Canada.

The Foundation for Black Communities (FFBC) announced its second investment in Black communities – but this time, it is granting more money and recruiting more community members to vote on which organizations get the grant. The Black Ideas Grant 2.0 will provide $9.5 million to Black communities across Canada next year, compared to the $9.1 million investment it awarded in May. Organizations will submit applications about projects focused on combatting anti-Black racism and improving social and economic outcomes. FFBC aims to have 330 Black people reviewing and selecting grantees compared to the 250 involved in the previous participatory grantmaking process. According to Nneka Otogbolu, FFBC’s chief operating officer, it’s their hope that more diverse perspectives will “enrich the decision-making process.”

FFBC awarded 107 grantees out of the 2,000 applicants in the first round of funding. For some, B.I.G. was their first grant after a series of rejections. The funding helped others establish community projects whose return is highly anticipated. Representatives from the Rwandan Canadian Healing Centre (RCHC), the African and Caribbean Association of Nunavut (ACAN), and the Association Djiboutienne pour autisme et autres besoins (Djiboutian Association for Autism and Other Needs; ADAB) shared their thoughts on the key differences in applying for grants specifically for Black communities and evaluated by Black people.

Flexible funding options

B.I.G. 2.0 provides one year of funds to Black-led, Black-focused, and Black-serving (also known as B3) organizations in Canada. The community members and fellow applicants choosing the recipients – the community selection circle – can be nominated or self-nominated and then selected by an external consultant. Though the funding streams are similar to B.I.G.’s first iteration, there are some differences.

The core stream awards up to $30,000 to address organizations’ operational needs outside of programming, compared to the $40,000 cap from the last fund. The catapult stream awards up to $80,000 to invest in new or existing programs and services instead of up to $100,000; ACAN and ADAB were awarded this stream earlier this year. The community spaces stream, previously called the community capital stream, funds up to $200,000 to invest in capital projects and social infrastructure. RCHC received $250,000 from this stream earlier this year.

Otogbolu explains that these changes are a response to the “oversubscription” of grant applications – FFBC wanted to share more wealth with applicants.

Awarding critical support for organizations to build momentum

ADAB is a four-year-old organization that moved out of a basement and into an office two years ago and is fully volunteer-run – all of whom are parents of children with autism. “We are so busy; it’s a lot of challenges. [It’s] time-consuming. The only thing that made us able to make it was because we love this organization,” says Oumalkaire Assowe, ADAB’s vice president.

The catapult funding allowed ADAB to plan more activities for children with autism and workshops to support parents taking care of them. They took the children to “zoo therapy” where they could feed animals, which eased the children’s anxiety. In one workshop, a doctor discussed the connection between the brain and gut health, explaining how changes in diet and nutrition could improve behaviour. The funding allowed ADAB to hire a French translator for the session, since most ADAB members are francophones of Djibouti descent. (Assowe notes that it is “rare” to find French-speaking professionals in Ontario.) They were also able to submit their funding application in French, which has been a barrier in the past.

ADAB plans to use the rest of the fund to run workshops to bridge knowledge gaps among parents with newly diagnosed children, especially for Black families. “I know that a lot of Black families don’t know that sensory materials exist,” Assowe says, referring to toys or objects that stimulate senses of sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste. “It hugely helps kids to calm down from anxiety, so we show them those tools exist.”

ADAB hired male monitors to help with their family programs, to keep children from running away and keep them safe when interacting with each other, which is especially helpful because many mothers come to ADAB activities without the support of husbands or partners.

We were directing them to the resources, but we didn’t have the money to really bring the professionals right to our events so that the parents can ask questions and get more knowledge.

Hasna Farah, Djiboutian Association for Autism and Other Needs

Treasurer Hasna Farah says she wants to get enough funding for ADAB to be able to pay for resources and professionals to help these families. “We were directing them to the resources, but we didn’t have the money to really bring the professionals right to our events so that the parents can ask questions and get more knowledge.” She also wants funding so families can get occupational therapy, instead of paying out of pocket like she and Assowe have done in the past.

Although grateful for the grant, Farah says it is difficult to spend the funding within one year. “Planning needs at least six months to find places to go, bus availability, monitor availability, parent availability.” She says that they already had a list of places they wanted to take the kids and in summer “every place was available, [but] I understand that’s going to be harder now.”

Otogbolu says FFBC’s funding options may evolve as the foundation does. “We’re hoping the more we learn about the pressures in the community, we are able to step back and say, ‘Hey, are there ways we could design multi-year grant streams for organizations?’ But we don’t know what we don’t know.”

Providing opportunities to expand the vision

For other organizations, B.I.G. provided the means to expand their mission.

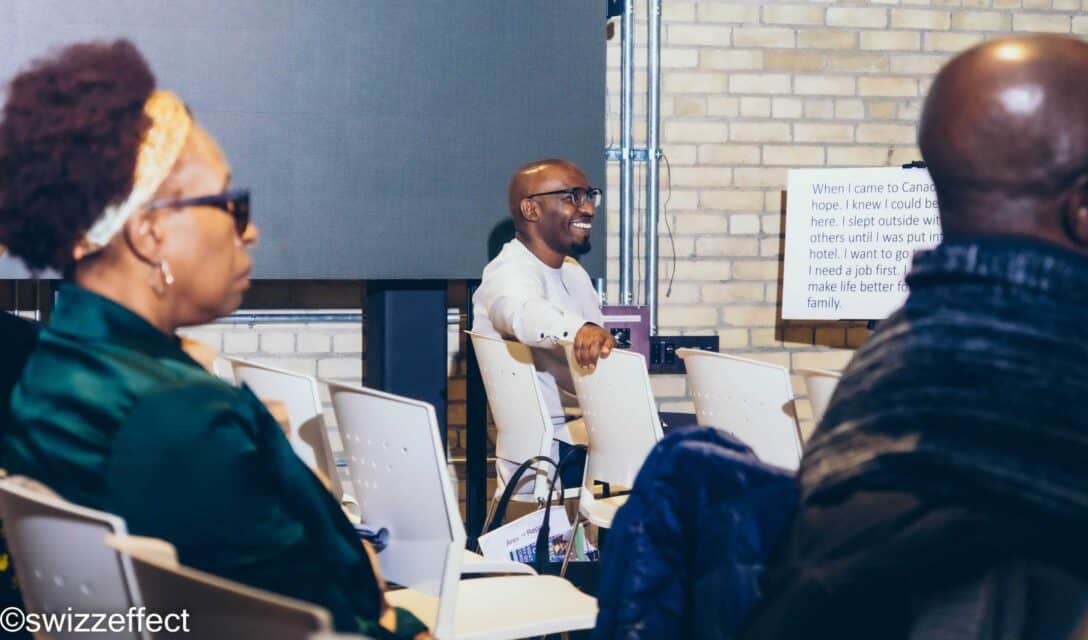

The Rwandan Canadian Healing Centre is trying to establish an African Canadian affordable-housing village model, a multimillion-dollar project that is part of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s African Canadian Affordable Housing Lab. But this wasn’t always the plan – and it wasn’t why they applied for B.I.G. Led by president Kizito Musabimana, RCHC was born from a desire to support others while he, too, processed and recovered from the trauma of the genocide of his people in Rwanda. While a healing centre for Rwandans is still at the heart of RCHC’s mission, it now encompasses the pan-African community, including refugees and asylum seekers.

The FFBC fund allows us to shift from just thinking about the healing centre to now thinking, how do we build a village?

Kizito Musabimana, Rwandan Canadian Healing Centre

The FFBC fund was the RCHC’s way to focus on the potential for a community hub for Canada’s Black community. “Everything we’re doing now is kind of coming from that specific grant and the initiative, and it allows us to shift from just thinking about the healing centre to now thinking, how do we build a village?” Musabimana says. “The healing centre is in the middle of it . . . The community hub is also dressed around the healing piece. Everything we’re doing is to create a safe space for our community.”

Musabimana says that support from other communities and associations like the Ghanaian-Canadian Association of Ontario and the Eritrean Canadian Network (which operates as New Nakfa) is also advancing the affordable-housing model. “If we say we want to create an interconnected community, what does that mean? We want a village where people can support and walk and do everything collectively, like we do on the continent [of Africa],” he says.

Other Housing Lab partners applied to B.I.G., but RCHC was the successful grantee. Though RCHC was awarded the largest stream – community spaces – it still has a long way to go to make its vision a reality. Musabimana estimates needing around $170 million to see this village through – and with that, the zoning permission, land sales, staff, and programming to make it happen.

He says that RCHC has been applying for grants since 2018 but has had only occasional success. They don’t bother applying to the Ontario Trillium Foundation anymore, he says, because all five of their applications have been declined. Sometimes they didn’t meet the qualifications or have the necessary financial statements; other times, they were told their application was incredible and the rejection just came down to competition.

“OTF is only able to fund a limited number, so we understand that many organizations are disappointed when they are not approved for a grant,” an OTF spokesperson writes in an email. “Over the last number of years there has been a significant increase in funding requests and the demand is very high for grant dollars.”

Prioritizing Black funding

The African and Caribbean Association of Nunavut (ACAN) promotes economic, social, and cultural well-being for people of African, Caribbean West Indian, and Afro Caribbean descent. It launched in 2018, is volunteer-run, and has roughly 120 members (of the approximately 565 Black people living in Nunavut).

Kabelo Mokoena, ACAN’s president, says it is difficult for ACAN to receive funding in Nunavut because most funding is focused on Inuit, who make up more than 86% of the population. “We cannot compete with another marginalized group because they’re trying also to have their own culture out there and their fight,” Mokoena says. “But it’s very difficult for African organizations to get funding directly.”

It’s very difficult for African organizations [in Nunavut] to get funding directly.

Kabelo Mokoena, African and Caribbean Association of Nunavut

Mokoena says that while ACAN is geared toward the African community, they celebrate the diversity of Iqaluit. “We also have other Inuit folks who are part of the African community by marriage or by birth . . . We have to try to make sure that everybody is also covered,” he says. “Most of our plight, our Inuit people carry it. Most of our issues that we go through, Inuit people understand it . . . We are interconnected.”

“The Inuits are the beneficiaries of the land, but we are all living together in harmony, so we make sure our programming encompasses everyone,” says Nyasha Kamera, ACAN’s grant coordinator.

Kamera says that ACAN had three or four applications rejected this year before they learned about FFBC’s grant and switched gears to focus on a specific event: the Iqaluit Run 2024. ACAN organized the Iqaluit Run to gather the Nunavut community for a shared event that everyone could participate in. The B.I.G. funding covered operational expenses, materials, transportation, volunteers, and more. There were two-, five-, and 10-kilometre races, with attendees coming from Iqaluit and the surrounding area, including the deputy mayor, the RCMP, and 30 to 40 people who were not originally registered.

Mokoena was encouraged by the turnout, considering how cold and windy it was on race day. He’s hoping for a sunnier day and an even better turnout next year – and that FFBC will be there to “double” the funding.

But Otogbolu points out that organizations that have received the B.I.G. funding cannot apply again. “We’re trying to ensure that we’re equitable with our practices. If you have access to the funding now, you’re already in the middle of your grant steam,” she says. “It will only be fair to give all the groups opportunities to apply and get funded as well.”

FFBC looks forward to seeing how the increased engagement through our expanded community selection circle would allow us to address a broader variety of needs within the Black communities across the country.

Nneka Otogbolu, Foundation for Black Communities

Otogbolu says that FFBC looks forward to seeing “how the increased engagement through our expanded community selection circle would allow us to address a broader variety of needs within the Black communities across the country.”

B.I.G. 2.0 applications closed on November 8, but B3 organizations are in need of more granting opportunities to help Black communities – and their neighbours.

“The reason why we had [the race] was to bring the whole community together to celebrate our diversity and appreciate each other, because there are a lot of challenges that we face working up in the North, and they don’t only affect us,” Mokoena says. “They also affect the Inuit. They affect the Asian population, the white population. Everybody’s affected, but when we come together and make things easier for each other, it works out . . . That kind of funding is not guaranteed.”

***

Editor’s note: This article was updated on November 12, 2024, to use the correct name of the Eritrean Canadian Network (which operates as New Nakfa).