Many in the charitable and non-profit sector want to get to the roots of problems and evolve new ways of doing things, in addition to addressing the symptoms, but how does systemic change actually happen? In this article, one organization shares its journey and key learnings.

Systems change – you want it, we all want it. But how do we do it?

Many environmental and social justice organizations express the need for systemic change. We want to go to the roots of problems and evolve new ways of doing things, in addition to addressing the symptoms. This is a meaningful and honest goal, but understanding how to bring it about can be like walking on a muddy field in the fog. Where do you go? How do you know you are headed in the right direction? How to avoid getting stuck in the muck of everyday work?

Where do you go? How do you know you are headed in the right direction? How to avoid getting stuck in the muck of everyday work?

In this article, we share the story of one organization’s path to clarify for itself what systems change means and what role it can best play. This work brought about a profound shift in how the organization sees itself, positively influencing its strategy, programs, team dynamics, partnerships, and impact assessment. (Full disclosure: Natalie Brown is the program director at Park People; Tania Cheng and Juniper Glass were hired as consultants to facilitate and guide the team during this process.)

How Park People started thinking about systems change

Park People is a national, bilingual organization dedicated to championing city parks in Canada. We believe that parks are vital to the health of Canada’s cities and our environment and that everyone – regardless of their income, identity, ability, or age – deserves equal access to the benefits of public green space.

Park People was founded in 2011 in Toronto and expanded its work nationally in 2016. Today, Park People creates opportunities for local residents, non-profits, government, business, and philanthropy to work together to support new possibilities for our city parks, and we provide them with the tools they need to sustain great parks in their communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to an explosion in public interest in city parks and green spaces. Almost overnight, the Park People team went from painstakingly making the case for the importance of parks to having folks nod vigorously before we even finished our pitch. People now viscerally understood how important these spaces are. Park People’s programs and team grew rapidly in response to this societal shift.

Six months into the pandemic, the Park People team gathered on Zoom to try to regroup. We asked ourselves: What is the future of parks and public spaces in Canada? What is the short-, medium-, and long-term role of Park People? We imagined several possible futures for Canadian city parks. In one, there were massive cuts to public park funding, similar to what has happened in the United Kingdom and parts of the United States.

Public funding cuts create opportunities for non-profits to fill gaps. Park People could potentially grow a lot in this dystopian future. But we realized that this type of “success” would be a failure for Park People. A future where the organization grew because publicly funded and publicly managed parks were weak was not what we wanted. We needed to start strategizing for system-wide change as the truest measure of Park People’s organizational impact. But how?

Early explorations of Park People’s purpose and role in systems change

In late 2021, we began rethinking our theory of change, integrating this understanding that Park People intended to help bring about meaningful, widespread change in the city park system.

First, we developed a new set of organizational values and identified the key parts of our approach (how we work). Whittling down to just three values made this a tool that everyone could use and brought energy through clarity. The Park People team would gut-check the work as we went along by referring back to the values and approach, making sure we were still aligned with them.

Our first go at the theory of change was based on the traditional logic-model format, depicting a linear set of “if–then” causal relationships intended to connect our short-term activities to long-term impacts. It was a big step forward in clarifying which stakeholders Park People aimed to influence and how, but it gave the impression that Park People’s work is linear. As an organization that works to foster networks and relationships where different stakeholders collaborate, compressing our work into a single pathway of sequential actions felt misleadingly simple.

Work in progress: Early attempts at the theory of change

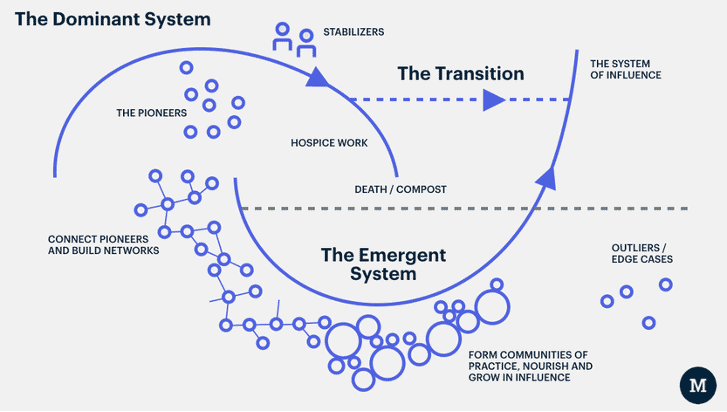

The consulting team heard in our discussions that Park People wanted to bring about profound change, but there were as many ideas about the “what” and “how” as there were members of the team. To bring clarity to the chaos, the consulting team pulled together several different conceptual frameworks that attempt to describe how systems change happens. We considered interesting models like the Power Shift framework and the three types of scaling but found one that was an even better fit: the “two-loops” framework from Berkana Institute.

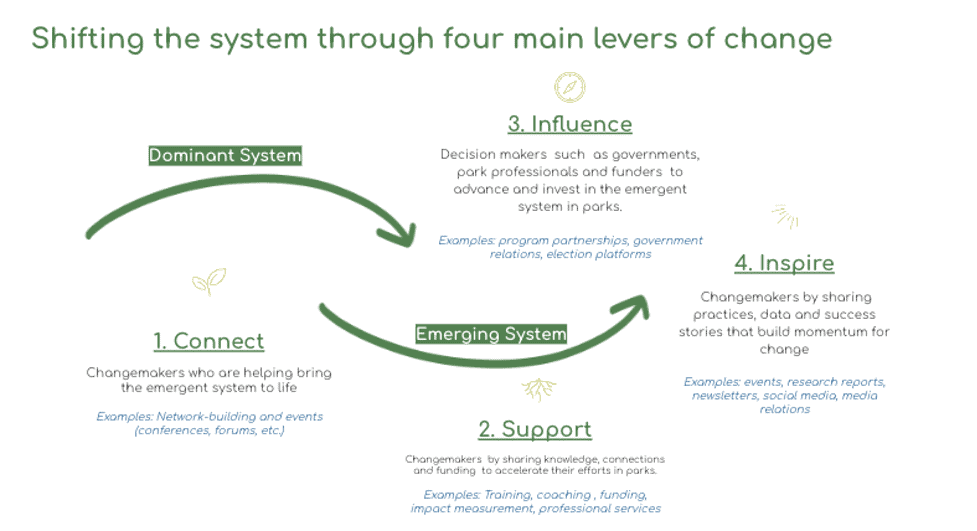

The two-loops framework envisions that systems transform through the decline of a “dominant system” and the growth of an “emergent system.” Multiple roles for system actors are identified across both systems to advance change. This framework can be particularly helpful for organizations straddling both systems – those that are trying to retire old ways of doing things while creating space for new approaches.

The two-loops model resonated immediately: it was a thoughtful, holistic articulation of how we already thought about our work at Park People and a powerful counter-narrative to the dystopian futures we had imagined back in 2020. We knew we had found The One when it was so easy to talk about the model with our colleagues – they got it immediately.

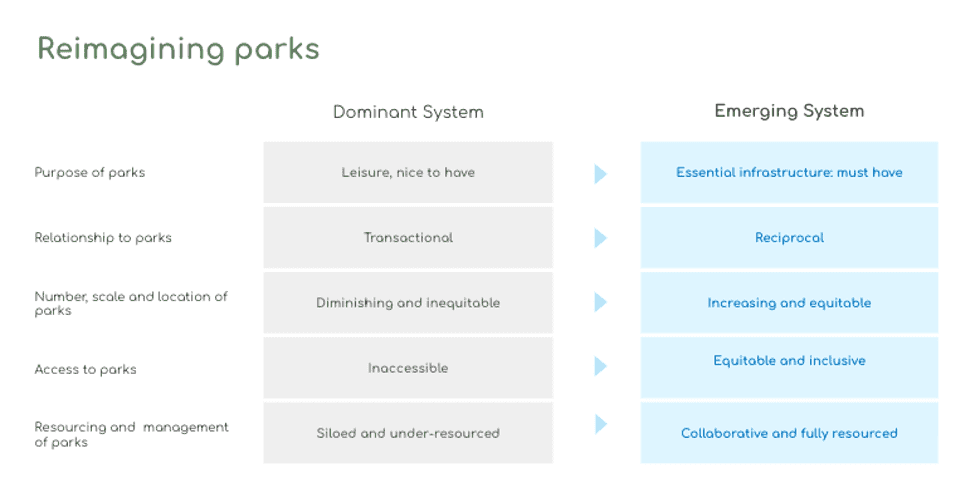

We identified the details of the “dominant system” and the “emerging system” of public parks. The concept of the dominant system helped us frame what needs to change. For example, the current system Park People works within is based on a narrow view of city parks as “nice to have” infrastructure for human leisure. In this system, parks don’t need to be equitably distributed or invested in, because we are not centring their transformative potential to advance human health and well-being, biodiversity, and climate resilience. This was a clear systems-level diagnosis of the current state, clearer than Park People had ever had before. The clarity was a game-changer.

Even more importantly, the two-loops model inspired Park People to articulate the future we want to help bring into being. As an organization where communications and storytelling have always been vital, this made immediate sense to us. Radical imagination – defined by Alex Khasnabish and Max Haiven as “the ability to imagine the world, life, and social institutions not as they are but as they could be” – is fundamental to systems change.

Making use of the tool: Applying the theory of change in the day-to-day

Park People has been living with our theory of change for about two years now. It has helped us to:

1. Build shared internal understanding of what we do

- The theory of change is enormously helpful in orienting new staff. But the dynamic runs both ways: new team members bring perspectives we didn’t have when we developed it and are able to poke and prod at the model with fresh eyes, sparking important conversations that help us continually refine our understanding of our impact.

2. Engage with partners and funders

- Conversations with prospective partners and funders now start from the common understanding that we are all actors operating in the same system. This is an empowering starting point that leans away from “What can you do for Park People and what can we do for you?” toward “What can we do together to drive systemic change?”

- The two-loops model illustrates the logic behind how Park People works as a national hub and interconnector. It has often been challenging to justify being a lower-profile “intermediary” organization that takes a more indirect path to impact than other types of non-profits. The theory of change helps demystify our work as an intermediary and situates our efforts to build the capacity of others (community groups, non-profits, park professionals) within a narrative of broader societal change.

- It is particularly useful when engaging with people in other sectors, from housing to climate action to mental health. For these folks, we need to explain what Park People does and the context we operate in at the same time. The model does both, and creates an opening for non-traditional park actors to see themselves in the park system.

3. Measure our impact across program areas

- As a non-profit without core funding, we are continually developing new projects and programs in response to needs and opportunities. Many new initiatives come with a set of metrics or intended impacts that are determined by the funder. Ten years in, we were quite good at evaluating the impact of specific projects but struggled to evaluate or communicate our broader impact as an organization.

- We mapped our core programs against the new theory of change and developed integrated measures that could be applied across programs and woven into new funding proposals. With fewer, deeper evaluation activities and integrated data collection rooted in data equity principles, we are coming into better alignment with our values of social equity and reciprocity, ensuring that our program designs are based on what we hear from the people we work with, not our assumptions about their needs.

Key learning for the social good sector

We wanted to share this process and example to inspire other organizations working for the social good. Here are some of our takeaways:

- Systems thinking is essential if you want to influence systems change. This can mean mapping out system actors, testing different system-change models against your group’s work (like the three models mentioned in this article or others), and identifying the system actors you most seek to influence and what change would look like for them.

- Name the new system, in detail, that you want to help bring about. So much of the time we see what’s not working, criticize, and push against outdated but powerful existing systems. That’s exhausting. Focusing on the vision of a truly healthy park system, or education system, or health system – whatever area you work in – is essential and energizing for this long-haul process of systems change. What does it look, sound, feel like? What are the policies and practices that become commonplace in this changed system?

- Invest time, energy, relationships, and money where aspects of this emergent system are already alive. There are pockets of change all around. They need resourcing to sustain and grow. Park People, for example, has connected and supported non-profits that work in large urban green spaces throughout the country, such as Vancouver’s Stanley Park or Montreal’s Mont Royal. This positioned them to support and measure their collective impact across the country and opened the door to collaborate with Parks Canada on the creation of new national urban parks.

- Get clear on your organization’s niche. Many organizations, especially younger ones, dabble in many types of activities until the diversity starts to be unwieldy. This is normal and natural as a learning process, but at a certain point organizations have to figure out what they do best and where they can best influence the system. Do you know why you are doing each program or activity? A theory of change or systems-change model provides a framework for making decisions about where to focus and which new opportunities to take on – or say no to.

- Theory of change does not have to be linear. If your theory of change is starting to feel like just another logic model, it may need renewal. Systems change is neither linear nor static, so maybe your theory of change doesn’t have to be either.

- Bring in critical friends to help figure all this out. Good consultants can be positive catalysts, whether in a young organization like Park People honing its purpose or in a more established organization in need of renewal. External support people can help team members say what they really need to say and transform frustration and muddled thinking into a sense of common, clear purpose. Consultants can introduce fresh ways of seeing an organization; offer tools, like the two-loops model; and create a process for structured, deep reflection that usually gets put off because of the day-to-day busy-ness.

Have you been engaged in systems thinking and change processes like ours? Do you know of other organizations that have taken inspiration from the two-loops model? We would love to connect! We believe that by sharing experiences, our sector’s capacity for systems thinking and systems change will grow stronger.