There’s a shortage of meal-delivery volunteers, writes Volunteer Toronto’s Joanne McKiernan. The reality of prioritizing basic needs in challenging times, she says, means we cannot rely on volunteers for the same types of roles, time commitments, or skills exchange as in the past.

There’s a shortage of meal-delivery volunteers. It isn’t a symptom of the pandemic; it’s a problem that’s been plaguing the sector for more than half a decade.

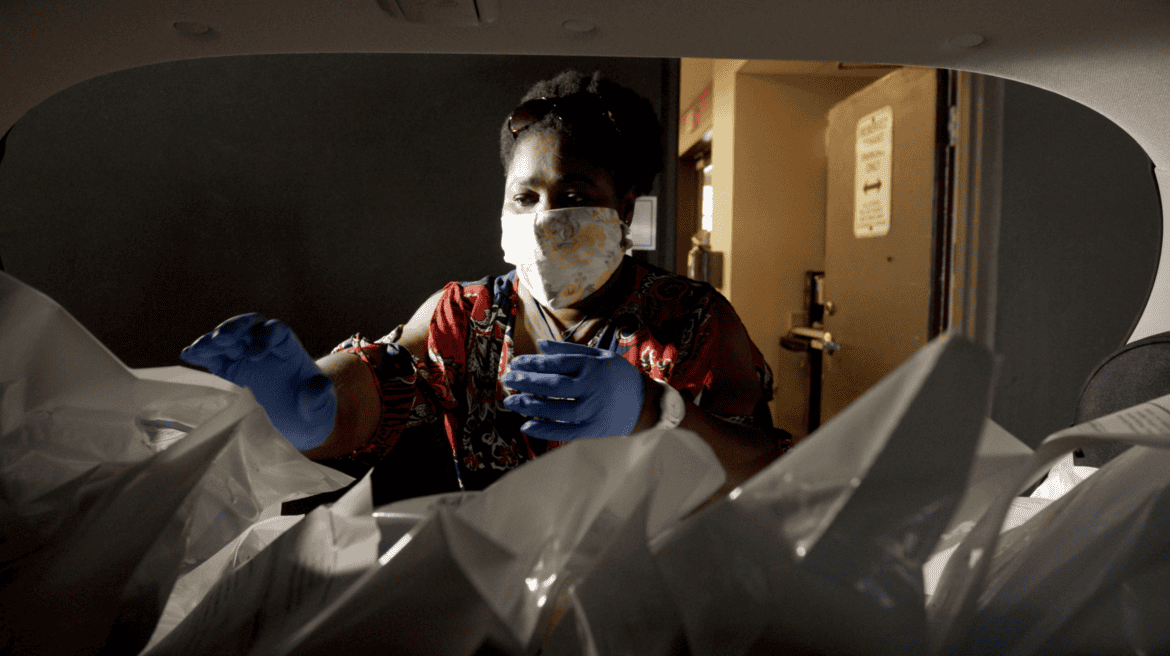

A few months ago, Volunteer Toronto received a call from a non-profit volunteer manager who was overwhelmed with the ongoing need to recruit volunteer drivers. There have been many similar conversations over the past five years, but this was different. The level of burnout and fear on this single person’s shoulders was agonizing. She can’t guarantee meals to clients without taking on the deliveries herself, and the weight of constant recruitment is despairing. Existing volunteers are saturated; the new ones rarely stay long. She cannot deliver all the meals herself or recruit all the volunteers she needs. How can she look to the future with hope? She doesn’t. And she’s not alone.

There are more than 20 Meals on Wheels programs, and a handful of grassroots groups, operating in Toronto that rely on volunteer drivers to deliver thousands of daily meals to isolated seniors and people with disabilities who cannot leave their homes. The volunteer driver role is notoriously hard to fill. We need an army of people who are available from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. with valid licences, cars, consistent time for unpaid labour, and the comfort and experience to drive in one of North America’s most congested cities. Sound impossible? It is.

There will never be enough volunteers to fill this need, and it’s time to acknowledge that as a society, we rely on volunteers for things we shouldn’t.

A service-delivery model reliant on volunteers

In 2020, Statistics Canada reported that supply of volunteers outstripped demand, with 52% of Canadians looking to volunteer waiting for non-profits to get back to them. At Volunteer Toronto, we were excited – could a spike in interest in volunteering finally mean that meal-delivery programs were flush with volunteer capacity? As essential programs supporting the call to shelter at home, meal deliveries were in high demand. We deployed projects to expedite matching for agencies, highlighted volunteer drivers as the most in-need role, and funnelled an incredible amount of interest to programs through a community response team. A hopeful push to test the hypothesis that we just needed more volunteer interest and availability, partnerships, and stewarding to solve the shortage issue. As you can probably guess, it didn’t work. It wasn’t enough. Interest didn’t translate into medium- to long-term labour for these agencies, and our interventions didn’t systemically change the funnel of volunteers adopting these roles. Through it all, one thing remained the same: very few can or want to be a volunteer driver, at least not reliably.

In an abundant volunteer recruitment landscape, the unpaid labour didn’t shake out. But you know what did? Funding to pay drivers. Amidst the pandemic, government funders saw the need for meals to get out the door, on the road, and into vulnerable people’s homes. We valued this labour by paying for it in multiple regions across Ontario. And in 2023 when we asked volunteer managers if they rely on paid staff for meal deliveries, two-thirds said yes, many holding the role of back-up driver themselves. Formal Meals on Wheels programs need to face a reality: they already pay drivers, but it is an unfairly masked addition to many volunteer managers’ job responsibilities.

The lines between paid and unpaid labour are already being blurred. Is it fair and decent for us to rely on volunteers and paid staff for the same roles? Where do we draw the line?

The bigger picture of volunteer shortages

The voluntary sector is at an inflection point. Within the first year of the pandemic, nearly one in two employed volunteer managers were dismissed, redeployed, or reduced in hours. Many programs outside of essential services were shut down, and eager volunteers were being turned away en masse. But recovery is well in motion in 2024, and lots of brand-new volunteer managers have been hired by agencies to bring volunteer programs back.

But the landscape has changed. Toronto Foundation reported in 2023 that the pandemic has accelerated a long-standing decline in friends-and-family networks, donations, and volunteering. People have less money, less availability, and less of an interest in formal volunteerism, especially when it means making a long-term commitment. The supply of volunteers and the reality of prioritizing basic needs in challenging times means we cannot rely on volunteers for the same types of roles, time commitments, or skills exchange as in the past. We cannot over-screen volunteers because the new generations of volunteers, racialized volunteers, and community members that need to prioritize paid work will not spend hours potentially retraumatizing themselves via police checks or proving that they are “fit” to give their time.

The supply of volunteers and the reality of prioritizing basic needs in challenging times means we cannot rely on volunteers for the same types of roles, time commitments, or skills exchange as in the past.

The Ontario Nonprofit Network’s latest State of the Sector report indicates that many non-profits are still reporting volunteer shortages and that there is a need for modernization in the sector. Yet as a volunteer centre, we’re hearing that potential volunteers are not hearing back regarding the roles they apply to, or that agencies are collecting information volunteers are not comfortable providing. The sector is used to looking for “easy” volunteers – the ones willing to comply with discriminatory and often unnecessary screening steps and who are privileged to work for free out of their own generosity, whenever and wherever they are needed. Volunteer shortages are the reported symptom, but the diagnosis of the problem goes much deeper in what activities we rely on paid or unpaid labour for, who we design those roles for, and how we exclude pools of volunteers through screening systems.

The sector is missing the mark on sustainability by replicating exploitative systems off the backs of vulnerable volunteers.

For meal deliveries, the “easy” volunteers were often seniors. But this, too, has dwindled with an aging population, increased health concerns when choosing volunteer roles, and transitioning from service providers to service users. The “easy” volunteer pool no longer exists, and with this comes an opportunity to rethink how and who should provide labour for essential service-delivery programs.

Why would a newcomer choose to volunteer for an activity in one space that is a paid activity in another space? And when do we call it exploitation?

Federal immigration targets will also challenge old systems and ways of being. The government tells new immigrants to volunteer for Canadian experience and references on their pathway to securing a job. More than half the participants in Volunteer Toronto’s volunteer programs in 2023 have been in Canada for less than one year. This means many diverse volunteers in vulnerable economic, housing, and food security positions are entering an exhausted voluntary environment at the government’s direction. They’re navigating what is fair use of their labour and time and bridging the gap between what civic engagement means in their own cultural contexts compared to how we rely on unpaid labour in Canada. Why would a newcomer choose to volunteer for an activity in one space that is a paid activity in another space? And when do we call it exploitation?

What are decent roles for volunteers?

There isn’t a checklist for evading exploitation under a banner of volunteerism. What complicates things further is that almost every non-profit and charity starts as a group of civically engaged residents looking to fill a gap or create a new space. People go unpaid while doing this work for years before forming something that should be accountable to decent-work and decent-volunteerism values. Each program and organization will be unique in reflecting on what is fair and sustainable labour.

Agencies can start by diagnosing volunteer shortages. Ask, how do outside factors, such as immigration growth and economic pressures, affect how people give time in your context? And how do your recruitment and screening processes harm and exclude community?

Investigate the relationship between paid and unpaid labour in your organization. Ask, where do roles overlap and who fills service-delivery gaps? And how often do you rely on paid labour as a backup for volunteer responsibilities?

A systemic shortage of volunteers should not be the reason people can’t get the meals they need.

Critique your organization’s philosophy on funding volunteer engagement. Ask, are leaders of volunteers paid a decent wage? What expertise is valued financially or expected to be given as free labour? And is it sustainable to rely on volunteers, especially for essential programs?

A systemic shortage of volunteers should not be the reason people can’t get the meals they need. If we’re looking at the next month, year, or five, 10, 20 years of volunteer motivation and demographic trajectories, the data isn’t promising. We’re not going to recruit enough volunteer drivers, so we shouldn’t pretend things will get better. A volunteer-driven service model no longer meets the needs. It’s outmoded, especially in an urban community like Toronto, where there are more challenges in completing the task of driving. Which is more than a task: it’s often the only food on someone’s plate and a safety check when no one else checks in.

Volunteer Toronto accepts that there are two potential fates ahead for Meals on Wheels programs powered by volunteer drivers: we will feed fewer people as volunteer shortages continue, burning out our volunteer managers, or we will prioritize systems change to feed people sustainably by advocating with funders to pay for driver labour. Systems change starts by having difficult conversations within and across our organizations and communities.

We must listen to volunteer managers who are incredibly burnt out and reframe meal-delivery volunteer shortages as systemic when speaking with funders.

I’ll leave you with a bit of hope in the power of us working together to overcome systemic challenges: a world where volunteers aren’t relied on for essential services is one where volunteers still hold an essential role. Volunteering is an access point to building empathy and understanding across communities. Volunteering can be an access point to self-actualization, to meaning, to health, and to community-making. And now is the best time to start on a path toward decent volunteering for all.