The lessons emerging from the work of the Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Collaborative – about collaboration, relationships, and learning to be a good helper – “can and should be adopted by all of philanthropy.”

Northern Manitoba is home to the Anishinaabe, Anishininiwak, Ininiwak, Nehethowuk, Denésuliné, and Inuit Peoples, and it is part of the homeland of the Red River Métis. It is a place where land and culture are deeply intertwined. Spanning nearly 80% of Manitoba’s land mass, this vast region is dotted with many small, remote Indigenous communities.

“Each community is extremely unique in its traditions, cultures, geography,” says Tasha Monkman, who grew up in Pine Dock, a small fishing community on the shore of Lake Winnipeg. “We also share a lot of similarities in terms of our challenges and successes. Northern communities are really rich in their traditions.” Monkman is a member of Fisher River Cree Nation. Her ancestors have a long history in the Lake Winnipeg narrows, she says, “a history I’m proud of.”

Many of Northern Manitoba’s small towns and communities, like the one Monkman grew up in, have a strong sense of determination but face common challenges relating to their services and infrastructure. Monkman’s hometown had a post office, a fish processing plant, and a community office. But for most basic necessities, like grocery stores and healthcare, she had to leave her community. “A lot of communities face similar challenges in that regard,” she says. Although it can be tough, “there’s still so much beauty.”

As communities in Northern Manitoba work to rebuild self-sufficiency and strengthen their local food systems, well-being, and culture, philanthropy is learning to show up in new ways and offer support that is respectful, responsive, and rooted in relationship. The lessons emerging from this work reach far beyond the region.

‘The system wasn’t working’

Despite the many strengths, needs, and opportunities in Northern Manitoba, it received very little philanthropic support for many years. In 2014, approximately 3% of all philanthropy in Canada went to Manitoba, and almost none of it ended up in northern communities. “All of these organizations wanted to fund Indigenous work, but there were no grants going to Manitoba,” explains Julie Price, who worked for an organization funding food-security initiatives in the province. “For northern Indigenous communities, the system wasn’t working.”

Price describes how funders would travel long distances to visit communities, only to leave the same day without taking the time to listen, understand local needs, or build trust. Each visit required community members to take time to host and educate funders, many of whom ultimately never provided any funding. It felt extractive, and communities were frustrated.

Moreover, funding application processes were often inaccessible and misaligned with community needs. Funders expected communities to have “qualified donee” status (which few held), strong English writing skills, reliable internet access, and the capacity to complete complex, standardized application and reporting forms. Communities had to compete against large organizations that employ professional grant writers, and their work often had to fit into narrow categories defined by the funders’ priorities. These are precisely the kinds of barriers that the trust-based philanthropy movement has been calling out in recent years.

Funders had the money, and they wanted to fund the work, but they didn’t understand the gap between them and communities.

Julie Price, Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Collaborative

These funding requirements overlook the lived realities of many Indigenous communities and the interconnected nature of their work, where food security, youth well-being, language revitalization, and land stewardship are deeply interwoven. The barriers that communities in Northern Manitoba face reflect a broader pattern. Across the country, Indigenous organizations consistently face funding inequities. They receive less than 1% of all charitable funding and must navigate systems shaped by colonial assumptions and structures.

“Funders had the money, and they wanted to fund the work, but they didn’t understand the gap between them and communities,” Price says. “And communities were so tired.”

There had to be a better way.

A collaborative approach

In 2013, Price helped launch a pilot funding initiative rooted in community-defined principles of what makes a good helper and partner. “[Communities] wanted a highly relational approach where they could see the faces of the humans they are working with and systems that were culturally appropriate,” she says. Communities also wanted funders to work together and learn from one another. This way, communities wouldn’t need to spend time engaging with and educating each funder individually.

[Communities] wanted a highly relational approach where they could see the faces of the humans they are working with and systems that were culturally appropriate.

Julie Price

Three funders (called “collaborators”) contributed to a pooled fund that supported community-led projects focused on food sovereignty, cultural resurgence, and community building. The granting process was collaborative, with decisions made by consensus and guided by northern community members. While an evaluation of the pilot described the granting process and decision-making as “inefficient,” community partners strongly supported the approach and expressed a desire to see it continue.

In response, the Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Collaborative (NMFCCC) was launched in 2014. Guided by a group of “Northern Advisors,” the initiative joined its host organization, MakeWay, welcomed a fourth collaborator, and entered another year of grantmaking. With a $100,000 budget, the collaborative supported a wide range of community projects – from horticulture and beekeeping to chicken coops, greenhouses, and traditional food programs that reconnect people with country foods.

What began as a modest pilot has evolved into a powerful model of philanthropy. Today, the NMFCCC includes 14 collaborators and has granted more than $7 million to 76 community partners.

The granting process begins with conversation and relationship building – not a funding application. If staff determine that a project is a good fit, they help the community move forward with a funding request, either through a written or oral proposal. There’s a peer review process, where northern people review proposals to provide feedback, context, and ideas. Then, a granting committee made up of collaborators, staff, northern advisors, and northern people review the proposal. If the committee has questions or concerns about the proposal, the applicant has an opportunity to update it.

Most of the organizations that have received funding from the collaborative have never been part of a charitable partnership before. But because the granting process is built to be inclusive and supportive of northern communities, more resources reach more communities. In the end, almost every project that applies receives funding. In 2024, granting committees approved 40 of 42 applications. The remaining two applications required more conversation with the applicants before a decision was made, but both were ultimately approved.

Working slowly and relationally

Monkman was introduced to NMFCCC while working as the community administrative officer for Matheson Island, near Pine Dock. As part of her role, she wrote grant applications for local projects and in 2020 secured funding from the collaborative for community garden boxes.

It was during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic that Monkman received the funding, and she had a hard time sourcing materials because of supply chain issues. She was worried about how the challenges would affect her funding, but NMFCCC was understanding. “That flexibility, and their help looking into solutions – they provided so much support. I thought it was unusual. Once you get a grant, there’s usually no more communicating between funder and community,” she says.

Matheson Island built a garden box for each of its 30 households, and Monkman’s positive experience with the collaborative left a lasting impression. “They were working in this way that I had never worked with folks before,” she says. When a job opportunity came up with NMFCCC in 2023, she immediately applied.

Monkman is now one of six coordinators, or what she calls “relationship leads,” for the collaborative. Describing the role, she says, “It’s our job to keep a good line of communication, checking in with people, offering our support.”

They provided so much support. I thought it was unusual. Once you get a grant, there’s usually no more communicating between funder and community.

Tasha Monkman, NMFCCC

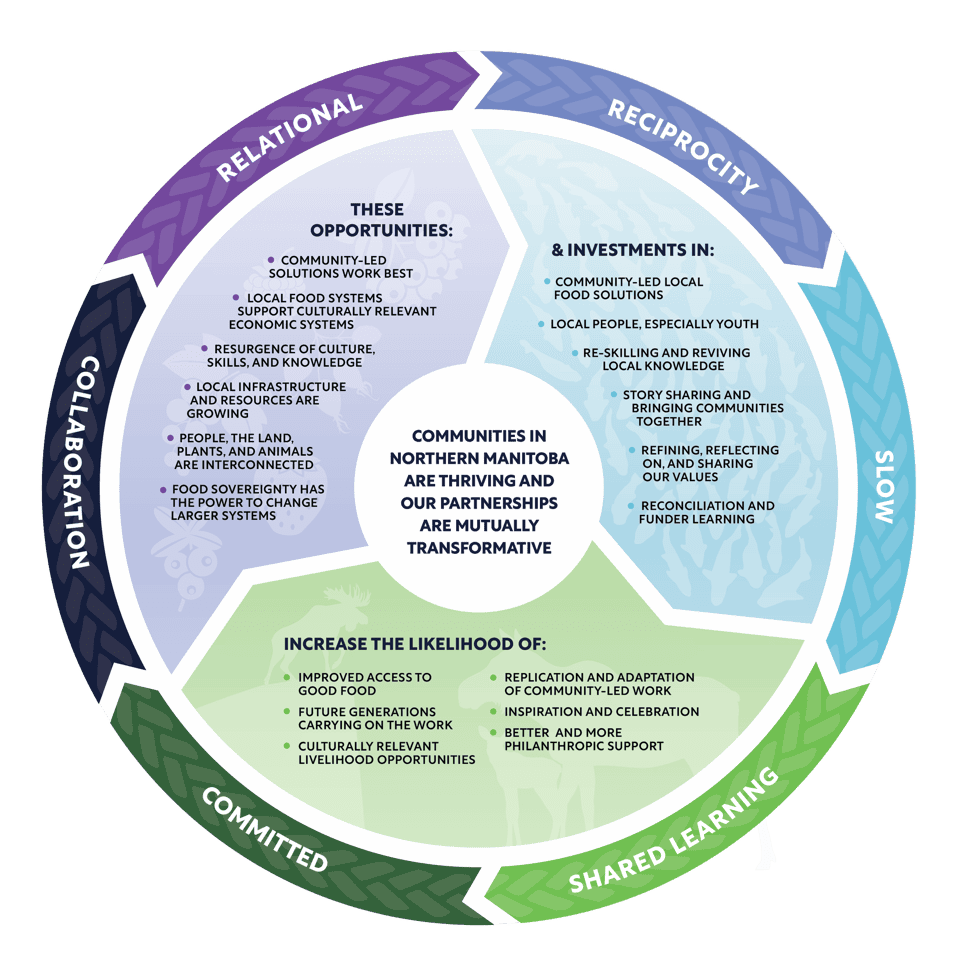

NMFCCC is guided by six values, including a commitment to working in relationship and slowly – an intentional rejection of the urgency culture that is common in the charitable and non-profit sector, and a practice that is essential for building trust. “Each relationship is unique,” Monkman says. “We take the time to show that we care and want to get to know you and your community.” Instead of pushing into communities, it means waiting to be invited in and allowing relationships to form and align over time.

Monkman recently built a relationship with Little Grand Rapids, a fly-in community near the Manitoba–Ontario border, where a resourceful community member was working to expand a garden that she had built using locally sourced tools and materials. This community member, Naomi, shares her harvest with neighbours who have come to rely on the garden as a vital source of fresh produce.

Getting funds to community partners, like Naomi, who may not have charitable status and live in remote locations often calls for creative solutions. In these situations, staff work closely with community partners to figure out how to administer funds and help them get projects up and running. “I literally hit the ground running and went to the store, where I purchased the tiller, seeds, and tools she needed,” Monkman recalls. “I loaded it all in a truck and delivered it to a local airline to be flown into the community. Naomi was thrilled when the supplies arrived in her community.”

Learning to be a good helper

The emphasis on relationships and support that guides how staff like Monkman work with community partners is also reflected in how collaborators are expected to engage. NMFCCC challenges the typical funder–grantee dynamic where the funder provides a grant, the grantee completes the work and submits a report, and communication ends until the next funding cycle. Instead, NMFCCC tries to foster genuine, long-term relationships between collaborators and community partners, supporting collaborators to be “good helpers” both within and beyond the collaborative.

But what does it mean to be a good helper? As Price notes, in Northern Manitoba it means working relationally and designing systems that are culturally appropriate. It also means setting aside funders’ priorities to centre the needs, knowledge, and leadership of communities. For NMFCCC, this happens naturally through its collaborative funding model, which asks funders to release ownership and control over how their resources are allocated. It also means understanding the history and ongoing impacts of colonialism and approaching relationships with respect and care.

For those outside of NMFCCC, there are concrete practices to take inspiration from: offering wraparound support through introductions to other funders, demonstrating care by checking in regularly, and eliminating lengthy reporting requirements.

NMFCCC’s way of working is new for many collaborators. In addition, most come in with little or no experience in the region, which adds another important layer of learning. That’s why funder learning and unlearning is a core priority within the collaborative. A key part of the work involves supporting collaborators to unlearn old habits and embrace new ways of supporting communities, which are then carried back to their own organizations. Staff and northern advisors help steward this process, acting as a bridge between funders and communities to build trust, strengthen relationships, and reduce the risk of harm. “What people thought they knew – we’re trying to tell them it doesn’t have to be like that; we’re trying to be more community focused,” Monkman says.

The learning trips can be challenging and life-changing . . . It hits people on a professional and personal level.

Tasha Monkman

Some of the most meaningful learning happens during community-hosted learning trips. Monkman says that “the learning trips can be challenging and life-changing. They’re visiting, learning, and immersed in the way of life, traditions, and challenges. It hits people on a professional and personal level.”

Omar Elsharkawy, research and policy specialist at MakeWay, had the chance to attend a recent learning trip to Norway House Cree Nation. Participants took part in a sweat lodge, hikes to locally significant areas, and visits to community projects. “Meeting other collaborators and community members was really wonderful, and I learned so much from so many different people,” Elsharkawy says. “The level of connection and friendship between community members, staff, and collaborators – it’s different than anything I have ever seen in philanthropy.”

Ripple effects

Alongside supporting powerful, community-led work, NMFCCC is also having a meaningful influence on the philanthropic sector. In his research role at MakeWay, Elsharkawy recently authored a report exploring how participating in NMFCCC has influenced collaborator organizations.

Interviewees shared how their participation has shaped their approaches to granting, decision-making, relationships, and their ongoing commitment to reconciliation. Specific changes include adopting consensus-based decision-making, simplifying application processes, and offering longer-term, more flexible funding agreements. One collaborator quoted in Elsharkawy’s report said they “can’t conceive of doing grantmaking any other way now.” Many have also redirected significantly more of their funding to Indigenous-led organizations, including through endowment transfers.

What surprised Elsharkawy most in his interviews with collaborators, however, were the profound personal impacts that participating in NMFCCC has had on them. Several shared that being part of the collaborative had truly changed their lives. “That shows how successful the approach is,” he says.

Despite the geographic focus and context of the NMFCCC, the values they adopt and practice can and should be adopted by all of philanthropy.

Omar Elsharkawy, MakeWay

Both Monkman and Elsharkawy believe that NMFCCC’s practices can be adopted by other organizations working in the sector. “Despite the geographic focus and context of the NMFCCC, the values they adopt and practice can and should be adopted by all of philanthropy,” Elsharkawy says. Monkman agrees and encourages others in philanthropy to consider its relational way of working. “Taking time to build meaningful relationships that go beyond the timelines of granting periods – there’s so much to learn from communities,” she says.

While the collaborative is having a ripple effect across the philanthropic sector in Canada, it remains grounded in the visions and opportunities within Northern Manitoba. “We all understand the challenges and the beauty and how amazing it is to live here,” Monkman says. NMFCCC shows that philanthropy can truly support communities when it shows up with commitment, curiosity, and a willingness to adapt. As Monkman puts it, “If there is a willingness for people to want to learn and want to make changes in this sector and space, it’s possible. I’ve seen it.”