The Kickback Foundation’s vision is to create worlds and opportunities where kids have the space and support they need to explore their own journeys and define themselves – using sneakers as a magnet.

What does it take to open up opportunity? For 16-year-old Abdul Hussein, it was a pair of sneakers.

One day, Hussein’s mom told him that Kickback was hosting a sneaker giveaway. He went, because who doesn’t want free shoes? A mentor from his former after-school program was there, and they reconnected. The mentor told him about Kickback’s Run Club, and he joined.

A while later, his mentor said, “Hey, do you want to run the Chicago Marathon?” Hussein said yes. “A model that I go by is that you first say yes to a challenge that confronts you, and then you figure out the how after,” he says. Hussein ran the 2024 Chicago Marathon in four hours, with his mentor by his side. Now he’s training for the Toronto Waterfront Marathon – in new shoes, of course.

A model that I go by is that you first say yes to a challenge that confronts you, and then you figure out the how after.

Abdul Hussein, Kickback participant

“Ever since I came to Canada [from Eritrea] in grade 1, I’ve always desired to feel seen. You know what I mean? And I think that’s a common feeling,” Hussein says. “There might be a misconception that kids’ dreams are limited because of where their family financials are.”

Sneakers loom large in pop culture. From the moment Jesse Owens stepped onto the Olympic track in 1936 in a pair of custom sneakers by Adidas founder Adi Dassler, to the first Air Jordans that came on the scene in 1984, kicks have defined personal style and stood for belonging and possibility. But when you’re a kid whose feet are growing faster than your family’s bank account, sneakers and everything they represent can feel impossibly out of reach – and can make the world feel like a place you can’t step into in the way you want.

“Kickback started when I wanted something for myself and I couldn’t have it. My mom told me if she bought me new shoes, then she wouldn’t be able to buy me groceries,” says Jamal Burger, 31, a photographer and filmmaker and the founder of The Kickback Foundation, a non-profit based in Toronto’s Regent Park and Moss Park that has distributed more than 8,000 pairs of sneakers worldwide. “So many kids have been in situations where all we want to do is find a way to become successful as ourselves, but because of the environment, the schools we attend, and the lack of resources that they have, we can’t reach for what we want.”

According to Social Planning Toronto’s Fighting for Our Future: Child and Family Poverty Report Card, Toronto 2024, between 2020 and 2022 the child poverty rate in Toronto increased from 16.8% to 25.3%. Racialized children had a poverty rate of 17.8%, nearly double the poverty rate of non-racialized children. The rise mirrors a similar increase in provincial and national rates. While the federal Canada child benefit contributed to a reduction in child poverty between 2016 and 2019, many of those gains were erased during the pandemic.

That’s hundreds of thousands of kids whose parents choose between buying food and sneakers. Who are told “no” more than “yes.” Who every day receive messages that they’re not worthy, and have to worry about not stepping on the wrong side of the many visible and invisible lines that can determine the paths of their lives.

The weight of expectations that racialized youth face pile on to the structural inequities, a reality that Trinidadian-Canadian poet and writer Ian Williams described in a 2024 interview in which he recalled meeting a young girl at an event. “There are all these expectations of how to be Black. But what I’m more interested in from that girl is ‘Do you like unicorns?’ You don’t have to take this freight on you for your identity. You can have the kind of freedom to be nerdy and fascinated about things.”

All kids want to express themselves. So what I realized is that if I could gather shoes, I could gather youth. And if I could gather youth, what could I offer them?

Jamal Burger, Kickback

Burger’s journey started with an obsession with basketball and sneakers. That led him to an interest in photography. He started an Instagram account where he posted his photos of sneakers. The owner of Livestock, a national sneaker retailer, noticed and asked if Burger would like to work for the company. Burger didn’t own a camera, so they made a deal: the owner would buy him a camera, and Burger would pay it off by photographing kicks for the company’s website. Soon, the brands whose shoes he coveted as a kid were sending him free samples. “I just thought it was the stupidest thing in the world because I was, like, how come no one was giving me and my friend sneakers when we were kids?” he says. He recalls being on set shooting a campaign with paid actors, thinking, “This is a waste of money because there could be community at the heart of these stories. People could care so much more about what gets put on television, what gets put into the media.”

Organizing sneaker drives has evolved to a number of sports- and arts-based programs, including weekly run clubs led by community mentors that have rallied close to 100 runners, girls’ basketball sessions, a Youth Ambassador program, and the Reframe program, which uses film to spark conversations about predominant cultural narratives and the power of creativity and the arts to rewrite them. For Burger, working with youth is about creating opportunities for them to step into the places they belong. Sneakers are the magnet. But the vision is to create worlds where kids aren’t defined by the words and narratives that others use to describe them – where they have the space and support they need to explore their own journeys and define themselves.

“All kids want to express themselves,” Burger says. “So what I realized is that if I could gather shoes, I could gather youth. And if I could gather youth, what could I offer them?” What Kickback does is open up spaces that offer kids transformative experiences that are barriered or inaccessible to them, and challenge the way youth are represented in and by mass culture. The foundation reached 2,000 youth in Toronto last year, supported by a roster of financial and in-kind partners that includes Arc’teryx, Asics, and the City of Toronto.

Libin Ahmed, 23, joined the Reframe program in 2024 after following Kickback on Instagram for a while. “I already knew I was a little bit in over my head because we went around the room telling the group what our favourite movie was. I said Spider-Man, and everyone else was saying, like, black-and-white movies from the ’70s,” she says with a laugh. The group watched Soleil Ô, an experimental film about colonialism, immigration, and exclusion by Mauritanian-French director Med Hondo. It was nothing like anything Ahmed had ever seen. Lauren Cramer, an assistant professor in the University of Toronto’s Cinema Studies Institute who focuses on Blackness, aesthetics, and popular culture, led a discussion after the film. Ahmed describes the experience as a profound perspective shift. The lesson she took away is that anything is possible through art.

I think the biggest thing about Kickback for me is that I had that experience to try something new and then succeed in it.

Libin Ahmed, Kickback participant

Ahmed applied what she learned in a short film she made in the program that challenges popular representations of cowboy culture. “Just the fact that I was able to do that, and it was something that I had been thinking about for months and I actually got to finalize, it was insane. Like, I didn’t think I’d actually get that far, and then I did.”

Through another program, Being Black in Canada, Ahmed made a documentary called My Neighbour Taybah, about her experience building a relationship and connection with her older female Somali neighbour through shared explorations of Toronto. The film screened at the Toronto Black Film Festival. “I think the biggest thing about Kickback for me is that I had that experience to try something new and then succeed in it,” Ahmed says. “Now I’m very frantic in my own life thinking, ‘Well, what else have I always wanted to do that I can do?’”

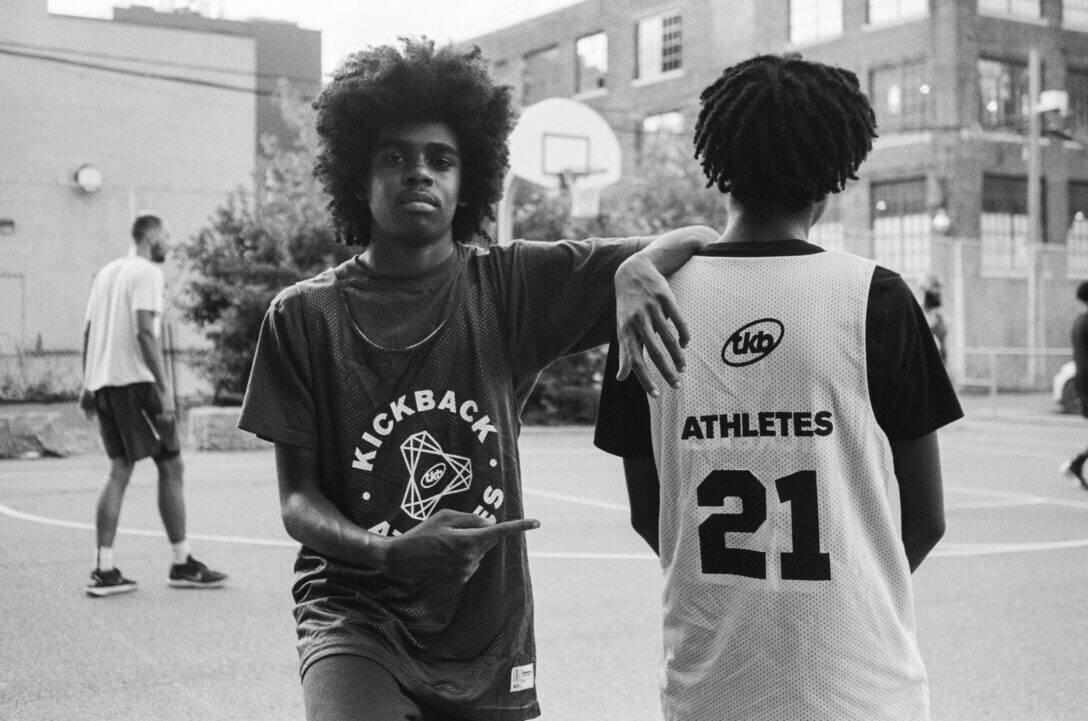

In contrast to some children’s charities, Kickback leans heavily into positive messaging and imagery. Burger’s lens captures youth as equals, showing them in their moments of possibility instead of as potential recipients of support. It’s how he wishes he and his friends had been seen by the adults in their lives.

“I fundamentally think giving back is like an equal exchange,” Burger says. “What bothers me is when I get a newsletter and there’s a kid sitting in an alleyway and the photo is black-and-white or sepia-toned, and it’s like, look at poor John – if you don’t donate today, he won’t have anywhere to sleep this Christmas. That stuff doesn’t work for me. I think we should be challenging this voyeuristic lens on philanthropy because the kids who are experiencing that aren’t going to step up and say, ‘I need help,’ because they see how the people with money sometimes describe them.”

Delsin Holder, 19, is a writer and spoken-word poet who joined Kickback’s Youth Ambassadors cohort – a 12-week program that gives youth tools to actualize the change they want to see in their lives and communities. Holder speaks in a poetic syntax that conveys a unique perspective on the world. He joined the program after a few years playing high-school basketball in Toronto, Florida, and Texas.

Shoes brought us here, and we as a collective are ready to leave footprints that shake up the world for generations.

Delsin Holder, Kickback participant

Holder describes his experience in Texas as an ordeal, in part because of the deep-rooted racism he observed there. He came back to Toronto feeling untethered. He’d been involved with Kickback before and he re-engaged because he felt at home there. He joined the Youth Ambassadors program even though he didn’t feel like he qualified, and his confidence issues made it tough to stick around. But he did it. Then he was chosen as the valedictorian. In his speech he said, “Shoes brought us here, and we as a collective are ready to leave footprints that shake up the world for generations.” He’s now looking ahead at university, and he voted for the first time in the 2025 provincial election.

While the Kickback community is strong, Burger worries about the future. “A lot of the funds that became available when Black Lives Matter happened and the need to support Black communities became a hot topic is being dialled back,” he says. Corporate donations are also more difficult to access. “It’s unfortunate because what we’re doing has momentum, and I want to continue to build on it.”

For Ahmed and her peers, it’s existential. “When you’re treated like you are somebody, then you believe that you’re somebody.”