Toronto Foundation and the Toronto Aboriginal Support Services Council partnered to regrant funds to Indigenous organizations – with the foundation ceding full control over designing and delivering the grant program to TASSC.

There is a lot of conversation in philanthropy and other spaces about decolonizing, but there’s little agreement on what it really means. “I hear the word ‘decolonize’ a lot,” says Lindsay (Swooping Hawk) Kretschmer, the executive director of Toronto Aboriginal Support Services Council (TASSC), a non-profit that addresses the social determinants of health to improve the socio-economic and cultural well-being of Indigenous people in Toronto. “I don’t know what that word means or how it actually applies in a colonial setting, but I do know that if you change hearts and minds, you change humans. And it’s humans who build systems and uphold them and maintain them, so we have to change hearts and minds. I think we have to move from apathy to empathy to greater awareness and understanding.”

Mohamed Huque, director of community impact at the Toronto Foundation, agrees that the notion of decolonizing philanthropy is ambiguous, but something he and the foundation did in that spirit and intention was to collaborate with Kretschmer and TASSC and initiate a regranting program to more effectively direct resources to Indigenous organizations in the Toronto area. Regranting is a practice where funds flow from a funder through an organization that is not typically a funding organization but has specialized knowledge and relationships to support the deployment of funds. TASSC’s partner organizations address housing, legal, employment, health, education, and cultural needs; funding became part of the work only during the pandemic.

Early relationship-building and advocacy for funding parity

Kretschmer has worked in the non-profit sector for more than two decades at the local, provincial, and national levels in senior leadership roles, primarily in Indigenous organizations. Born in Toronto and raised as an urban Indigenous person, she’s Mohawk and German and her family is registered to Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. She first initiated conversations with Toronto Foundation about its Indigenous funding practices a number of years ago after seeing funding flowing to an out-of-province group operating in the area. “If we look across the funding landscape, municipally, here in Toronto, most Indigenous organizations received between zero and 1% of the funding totality across sectors, be it government, private, and philanthropic,” she recalls. “We were advocating for greater parity, greater access, and that sort of universal funding to all agencies, which they’ve since managed to, in a very short time, achieve through their various efforts.”

Those early conversations developed into the strong relationship the organizations enjoy today, which allowed TASSC to regrant on behalf of the foundation, creating greater access to funds for Toronto-based Indigenous organizations. Toronto Foundation’s funds are primarily designated through staff, donor, and community input. The foundation realized that TASSC, an organization that had long-standing relationships with its members and in community, would be able to better reach Indigenous organizations and bridge gaps – allowing the foundation to create more impact by ceding power and control.

Overcoming funding barriers

Indigenous organizations have traditionally faced barriers in accessing funding, something Kretschmer attributes to, in some cases, lower priority based on population size, lack of or ineffective outreach, and laborious or irrelevant application and reporting procedures that aren’t reflective of their needs. “I’ve seen so many program budgets throughout my career, over the last 20 years, and one thing that I see in common with all of them is – let’s say you get a government grant that’s for the program, the salary, the benefits, the administration. Those are typical line items. You’ll never see in there a line item for culture, for land, for language. We’re expected to use funding from our program line item to do that. Yet no other agency has that unique need that we often have that’s central and core to our program delivery and design across the board. I think program funding has to transform. I think we need to move away from these prescriptive transactional relationships to a place of meaning, to a place of purpose, where we understand each other at a human-to-human level. That involves coming together, getting to know each other: who are the personalities, who are the players, what are the nuances and the histories and all these other things that make up what we are as a community, as an entity, to truly understand and appreciate the work we do.”

I think we need to move away from these prescriptive transactional relationships to a place . . . where we understand each other at a human-to-human level.

Lindsay (Swooping Hawk) Kretschmer, Toronto Aboriginal Support Services Council

Toronto Foundation staff, when reflecting on the success of the regranting initiative, speak to the strength of the relationship with TASSC as foundational to its success, a sentiment Kretschmer echoes. “Human nature supersedes process by country mile, right? It sometimes relies on the good hearts and good minds of just a select few groups of people that are going to come together to make that magic. I think we were fortunate – right time, right place, right people – with respect to our two entities coming together.”

Changing processes to create change

Kretschmer recalls how in the early days of the pandemic Toronto Foundation was one of the first funders to step in and offer assistance. Unprecedented times gave rise to unprecedented processes, and the two negotiated a different way of doing things that made more sense. “We recognize they can’t compromise on certain accountabilities, but they’ve also been willing and flexible to modify systems, practices, and approaches to make funding and granting more accessible, more meaningful, and more measurable,” she explains.

Kretschmer recalls how other funders took notice of the foundation’s innovative approach. “They saw that they were creating space for self-determination and funding, too, which was a foreign concept,” she says. “We were so used to this prescriptive way of doing things. Here was the Toronto Foundation saying, ‘No, let’s try something different. We’re willing to say, “Look, let your communities decide, at a local level, independently, how they need to respond to the pandemic.”’ We were in unprecedented times, and what we saw was tremendous outcome and results as a result of being able to have that self-determination without compromise to those accountabilities like audits, reporting feedback on the impact and the outcomes associated. I want to say that they’ve been innovative, flexible, supportive, and consistent.”

Other funders saw that [Toronto Foundation was] creating space for self-determination and funding, too, which was a foreign concept.

Lindsay (Swooping Hawk) Kretschmer

“In a lot of cases with foundations, you repeat conventional practices,” Huque says. “But we wanted to try something different, not because we were trying to be innovative but because there are more equitable ways to do this. We were fortunate to have the relationship with TASSC.” He describes Kretschmer as a “fierce advocate for her community” leading an organization that was well-positioned to do this work. In reflecting on regranting programs’ best practices, Huque recommends that foundations ensure that they share infrastructure as needed with regranting partners and that these programs get set up in a way that doesn’t derail partners from their missions. The regranting program needs to be something that the partner sees as core to what they are doing rather than something that is distracting or detracting from their purpose, he suggests.

Small grants, big results

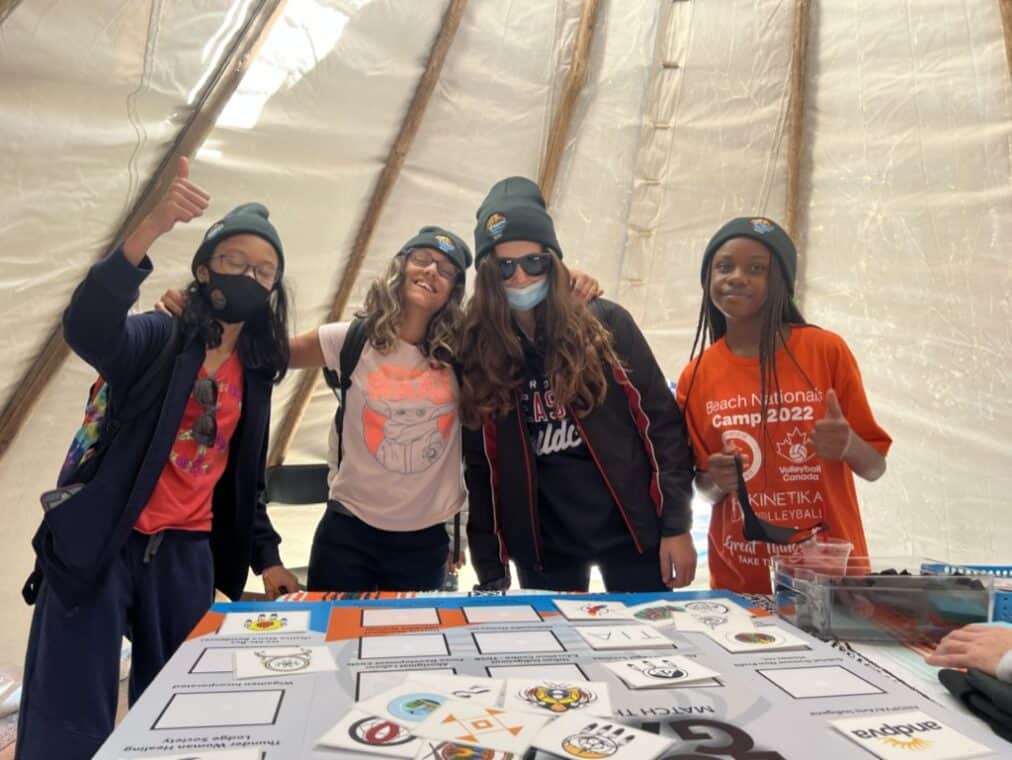

One of the strengths of TASSC’s regranting program is its microgrants. To create equal access and to support self-determination, it implemented a community-basket approach, reflecting the philosophy “Take what you need, leave what you don’t.” This approach recognized the power and impact of small organizations and had some exciting results for those groups.

It blossomed into this beautiful thing where agencies, regardless of shape or size, were able to do some pretty tremendous work out there in the world.

Lindsay (Swooping Hawk) Kretschmer

“What we saw in our funding-spending trends in year one and two were some of the smallest organizations at our table had the biggest impact in terms of spending. It was actually phenomenal to see. What it also did for them was it put some of them who were smaller or lesser known on the map to become now recipients for larger funding envelopes and entitlements they hadn’t had historically, and they grew substantially as a result. This actually contributed to significant growth within our sector,” Kretschmer says. “We were really just going into it with a lot of philosophical ideology about how good this is going to work, and how great it is to follow these traditional concepts and let folks do what they need to do without too many restrictions. It blossomed into this beautiful thing where agencies, regardless of shape or size, were able to do some pretty tremendous work out there in the world.”

Through greater access to funds with fewer restrictions, Kretschmer saw more innovation. “We were not as restricted as we’ve been trained or conditioned to believe ourselves to be. I think what we saw was creativity, innovation, love, and care for the community in ways that were genuine and supportive and collaborative too. We were coming together collectively as not only Indigenous organizations but with our allies and stakeholders like the Toronto Foundation – its team, its employees, its board – to do some really good work together,” she says. “You can have self-determination without compromise to accountability structures, and you can have funding relationships that go beyond reporting tools to a place of humanity and human-to-human, spirit-to-spirit connection that take us deeper into our collective awareness, and understanding what it is we actually do out there in the world and why it’s so important.”

Building relationships for the future

Sharing those stories of success with sensitivity can be challenging waters to navigate, but Kretschmer has been impressed with how that has looked so far. “I think Toronto Foundation has been exemplary in terms of always checking in, always being mindful, really honouring and upholding notions of co-development and ‘nothing about us without us’ principles and practices in a way that’s very tangible and meaningful,” she says. “It’s not about checking a box for them. It’s about meaningful relationships with our community and getting to know us and understand us.”

Looking to the future, Kretschmer is optimistic that collaboration like this with Toronto Foundation will continue, grow, and evolve, but she also hopes that other funders will follow suit in creating more meaningful funding opportunities that benefit Indigenous communities and organizations. She also hopes that they join her in exploring “how do we put our heads together across different sectors, to work in collaboration, to reimagine the funding landscape going into the future?” and that they take the time to learn and prepare themselves to work effectively with Indigenous organizations.

We still have these accountability mechanisms in place. It simply means that we are self-determining the ways in which we’re doing things that matter for our communities and have meaning, merit, and impact.

Lindsay (Swooping Hawk) Kretschmer

Kretschmer wants to encourage confidence in Toronto Foundation’s approach and inspire similar initiatives. “I think [funders] need to know that self-determination and flexible funding doesn’t mean a free-for-all or ‘go away and spend your money irresponsibly’ and not care; it’s taking responsibility for the resources,” she says. “We still have these accountability mechanisms in place. It simply means that we are self-determining the ways in which we’re doing things that matter for our communities and have meaning, merit, and impact, as opposed to colonial approaches that don’t work for us. Never have. They’re never going to. We need to be given the space and freedom to do these things from a culturally appropriate Indigenous lens,” she emphasizes. “That line that ‘we’ve always done it this way’ – it doesn’t work for us anymore. Let’s not do that. Let’s change. Let’s evolve.”

There may not be a lot of agreement on what decolonizing philanthropy means, but getting funds into the hands of Indigenous organizations to be implemented and accounted for in ways that are meaningful and finding better ways of doing things that centre relationships are all things both TASSC and Toronto Foundation can agree on. Unprecedented times created unprecedented opportunities and new ways of working together to create change.