What do Indigenous Peoples mean when they talk about Indigenous philanthropy? Miles Morrisseau put this question and others to Indigenous people who are leaders in the philanthropic sector.

Well, as we all know, the white man speaks with a forked tongue because his words often have two meanings, or sometimes more. In the case of the word “reconciliation,” it has three distinct and widely accepted definitions:

1. the restoration of friendly relations

2. the action of making one view or belief compatible with another

3. the action of making financial accounts consistent

When we talk about reconciliation in Canada, the first definition is the most considered. Yet as such, it becomes a non-starter for many Indigenous people. This reality should not discount the value of the two other definitions. The act of reconciling one view or belief with another begins with agreeing on the true history of Canada and the historical and ongoing genocide against Indigenous Peoples. It also means reconciling the truth behind generational wealth and the legacies of those Canadians and their families who profited from the genocide of Indigenous Peoples.

A portion of that wealth fuels the philanthropic sector. However, it is a stunning yet little-known fact that only 1% of all charitable donations in Canada go to Indigenous Peoples. This disparity also fails to reconcile from an accounting definition.

To achieve reconciliation as a form of understanding, we must agree on what is true, what is real, what occurred in the past, and what is our shared future. We must also ask what philanthropy represents to Indigenous Peoples, and, as importantly, what we mean by Indigenous philanthropy. If these understandings can be achieved, then we can manifest the friendly relationships that create a better society and a sustainable world.

I put these questions to a number of Indigenous folks who are leaders in the philanthropic sector.

Kris Archie

Kris Archie is the CEO of The Circle on Philanthropy and Aboriginal Peoples in Canada (The Circle). She is a Secwepemc and Seme7 woman from Tsꞌqescen, a mother, aunty, and engaged community member. The Circle is an Indigenous-led and Indigenous-focused philanthropic advocacy and support organization.

I was the little kid who had a UNICEF box around my neck at Halloween, and then the little fundraiser for the Canadian National Institute for the Blind, selling raffle tickets at my school fundraiser. I had this idea that helping to get money from people to give to those less fortunate was just a no-brainer, a good thing to do.

Now, I worked inside of settler philanthropy. I worked for Vancouver Foundation for five years, as a manager in a program called Fostering Change, which was about grantmaking, research, youth, and public engagement to create policy change for youth exiting foster care to ensure supports to age 25. While at Vancouver Foundation, I was supported to participate in a US-based philanthropic fellowship program called PLACES, and it radicalized me. It gave me many realizations, one of which was noticing that for all the good that was happening – millions out the door – many more millions were just being invested for the purpose to amass more wealth.

Indigenous philanthropy is about highlighting and amplifying the variety of ways that Indigenous Peoples and communities give back.

Kris Archie

When we talk about Indigenous philanthropy, we often will talk about Indigenous-led philanthropic endeavours, such as the Arctic Funders Collaborative or the Ontario Indigenous Youth Partnership program. There are Indigenous-led community foundations. Granted, they behave very much like traditional philanthropic organizations, but they’re Indigenous-led and -operated. That in and of itself makes them better and different.

Indigenous philanthropy is about highlighting and amplifying the variety of ways that Indigenous Peoples and communities give back, in terms of the ways in which traditional knowledge, teachings, practices, and ceremonies uphold and demonstrate those kinds of practices for generosity, like Potlatch or blanket giveaways.

As I came to learn about community foundations, corporate foundations, and private or family foundations, what I noticed is that folks were so donor-centred. Even though they talked about “representing the community” or “supporting the community,” the people they were mostly talking about were the donors. Their notion of community was fucked right there. They’re thinking about the rich people. And even when rich people who are Indigenous or racialized walked in, they weren’t paying close enough attention to how to serve those individuals in the ways that they wanted.

Look, I’m here. I’m not here to fuck around. I’m here to work with you. And that means that I don’t play nice just because that’s what’s expected of Indigenous people and racialized or Black people in the sector. Right? The philanthropic sector is so nice. If you’re not nice and appeasing and giving people what they want – well, you’re rude and you’re young and you’re all the things that mean that you’re not to be taken seriously.

Mike DeGagné

Mike DeGagné is the president and CEO of Indspire. He is an Ojibway from the Animakee Wa Zhing 37 First Nation and served as Nipissing University’s president and vice-chancellor prior to joining Indspire.

My first job in the community was in 1978 at a small First Nation in Northern Ontario. They said, “We want to run a summer program for children in the community.” A lot of the kids really needed something to do during the summer. They were left to their own devices in a lot of cases. The First Nation said, “Look, we don’t have much money, but we want you to run a program. So you’re going to have to get on the phone and talk to local businesses and local individuals; not in the community, but outside the community. Ask them for donations. Let’s say you want to take the kids camping, somewhere to a spot on the reserve somewhere. You’re going to have to get supplies and such from the community outside reserve.”

I would spend afternoons working the phones, and that was a real eye-opener for me. First of all, there was so much pushback: “Why are you calling me to have me support Indigenous kids? They get all the support they need. They’re completely funded by government. Indigenous people need almost nothing. Everything’s provided for them.”

That was one of the things I learned really quickly about philanthropy for Indigenous people: you really do have to spend a lot of time telling the story of why people need the funds they need.

Mike DeGagné

Some of it was racist, but some of it was just misunderstanding. “I don’t know why you’d be calling me [when] the government gives so much. You should call the government.” That was one of the things I learned really quickly about philanthropy for Indigenous people: you really do have to spend a lot of time telling the story of why people need the funds they need.

DeGagné also recalls another revealing moment that occurred during an all-chiefs’ meeting in BC:

We were just about to start. I was sitting there with Georges Erasmus, former head of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, about to do a PowerPoint presentation, when the chair said, “Oh my gosh, we’ve just lost a great leader, a great chief.”

You know, when that happens, the business of the day gets set aside. We now focus on the loss of that person, as we do so often with funerals in our communities, and they pass the hat. The chair said his widow will be coming here shortly. The man had died the night before and she will be coming to the meeting to accept our condolences. So they passed the hat, and I will tell you, it was extremely generous, what they gave her to help her for her funeral arrangements and all the things her family needed.

There is that generosity and that taking care of each other and our own. That is not a story that’s well told. That’s kind of lost a bit. I wish it was told more often.

Liz Liske

Liz Liske is the director of the Arctic Funders Collaborative. She is a Yellowknives Dene First Nation member, a descendant of the Tetsotꞌine, copper people surrounding Great Slave Lake. She was born and raised in Somba Ké, Northwest Territories, on Chief Drygeese Territory.

We don’t have a word for philanthropy. But how I see it now is that we’re the original philanthropists. Giving and sharing is something that we’ve been doing since time immemorial. A good example of that would be with hunting and harvesting. When [hunters] are harvesting for big game like caribou or moose and they are successful in their hunt, they bring it back, the whole animal. They share not just with their family; they share it with the community, as much as they could, and that’s philanthropy.

Giving and sharing is something that we’ve been doing since time immemorial.

Liz Liske

It would be wasteful to keep the caribou to myself because I couldn’t eat the whole thing. We would just make sure everybody’s well and that you’re treating the animal in a respectful way. We understood all those levels of respect and being grateful and sharing, and we still practice that to this day. You see it in the treaties that were made: we will share this land with you. Indigenous people are still honouring those treaties today, despite the history that we have.

Sharing and giving – the way that it’s done [in settler philanthropy] is to benefit the giver or give them a tax break. It’s also a way they feed their ego: “Look at all the things that I’ve done.” That type of philanthropy represents a very specific difference between Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people. When Indigenous people do it, they don’t expect anything in return. They share as a way of honouring that person. I have these things to give myself life and I want to honour your life with these things and continue to give you life too.”

Andre Morriseau

Andre Morriseau, a member of the Fort William First Nation (Thunder Bay), is based in Toronto. A director on the Anishnawbe Health Foundation board, he has served on numerous boards over the past 20 years, including the Ontario Arts Council and the ImagineNATIVE Film and Media Arts Festival.

We need a renaissance of respect for Indigenous Peoples. There is an enlightened way for people who give to see Indigenous people. I think that everybody in this country should want everyone in this country to be playing on the same playing field, having the same access to healthcare, the same access to good education.

We see many extraordinary Indigenous organizations across the country that the average person doesn’t know about. In my experience over the past 20 years, I just see such a sea change. The Indigenous arts organizations in this country have strengthened and built a much more solid future. But they, too, have relied on charity.

A charity should be about coming together, an opportunity to learn, an opportunity to share.

Andre Morriseau

Charity shouldn’t be seen as something that’s just about giving money and that’s the end of the conversation. A charity should be about coming together, an opportunity to learn, an opportunity to share. When people are giving money to Indigenous organizations, I think that they really do need to do their homework and learn more about what they’re giving to, and to turn it into a learning experience.

The other thing about charity is that people need to listen. There needs to be more listening to what Indigenous needs are, and understanding them for what they are. The listening part is so important.

At the Anishinawbe Health Foundation, we’re very excited. This past June, we had the ground-breaking for the new health centre. This is an extraordinary part of that new optimism and confidence that is changing things on the ground. It is through extraordinary giving that we’re able to support this extraordinary endeavour.

Jana Angulalik

Jana Angulalik is a freelance contributor to the CBC. She grew up in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, and has lived in Indonesia and Australia. An Arctic Indigenous Fund advisor, esthetician, and a traditional Inuit tattoo artist are a few roles she’s honoured to hold.

I picture strong support for our Indigenous communities when I think of Indigenous philanthropy because I just know there’s so much imbalance in the world. Indigenous philanthropy to me means supporting those of us who have been under-supported and marginalized.

It still brings me to tears knowing how far as a people we have come, and how much knowledge is still being created and passed on. We’re one of the world’s fastest-colonized people. And so, we’re still in that morphing realm, I find. So when I come across blocks and textiles for children and toddlers to play with and learn from – not only syllabics, but there were blocks with animals that we could identify that the children could identify, and that meant something to them, because those were animals that they can hunt and see out on the land. And so that was a really touching moment just to see our funding be a part of something that is intergenerational.

I picture strong support for our Indigenous communities when I think of Indigenous philanthropy because I just know there’s so much imbalance in the world.

Jana Angulalik

I don’t know if anyone else experiences this: as an Indigenous woman, when you go walk in southern Canada – the further I go from Edmonton, the further I go from the North – the more eyes gaze upon me. They’re just like, wow, this person has a forehead tattoo. I’m very visible. I’m of another ethnicity other than white.

We had gathered from all parts of the circumpolar North in a board room, just to do an overview of what was going to happen that coming week. We quickly wrapped that up and we hopped on skidoos and went to a camp to have our introductions with each other, to have that conversation on why we are there as advisors for Arctic Indigenous Fund and what motivates us to do the work that we do. Those kind of deep, meaningful conversations we try to have very intentionally. That was outside around a fire that we had built together, maybe with spruce boughs. It was a natural place out in nature, and it was “Wow, that felt like luxury.” What it felt like was coming home, or going home in a sense, even though I’m not from that area.

Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair

Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair is Anishinaabe (St. Peter’s/Little Peguis) and an assistant professor at the University of Manitoba. A regular commentator on Indigenous issues on CTV, CBC, and APTN, and co-editor of two academic anthologies, he is a member of The Philanthropist Journal’s editorial advisory board.

Philanthropy is a thing of privilege. While it’s valuable and important, you can only give away your time and your money when you’ve assembled enough that you are beyond your own means. So it’s a concept that wouldn’t work as much for Indigenous people because our whole life is about interaction and relationship with other things. The notion of “profit” would be something we would never get to. If you had too much moose, you would have already shared that with your family. You would have been like, “Okay, so who do we got to share it with?”

You’re shamed if you came home and kept all the moose. It’s not that you couldn’t do it, but you certainly wouldn’t. It would evoke a sense of individuality within the society.

The notion of ‘profit’ would be something we would never get to. If you had too much moose, you would have already shared that with your family. You would have been like, “Okay, so who do we got to share it with?”

Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair

I’ve been on a lot of these committees for philanthropy organizations. They’re often characterized as “Isn’t this great that we’re giving this money to this community to help them build broadband internet?” And I’m like, “Well, why didn’t they have broadband internet in the first place?” Like, that’s supposed to be a treaty right. That’s the question in philanthropy that’s tough. The metaphor I used was “We should never be asked to feed the Elders first at a feast.”

The concept of philanthropy is flawed for Indigenous Peoples, but then there’s also a reality, which is that the government won’t be able to pay for these things or won’t want to pay for these things. So what we need is that those who have profited mightily off the lives of Indigenous Peoples should help participate in the recovery and the restitution and the revitalization of our communities. So what we need is that those who have profited mightily off the lives of Indigenous Peoples should help participate in the recovery and the restitution and the revitalization of our communities.

Carol Hopkins

Carol Hopkins, executive director of the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, is of the Lenape Nation at Moraviantown, Ontario. Thunderbird is a non-profit committed to working with First Nations to further the capacity of communities to address substance use and addiction with a holistic approach that values culture, respect, community, and compassion. Its top priority is developing a continuum of care available to all Indigenous people in Canada.

What the Elders talk about is how we adjust and adapt. I think about philanthropy in that way. We have original core values that support the idea of sharing and giving resources, but it isn’t always just about money. It’s about a way of life and a way of living. As the world around us changes, it doesn’t mean that our values and worldview and ways of living our culture remain static. We have to let things go. We are in a time of change, and we have to adapt to that change.

We have original core values that support the idea of sharing and giving resources, but it isn’t always just about money. It’s about a way of life and a way of living.

Carol Hopkins

That’s critical because if we don’t figure out what the change is – whether it’s climate change, social injustice, social emergencies, our kids being taken away, or the high rates of suicide or the high rates of addictions and violence in our communities – if we can’t figure out how to adapt and apply our values and cultures and ways of doing things in a new way, then we won’t have that to pass on to the future and we’ll leave them with nothing.

In First Nations communities that are struggling with opioids, methamphetamine, and all of the issues that go along with that, they’ve begun to work with Elders and cultural practitioners to implement land-based programming. They don’t have resources for infrastructure to build buildings and detox centres or clinics. But they’re going out on the land. They have cabins on the land or they have Elders who can teach people how to build shelters out on the land.

Going out on the land is facilitating that spiritual connection with them, our first family, which is creation, our mother the earth. It’s teaching people about where medicines come from. It’s teaching people about the importance of their identity. Helping people to find meaning and purpose in their life.

Our responsibility is to ensure the future – that we don’t pass on our problems to the future, that we are working to figure out solutions, that we are educating for adaptation. And understanding change and adaptation doesn’t mean that we change the original meaning of the values held within our worldview. It means we’re learning how to apply it in a different context.

Indigenous philanthropy is about ensuring that the resources that we share are grounded in Indigenous knowledge and culture.

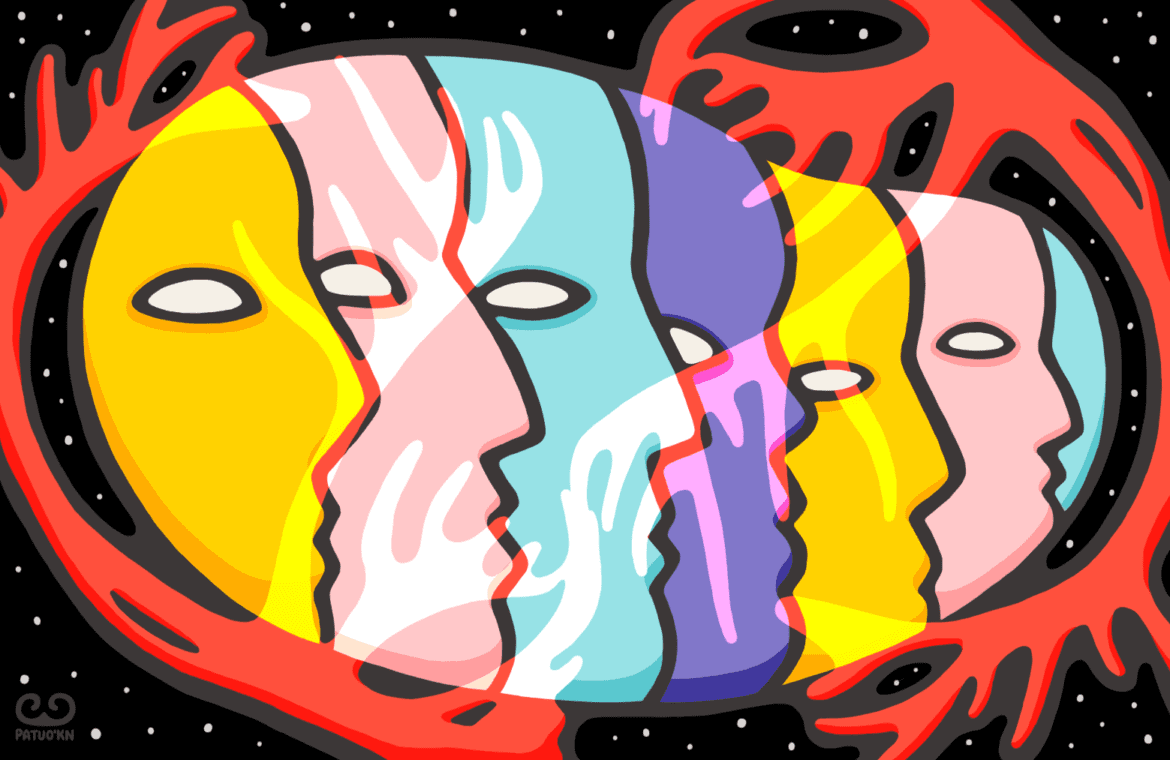

The illustration that accompanies this piece is by Patuoꞌkn Illustration and Design.

“While sitting with the discussions that Miles has gathered, I really connected with the concepts of interconnectedness and oneness that we have with the natural world around us, in regard to how we view philanthropy as Indigenous Peoples. The ways we respectfully share wellness in the current moment, as well as intergenerationally, were key messages to me. Having lived experience being Lꞌnu in Miꞌkmaꞌki, these messages of reciprocity, sharing, and community holistic wellness really rang true.

The main elements in this illustration are the people and the qalipu (the Miꞌkmaw word for caribou). I’ve placed the people within the dynamic oval shape to represent how we’re all a part of the cycle of respecting, receiving, giving, and sharing. The antlers that frame the faces represent not only the way we share our harvests with community, but also the different components within philanthropy and the way that it weaves through people. The cascading line of faces represents our relations, community, and our next generations – all moving in the same direction together. The deep colours represent the emotional depth and strength of Indigenous philanthropy and the inner fire that we as Indigenous Peoples hold within us to protect each other and our traditional ways of life.” —Kaylyn Bernard, Patuoꞌkn

***

Patuoꞌkn Illustration and Design is run by siblings Kassidy and Kaylyn Bernard, from Weꞌkoqmaꞌq First Nation, Miꞌkmaꞌki. Their business is based out of Unamaꞌki (Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia). “Patuoꞌkn” is a Lꞌnu (Miꞌkmaw) word for “driftwood.” The idea for the name came from their grandfather Saln (Charlie) Bernard, who ran his own roadside business selling handmade driftwood crafts just off of Highway 105 in Weꞌkoqmaꞌq, where he lived. To honour their language, family, and creative history, they decided to carry on their grandfather’s business name. Their grandfather’s knack for teaching passersby about Lꞌnu ways of life through his work was embedded in their father, Robert Bernard, who has passed these teachings down to them. Now, after being in business for three years, Kassidy and Kaylyn have worked with over 60 clients and continue to develop their own ways of sharing cultural awareness through visuals, with cultural revitalization and preservation at the forefront. They focus on serving Miꞌkmaw and other Indigenous clients, especially those who provide educational materials for learning Indigenous languages, culture, and practices. They also strive to work with local artisans and small businesses to strengthen and uplift the visual presence of Lꞌnu culture in Miꞌkmaꞌki. If you’d like to learn more about Patuoꞌkn, you can visit their website at patuokn.com.