From neighbourhood efforts to improve employment to national efforts to tackle climate change, non-profit organizations in Canada are increasingly turning to the science of networks to inform the way they structure themselves, who they engage with, the actions they take, and the way they determine and measure success.

This is the second article in our series about the role of networks in the non-profit sector. The series is published as a collaboration between The Philanthropist and the Ontario Nonprofit Network.

From neighbourhood efforts to improve employment to national efforts to tackle climate change, non-profit organizations in Canada are increasingly turning to the science of networks to inform the way they structure themselves, who they engage with, the actions they take, and the way they determine and measure success.

Anne Gloger of Connected Communities in Scarborough, Ontario, was an early adopter of the network approach. When people in the Kingston-Galloway/Orton Park community – where the organization she helped found is located – wanted to improve employment opportunities for low-income residents, she brought together employers, labour, employment agencies, residents looking for employment, and funders to map out job opportunities and connect people to them.

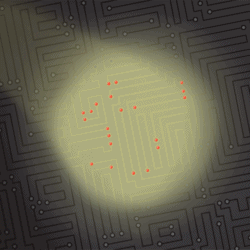

The first map showed two distinct but loosely connected hubs, with many individual connections to the people in their centres. It revealed a heavy reliance on these two players, and a lack of relationships and connections between the many other people on the map. The group immediately saw how vulnerable they would be if those two key players could not continue the work – so they began to foster collaboration with others linked to many small projects, opening opportunities for employment with local employers. The network approach served as a compass to help find new partners and resources within the neighbourhood and it informed the choices the group made to build community resilience.

The fundamental essence of a network approach revolves around adopting this informal style of working, one that emphasizes relationships and connections that can form and reform as new challenges or opportunities emerge. A network can draw on the necessary people and expertise and later release these resources once the work is complete. It is collaborative by nature. This article will explore the nature of networks and how they form and evolve over time, describing how to lead within them. It will also include examples of the kinds of principles and values that guide a network approach.

Network formation and evolution

Networks can be formal or informal, explicit and visible or implicit and hard to see, generative and inclusive or exclusionary with closed boundaries and limited access. Networks represent people working together and, even though those involved often have different values and goals, they realize they can all benefit by sharing experiences and strategies.

As the internet has flourished, we can see and track our connections better than ever. The science of networks has emerged, helping academics and practitioners understand how they form, how to make them more productive and effective, and how to be strategic in applying a network approach.

Public benefit non-profits have embraced a network approach at the local, regional, provincial, and national levels. Before non-profits used online platforms for engagement, networks tended to operate in leader-to-leader structures that felt more like formal organizations. For example, executive directors often met by phone or in person. But today, the potential to connect frontline staff and volunteers who have the knowledge and skills to quickly address problems is driving new collaboration efforts. The Ontario Coalition of Agencies Serving Immigrants (OCASI) and two other partners, Meta Strategies and Vancouver-based MOSAIC, are working together to form a national network for the newcomer-serving sector in Canada. Recognizing that most organizations in this sector cluster geographically – some in local networks and some more loosely aligned – they created a national planning group, surveyed members and realized the benefits of connecting these organizations. These include shared learning opportunities and the ability to tap into the knowledge of local members. The network structure provides flexibility, responsiveness, transparency, openness, and inclusiveness.

A network approach also helps identify common cause, while distributing power and resources to involve many people in building solutions. It allows people to find one another through trusted connections so they can work together in reciprocal ways. Because networks involve different interests working together, they usually pay attention to the potential for impact and variation at multiple points and scales within the system. Thus, networks have become useful in developing public policy approaches.

Networks often reflect the non-linear dynamical attributes of the self-organizing systems within which they operate. They create results because of the many ways people work together: there are no simple cause-and-effect outcomes. Instead, it is often the multiple efforts of many that simultaneously lead to collective change because a wide distribution of power and resources resists control from the centre.

In his new book, Collaborating with the Enemy: How to Work with People You Don’t Agree with or Like or Trust, Adam Kahane describes an approach called “stretch collaboration,” – the challenge of bringing a diverse network of people together to find a point of common agreement. Typically, some people begin by thinking they have the solution, if only others would listen. Kahane describes the process he and his colleagues at Reos Partners use to surface common points and take small actions to see what solutions will work.[1]

June Holley, a US-based maven of network theory and master network weaver, also believes the best way to build high quality relationships within networks is through multiple small actions by people working in groups of two or three. She believes trust emerges through these mutual actions.[2]

Core and periphery

Research conducted by Holley and her colleague Valdis Krebs identified the stages of network growth, beginning with scattered fragments that form into a single hub-and-spoke structure.[3] As the network grows, multi-hub and spoke structures emerge, similar to the pattern of relationships Gloger and her network identified when mapping Kingston-Galloway/Orton Park. Through working on many small projects, networks become denser, with nodes and links shifting into a core-periphery structure with many overlapping clusters. Krebs and Holley call this a “network of networks” of people from different sectors or geographic regions or professions. Those in the core represent the network weavers or coordinators: those most active in the network. They have a good sense of who belongs to the network and where its knowledge and action live. Not everyone in the core will know each other, but they are only one or two degrees away and can easily make those connections when needed.

The edges of a healthy core-periphery network are typically three to five times the size of the core. The periphery is important because it is the source of people who hold critical information and diverse perspectives or experiences. They often represent the weaker links that help networks grow and access new insights or resources. Krebs and Holley note the importance of continuously growing and expanding the periphery as a critical skill of network weavers. Ideally, people in the network should be able to access the resources they need by taking the fewest steps.

A future challenge for the group in Kingston-Galloway/Orton Park will involve learning to scale their efforts to support other communities seeking better employment opportunities. Efforts to weave new communities and resources into their network will help them span their community’s existing boundaries and build bridges across geography, employment practices, and job skills.

Holley says in her book: “Systems change when new networks supplant the old.” At the core of this is the implicit role networks play within systems. Understanding the patterns of an existing network and identifying key leverage points helps weavers know where to intervene. This can build stronger, more open, and diverse networks, allowing change to happen.

Whether you map a network formally using surveys and network mapping software, or informally, it will reveal gaps, identify blockages in the flow of information or resources, and demonstrate the open or closed nature of a network’s boundaries. These exercises can help participants see how to span existing boundaries, open membership, or infuse resources and opportunities where they are most needed.

Sometimes people need to form new networks to supplant oppressive or racist powerbrokers or systemic practices. Networks are key to understanding system change. The Black Lives Matter and Idle No More movements are two examples of this kind of shift.

The Sustainability Network has been working to grow and support a network of environmental organizations across Canada for 20 years. Its mission to strengthen environmental non-profit leadership includes building organizational capacity and developing the skills of the people within the network. Network staff and members watch for emerging issues and opportunities and then convene groups or develop programs and services collaboratively. They also work closely with funding bodies to monitor shifts in priorities and support members to access new funding opportunities. “We work with both large established organizations and new and emerging groups, recognizing the emerging groups reflect a response to something new in the environment,” said Paul Bubelis, executive director. The network uses a range of opportunities – from online gatherings to a spring annual general meeting and a fall retreat – to check in with its members. It also plans regular in-person learning events. For Bubelis, opportunities to gather in person trump digital collaboration. In his experience, real challenges emerge when networks have a chance to spend a day or two together and enjoy some down time. He has learned that people need to build trust if they are going to truly collaborate.

Network leadership

Gloger and Bubelis emphasize that network leadership is different from organizational leadership. A 2015 article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review describes a way to think about network leadership. The article, provocatively titled “The Most Impactful Leaders You’ve Never Heard Of,” describes network leaders as “network entrepreneurs,” leaders who work to ensure the power of others grows while their own power fades, thereby developing their network’s capacity. This results in a culture of distributed leadership that dramatically increases the efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability of the collective effort. The article outlined the following qualities of network leaders:

- Trust: Network entrepreneurs emphasize that collaborations are not likely to succeed unless people build them on foundations of mutual respect and integrity, often generated through mutual projects. Entrepreneurs must create these efforts to build trust.

- Humility: Unlike social entrepreneurs who emerge as hero-like figures, network entrepreneurs are often largely anonymous by design. Early on, leaders are visionaries and help develop a sustainable structure to engage diverse participants, but they are deliberate about ceding power to the collective leadership and developing the capacity of the whole network.

- Node not hub: Network entrepreneurs resist keeping themselves in the centre while actively connecting to the larger system around them. They are often concurrently supporting the growth of local action-oriented networks. Through their actions and beliefs, network leaders model a culture where no one person or organization seeks to be the brightest star.

- Mission not organization: Network entrepreneurs are motivated to achieve maximum social impact even if it does not advance their personal, or their organization’s, goals. Network entrepreneurs will refer funders to members in the network who are better able to deliver rather than try to find a way to spend the money themselves.[1]

Leaders also follow

It is not surprising that the traits of network entrepreneurs complement the traits of “network weavers,” the term credited to Holley. She sees the roles these people play as a mix of convener, facilitator, connector, guardian, and collaboration catalyst. Rarely does an individual have all these abilities, but people in a network will have strengths in one area or another. Holley would argue that everyone is potentially both a leader and follower in a network.

The work of network leaders is to imbue the network with a culture that encourages everyone to engage, act and participate in ways that collectively amplify the impact of the intended work and grow and sustain the network as result of doing the work.

When I was first introduced to the Network Weaver Checklist (a tool Holley developed to help people understand what skills they possess), I started rating myself according to each attribute and thinking, “I have this,” consistently scoring myself high – until I was stopped cold by the statement: “I love to unearth other people’s dreams and visions.” I realized I rarely took the time to find out the longer-term aspirations of staff and colleagues. I started to ask the question and I discovered remarkable things. I was soon able to quickly connect people with the opportunities and people who could help them achieve their dreams and goals. A surprising thing started to happen: as I shared with others, they shared back. The rich reciprocity generated a flow of opportunities and experiences for my own career and a learning path I never expected.

To make networks more productive and generative, Holley and Krebs like to say “know the net and knit the net.” Mapping a network lets you “know the net.” You can use pens and paper or software like Kumu or InFlow. These maps are often java-enabled and can build visual images of networks at a given point in time. Comparing the size and structure of network maps over time can help a group track progress and identify emergent leadership. Depending on the program, it may also provide quantitative data on measures such as centrality, network integration, and reach. Maps are always just a snap shot; they need to be repeated to show shifts and changes over time.

To “knit the net” Holley suggests “closing triangles” within the network. That involves network members intentionally looking for opportunities to introduce people based on a hunch that they will have a reason to take action together or learn from one another. By closing the gap between two people who had previously not known each other, you create a new link; a new relationship within the network. This builds network strength and resilience. Mapping helps leaders know where and how to close triangles. Other strategies already mentioned might include creating both formal or informal learning events, creating temporary working groups, and developing opportunities for network members to come together to reflect on accomplishments, assess progress, and explore new possibilities.

As more people work in networks and experience the power they can generate, more useful resources have become available. The Interaction Institute for Social Change is an excellent source of inspiration for developing skills as a network leader. Its network-building focus has an explicit purpose to “design and facilitate collaborative . . . connectivity networks . . . to tackle society’s most intractable problems.”

Network principles

The global Social Innovation Exchange network recently published an article about its use of networks, noting both the growth and proliferation of networks and the challenge of building and facilitating them. With 16,000-plus members, it relies on a number of principles and features to encourage a network approach, including being people-focused; employing productive disruption; connecting as peers based on interest area, not job title; and empowering members though democratized innovation.

Meanwhile, the Ontario Nonprofit Network recommends the following set of principles or minimum specifications to guide how it takes action as a network:

- Work is action and energy focused. “What do we need to accomplish and what is the best way to get there?” Pre-determined structures might help, but they don’t necessarily drive the way we work.

- Balancing order and chaos. Plans can change a lot, so flexibility is key.

- The network is smarter than any one of us. Working groups with diverse people from the network provide multiple viewpoints on an issue.

- Learning from failure. When an approach isn’t working, or something we’re trying comes to an unexpected end, we need the confidence and humility to let go, disband, and move on.

- Speak truth to power. Even when it’s not popular, stand by core values.

- A clear common motivator. There’s a reason for the work of the group. Answering “Why are we doing this together?” should be easy.

- Agreeing to disagree. Getting organized as an ONN group is not binding on partners’ other work. We need common interest, not full consensus.

- Self-interest is acknowledged and harnessed for mutual benefit. Not everyone needs to have the same reason to be at the table, but surfacing why we’re there helps us move toward common goals.

- Leadership is shared, not hierarchical. The goal is not for one group to command others, but to join-up everyone’s contributions.

- We win together. We want to build up the leadership of others and redistribute opportunities and resources to those who may be better positioned to take them on. We’re stronger working together![5]

Connected Communities follows a similar set of principles, including people and process over product, the importance of context, a focus on strengths and tuning into the possibilities as they emerge. Many of these reflect the attributes of complex systems which are non-linear and sensitive to local context. Linear systems rely on outcomes that equal the inputs while non-linear systems can’t predict the change based on the input. Small changes can lead to big impacts. Despite our best efforts to predict the future with big data and modelling, complex systems by their nature are unpredictable. Uncertainty will always be a part of the equation. Networks help us embrace that uncertainty as people loosely collaborate and connect with one another, constantly scanning the environment and tuning into the edges for signs of change or shifts that may require adaptation.

In reflecting on the principles above, one can see several common themes:

- Build relationships and trust;

- Find common cause among diverse members to motivate change and inspire progress even if you do not initially agree on solutions;

- Take risks and speak up even when it feels hard to do so; and

- Embrace distributed leadership and always defer to the people in the network with the greatest skill, not position.

This approach creates the conditions for perpetual novelty and innovation, and that is what we need when the challenges we face are big and solutions require the collective intelligence and experience of many people. Adopting a network approach provides new ways of seeing into what can sometimes feel like very messy and uncertain sets of relationships and territories. By letting go of formal hierarchies and structures, we create space to let new ideas emerge that can be embraced by those who are working most closely with our biggest social challenges.

[1] From “The Most Impactful Leaders You’ve Never Heard Of” by Jane Wei-Skillern, David Erlichman and David Sawyer, SSIR.Org September 16, 2015 https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_most_impactful_leaders_youve_never_heard_of

[1] Adam Kahane, Collaborating with the Enemy: How to Work with People You Don’t Agree with or Like or Trust, Berrett-Koelher Publishers, Oakland California, 2017

[2] See Holley’s Network Weaver Handbook https://www.networkweaver.com/product/network-weaving-handbook/

[3] See Valdis Krebs and June Holley, Building Smart Communities Through Network Weaving, https://www.networkweaver.com/

[4] From “The Most Impactful Leaders You’ve Never Heard Of” by Jane Wei-Skillern, David Erlichman and David Sawyer, SSIR.Org September 16, 2015 https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_most_impactful_leaders_youve_never_heard_of

[5] Networks + Action http://theonn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ONN-Networks-Action_2015-06-05.pdf