Introduction

Talking About Charities 2004: Canadians’ Views on Charities and Issues Affecting Charities was released in October 2004.1

The study, carried out by Ipsos-Reid for The Muttart Foundation, was the second wave of public opinion polling commissioned by the foundation to provide information of use to charities and public-policy makers.2

Almost 3,900 Canadians completed a 20-minute telephone interview that measured their views on everything from their trust in charities to whether business activities of charities should be taxable. A sample of this size is considered accurate to within 1.6%, 19 times out of 20.3

The study confirmed results from the first survey conducted in 2000.4 Canadians continue to report high levels of trust in charities and charity leaders. The level of acceptance of advocacy activities by charities grew between the two studies. And most Canadians continue to believe that charities do not have enough money to fulfil their missions.

At the same time, some of the results may not be as warmly welcomed by the charitable sector. Canadians rate charities poorly at providing key information that respondents say they want. They believe that when charities are advocating, they should be required to provide both sides of the issue. Canadians say that more attention should be paid to certain key operations of charities. They have concerns about some fundraising practices.

The study reveals misconceptions among the public that could, if not addressed, lead to an erosion of trust in charities and to actions by policymakers that would not likely be welcomed by the sector.

Trust

Trust in charities and charity leaders remains at very high levels. Almost 80% of Canadians reported that they trust charities, with almost 30% saying they have “a lot” of trust. This represents a slight increase in trust when compared to findings from the 2000 survey.

Similarly, Canadians repose significant trust in the leaders of charities; only nurses and doctors earned higher levels of trust.

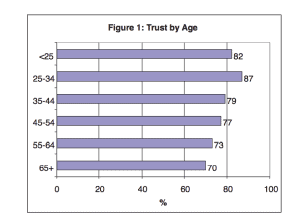

These are numbers to be applauded. But underneath them, there are significant differences in the degree to which Canadians trust charities. As Figure 1 shows, the level of trust peaks among people between 25 and 34 years of age, where 87% of respondents said that they trust charities “a lot” or “some.” From that point, levels of trust decline.

Figure 1: Trust by Age

Throughout the study, responses by people 65 years of age and older were consistently more negative toward the charitable sector than were those of other respondents. While it can well be argued that an approval rating of 70% among this group is still more than satisfactory, the reduced level of trust could also be a harbinger. It may suggest that as society ages, if seniors continue to view the sector more negatively than do other Canadians, more attention will need to be paid to increasing the level of trust. This may be particularly true for organizations that are hoping to benefit from the intergenerational transfer of wealth that has been much described.

While trust levels decrease with age, they increase with education and income. Among those respondents with less than high-school education, only 64% reported they have “a lot” or “some” trust in charities. That figure rises to the mid-80% range among respondents with at least some university education.

Similarly, the lowest levels of trust (77%) are among those reporting total household incomes of less than $50,000. Trust levels increase as income increases, peaking at 88% among those with household incomes of more than $100,000.

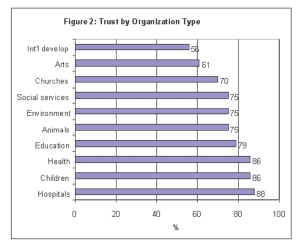

When it comes to trust, however, all charities are not created equal. As shown in Figure 2, when respondents were asked to indicate their level of trust in various types of charities, there were definite winners and losers. Just over half of respondents reported “a lot” or “some” trust in international development organizations, whereas the vast majority (88%) reported “a lot” or “some” trust in hospitals.

There are a few demographic differences in responses that assessed the trust level in the various types of charities. Again, age plays a factor, with the trust in charities that focus on children and children’s activities decreasing as the respondent’s age increases. Among those 65 years of age and older, the level of trust in that type of charity decreases to 74%. For both international development charities and arts groups, women were more likely to express trust than were men.

Trustworthy Leaders

The same high ratings of trust were reported when respondents were asked to indicate how much trust they have in people from various professions or callings. Again, 80% of respondents said they trust leaders of charities “a lot” or “some.” What is interesting, however, is that the strength of that feeling is weak—only 24% said they trust charity leaders “a lot.”

By comparison, there is strong trust in nurses—96% overall, with 73% saying “a lot”—and medical doctors—93% overall, with 61% saying they trust medical doctors “a lot.” Still, charity leaders enjoy a higher level of trust than do most other professions and callings. Figure 3 shows the percentage of respondents who said they trusted various professions or callings “a lot” or “some.” Business leaders had a 68% trust-level rating, followed by religious leaders (67%), government employees (66%), journalists/reporters (63%), lawyers (59%), union leaders (51%), provincial politicians (33%), and federal politicians (30%).

The ratings of charity leaders show the same demographic patterns as those revealed by questions asking about trust in charities. Older Canadians are less likely to trust leaders of charities, while trust increases with a respondent’s education and total household income.

FIGURE 3: Trust by Profession

|

Trust a lot (%) |

Trust some (%) |

Total (%) |

|

|

Nurses |

73 |

23 |

96 |

|

Medical doctors |

61 |

32 |

93 |

|

Charity leaders |

24 |

56 |

80 |

|

Business leaders |

11 |

57 |

68 |

|

Religious leaders |

22 |

45 |

67 |

|

Government employees |

13 |

53 |

66 |

|

Journalists/reporters |

13 |

51 |

64 |

|

Lawyers |

13 |

46 |

59 |

|

Union leaders |

10 |

41 |

51 |

|

Provincial politicians |

2 |

30 |

32 |

|

Federal politicians |

2 |

28 |

30 |

Funding

Canadians seem, as a whole, to accept that charities do not have enough money to meet their objectives. While this mirrors the results of the earlier study, there was a significant increase in the number of Canadians who felt this way.

In the 2004 study, 70% of Canadians said that charities have too little money to meet their objectives, compared with 59% who gave that answer four years earlier. Provincially, the most significant increases were in Ontario (68%, up from 54% in 2000) and Alberta (67%, up from 60%). However, it is in Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia where the feeling is most prevalent—80% of respondents in those two provinces felt that charities had too little money to meet their objectives.

That finding makes it even more difficult to understand another result of the study: almost 60% of Canadians believe that charities should be expected to deliver programs and services that the government stops funding.

This idea that charities should—or even can—pick up government’s castoffs is even more frightening when one finds that it is supported by a majority in almost all demographic groups. Among people up to 34 years of age, two thirds of respondents expect charities to deliver programs and services that are defunded. Although the feeling diminishes as the age of respondents increases, a majority of respondents in all age groups share this belief.

Of those who believe that charities do not have enough money to fulfil their objectives, 57%—matching the national average—believe that charities should be expected to deliver defunded programs. The figure is even more staggering in Quebec. In that province, 71% of respondents said charities do not have enough money to meet their objectives, but 69% said that they expect charities to fill gaps caused by government cutbacks.

The majority view is also held across all educational categories and among all income levels, except for those reporting total household incomes of more than $100,000, where only 48% agreed that charities should be expected to deliver defunded programs and services. Among the provinces, only British Columbia showed fewer than half of the respondents agreeing with this sentiment; there, 45% agreed.

This view—potentially a challenge for the sector if it fails to either meet or change this public expectation—comes despite the fact that most Canadians accept that it is difficult for charities to raise the funds they require: almost all respondents – 95%—agree that it takes significant money for charities to raise funds.

Canadians have strong views about fundraising practices as well. Although 78% believe that charities are generally honest about the way they use donations, this represents a 6% decrease since the earlier poll in 2000. However, there was also a decrease—from 74% to 69%—among Canadians who believe that too many charities are trying to get money for the same cause.

And there is still a bit of a credibility challenge. Only half of respondents (48%) believe that charities ask for money only when they really need it. This belief decreases as household income increases. Among the top-income level—those reporting household incomes of more than $100,000 — only one third of Canadians reported that they believe charities ask for money only when they really need it.

Commission-based fundraising continues to be frowned upon by most Canadians. More than six in ten think that percentage-based fundraising is unacceptable. Those who are prepared to accept it believe that the appropriate amount to be kept by a fundraiser is 14%—well below the amount that is often really kept.

The acceptability of commission-based fundraising diminishes with the age of respondents. Almost half of respondents under 25 years of age would accept the practice, while only one quarter of those aged 65 and older think it should be allowed.

Canadians are divided, however, about use of charitable donations for administrative costs. About 43% of Canadians believe that the full amount of a charitable donation should go toward the cause for which it was raised, with the remainder accepting that some reasonable amount should be allowed to be used to cover administrative costs.

As with the study four years early, almost all Canadians (94%) believe that charities should have to disclose the intended use of donations on each fundraising request. More than two thirds of Canadians said they hold that view strongly.

Failing Grades

Perhaps of most concern to Canadian charities should be the poor ratings they received on providing information that Canadians say they want.

Respondents were asked how important it is that they have information on:

• how a charity uses donations;

• the charity’s programs and services;

• the charity’s fundraising costs; and

• the impact of the charity’s work.

They were then asked to rate how charities perform at providing information on these four topics.

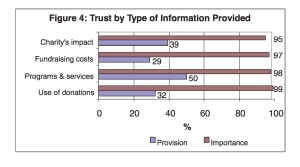

Figure 4: Trust by Type of Information Provided

Figure 4 shows the results of these questions—with charities getting a barely passing grade on providing information about their programs and services and clearly unacceptable ratings on the other three topics. For example, although 99% of respondents think it is important for charities to provide information on the use of donations, only 32% reported that charities are doing a good job at actually providing this information.

The responses also show that Canadians are not aware that the activities of charities are currently monitored, although it’s equally clear that respondents want them to be.

Almost seven in ten Canadians believe that charities’ activities aren’t being monitored (58%) or don’t know (11%) whether or not they are monitored. Even higher numbers believe that various aspects of the operations of charities should be monitored more closely.

Respondents were asked whether they believed more attention should be paid to any of four aspects of a charity’s operation:

• the way a charity spends money;

• the way a charity raises money;

• the amount of money a charity spends on program activities; and

• the amount of money a charity spends on professionals to do fundraising. In each case, at least 86% of Canadians called for greater monitoring. For spending generally, that figure rises to 95%. These figures hold true across

almost all demographic categories.

Given a choice of having charities monitored by a government agency, the charity’s board of directors, or an independent body, almost two thirds of Canadians opted for an independent agency.

Advocacy

Talking About Charities 2004, like the original study, asked Canadians for their views about the involvement of charities in advocacy activities.

Almost eight in ten Canadians (78%) said that laws should be changed so that charities can advocate more freely for their cause. However, an even higher number—83%—said that charities should be required to present both sides of an issue when undertaking such advocacy.

A majority of respondents found almost all forms of advocacy acceptable, ranging from speaking out on issues through meetings with government officials to letter-writing campaigns and advertising. Even holding protests or demonstrations was considered acceptable by a majority of respondents. Only “blocking roadways or other non-violent acts” was rejected by the majority, but even then, one third of Canadians would find it acceptable.

Implications

The results of this public-opinion study would seem to suggest that Canadian charities, as a group, have not done a superb job of informing Canadians about the role of the sector.

Clearly, Canadians believe that the sector is not doing a good job of providing information about their operations. The reality is that information is publicly available, most often from the charity itself but certainly from the data collected by the Canada Revenue Agency.5 However, it is clear that the public does not know that the Agency is responsible for monitoring the activities of charities, so it is not surprising that individuals would not know to look there.6

The fact that a significant majority of Canadians believe that charities should

– or even can—deliver programs and services that government stops funding is another indication that the sector does not do a good job of telling its story. It is clearly evident, from the National Survey of Nonprofit Voluntary Organizations and other research, that reductions in government funding cannot be easily replaced by private donations. Yet the public clearly has not received that message.

One could argue that there is no need for the sector to provide this information. In the first case, on the question of accountability to a regulator, one could say that it is the regulator’s role to advertise its existence. Similarly, one could say that given the high level of trust, there is no need for charities to be worried about whether the public is knowledgeable about the sector.

Such an argument, however, has two flaws. First, as organizations devoted to providing a public benefit, charities —regardless of their type or size—are accountable to the public. Even those charities that receive few donations from the public derive a benefit from the tax exemption they enjoy, at least on their income. To argue that this accountability can be transferred to the regulator (even if known) is to fail to recognize that trust can be a fragile commodity. While overall trust levels remain high even in the face of concerns about the transparency and spending habits of charities, one cannot assume that this will always be the case.

Second—and potentially more important—the argument that charities need do nothing would reflect the faulty assumption that public-policy decisions are based only on informed public opinion. The public does not need to be right when it calls for increased transparency and increased accountability; it simply needs to make that call loudly enough. And, it is argued, the percentages of Canadians with views on these issues constitutes volume.

Recently, some government officials have expressed increased concern about what they term deceptive and predatory fundraising. Although they are rarely able to point to anything other than isolated instances, the results of this public opinion poll provide some fuel to their argument that Canadians want even greater disclosure of information by charities. Thus, despite the fact that there are high levels of trust, the survey results suggest there would likely be no significant public distress if government (at whatever level) were to increase regulatory oversight and disclosure requirements.

The charitable sector rarely acts as a sector in explaining to the public the way charities work or the constraints they work under. There have been a few efforts over the years, but none that seem to have enjoyed any longevity. If that is not corrected, the sector may well be setting itself up for a regulatory system it dislikes and that, on the whole, may not be needed.

NOTES

1. The results of the study, together with charts and demographic breakdowns, are available on The Muttart Foundation Web site at <http://www.muttart.org/surveys.htm>. Printed copies of the study are available for nominal cost from Volunteer Calgary and the Resource Centre for Voluntary Organizations at Grant MacEwan College, Edmonton.

2. The Foundation has announced that it will repeat the study in 2006 and 2008.

3. Provincial results and results of particular demographic groups have higher margins of error. See the complete text of the study for details.

4. The first version of Talking About Charities was carried out by the Canadian Centre for

Philanthropy and the Institute for Social Research at York University.

5. The public portion of the annual information return (or T3010) of every registered charity is posted on the Canada Revenue Agency Web site. For those without Internet access, the return of any charity can be requested from the Agency by telephone or mail.

6. In the 2004 federal budget, the government, accepting recommendations from the Joint Regulatory Table (JRT), provided new funding that will allow the Charities Directorate, among other things, to increase its profile. The government has also accepted a JRT recommendation that every official donation receipt display the name and contact information of the Charities Directorate.

BOB WYATT

Executive Director, The Muttart Foundation, Edmonton, Alberta