The author wishes to thank the following for helpful comments on earlier draughts: Professor Walter E. Block, College of the Holy Cross; John D. Gregory, Editor, The Philanthropist; Dr. John C. Goodman, National Center for Policy Analysis; Professor Dwight R. Lee, Washington University; Dr. Gerald L. Musgrave, Economics America Inc.; Dr. Filip Palda, The Fraser Institute; and Professor Charles K. Rowley, George Mason University. He accepts full responsibility for any errors which may remain.

Introduction

Over the last five decades the welfare state in most western democracies has expanded very rapidly. In Canada it has grown at an unprecedented rate since the early 1960s. Professor Herbert Grubel of Simon Fraser University found that total government spending as a per cent of Gross National Product (GNP) grew from 30.3 in 1961 to 41.1 in 1980. He writes: ” … over 40 percent of the increase in these expenditures can be explained by the growth in spending on social welfare”. He also found that, accompanying this explosion in welfare transfers, Canada has experienced “a pronounced downward trend in real income growth per person.”l

One widely accepted justification for the welfare state is that it will promote greater equity in the socioeconomic structure by more evenly distributing the nation’s wealth through transfers of income from those who have been graced by good fortune to those who have not. In this article we shall examine the degree to which democratic society has become egalitarian under the welfare state, and whether the observable problems it has experienced in aiding the truly unfortunate can be blamed on a lack of tax-based funding for state-run social services. We shall also examine the democratic political process and its possible impact on the way the welfare state functions. Finally, we shall consider perhaps the most fundamental program of the standard welfare state-socialized health care-with a view to discovering the degree to which real-world government-sponsored social welfare programs actually live up to their egalitarian justification and whether the needs of the truly impoverished would not be better served by private charity.

Examining the Record

Professors Webb and Sieve have extensively investigated income redistribution in Great Britain with the stated purpose of showing the effectiveness of the welfare state.2 Their findings were not supportive, however. They write:

Compared with 1939 … there is good reason to assume the degree of inequality had not changed by 1959. Therefore, the estimated inequality of final incomes remained constant over a period of twenty years which saw the establishment and growth to some stability of the Welfare State.

The overall changes between 1961 and 1969 amounted to an increase in the progressive effect of taxation, offset by a regressive change in the magnitude of benefits. (p.109)

Later, they conclude:

… Considering only the more redistributive of the fiscal and social welfare systems on the basis of a favourable selection of all welfare policies during a period widely acclaimed as egalitarian, we have seen that our society has remained fairly consistently unequal. (p.116)

In his 1973 version of The Charity of the Uncharitable, Professor Gordon

Tullock responds to Professors Webb and Sieve. He states:

Granted the massive amounts of income transferred back and forth through the population by the British government, it is clear that the major effect, and probably the major purpose, of this transfer cannot be to help the poor. With well in excess of 30 per cent of the average individual’s received income taxed away in one form or another and the defense burden much lower as a part of GNP than it was in 1937, it is clear that there are massive resources available for aiding the poor if that was indeed the objective of the British government.3

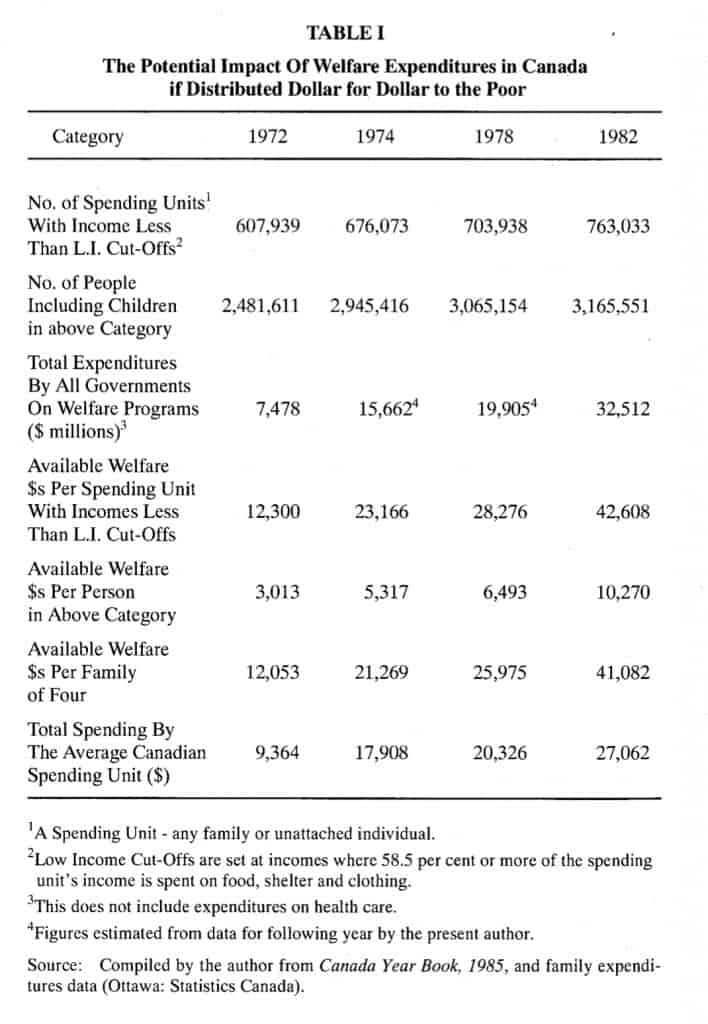

Professor Tullock’s observations do not apply to Britain alone. They describe equally well the situation in Canada and the United States. TABLE I shows welfare expenditures (excluding health care) made by all governments in Canada for selected years. As a proxy for the poverty threshold we use Statistics Canada’s rather arbitrary Low Income Cut-Off figures.4

As a measure of the poverty threshold, however, the Low Income Cut-Offs significantly overestimate the number of the truly impoverished. In a speech to the Ottawa Economic Society, Fraser Institute Director Dr. Michael Walker addressed the issue of mismeasurement of poverty in Canada:

… Statistics Canada, unlike many people who use the statistics, are quite careful to say “the cut-offs are not poverty lines and should not be so interpreted. The setting of poverty lines necessarily involves a value judgement as to the minimum income, below which an individual or family would generally be regarded as poor. No such judgement has been attempted now or previously in constructing the low income cut-offs” … The low income cut-offs do not take into account a number of important factors, such as wealth, access to subsidized goods and services, future earnings potenti.a1 , etc.s

Low Income Cut-Offs include many families and individuals who are not poor.6 Thus, the dollar amounts listed in rows 4, 5 and 6 of TABLE I show a distinct bias in favour of government welfare spending since the number of poor people implied by the Low Income Cut-Offs is exaggerated. Essentially, the money available for relief to the truly poor (if it were actually distributed to them) is far greater per poor person than TABLE I indicates.

Nevertheless, if government welfare dollars had been distributed evenly amongst all spending units which had incomes that fell below the Low Income Cut-Offs, each of those spending units would have received an astounding $42,608 in 1982. This means that every man, woman, and child officially designated as below the Low Income Cut-Off levels could have received $10,270 if this money had been divided evenly among them. Similarly, a family of four within this category could have received $41,082 in 1982.

In 1982 the average (or typical) Canadian spending unit spent only $27,062 on all goods and services. Clearly, it is well within the State’s power to raise the standard of living of the “poor” to at least that of the average Canadian spending unit. Indeed, to do this would require only 63.5 per cent of the money the government actually spends on welfare programs.7

It is realistic to suppose that the minimum requirement of Canada’s tax-funded welfare system is to ensure that the income of all citizens is at least as high as the “poverty threshold”. As the data show, Canada’s welfare system is financially more than capable of fulfilling this minimum obligation.s The obvious question, considering the number of impoverished people who exist in our society, is: What is the State doing with our money?

A similar situation exists in the United States. “The evidence is strong”, writes Professor Dwight R. Lee of Washington University, St, Louis, “that government transfer programs have failed”.9 In 1982 government welfare expenditures in the United States amounted to more than $403 billion. This was the equivalent of $11,730 per officially-designated poor person, or $46,9:20 for each poor family of four. Yet as Professor Lee points out, since 1973 there has been a persistent increase in the number of poor people as measured by the Bureau of the Census even though overall spending for poverty programs continued to rise during the 1980s.

In an article on welfare spending in the United States, Jonathan R. Hobbs writes:

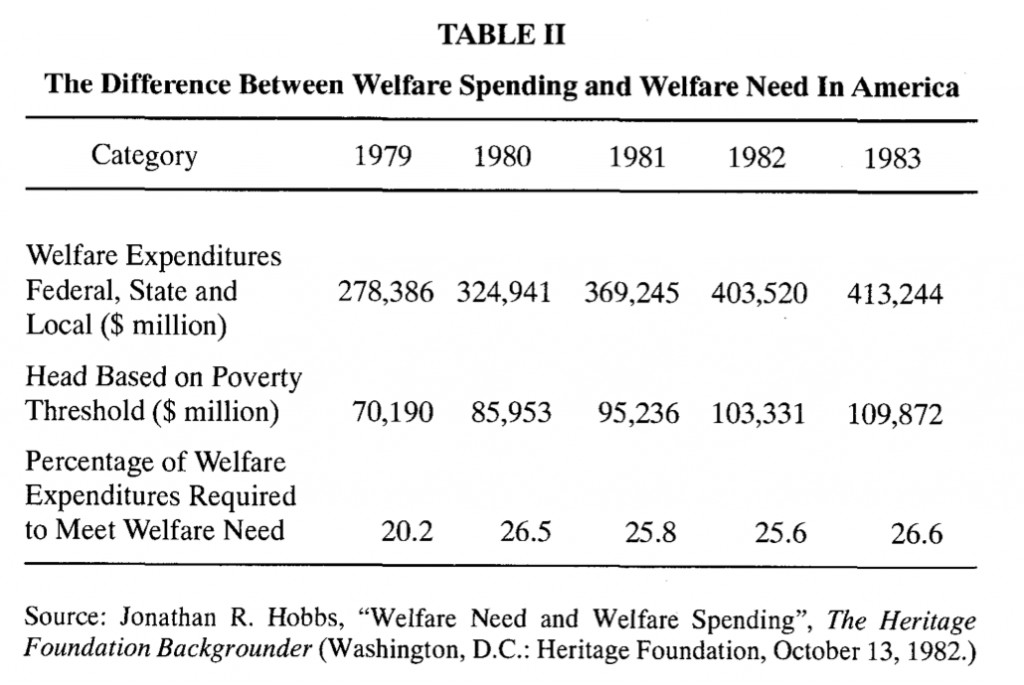

… [b]ased on the latest available census data, $101.8 billion, properly distributed, would have raised to the poverty threshold in 1982 the incomes of all Americans whose pre-welfare incomes were below the threshold. Allowing 1.5 percent-the Social Security Administration’s rate-for administrative overhead, it would have been<fossible officially to eliminate poverty in the United States at a cost of $103.3 billion.1

What is truly shocking about these facts is that the $103.3 billion needed to eliminate poverty represents only 25.6 per cent of what the U.S. government actually spent on welfare programs in 1982. Nor is this an isolated case for it is consistent with the findings from other years, as shown in TABLE II.

The evidence is clear: the welfare state in Canada and the U.S. has not met the egalitarian objective of its promoters. Nor can these people legitimately argue that the welfare state’s failure to eliminate poverty is due to a paucity of tax-based funding. Some very serious questions must be raised about the actual purpose of the welfare state. The government could totally and almost effortlessly eliminate poverty if it distributed even a fraction of the resources it collects, under the guise of relief to the poor, to those truly in need. But, as Jonathan R. Hobbs aptly puts it:

The industry [the welfare/social services industry] has demonstrated that its goal is not to eliminate poverty, but to expand welfare through increased spending, more benefits and programs, centralization of control in the federal government, and expanded employment in welfare-related services. 11

In discussing this, Professor Lee writes “predictably, the blame for this blatant failure seldom cuts to the fundamentals of the problem: a realistic assessment of the political process”.12 He further states:

. . . [e]ven those most critical of the government welfare programs seldom see the problem as inextricably tied to the political process. Favourite targets are fraud and corruption that should be rooted out with tighter controls over existing programs. Others see the solution coming from reforming existing programs …. But such calls for reform have been made for decades, and they have always been rendered politically impotent. In any event, welfare fraud can account for only a small amount of the cost of our welfare industry. And given the outpouring of scholarly articles on the poverty question, it is difficult to argue that the failure of our poverty programs can be reversed with yet more advice on desirable reforms.13

The Process and the Problem

The welfare state’s failure is imbedded in the nature of the democratic political process. Indeed, because of the character of predictable voting coalitions in a democracy, the presumed objective of the welfare state, i.e., social equality through forced income redistribution along the income continuum, cannot be realized. Transfers of wealth large enough to authenticate the welfare state’s egalitarian image will not be directed to the poor in a democracy such as ours. This conclusion is inescapable if we apply the same kind of rigorous examination to the political process that economists apply to the market.

Two popular theories are used to explain the emergence of the welfare state in a modern democracy. Professors James Roger and Harold Hochman postulate that the wealthy use the political process, and the state apparatus, to make charitable contributions to the impoverished.14 Professor Anthony Downs contends that in a democracy the poor have some degree of political power and are able to use their voting rights to acquire income transfers from the nonpoor.15 The two theories are frequently combined into the notion that the majority of the members of a democracy use the state apparatus to transfer wealth from the rich to the poor. This is very similar to the predominant argument used by proselytizers citing the virtues of the welfare state: the majority wishes to see a more “equitable” society, therefore an egalitarian redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor must be enforced via the welfare state.

These notions regarding the emergence of (or justification for) income redistribution in a democracy, however, fall short of explaining most observable welfare state activity. “They explain a small amount of it”, writes Professor Gordon Tullock, “but most redistribution comes from other motives and achieves other ends.”6

How can this claim be substantiated? To begin with, Professor Downs’ theory does, to a degree, reflect reality. The poor do have the right to vote, thus at least a portion of the transfers they receive can be attributed to their direct participation in the political process. In this sense the poor have some political power, i.e., their political power may produce some of the transfers they actually receive. However, the impoverished tend to be a distinct minority in most industrialized democracies. Even if they amount to 20 per cent of the population, their political power would still not be sufficient to bring about the emergence of the welfare state at the magnitude that we see today. Thus, we must reject Downs’ theory as the full explanation for the emergence of the welfare state. Moreover, in those democracies where the poor constitute a significant proportion of the population, the Downs theory leads us to predict that a substantial welfare state would emerge relatively early. This, however, does not seem to be the case. Thus, the element of truth embodied in it notwithstanding, the Downs theory is not a sufficient explanation for the emergence of the welfare state in any contemporary democracy.

Finally, if the combination of the Roger/Hochman theory and the Downs theory accurately explains the existence of the welfare state then we would predict a constant, continuous, and substantial redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor in a democracy such as ours. This is contrary to even cursory observations. Indeed, the transfers that are made to the poor are relatively small in all democracies.17 Consequently, it is extremely questionable to assert that the welfare state exists because it is the objective of the majority of the population to achieve greater social equity by redistributing income from the rich to the poor.

The Downs model implies that redistribution takes place along a continuum in which people are arranged from poorest to richest. This component of the model helps to explain the emergence and apparent weakness of the welfare state. 18

Initially, two scenarios for the evolution of mandated wealth redistribution seem plausible. First, it is conceivable that a coalition of the bottom 51 per cent (in terms of income) of the citizens, using their majority, could impose a welfare state to take money from the remaining (upper income) 49 per cent. Alternatively, a coalition of the top 51 per cent could use their majority to take money from the remaining (lower income) 49 per cent.

Either outcome seems equally likely at first consideration. “Indeed, the two percent of the population lying at the middle line would be the determining factor in such a choice, hence we might anticipate that money would come from both ends to the middle”.19 This middle two per cent can form a voting coalition with either the top 49 per cent or the bottom 49 per cent of the income continuum. The logical conclusion is that this middle two per cent would, as much as possible, support both. By playing one against the other the median two per cent could potentially create a situation where they occasionally acquired income transfers from both the top and the bottom.

But with whom is this powerful two per cent most likely to collude? It is obvious that the upper 49 per cent have more wealth than the bottom 49 per cent. It follows that, relative to the bottom 49 per cent, the rich have more money available to be taxed. Therefore, when establishing a voting coalition for the purpose of transferring income away from the 49 per cent of the population who do not belong, it is relatively more costly for the group to admit members from the upper 49 per cent to the exclusion of potential members from the bottom 49 per cent than vice versa.

It is in the interest of the voting coalition to have a tax base with a maximum amount of wealth. “One would therefore anticipate”, writes Professor Tullock, “that voting coalitions would be made up in such a way as to minimize the number of wealthy members. This is, indeed, the element of truth in the Downs model … “20 The dominant voting coalition in a democracy, at least with respect to wealth redistribution along the income continuum, is going to be the bottom 51 per cent of voters on the income continuum.

This, however, does not give us any indication of how the coalition will distribute its received income transfers. The usual justification for the welfare state is redistributing income from the rich to the poor. Yet, there is nothing in the voting coalition structure that guarantees the transfers will actually reach the poor. Even if we assume that 20 per cent of the total population is poor they would still only make up 40 per cent of the dominant voting coalition. Thus, even under the most generous assumption, the poor can have no substantial power in the coalition and they certainly cannot dominate it. What possible reason do we have to believe that the poor, who are a clear minority, will receive the bulk of the transfers? If the poor do receive more income transfers than the rest of the coalition then they do so only because of the generosity of the lower middle class, i.e., those voters between the 20th and the 51st percentile of the income continuum.

The egalitarian case for the welfare state must therefore rest on the assumption that the lower middle class is generous. If this assumption is true, however, it does considerable damage to another important canon assumed to justify forced income redistribution: the rich are selfish and will not voluntarily distribute some of their wealth to the poor. If the lower middle class is not selfish but instead charitable towards the poor-and it must be if the democratic welfare state is to meet its supposed objective according to our model-then there is every reason to believe that the upper middle class and the wealthy are also charitable, i.e., those voters between the 51st and 99th percentile of the income continuum. This follows simply because they have more with which to be generous.

We observe a major inconsistency in the case for the welfare state if its real goal is the betterment of the poor. The justification for mandatory wealth redistribution from the rich to the poor in a democracy rests on two apparently conflicting and irreconcilable assumptions. First, the lower middle class must necessarily be generous toward the poor, and second, the upper middle class and the wealthy must necessarily not be generous toward the poor.

We should not be surprised by the failure of the democratic welfare state to aid the genuinely poor. Indeed, when formal bargaining theory is used to analyze forced wealth redistribution from the rich to the poor, this is a predictable result. In a democracy, any system that forcibly transfers income along a continuum must provide the top portion of the dominant voting coalition, i.e., the people between the 20th and 51st percentile of the income continuum, the lower middle class, with at least as much as it provides the poor. If this is not the case, the top portion of the lower middle class, the powerful two per cent, will be inclined to realign themselves in a new coalition with the voters in the upper 49 per cent of the income continuum.

This will occur for two reasons. First, voters in the upper 49 per cent of the income continuum can arrange to redistribute less of their wealth. Second, the powerful two per cent can arrange to receive all income transfers made by the welfare state.

It is in the interest of the upper middle class and the rich to buy out the middle two per cent for some amount marginally greater than the amount the middle two per cent get from their share of transfers under the existing system. Furthermore, the buyout price would be considerably less than the amount of income taxed away from the upper middle class and the wealthy for redistribution by the potential coalition of the lower 51 per cent.

The upper middle class and the rich-the upper 49 per cent of the income continuum-are motivated to do this because once the new coalition is established it will have the voting power to cut off all transfers of income (except those motivated by generosity) to everyone but the powerful two per cent. By so doing, voters in the upper 49 per cent of the income continuum save a substantial amount in tax payments. The powerful two per cent are motivated to accept the bribe and realign themselves because they can obtain larger payoffs from the new alignment than through the original coalition.

Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that the new voting coalition would take the entire transfer, i.e., the middle two per cent’s bribe, out of the pockets of non-members of the coalition: the bottom 49 per cent of the income continuum.

The threat of such a voting coalition realignment always exists in a democratic welfare state. It becomes inevitable, however, anytime the lower middle class, especially the powerful two per cent, receives a marginally smaller share of the income transfers than do the poor. Consequently, for the democratic welfare state to transfer any amount of wealth to the poor at all, it will always be the case that the lower middle class and especially the powerful two per cent will receive the bulk of all transfer payments. This is a rather gloomy prospect given the assumption that the intended purpose of the welfare state is egalitarian.

There is, however, one possible method of ensuring that income transfers are delivered to the poorest members of society. This is a voting coalition between the wealthy and the very poor. In discussing this Professor Tullock writes:

… [i]n the real world, we see signs of such coalition attempts. Among people who argue that all transfers should be strictly limited to the very poor by a stringent means test, it is likely that wealthy persons predominate. This is, of course, sensible from even a selfish stand point. They could arrange to give the present-day poor considerably more money than they are now receiving, in return for a coalition in which transfers to people in the upper part of the bottom 51 per cent are terminated, and make a neat ‘profit’. This particular coalition has so far foundered largely because of miscalculations by the poor. They realize that the interests of the wealthy are clearly not congruent with their interests, but they do not realize that the interests of the people between the 20th and 51st percentile of income distribution are not identical with theirs. They therefore tend to favour a coalition with the less poor rather than with the wealthy.Z 1

The possibility and even probability of such a coalition provides a strong argument for a voluntary system of income redistribution. To be more precise, this coalition is the best option of the given options for both the poor and the rich. Since it is beneficial to both, we predict that each will display a preference for it. In the sense that any mutually beneficial displayed preference is voluntary, the decision of the rich and the poor to collude in this fashion would be a voluntary one.

Such a coalition will emerge independently of a welfare system imposed by the state. State-enforced income redistribution, by its very nature, results in voting coalitions between the poor and the lower middle class or the previously described coalition between the rich and the powerful two per cent. Because of the nature of predicted voting coalitions, it is logically impossible democratically to create and enforce a mandated wealth redistribution system which includes only the rich and the poor.

If the poor represent 20 per cent of the population and the rich represent ,20 per cent of the population (a highly exaggerated scenario) then their voting coalition can, at best, command only 40 per cent of the voting power. If such a coalition attempted democratically to impose a state-directed income redistribution policy rather than one which was private and voluntary, their attempts would be usurped (through the democratic process) by the powerful middle class. That is, the lower middle class, not wanting to lose its windfall transfers, will collude with the upper middle class and dominate the voting process in such a manner as to ensure that the lower middle class receives marginally greater transfers and the upper middle class suffers a marginally smaller tax burden. For that matter the upper middle class could enjoy some of the transfers themselves if the coalition chose to impose the full burden of the tax on the rich as well as eliminating transfers to the poor.22

This makes a good case for the emergence of private voluntary charity as an alternative to, and independent from, the democratically created and enforced welfare state. Moreover, it provides significant theoretical substance for the argument that the only successful method of income redistribution from the rich to the poor is private charity. Professor Tullock lends further clarity to this notion. He writes:

… it seems likely that only the generally bad information and low IQ and/or motivation which we observe among the poor prevents such coalitions. Indeed, it is possible that the poor would do better if they depended entirely on the charitable motives of the wealthy. It might be that … [a wealthy person] … if left entirely to himself, would be willing to give … [a poor person] more than $250, although he objects to spending $500 for $250 apiece to … [a middle income person and a poor person]. Most people, after all, are to some extent charitable and it may wellbe that the very f:oor would do better than at present if they depended on the charity of the wealthy. 3

The democratic political process has an impact on the way the welfare state functions. Specifically, if the real objective of social welfare programs is forcibly to transfer income from the rich to the poor, then we predict that the dominant voting coalition to emerge will be one that will have little or no incentive to direct the bulk of income transfers to the poor.

Powerful Middle Class Interests

The generally stated justification for the welfare state is based on a misunderstanding of the political process and aspires to an impossible objective since the interests of the middle class will control most transfers of wealth.

In the preceding theoretical investigation we assumed that income redistribution occurred between income groups along the income continuum. As Professor Tullock points out, however:

… [i]n the real world, we observe that the bulk of transfers are made to groups not defined by income. Farmers, university students, older people and other “welfare” beneficiaries regardless of their income, and, probably the intellectual class are the main recipients of transfers, even though the bulk of these groups are not poor. 24

There are, indeed, massive income transfers via the political process, “but they are not in the main transfers of funds from the wealthy to the poor, but transfers of funds among the middle class”.25 The majority of the income redistribution achieved via the welfare state takes place between the 20th and 90th percentile of income. This group has the largest tax base and also represents the greatest concentration of political power in a democracy.

In reality, despite the egalitarian arguments frequently used to justify forced income redistribution, the welfare state cannot be said to exist as a “safety net” for the poor. It is more useful to consider the “egalitarian motive” as a strategically placed smoke screen to camouflage the motivations of many well organized, and politically powerful, middle class interest groups.26 To the degree that the impoverished are poorly organized-perhaps because they mistakenly feel that the middle class truly has their interests at heart and thus believe they don’t need to organize-the poor are unlikely to be successful at gaining sufficient political power to secure large wealth transfers through the democratic welfare state. Professor Tullock writes of this:

… [i]f the real world is one in which transfers are made to organized groups, which receive their transfers largely in terms of their political power, there is no reason why we should anticipate that the poor would do particularly well. For one thing they are hard to organize. Thus, the very large transfers that we do observe in the world …

only accidentally benefit the bottom 10 to 15 per cent of the population … 27

Canada’s welfare state is anything but egalitarian. Contrary to popular myth, it does not aid the poor in any substantial way; rather it predominantly aids the politically powerful special interest groups of the middle class. The transfers that we do see primarily take place within the middle class, and tend to go to people who have political power and come from people who do not.28

Socialized Health Care

There is ample empirical evidence to support these claims. For example, socialized health care is one area where the welfare state falls far short of its egalitarian image. In Canada, Great Britain, and the United States, according to the evidence, the introduction of socialized medicine actually harmed the poor.29

Health Care In Canada

In 1977, 733 medical doctors emigrated from Canada to the United States. As well, many medical students studying in Canada indicated their intention to move to the U.S. after graduation.30 This is not surprising considering the real income of Canadian physicians declined by 40 per cent from 1971 to 1975 but that of U.S. doctors was rising significantly.

This continued loss of medical resources gives us good reason to suspect that free and easy access to health care in Canada is not being increased under Canadian National Health Insurance (CNHI). Indeed, Professors Cotton Lindsay and Arthur Seldon found that the introduction of CNHI ” … has made health care harder to get for large numbers of Canadians, principally those living in already under-doctored areas, and that it has shifted a large portion of the cost of the nation’s medical care onto the shoulders of people with lower incomes”.31 They further state:

… [a] market pricing structure provides that physicians who practice in unattractive, poor, remote locations earn more than their colleagues who prefer to practice in attractive urban settings. When fees are equalized across entire provinces as under CNHI, the inducement to practice in less attractive areas is eliminated. Fewer physicians will choose to practice in less amenable communities since a particular service commands the same fee regardless of where it is delivered … In the long run, the reimbursement system adopted by all provinces provides monetary incentive for physicians to spurn the ghettos and the hinterlands and to practice in urban environments already richly endowed with medical manpower. It matters little that there is no price barrier if there is no doctor. As a result of the reimbursement system adopted by CNHI, doctors are simply moving away from the poor.

Professors Lindsay and Seldon analyzed data on the number of Canadian medical doctors practising in 1965 and compared it to the number of medical doctors practising in 1975.32 Their rigorous statistical analysis revealed that between 1965 and 1975 the importance of urbanization as a factor in doctors’ choice of location had increased by 70-75 per cent. They found that during this period the general physician-to-population ratio increased by 33 per cent in the province of Quebec as a whole; however, it increased by only 7.3 per cent in the 10 least urbanized counties.33 In other words, the growth in available doctors per capita was slower, by a factor of 10, in the poorer regions of Quebec than it was in the rest of the province during the decade immediately following the introduction of socialized medicine.

Many Canadians erroneously believe that socialized health care offers them something for nothing. There is seldom any direct personal expense involved in a visit to the doctor so people often begin to think of it as “free”. But as Professors Lindsay and Seldon tersely note:

… [o]ne of the most important lessons that economics teaches is that, while one person may get something for nothing (by taking it from someone else), it is impossible for everyone to have something for nothing. For each person who gets something for nothing there must be someone else who gets nothing for something?4

Health care under the Canadian system may appear “free” but it most certainly is not. Ignoring the obvious increase in the tax burden associated with socialized medicine, there are less obvious costs such as increased waiting times for service. When there is no exclusion through price there will be an increased demand. If this increase is not matched by an increase in provision or production then consumers will not be able to consume the good or service on demand but will be forced to wait.

Indeed, even though the number of doctors was increasing in Quebec at the time, the waiting time for an appointment increased on average from six to 11 days immediately following the province’s entry into the national health insurance program.35

This problem has continued to worsen to the point where patients needing to see a specialist must wait as long as half a year or more. In Victoria the current waiting period for non-emergency day surgery, where no hospital bed is required, is six months. In cities like Vancouver and Toronto the waiting period can be as much as a year. Canadian patients requiring emergency cancer and heart surgery are regularly shipped off to U.S. hospitals because a hospital bed cannot be found for them or a surgeon skilled enough to do the surgery is not available.

Even though Canadian health care workers are considered the most highly skilled in the world there is simply not enough of them, or of the necessary support facilities, to meet the demand. In essence, because access is free, the increased burden placed on the health care system for minor, incidental, or nonexistent health problems (things which would ordinarily be ignored) has resulted in malinvestment in the whole system, i.e., the financing of relatively insignificant demands has crowded out the financing of significantly more important health care needs.36

So who pays for Canada’s national health program? When the program was adopted it was not accompanied by a special tax to finance it. Furthermore, aggregate government spending did not rise by the full cost of the program. “If spending on health programs is not accompanied by corresponding expansions of the total budget”, write Professors Lindsay and Seldon, “the conclusion seems inescapable that some older programs have been cut to finance CNHJ.”37

Indeed, this is what happened, but the choice of programs that were cannibalized is rather shocking. To finance both the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services (HIDS) Act and the federal Medical Care Act [both replaced in 1984 by the Canada Health Act, R.S.C. 1985 c. C-6] funds were diverted, in substantial amounts, from existing social welfare programs that were supposedly designed to aid the poor. Professors Lindsay and Seldon write:

… [t]aken together, both parts of CNHI seem to have been financed largely through reductions in social welfare spending … roughly sixty cents out of every dollar spent on

CNHI would otherwise have been spent on social welfare programs …. First, we can state categorically that the social welfare programs bearing the brunt of CNHI financing did not represent social financing of medical care which was phased out or administratively moved due to the introduction of CNHI. Pains were taken to purge from these data any spending for health care under the category of social welfare. Our estimates thus can not be dismissed as merely identifying an accounting shift which moved dollars spent on medical care from one program to another …. In the name of extending … medical care to all, the rich as well as the poor, the Canadian

government has shifted the burden of financing most of it onto the poor. 38[Emphasis

added.]

Health Care In Great Britain

In 1948 the British National Health Service (NHS) came into existence. Its proponents made the bold promise that it was ushering in a new era where everyone would have unlimited free access to the highest quality health care.

They must have been excluding the poor from this promise, however, for the evidence shows that the poor began receiving less and lower quality health care promptly after the NHS was established. “In the 10 years following the enactment of this measure”, writes Professor Tullock, “the death rate among the poorest portion of the British population increased, in spite of the fantastic technological improvements in medicine during this period”.39

During this period the overall death rate was dropping. But even after the NHS was well established the death rate of the poor continued to rise. Professor Lee writes:

… [t]he male mortality rate for unskilled workers was 16 percent higher for the years

1970-72 than it was for the years 1949-53. This contrasts with the decreasing mortality rates for all other classes of British males over the same period. For example, over the interval 1949-53 unskilled male workers had a mortality rate 37 percent higher than did professional male workers, but by 1970-72 the mortality rate of unskilled workers was 78 percent higher than that of professional male workers.40

Professor Gordon Tullock41 offers a hypothesis to explain this most unfortunate situation. Prior to 1948 the poor received free, or at least close to free, health care through public and private charities that directed their services specifically to the needs of the poor. The rest of the people of Great Britain paid for their health care. The rich paid for themselves and the middle class paid through various insurance programs. Because they paid for it, however, both groups used health care services sparingly. With the introduction of the NHS, medical services became free for all British citizens. This resulted in increased consumption by the middle class and the rich.

The total amount of medical resources did not increase at a proportionate rate to the demand. Cotton Lindsay and Arthur Seldan corroborated this in their study. They write, ” … the apparent result of government medicine in the United Kingdom has been a net reduction in the resources channelled to health care.”42 In total contradiction to what NHS proponents had long promised-a more equitable distribution (geographically) of hospital services-for the first

10 years of the NHS no new hospitals were built in Britain. Even 20 years after

NHS was introduced the government had done little to fulfil its promises.43

In effect, the increased use of medical services by the non-poor crowded out, and continues to crowd out, the poor.

The poor are crowded out for a number of reasons. To begin with, when the program first emerged it radically changed the way doctors were paid and had the effect of reducing their incentives to work with the poor. It rewarded doctors marginally more if they redirected their practices toward people with a relatively light incidence of disease. This translated into a movement away from the poor, a problem which continues today.

As well, because health care is limited at zero price to less than the population wants, it must be “rationed” by the NHS authorities. Contrary to the official line, “rationing” has never been done on the basis of medical need, rather, political influence, community standing, and personal contacts emerged as important criteria. This situation obviously favours the non-poor over the poor. Richard Titmuss, who has been called the Godfather of NHS, spoke of this very thing in 1968 when he said:

… the higher income groups know how to make better use of the NHS. They tend to receive more specialist attention; occupy more of the beds in better equipped and staffed hospitals; receive more elective surgery; and better maternity care, and are more likely to get psychiatric help than low income groups-particularly the unskilled.44

So the rise in the death rate of the poor in Britain after the introduction of the NHS, a program broadly acclaimed as the most egalitarian public health system in the world, should not be a surprise. Indeed, it seems quite predictable when the scheme is thoroughly examined. Here again, if we subscribe to equity, we are forced to question the motives of those who support the NHS. As Professor Tullock writes:

… the advocates of the NHS who may have aimed to aid the poor evidently did not understand what they would be doing, since it clearly did not increase the resources available to them. Must the observer conclude that they intended to benefit the middle class-which, in the event, they did? It was probably a most inefficient method of transferring resources from the poor to the middle class. (A good economist could have given advice on better techniques to those who wished to grind the faces of the poor!)45

Health Care In The United States

In 1965 the United States government introduced Medicare, a non-meanstested subsidized health program for those over 65 years of age. Medicare is also not a transfer from the rich to the poor.

On average, those over 65 are better off than those under 65. In 1980, the after-tax income of the elderly averaged $6,300 per capita but the after-tax income of the non-elderly was only $5,910 per capita.46 Furthermore, the elderly may have more assets: they often own their homes outright, and may have income-earning investments. This is not generally true of the young and it is particularly not true of the working poor. Medicare cannot, therefore, be seen as an anti-poverty program.

Nor can it be argued that the beneficiaries of Medicare have either earned or paid for the services they receive. It is true that Americans pay a marginal tax throughout their lives which is designated for Medicare but this comes nowhere near to covering the benefits received after age 65. In the mid 1980s, typical middle class Americans who had earned an average income drew more benefits from Medicare, within two years of retiring at 65, than they paid into the program over their entire working lives. Even if we assume the unlikely case that the cost of medical services does not rise in the United States, people earning average incomes can expect to receive Medicare benefits (from retirement to death) worth $27,000 more than they have ever paid in. If these people have spouses who did not contribute, this figure approaches $60,000.47

This has very interesting implications for minorities in America (the minority groups, especially Blacks and Hispanics, are amongst the poorest people in the country). As of 1984, health statistics from the National Center for Health showed that a newly born black male had a life expectancy of only 64.8 years. This means that he will, in all probability, die before he reaches the medicare eligibility age of 65, even though he will have paid taxes into the program throughout his working life.

The situation could be even more tragic, however, if Congress follows through with the recurring recommendation to raise the Medicare eligibility to age 67 and to index it as well. This would mean that every time an increase in general life expectancy was perceived, the eligibility age for Medicare would also rise. The consequences of this proposal would be devastating for the poor since their life expectancy would never catch up regardless of advances in medical technology. “They will never,” writes John Goodman,48 “be able to reach the point on average where they could expect to receive net benefits from the system. About 14 per cent of the tax paying population is nonwhite, but fewer than nine per cent of the Medicare beneficiaries are nonwhite.” He further states:

… [m)edicare is a system which takes billions of dollars from the working population and hands it over to people who by and large are not working. It gives billions of dollars in medical benefits to people who did not earn those benefits and have no reason to claim entitlement to them. It takes taxes away from the working poor to pay the medical bills of retired millionaires. This system is basically unfair ….

“The notion that the elderly are poor is wrong”, writes leading health care economist, Dr. Gerald L. Musgrave, “[i]n fact, those over 65 earn more than those under 25. The elderly earn more than the working young in our nation, and in every region. These numbers are before taxes! Since income includes Social Security payments which are largely exempt from taxation, the real spendable income of the elderly is very large in comparison to the working young.”49

Examination of the effects of subsidized medical care in Canada, Great Britain, and the United States leads inevitably to the conclusion that socialized medicine is anything but the egalitarian idea that its supporters believe it to be. Indeed, if the creators of these programs had actually set out to devise schemes to covertly harm the poor, they could not have done a better job. In the words of Cotton Lindsay: “[l]ong before governments took an active role in this area churches and charitable groups cared for the poor. I have seen no evidence that their health or anyone else’s is better served now by our own or any other form of government medicine.”50

Conclusion

The Third Sector may provide us with an alternative to the welfare state. Perhaps if income redistribution actually were directed from the rich to the poor (assuming that this is even possible in a democratic political system such as ours) and performed the miracle of social equality that those who promote it claim it does, we might be inclined to modify our conclusion.

Facts are facts, however. We do not see, in any substantial way, the poor being aided by the welfare state.Sl Nor is this failure the result of underfunding. Indeed as the evidence clearly shows, funding for welfare programs is far in excess of that required to eliminate poverty entirely in both Canada and the United States. Furthermore the program considered to be the greatest help to the poor-socialized health care-is actually a disservice, even a deadly disservice, to the poor. We must conclude that the welfare state, as we know it, has failed to meet its stated egalitarian objective.

But more to the point, it is the nature of the democratic political process that forced income redistribution will work against the interest of the poor. This fact supersedes attempts to implement strict means testing and greater system efficiency in welfare programs; they are ultimately rendered fruitless. It is reasonable to conclude that the poor would be much better off under a system of voluntary charity than they ever will be under a democratic welfare state.

FOOTNOTES

1. Herbert Grube], “The Cost Of Canada’s Social Insurance Programs”, in George Lermer, Probing Leviathan: An Investigation of Government in the Economy (Vancouver: The Fraser Institute, 1984).

2. A.L. Webb and J .E.B. Sieve, “Income Redistribution And The Welfare State”, Occasional

Papers on Social Administration No.41 (London: Bell, 1971).

3. Professor Tullock states that the comments made by Professors Webb and Sieve are “particularly revealing since both are vigorous advocates of the British Welfare State and the subject matter of their book is the improvement of statistics on its effects”. (Note 5, p.18)

“The Charity of the Uncharitable” first appeared in the Western Economic Journal, December 1971 and was considerably revised and enlarged into a chapter for the Institute of Economic Affairs Readings #12, “The Economics of Charity” 1973, from which quotations in this article are taken.

4. Low Income Cut-Offs are used by Statistics Canada to distinguish between low income family units and other family units. They are determined separately for family size and degree of urbanization. The settings are arbitrary and are revised from time to time as the proportion of income the average Canadian family spends on food, shelter, and clothing, changes. The Low Income Cut-Off is now set at an arbitrary 58.5 per cent (of income spent on food, clothing, shelter). The Statistics Canada 1985 Canada Year Book estimates that about 12 per cent of families and about 37.8 per cent of all unattached individuals are within this category. (Canada Year Book 1985, p.170 and Table 5.36.)

5. See “The Mismeasurement Of Poverty In Canada”, a speech by Dr. Michael Walker to the Ottawa Economic Society, Ottawa, Ontario, March 20, 1986, The Fraser Institute.

6. Moreover, as Dr. Walker points out, by frequently used definitions of poverty, there will always be some people considered to be within the “poor” category regardless of how prosperous they really are. In his speech he notes that “Canadian poverty measures have tended to rely on relative concepts of poverty, that is to say defining the poor in comparison with the average income of Canadians, or by using some other statistical measure of where the population is on the income scale. In that sense the Biblical phrase

‘the poor you have always with you,’ acquires particular significance and poignancy since

the very measurement of who is poor insures that will be the case. This is not well appreciated, but once we accept relative poverty measurements, then we must also recognize that it is meaningless to think of eliminating poverty in this sense. It is quite impossible to eliminate it and quite meaningless to speak of a policy designated to eradicate it.”

7. Again, this figure would be even less than 63.5 per cent if the Low Income Cut-Offs did not exaggerate the number of poor people in Canada.

8. Dr. Michael Walker states: “[t]he question is not, ultimately, whether we can afford to provide more dollars for welfare spending and whether in that sense we are expending enough social welfare effort. To raise all Canadians above the poverty line as defined by the National Council on Welfare would require only a third of the money earmarked for social welfare spending.” (Fraser Forum, March 1987, p.7.)

9. Dwight R. Lee, “The Politics of Poverty and the Poverty of Politics”, CatoJournal, Vol.5, no.1, Spring/Summer 1985.

10. Jonathan R. Hobbs, “Welfare Need and Welfare Spending”, The Heritage Foundation

Backgrounder (Washington, D.C.: Heritage Foundation, October 13, 1982).

11. Ibid.

12. Supra, footnote 9, p.12.

13. Ibid., p.19.

14. James Roger and Harold Hochman, “Pareto Optimal Redistribution”,AmericanEconomic

Review, September 1969, pp.242-257.

15. Anthony Downs, An Economic Theory Of Democracy (New York: 1957), pp.198-201.

16. Tullock, supra, footnote 3, p.17.

17. Professor Tullock states, supra, footnote 3, p.17, “anybody examining the status of the poor in the modern world must realize that democracies do not make very large gifts to them”.

18. So far as it goes, this element of the Downs model is consistent with the standard egalitarian justification of the welfare state which necessarily assumes that income redistribution occurs along an income continuum with wealth being transferred from the rich to the poor. Because the egalitarian justification of the welfare state relies on this notion, the following analysis of voting coalitions of members of the continuum applies. For the purpose of our analysis it is not important whether or not redistribution actually does occur along a continuum. All that is important is that the standard justification assumes it does and that, based on this assumption, we can examine the voting coalitions that are expected to emerge.

19. Tullock, supra, footnote 3, p.19.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid., p.20.

22. Given this analysis, it is not surprising that in the real world of the democratic welfare state, by far the largest per capita recipients of all income transfers (both direct and indirect) are the middle class, i.e., people who are between the 20th and 90th percentile of the income continuum.

23. Tullock, supra, footnote 3, p.21, n.13.

24. Ibid., p.22.

25. Ibid., p.23.

26. This may read like a conspiracy theory but it is nothing so dramatic. I do not wish to imply that there were or are specific individuals who conspired to create a welfare system which would largely benefit the middle class. I argue only that, in a democracy such as ours, the political interests of middle class pressure groups will dominate simply because the middle class holds the bulk of political power.

27. Tullock, supra, footnote 3, p.22.

28. As the welfare state grows, the process just described becomes more and more evident.

A superb example of this is old age pensions expenditures in Great Britain which have grown massively and in the process have become less and less egalitarian. Professor C.G. Hanson alludes to the fact, perhaps unwittingly, that as the political stakes got higher in Britain, i.e., increased voter/taxpayer unwillingness to support constant and continued growth of the welfare state, politicians had to move from an egalitarian strategy to one that would appease the powerful middle class. He writes: “In the 1960s both political parties began to favour graduated, or wage related, state contributions and benefits. This means the better off pay more and receive more from the state. The policy of the 1908

Old Age Pension Act, under which money was transferred from the wealthy and the working generation to the elderly poor, has been practically stood on its head: the State now promises the largest pensions to those who are manifestly capable of providing for themselves if they wish to do so.” See p.138, C.G. Hanson, “Welfare Before The Welfare State” in The Long Debate On Poverty (London: The Institute of Economic Affairs, Readings #9, 1974).

29. See John Goodman, “Solving The Medicare Crises”, Policy Report (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, February 1984); Cotton M. Lindsay, Canadian National Health Insurance: Lessons for the United States (New York: Basic Books, 1978); Cotton M. Lindsay, Government Medicine: The British Experience (Nutley, NJ: Roche Laboratories, 1979); and Cotton M. Lindsay, Ed. New Directions In Public Health Care: A Prescription For The 1980s (San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies, 1980).

30. Emile Berger and William Mosberg Jr., “Ten Years Of National Health Service In

Canada”, Neurosurgery, Vol.4, no.6, 1979.

31. Lindsay, New Directions, supra, footnote 29, p.77.

32. The years 1965 and 1975 were chosen so that comparisons between the pre-socialized medicine ratios and the post-socialized medicine ratios could be made. TheMedicial Care Act, S.C. 1966-67, c.64 [now replaced by the Canada Health Act, R.S.C. 1985, c.C-6] passed in 1966 but did not take effect unt1968 and then only in British Columbia and Saskatchewan. A year later Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia joined the program. It was not unt1971 that the program encompassed all the provinces when Quebec, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick joined.

33. Lindsay, New Directions, supra, footnote 29.

34. Ibid., p.78.

35. Ibid., p. 79. See also Philip E. Enterline, “Effects of Free Medical Care on Medical Practice: The Quebec Experience”, The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol.288, no.22, May 1973, pp.1152-55.

36. It should also be pointed out that lowering the direct monetary price of health care to zero, and the resulting crowded waiting rooms and huge appointment backlogs, places doctors in the position where they feel they must hurry their patients through. Furthermore, doctors are increasingly having support staff take on responsibilities and perform tasks that were traditionally done by the physician. This may reduce the quality of care, a cost that is very difficult to measure.

37. Lindsay, New Directions, supra, footnote 29, p.80.

38. Ibid., pp. 81-85.

39. Tullock, supra, footnote 3, p.25.

40. Supra, footnote 9, p.35.

41. Tullock, supra, footnote 3, p.22ff.

42. Lindsay, New Directions, supra, footnote 29, p.77.

43. See Michael Cooper and Anthony J. Culyer, Health Service Financing (London: British

Medical Association, 1970).

Many of the hospitals that were nationalized by the NHS were originally the products of great philanthropic gestures by the newly rich industrialists of the 19th century. Unfortunately, the locations chosen by the philanthropists generally coincided with the areas

I

II

Iii

1/:1

Iii

Ill

I,

II

they were familiar with and so the very poor parts of London and the industrial North seldom benefited from these gifts. There were some donated hospitals built in poor areas, however. Two very famous hospitals, the London-Teaching-Hospital and the charitable Jewish Hospital, were built in London’s East End. (Lindsay, New Directions, supra, footnote 29, p.84.)

The point here is that even though there was an imbalance in the distribution of hospitals under the philanthropic system of hospital provision, some charitable resources were still specifically designated for the treatment of the poor and there did exist a genuine concern for their welfare. Even the donated hospitals in the West End of London, which served many who were not poor, were still first and foremost charitable and made a special effort to help the poor. The same claim cannot be made for the hospital system after NHS was enacted. Indeed, Cotton Lindsay’s 1979 study (Government Medicine, supra, footnote

29) shows that the geographic distribution of hospital spending under NHS is, in a considerable way, determined by the localities’ political importance rather than considerations of equity.

44. Richard Titmuss, quoted in The Economist, Apr28, 1984, p.19.

45. Tullock, supra, footnote 3, at p.45.

46. John Goodman, “Solving The Medicare Crisis”, Cato Policy Report (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, February 1984).

47. Ibid., p.6.

48. Ibid.

49. From private correspondence, Musgrave to the author, July 26, 1988. The relative mean money incomes of working age people under 25 years compared to those over 65 years for 1986 (by region) are as follows: USA, <25=$18,155, >65=$19,816; North East USA,

<25=$20,134, >65=$20,278; Mideast USA, <25=$17,234, >65=$18,810; South USA,

<25=$17,267, >65=$18,574; West USA, <25=$19,142, >65=$23,144. See, “Money Income of Households, Families, and Persons in the United States”, Current Population Reports (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of the Census, June 1988) pp.26-27.

50. Lindsay, New Directions, supra, footnote 29, p.100.

51. There have been a number of scholarly studies in recent years that have addressed this issue. Consistently, these studies have found that the poor are made increasingly worse off as the welfare state grows. Some of these include: Martin Anderson, Welfare: The Political Economy of Welfare Reform in the United States (Stanford, CA.: Hoover Institution Press, 1978); Henry Hazlitt, The Conquest of Poverty (New York: Arlington House, 1973); Henry Hazlitt, Man vs. The Welfare State (Vancouver, B.C.: Mitchell Press Limited, 1971); John C. Goodman, Welfare and Poverty, Policy Report #107 (Dallas, Texas: National Center for Policy Analysis, 1985); John C. Goodman and Michael D. Strop, Privatizing The Welfare State, Policy Report #123 (Dallas, Texas: National Center For Policy Analysis, June, 1986); Lowell Gallaway and Richard Vedder, Paying People to be Poor, Policy Report #121 (Dallas, Texas: National Center for Policy Analysis, 1986); Charles Murray, Losing Ground: American Social Policy 1950-1980 (New York:

Basic Books, 1985); and Walter E. Williams, The State Against Blacks (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1982).

MARK D. HUGHES