Introduction

The selection of professionals to manage fund-raising programs is a key decision for trustees and executives of non-profit organizations. The expectation when hiring a fund-raising professional is for a quick as well as high rate of return on the investment, which is seldom the reality. The selection process should include a clear understanding of the relationship between fund-raising costs and the gift income received from each method used.

Fund-raising costs are a growing concern for all registered charities. Guidelines to compare money spent with gifts received are now available. Hiring a fund raiser can be one of the best of economic decisions since the rate of return (gift revenues) should exceed costs by four or five times after a three-year period. But waiting three years for results is too long. Use of these guidelines as well as clear specifications in the job contract can enable trustees and managers to track results early and guard against poor performance.

The three types of fund-raising professionals are: (1) the professional fund-raising executive or development officer who is hired as a full-time employee and works for a salary, (2) the professional fund-raising consultant or firm hired and paid a fee and, (3) the professional solicitor or firm who charge a percentage or commission of the funds raised, plus expenses. Fund-raising executives and consultants generally produce higher net income than solicitors.

Cost-Effective Measurements Charities are not the same in how they perform fund raising, nor does a particular form of fund raising perform in the same way for every charity. Program costs and program results vary because of environmental factors, such as: the institution’s popularity and reputation; its history of fund raising; access to donors, volunteer solicitors, and wealth; access to corporations; management expertise and fmancial success; population and geography; and the management skill and experience of the fund-raising professional.

Finding a professional who can assimilate all these variables and combine them into a successful fund-raising program should be the major factor in any hiring decision.

Reasonable Cost Guidelines

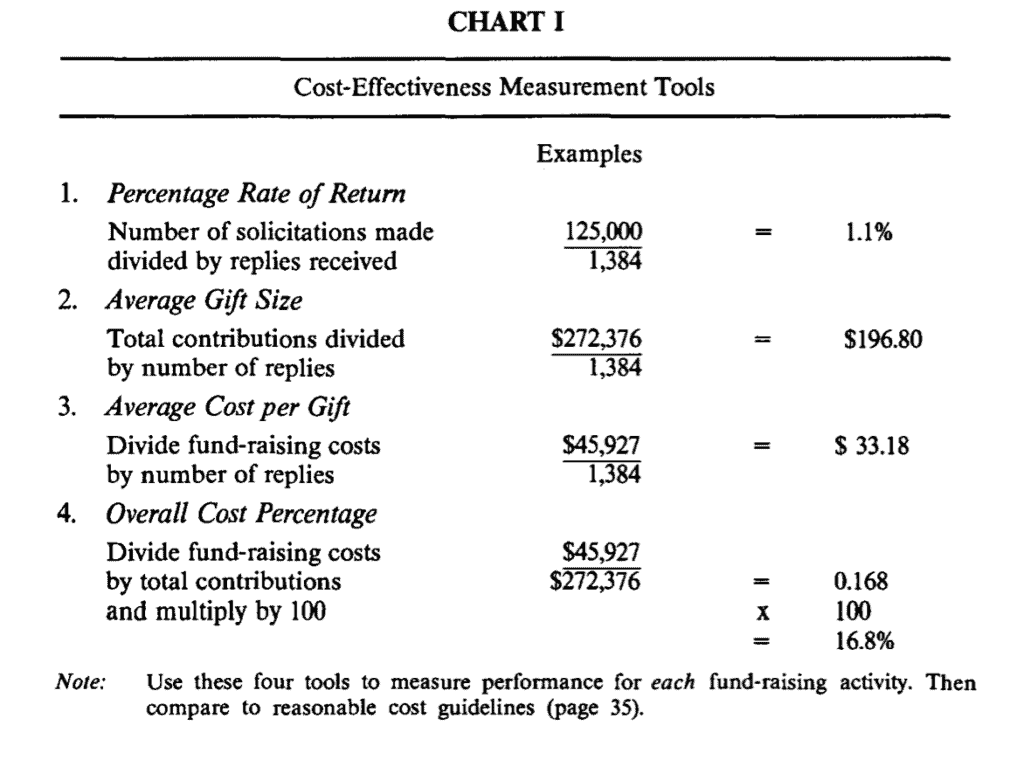

Four measurements are needed to assess the success of fund raising: percentage rate of return, average gift size, average cost per gift, and cost per dollar raised (Appendix, Chart I). Each of these measurements should be applied to each fund-raising method used by the charity in order to monitor progress at regular intervals (monthly or quarterly).

Research on fund-raising costs in the United States is based on the experience of all charities. It suggests that mature programs (those in place for three years or more) should be able to reduce costs to 20 cents per dollar raised, with an impressive net of 80 cents delivered to the charity!l

While “bottom line” figures are valid to measure performance, this figure often represents the results of as many as six separate fund-raising methods in use at the same time. Each method has its own level of reasonable cost, so that true comparisons between institutions are difficult. The fairer comparison is to measure like institutions, method against method, using the following reasonable cost guidelines:

Direct Mail Acquisition/Constituency Building

$1.25 to $1.50 to raise $1.00, plus a 1% rate of return on all lists used in the mailing

Direct Mail Renewal/Constituency Retention

25 cents per $1 raised, plus a 50% rate of renewal among donors of the previous year

Special Events and Benefit Events

50 cents per $1 raised

Corporate and Foundation Solicitation

20 cents per $1 raised

Wills and Estate Planning

25 cents per $1 raised

(plus a lot of patience)

Capital Campaigns

5 to 10 cents per $1 raised

If an organization is using only direct mail for donor acquisition and retention, it should expect average costs above 50 per cent. Adding a capital campaign will cause bottom-line costs to drop significantly because of the new focus on major gifts.

Why do some charities design their annual fund drives as a “campaign”? To be able to recruit volunteers who are willing to solicit a few major gifts. Annual fund drives use direct mail and benefit events, all proven to be less profitable. Thus, some attention to the other methods of raising money is needed to improve overall productivity.

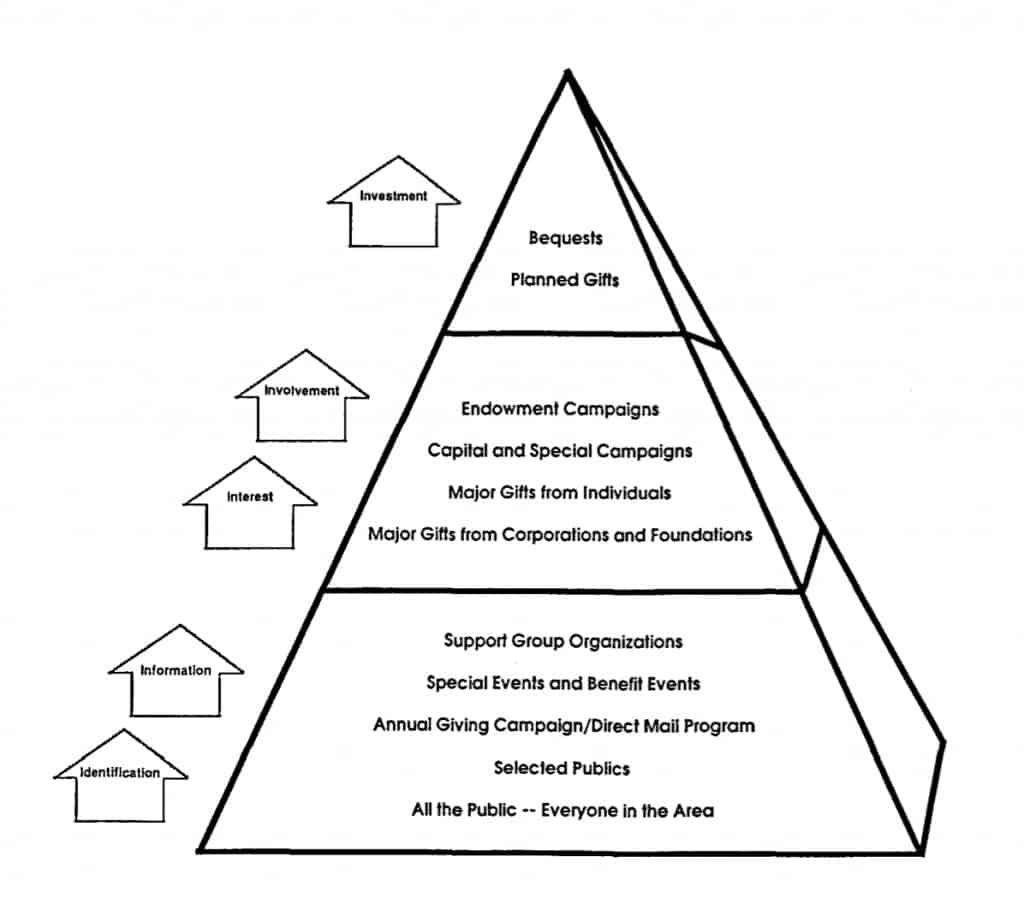

Yet most fund-raising programs must begin, and continue with, basic acquisition and retention, even if they are the least cost-effective methods. Investing in the constant renewal of the donor base is essential. When donor involvement in the institution begins to occur, then donors begin to increase their commitment and can be encouraged to consider more substantial gift opportunities.

This phenomenon is called the “development process” and is illustrated as a pyramid (Appendix Chart II). The aim is to build a strong base, constantly recruiting new donors to add at the bottom so that the potential for progress to the top will be greater.

Progression to the top does not happen by accident. There must be a plan for growth to reach the top of the pyramid. The sin of omission among many fund-raising professionals is lack of a donor relations program, i.e., they fail to realize that after the work to acquire new donors is finished, equal efforts are required to retain them. Such expansion must be well planned and well executed to motivate donors at the lower levels to increase their participation since the future needs of the organization will most often be met by those who are already giving.

The annual campaign is essential to acquire and retain donors but the payoff comes when it becomes the basis for other fund-raising methods. For example, estate planning must have a pool of faithful donors aged 55 years and up for best results; first-time donors are not likely to leave a portion of their estates to a new charity. Capital campaigns and estate planning usually do not succeed as first fund-raising methods since they are dependent upon a reservoir of established donors.

The special pressure on new and smaller charities, along with those just beginning formal development programs, is the unrealistic desire for instant results. Yet major gifts seldom just happen. A minimum three-year investment in building a pool of interested and committed supporters must occur so that traditional, proven, acquisition and retention methods can become effective and offer a sound base from which to seek major gifts.

An understanding of the cost-effectiveness of each fund-raising technique helps to resolve annual budget decisions a bout which programs to support, when new methods should be added, and reasonable estimates of net results. Sound financial forecasts are only possible when they can be based on the experience of previous years (reality).

Types of Fund-Raising Professionals

Professional full-time employees: The largest pool of fundraising talent

consists of professional full-time employees who work for a salary. Most professional fund raisers begin at this level, learning their craft on the job with supervision from more experienced staff. In general, such a development officer is expected to design and supervise all fund-raising methods as well as gift processing and acknowledgement, mail lists, donor relations, recognition programs, and any other organizational activities directly related to fund raising.

Salary ranges in the United States vary by level of assignment, type of institution, number of employees supervised, and years of experience as well as by geography, gender, age and education.2 No doubt the same is true for Canada.

Professional fund-raising consultants: Whether they are independent practitioners or members of a professional fund-raising firm, consultants should have years of institutional experience behind them and a proven track record. They work as advisers, training and supervising staff and volunteers who conduct the actual fund-raising solicitation.

Professional consultants are paid a fee negotiated in advance that is based on the time that will be spent on the project. A written contract provides details of the services that will be provided and payment arrangements.

Consultant fee schedules can be set by the hour, day, week or month, depending on the time spent on the project. For example, a resident full-time campaign director might be included in a monthly fee for total services from a firm at $7,500 per month, whereas retaining the senior professional for a day could cost $1,000.

Professional solicitors: May also be independent practitioners or members of a firm, but do not usually have previous experience as employees in registered charities. Their experience is more often in for-profit and commercial assignments such as direct mail and telemarketing sales.

Professional solicitors prefer to act independently of both staff andvolunteers. They collect and bank the funds raised, pay all expenses and provide the charity with net results or a predetermined amount. Given these arrangements, charities should take steps to ensure receipt of their fair share of the proceeds. A contract is required setting out in detail the solicitor’s services, fees, and expenses.

The Hiring Process

Hiring a development officer: Development officers should be treated like

all other senior employees of the organization. They should have a salary range for their position (entry, midpoint and maximum) and receive annual performance evaluations, salary increases and bonuses in the same manner as other employees. Hiring a senior development officer may require assistance from a professional search firm. Such firms charge a percentage (20 to 30 per cent) of the first year’s salary as their fee, or work for a fixed fee set in advance.

Whether the development officer is recruited through the personnel office or with outside help, volunteers involved with fund raising should participate in hiring interviews along with the senior executive staff. The decision to hire includes reference checks with previous employers and volunteer leaders. Negotiations for salary and benefits should be conducted according to existing institutional policy. Performance reviews and salary adjustments should be based on overall progress toward defined program objectives (not just total cash received) as well as success at reasonable costs.

Hiring a consultant: Fund-raising consultants can perform many duties, from the design of a new program to an audit of existing ones. Many specialize in one or more areas such as direct mail, capital campaigns, or estate planning while larger firms offer the full range of fund-raising expertise. They also hire, train, and supervise their own staff.

Consultants work with institutional staff and volunteers. They train those who will participate in fund raising, prepare the materials and, in general, direct the entire effort from the start to finish. Most importantly, they seldom engage in direct solicitation themselves and do not handle money. All funds received are clearly designated as gifts to the charity and are delivered directly to it Selecting a consultant should include inviting several to submit proposals. These proposals should include an estimate of program requirements, dollars to be raised, time, staff and budget required, and expected fees. Both senior representatives of the fund-raising firm and the staff they will assign to the project should be interviewed by management and volunteer leaders. References should be checked to verify performance and results and the level of satisfaction in previous assignments.

Most consultants will advocate the use of the six traditional methods of fund raising and will assist the charity in its successful implementation of direct mail, benefit events, capital campaigns and estate-planning programs. All records and files are the responsibility and property of the charity.

A detailed contract for services should include staff to be assigned and a schedule for progress reports and expense approvals. I recommend adding a 30-day escape clause should either party believe it necessary to terminate the contract at any point. Fees are based on the amount of time the firm and its staff are on the project plus routine expenses such as travel, meals, and accommodations. Such fees are not based on dollars raised nor a percentage of the goal, but on services rendered.

Hiring a solicitor: Hiring a professional solicitor of funds should include the same steps as those listed above for hiring a professional consultant. One major difference is that solicitors sometimes approach charities with an offer to raise an amount of money for the charity “in its name”, with the promise that the institution will not have to be involved.

The solicitor usually works for a commission or percentage of the money raised. Thus, in a program that raises $100,000, solicitors might incur direct costs of $60,000 as well as being paid a percentage or commission of 20 per cent, resulting in a net of only $20,000 for the charity.

Professional solicitors do not involve the charity’s staff or volunteers in their work. They conduct all financial transactions including the deposit of money received to bank accounts they control, pay all expenses, including their fees, out of these accounts, and deliver the balance to the charity. Such arrangements can sound quite attractive to newer, smaller charities who have no volunteers and believe they cannot afford development staff or consultants. But pursuing such a “quick buck” may not be the best decision for the future of the charity.

Professional solicitors often employ traditional methods but they also run sweepstakes, charity circuses, “Las Vegas” or “Monte Carlo” nights, and program advertising sales linked to benefit events. Often there are limited records on donors and gift amounts from such projects, no “thank you” letters are sent to donors, and no records or files are delivered to the charity after the project is over. While the charity may receive some money, this choice has not moved its fund-raising program forward at all.

Unfortunately for the honest practitioners among these solicitors, many in this business are “scam” artists who run “boiler room” telephone operations and use high-pressure sales techniques to raise money, with the net return to the charity of less than 25 per cent of all funds raised in its name.3 Firms with such track records are to be avoided.

Special Problems for Smaller Charities Newer and smaller charities are usually desperate for immediate gifts for operating costs. Traditional methods of fund raising that require hiring staff and the careful development of donors and prospects over three years in order to achieve “profitability”, seem out of reach or inappropriate to meet their pressing needs. They may be tempted by offers of quick cash with no work on their part. Beware such offers: more than likely they are highly expensive and minimally profitable or even fraudulent.

Volunteer board members and senior management staff in such charities should not be fooled into thinking there are easy ways to succeed in building a solid base of committed donors; there are none. Every charity that has succeeded with fund raising has done so using the traditional, proven methods. The speed of results is not dependent on hiring staff, outside consultants or paid solicitors, but in how quickly board members and volunteers make the personal commitment to give funds and to solicit funds from others. The true role of staff and consultants is to provide professional help and guidance to volunteers committed to success through their own efforts.

The decision to invest in proven methods of fund raising or, instead, electing to hire others to perform the work for you at higher costs with lower net return, must be based on a careful evaluation of what is best for the organization’s short- and long-term benefits. Consider the budget for development as an investment, an investment with an impressive rate of return after the third year of more than 400 per cent annually!

Telemarketing: Something New?

For years, direct mail has been used successfully to acquire new donors and retain existing supporters. Mail communication brings information about your institution or agency to many people, at the same time educating the public about your mission and demonstrating how your organization helps those in need. While the majority of people do not respond each time with a gift, public awareness about your organization will have been increased.

Telephone sales are a similar form of mass communication. They permit your institution to reach out to many people at the same time (but one at a time) asking for their support. Two-way dialogue is a big improvementover one-way mail messages and thus gets better results. Telemarketing has also become quite popular for commercial purposes, which predominate in the market today. However, while people have the freedom to hang up if they choose, many are disturbed by the telemarketers’ invasion of their homes.

Charities who use the telephone for mass solicitation should think carefully about the people they call. When used for first-time “cold calls” to solicit new donors, it may not be any more cost-effective than direct mail. Better results come from calling previous donors who have failed to respond to mailed renewal appeals. Exceptions appear to be in school and college fund raising where students talk with alumni, and in church groups where retention of active membership status is of more significance.

Some consulting firms specialize in organizing and conducting telephone solicitation. Professional solicitors also use this method, possibly more aggressively than consultants. While both may use paid callers, you should inquire about the method of payment (salary, commission or percentage). Employees in the fund-raising office also can organize volunteers to conduct phone solicitations. The American experience with these options suggests that employee-directed telephone projects are least expensive, while consultants are more expensive but more apt to secure higher average gifts. Paid solicitors appear to generate the highest costs with lowest net returns to the charity.

What Else Is New? Cause-Related Marketing The Statue of Liberty campaign in the early 1980s was the first nation-wide example of cause-related marketing in the United States. The American Express Company offered to contribute a fixed sum to this renovation project each time an American Express cardholder used the card to make a purchase. While successful in raising over $1.7 million for the Statue of Liberty campaign and increasing public awareness about the project, this campaign also increased American Express card sales.

Companies who propose this process, technically known as a “charitable sales promotion”, are corporations who wish to use to their advantage the public’s esteem for charities by associating with them in a joint venture.

While those charities selected may receive new revenue, they lack any relationship with these “customers”, receive no roster of donors nor report of total dollars received, and cannot rely upon the company to continue the program if it ceases to be a profitable corporate marketing tool.

Summary

A charitable organization armed with knowledge about reasonable cost guidelines should be able to hire and supervise a competent fund-raising professional. A good professional should have the ability to orchestrate the six fund-raising methods to perform solicitations that meet the needs of the charity. He or she should also be able to demonstrate the potential for success in each method chosen, based on the potential available from the local environment.

Both institution and fund raiser should evaluate progress by monitoring productivity as well as cost-effectiveness. The choice of fund-raising methods should be designed to increase the donor base while promoting additional donor participation at more generous levels.

It is true that “it costs money to raise money”, but it is equally true that the budget for fund-raising is really an investment, one made in a profit centre capable of performing at a rate of return that exceeds 400 per cent annually after three years.

APPENDIX

CHART I

CHART II

FOOTNOTES

1. James M. Greenfield, “Fund-Raising Costs and Credibility: What the Public Needs to Know”, NSFRE Journal, Autumn, 1988, pp. 46-53. This 2Q-per-cent cost/80-per-cent profit performance has been the annual average for many years for all charities. Some, such as hospitals, average about 12-per-cent costs, while newer charities experience upwards of 50-per-cent costs in their first two to three years of fund raising.

2. “Profile: 1988 NSFRE Membership Career Survey”, NSFRE Journal, Winter,

1988, pp. 20-42. This survey provides valuable information on variations and points out some inequities that are being addressed.

3. The Chronicle of Philanthropy, Vol. I, No. 14, May 2, 1989, p. 25. Annual statistics kept by the Office of the Attorney General in Connecticut suggest the average net return to charities who use professional solicitors is only 20 per cent Such a level of performance by any professional fund-raising firm should raise questions about the wisdom of retaining its services.

BIBliOGRAPHY

American Association of Fund Raising Counsel, Inc. Giving USA: The Annual

Report on Philanthropy for the Year 1988. New York, 1989.

Berendt, Robert J. and Taft, J. Richard. How to Rate Your Development Department.

The Taft Group, Washington, DC, 1984.

Council for Advancement and Support of Education and the National Association of College and University Business Officers. Management Reporting Standards for Educational Ihstitutions: Fund Raising and Related Activities. Washington, DC, 1982.

Department of Justice, Government of the United States of America. Internal

Revenue Service Fonn 990, Schedule A and Instructions. Washington, DC, 1988. Fink, NormanS., and Metzler, Howard D.Ihe Costs and Benefits of Deferred Giving.

Columbia University Press, New York, NY, 1982.

Folpe, Herbert K, CPA “Rational Analysis in Non-Profit Organizations”, The

Philanthropy Monthly, October, 1982.

Greenfield, James M. “Determining Your Fund-Raising Costs”, NSFRE Journal,

Spring, 1984.

Hopkins, Bruce R “Tax Exempt Status Threatened by Fund Raising”, Fund

Raising Management, October, 1983.

Jacobson, Harvey J. “15 Ways to Measure Fund Raising Program Effectiveness”,

Fundraising Management, December, 1982.

Levis, Wilson C., and New, Anne. “The Average Gift Size Factor: A Research Project to Explore the Relevance of Average Gift Sizes in Evaluating the Fund Raising Costs of Charitable Organizations”, The Philanthropy Monthly, July/August, 1981.

Levis, Wilson C., and New, Anne. ”The Average Size and Cost per Gift: New

Evaluation Tools for Grantmakers”, Foundation News, September/October,

1982.

Levis, Wilson C., and New, Anne. “Report on the Average Gift Size Study”, The

Philanthropy Monthly, June, 1982.

Manchester, Jay A, CPA “IRS Form 990: An Analytical Tool for Donors”, The

Philanthropy Monthly, November, 1982.

Murray, Dennis J. The Guaranteed Fund-Raising System: A Systems Approach to Planning and Controlling Fund Raising. American Institute of Management, Poughkeepsie, NY, 1987.

Murray, Dennis J. Evaluation of Fund Raising Programs: A Management AuditApproach. American Institute of Management, Boston, MA. 1983.

National Charities Information Bureau. Grantmakers’ Guide to a New Tool for

Philanthropy- Fonn 990. New York, NY, 1983.

Suhrke, Henry C. “A Proposal on Allocating Fund-Raising Costs”, Editorial, The

Philanthropy Monthly, July/August, 1982.

United Way of America. Accounting & Financial Reponing: A Guide for United Ways and Not-For-Profit Human Service Organizations. Alexandria, VA, December, 1974.

JAMES M. GREENFIELD

Senior Vice-President Development and Community Relations, Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian, Newport Beach, California