The financial squeeze resulting from the chronic underfunding of philanthropic organizations in Canada tends to be transferred not only to their beneficiaries and clients but also to their employees. Recent studies confirm that incomes of those who work in charitable organizations are usually lower than incomes of those who work in comparable employment in government and the private sector.1

At least some relief for employees can be provided if charitable organizations make more concentrated efforts to develop tax-effective compensation programs.

Introduction

The basic idea of tax-effective compensation is simple enough. The Income Tax Act casts the widest possible net in its search for revenue. Taxable income includes not only “salary, wages and other remuneration”2 but also the value of”other benefits of any kind whatever enjoyed … in respect of, in the course of, or by virtue of an office or employment”.3 But there are exceptions: opportunities for organizations to provide something of value to their employees which attracts little or no tax.

The opportunities are limited and strictly defined. This makes it all the more important for charitable organizations to take maximum advantage of what opportunities there are. They are available to even the smallest organization and, applied diligently, they can make a substantial contribution to the financial security of employees.

Broadly speaking, the opportunities fall into three categories:

1. Group insurance plans: to protect employees from the financial risks arising from death, disability, and heavy health care costs. While the probability of these events is relatively low, the financial consequences are catastrophic and a prudent individual will seek protection through insurance. Group insurance purchased by an employer is far less expensive, and often more comprehensive, than individual policies. In addition, money spent by an employer to buy insurance for the benefit of employees attracts, at best, no tax at all for the employees or, at worst, tax on the premiums. Even in the worst case, it is cheaper for employees to pay the tax on premiums paid by an employer than it is to pay the premiums themselves.

2. Income-deferral plans: such as pensions and other retirement benefits. As average life expectancies increase, the retirement years have come to represent approximately 20 per cent of an average lifetime. Despite universal government programs and attractive tax-deferral opportunities for individuals who wish to save for their retirement years, pensioners, and particularly elderly women, still constitute one of the most intractable pockets of poverty in Canada. Retirement programs sponsored by an employer can thus be one of the most important benefits an employer can provide.

3. Other benefits and perquisities: payment of tuition fees for employees and their children, parking, subsidized cafeterias, sabbaticals, etc. Certain of these benefits remain non-taxable, others will be considered part of the employee’s income for tax purposes. Nevertheless, even when such benefits are taxable, the tax paid by employees will be far less than the market price for such services.

This paper provides an overview of the structure of typical plans, outlines the tax implications of such programs, and explains their utility to employees.4

Group Insurance Plans

Group insurance plans sponsored by employers confer the following advantages on employees:

(a) Lower cost because of economies of scale;

(b) Access to certain kinds of insurance, such as dental care, which are sold only on a group basis; and

(c) Employer-paid premiums which, generally speaking, do not create a taxable benefit for employees.

This insurance is provided through a group contract between the employer and an insurance company and participation by all employees is normally required to make sure the group is large enough for a reasonable diversity of risks.

The following classes of group insurance are included in most employer sponsored plans:

A. Life Insurance

The amount of life insurance coverage is determined either as a multiple of an employee’s salary (such as one, two, or three times annual earnings) or as a fixed amount for all employees in a specific classification.

One important advantage of a group life plan is the absence of any requirement for medical examinations, except in cases where an individual’s coverage would exceed a predetermined maximum. Of additional importance for any employees in poor health is their statutory right to replacement coverage if they end their employment. Replacement coverage must be made available without a medical examination, regardless of health.

It is also possible to arrange for additional insurance on an optional basis, with participating employees paying the entire cost. Premiums for optional insurance are usually related to the age of the insured person with automatic increases in rates with advancing age. Reduced rates for non-smokers are also available. However, insurance companies will offer optional life insurance only where there is a substantial number of employees (at least 25) and then only if a majority of eligible employees participate.

An employer can pay premiums on up to $25,000 of life insurance without tax consequences for the employee. Premiums on additional insurance are considered a taxable benefit and added to the employee’s income.5 Even so, the net cost to the employee is far less than that for a similar amount of individual insurance.

Group life insurance, depending on the average age of the group, would typically cost from $3 to $6 per annum, for each $1,000 of coverage. For an employee with $50,000 of employer-paid coverage, the taxable benefit would be from $75 to $150. Even at a high marginal tax rate of 50 percent, the annual cost to the employee would be from $37.50 to $75 per annum. The annual cost of $50,000 of individually purchased term insurance for a 30-year-old would be in the $85-$95 range, with premiums increasing at five-year intervals to $90-$95 at 35,$100-$120 at 40,$150-$160 at 45, up to a maximum of$900 to $1,000 by 65.

In cases where the size of the organization, the age of its employees or the financial resources of the philanthropy make an insurance plan inappropriate, some measure of protection can still be arranged through the use of an employer-paid death benefit. The Act allows an employer to make a lump-sum tax-free payment of up to $10,000 to the surviving spouse of a deceased employee. Any additional amount paid by the employer is taxable income for the recipient.6

B. Accidental Death and Dismemberment Insurance

In certain age groups, an accident is the most likely cause of death. For this reason, many employers will add Accidental Death and Dismemberment Insurance to the benefits plan. This insurance pays a benefit only if death is caused as a direct result of an accident. Lump-sum cash benefits are paid to the insured individual for the loss of limbs, eyesight, speech, or hearing as a result of an accident.?

Policies normally exclude accidents resulting from activities where there is a higher than usual degree of risk: hazardous sports, occupational injuries, suicide, and so on. The insurance is relatively inexpensive-as little as $25-$30 per annum for $50,000 of coverage. There is no taxable benefit to the employee if the employer pays the premiums.8

C. Health Care Insurance

While provincial hospital and medical insurance plans provide basic health care coverage for all Canadians, many items are not insured. In a serious illness, these uninsured expenses could amount to hundreds or even thousands of dollars.Tax-effective compensation for employees can be provided through four different categories of plan:

(a) Provincial Hospital and Medical Insurance

In three Canadian provinces-British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontariodirect premiums are levied on subscribers.9 Any contribution by employers to the cost of these plans is added to the employees’ incomes.10

(b) Supplementary Health Care

These plans normally cover such expenses as: private or semi-private hospital accommodation, prescription drugs, private-duty nursing, fees of paramedical personnel such as physiotherapists, chiropractors, osteopaths, speech therapists, and massage therapists, emergency care in another country if the fees are in excess of the limits in the provincial hospital and medical plan, prosthetic devices and equipment such as wheelchairs, crutches, iron lungs, and hospital-style beds. Employer-paid premiums are not a taxable benefit for employees.11

(c) Dental Care

Coverage offered ranges from routine expenses, such as regular checkups and routine fillings and extractions, to more complete plans covering crowns, bridges, dentures, and orthodontia. Employees are not taxed on employer contributions.

Depending on the scope of the coverage, health care plans can range in cost from $25 to $75 per month per family, perhaps even more if claims are higher than anticipated. While most claims are modest and manageable, individual claims of$10,000 or more are possible and do, in fact, occur regularly. Several such claims in a year will be followed promptly by premium increases.

Employers can help control costs through a variety of techniques designed to share the risk with employees. For example, the plan could impose a “deductible”, requiring that employees pay a nominal amount of claims, for example

$50 per annum, before the plan becomes liable. Or a “co-insurance” clause might be incorporated into the contract, requiring employees to co-insure each claim with the insurance company, e.g., the plan might pay 80 per cent of eligible claims in excess of the deductible, with the employee paying the rest of the cost. These arrangements still protect employees from catastrophic expenses.

Group health care plans are of major importance to employees, not only because of their tax-effectiveness but also because the protection they offer is far wider in scope than the plans available to individuals. Indeed, dental care insurance is unavailable in Canada except through a group plan.

(d) Private Health Service Plans.

If an insurance plan for supplementary health and dental care is inappropriate because of the size of the group or the financial situation of the organization, a “private health services plan” is an alternative. By establishing a private health services plan, an employer can pay the medical and dental bills of employees without creating a taxable benefit for them.12 The rules require a formal plan and an employer-employee agreement which binds the employer to pay defined expenses on behalf of the employee and any eligible dependents. In a small organization of three or four employees this is often the only practical way of providing health care benefits since the group might be too small to be considered a safe risk by insurers.

D. Disability Insurance

Few employees are aware that the risk of a long-term disability is greater than the risk of death during the working years. Protection against the financial consequences of a disability is normally provided through two different kinds of plan:

(a) Short-Term Disability Insurance

This insurance provides a continuing income for an initial period, normally not more than six months. The employer might choose to keep the disabled person on the payroll, at full salary or a percentage of full salary, for the specified “waiting period”. Some employers rely only on Unemployment Insurance Sickness Benefits, which will pay benefits for up to 15 weeks of the absence during sickness if the employees have contributed for 20 of the previous 52 weeks. Others, with a sizeable work force, sometimes purchase ShortTerm Disability Insurance from an insurance company.

In some provinces, participation in Workers’ Compensation may be permitted.This would be a useful adjunct to a short-term disability plan if there was a significant risk of an accident, such as a traffic accident, which could occur in the course of an employee’s work.

If the plan provides for continuation of all or part of salary, the employee remains on the payroll with no change in tax status or payroll deductions. If benefits are paid by an insured plan, the income would be tax free if the employee paid the premiums. Alternatively, the employee could also receive the benefits free of tax if the premiums were paid by the employer and the amount of the premiums was added to the employee’s income as a taxable benefit. If any part of the cost is paid by the employer, any benefits received by the employee are taxable.U

(b) Long-Term Disability Insurance

This insurance provides benefi_ts for a disability which continues after shortterm disability benefits have ended. Such a disability may well continue for several years or even longer. Under these circumstances, a new kind of arrangement is called for, one which takes into consideration the possibility of othersources of income, the elimination of employment-related expenses and reduction or elimination of many payroll deductions.

Long-Term Disability Insurance is intended to provide a continuing income, for as long as the disability continues, up to the age of 65 if necessary. Benefits are defined as a percentage of salary, usually ranging from a low of 50 per cent to a high of 70 per cent, subject to a maximum dollar amount.

A group disability plan is typically the “second payer”, i.e., it will make up the shortfall if other sources of income are less than the benefit rate specified by the disability insurance contract. Benefits might be received from Workers’ Compensation, if the disability is occupational in origin, or from Canada Pension Plan/Quebec Pension Plan, if the disability is both total and permanent. In some cases, the amount of benefit from these sources might be more than the benefit provided by Long-Term Disability Insurance, in which case no payment from the insurance plan would be made.

Without some form of insurance, the financial consequences of prolonged disability can be catastrophic and, while individual disability policies are available, they have many shortcomings. For example, individual disability policies are expensive and for those in some occupations, only limited coverage is available. Employees in some occupations are considered uninsurable: one major underwriter in this field will not insure individuals earning under $20,000 and its list of uninsurable occupations includes social service workers along with stevedores, prison guards, and miners.

Costs of a group long-term disability plan depend on a variety of factors: the benefit level, the period between the onset of disability and the commencement of benefits, and the age and occupational mix of the group. Typically, annual premiums might range from $12 to $30 for each $100 of monthly benefit. Similar factors are used to calculate premiums for individual policies. Costs of a typical individual policy, for a 30-year-old office worker, could range from $30 to $50 for the same coverage.

The benefits, if received, are subject to the same tax rules as those applying to short-term disability plans: benefits are free of tax if employees pay the premiums or if employer-paid premiums are reported as taxable benefits received by the employees; benefits are taxable if the employer pays the premiums.

For very small groups, or in situations where the organization cannot obtain as much coverage as it would like, insurance against the risk of permanent and total disability is available. In these plans, the benefit would normally be paid in a single payment, or in periodic payments spread over a two- or threeyear period.

Income-Deferral Plans

Canada has a three-tiered system of retirement security:

1. Government-Sponsored Plans: including the Canada Pension Plan and

Quebec Pension Plan, Old Age Security, Guaranteed Income Supplement, additional tax exemptions for pensioners and taxpayers 65 years of age and over, additional services provided by provincial hospital and medical insurance, elimination of hospital and medical insurance premiums in two of the provinces (Ontario and Alberta) which charge a direct premium, a variety of provincial tax credits, and certain special services provided by some municipalities.

2. Personal Plans: including Registered Retirement Savings Plans and the accumulation of income-producing assets.

3. Employer-Sponsored Plans: including pension plans, retiring allowances, and the continuation of life insurance and health care insurance after retirement.

A. Government-Sponsored Plans

Government-sponsored plans by themselves provide little more than subsistence income. For someone retiring in 1986, the maximum benefit paid by Canada Pension Plan/Quebec Pension Plan is $5,032 per annum, with an additional $3,492 from Old Age Security. A Guaranteed Income Supplement is available to provide additional income in cases where CPP/QPP and OAS are the only sources of income. Despite the universality of these plans, elderly Canadians—and particularly elderly women who have not worked outside the home or who have had sporadic or low-paying employment-constitute one of the most persistent pockets of poverty in Canada.

B. Personal Plans

It seems reasonable to assume that employees of charitable organizations, subject to systemic constraints on their incomes during their careers, will find it difficult to accumulate adequate retirement funds through a personal Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) and personal savings.

C. Employer-Sponsored Plans

In view of the probable inadequacies of both their government and their personal plans, employer-sponsored retirement programs are thus particularly important for employees of charitable organizations. Four different kinds of plan merit study: pension plans, retiring allowances, Group RRSPs, and salary-deferral arrangements.

1. Pension Plans

Traditionally, an employer-sponsored pension plan has been the most usual way of providing a retirement income for an employee. The variations in plan design are virtually limitless, making it possible to design a plan to meet the needs of a specific group of employees within the financial limitations of a specific employer.

There are two broad categories of pension plan:

(a) The “defined benefit” plan: where the benefit is determined by a formula, usually calculated in relation to an employee’s length of service and earnings and a rate of benefit. A typical plan, for example, might base the pension on average income in the final five years of employment, with a benefit rate of 1.75 per cent of that figure. For an employee with 15.5 years of service, and “final average earnings” of$25,000, the pension would be 1.75 per cent x 25,000 x 15.5 or $6,781 per annum, payable at “normal” retirement date.

Such a plan might require contributions by the employee. If so, the employee’s contributions are deductible from income for tax purposes. A defined benefit plan imposes no fixed contribution rate on the employer whose responsibility is only to contribute enough money to guarantee the solvency of the plan. In a year of high investment earnings by the pension fund, for example, little or no contribution by the employer might be required. However, a year of poor investment performance might create a deficiency in the pension fund which must be made up by the employer over a period of time.

In short, a “defined benefit” plan transfers both the investment rewards and the investment risk to the employer. The employer’s ultimate liability is theoretically unlimited. The employee is insulated from both the risk and the rewards of the pension fund investments and receives, at retirement, a pension with a predictable relationship to his or her standard of living.

(b) The “defined contribution” plan: where the employer and the employee each contribute a fixed percentage of the employee’s earnings. These contributions, and the income earned by investing them, are credited to the employee’s account. At retirement, the account balance will be used to buy an annuity providing a lifetime income.14

In a defined-contribution plan, the employer’s cost is limited to the actual rate of contributions. The employee bears the entire investment risk, and reaps the entire investment rewards, if any. Because the investment income accrues to the benefit of the employee, defined-contribution plans can often be more expensive on a long-term basis than defined-benefit plans.

In the past, employees’ perceptions of pension plans have been adversely affected by their complexity. Because employees do not, as a general rule, understand their plans, there have been widespread criticisms of pension plans in general in recent years, leading to vociferous demands for changes in pension legislation. Major changes in plan design are now taking place across the country. These changes will be of primary benefit to people who change jobs frequently, and to spouses of pensioners.

Historically, pension plans have been considered to be practical only for major employers. This is no longer true.It is now possible to implement pension plans for small organizations with only minimal administrative costs and complexities. Moreover, employers considering a pension plan to facilitate the orderly accumulation of funds over a long period to provide for the security of retiring employees should bear in mind that much of the ultimate cost will be derived from the investment earnings of the fund.

2. Retiring Allowances

In some instances a “retiring allowance”is a useful way of providing for retiring employees. A retiring allowance is defined as money received by an employee “on or after retirement … from an office or employment in recognition of … long service.”15 Within limits, a retiring employee can defer tax on this money by transferring it to a personal Registered Retirement Savings Plan which, in tum, can be used to provide a lifetime income. The maximum amount eligible for transfer is $2,000 for each calendar year of employment and an additional $1,500 for each calendar year for which the employee receives no pension credits.16

For an organization with no pension plan, or in situations where a retiring employee will receive an inadequate pension because of short service, the retiring allowance can be a useful device. It has the disadvantage, however, of requiring that substantial sums must be found at a particular time. The financial situation of a charitable organization may not always permit this.

3. Group RRSPs

An alternative to the pension plan is a Group Registered Retirement

Savings Plan. Although, technically speaking, there is no such thing as a “Group” RRSP-each RRSP is an individual contract between the planholder (or “annuitant”) and the financial institution issuing the plan-once an individual has opened an RRSP, the employer can make direct contributions to it.

Normally, a Group RRSP will require a basic contribution by the employee, with a matching contribution by the employer. This ensures that money in excess of the normal salary schedule is set aside for the employee’s retirement. This money is, of course, the employee’s money and must be reported as part of the employee’s income, with an offsetting deduction for the RRSP contribution.

The Group RRSP has many of the characteristics of a defined-benefit pension plan and is normally easier to administer than a moneypurchase pension plan, making it particularly attractive to organizations with only a few employees.

4. Salary Defe”al

Prior to the February 1986 Federal Budget, the Income Tax Act provided for an “Employee Benefit Plan”, a device that could be used to supplementor replace any of the retirement plans outlined above.It permitted an employer to deposit almost unlimited amounts in an Employee Benefit Plan for individual employees and to shelter the money from tax until the employees withdrew it.

The federal government came to the conclusion last year that Employee Benefit Plans were being misused, particularly in the non-profit sector, so amendments to the Income Tax Act placed before Parliament this year will virtually eliminate the Employee Benefit Plan as a funding vehicle for retirement.

Perquisites

For several years the federal Department ofFinance has been moving steadily towards taxation of some of the time-honored perquisites provided by some employers on a tax-free basis. However, some opportunities still remain to provide tax-effective compensation of this kind.

1. There is no taxable benefit if an employer pays an employee’s tuition fees for work-related courses. However, if the course is taken outside of normal working hours, Revenue Canada assumes it is for the employee’s personal benefit and will assess the amount paid as taxable income.17 In most cases, however, the amount can be claimed as a deduction.If tuition fees are paid for children of an employee, a taxable benefit is conferred on the employee and only the child can claim the tuition fee deduction. Even so, there are obvious financial advantages to an employee from a tuition-fee program for his or her children.

2. If an employee is required to use a personal automobile on work-related travel and receives no reimbursement, the employee may deduct the actual expenses, including gas, oil, maintenance and repairs, insurance, and capital cost allowance. In these cases, it is important to keep an accurate record of mileage to identify the proportion of work-related driving.18

3. Provision of employee amenities, such as parking facilities and subsidized cafeterias does not create a taxable benefit. In the case of cafeterias, however, it is expected that a nominal charge will be made to employees to cover at least the actual cost of food and its preparation.19

A Typical Plan

To illustrate the costs to the employer and the benefits to an employee, consider the following plan as one which might typically be provided by a charitable organization:

Group Life Insurance: coverage equal to twice annual salary;

Accidental Death and Dismemberment Insurance: coverage equal to twice annual salary;

Long-Term Disability Insurance: a benefit level of 65 per cent of pre-disability income;

Supplementary Health Care: coverage for semi-private hospital accommodation, prescription drugs, paramedical services, foreign travel coverage, and vision care;

Dental Care: routine diagnostic and preventive services, major restorative ser

vices, and orthodontia;

Pension Plan: a “defined contribution” pension plan with a contribution rate of four per cent of salary by both the employer and employee.

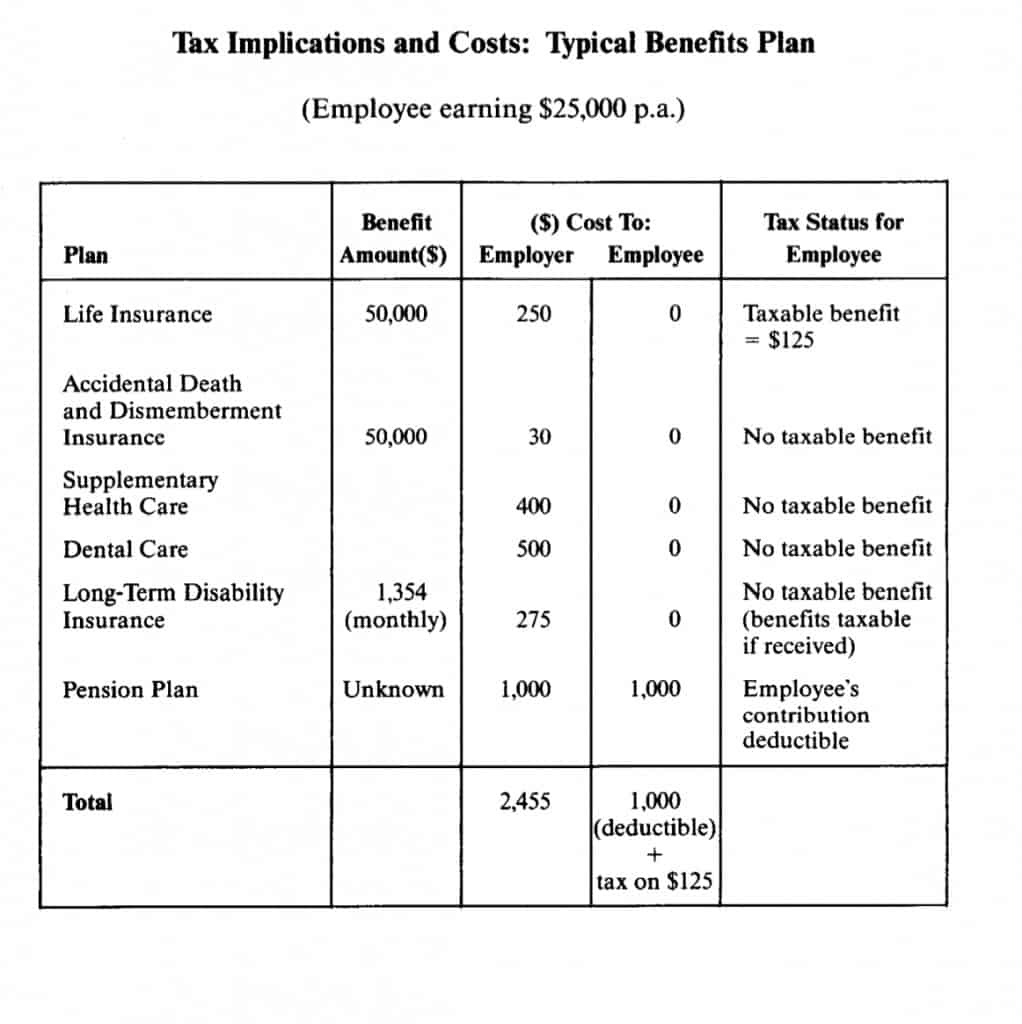

The table below (see image) summarizes the tax implications and typical costs20 for an employee with a dependent family who is earning $25,000 per annum:

In this example, the employer’s annual cost is $2,455, or slightly less than 10 per cent of the employee’s salary. The employee’s cost is $1,000, deductible from income for tax purposes, plus the tax on $125 of taxable benefits. In return, many of the employee’s needs for insurance protection including health care and dental costs for the entire family as well as retirement security are looked after in a more comprehensive and more cost-efficient way than most individuals could achieve by their own efforts.

Conclusion

Employer-paid group insurance, retirement programs, and perquisites will not by themselves eliminate all the difficulties faced by charitable organizations in developing adequate compensation packages for their employees out of their chronically tight budgets, but they offer significant opportunities and advantages to employers and employees alike.

Comprehensive benefit plans can enhance the ability of charitable organizations to attract and retain high-calibre employees in competition with government and the private sector. They can make an important contribution to improved employee relations. They can help charitable organizations to conform to enlightened contemporary employment standards which recognize that certain employee needs can only be met satisfactorily through employersponsored plans.

Equally important, by taking some of their compensation in this indirect and tax-effective form, employees can enhance their personal financial security in the most effective way possible.21

Many charitable organizations are, of course, already providing comprehensive and effective programs for their employees. However, many, particularly among the small organizations, are not. Organizations in this category should not be deterred by fear of the cost. Instead, they should consider whether the cost of the lost opportunity is not more than the short-term saving. A useful program can be developed over a period of years in easy stages, starting with whatever cost can be afforded immediately.

FOOTNOTES

I. See, for example, Wage and Benefits Survey of the Non-Profit Sector. Project Manage, University of Manitoba Continuing Education Division, 1985. (Reported in: Jacke Wolf, “Continuing Education and the Voluntary Sector”, The Philanthropist. Vol. VI, No.2, Summer 1986, p.21.)

2. Income Tax Act, subsection 5(1).

3./bid., paragraph 6(l)(a).

4. Some of the programs described in this paper can also be used to extend coverage to volunteer workers for the philanthropy, thus protecting volunteers from certain hazards which might arise from their volunteer work. A detailed discussion of this aspect of fringe-benefit plans is outside the scope of this paper. (See also, footnote 7, infra.)

5. Income Tax Act, subsection 6(4).

6. /bid,subparagraph 56(l)(a)(iii).

7. In many situations, a charitable organization could insure workers such as volunteer drivers or program workers, against accidental death or injury while they were working as volunteers.

8. Income Tax Act,subparagraph 6(l)(a)(i).

9. In Quebec, a direct payroll tax is levied on both employers and employees. This is not considered to be a premium and the tax paid by an employer does not become a taxable benefit for the employee.

10. Revenue Canada Taxation, Interpretation Bulletin IT-470, February 16, 1981, paragraphs 14, 15, 16.

11. The Federal Budget of 1981 proposed to treat employer-paid premiums for health care and dental plans as a taxable benefit. The proposal was withdrawn after widespread protest.

12. Revenue Canada Taxation Interpretation Bulletin IT-339R, June I, 1983.

13. Income Tax Act, paragraph 6(l)(t). See also Interpretation Bulletins IT-428 and IT-

54.

14. At present, a woman buying an annuity will receive a lower monthly income than a man of the same age for each dollar of purchase price. From an actuarial viewpoint, the annuities are of equal value since, on average, women live longer than men and will probably receive more payments.Critics claim, however, that the present practice is discriminatory, especially since other factors which correlate with life expectancy, such as race, education, and income levels, are ignored in setting annuity rates.Itis likely that the present practice will be eliminated by government action or court decisions within a few years.

15. Income Tax Act, paragraph 248(l)(a).

16./bid, paragraph 60 (j.l).

17. Revenue Canada Taxation,/nterpretation Bulletin IT-470, Feb. 16, 1981, paragraphs

17, 18, 19.

18. Ibid, paragraph 19.

19./bid, paragraph 27.

20. Costs shown are illustrative and indicate only the approximate premiums an employer might expect to pay for an employee group of”average” age and “average” risks.

21. Important changes in the tax treatment of retirement savings were announced by Finance Minister Michael Wilson on October 8, 1986. If approved by Parliament, the changes will take effect in the 1988 taxation year and will mean a substantial increase in the opportunities for most Canadians to make tax-deductible retirement savings through pension plans and Registered Retirement Savings Plans. The most significant changes are:

1. An increased limit on the amount of tax-deductible contributions to RRSPs and pension plans. For the 1986 taxation year, the limit will be 18 per cent of salary, with a dollarlimit of$11,500. The dollar limit will increase to $15,500 by 1990.

2. However, the limit will be reduced by the amount of employer contributions to a pension plan. It is simple enough to calculate the amount of employer contributions to a defined-contribution plan (see page 31), but it is something else to value employer contributions to a defined-benE1it plan where, by definition, the employer’s responsibility is not to make a pre-determined dollar contribution, but to keep the plan solvent.

To make this apples-and-oranges comparison, Revenue Canada will use a complex set of formulae to determine the value of employer contributions for each of the 8,000-plus defined-benefit plans in Canada and will then notify the 4,250,000 participants individually of their contribution limits each year.

GEORGE V. FORSTER

Vice-President, Reed Stenhouse Associates Limited